Abstract

Greenhouse gases, particularly CO2 and CH4, are key contributors to climate change and global warming. Consequently, effective management and reduction of these emissions, especially in subsurface storage applications, are crucial. Adsorption presents a promising strategy for mitigating CO2 and CH4 emissions in the energy sector, particularly in the storage and utilization of fossil fuel resources, thereby minimizing the environmental impact of their extraction and consumption. In this study, the adsorption behavior of CO2 and CH4 in tight reservoirs is examined using experimental data and advanced machine learning (ML) techniques. The dataset incorporates key variables such as temperature, pressure, rock type, total organic carbon (TOC), moisture content, and the CO2 fraction in the injected gas. Various ML models were employed to predict gas adsorption capacity, with CatBoost and Extra Trees demonstrating high predictive performance. The CatBoost model achieved superior results, with R² values of 0.9989 for CO₂ and 0.9965 for CH₄, along with low RMSE and MAE values, indicating strong stability and accuracy across all metrics. Sensitivity analysis identified pressure as the most influential factor, followed by TOC and CO2 percentage, while temperature had a restrictive effect on adsorption. Secondary variables, such as rock type and moisture content, also contributed, though to a lesser extent. Graphical analyses further validated the high accuracy of the ML models, particularly CatBoost and Extra Trees. The findings underscore the effectiveness of ML approaches and optimized hyperparameter tuning in enhancing the prediction of gas adsorption capacity, thereby improving the design of gas injection and storage processes. This research provides valuable insights for optimizing gas composition and operational parameters in storage applications, serving as a foundation for future studies in gas sequestration and reservoir engineering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The adsorption process is a critical component in material purification and separation, offering a cost-effective and efficient solution for addressing environmental challenges1. Gas adsorption, in particular, plays a significant role in applications such as methane (CH4) and carbon dioxide (CO2) storage in geological formations2. During this process, gas molecules adhere to the pore walls of porous materials in reservoirs through physical forces (e.g., van der Waals forces) or chemical interactions (e.g., covalent bonds). Key factors influencing adsorption include pressure, temperature, pore size and structure, gas composition, and the chemical and physical properties of the reservoir rock. At low pressures, monolayer adsorption occurs, while high pressures may lead to multilayer adsorption. Organic-rich rocks like coal and shale exhibit high adsorption capacities for CH4 and CO2, making them crucial for gas storage, unconventional gas production, and greenhouse gas mitigation3,4,5,6,7.

Coalbed methane (CBM) reservoirs and shale formations are recognized as promising candidates for greenhouse gas storage8,9,10. In CBM reservoirs, storage predominantly occurs through adsorption, whereas in shale formations, both adsorbed and free gas phases contribute to their storage capacity. Advanced recovery techniques, such as enhanced CBM recovery (ECBM) and enhanced shale gas recovery (ESGR), utilize CO2 injection to replace CH4, enhancing methane production while simultaneously storing CO2. CBM reservoirs, characterized by their porous structure and high organic content, efficiently adsorb methane (CH4) through physical adsorption onto coal pore surfaces. This process is directly influenced by reservoir pressure, with higher pressures resulting in increased adsorption capacity. Unlike conventional reservoirs, where gas is stored as compressed free gas in void spaces, gas in CBM reservoirs binds to coal surfaces via van der Waals forces, making them ideal for natural gas production and CO2 storage. CO2 injection not only enhances methane production but also contributes to greenhouse gas mitigation11,12,13,14,15,16,17.

In shale formations, gas storage involves a combination of adsorption onto pore surfaces and free gas storage within pore spaces. Shale’s small pore sizes and unique mineral and organic compositions enable strong interactions with CO2, resulting in remarkable adsorption capacities. Factors such as TOC, moisture content, mineral composition, reservoir temperature, and pressure significantly influence adsorption capacity. These properties position shales as a viable option for greenhouse gas storage and unconventional gas production18,19,20,21,22,23.

The adsorption and desorption processes in CBM and shale reservoirs are governed by their porous structures and organic content, which facilitate significant CO2 uptake through strong chemical and physical interactions with the rock matrix. In shale formations, adsorption mechanisms include monolayer and multilayer adsorption, influenced by reservoir pressure. Compared to nonpolar CH4 molecules, CO2 forms stronger bonds with organic functional groups, enabling preferential adsorption24,25,26,27. Parameters such as TOC, mineral composition, and moisture content play critical roles; higher TOC correlates with greater adsorption capacity, while moisture acts as a competing agent, reducing efficiency28,29. Gas storage occurs either as compressed free gas in pore spaces or adsorbed onto pore walls, and these mechanisms are vital for applications like greenhouse gas mitigation, energy storage, and unconventional gas production30,31,32.

Recent advancements in machine learning (ML) have provided robust tools for predicting gas adsorption capacity. Studies have employed algorithms such as artificial neural networks (ANN), least squares support vector machines (LSSVM), and other ML methods to model the adsorption behavior of CO2 and CH4. These models leverage experimental datasets to identify key parameters such as TOC, moisture content, and thermodynamic conditions, achieving superior accuracy compared to traditional isotherm models. The integration of ML techniques offers precise and efficient predictions of gas adsorption behavior under varying reservoir conditions.

In 2024, Tavakolian et al.1 evaluated ML methods for modeling CH4 and CO2 adsorption capacities in tight reservoirs like shale and coal seams, using 3,804 gas adsorption data points with shallow and deep learning models. Their analysis revealed that the Random Forest (RF) algorithm outperformed others, achieving high accuracy in predicting CH4 (MAE = 0.0864, RMSE = 0.1520) and CO2 (MAE = 0.0529, RMSE = 0.2308) adsorption capacities. Sensitivity analysis highlighted the alignment of ML models with geological and reservoir engineering principles, underscoring their potential for laboratory and simulation applications. In 2024, Zhou et al.33 developed a Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) model to predict methane adsorption capacity in shale formations. Using experimental data from the Longmaxi formation in the Sichuan Basin, five key variables—TOC, clay minerals, temperature, pressure, and moisture—were identified as significant. The GPR model outperformed the Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) model, achieving a relative prediction error below 3%. Sensitivity analysis indicated that TOC was the most influential factor, while clay minerals influenced adsorption through interactions with other variables.

In another study, in 2024, Wang et al.34 introduced an innovative approach combining molecular simulation, the lattice Boltzmann method, and ML to predict CO2-CH4 competitive adsorption in large-scale porous shale environments. By training an ANN on molecular simulation data, this method overcame computational limitations and incorporated variables such as shale mineral type and CO2 mole fractions. This approach provides a new foundation for modeling adsorption behavior in porous media, facilitating CO2 sequestration and enhanced CH4 recovery. In 2024, according to the study conducted by Alqahtani et al.35 the objective of this research was to develop a data-driven framework for predicting the adsorption capacity of methane (CH4) and CO2 in unconventional reservoirs such as shale and coal. The study utilized three intelligent models, including General Regression Neural Network (GRNN), Radial Basis Function Neural Network (RBFNN), and CatBoost, which were trained and tested with over 3,800 real data points related to CH4 and CO2 adsorption. To improve model performance, the structure and control parameters of RBFNN and CatBoost were automatically optimized using the Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) method. The results indicated that the CatBoost-GWO combined model provided the most accurate results with RMSE values of 0.1229 and 0.0681 and R2 values of 0.9993 and 0.9970 for CO2 and CH4 adsorption, respectively. Additionally, the model effectively maintained the physical adsorption trends compared to operational parameters and demonstrated superior performance compared to recent ML methods.

In 2023, Alanazi et al.36 proposed an ML framework for predicting CO2 adsorption capacity in coal seams using a dataset of 1,064 experimental data points. Among various ML techniques, RF demonstrated the highest accuracy, particularly for CO2 adsorption at higher pressures. This framework reduces reliance on extensive experiments and complex mathematical models. In 2023, Kalam et al.37 employed Gradient Boosting Regression to predict hydrogen adsorption on kerogen shale for underground storage. This model achieved high accuracy, with a determination coefficient of 99.6% on training data and 94.6% on test data, demonstrating the significance of kerogen type on hydrogen adsorption. This approach significantly reduces the time required for laboratory experiments and molecular simulations.

