Abstract

In this paper, fractional calculus has proven to be invaluable in disease transmission dynamics and the creation of control systems, among other real-world problems. To investigate vaccine and treatment dynamics for disease control, this work focuses on Kawasaki illness and uses a unique fractional operator called the modified Atangana-Baleanu-Caputo derivative. The stability analysis, positivity, boundedness, existence, and uniqueness, are treated for the proposed model with novel fractional operators. Additionally, it investigates the effects of different parameters on the reproductive number. It verifies the existence and uniqueness of the solutions to the suggested model using Banach fixed point and the Leray-Schauder nonlinear alternative theorem. Employs Lyapunov functions to determine the model equilibria analysis global stability. The numerical simulation and results utilized the two-step Lagrange interpolation approach at various fractional order values. The results are contrasted with those obtained using the widely recognized ABC method and comparisons are also made to show the effects of the proposed method for the epidemic system. This model advances beyond existing Kawasaki disease models by incorporating fractional-order dynamics, which capture memory effects and long-range dependencies in biological systems, offering more accurate representations of disease progression. The inclusion of chaos stability control provides novel insights into managing complex, nonlinear behaviors, enhancing both theoretical understanding and potential clinical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infants and young children are susceptible to Kawasaki disease (KD), an inflammatory illness that affects blood vessels throughout their bodies1,2. In pediatric populations across North America, Europe, and Japan, Kawasaki disease is presently regarded as the predominant etiology of acquired heart disease3,4. The prevailing consensus has shifted regarding childhood Kawasaki disease, as it is increasingly acknowledged that the cardiovascular sequelae associated with this condition may extend into adulthood5,6. Although the exact etiology of Kawasaki illness is still unknown, findings from our laboratory7,8 and other laboratories9,10 support the theory that it is most likely caused by a traditional antigen. In11,12, it is reported that pediatric patients administered high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin exhibit a reduced likelihood of developing coronary arteritis and, more specifically, coronary artery aneurysms; in the absence of treatment, as many as 30% of these patients may develop such conditions. In 60–75% of Kawasaki disease patients, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) treatment results in coronary artery aneurysms (CAA) regression13,14. Nevertheless, it is unclear how precisely IVIG lowers the incidence of cardiovascular problems15. Around 15–20% of patients diagnosed with (KD) display suboptimal reactions to (IVIG) treatment, and individuals within this specific category exhibit a heightened likelihood of experiencing coronary artery aneurysms16,17. A diverse array of both congenital and acquired immune cell phenotypes has been correlated with the penetration of the vascular endothelial layer in Kawasaki disease. The presence of an aggregation of monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils within the arterial vessel walls18,19, in conjunction with activated \(CD8^+\) T lymphocytes and \(IgA^+\) plasma cells, is observed in the post-mortem human tissues subjected to immunohistochemical examination20. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-1 beta, are released by immune cells that permeate the host organism. These cytokines promote the growth of CAAs and damage to vascular endothelial cells23,24. In the most badly affected instances, Kawasaki disease is thought to be a medium-sized vasculitis that results in coronary artery aneurysms. Aortic, axillary, brachial, and iliac artery aneurysms can sporadically develop, and there may be systemic vascular involvement. It has not yet been documented if KD has an impact on microcirculation.

The utilization of fractional calculus in addressing practical issues, encompassing healthcare and a multitude of other domains, has attracted considerable interest from scholars worldwide. Atangana and Baleanu developed derivatives that incorporate non-local and non-singular kernels using the generalized Mittag-Leffler function27. The Atangana and Baleanu fractional operator was recently developed inside Caputo’s theoretical framework28. A fractional-order model for managing toxin activity and fires caused by humans is presented in the article29. It integrates simulations and chaos control approaches. It uses a modified ABC operator to optimize the model performance in handling complex environmental dynamics. To better understand the spread and control of the virus,30 investigates the stability and complicated dynamics of a COVID-19 epidemic model utilizing a non-singular Mittag-Leffler law kernel. The fractional-order epidemic models in life sciences, discussing their historical development, current applications, and future potential for more accurately modeling the spread and control of infectious diseases31. The dynamics and stability of a COVID-19 pandemic model under a harmonic mean type incidence rate are examined in32 by fractional calculus analysis. The HBV epidemic model33 uses a convex incidence rate and sensitivity analysis to determine the main factors affecting the virus’s propagation. A fractional COVID-19 pandemic model34 using real data from Pakistan and incorporates the ABC operator for improved modeling accuracy. It investigates the dynamics and potential interventions for controlling the spread. The Caputo-Fabrizio definition is used in study35 to examine a fractional-order boost converter with inductive loads. It explores the system’s behavior, stability, and performance under fractional-order dynamics. A fractional-order Zener model36 for viscoelastic dampers, incorporating temperature-order equivalence to better capture the damping behavior. It focuses on improving the accuracy of modeling viscoelastic materials in engineering applications. Study37 presents a fractional-order mathematical model for the COVID-19 outbreak, accounting for both symptomatic and asymptomatic transmissions. It analyzes the dynamics of the disease spread with fractional derivatives for more accurate predictions and control strategies. A fractal-fractional mathematical model to regulate the prevalence of tuberculosis38, emphasizing stability conditions, simulations, and sensitivity analysis to evaluate the model performance in practical settings. The article39 explores new bifurcation results for fractional-order octonion-valued neural networks that incorporate delays, examining how these delays affect the network dynamics and stability. In40 author investigates bifurcation phenomena in fractional neural networks with multiple delays and proposes a control scheme to manage the complex dynamics and enhance network stability. The study41 demonstrates the existence of chaotic behavior and stability regions in a piecewise modified ABC fractional-order leukemia model, validated through symmetric numerical simulations. The existence and uniqueness of solutions in a modified-ABC fractional-order smoking model42, highlighting its applicability to real-world scenarios. The use of artificial intelligence in data analysis with error recognition to improve liver transplantation outcomes in HIV-AIDS patients43, utilizing modified ABC fractional-order operators for enhanced precision. The research44 proves the existence of solutions and introduces a numerical scheme for a generalized hybrid class of n-coupled modified ABC-fractional differential equations, demonstrating its effectiveness through a practical application.

