Abstract

The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics of remimazolam (RMZ), a novel ultrashort-acting anesthetic, administration alone in clinical practice remain poorly understood. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the relationship between patient characteristics and the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of RMZ in older Japanese adults who underwent general anesthesia at the early stage of infusion. Plasma samples were collected from 20 patients (median age: 71.7 years; range: 42.2–88.6 years) who were intravenously administered RMZ without other anesthetics such as remifentanil or fentanyl. The pharmacokinetic profiles of RMZ and its metabolite (CNS7054) were described using three- and two-compartment models with a transit compartment, respectively. The bispectral index was selected as a clinical measure of sedation. The pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic profile of RMZ was described using a maximum inhibitory model with an effect compartment. The population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters of RMZ were obtained using the nonlinear mixed-effects modeling program. RMZ clearance (CL) was increased nonlinearly with increasing body weight (BW), and the population mean CL for a typical patient (BW, 60.4 kg) was 1.38 L/min. No patient characteristics affected CNS7054 pharmacokinetics. The population mean of the half-maximal inhibitory RMZ concentration decreased nonlinearly with increasing age or BW. However, these characteristics did not meet the criteria for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic covariates. Our results suggest that BW is an intrinsic factor affecting RMZ pharmacokinetics in Japanese patients under general anesthesia in the early stages of infusion; however, no patient characteristics affected RMZ pharmacodynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

General anesthesia is a medicinal treatment that renders patients completely unconscious, preventing patient movement and pain perception during surgery. The depth of anesthesia during surgery is associated with prognosis after surgery1,2. Therefore, controlling the anesthetic depth during surgery is crucial to improving patient survival and reducing morbidity. Propofol is a common intravenous anesthetic; however, it causes adverse events, such as potentially fatal conditions, owing to its administration (injection syndrome), injection pain, and hemodynamic instability3,4. Midazolam is occasionally used as an intravenous anesthetic; its application is limited by the prolonged anesthetic effect of its active metabolites5.

Remimazolam (RMZ), a novel ultra-short-acting anesthetic, is intravenously administered to induce and maintain general anesthesia6,7. Clinical trials have demonstrated that in contrast to propofol, RMZ does not cause notable injection pain8. Additionally, a pharmacological analysis revealed that the offset of RMZ after the cessation of infusion was faster than that of midazolam owing to its rapid hydrolysis by carboxylesterase (CES) 1 in the liver and lungs to an inactive metabolite (CNS7054)9 and similar to that of propofol10. Therefore, the clinical safety and efficacy of RMZ are superior to those of propofol and midazolam.

Population pharmacokinetic and/or pharmacodynamic analysis is a quantitative method for determining inter-individual variability in drug concentrations, effects, and adverse events. Several pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analyses involving clinical trial data have demonstrated that the plasma RMZ concentration is associated with its anesthetic effects11,12,13,14. In the population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analyses of healthy participants and those who undergo surgery, body weight (BW), age, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status as an index of anesthetic depth, sex, and extracorporeal circulation may affect the inter-individual variability in RMZ pharmacokinetics11,13,14. In contrast, race, body mass index (BMI), and cumulative RMZ dose affect inter-individual variability in RMZ pharmacodynamics11,13. However, the population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analyses in patients who underwent surgery under general anesthesia were conducted under the concomitant use of RMZ with remifentanil, which was intravenously administered during general anesthesia15; therefore, the anesthetic effect of remifentanil on RMZ pharmacodynamics could not be evaluated separately. In addition, the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics of RMZ administration alone in clinical practice remain poorly understood.

Considering the intravenous administration of RMZ alone at an early stage of infusion according to the package insert, this study aimed to evaluate the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of RMZ in older Japanese adults who underwent general anesthesia.

Materials and methods

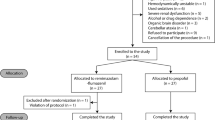

Patients and study design

This clinical study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Review Board of Ritsumeikan University Biwako-Kusatsu Campus (approval number BKC-IRB-2020-084), the Ethical Review Committee of Yamagata University Faculty of Medicine (Approval number 2020 − 284). All participants provided written informed consent.