In 2022, Amar et al.38 utilized Genetic Expression Programming (GEP) to model CH4 adsorption in shale gas formations. Their results revealed that CH4 adsorption is strongly influenced by humidity, pressure, TOC, and temperature. The GEP model exhibited a high correlation coefficient (0.9837), providing user-friendly equations for estimating adsorption capacity. In 2020, Meng et al.39 and Wang et al.40 explored ML models for predicting methane adsorption in shale and gas content in shale reservoirs. Meng et al. evaluated classical isothermal and pressure-temperature integrated models alongside ML methods like ANN, RF, SVM, and XGBoost, with XGBoost showing superior performance by addressing limitations of isothermal conditions and accurately predicting beyond experimental ranges. Similarly, Wang et al. used over 700 data points to compare models such as MLR, SVM, RF, and ANN, identifying RF as the most reliable for predicting Langmuir parameters with high accuracy (R2 = 0.84–0.87). Both studies emphasized the potential of ML for improving accuracy, reducing costs, and optimizing shale gas production and reservoir simulations.

Table 1 summarizes the research background, emphasizing the challenges of predicting gas adsorption in unconventional reservoirs for natural gas and CO2 production and storage. ML methods have emerged as faster, more accurate alternatives to traditional models and costly experiments. Studies show that optimized ML models, such as XGBoost and CatBoost-GWO, achieve high accuracy (R2 > 0.99) and low error rates (RMSE < 0.1), enhancing predictions and enabling large-scale simulations. These models address the limitations of classical methods, reduce computational costs, and support reservoir design, reserve assessment, and gas recovery optimization. ML-based workflows also predict anomalous CO2 adsorption under high-pressure conditions and enable accurate estimation of adsorption capacity based on CO2 injection percentage, rock type, and thermodynamic conditions. The research demonstrates the reliability and practicality of ML techniques in advancing gas adsorption predictions and reservoir management.

Recent advancements in data-driven modeling have significantly enhanced the understanding of complex subsurface phenomena, particularly in tight reservoirs where conventional modeling techniques may fall short. This study presents a novel, data-centric approach to predicting CO2 and CH4 adsorption capacities using a comprehensive experimental dataset under various thermodynamic conditions. By integrating advanced machine learning algorithms. This research not only benchmarks model performance but also reveals critical insights into the governing parameters of gas adsorption. The application of these ensemble learning methods provides a robust framework for capturing nonlinear interactions, thereby offering a more accurate and generalizable prediction of gas behavior in tight formations.

This study investigates the adsorption capacity of methane (CH4) and CO2 in tight reservoirs, specifically shale and coal, utilizing ML techniques. The research focuses on the application of ML algorithms to predict, evaluate, and optimize adsorption data for CH4 and CO2. The dataset was compiled from previous studies conducted by researchers in the field of underground hydrocarbon storage. Given the complexities involved in predicting gas behavior in unconventional reservoirs, this study holds significant importance. Traditional prediction methods, such as mathematical models, numerical simulations, and laboratory measurements, are often constrained by oversimplifications, high costs, and time-intensive processes. Consequently, ML techniques emerge as a promising alternative, offering higher accuracy and reducing computational complexity.

Data collection and specific description

In this study, a dataset comprising 3,804 data points was utilized, originating from the comprehensive experimental compilation presented by Tavakolian et al.1. Specifically, the dataset includes 3,259 data points related to methane adsorption, 390 data points concerning CO₂ adsorption, and 155 data points for the co-adsorption of both gases. These data cover a broad range of thermodynamic conditions and incorporate essential variables such as temperature, pressure, rock type (shale and coal), total organic carbon (TOC), moisture content, and the percentage of CO₂ in the injected gas. This dataset enables a detailed evaluation of the influence of various parameters on gas adsorption capacity and facilitates a thorough understanding of gas behavior in different tight reservoir settings. Further details regarding the dataset and its development can be found in the literature review subsection of the Introduction.

A key aspect of this study was the selection of appropriate input variables for the ML models. These variables were chosen based on scientific analysis and reservoir engineering requirements to effectively reflect the influence of geological and operational factors on gas adsorption capacity. For instance, the percentage of CO2 in the injected gas was identified as one of the most critical variables, given its significant impact on the adsorption process. Additionally, other variables such as TOC and moisture content were incorporated into the modeling process, as each plays a crucial role in determining adsorption capacity.

To prepare the dataset for this study, raw data were collected from various sources, organized, and analyzed using Microsoft Excel. These data included variables such as pressure, temperature, rock type, and the composition of injected gases. The processed data were subsequently utilized as inputs for ML modeling techniques. To optimize the models, methods such as linear regression were employed, and the validity of the data was assessed and confirmed using the coefficient of determination (R2). The results of these analyses demonstrated a strong correlation between the input and output variables of the models. ML models for predicting gas adsorption capacity in reservoirs were developed based on the following relationships:

Equations (1) and (2) enabled researchers to accurately predict the effects of various parameters on gas adsorption capacity. Additionally, the models demonstrated the capability to forecast anomalous gas behaviors under high-pressure conditions. The findings of this study revealed that the proposed ML models, utilizing optimized input variables, are capable of accurately predicting gas adsorption capacities. Sensitivity analysis of the models further confirmed that parameters such as TOC and the CO2 fraction in the injected gas have the most significant impact on adsorption capacity. This research, by introducing innovative approaches for data analysis, provides a solid foundation for applying ML models in gas storage processes within unconventional reservoirs. Further details and statistical information related to this study are presented in Table 2.

The provided table contains various statistical details of data related to the excess adsorption of CO2 and CH4 gases, rock properties (such as TOC and moisture content), pressure, and temperature. Statistically, most of the data for parameters such as CO2 percentage, rock type, moisture content, and excess CO2 adsorption are concentrated at lower values, with their mode and median being zero, and their distribution showing a significant skew toward lower values (positive skewness). In contrast, parameters like TOC and excess CH4 adsorption exhibit distributions with moderate to high positive skewness, indicating a concentration of data at lower values. However, their maximum values are significantly higher than the mean and median, suggesting the presence of outliers or extreme values in the dataset.

On the other hand, parameters such as temperature and pressure have more balanced distributions, with their skewness generally being positive but low. Specifically, temperature, with a median of 50.4 °C and a mean of 57 °C, indicates a relatively uniform distribution across the temperature range. Overall, most of the data for rock properties and gases are concentrated at lower ranges, while higher values appear more scattered with distributions exhibiting high kurtosis (sharpness and peakedness), likely due to the presence of unusual data points or outliers. These results emphasize the importance of paying attention to outliers and extreme values in future analyses, particularly in the development of predictive and ML models.

After data collection, the data were examined and, from a statistical perspective, the CO2 and CH4 adsorption capacity was plotted as a function of temperature, pressure, rock type (shale and coal), TOC, moisture content, and the percentage of CO2 in the injected gas. In these analyses, violin plots, pair plots, and heat maps were presented.

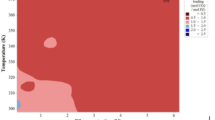

In this study, a dataset comprising various features was collected and analyzed to investigate the characteristics of CO2 storage and gas behavior in different environments. Initially, violin plots (Fig. 1) were used to fully display the data distribution across various dimensions. These plots are particularly effective in showing the composition and scatter of the data, which is especially useful for analyzing complex and nonlinear data. Moreover, these plots specifically illustrate how the data are distributed across different levels for each feature. For instance, in the CO2 percentage plot, the data distribution is predominantly in the lower ranges, indicating the absence of high CO2 values in most samples; however, the spread of data towards higher values indicates variation among the samples. Similarly, the TOC distribution is mainly concentrated below 5%, which could be attributed to natural variations in rock composition and storage environments. Additionally, the moisture distribution has a broader range and greater scatter, reflecting significant differences in the moisture content of the samples. High variability is also observed in the temperature and pressure plots. Specifically, temperature spans from approximately 20 °C to 160 °C, allowing for the prediction of its effect on gas behavior and hydrogen storage characteristics. Pressure is primarily concentrated above 10 megapascals, indicating typical high-pressure gas storage conditions. Furthermore, CH4 and CO2 adsorption values are generally low, which may indicate storage environments with low adsorption of these gases. Overall, these plots provide a comprehensive picture of gas storage conditions and rock properties, serving as valuable tools for modeling analyses and engineering predictions in gas storage applications.