The modified Atangana-Baleanu-Caputo derivative is significant for the Kawasaki disease model because it introduces a non-local, memory-dependent mechanism that better captures the disease persistence and relapse characteristics. This fractional approach allows the model to reflect the influence of past infection and immunity states on current disease dynamics, providing a more accurate depiction of Kawasaki disease progression and treatment response. The integration of fractional order derivatives into disease modeling represents a significant advancement in epidemiological research. By capturing complex dynamics through memory effects and non-local interactions, these models offer improved insights into disease behavior and control strategies. As demonstrated across various studies, including those on COVID-1945 and hepatitis B46, fractional calculus not only enhances model accuracy but also informs public health interventions effectively.

This study introduces a fractional-order Kawasaki disease model using the modified Atangana-Baleanu-Caputo derivative, which better captures the disease’s persistent and recurrent nature compared to classical models. Analysis reveals that lower fractional orders correlate with more aggressive disease progression, while higher orders show a dampening effect on inflammation. The MABC model demonstrates superior accuracy in simulating Kawasaki disease dynamics compared to the standard ABC model. The findings suggest that manipulating fractional orders could offer potential control points for disease interventions. The previous study23 utilized a classical integer-order model to investigate key interactions in the pathogenesis of Kawasaki disease. In contrast, this study presents a new fractional-order model of Kawasaki disease, employing the modified Atangana-Baleanu-Caputo (MABC) derivative. This approach effectively captures memory effects and complex immune interactions, thereby improving the accuracy of simulations related to the inflammatory processes. Additionally, the study explores chaos control and stability by using Lyapunov functions and fixed-point theorems to analyze equilibria and the uniqueness of solutions.

Section 1 of this article serves as an introduction, and Sect. 2 provides a general definition of the strategies that are offered. The suggested models that are positively invariant, with equilibrium points, reproductive potential, and sensitivity examined, are shown in Sect. 3. Part 4 evaluates the proposed model stability while accounting for Lyapunov stability. The discrete Kawasaki disease model chaos is examined in Sect. 5. In Sect. 6, fixed point theory is used to verify the existence and uniqueness of a system of solutions. In Sect. 7, the Atangana Baleanu in Caputo sense fractional order system is solved using a unique numerical method. Graphs representing the numerical results of the proposed model are presented in Sect. 8. The conclusion is given in the last section, number 9.

Basic concepts

In this section, we will look over some basic ideas.

Definition 2.1

28Let \(w \in {M}\left( {\left[ {0,\mathscr {Q}} \right] } \right)\) and \(\eta \in (0,1)\),\(\mathscr {Q} > 0\). The ABC fractional derivative of a function w(t) defines it as

Definition 2.2

28The ABC fractional integral connected to the function w(t) is conceptualized as follows:

where \(\eta \in (0,1)\) and

Definition 2.3

28The MABC derivative for \(w \in {L}(0,\mathscr {Q})\) and \(\eta \in (0, 1)\) can be formulated as follows: Consider a function \(x \in {L}(0,\mathscr {Q})\). For \(0< \eta < 1\), the MABC derivative is defined as

where \({q _\eta } = \frac{\eta }{{1 - \eta }}\) and \({A} {B}(\eta ) = 1 - \eta + \frac{\eta }{{\Gamma (\eta )}}.\)