Adult Japanese patients subjected to general anesthesia with RMZ at Yamagata University Hospital between April 2021 and October 2022 were enrolled in this study. RMZ besylate injectable preparations (Anerem®; Mundipharma K.K., Tokyo, Japan) were intravenously infused at 12 mg/kg/h (0.2 mg/kg/min) into patients until the loss of consciousness and subsequently at 1.0 mg/kg/h (0.017 mg/kg/min) to maintain anesthesia without other anesthetics such as remifentanil or fentanyl. Loss of consciousness was defined as no response to calls after the infusion of RMZ besylate. Blood specimens were collected in tubes containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid at 1, 3, and 5 min after the loss of consciousness. After drawing the last sample, remifentanil or fentanyl was concomitantly administered to patients receiving RMZ. Clinical laboratory data were retrospectively collected from the patients’ electronic medical records, including age, BW, BMI, and sex, as well as serum creatinine (Scr), creatinine clearance (CLcr), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels. The Cockcroft–Gault equation was used to calculate the CLcr16. Patients with severe liver cirrhosis (Child-Pugh score of C) were excluded.

Quantitative analyses

Blood samples from patients were centrifuged at 2,500 ×g for 10 min to obtain plasma specimens and stored at -80 °C until analyses. The plasma concentrations of RMZ and CNS7054 were measured using high-performance liquid chromatography with electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), as previously reported with some modifications11. Briefly, 2H4- RMZ and 2H4-CNS7054 as internal standards were prepared in methanol and diluted stepwise with an acetonitrile/water mixture (1:1, v/v). To 300 µL aliquots of the plasma sample, 15 µL of 2H4- RMZ solution (2,000 ng/mL) and 2H4-CNS7054 (5,000 ng/mL) were added. Subsequently, 330 µL of 4% phosphoric acid was added. RMZ and CNS-7054 were extracted from the mixture using Oasis® PRiME HLB (Waters Co., Milford, MA, USA) as a solid phase extraction cartridge for the clean-up according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Subsequently, 180 µL aliquots of the elute were diluted with 200 µL of water, from which a 20 µL sample solution was injected into the LC-MS/MS system after filtration. LC-MS/MS was performed using an Agilent 1200 Infinity series LC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, USA) coupled to an API3200 triple-quadruple mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, Foster City, California, USA). Chromatographic separations were achieved with an XSelect CSH C18 (2.1 × 100 mm, particle size 3.5 μm; Waters Co.) with an XSelect CSH C18 VanGuard Cartridge (2.1 mm×5 mm, particle size 3.5 μm; Waters Co.) at 40 °C. The analytes were eluted under isocratic conditions at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min using a mobile phase A: mobile phase B ratio of 50:50 (v/v). Mobile phase A was water containing 0.1% formic acid and 10 mmol/L ammonium formate, whereas mobile phase B was acetonitrile. MS/MS was conducted in the multiple reaction monitoring mode with a positive ion mode for determination. The electrospray ionization voltage was 5,000 V, and its temperature was maintained at 550 °C. The collision energies for RMZ, 2H4- RMZ, CNS7054, and 2H4-CNS7054 were 41, 41, 39, and 47 eV, respectively, and their declustering potentials were 51, 66, 66, and 66 V, respectively. The molecules were detected according to the following mass transitions: 440.6 > 363.1 (RMZ); 444.2 > 366.6 (2H4- RMZ); 426.1 > 363.0 (CNS7054); and 430.1 > 366.9 (2H4-CNS7054). The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation for RMZ were 0.5 − 4.4% and 2.4 − 8.7%, respectively. The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation for CNS7054 were 1.6 − 4.0% and 3.5 − 9.1%, respectively. The accuracy biases for RMZ and CNS7054 were within 92.6 − 104.6% and 92.4 − 100.8%, respectively. The calibration curves of RMZ and CNS7054 were linear at 5–2,000 and 20–2,000 ng/mL, respectively. When the plasma concentration of RMZ or CNS7054 exceeded the upper limit of quantification, the sample was diluted with blank plasma and reanalyzed. The bispectral index (BIS) was selected as a clinical measure of sedation and determined using the BIS model A-2000 XP (version 2.21; Aspect Medical Systems, Boston, MA, USA)17.

Population Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis

Sequential population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analyses were conducted using the nonlinear mixed-effects modeling (NONMEM) program (version 7.3.0; ICON Public Limited Company, Dublin, Ireland) with a first-order conditional estimation method with interaction. An overview of the basic pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic models for RMZ is shown in Fig. 1. The pharmacokinetic profiles of RMZ and CNS7054 were described using three- and two-compartment models with a transit compartment, respectively, to explain CNS7054 formation, as previously reported with some modifications11. The pharmacokinetic model was parameterized by eliminating the clearances (CL) of RMZ and CNS7054 (CLM), transit rate constant (kT), central and peripheral volumes of distribution of RMZ (V1, V2 and V3), central and peripheral volumes of CNS7054 (V1M and V2M), and intercompartmental CL of RMZ (Q2, Q3, and Q2M). An effect compartment was used as the action site, and the rate constant of distribution from the plasma to the effect site (kE0) of RMZ was parameterized. Residual variabilities (ε) for the plasma concentrations of RMZ and CNS7054 were described using an exponential error model as follows:

where \({C_{ij}}\)and \(\overline {{{C_{ij}}}}\) represent the observed and predicted concentrations of RMZ or CNS7054 in the jth record of ith patient, respectively. Inter-individual variabilities (η) for the pharmacokinetic parameters were described using an exponential error model as follows:

where \({P_i}\), \({\theta _{Pi}}\), and \({\eta _{Pi}}\)represent the pharmacokinetic parameter, its population mean estimates, and η of the ith patient, respectively. The parameters kT, V3, V2M, Q2, Q3, and Q2M were fixed at the reported values of 0.024 min-1, 15.5 L, 7.4 L/75 kg, 1.04 L/min, 0.19 L/min, and 0.13 L/min/75 kg owing to the lack of individual data11. Covariate analysis was conducted to evaluate the effects of continuous clinical laboratory data, including age, BW, and BMI, as well as Scr, CLcr, ALT, and AST levels, on pharmacokinetic parameters using the following equation:

where COVi and COVmedian are the covariates of the ith patient and the median of the covariate, respectively, and \({\theta _{COV}}\)is the population mean estimate. BW was included allometrically on all disposition parameters, in which the \({\theta _{COV}}\)for clearance and volume of distribution were set to 0.75 and 1, respectively. For categorical covariates such as sex, the dichotomous parameter A was set to 0 for the normal classification and 1 for the other classifications for each individual, as follows:

Overview of the basic pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic model for remimazolam (RMZ). CL, elimination clearance of RMZ; CLM, elimination clearance of CNS7054; Q2 and Q3, intercompartmental clearance of RMZ; Q2M; intercompartmental clearance of CNS7054; kT, transit rate constant; kE0, rate constant of distribution from plasma to the effect site; V1, central volume of distribution of RMZ; V2 and V3, peripheral volume of distribution of RMZ; V1M, central volume of distribution of CNS7054; peripheral volume of distribution of CNS7054; BIS, bispectral index.

The influence of each covariate on the population mean parameters was evaluated using stepwise forward inclusion and backward elimination methods, and the statistical significance was set at 0.05, with 1 degree of freedom if the objective function value (OBJ) decreased by > 3.84. Subsequently, using a backward stepwise selection method, covariates were removed from the full model. Statistical significance was set at 0.01, with one degree of freedom if the OBJ decreased by > 6.63.

After the final population pharmacokinetic model was developed, the BIS-time profiles after starting the RMZ infusion were modeled using individual Bayesian estimated pharmacokinetic parameters18,19. The RMZ concentrations at the effect site and BIS were described using a direct maximum effect model as follows:

where \(\overline {{BI{S_{ij}}}}\), \({C_E}_{{_{{ij}}}}\), \(E{C_{50}}\), and \(E{C_{\hbox{max} }}\) represent the predicted BIS values and predicted RMZ concentrations in the jth record of ith patient, the half-maximal effective concentration, and the maximum effect based on the Bayesian approach, respectively. The residual variability of the BIS was described using an exponential error model. Covariate analysis was conducted using the same method used for population pharmacokinetic analysis.

Model evaluation

Goodness-of-fit plots were used to assess the adequacy of the model. A prediction-corrected visual predictive check (pcVPC) and nonparametric bootstrap analysis were used to assess the final model. In the pcVPC, 1,000 hypothetical datasets were simulated via random sampling using NONMEM. In the bootstrap analysis, 1,000 replication datasets were generated via random sampling using Perl-speaks-NONMEM version 4.7.020.

Model-based simulation

A Monte Carlo simulation was used to evaluate the effect of BW on plasma RMZ concentrations and the effect site and BIS. Using the NONMEM program, 1,000 pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles were simulated for patients with various BW values (40, 60, and 80 kg). According to the package insert, the infusion rate of RMZ was set to 12 mg/kg/h for induction and 1 mg/kg/h for maintenance. The target range of BIS was set to 40−6021.

Results

Patient characteristics

Sixty plasma concentration datasets for RMZ and CNS7054 and 60 BIS measurements from 20 patients who underwent general anesthesia were analyzed. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Fourteen patients (70.0%) were aged 65 years or older. One sample for RMZ concentration exceeded the upper limit of quantification, and the sample was diluted with blank plasma and reanalyzed.