The paired plots in Fig. 2 illustrate the complex relationships between various parameters and the CO2 and CH4 adsorption capacities. Each individual plot analyzes the interaction between two specific variables and provides insights into their correlations and general trends in the data. One notable observation is seen in the plots showing the relationship between CO2 adsorption and pressure. As pressure increases, CO2 adsorption steadily increases, highlighting the significant impact of pressure on gas adsorption capacity in shale samples. This positive correlation suggests that higher pressures enhance the shale’s ability to adsorb CO2 through its pore network or adsorption mechanisms.

In contrast, the plots depicting the relationship between CH4 adsorption and pressure exhibit an inverse pattern. As pressure increases, CH4 adsorption decreases significantly, indicating an inverse relationship between pressure and methane adsorption. This observation suggests that higher pressures may disrupt the shale’s ability to retain CH4 molecules, likely due to competitive adsorption or changes in gas behavior under pressure.

Furthermore, the plots examining the relationship between CO2 adsorption and other variables, such as TOC, maturity, and temperature, show no significant trends or patterns. This lack of clear correlations suggests that these factors may not have a direct impact on the CO2 adsorption capacity of shale samples within the studied range. Similarly, the plots analyzing the relationship between CH4 adsorption and TOC, maturity, and temperature also show no discernible trends, indicating that these factors do not play a dominant role in determining methane adsorption capacity in shale samples.

Numerical correlation matrices are essential tools in ML and data analysis. These matrices represent the linear relationships between different variables and can be valuable in various processes such as feature selection, dimensionality reduction, and exploratory data analysis (EDA). In this study, the Pearson correlation coefficient is used to compute the thermal numerical correlation matrix shown in Fig. 3. The Pearson correlation coefficient is a statistical measure that quantifies the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two variables. It is represented by a value between − 1 and 1.

Pearson correlation coefficient values can be positive, negative, or zero (indicating no correlation). A perfect positive correlation means that as the value of one variable increases, the other variable increases in proportion. A perfect negative correlation means that as the value of one variable increases, the other variable decreases in proportion. No correlation indicates that there is no linear relationship between the two variables.

According to Eq. 3, the Pearson correlation coefficient is expressed as follows:

In this equation, \(\:{X}_{i}\) and \(\:{Y}_{i}\) represent the observed values, and \(\:\stackrel{-}{X}\) and \(\:\stackrel{-}{Y}\) are the mean values of variables \(\:X\) and \(\:Y\), respectively. Therefore, if \(\:r>0\), a positive (direct) correlation exists, and it should be noted that the closer the value of r is to 1, the stronger the positive relationship. Similarly, if \(\:r<0\), a negative (inverse) correlation exists, and it should be noted that the closer the value of r is to −1, the stronger the negative relationship. It is important to note that if \(\:r=0\), no linear relationship exists, and the relationship may be nonlinear (in which case, no correlation is present).

In this study, the Pearson correlation coefficient and heatmap were employed to assess the relationships between various variables, such as temperature, pressure, rock type (shale and coal), TOC, moisture content, and the percentage of CO2 in the injected gas. This information can aid in process optimization and more effective decision-making.

The heatmap provides a comprehensive representation of the Pearson correlation coefficients between different parameters and the CO2 and CH4 adsorption capacities in shale samples. The intensity and color direction (red for positive correlation, blue for negative correlation) indicate the strength and direction of the linear relationship between each pair of variables.

One prominent trend observed in the heatmap is the strong positive correlation between CO2 percentage and CO2 adsorption capacity (0.58), suggesting that as the CO2 content in the shale gas mixture increases, the shale’s capacity to adsorb CO2 also rises. This relationship indicates that CO2 adsorption in shale is influenced by the partial pressure of CO2 in the gas phase, with higher CO2 concentrations leading to increased adsorption. Conversely, a notable negative correlation between CH4 adsorption and CO2 adsorption (−0.16) suggests that the presence of CO2 may interfere with CH4 adsorption. This negative correlation could be due to competitive adsorption between CO2 and CH4 molecules for the same adsorption sites in the shale matrix.

Interestingly, the heatmap also reveals a strong positive correlation between CO2 percentage and TOC content (0.61), as well as between TOC and CO2 adsorption capacity (0.34). These correlations suggest that TOC plays a significant role in influencing CO2 adsorption in shale, possibly by providing additional adsorption sites or enhancing the overall adsorption capacity of the shale through its intrinsic physicochemical properties. In contrast, CH4 adsorption shows a weak correlation with TOC (−0.10), indicating that TOC content may not be a major factor in influencing CH4 adsorption.

Additionally, the heatmap indicates a positive correlation between pressure and CO2 adsorption (0.18), suggesting that higher pressures facilitate CO2 adsorption. However, the correlation between pressure and CH4 adsorption is negative (−0.17), implying that higher pressure may hinder CH4 adsorption. These opposing trends highlight the different behaviors of CO2 and CH4 under varying pressure conditions in the shale environment.

Furthermore, the heatmap shows a negative correlation between temperature and CO2 adsorption (−0.11) and a positive correlation between temperature and CH4 adsorption (0.26). This suggests that temperature may affect the adsorption behavior of both gases, possibly through its effects on gas kinetics and the shale matrix’s characteristics.

Machine learning model

In similar problems, ML models, particularly regression models, are utilized. These models help us better understand how changes in independent variables influence the dependent variable and how a relationship is established between them. Various learning methods are employed to define this relationship. In this study, five common methods that yield satisfactory results in such problems have been used. These methods include RF, CatBoost, AdaBoost, and ExtraTrees. Each of these methods is explained in detail below.

Random forest

Due to its non-parametric nature and ability to efficiently handle large datasets, the RF algorithm can achieve high performance in studies of this type. RF is an ensemble model of decision trees (DTs), with each DT constructed using the Classification and Regression Trees (CART) method41. By utilizing a random subset of the training data and random features at each split, RF reduces variance and provides better generalization42. This algorithm combines the interpretability of DT with the robustness of ensemble learning, resulting in higher predictive power and a reduced risk of overfitting. Random Forest Regression (RFR) is an advanced version of the Decision Tree Regression (DTR) algorithm, leveraging these advantages to enhance performance43. A flowchart of this model is shown in Fig. 4.

In this study, RF was implemented using the Scikit-learn library in Python and relied on the Bootstrap Aggregation (Bagging) method to independently construct DTs, which reduces the variance errors associated with individual models44. The final regression prediction is obtained by averaging all the predicted values from each tree, thereby enhancing the accuracy and robustness of the model45. The RFR algorithm performed several key steps46:

-

1)

Bootstrap Sampling: The training set was sampled k times using the bootstrap method, creating k subsets of the training data with equal sizes.

-

2)

Feature Selection and Tree Construction: For data with M features, a random subset of m (M > m) features was selected from all M features to be used as candidate feature subsets for a node. The feature impurity index was then used to identify the best node and branch, and k DTR models were constructed.

-

3)

Final Prediction: The average of the k predictions was calculated to provide the final regression result.

Categorical boosting

Advanced ML algorithms, such as CatBoost, have been developed to address the limitations of individual models. CatBoost is a member of the Gradient-Boosted Decision Trees (GBDT) family and is primarily recognized for its exceptional capabilities in processing categorical features. One of the key features of CatBoost is that it does not require extensive preprocessing of categorical data, which is often a time-consuming task in other gradient boosting frameworks. CatBoost operates differently; it utilizes advanced methods such as Ordered Boosting and Target Encoding to handle overfitting (Fig. 5)47,48,49.