The Laplace transform

Definition 2.4

28\(w \in {L}(0,\mathscr {Q})\) and \(\eta \in (0, 1)\) MABC integral is

Definition 2.5

28For \(w'(t) \in (0,\infty )\) and \(\eta \in (0, 1)\) we have

where \(\eta \in (0,1)\) and \({\mathscr {W}(\eta )}\) satisfies a normalizing function \(\mathscr {W}(1) = \mathscr {W}(0) = 1.\)

Lemma 1: Let \(\mathfrak {Q}\in \mathbb {R}^{+}\) be a differentiable function. Then,

Mathematical model

The Kawasaki disease model has been notably shaped by previous research23. A four-category classification system is explained by means of the modeling equations regarding the ways in which different concentrations impact endothelial cell function and the inflammatory response. These equations include elements including cellular proliferation, activation by vascular endothelial growth factors, depletion owing to inflammatory stimuli, and intrinsic apoptosis to adequately depict the dynamics of normal endothelial cell concentration (E). Furthermore, they yield insights into the dynamics of vascular endothelial growth factor (V), chemokines, and activated adhesion factors (C). Ultimately, the model evaluates the dynamics of inflammatory factor concentrations (P), which are regulated by adhesion factors and the activation of immune cells represents in Figure 1. Biological parameters and their meanings are display in Table 1.

The fractional-order model is chosen for its ability to incorporate memory effects and long-range dependencies inherent in biological systems, which integer-order models cannot capture.

under the initial conditions

Positively invariant

Lemma 2: The region \({\gamma _l}{ \in \mathbb {R}^4_+}\)

the system delineated in (8) in every solution, and the specified system within \(\mathbb {R}^4_+\) exhibits positive invariance under the stipulation of non-negative.

Proof

The following are the results from the (8) that we shall present:

According to the system (10), the vector field is said to be localized in the region \(\mathbb {R}^4_+\) on each hyperplane covering the non-negative orthant with \(t{ \ge 0}\). \(\square\)

As \(E(t)+V(t)+C(t)+P(t)=N,\). Each subpopulation is located in [0, N], where the overall population N is assumed to be constant. Because of this, the subpopulation \(E(t)+V(t)+C(t)+P(t)\) are also bounded.

Equilibrium points and \({R}_{0}\)

The Kawasaki disease model disease-free points are \({E^0} =(\frac{r}{{{d_1}}},0,0,0),\) and the Kawasaki disease model endemic equilibrium point is

where

In the modified fractional-order Kawasaki disease model, the reproduction number is crucial for assessing the potential spread of the disease within a population.

Let

In particular, \(F V^{1}\) represents the spectral radius of the next generation matrix, which is the reproductive number.

It is widely recognized that when \({R_0}< 1\), the transmission of the infection will ultimately cease. Conversely, the disease will propagate throughout the population if \(R_0 > 1\). Figure 2 shows the impact of several parameters on \(R_0\).

Sensitivity snalysis

Sensitivity analysis demonstrates that fractional-order parameters significantly influence system stability, offering deeper insights into disease progression. These advantages highlight the fractional-order model’s superior capability in modeling Kawasaki disease dynamics. The sensitivity of \({R_0}\) is following.

Positive sensitivity indices are associated with an elevation of \(R_0\), whereas negative indices are correlated with a reduction in this value. The sensitivity index is linked to the \(R_0\) parameter. Figure 3 elucidates critical elements that affect transmission potential, thereby facilitating the discernment of essential variables and their implications on the propagation of Kawasaki disease. Parameters like r, \(k_2\), \(k_3\), \(k_4\), and \(k_5\) in Figure 3 have a positive sensitivity index and positively affect \(R_0\). Increasing r, \(k_2\), \(k_3\), \(k_4\), and \(k_5\) can either increase the value of \(R_0\) or cause an outbreak. However, parameters with a negative sensitivity index, such as \(d_1\), \(d_2\), \(d_3\), and \(d_4\), have a negative impact on reducing the disease’s progress.

Stability analysis

To enhance comprehension of the dynamic features of the suggested model system (8) and the ways in which control strategies impact the dynamics of infectious disease transmission, a qualitative analysis of the system is conducted. The infectious model stability features are examined first.

Local stability

Theorem 4.1

An equilibrium free \({E^0}\) of the Kawasaki disease exhibits asymptotic local stability when \({R_0} < 1\). Unstability exists if \({R_0} > 1\).

