Abstract

Mammography is important for breast cancer detection, and calcifications and masses are the most common mammographic features. In this exploratory study, we evaluated the association between these findings and immune gene expression to determine the role that inflammation may play in mass- or calcification-associated breast cancers. This study included 205 breast cancer patients in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study and the Carolina Mammography Registry. Hierarchical clustering and logistic regression were used to examine associations between radiologist-reported imaging features and tumor RNA expression of 48 immune-related genes. The Bonferroni correction adjusted for multiple comparisons. There were statistically significant associations between CCL7 and calcifications (odd ratio [OR] = 0.52, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.35, 0.75) and between CCL7 and the presence of a mass (OR = 1.48 95% CI = 1.18, 1.88). Furthermore, lower expression of genes with anti-inflammatory function was associated with calcifications (p = 0.04), but not masses. However, neither mammographic masses nor calcifications were associated with global gene expression patterns using hierarchical clustering. This analysis of bulk immune markers suggests plausible associations between immune alterations and mammographic findings. Larger studies and immunoprofiling approaches sensitive to subtle variation should be conducted to identify targetable imaging characteristics, which alongside immunotherapeutic advances, may facilitate targeted breast cancer treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Calcifications and masses play important roles in the radiographic detection of breast cancer1, and there is evidence that these features may be related to underlying tumor biology. Calcifications have been associated with an increased recurrence rate and decreased survival among women diagnosed with breast cancer2,3,4,5,6,7. Calcifications are also more prevalent among tumors that are higher histologic grade2,4,6,7,8,9,10, smaller size8,9,10,11, lymph node-positive2, hormone receptor-negative4,7,12, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive4,7,11. Inflammatory cells such as macrophages make up as much as half of the cell mass in some breast tumors13. Additionally, the presence of a mass on mammography is associated with estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2 negativity, and data suggest that larger tumor mass on imaging may be associated with decreased metastasis-free survival. There are several hypotheses that may explain these relationships. However, it is not known whether mammographic calcifications or masses are associated with specific immune gene expression patterns in breast tumors.

A tumor’s immune microenvironment is an important factor in breast cancer, with recognition of its role in breast carcinogenesis14,15, disease progression16,17,18, and as a therapeutic target for some breast cancers19,20. Specifically, elevated expression of immune checkpoint genes PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 is associated with response to the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab, which is FDA-approved for treatment of triple-negative breast cancer19,20,21. With other forms of immunotherapy such as cancer vaccines and CAR-T cell therapy under investigation19, understanding the inflammatory pathways that mediate a tumor’s response to immunotherapy is important for translation of those therapies to breast cancer.

Some studies suggest that calcifications are inversely associated with immune system activity22,23, a hypothesis supported by a whole transcriptome analysis showing decreased activity of inflammatory pathways in breast tumors with calcifications23. To our knowledge, associations between mammographic masses and inflammatory gene expression have not been reported. Therefore, in this exploratory analysis, we examined expression of 48 genes related to immune response in relation to mammographic presence of a mass or calcifications. Our goal was to understand the potential mechanistic link between tumor biology and mammographic features. This understanding may suggest a tumor’s immune response at the time of detection, informing identification of patients who may benefit from an expedited workup for immunotherapy.

Materials and methods

Study population

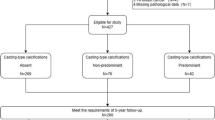

This study used data from the Carolina Breast Cancer Study (CBCS) and Carolina Mammography Registry (CMR), both of which have been described previously24,25. Briefly, the CBCS is a population-based study of breast cancer among women aged 20 to 74 years in central and eastern North Carolina. Invasive breast cancer cases were identified using rapid case ascertainment, where pathology reports with a breast cancer diagnosis were identified by healthcare facilities and sent directly to researchers within months of diagnosis26, between 1993–2001 (CBCS 1 and CBCS 2) and 2008–2013 (CBCS 3). The CMR is a community-based breast imaging registry that collects data on breast imaging exams at participating facilities across North Carolina. Probabilistic linkage methods were used to merge CBCS and CMR data27, resulting in 4806 CBCS cases with mammographic data in the CMR (Fig. 1).