Compared to other gradient boosting techniques that typically require categorical variables to be converted into numerical data, CatBoost can directly handle categorical features, significantly reducing the amount of preprocessing needed. By processing categorical data directly, CatBoost can leverage key information more effectively, making the model more efficient. As part of the GBDT framework, CatBoost constructs a series of DTs sequentially, with each tree aiming to capture the residual errors of the previous trees. Weights are adjusted based on the prediction errors of the training samples, adapting the model to more challenging samples.

CatBoost also employs unique strategies for performance optimization. For example, Ordered Boosting, where trees are ordered based on combinations of a feature rather than random or sequential orders, improves the model’s accuracy by focusing on more informative features. Additionally, CatBoost uses Oblivious Trees50,51, which allow for parallel computation during the training process, resulting in time savings and improved performance. Finally, CatBoost organizes the training samples in a fixed order and gradually increases the number of training samples for each model. This systematic and gradual learning process offers advantages over building a model at each iteration, as it helps progressively improve performance52.

Adaptive boosting

As shown in Fig. 6, Boosting is a ML technique used to combine multiple weak models, such that the resulting model has better predictive accuracy than any individual model. AdaBoost, one of the most well-known types of boosting, is a sequential ensemble learning method that gradually improves model performance by correcting the weights of misclassified data points in previous models53,54,55.

In this algorithm, a weak learner, often a DT, is first trained on the original dataset. In each iteration, the algorithm adjusts the weights of the training data and places more emphasis on the data points that were misclassified in previous iterations. This process is cyclical, with predictions being continuously improved, and each subsequent model leading to a more accurate result.

At each stage, AdaBoost increases the weight of misclassified samples to ensure that the next weak learner focuses more on them. Ultimately, all the weak learners are combined, and the final model is created, with each learner being weighted according to its performance.

One important aspect of AdaBoost is its ability to combine weak learners, which can be applied with techniques such as Support Vector Regression (SVR) or DTR. AdaBoost has proven to perform well in both classification and regression tasks and typically outperforms other ensemble methods in terms of accuracy.

However, this algorithm is not without limitations. Some weaknesses of AdaBoost include its sensitivity to outliers and noisy data, as incorrect samples receive higher weights. Additionally, due to the number of iterations required for training, the algorithm is computationally expensive and may lead to overfitting if the weak learners are too complex or the dataset is too small56,57,58.

Extra trees regressor

Extra Trees Regressor (ETR) is an ensemble learning method that operates by creating a large number of DTs independently. In this method, at each node, a feature and the branching value are selected randomly59,60. Similar to the RF algorithm, which is also based on an ensemble of DTs, ETR differs in its training and branching approach. Specifically, RF uses bootstrap sampling (randomly creating subsets of data with replacement) and finds the best branches using criteria such as Gini impurity or mean squared error (MSE). In contrast, the ETR algorithm is trained on the entire dataset and selects features and branching values randomly at each node. This additional randomness in the branching phase often results in better performance for ETR, especially when overfitting is a concern61.

To separate the nodes, ETR randomly selects binary branching values, while RF determines a set of candidates branching values for each feature and selects the best one based on optimization criteria. Additionally, ETR uses the entire original dataset as training data (to construct leaf nodes), whereas RF uses bootstrap sampling to create subsets of data. The simpler node branching method in ETR makes it computationally more efficient than other ensemble methods. The higher randomness in ETR reduces the overfitting problem, while the use of the entire dataset minimizes bias and improves the model’s performance for new data.

To enhance performance, several hyperparameters are tuned for both RF and ETR. These hyperparameters include the number of trees, the maximum depth of each tree, the number of features considered at each branching, the minimum number of samples required for branching, and the minimum number of samples required to split leaf nodes62. Adjusting these hyperparameters allows for balancing bias and variance, thereby improving the model’s prediction performance (Fig. 7).

Machine learning methods modeling process

The modeling process using ML algorithms involves a series of structured steps, progressing from data preparation to model evaluation and optimization. The first step is data collection and preprocessing. In this stage, the data must be examined for quality and suitability for the problem at hand. Subsequently, actions such as removing outliers, filling in missing values, and standardizing the data to create a uniform scale are performed. The use of algorithms like CatBoost, which can directly process categorical data, reduces the complexity of this stage.

Next, key feature selection and engineering are carried out, as these features directly influence the model’s performance. In this step, tools such as correlation analysis and dimensionality reduction methods, like Principal Component Analysis (PCA), are used to identify and select the most impactful features. This process helps reduce data complexity and increases processing speed. Once the data is prepared, the appropriate algorithm for modeling is chosen. The selection of the algorithm depends on the type of data and the model’s objective. Algorithms like RF, ETR, and CatBoost, due to their various capabilities, are suitable options for diverse problems.

Fine-tuning hyperparameters, such as the number of trees and their depth, through methods like grid search or random search, ensures improved model accuracy and establishes a balance between bias and variance. After model tuning, training begins using the training data, and performance is evaluated using validation data. Techniques like cross-validation help mitigate overfitting and ensure the model’s performance on new data. Models like AdaBoost, which focus on difficult samples and correct errors at each stage, yield better prediction results.

In the final stage, models are evaluated and compared using metrics such as MSE, MAE, and the Coefficient of Determination (R2). Algorithms like ETR, which utilize randomization in the branching process and employ the entire dataset, and CatBoost, with its ability to directly handle categorical data, have shown successful performance in many complex problems. These steps aid in selecting the optimal model and significantly increase prediction accuracy.

Results and discussion

As stated in the data collection section, this study was conducted to investigate the CO2 and CH4 adsorption capacities in tight reservoirs using available experimental data and ML techniques. The dataset comprises 3,804 samples of measured parameters, including temperature, pressure, rock type (shale and coal), TOC, moisture content, and the percentage of CO2 in the injected gas. These data were statistically evaluated, and the results were analyzed using graphical charts such as violin plots, pair plots, and heat maps, which illustrate the dispersion, continuity, and correlation among variables. Furthermore, the statistical findings related to the data are presented in Table 3.

The dataset used in this study is divided into two sections: CO2 and CH4 adsorption data. Each section was analyzed separately and then compared. Both sections were further divided into two subsets: a training set containing 70% of the data and a testing set comprising the remaining 30%. The training dataset was utilized to develop the most optimal model and select relevant features. During this stage, the model learned to establish relationships between the input parameters and approximate the target values to the actual or measured values.

During training, the model adjusted its parameters (such as weights in neural networks) to minimize prediction errors, enabling it to make accurate predictions based on the training data. The testing dataset, which accounted for 30% of the total data, was used to evaluate the predictive capability and performance of the trained model. After training, the model’s performance was assessed using the test data without further adjustments to its parameters. This approach demonstrated that the model effectively avoided overfitting on the training data while achieving acceptable performance.

The model performed consistently well on both the training and testing datasets, producing satisfactory results and validating its performance. This indicates that the model is robust and likely to perform well in real-world scenarios.

Hyperparameter optimization

This study addresses the challenge of parameter tuning in ML algorithms and proposes Bayesian optimization as an effective solution to this problem. ML algorithms often require the adjustment of parameters to control the learning rate and model capacity, which can be considered a nuisance. While one approach is to minimize the need for these parameters, another approach is to automate their optimization. Bayesian optimization is recommended as an efficient method for this purpose, as it has demonstrated superior performance compared to other global optimization techniques.

This method operates under the assumption that the unknown function (in this case, the performance of a learning algorithm with various parameter settings) is sampled from a Gaussian process, which maintains a posterior distribution. The optimization process involves selecting parameters for subsequent evaluations based on criteria such as the expected improvement (EI) or the upper confidence bound (UCB) derived from the Gaussian process. Studies have shown that EI and UCB are highly effective in identifying global optima for many black-box functions63,64,65,66.