Proof

For the system (8) at \({E_0}\), the Jacobian can be expressed as

Verifying that each and every eigenvalue of the matrix \(J(E^0)\) satisfies the stability condition is both necessary and sufficient for the equilibrium point \(E^0\) to be locally asymptotically stable:

Jacobian matrix has the following eigenvalues: \({\lambda _1} = -0.5\), \({\lambda _2} = -0.1305\), \({\lambda _3} = -1.4347\), \({\lambda _4} = -1.4347\). It is obvious that the point \(E^0\) is locally asympotically stable if \({R_0} < 1\)and all the eigenvalues of \(J(E^0)\) are negative. \(\square\)

Global stability

Lyapunov first derivative

For the endemic Lyapunov function, \(\{ E,V,P,C\},\) \({_0^{MABC}D_t^\eta L}\) < 0, is the endemic equilibrium \({E_* }\).

Theorem 4.2

The endemic equilibrium points \({E_ * },\) in the Kawasaki disease model are globally asymptotically stable when \(R_0\) > 1.

Proof

The Lyapunov function is expressed as follows:

Using Lemma 1 and taking modified ABC derivative, we get

Using system (8) we get,

Putting \(E = E - {E^ * }\), \(V = V - {V^ * }\), \(C = C - {C^ * }\) and \(P = P - {P^ * }\) leads to.

Now, we write

It is achieved that if \(\theta < \phi\), this yields \(_0^{MABC}D_t^\eta L < 0\), however when \(E = {E^*},V = {V^*},C = {C^*} and P = {P^*}.\)

It is possible to demonstrate the proposed model largest compact invariant set.

By employing the Lasalles invariance principle if the system is stable then \({E^*}\) is also stable within it. \(\square\)

Remark 1

Fractional-order derivatives in Lyapunov functions affect stability criteria by introducing a memory-dependent behavior, reflecting past states in the stability analysis, unlike standard integer-order systems. This added memory component allows for slower convergence rates, which captures the persistent and recurrent nature of Kawasaki disease dynamics more accurately.

Existence criteria

Lemma 5.1

The initial equation of the MABC-FDE framework, denoted as equation (8), encompasses solutions of a nature that is elucidated in the subsequent discussion.

where

Simlerly, for others, where

A solution for the modified ABC model is determined based on the following assumptions:

\(\mathscr {W}^\star\) Consider \(E,\bar{E}, V,\bar{V}, C, \bar{C}, P, \bar{P} \in \mathbb {L}\left[ {0,1} \right] ,\) is a continuous function with the higher limit, show that \(\left\| E \right\| \le {\daleth _1},\,\,\left\| V \right\| \le {\daleth _2},\,\left\| C \right\| \le {\daleth _3},\,\left\| P \right\| \le {\daleth _4},\) where \(\daleth _1, \daleth _2, \daleth _3,\daleth _4\) are made up only of positive constants. To elucidate further, let us suppose that: \({\beth _1} = \left( {\frac{{{k_6}\daleth _2}}{{1 + \daleth _2}} - {k_1}\daleth _4 - {d_1}} \right) ,\) \({\daleth _2} = - {d_2}\), \({\daleth _3} = - {d_3}\) and \({\daleth _4} = - {d_4}\).

Theorem 5.2

The \({\gimel }_j\) indexed by j within the domain \(N_{1}^{4}\) will adhere to the Lipschitz condition contingent upon the veracity of the assumption \(\mathscr {W}^\star\), provided that all \({\beth _j}\) are less than 1 for each j in the specified set.

Proof

We start by proving that the function \({{\gimel }_1}(t, E)\) satisfies the Lipschitz condition. The implication of \(\mathscr {W}^\star\), which we have, is used to achieve this.

\({\gimel _1} = \left( {\frac{{{k_6}{\daleth _2}}}{{1 + {\daleth _2}}} + {k_1}{\daleth _4} + {d_1}} \right) .\)

\(\beth _2 = d_2\).

\(\beth _3 = d_3\).

\(\beth _4 = d_4\). It can be discerned that the Lipschitz condition is fulfilled by the elements \({\gimel }_1,{\gimel }_2,{\gimel }_3,{\gimel }_4\). Furthermore, it can be conclusively shown that each of the \({{\gimel }_j}\) for \(j=1,2,3,4\) adheres to the Lipschitz condition, thereby corroborating their legitimacy, as derived from equations (19) to (22).

Suppose there is a

The next stage is to define the recursive formulae for the model, which is listed as follows:

In a same pattern we solve for V,C,P. \(\square\)

Theorem 5.3

Should the veracity of the forthcoming assertion be substantiated, then the MABC Kawasaki disease (8) presents a solution predicated on the premise that \({\mathscr {W}^\star }\) must be affirmed as accurate.

Proof We define function as follows:

where \(\daleth < 1\) and \(n \rightarrow \infty ,\) \({E_n} \rightarrow E\) similarly we have

Due to the fact that \(\mathscr {E}{j_n}(t) \rightarrow 0\) as \(n \rightarrow \infty\) for \(j \in N_1^4\) and \(\daleth < 1\), Hence prove is done.