Population Pharmacokinetic modeling

In the preliminary analysis, the lowest OBJ was calculated using the basic model where the inter-individual variabilities for V2, V3, Q2, Q3, kT, V2M and Q2M were removed from Eq. 2. Compared with that of the basic model, the OBJs of the covariate model incorporating BW into the CL using Eq. 3 were decreased significantly by 12.81. Additionally, stepwise forward inclusion and backward elimination methods showed that BW significantly affected the CL of RMZ, whereas other covariates, such as age, sex, BMI, Scr, CLcr, ALT, and AST, did not affect the pharmacokinetics of RMZ. No covariates affected the pharmacokinetics of CNS7054. The population pharmacokinetic parameter estimates for RMZ and CNS7054 in Japanese patients who underwent general anesthesia at the early stage of infusion are presented in Tables 2 and 3. The CL of the RMZ allometrically increased as the BW increased, and the population mean CL for a typical patient (BW 60.4 kg) was 1.38 L/min. The inter-individual variabilities for CL, V1, CLM, and V1M were 16.3, 89.9, 66.7, and 57.6%, respectively. The residual variabilities for RMZ and CNS7054 were 8.8 and 9.2%, respectively.

Population pharmacodynamic modeling

In the preliminary analysis, the lowest OBJ was calculated using the basic model where the inter-individual variability for Emax was removed from Eq. 2. Compared with that of the basic model, the OBJs with the covariate model incorporating age or BW into EC50 using Eq. 3 were decreased by 4.74 or 4.85, respectively. However, the stepwise forward inclusion and backward elimination methods showed that age and BW had no impacts on the EC50 of RMZ. Additionally, other covariates, except for age and BW, did not affect the pharmacodynamics of RMZ. The population pharmacodynamic parameter estimates for the BIS in Japanese patients who underwent general anesthesia at the early stage of infusion are presented in Table 4. The population mean EC50 of RMZ was 79.6 ng/mL. The inter-individual variability for EC50 was 35.1%, and the residual variability for BIS was 13.8%.

Model evaluation

The goodness-of-fit and pcVPC suggested that the population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic models accurately and adequately predicted the observed RMZ and CNS7054 concentrations, as well as the BIS (Figs. 2 and 3). Additionally, the median values of the population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters from 1,000 bootstrap re-samplings were similar to the mean estimates in the final pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic models (Table 2).

Goodness-of-fit plots of the final pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic model. Observed plasma concentrations of RMZ or CNS7054 versus population predictions (a and e) or individual predictions (b and f), as well as conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) versus time after infusion (c and g) or population predictions of RMZ or CNS7054 (d and h). Observed BIS versus population predictions (i) or individual predictions (j), and CWRES versus time after infusion (k) or population predictions (l). The open circles show the observed values, and each dotted line indicates a line of identity.

Prediction-corrected visual predictive check plot of the final pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic model. Open circles show the observed plasma concentrations (a and b) or bispectral index (BIS) (c) The top dotted, middle solid, and bottom dotted lines represent the 95th, 50th, and 5th percentiles, respectively, calculated from 1000 simulated datasets.

Model-based simulation

Figure 4 shows the simulated plasma RMZ concentrations and the effect site and BIS-time profiles in the 1,000 replication datasets of patients weighing 40, 60, and 80 kg subjected to general anesthesia (induction, 12 mg/kg/h; maintenance, 1 mg/kg/h). The predicted concentration-time profiles for plasma RMZ and the effect site increased with BW. The predicted BIS time profiles in patients weighing 40 kg were slightly higher than those in patients weighing 60 or 80 kg, whereas the time to reach the upper limit of the target BIS (60) in patients whose weights ranged from 40 to 80 kg was within 2 min.

Simulations of plasma RMZ concentrations and the effect site (a and b) and BIS-time profiles (c) in the 1000 replication datasets of a patient administered for general anesthesia with induction (12 mg/kg/h) and maintenance (1 mg/kg/h). The time to loss of consciousness was set to 1.71 min after the infusion. These simulations were conducted using the final pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic model. The solid, dotted and bold lines indicate the medians in patients weighing 40, 60 and 80 kg, respectively. In (c), the shaded area shows the target range of BIS (40−60)21.