The distinctive characteristics of ML algorithms in optimization are further elaborated in this study. To evaluate each function, the time variations caused by differences in model complexity are analyzed, along with the economic implications of performing experiments on cloud computing platforms. According to the study by Snoek and Larochelle67, Bayesian optimization algorithms have demonstrated favorable results in ML applications.

This research also advocates for a fully Bayesian treatment of the Gaussian process kernel, rather than merely optimizing its hyperparameters. Furthermore, the aforementioned study introduces new algorithms designed to account for variable experimental costs or the simultaneous execution of experiments. Gaussian processes are highlighted as effective alternative models in such scenarios.

In this study, the selection of hyperparameters played a critical role in enhancing the performance and accuracy of models used for analyzing laboratory data. Table 4 presents the optimal hyperparameter settings for four different models— RF, CatBoost, Extra Trees, and AdaBoost—applied to the adsorption of CO2 and CH4 gases. These settings were determined using the Bayesian optimization method.

For the CO2-related data, the optimal hyperparameters were determined as follows:

-

Random Forest: The maximum tree depth is set to 101, and the minimum number of samples per leaf is 1, enabling the model to capture more complex patterns. The minimum number of samples for splitting nodes is 2, and the total number of trees is 618, enhancing both accuracy and robustness.

-

CatBoost: The tree depth is 8, with an L2 regularizer value of 2.8601 for the leaves. A learning rate of 0.155 ensures a balance between convergence speed and model accuracy.

-

Extra Trees: The model is configured with a maximum tree depth of 14 and 62 trees, optimizing computational efficiency while maintaining performance.

-

AdaBoost: With a high learning rate of 0.9855, a tree depth of 9, and 140 learners, the model achieves faster convergence and reliable results.

For the methane-related data, the hyperparameter settings were adjusted to manage complexity and improve predictive performance:

-

Random Forest: A maximum tree depth of 179 captures finer details in the data, while 149 trees contribute to enhanced accuracy.

-

CatBoost: The tree depth is 8, with an L2 regularizer value of 2.4742. A learning rate of 0.1857 ensures an optimal trade-off between accuracy and convergence speed.

-

Extra Trees: To uncover more intricate patterns, the model is designed with a maximum tree depth of 20 and 258 trees.

-

AdaBoost: A learning rate of 1, combined with a tree depth of 10 and 57 learners, results in fast convergence and effective performance in analyzing methane data.

The careful selection of hyperparameters for these models— RF, CatBoost, Extra Trees, and AdaBoost—has significantly enhanced their accuracy and robustness in analyzing laboratory data for CO2 and methane. The tailored combination of settings, such as tree depth, learning rate, and the number of trees, has allowed each model to operate optimally based on the specific characteristics of the dataset. These configurations strike a precise balance between capturing complex patterns, achieving convergence speed, and minimizing overfitting, ultimately leading to improved data evaluation and more accurate analysis in related studies.

Evaluation and model performance

Error metrics

Evaluation metrics play a vital role in assessing the performance of ML models. They provide a means to measure, analyze, and improve the models’ accuracy and operational capabilities. Selecting the appropriate evaluation metrics is crucial, as decisions based on these metrics can significantly influence the quality and performance of ML models. Hence, careful consideration of the evaluation metrics for each specific ML task or project is essential.

One of the most widely used evaluation metrics is the coefficient of determination (R2), which quantifies how much of the variance in the dependent variable is explained by the model. A higher R2 value indicates a stronger fit between the model and the data, with a value of 1 representing a perfect fit and 0 indicating no explanatory power (Eq. 4). This metric is particularly effective in illustrating the degree of difference between the actual and predicted values of the model.

Another key metric used in this study is the RMSE, which measures the square root of the mean squared difference between the actual and predicted values (Eq. 5). RMSE is highly sensitive to outliers and provides insights into the model’s overall prediction accuracy, with lower values indicating greater precision.

The MAE is also utilized to evaluate model performance. MAE calculates the average absolute difference between actual and predicted values, providing a straightforward interpretation of prediction errors in the same unit as the target variable (Eq. 6). Like RMSE, a lower MAE value reflects better model performance.

Additionally, the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) is used as a performance metric to measure prediction accuracy in percentage terms. It is computed by dividing the absolute difference between predicted and actual values by the actual values and multiplying the result by 100. MAPE is particularly valued for its simplicity and interpretability, with lower values signifying higher accuracy. However, MAPE has limitations when applied to datasets containing values close to zero, as the percentage error can become exaggerated.

In conclusion, selecting and employing the right evaluation metrics, such as R2, RMSE, MAE, and MAPE, is integral to understanding and improving ML models’ performance. Each metric provides unique insights into the model’s accuracy and operational effectiveness, making them essential tools in developing reliable ML solutions.

These equations (4 to 7) contain values presented in Table 5. The values obtained from the calculations and the associated errors in the data are provided in Table 6. Subsequently, the predictive capability of the model, along with a discussion of the results presented graphically, is evaluated.

For model evaluation, various error metrics, including the coefficient of determination, RMSE, MAE, and MAPE, were calculated for both the test data and the entire dataset. The results are shown in Table 6.

By evaluating the error metrics, it can be observed that the performance of all four developed models for both CO2 and CH4 adsorption is very good and similar to each other. Since the performance on the test data did not show a significant decline compared to the training data in all the constructed models, it can be concluded that overfitting did not occur. The CatBoost and Extra Trees models performed better than the other models across all error metrics. The correlation coefficient and RMSE for the CatBoost model, for both gases and across all data, are better than those of Extra Trees. However, the MAE and MAPE values for the total data are more favorable in the Extra Trees model compared to CatBoost. It should be noted that although Extra Trees exhibited better performance than CatBoost in the training dataset for both gases, it also showed a more significant decline in the test dataset. Therefore, although Extra Trees performed better in terms of MAE and MAPE error metrics, it has lower generalizability compared to the CatBoost model overall.

Graphical methods

To gain a better understanding of the models’ performance, cross plots can be utilized. In this method, the model outputs are plotted against the actual values. The closer the points are to the line with a slope of one and an intercept of zero, the better the model’s performance. The performance of the models related to CH4 adsorption is shown in Fig. 8, where the superior performance of the CatBoost and Extra Trees models is evident. As expected from the error metrics, AdaBoost exhibited the worst performance, with many points showing significant deviations from the actual values. The RF model demonstrated relatively good accuracy, but there was still noticeable data dispersion compared to the ideal line. Although the Extra Trees model performed better than CatBoost in the MAE and MAPE error metrics, it is evident from the cross plot that the CatBoost model demonstrated much better performance, with the data points well aligned along the ideal line.

The cross plot for the CO2 models is also shown in Fig. 9. Here, the performance of the two models, AdaBoost and RF, is weaker compared to the other models. As with the CH4 models, despite Extra Trees performing better than CatBoost in the MAE and MAPE error metrics, the cross plots show the superior performance of CatBoost compared to Extra Trees.

To closely examine the model performance, the cumulative frequency chart for the absolute error of each model is shown in Fig. 10. In this approach, the higher the chart for a model, the better its performance. Figure 10 A corresponds to the models built for CH4. Based on this, the Extra Trees model outperforms the others noticeably up to an absolute error of 0.14, but after that, the CatBoost model performs better. These two models estimated 94.2% of the data with an error of less than 0.14, indicating their exceptional performance. The RF and AdaBoost models show similar performance, with RF outperforming up to an error of 0.17. However, after that, AdaBoost improves and shows better performance.

To enhance the transparency and reproducibility of this study, the training/testing datasets and output results associated with the CatBoost model—used for evaluating CO2 and CH4 adsorption—have been provided as supplementary materials accompanying this manuscript.

The cumulative frequency chart for CO2 also shows similar results to CH4 (Fig. 10B). However, in this case, the superior performance of the CatBoost and Extra Trees models compared to RF and AdaBoost is clearly noticeable, with a significant gap between the charts. Both Extra Trees and CatBoost models estimated 80% of the data with an absolute error of less than 0.13. Additionally, the CatBoost model estimated over 90% of the data with an absolute error of less than 0.22, while this value for the Extra Trees model reaches 0.27. The results of this section indicate that, despite the better performance of Extra Trees compared to CatBoost in terms of MAE and MAPE, both models are highly competitive, with CatBoost showing superior performance in some cases.