Inclusion criteria. The data represent women who were included in two population based studies, the Carolina Breast Cancer Study (CBCS) and the Carolina Mammography Registry (CMR). The final analysis included 205 women for whom tumor gene expression analyses were completed and who had a recent mammogram conducted at a facility that characterized mammographic findings. Number of cases with each combination of mammographic findings is displayed.

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. CBCS data was collected with patients’ written informed consent and CMR data were collected under a waiver of informed consent. The current study was reviewed by the University of North Carolina School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and determined to be exempt from further review.

Immune gene expression

Expression levels of a validated set of 48 genes representative of adaptive and innate immune function were measured from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor tissue of a sub-set of CBCS participants with invasive breast cancer using the Nanostring nCounter assay28,29. Tumor samples were collected prior to cancer treatment. The immune functions of these genes were originally reported by Danaher et al.30, Bindea et al.31, and Sakuishi et al.32, and their expression in the CBCS has been described in detail29. Briefly, expression data were cleaned and normalized based on housekeeping gene expression levels as previously described33 using the Remove Unwanted Variation Bioconductor package, RUVseq34. Cell type-specific scores were calculated based on the median log2 expression among genes of the same type (B cell, CD8 T cell, T cell, T helper cell, T follicular helper cell [Tfh], T regulatory cell [Treg], natural killer cell, eosinophil, macrophage, neutrophil, or cytotoxic cell)29. Global immune class (innate, adaptive, immune quiet) was categorized based on clusters originally defined in the CBCS and validated in The Cancer Genome Atlas data29.

Mammographic features

Screening and diagnostic mammograms within a 37-month period ranging from three years prior to one month after the date of breast cancer diagnosis were eligible for inclusion. Mammographic findings, including calcifications and masses, were reported at the time of the mammogram by a radiologist using a rating system based on the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) schema35. A numeric rating was recorded separately for each type of finding in each breast, distinct from the overall BI-RADS assessment of the mammogram. We used a binary classification to define the presence of the mammographic finding in the breast where cancer was diagnosed, where an assessment of 0 (needs additional imaging evaluation), 2 (benign), 3 (probably benign), 4 (suspicious), or 5 (highly suggestive of malignancy) indicated the finding was present and an assessment of 1 (negative) indicated the finding was absent. There were no BI-RADS 6 (biopsy-diagnosed cancer) assessments in the study population. Some women had multiple mammograms during the study period. In cases where women had multiple mammograms, the imaging finding was classified as present if any mammogram of the cancer-affected breast had a finding-specific assessment of 0, 2, 3, 4, or 5 during the study period.

Covariates

Participant personal and health history information, including age, menopausal status, race, family history of breast cancer, reproductive history, medication use, alcohol use, and smoking status, were self-reported in the CBCS using a standardized questionnaire conducted by a trained nurse-interviewer, on average within 6 months following the date of diagnosis. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from height and weight measurements obtained at the time of the CBCS study interview. Tumor characteristics, including stage at diagnosis and hormone receptor status, were abstracted from medical records. Participants provided informed consent for CBCS study access to tumor blocks. PAM50 molecular subtype was measured from archival tumor tissue and used to classify tumors into Luminal A, Luminal B, Basal-like, HER2-enriched, or normal-like subtypes, as described previously28,29.

Analytic population

Cases were excluded from this analysis if they lacked gene expression data, lacked a mammogram within three years prior to or one month after the date of diagnosis, or the mammogram was performed at a facility that did not characterize mammographic findings in detail (Fig. 1). A total of 205 women were included in the analysis. Included cases were similar to the overall case population with respect to demographics and tumor characteristics (data not shown).