Theorem 5.4

If the following statement is true, then the unique solution given by the MABC model (8) is:

Proof

We may look at \(\bar{E}(t)\), \(\bar{V}(t)\), \(\bar{C}(t)\), and \(\bar{P}(t)\) as potential alternatives. Following that, we have:

\(\square\)

Likewise, for additional compartments

and so

when \(\left\| E - \bar{{E}} \right\| = 0,\) the inequality (46) is true, E must equal \(\bar{{E}}.\) In a comparable direction, we have

Therefore, the solution produced by the Kawasaki disease exhibits the property of uniqueness.

Chaos control

In this section, we use the linear feedback control method to stabilize system (8) to its equilibrium positions. The fractional-order system in its controlled form (8) will be examined as follows:

where \(w_1,w_2,w_3,w_4\) are control variables, and the system equilibrium point is \(E^0\) (8). For the system (35), the Jacobian matrix at \(E^0\) is derived as

The characteristic equation of the Jacobian matrix \(J(E^0)\) is given by

characteristic polynomial of for the equilibrium point \(E^0\) is given as

where

Based on linear stability theory the local dynamics of controlled discrete Kawasaki disease model (35) about \({E^0}_{\left( {\frac{r}{{{d_1}}},0,0,0} \right) },\) can be stated as following Lemma:

Lemma 6.1

\({E^0}_{\left( {\frac{r}{{{d_1}}},0,0,0} \right) },\) of controlled discrete Kawasaki disease model (35) is a sink if

where \(K_1^*,K_2^*,K_3^*\) and \(K_4^*\) are depicted in Eq (37).

Proof

Since \(J{({E^0})_{\left( {\frac{r}{{{d_1}}},0,0,0} \right) }}\) about interior equilibrium solution \({E^0}_{\left( {\frac{r}{{{d_1}}},0,0,0} \right) }\) of controlled discrete Kawasaki disease model (35) has characteristics polynomial which is depicted in model (36).\({E^0}_{\left( {\frac{r}{{{d_1}}},0,0,0} \right) }\) of controlled discrete Kawasaki disease model (35) is a sink if \(\left| {K_1^* + K_3^*} \right| < 1 + K_4^* + K_2^*,\,\)

\(\left| {K_1^* - K_3^*} \right| < 2\left( {1 - K_4^*} \right) ,\) and \(K_4^* + K_2^* + K_4^{{*^2}} + K_1^{{*^2}} + K_4^{{*^2}}K_2^* + K_4^*K_3^{{*^2}} < 1 + 2K_4^*K_2^* + K_1^*K_3^* + K_4^*K_1^*K_3^* + K_4^{{*^3}},\) \(K_2^* - 3K_4^* < 3,\) where \(K_1^*,K_2^*,K_3^*\) and \(K_4^*\) are depicted in Eq (37). \(\square\)

Numerical scheme

Following the equation stated in (8), we get:

With the help of44,47, we construct a numerical approach for (39) by applying Lagrange interpolation polynomials. Substituting \(t_{n+1}\) for t yields