Outlier detection

To identify outliers and the applicable range of the model within a dataset, a well-known graphical method called the Williams plot was used. Utilizing the Williams plot and identifying outliers in this chart can assist in evaluating the reliability of the resulting model. In fact, a high percentage of outliers can disrupt the model’s performance and ultimately render it unreliable. In other words, the significant presence of outliers can lead the model to focus unduly on data points that are statistically invalid, thus compromising its overall performance. Therefore, the examination and identification of outliers is a critical step in modeling.

This technique relies on the Hat matrix (H) and the calculation of standardized residuals (SR). The Hat matrix is used to calculate the predicted values of the response variable, while the standardized residual is the residual divided by its estimated standard error. The matrix MX has dimensions of n × p, where n and p represent the number of data points and input variables, respectively, and SD is the standard deviation.

Leverage points, which are data points that have a significant effect on the regression coefficients of the model, can be identified using the Hat matrix. The diagonal elements of the Hat matrix are examined to identify these leverage points. Data points with a value greater than the leverage warning value (Hat*) = 3(p + 1)/n are considered high-leverage points.

The safe ranges for statistical validation of both the developed models and the dataset are 0 ≤ H ≤ H* and − 3 ≤ SR ≤ 3. If data points do not match the defined ranges, they can be categorized into three possible groups:

-

1)

Suspicious vertical data: This includes data points that fall outside the ranges Hat* ≥ H and SR > 3 or SR < −3, and are outside the applicable range.

-

2)

Good leverage data: This includes data points that fall within the ranges Hat* < H and − 3 ≤ SR ≤ 3.

-

3)

Bad leverage data: This includes data points that fall within the ranges H > Hat* and SR > 3 or SR < −3.

As shown in Fig. 11, the first chart (A) examines the data related to CH4 adsorption using the Hat matrix. The horizontal axis represents the Hat values, while the vertical axis indicates the SR. Blue points are identified as valid data and fall within the red line (leverage threshold). Yellow points, which are near the suspicious range, are identified as suspicious data. In this chart, a significant number of data points lie within the suspicious range or outside of leverage (red points), indicating the potential presence of outliers or points with a significant impact on the model.

Leverage thresholds of 0.005, 0.01, and 0.015 are set to help identify high-risk data points. This analysis highlights the importance of monitoring the data to ensure modeling accuracy. In the second chart (B), valid data are marked with blue points, while suspicious data are marked with yellow points. The proportion of suspicious data is lower compared to the CH4 chart, indicating more stable data for CO2 in modeling.

The Hat values are divided into ranges of 0.01, 0.02, 0.03, 0.04, and 0.05, which are used for a more detailed analysis of the impact of different data points on the modeling. Overall, this chart shows that CO2 data has less impact outside the leverage threshold, and the model potentially performs better in this region. These analyses emphasize the impact of outliers in the modeling of CH4 and CO2 adsorption in reservoirs and highlight the need for careful data examination to improve model accuracy.

Using a leverage threshold of 0.0062 and |SR| > 3, the CH₄ dataset contained outliers that exhibited significant deviations in multiple input features. A statistical comparison revealed that:

Results in Table 7 indicate that the outliers are characterized by extremely high TOC and elevated moisture content, suggesting that they may reflect valid but rare geological formations (e.g., highly organic-rich, water-retentive shales). These points could also stress the limitations of the model in high-TOC, high-moisture regions.

For the CO2 dataset, with a leverage threshold of 0.0385 and |SR| > 3, the outliers were found to differ primarily in terms of TOC only. The statistical summary is shown below:

Based on Table 8, Unlike CH4, CO2 outliers are not high in moisture; in fact, they have significantly lower moisture content than the average. This suggests that the model underperforms in low-moisture and high-TOC conditions, which are geologically plausible scenarios such as dry, highly mature shales. These outliers do not show high leverage and are unlikely to distort the model structurally, indicating they are likely true but difficult-to-predict samples rather than data errors.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis is one of the key steps in improving model performance and interpreting the results in the prediction of CO2 and CH4 gas adsorption. This method helps identify the impact of input variables on the model’s outcomes and indicates which parameters have the greatest influence on model performance. In this study, sensitivity analysis was performed using ML algorithms such as CatBoost and Extra Trees, based on the SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) technique (Fig. 12).

The use of the SHAP technique allows for the examination of the contribution of each input variable to the model’s output. This technique not only reveals the impact of variables at different levels but also uncovers the nonlinear relationships and interactions between parameters. The SHAP analysis demonstrated that the pressure variable had the greatest contribution to the prediction of gas adsorption capacity at all stages of modeling, while the temperature variable only had a significant impact at high values.

According to the SHAP chart for CH4 gas, the pressure variable and the percentage of TOC are the most influential factors on CH4 adsorption. An increase in pressure significantly enhances CH4 adsorption capacity, as indicated by a high positive SHAP value. The percentage of TOC also shows a similar positive influence, reflecting the importance of the organic content of the reservoir rock in improving CH4 storage. In contrast, temperature has a negative impact on CH4 adsorption. Higher temperatures result in a reduced storage capacity, which is observed in the lower SHAP values at higher temperatures. This can be attributed to the decreased tendency of CH4 molecules to adsorb on the rock surface at higher temperatures. Other variables, such as rock type and moisture, also have limited but significant impacts on CH4 adsorption. Rock type, due to its porosity and structural characteristics, may enhance adsorption, while increased moisture negatively affects CH4 adsorption, resulting in a reduced SHAP value.

For CO2 gas, pressure remains the most influential variable. Increased pressure leads to a significant rise in the SHAP value, indicating an increased CO2 adsorption capacity at higher pressures. Additionally, the percentage of CO2 in the gas mixture has a positive and significant impact, with higher values of this variable improving CO2 adsorption. Temperature, like for CH4, has a negative effect on CO2 adsorption. The negative impact of temperature on CO2 is more pronounced than for CH4, and the decrease in adsorption capacity with rising temperature is clearly visible in the SHAP chart. This result may be due to the higher volatility of CO2 at elevated temperatures. Variables such as rock type and moisture play secondary roles in CO2 adsorption. Although their impact is limited, rock type, due to its surface characteristics and porosity, and moisture, due to occupying pore space, can influence the final results. This sensitivity analysis for CO2 provides valuable insights for the design and optimization of storage systems.

In general, sensitivity analysis is an effective tool for gaining a deeper understanding of the impact of various variables on gas adsorption. This method not only aids in improving modeling accuracy but also provides useful information for designing future experiments and optimizing operational conditions in gas adsorption systems.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the significant potential of ML models in enhancing the understanding of CO2 and CH4 adsorption capacities in tight reservoirs, utilizing data from prior research. By integrating ML techniques with laboratory data, the research provides valuable insights into optimizing gas injection and storage processes. The evaluation of 3,804 data points, covering variables such as temperature, pressure, rock type, TOC, and gas composition, revealed that different parameters exert varying effects on adsorption capacity.

This study underscores the value of data-driven modeling for adsorption analysis in tight reservoirs by utilizing a diverse and extensive dataset in conjunction with state-of-the-art machine learning techniques. Among the evaluated algorithms, ensemble-based models such as Random Forest, CatBoost, AdaBoost, and Extra Trees demonstrated superior predictive capability and interpretability. These results highlight the importance of employing advanced ML tools to uncover complex patterns in experimental data, ultimately improving our understanding of gas-rock interactions under varying thermodynamic conditions. The findings contribute to the development of more accurate predictive tools for gas storage and enhanced recovery strategies in unconventional reservoirs.