Statistical analysis

Genes were classified as pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory based on the literature (Supplementary Table S1 online), and mean expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory genes was computed for each subject. Difference in means and associated two-sided 95% CIs for associations between mean pro- or anti-inflammatory gene expression and presence of each mammographic finding was estimated and a difference between groups was evaluated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Unsupervised clustering using the ComplexHeatmap package in R was used to explore whether genes were differentially expressed between samples with and without calcifications36. A similar analysis was conducted using this package to explore whether genes were differentially expressed between samples with and without masses. As an additional sensitivity analysis, we repeated the unsupervised clustering while limiting the analysis to luminal A and luminal B tumors to ensure that the results were not being driven by tumor subtype. Basal-like, HER2-enriched, and normal-like tumors were too small in number for separate clustering analyses.

Univariate logistic regression was used to compute odds ratios (OR) and two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CI) for associations between normalized gene expression level and presence of mammographic calcifications as well as mammographic masses. ORs were estimated for each of the 10 cell types in addition to individual genes. Nominal logistic regression was used to estimate association with gene expression when the outcome considered joint presence of imaging findings, categorized as: both calcifications and mass, mass only, calcifications only, or neither finding (referent group).

As a sensitivity analysis, we conducted supervised clustering using the R package Limma to determine whether the joint presence of a mass and calcifications had any effect on immune gene expression patterns37. We additionally evaluated individual gene associations with imaging findings that were considered suspicious for malignancy (BI-RADS rating of 4 or 5). Another sensitivity analysis was performed which considered only imaging findings present on the patient’s last chronological mammogram.

Hamilton et al. 2022 describe three immune classes based on clustering of gene expression in tumor samples from this dataset29: immune quiet, with the lowest overall immune gene expression; innate enriched, with the highest expression of genetic markers for eosinophils and neutrophils; and adaptive enriched, with the highest overall expression and highest expression of genes involved in adaptive immunity. Fisher’s exact test was used to estimate p-values for associations between immune class and presence of a mass or calcifications.

Statistical analyses were performed using R. All p-values were two-sided. The Bonferroni correction was used to control for multiple comparisons, with adjusted α-levels of 0.001 for imaging finding associations with individual gene expression and 0.005 for associations with cell type scores.

Results

Study population

A total of 205 breast cancer patients were included in the analysis. Among them, 25 (12%) had calcifications and 96 (47%) had a mass visible on a mammogram of the breast affected by cancer (Fig. 1). A mass was more common among patients who were African American, had a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2, were younger than 50 years old, or whose tumors were ER-negative, basal-like, or HER2-enriched (Table 1). The presence of calcifications was not associated with any of the participant characteristics examined (Table 1). Additionally, the presence of calcifications was not associated with the presence of a mass (Table 1).

Association of inflammatory markers with mammographic features

Mean expression of anti-inflammatory genes was lower for tumors in the presence of mammographic calcifications when compared with tumors without calcifications (Fig. 2a, difference [95% CI] − 0.23 [-0.41, − 0.05], p = 0.04;). Expression of pro-inflammatory genes was also lower in the presence of calcifications, although this result was not statistically significant (Fig. 2b difference [95% CI] − 0.17 [-0.34, 0.01], p = 0.09). There was no significant association between the presence of a mass and mean expression of anti-inflammatory genes (Fig. 2c, difference [95% CI] 0.13 [-0.028, 0.28] p = 0.17) or pro-inflammatory genes (Fig. 2d, difference [95% CI] 0.02 [-0.12, 0.16], p = 0.46). When the association between pro-inflammatory gene expression and calcifications was studied across the four possible combinations of findings, the association was limited to patients with both calcification and mass compared to neither calcification nor mass (Supplementary Figure S1 online).

Box plots depicting the mean log2 gene expression of inflammatory marker genes in 205 breast tumors according to the presence or absence of a mammographic calcifications (panels a and b) or the presence or absence of a mammographic mass (panels c and d). The p-values provided represent Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Genes were divided according to likely function as inhibiting inflammation (panels a and c) or promoting inflammation (panels b and d).

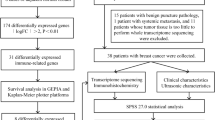

Gene expression patterns yielded three distinct clusters, recapitulating previously reported adaptive-enriched, innate-enriched, and immune quiet phenotypes (Fig. 3a). There was no association between global immune class and the presence of calcifications or a mass (Table 2). When the clustering analysis was limited to the luminal subtype, a similar pattern of clustering by global immune class was observed (Fig. 3b). Calcifications and masses were not associated with global immune class among luminal cancers.