By the Lagrange interpolation, we have

By the help of (39) and (41), we have

Solving the integrals, we get

Similarly,

and

Results of proposed scheme

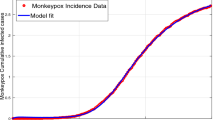

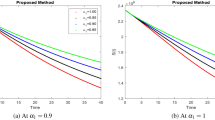

The temporal dynamic characteristics pertinent to the fractional-order epidemiological model for Kawasaki disease (8) are examined through the numerical simulations delineated in this section. It is crucial to show that the presented work is feasible and to use large-scale numerical simulation to verify the analytical work’s correctness. For a range of fractional values dependent on the steady-state point, the model numerical results are computed using Atangana-Baleanu in the Caputo sense in conjunction with Mittag-Leffler law. These simulations show how a change in value affects the model behavior. Furthermore, the results for fractional values demonstrate higher efficiency as compared to the usual derivative. It enables a more accurate estimation of the best amount for disease control. The actual parameters of the data are \(r = 2, d_1 = 0.5, d_2 = 1, d_3 = 1, d_4 = 1, k_1 = 1, k_2 = 0.1, k_3 = 1, k_4 = 0.5, k_5= 0.16, k_6= 0.45\)23. The nature of time in a days. The Kawasaki disease model dynamics for various values of \(t\in [0,10]\) are depicted in Figures 4a, 5a, 6a, and 7a, which use the Atangana-Baleanu type non-singular fractional derivative. Figures 4b, 5b, 6b, and 7b demonstrate the dynamics of the Kawasaki disease model for different values of \(t\in (0,1)\) using the non-singular fractional derivative of the Modified Atangana-Baleanu type. Figure 4 illustrates the E(t) dynamics for different fractional orders, showing that lower fractional orders correspond to increased endothelial cell populations over time. This could relate to heightened cellular proliferation from vascular endothelial growth factors, potentially leading to vascular issues seen in Kawasaki disease. This indicates the possibility of targeting endothelial proliferation to reduce vascular damage. The V(t) dynamics shown in Figure 5 indicate that as fractional orders \(\eta\) increase, the population of classes decreases. A decline in V(t) levels at higher fractional orders may dampen the growth and repair of vascular tissues, potentially weakening endothelial function and increasing vulnerability to inflammation. This suggests that V(t) modulation could be a therapeutic avenue, as lower V(t) may correlate with disease remission phases. The dynamics of C(t) are shown in Figure 6 for various fractional orders \(\eta\). Higher fractional orders lead to a continuous decrease in the population of classes and chemokine levels, indicating a reduced immune response in severe disease stages. This suggests that managing chemokine levels may influence immune cell recruitment, potentially helping to control inflammation and disease severity. Figure 7 shows that as the fractional order \(\eta\) decreases, the class population P(t) steadily rises. Inflammatory factors increase, particularly at lower fractional orders, indicating ongoing inflammation typical of Kawasaki disease. This persistent inflammation may lead to further vascular damage and greater disease severity, highlighting the need for early anti-inflammatory interventions. The trends in Figures 4, 5, 6, and 7 indicate that lower fractional orders result in heightened and sustained levels of inflammatory factors (P) and endothelial cells (E), suggesting more aggressive disease progression. Higher fractional orders reduce these levels, implying a dampening effect on inflammation. This implies that manipulating fractional orders could help modulate disease severity, offering potential control points for Kawasaki disease interventions. The crossover behavior in Figures 4, 5, 6, and 7 suggests a shift in the influence of fractional orders on the dynamics of each variable, reflecting transitions between different phases of Kawasaki disease. This behavior aligns with real-life disease progression, where initial inflammatory responses peak and later decline due to regulatory mechanisms. Such transitions validate the model’s ability to capture complex disease stages, confirming its realism and robustness for simulating Kawasaki disease dynamics. To demonstrate that fractional derivatives better capture Kawasaki disease dynamics, simulate both fractional and integer-order models. The fractional model shows a gradual decline in inflammation levels, reflecting the persistent inflammatory response in Kawasaki disease, while the integer model indicates a quicker decline. Compare to previous study23 simulations reveal that the fractional-order model exhibits more nuanced dynamics, such as delayed responses and complex transient behaviors, aligning better with real-world biological data. By comparing graphs, it is evident that the MABC model aligns more closely with realistic biological processes, making it a better choice for simulating complex disease dynamics like Kawasaki disease. For public health policy, these findings provide evidence that fractional-order models could improve predictions of Kawasaki disease outcomes and help design targeted therapies, especially during early stages. This model could guide resource allocation in clinical settings by highlighting which biological processes to monitor closely in Kawasaki disease patients.

Conclusion

We examine the interactions between different parameters in the Kawasaki disease model (8) in this article. We analyze the dynamic behavior of the system for constant controls by using the fractional operator Kawasaki disease model. We took into consideration the recently developed modified ABC operator in our proposed problem. The modified Atangana-Baleanu-Caputo operator offers advantages over the standard Atangana-Baleanu-Caputo operator in terms of well-posedness and initialization. The MABC operator addresses initialization issues present in the ABC operator, leading to more robust and reliable model simulations. This improved initialization contributes to a more accurate representation of Kawasaki disease dynamics. Consequently, the MABC operator provides a more effective framework for analyzing the model’s stability and control. We assert that this operator has afforded researchers a novel pathway for investigation within their scholarly endeavors. The application of Leray-Schauder method was employed to ascertain the existence of solutions. The examination of the global stability of the fractional order model is conducted through the utilization of the Lyapunov function. This new numerical method was developed and used for a Kawasaki disease mathematical model using Lagrange’s interpolation polynomial. We pointed out that the results are more realistic and that the approach can be used to examine dynamical systems in more detail. The effect of fractional order on the analysis of vaccination and community effects is demonstrated using a numerical simulation. According to this study, the ABC model yields less insightful results on compartmental population dynamics than the MABC fractional-order model. Therefore, it may be said that MABC is particularly useful for simulating real-world issues. Readers might review the imagined problem by using additional fixed-point approaches to see if there are multiple or unique solutions. Additionally, they might develop new numerical systems using other techniques. Future work could extend this model by incorporating additional biological complexities, such as immune system interactions, environmental factors, or genetic predispositions, to enhance its applicability to Kawasaki disease. The framework could also be adapted to model other diseases with similar dynamics, like rheumatoid arthritis or systemic vasculitis, by adjusting parameters and fractional orders. Exploring advanced numerical methods, such as adaptive or hybrid techniques, could improve computational efficiency and accuracy for complex systems. Collaborative efforts with clinical researchers could further validate and refine the model for real-world applications.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kawasaki, T., Kosaki, F., Okawa, S., Shigematsu, I. & Yanagawa, H. A new infantile acute febrile mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (MLNS) prevailing in Japan. Pediatrics 54(3), 271–276 (1974).