The study found that CO2 percentage in injected gas and TOC are pivotal factors influencing CO2 adsorption, with TOC positively impacting CO2 adsorption by providing microporous sites. Pressure also plays a critical role, enhancing CO2 adsorption while inversely affecting CH4 adsorption due to competitive interactions. Temperature had a negative impact on CO2 adsorption but slightly increased CH4 adsorption, suggesting gas-specific interactions with rock properties. Correlation analysis further confirmed the competition between CO2 and CH4 for adsorption sites, with TOC and CO2 concentration demonstrating the strongest positive effects on CO2 adsorption.

ML models, particularly CatBoost and Extra Trees, proved highly effective in predicting gas adsorption, achieving high R2 values (0.9989 for CO2 and 0.9965 for CH4) and low prediction errors (RMSE and MAE). The CatBoost model demonstrated superior overall performance, with strong stability and accuracy across all metrics. The sensitivity analysis revealed that pressure is the most influential factor, followed by TOC and CO2 percentage, while temperature acted as a restrictive variable. Secondary variables such as rock type and moisture content, though less impactful, were also highlighted.

The results underline the importance of careful hyperparameter tuning and the application of advanced ML techniques to improve model performance and optimize gas storage systems. This research provides a robust framework for future studies on gas adsorption in diverse reservoir conditions, emphasizing the utility of combining laboratory data with ML methods. The findings offer practical guidance for managing gas injection processes and improving storage capacity in tight reservoirs.

Challenges ahead

-

Generalizability of Results

Although the CatBoost model has demonstrated significant performance, the generalization of these models to other reservoir conditions and unseen data still requires further investigation. Particularly, the behavior of gases may differ across various reservoirs or under different operational conditions.

-

Use of Advanced and Interpretable Models

The use of more advanced methods and models can significantly contribute to modern research fields. While ML techniques were utilized in this study, other methods such as deep learning or interpretable models like Genetic Programming (GP), GEP, and Group Method of Data Handling (GMDH) could be considered for future research.

-

Recommendations

Future studies could explore several capabilities and potentials to expand the scope of this research, making it more comprehensive and detailed, and thus more accessible to both the scientific and industrial communities. Among these considerations are the use of more extensive datasets, the application of novel ML techniques, and the integration of deep learning models. Additionally, the use of other gas mixtures, such as cushion gas, could be explored, particularly in reservoirs with different rock types and thermodynamic conditions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural networks

- CART:

-

Classification and regression trees

- CBM:

-

Coalbed methane

- CO2 :

-

Carbon dioxide

- DT:

-

Decision tree

- DTR:

-

Decision tree regression

- EI:

-

Expected improvement

- ESGR:

-

Enhanced shale gas recovery

- ETR:

-

Extra trees regressor

- GBDT:

-

Gradient-boosted decision tree

- GEP:

-

Genetic expression programming

- GMDH:

-

Group method of data handling

- GP:

-

Genetic programming

- GPR:

-

Gaussian process regression

- GRNN:

-

General regression neural network

- GWO:

-

Grey wolf optimization

- H:

-

Hat

- LSSVM:

-

Least squares support vector machines

- MAE:

-

Mean absolute error

- MAPE:

-

Mean absolute percentage error

- ML:

-

Machine learning

- MSE:

-

Mean squared error

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- RBFNN:

-

Radial basis function neural network

- RF:

-

Random forest

- RMSE:

-

Root mean square error

- SR:

-

Standardized residuals

- SVR:

-

Support vector regression

- TOC:

-

Total organic carbon

- UCB:

-

Upper confidence bound

- XGBoost:

-

Extreme gradient boosting

References

Tavakolian, M., Najafi-Silab, R., Chen, N. & Kantzas, A. Modeling of methane and carbon dioxide sorption capacity in tight reservoirs using Machine learning techniques. Fuel 360, 130578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2023.130578 (2024).

Goetz, V., Pupier, O. & Guillot, A. Carbon dioxide-methane mixture adsorption on activated carbon. Adsorption 12, 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10450-006-0138-z (2006).

Lu, X. C., Li, F. C. & Watson, A. T. Adsorption studies of natural gas storage in Devonian shales. SPE Formation Eval. 10(2), 109–113 (1995).

Rani, S., Padmanabhan, E. & Prusty, B. K. Review of gas adsorption in shales for enhanced methane recovery and CO2 storage. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 175, 634–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2018.12.081 (2019).

Pan, Z. & Connell, L. D. Reservoir simulation of free and adsorbed gas production from shale. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 22, 359–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2014.12.013 (2015).

Ou, C. & You, Z. Review of CO2 utilization and storage in adsorption-type unconventional natural gas reservoirs. Fuel 374, 132352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2024.132352 (2024).

Akbari, A., Maleki, M., Kazemzadeh, Y. & Ranjbar, A. Calculation of hydrogen dispersion in cushion gases using machine learning. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 13718. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98613-9 (2025).

Chalmers, G. R. & Bustin, R. M. Lower cretaceous gas shales in Northeastern British columbia, part I: geological controls on methane sorption capacity. Bull. Can. Pet. Geol. 56 (1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.2113/gscpgbull.56.1.1 (2008).

Ross, D. J. & Bustin, R. M. Characterizing the shale gas resource potential of Devonian–Mississippian strata in the Western Canada sedimentary basin: application of an integrated formation evaluation. AAPG Bull. 92 (1), 87–125. https://doi.org/10.1306/09040707048 (2008).

Yang, T., Nie, B., Yang, D., Zhang, R. & Zhao, C. Experimental research on displacing coal bed methane with supercritical CO2. Saf. Sci. 50 (4), 899–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2011.08.011 (2012).

Tambaria, T. N., Sugai, Y. & Nguele, R. Adsorption factors in enhanced coal bed methane recovery: A review. Gases 2(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/gases2010001 (2022).

Li, C., Qin, Y., Guo, T., Shen, J. & Yang, Y. Supercritical methane adsorption in coal and implications for the occurrence of deep coalbed methane based on dual adsorption modes. Chem. Eng. J. 474, 145931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.145931 (2023).

Zhou, F., Liu, S., Pang, Y., Li, J. & Xin, H. Effects of coal functional groups on adsorption microheat of coal bed methane. Energy Fuels. 29 (3), 1550–1557. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef502718s (2015).

Moore, T. A. Coalbed methane: a review. Int. J. Coal Geol. 101, 36–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2012.05.011 (2012).

Maleki, M., Dehghani, M. R., Akbari, A., Kazemzadeh, Y. & Ranjbar, A. Investigation of wettability and IFT alteration during hydrogen storage using machine learning. Heliyon https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e38679 (2024).

Akbari, A. Sustainable approaches to water management and water quality in hydraulic fracturing for unconventional oil and gas development in the united states: A critical review and compilation. Can. J. Chem. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjce.25646 (2025).

Akbari, A., Kazemzadeh, Y., Martyushev, D. A. & Cortes, F. Using ultrasonic and microwave to prevent and reduce wax deposition in oil production. Petroleum https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petlm.2024.09.002 (2024).

Mudoi, M. P., Sharma, P. & Khichi, A. S. A review of gas adsorption on shale and the influencing factors of CH4 and CO2 adsorption. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 217, 110897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2022.110897 (2022).

Babatunde, K. A., Negash, B. M., Jufar, S. R., Ahmed, T. Y. & Mojid, M. R. Adsorption of gases on heterogeneous shale surfaces: A review. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 208, 109466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2021.109466 (2022).

Bakshi, T. & Vishal, V. A review on the role of organic matter in gas adsorption in shale. Energy Fuels. 35, 15249–15264. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.1c01631 (2021).

Yang, Y. & Liu, S. Review of shale gas sorption and its models. Energy Fuels. 34 (12), 15502–15524. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c02906 (2020).

Akbari, A. The application of Radio-Frequency identification (RFID) technology in the petroleum engineering industry: mixed review. Petroleum Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ptlrs.2025.05.001 (2025).

Akbari, A., Ranjbar, A., Kazemzadeh, Y., Mohammadinia, F. & Borhani, A. Estimation of minimum miscible pressure in carbon dioxide gas injection using machine learning methods. J. Petroleum Explor. Prod. Technol. 15 (2), 25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-024-01915-3 (2025).