Heatmaps representing relative expression of inflammatory marker genes generated by unsupervised clustering based on similarity in expression pattern. Immune class, intrinsic subtype, calcification status, mass status, and mean immune gene expression level of each sample is depicted above the heatmap. Immune class color boundaries delineate three distinct clusters. All breast cancers are shown in panel a (N = 205). Luminal A & B subtype breast cancers are shown in panel b (N = 123). Asterisks (*) indicate rows corresponding to expression of CCL7.

When we analyzed expression of individual genes, several were associated with the presence of a mass or calcifications at the nominal alpha-level of 0.05 (Table 3). CD6 (T cell) and FOXP3 (Treg) were positively associated with the presence of a mass, whereas CD4 (Thelper), FN1 (macrophage) and MSR1 (macrophage) were inversely associated with the presence of a mass. LCK (T cell) and FOXP3 (Treg) were inversely associated with the presence of calcifications. Following adjustment for multiple comparisons, the macrophage marker CCL7 remained inversely associated with the presence of calcifications (OR = 0.52 [95% CI 0.35, 0.75]; p < 0.01) and positively associated with the presence of a mass (OR = 1.48 [95% CI 1.18, 1.88]; p < 0.01) (Table 3). A similar association was observed with supervised clustering, which showed that CCL7 was differentially expressed between samples with a mass only when compared to samples with neither mass nor calcification (p < 0.01). When evaluated according to joint mass and calcification status, CCL7 expression in the presence of both mass and calcification was similar to CCL7 expression in the presence of calcifications only (Supplementary Figure S2 online).

We conducted several additional analyses to better characterize relationships between CCL7 expression, calcifications, and masses. For 15 patients with calcifications and 87 patients with a mass, the imaging finding was rated by a radiologist as being suspicious for malignancy. When we restricted our analysis to those suspicious imaging findings, CCL7 associations with the presence of a mass and presence of calcifications were still observed (Supplementary Table S2 online). Additionally, stratifying by ER status, PR status, PAM50 subtype, or stage at diagnosis did not substantially alter the associations between CCL7 expression and mammographic calcifications or masses (Supplementary Table S3 online).

To evaluate the effect of differences in the length of time between the mammogram exam and breast cancer diagnosis on our results, we restricted the analysis to patients who had a mammogram within 100 days of breast cancer diagnosis. Consistent with the pattern in all patients, CCL7 was expressed at lower levels in the presence of calcifications (OR = 0.54 [95% CI 0.31, 0.92]; p = 0.02) and at higher levels in the presence of a mass (OR = 1.61 [95% CI 1.13, 2.28]; p < 0.01 Additionally, 7 (28%) patients with calcifications and 13 (14%) of patients with masses had subsequent mammograms where the findings were given a finding-specific BI-RADS rating of 1 (negative) by the radiologist. When considering only findings present on a patient’s last chronological mammogram, CCL7 expression remained lower in the presence of calcifications (OR = 0.57 [95% CI 0.38, 0.85], p < 0.01) and higher in the presence of a mass (OR = 1.47 [95% CI 1.16, 1.86], p < 0.01). We also considered potential for confounding by factors associated with the presence of calcifications or presence of a mass (Table 1). Though no covariates were significantly associated with calcifications, Age, race, BMI, ER status, and PAM50 subtype were associated with the presence of a mass. Of these, only ER status and PAM50 subtype were also associated with CCL7 expression level. When we adjusted for ER status and PAM50 subtype, CCL7 remained significantly associated with the presence of a mass though the resulting odds ratio was attenuated (OR = 1.39 [95% CI 1.09, 1.78), p = < 0.01).

When expression levels were grouped according to their associated cell type, the Treg cell type was positively associated with the presence of a mass and the presence of a mass suspicious for malignancy, but the associations did not reach statistical significance after adjustment for multiple comparisons (Table 3, Supplementary Table S2 online). Other cell type scores were not associated with the mammographic findings.