Newburger, J. W., Takahashi, M. & Burns, J. C. Kawasaki disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67(14), 1738–1749 (2016).

Newburger, J. W. et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: A statement for health professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Am. Heart Assoc. Circ. 110(17), 2747–2771 (2004).

Singh, S., Vignesh, P. & Burgner, D. The epidemiology of Kawasaki disease: A global update. Arch. Dis. Childhood 100(11), 1084–1088 (2015).

Gordon, J. B., Kahn, A. M. & Burns, J. C. When children with Kawasaki disease grow up: Myocardial and vascular complications in adulthood. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 54(21), 1911–1920 (2009).

Gordon, J. B. et al. The spectrum of cardiovascular lesions requiring intervention in adults after Kawasaki disease. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 9(7), 687–696 (2016).

Rosenkranz, M. E. et al. TLR2 and MyD88 Contribute to Lactobacillus casei extract-induced focal coronary arteritis in a mouse model of kawasaki disease. Circulation 112(19), 2966–2973 (2005).

Schulte, D. J. et al. Involvement of innate and adaptive immunity in a murine model of coronary arteritis mimicking Kawasaki disease. J. Immunol. 183(8), 5311–5318 (2009).

Rowley, A. H., Baker, S. C., Orenstein, J. M. & Shulman, S. T. Searching for the cause of Kawasaki disease-cytoplasmic inclusion bodies provide new insight. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6(5), 394–401 (2008).

Rowley, A. H. et al. Ultrastructural, immunofluorescence, and RNA evidence support the hypothesis of a “new” virus associated with Kawasaki disease. J. Infect. Dis. 203(7), 1021–1030 (2011).

Newburger, J. W. et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: A statement for health professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Am. Heart Assoc. Circ. 110(17), 2747–2771 (2004).

Tremoulet, A. H. et al. Resistance to intravenous immunoglobulin in children with Kawasaki disease. J. Pediatr. 153(1), 117–121 (2008).

Kato, H. et al. Long-term consequences of Kawasaki disease: A 10-to 21-year follow-up study of 594 patients. Circulation 94(6), 1379–1385 (1996).

Friedman, K. G. et al. Coronary artery aneurysms in Kawasaki disease: Risk factors for progressive disease and adverse cardiac events in the US population. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 5(9), e003289 (2016).

Burns, J. C. & Franco, A. The immunomodulatory effects of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in Kawasaki disease. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 11(7), 819–825 (2015).

Skochko, S. M. et al. Kawasaki disease outcomes and response to therapy in a multiethnic community: A 10-year experience. J. Pediatr. 203, 408–415 (2018).

Makino, N. et al. Nationwide epidemiologic survey of Kawasaki disease in Japan, 2015–2016. Pediatr. Int. 61(4), 397–403 (2019).

Takahashi, K., Oharaseki, T., Yokouchi, Y., Hiruta, N. & Naoe, S. Kawasaki disease as a systemic vasculitis in childhood. Ann. Vasc. Dis. 3(3), 173–181 (2010).

Takahashi, K., Oharaseki, T. & Yokouchi, Y. Histopathological aspects of cardiovascular lesions in Kawasaki disease. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 21(1), 31–35 (2018).

Brown, T. J. et al. CD8 T lymphocytes and macrophages infiltrate coronary artery aneurysms in acute Kawasaki disease. J. Infect. Dis. 184(7), 940–943 (2001).

Rowley, A. H., Eckerley, C. A., Shulman, J. H. M. & Baker, S. C. IgA plasma cells in vascular tissue of patients with Kawasaki syndrome. J. Immunol. 159(12), 5946–5955 (1997).

Rowley, Anne H. et al. IgA plasma cell infiltration of proximal respiratory tract, pancreas, kidney, and coronary artery in acute Kawasaki disease. J. Infect. Dis. 182(4), 1183–1191 (2000).

Leung, D. Y. et al. Two monokines, interleukin 1 and tumor necrosis factor, render cultured vascular endothelial cells susceptible to lysis by antibodies circulating during Kawasaki syndrome. J. Exp. Med. 164(6), 1958–1972 (1986).

Leung, D. M. et al. Endothelial cell activation and high interleukin-1 secretion in the pathogenesis of acute Kawasaki disease. The Lancet 334(8675), 1298–1302 (1989).

Caputo, M. Linear models of dissipation whose Q is almost frequency independent-II. Geophys. J. Int. 13(5), 529–539 (1967).