Zhang, X., Ranjith, P., Perera, M., Ranathunga, A. & Haque, A. Gas transportation and enhanced coalbed methane recovery processes in deep coal seams: a review. Energy Fuels. 30 (11), 8832–8849. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.6b01720 (2016).

Liu, S., Sun, B., Xu, J., Li, H. & Wang, X. Study on competitive adsorption and displacing properties of CO2 enhanced shale gas recovery: advances and challenges. Geofluids 2020(1), 6657995. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6657995 (2020).

Rother, G. et al. Pore size effects on the sorption of supercritical CO2 in mesoporous CPG-10 silica. J. Phys. Chem. C. 116 (1), 917–922. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp209341q (2012).

Ebrahimi, P., Ranjbar, A., Kazemzadeh, Y. & Akbari, A. Shale volume Estimation using machine learning methods from the Southwestern fields of Iran. Results Eng. 25, 104506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2025.104506 (2025).

Chalmers, G. R. & Bustin, R. M. The organic matter distribution and methane capacity of the lower cretaceous strata of Northeastern British columbia, Canada. Int. J. Coal Geol. 70, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2006.05.001 (2007).

Karami, A., Akbari, A., Kazemzadeh, Y. & Nikravesh, H. Enhancing hydraulic fracturing efficiency through machine learning. J. Petroleum Explor. Prod. Technol. 15 (2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-024-01914-4 (2025).

Wang, C., Zhao, Y., Wu, R., Bi, J. & Zhang, K. Shale reservoir storage of hydrogen: Adsorption and diffusion on shale. Fuel https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2023.129919 (2024).

Lu, C. G. et al. Investigations of methane adsorption characteristics on marine-continental transitional shales and gas storage capacity models considering pore evolution. Pet. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petsci.2024.03.027 (2024).

Zhang, Q. et al. Hydrogen and cushion gas Adsorption–Desorption dynamics on clay minerals. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 16 (40), 53994–54006. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.4c12931 (2024).

Zhou, Y., Hui, B., Shi, J., Shi, H. & Jing, D. Machine learning method for shale gas adsorption capacity prediction and key influencing factors evaluation. Phys. Fluids https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0184562 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. Lattice Boltzmann prediction of CO2 and CH4 competitive adsorption in shale porous media accelerated by machine learning for CO2 sequestration and enhanced CH4 recovery. Appl. Energy. 370, 123638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.123638 (2024).

Alqahtani, F. M., Youcefi, M. R., Djema, H., Nait Amar, M. & Ghasemi, M. Data-driven framework for predicting the sorption capacity of carbon dioxide and methane in tight reservoirs. Greenh. Gases Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1002/ghg.2318 (2024).

Alanazi, A., Ibrahim, A. F., Bawazer, S., Elkatatny, S. & Hoteit, H. Machine learning framework for estimating CO2 adsorption on coalbed for carbon capture, utilization, and storage applications. Int. J. Coal Geol. 275, 104297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2023.104297 (2023).

Kalam, S., Arif, M., Raza, A., Lashari, N. & Mahmoud, M. Data-driven modeling to predict adsorption of hydrogen on shale kerogen: implication for underground hydrogen storage. Int. J. Coal Geol. 280, 104386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2023.104386 (2023).

Amar, M. N., Larestani, A., Lv, Q., Zhou, T. & Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A. Modeling of methane adsorption capacity in shale gas formations using white-box supervised machine learning techniques. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 208, 109226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2021.109226 (2022).

Meng, M., Zhong, R. & Wei, Z. Prediction of methane adsorption in shale: Classical models and machine learning based models. Fuel 278, 118358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118358 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Data driven machine learning models for shale gas adsorption estimation. in SPE Europec featured at EAGE Conference and Exhibition? : SPE, D031S017R002 https://doi.org/10.2118/200621-MS (2020).

Aghaie, M. & Zendehboudi, S. Estimation of CO2 solubility in ionic liquids using connectionist tools based on thermodynamic and structural characteristics. Fuel 279, 117984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.117984 (2020).

Fang, L. et al. Effect of Machine Learning Algorithms on Prediction of In-Cylinder Combustion Pressure of Ammonia–Oxygen in a Constant-Volume Combustion Chamber. Energies 17(3), 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17030746 (2024).

Abdelrahim, A. I. & Yücel, Ö. "A machine learning based regression methods to predicting syngas composition for plasma gasification system. Fuel 381, 133575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2024.133575 (2025).

Soliman, A. A., Gomaa, S., Shahat, J. S., El Salamony, F. A. & Attia, A. M. New models for estimating minimum miscibility pressure of pure and impure carbon dioxide using artificial intelligence techniques. Fuel 366, 131374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2024.131374 (2024).

Zeng, C. et al. Predicting absolute adsorption of CO2 on jurassic shale using machine learning. Fuel 381, 133050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2024.133050 (2025).

Liu, M. et al. Prediction of CO2 storage in different geological conditions based on machine learning. Energy Fuels. 38 (22), 22340–22350. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.4c04274 (2024).

Prokhorenkova, L., Gusev, G., Vorobev, A., Dorogush, A. V. & Gulin, A. CatBoost: unbiased boosting with categorical features, Advances Neural inf. Process. syst. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2018/hash/14491b756b3a51daac41c24863285549-Abstract.html (2018).

Mok, J., Go, W. & Seo, Y. Predicting phase equilibria of CO2 hydrate in complex systems containing salts and organic inhibitors for CO2 storage: A machine learning approach. Energy Fuels. 38 (6), 5322–5333. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.3c04930 (2024).

Najafzadeh, M. & Mahmoudi-Rad, M. Residual energy evaluation in vortex structures: on the application of machine learning models. Results Eng. 23, 102792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.102792 (2024).

Esfandi, T., Sadeghnejad, S. & Jafari, A. Effect of reservoir heterogeneity on well placement prediction in CO2-EOR projects using machine learning surrogate models: benchmarking of boosting-based algorithms. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 233, 212564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoen.2023.212564 (2024).

Al Saleem, M., Harrou, F. & Sun, Y. Explainable machine learning methods for predicting water treatment plant features under varying weather conditions. Results Eng. 21, 101930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.101930 (2024).

Ghasabehi, M. & Shams, M. Predicting water saturation and oxygen transport resistance in proton exchange membrane fuel cell by artificial intelligence. Fuel 368, 131557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2024.131557 (2024).

Freund, Y., Schapire, R. & Abe, N. A short introduction to boosting. Journal-Japanese Soc. Artif. Intell. 14, 771–780 (1999). http://www.yorku.ca/gisweb/eats4400/boost.pdf

Khan, M. et al. Forecasting the strength of graphene nanoparticles-reinforced cementitious composites using ensemble learning algorithms. Results Eng. 21, 101837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.101837 (2024).

Sun, X., Xie, M., Zhou, F., Fu, J. & Liu, J. Multi-objective optimization for combustion, thermodynamic and emission characteristics of Atkinson cycle engine using tree-based machine learning and the NSGA II algorithm. Fuel 342, 127839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2023.127839 (2023).

Tariq, Z. et al. An experimental study and machine learning modeling of shale swelling in extended reach wells when exposed to diverse Water-Based drilling fluids. Energy Fuels. 38 (5), 4151–4166. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.3c05129 (2024).

Wudil, Y. Ensemble learning-based investigation of thermal conductivity of Bi2Te2. 7Se0. 3-based thermoelectric clean energy materials. Results Eng. 18, 101203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101203 (2023).

Yu, J. et al. Mining the synergistic effect in hydrothermal co-liquefaction of real feedstocks through machine learning approaches. Fuel 334, 126715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2022.126715 (2023).

Geurts, P., Ernst, D. & Wehenkel, L. Extremely randomized trees. Machine Learning 63, 3–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10994-006-6226-1 (2006).

Sukpancharoen, S. et al. Data-driven prediction of electrospun nanofiber diameter using machine learning: A comprehensive study and web-based tool development. Results Eng. 24, 102826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.102826 (2024).