Discussion

The present work is an exploratory investigation into the relationship between breast tumor expression of genes related to inflammation and mammographic features. Most of the genes evaluated were expressed at lower levels in tumor samples from breasts with mammographic calcifications, which is consistent with previous work showing decreased inflammatory activity in breast cancers with calcifications23. Shin et al.23 analyzed expression of 2551 genes in 168 breast tumor samples and demonstrated that inflammatory pathways were less active in tumor samples from breasts with mammographic calcifications. However, they analyzed gene expression aggregated by function and did not study individual genes. Our work corroborates the association between decreased inflammation and calcifications and extends it by examining 48 individual genes known to be involved in inflammatory pathways. We also evaluated mammographically apparent masses, which, to our knowledge, have not been studied in relation to inflammatory gene expression.

Genes related to inflammatory activity were suppressed in tumors in the presence of calcifications. Our data suggest a subtle, balanced reduction in overall inflammatory gene expression. This may result from a lower number of inflammatory cells relative to other cell types in tumors associated with calcification or decreased transcriptional activity of inflammatory cells within these tumors. Because the magnitude of associations did not change substantially when stratified by tumor characteristics, the observed associations are unlikely to result from differences in prognostic features between patients with and without calcifications.

CCL7 was the only gene for which associations with either mammographic finding were statistically significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons. CCL7 is a chemokine secreted by macrophages and attracts other immune cells to a site of inflammation. CCL7 has been shown to promote tumor progression in numerous cancers, including breast cancer38. Our finding that higher CCL7 expression is associated with the presence of a breast mass is consistent with the idea that breast cancers presenting with a mass may have an associated inflammatory response. However, our observation of lower CCL7 expression in the presence of calcifications, which would produce a muted inflammatory response, is not consistent with the hypothesis that the association between calcifications and poorer breast cancer survival is mediated by inflammation2,3,5,16,17. It is possible that more nuanced relationships among individual genes within inflammatory pathways explain the association between calcifications and survival.

Calcifications were associated with lower expression of pro-inflammatory gene CCL7 in tumors with and without a mass. It is possible that these results reflect false-positive findings. However, these associations remained significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons. The greater magnitude of association in patients with a mass raises the possibility that the presence of a mass modifies the association between calcifications and gene expression. Notably, our supervised clustering analysis demonstrated differential expression in CCL7 between tumors with masses and those with neither mass nor calcification but did not demonstrate differential expression in tumors with calcification. This discrepancy may be the result of an under-powered analysis, as few tumors had calcification only.

Associations for several other inflammatory genes failed to reach statistical significance after adjusting for multiple comparisons. In addition, there was no clear pattern implicating a particular cell type in the relationship between inflammatory gene expression and mammographic findings. When we used the cell type score to summarize information according to cell function, the association between expression of Treg-related genes and the presence of a mass was nominally statistically significant, suggesting that these genes were expressed at higher levels in tumors that presented with a mass. As regulatory T-cells are predominantly anti-inflammatory39, it is plausible that such an association may be the result of an immune response to the presence of the tumor. Further studies that can accurately measure the timing of immune response during tumor development are necessary to confirm such a relationship.

Understanding relationships between a tumor’s inflammatory microenvironment and mammographic findings may have clinical relevance as immunotherapy becomes widely available. Currently, immune checkpoint inhibitors that target PD-L1 and PD-1 are FDA-approved for triple-negative breast cancer19,20,21. While PD-L1 was not associated with mammographic findings in this study, the gene we found to be differentially expressed, CCL7, may play an important role in the success of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. In lung cancer models, CCL7 was shown to recruit CD8 + T cells to facilitate antitumor immunity, higher levels of CCL7 were associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor response, and administration of CCL7 decreased tumor progression and prolonged survival40. If confirmed in breast cancer, this raises the possibility that immunoreactive tumors may be detectable from mammographic findings, warranting faster workup for molecular confirmation in those patients. With more thorough characterization of these associations, mammography may help identify patients likely to benefit from additional clinical workup for immunotherapy.