Caputo, M. & Fabrizio, M. A new definition of fractional derivative without singular kernel. Prog. Fract. Differ. Appl. 1(2), 73–85 (2015).

Atangana, A. & Baleanu, D. New fractional derivatives with nonlocal and non-singular kernel: Theory and application to heat transfer model. Therm. Sci. 20(2), 763–9 (2016).

Al-Refai, M. & Baleanu, D. On an extension of the operator with Mittag-Leffler kernel. Fractals 30(05), 2240129 (2022).

Farman, M., Jamil, K., Xu, C., Nisar, K. S. & Amjad, A. Fractional order forestry resource conservation model featuring chaos control and simulations for toxin activity and human-caused fire through modified ABC operator. Math. Comput. Simul. 227, 282–302 (2024).

Jamil, S., Naik, P. A., Farman, M., Saleem, M. U. & Ganie, A. H. Stability and complex dynamical analysis of COVID-19 epidemic model with non-singular kernel of Mittag-Leffler law. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 70, 3441 (2024).

Nisar, K. S., Farman, M., Abdel-Aty, M. & Ravichandran, C. A review of fractional order epidemic models for life sciences problems: Past, present and future. Alex. Eng. J. 95, 283–305 (2024).

Khan, A. et al. Fractional dynamics and stability analysis of COVID-19 pandemic model under the harmonic mean type incidence rate. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 25(6), 619–640 (2022).

Khan, A. et al. Modeling and sensitivity analysis of HBV epidemic model with convex incidence rate. Results Phys. 22, 103836 (2021).

Zarin, R., Khan, A. & Akg, L. A. Fractional modeling of COVID-19 pandemic model with real data from Pakistan under the ABC operator. AIMS Math. 7(9), 15939–15964 (2022).

Yu, D., Liao, X. & Wang, Y. Modeling and analysis of Caputo Fabrizio definition-based fractional-order boost converter with inductive loads. Fractal Fract. 8(2), 81 (2024).

Xu, K. et al. Fractional-order Zener model with temperature-order equivalence for viscoelastic dampers. Fractal Fract. 7(10), 714 (2023).

Ali, Z., Rabiei, F., Rashidi, M. M. & Khodadadi, T. A fractional-order mathematical model for COVID-19 outbreak with the effect of symptomatic and asymptomatic transmissions. Eur. Phys. J.Plus 137(3), 395 (2022).

Farman, M., Shehzad, A., Nisar, K. S., Hincal, E. & Akgul, A. A mathematical fractal-fractional model to control tuberculosis prevalence with sensitivity, stability, and simulation under feasible circumstances. Comput. Biol. Med. 178, 108756 (2024).

Xu, C. et al. New results on bifurcation for fractional-order octonion-valued neural networks involving delays. Netw. Comput. Neural Syst. https://doi.org/10.1080/0954898X.2024.2332662 (2024).

Xu, C. et al. Bifurcation investigation and control scheme of fractional neural networks owning multiple delays. Comput. Appl. Math. 43(4), 1–33 (2024).

Khan, H., Alzabut, J., Alfwzan, W. F. & Gulzar, H. Nonlinear dynamics of a piecewise modified ABC fractional-order leukemia model with symmetric numerical simulations. Symmetry 15(7), 1338 (2023).

Khan, H., Alzabut, J., G-Aguilar, J. F. & Alkhazan, A. Essential criteria for existence of solution of a modified-ABC fractional order smoking model. Ain Shams Eng. J. 15(5), 102646 (2024).

Khan, H., Alzabut, J., Almutairi, D. K. & Alqurashi, W. K. The use of artificial intelligence in data analysis with error recognitions in liver transplantation in HIV-AIDS patients using modified ABC fractional order operators. Fractal Fract. 9(1), 16 (2024).

Khan, H., Alzabut, J., Baleanu, D., Alobaidi, G. & Rehman, M. U. Existence of solutions and a numerical scheme for a generalized hybrid class of n-coupled modified ABC-fractional differential equations with an application. (2023).

Paul, S., Mahata, A., Mukherjee, S. & Roy, B. Dynamics of SIQR epidemic model with fractional order derivative. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 5, 100216 (2022).

Dano, L. B., Koya, P. R. & Keno, T. D. Fractional optimal control strategies for hepatitis B virus infection with cost-effectiveness analysis. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 19514 (2023).

Al-Refai, M. & Baleanu, D. On an extension of the operator with Mittag-Leffler kernel. Fractals 30(05), 2240129 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported via funding from Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University project number (PSAU/2025/R/1446).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nisar, K.S., Farman, M., Jamil, K. et al. Synchronization and dynamics of modified fractional order Kawasaki disease model with chaos stability control. Sci Rep 15, 25953 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09944-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09944-6