There are several limitations in the present study. Foremost, the small sample size limited statistical power for analyses of specific tumor subtypes or the presence of masses and calcifications with specific BI-RADS assessments. Consequently, this analysis may have missed associations that could be detected in a larger population. Our analysis focused on the presence of calcifications and masses in the breast affected by cancer, but radiologic-pathologic correlation was not performed to confirm that the mammographic finding and the tumor were in the same location within the breast. As a result, it is possible that some mammographic findings we observed were not physically associated with the tumor. Additionally, there was some variability in mammography timing relative to cancer diagnosis, and it is possible our initial analysis failed to detect changes in imaging findings over time. To address this, we demonstrated consistent associations of CCL7 with mammographic findings when restricting our analysis to mammograms within 100 days of cancer diagnosis, and when considering imaging findings on the patient’s last mammogram. Not all mammographic facilities reported detailed data on imaging findings. We used bulk profiling to measure gene expression rather than spatial profiling or immunohistochemistry, both of which can be more sensitive for rare cell types infiltrating tumors. Though common, the gene-level approach we used in this exploratory study does not consider marker co-expression within a given cell type, may be influenced by non-specific gene expression, is sensitive to the choice and number of markers, and may not accurately reflect cell type abundance. Future work should leverage immunofluorescence markers for specific cell types, with the insight from the current work providing suggestive data that immune fluctuation may be linked to mammographic features.

These limitations were balanced by several strengths. We leveraged existing observational studies to conduct a novel assessment of inflammatory patterns associated with mammographic features in a diverse population. The two linked studies herein have rigorous data collection processes and include radiologist-reported assessments of mass and calcifications using a standardized scale, and comprehensive characterization of tumor prognostic characteristics, including PAM50 molecular subtype. Gene expression was measured in tumor tissue that was obtained prior to cancer treatment, ensuring that the observed expression patterns are not due to the type of therapy received. The genes studied have been extensively evaluated as markers for the inflammatory cell types evaluated in this analysis30,31,32. We used multiple analytic approaches to ensure the robustness of our results and separated the genes by likely pro- or anti-inflammatory function and cell type to increase the biological relevance of the groupings.

In summary, gene expression patterns indicated that the presence of calcifications may be associated with lower breast tumor inflammatory activity. Specific immune cell types or immune phenotypes were not implicated, but expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine CCL7 was lower when calcifications were present and higher when a mass was present. If confirmed, these findings suggest that, in principle, imaging characteristics may have value for predicting tumor immune microenvironments, with increasing relevance as immunotherapy becomes more widely utilized.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available to maintain patient privacy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Venkatesan, A., Chu, P., Kerlikowske, K., Sickles, E. A. & Smith-Bindman, R. Positive predictive value of specific mammographic findings according to reader and patient variables. Radiology 250, 648–657. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2503080541 (2009).

Tabar, L. et al. Mammographic tumor features can predict long-term outcomes reliably in women with 1–14-mm invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer 101, 1745–1759. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20582 (2004).

Thurfjell, E., Thurfjell, M. G. & Lindgren, A. Mammographic finding as predictor of survival in 1–9mm invasive breast cancers. Worse prognosis for cases presenting as calcifications alone. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 67, 177–180. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1010648919150 (2001).

Pálka, I., Ormándi, K., Gaál, S., Boda, K. & Kahán, Z. Casting-type calcifications on the mammogram suggest a higher probability of early relapse and death among high-risk breast cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 46, 1178–1183. https://doi.org/10.1080/02841860701373611 (2007).

Ling, H. et al. Malignant calcification is an important unfavorable prognostic factor in primary invasive breast cancer. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 9, 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-7563.2012.01572.x (2013).

Tabar, L. T. et al. A novel method for prediction of long-term outcome of women with T1a, T1b, and 10–14 mm invasive breast cancers: A prospective study. The Lancet 355, 429–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)82008-5 (2000).

Mansson, E., Bergkvist, L., Christenson, G., Persson, C. & Wã¤Rnberg, F. Mammographic casting-type calcifications is not a prognostic factor in unifocal small invasive breast cancer: A population-based retrospective cohort study. Journal of Surgical Oncology 100, 670–674. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.21405 (2009).

James, J. et al. Is the presence of mammographic comedo calcification really a prognostic factor for small screen-detected invasive breast cancers?. Clin. Radiol. 58, 54–62. https://doi.org/10.1053/crad.2002.1110 (2003).

Evans, A., Pinder, S., James, J., Ellis, I. & Cornford, E. Is mammographic spiculation an independent, good prognostic factor in screening-detected invasive breast cancer?. Am. J. Rotengol. 187, 1377–1380. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.05.0725 (2006).

Nyante, S. J., Lee, S. S., Benefield, T. S., Hoots, T. N. & Henderson, L. M. The association between mammographic calcifications and breast cancer prognostic factors in a population-based registry cohort. Cancer 123, 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30281 (2017).

Gajdos, C. et al. Mammographic appearance of nonpalpable breast cancer reflects pathologic characteristics. Ann. Surg. 235, 246–251. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-200202000-00013 (2002).

Shin, H. J. et al. Correlation between mammographic and sonographic findings and prognostic factors in patients with node-negative invasive breast cancer. Br. J. Radiol. 84, 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr/92960562 (2011).

Obeid, E., Nanda, R., Fu, Y.-X. & Olopade, O. I. The role of tumor-associated macrophages in breast cancer progression. Int. J. Oncol. 43, 5–12. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2013.1938 (2013).

Takeuchi, Y. & Gotoh, N. Inflammatory cytokine-enriched microenvironment plays key roles in the development of breast cancers. Cancer Sci. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.15734 (2023).

Crump, L., Kines, K., Richer, J. & Lyons, T. Breast cancers co-opt normal mechanisms of tolerance to promote immune evasion and metastasis. Am. J. Cell Physiol. 323, C1475–C1495. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00189.2022 (2022).

Ham, M. & Moon, A. Inflammatory and microenvironmental factors involved in breast cancer progression. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 36, 1419–1431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12272-013-0271-7 (2013).

Takeuchi, H. et al. Comparison of the prognostic values of preoperative inflammation-based parameters in patients with breast cancer. PLoS ONE 12, e0177137. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177137 (2017).

Villarreal-García, V. et al. A vicious circle in breast cancer: The interplay between inflammation, reactive oxygen species, and microRNAs. Front. Oncol. 12, 980694. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.980694 (2022).

Debien, V. et al. Immunotherapy in breast cancer: an overview of current strategies and perspectives. npj Breast Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-023-00508-3 (2023).

Jacob, S. L., Huppert, L. A. & Rugo, H. S. Role of immunotherapy in breast cancer. JCO Oncol. Pract. 19, 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1200/op.22.00483 (2023).

Sun, X. & Zhang, T. Identification of immune-related signature for the prognosis and benefit of immunotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer. Front. Genet. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.1067254 (2022).

Tse, G. M., Tan, P.-H., Cheung, H. S., Chu, W. C. W. & Lam, W. W. M. Intermediate to highly suspicious calcification in breast lesions: A radio-pathologic correlation. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 110, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-007-9695-4 (2008).

Shin, S. U. et al. Gene expression profiling of calcifications in breast cancer. Sci. Rep.. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11331-9 (2017).

Yankaskas, B., Jones, M. & Aldrich, T. The Carolina Mammography Registry: A population-based mammography and cancer surveillance project. J. Registry Manag. 23, 175–178 (1996).

Newman, B. et al. The carolina breast cancer study: Integrating population-based epidemiology and molecular biology. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 35, 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00694745 (1995).

Rapid Case Ascertainment, <https://unclineberger.org/rapid-case-ascertainment/> (2022).

Puvanesarajah, S. et al. PAM50 and risk of recurrence scores for interval breast cancers. Cancer Prev. Res. 11, 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.capr-17-0368 (2018).

Troester, M. A. et al. Racial differences in pam50 subtypes in the carolina breast cancer study. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 110, 176–182. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djx135 (2018).

Hamilton, A. et al. The landscape of immune microenvironments in racially diverse breast cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 31, 1341–1350. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965 (2022).

Danaher, P. et al. Gene expression markers of tumor infiltrating leukocytes. J. ImmunoTher. Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40425-017-0215-8 (2017).

Bindea, G. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer. Immunity 39, 782–795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.003 (2013).

Sakuishi, K. et al. TIM3+FOXP3+regulatory T cells are tissue-specific promoters of T-cell dysfunction in cancer. OncoImmunology 2, e23849. https://doi.org/10.4161/onci.23849 (2013).

Bhattacharya, A. et al. An approach for normalization and quality control for NanoString RNA expression data. Brief Bioinform. 22, 163 (2021).

Risso, D., Ngai, J., Speed, T. P. & Dudoit, S. Normalization of RNA-seq data using factor analysis of control genes or samples. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 896–902. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2931 (2014).

D'Orsi, C. J., Sickles, E. A., Mendelson, E. B. & Morris, E. A. (American College of Radiology, Reston, VA, 2013).

Gu, Z. Complex heatmap visualization. iMeta. https://doi.org/10.1002/imt2.43 (2022).

Ritchie, M. et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv007 (2015).

Liu, Y., Cai, Y., Liu, L., Wu, Y. & Xiong, X. Crucial biological functions of CCL7 in cancer. PeerJ 16, e4928. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4928 (2018).

Hori, A., Nomura, T. & Sakaguchi, S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science 299, 1057–1061. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1079490 (2003).

Zhang, M. et al. CCL7 recruits cDC1 to promote antitumor immunity and facilitate checkpoint immunotherapy to non-small cell lung cancer. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19973-6 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the study participants, staff, and healthcare facilities who contributed to the data used in this study. Additionally, the authors would like to acknowledge the UNC Cancer Information & Population Health Resource (CIPHR) for performing the data linkage. The Carolina Mammography Registry is funded by the NCI (P01CA154292 and U01CA70040). The CBCS is supported by funds from UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center and the University Cancer Research Fund of North Carolina; the Susan G. Komen Foundation (OGUNC1202 and TREND21686258); and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) (P01CA151135 and P50CA058223). The CBCS recruited participants and/or obtained data with the assistance of Rapid Case Ascertainment, a collaboration between the North Carolina Central Cancer Registry and UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. Rapid Case Ascertainment is supported by the NIH (P30CA016086). Dr. Hamilton was supported by the Cancer Control Education Program at Lineberger Cancer Center (T32CA057726) and L60CA284495 from NCI. Funding organizations had no role in the design or interpretation of this study.

Funding

The Carolina Mammography Registry is funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) (P01CA154292 and U01CA70040). The CBCS is supported by funds from UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center and the University Cancer Research Fund of North Carolina; the Susan G. Komen Foundation (OGUNC1202 and TREND21686258); and the NCI (P01CA151135 and P50CA058223). The CBCS recruited participants and/or obtained data with the assistance of Rapid Case Ascertainment, a collaboration between the North Carolina Central Cancer Registry and UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. Rapid Case Ascertainment is supported by the National Institutes of Health (P30CA016086). AMH is supported by the Cancer Control Education Program at Lineberger Cancer Center (T32CA057726) and L60CA284495 from NCI. Funding organizations had no role in the design or interpretation of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study concept and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by M. T., A. H., and L. H. Analysis and preparation of the first draft of the manuscript were performed by N. S. and S. N. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This is an observational study. The University of North Carolina School of Medicine Institutional Review Board has reviewed this study and determined it to be exempt from further review.

Consent to participate

Carolina Breast Cancer Study participants provided written informed consent. Carolina Mammography Registry data were collected under a waiver of informed consent. Participants provided informed consent for study access to tumor blocks.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shaul, N.C., Troester, M.A., Hamilton, A.M. et al. Exploring associations between breast tumor inflammatory gene expression and mammographic calcifications and masses in a community-based population. Sci Rep 15, 28710 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09972-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09972-2