Discussion

This study aimed to characterize the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of RMZ at an early stage of infusion in Japanese patients who underwent general anesthesia. Several population pharmacokinetic studies have shown that the plasma concentration-time profiles of RMZ after intravenous administration can be described using a three-compartment model with14 or without11,13 a virtual venous compartment connected to the central compartment. Schüttle et al. described the pharmacokinetic profiles of CNS7054 using a two-compartment model with a transit compartment11. In this study, preliminary analyses were conducted to determine the optimal population pharmacokinetic models for RMZ (one-, two- or three-compartment models) and CNS7054 (one- or two-compartment models with or without a transit compartment), based on Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC). As shown in Supplementary Table 1, the model with the lowest AIC value—Basic Model 1—was selected. Accordingly, the pharmacokinetic profiles of RMZ and CNS7054 were described using three- and two-compartment models with a transit compartment, respectively. The pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic profile of RMZ was described using a maximum inhibitory model with an effect compartment. Although age has been reported to influence inter-individual variability in RMZ pharmacokinetics, the literature presents conflicting findings regarding this effect13,14. In the present study, the majority of patients were over 65 years of age; however, pharmacokinetic parameters such as kT, V3, V2M, Q2, Q3, and Q2M were fixed values previously reported for healthy young adults11.

Our results indicated the impact of the patient’s BW on the CL of the RMZ, as well as the V2M and Q2M of CNS7054 (Tables 2 and 3). The population mean of RMZ CL for patients (BW, 60.4 kg) in this study was 1.38 L/min, where the CL was similar to that for healthy and surgical participants in previous population pharmacokinetic analyses (0.88–1.14 L/min)11,13,14. No covariate models affected RMZ V1 and V2. The mean V1 (6.38 L) was slightly larger than that for healthy and surgical participants in previous population pharmacokinetic analyses (2.92–4.7 L)11,13,14, whereas the mean V2 (4.11 L) was smaller than that for healthy and surgical participants (11.3–19.1 L)11,13,14. Additionally, the mean pharmacokinetic parameters of CNS7054 in this study were similar to those of healthy participants11. In our study, age did not have an impact on the pharmacokinetics of RMZ and CNS7054. Bootstrap and pcVPC analyses showed that the final population pharmacokinetic model provided a robust and unbiased fit to the data (Figs. 2 and 3; Tables 2 and 3). These findings suggest that age is not a critical intrinsic factor affecting the pharmacokinetics of RMZ and CNS7054. These results suggest that the pharmacokinetics of RMZ in Japanese patients who underwent general anesthesia at the early stage of infusion is affected by RMZ distribution to tissues rather than by CES1 activity. The protein expression and activity of CES1 have large inter-individual variabilities, which are intrinsic factors that affect the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drugs metabolized by CES122. Therefore, additional studies are needed to clarify the relative contributions of distribution and CES1 activity to the inter-individual variability of RMZ.

The population mean EC50 of RMZ in patients at an early stage of infusion was 79.6 ng/mL (Table 4), which was lower than that (520 ng/mL) in healthy and surgical participants who were administered with RMZ and remifentanil for up to 24 h13. This clinical trial indicated that EC50 elevated with increasing cumulative RMZ dose, suggesting that high sensitivity to RMZ occurs at the early stage of infusion. The population mean EC50 of RMZ tended to decrease nonlinearly as age or BW increased. However, these characteristics did not meet the criteria for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic covariates (Table 4). Regarding patients’ age, in the preliminary analysis, the time to loss of consciousness after starting the infusion was significantly negative association with age (P = 0.049), and the median of the time in patients aged ≥ 70 years was shorter than that in patients aged < 70 years (P = 0.118 by Mann–Whitney U test; Supplementary Fig. 1). These results suggest that age is not an intrinsic factor affecting RMZ pharmacodynamics; however, the intravenous administration of RMZ to older patients requires more care than that to young patients to avoid unexpected adverse events.

The present simulation study showed that using the final model, the predicted RMZ concentration-time profiles in the plasma and effect site had large variabilities, whereas the predicted BIS-time profiles had relatively small variability (Fig. 4). As the predicted RMZ concentrations at the effect site in the virtual patients were higher than the EC50 value within 1 min, the time to reach the target BIS was similar among the virtual patients. These results suggest that the inter-individual variability in RMZ pharmacodynamics at the early stage of infusion is smaller than that in RMZ pharmacokinetics, and that the anesthetic effect of RMZ may be similar among patients during this early stage when administered according to the package insert. However, because of unexplained inter-patient variability in the present model, BIS should be carefully monitored after initiating treatment at the recommended starting dose.

Our study has some limitations. First, the number of patients and the amount of data for each patient were small. Second, the effects of the administration period and concomitant medications, such as remifentanil and midazolam, on RMZ pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics were not examined because the administration period was short. Third, although RMZ is reported to be approximately 92% bound to plasma proteins, predominantly serum albumin23, the impact of albumin levels on RMZ pharmacokinetics could not be assessed in this study, as serum albumin levels were not collected according to a predefined protocol. The population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of RMZ in a larger Japanese population require to be examined in the future.

Nonetheless, our results suggest that BW is an intrinsic factor affecting RMZ pharmacokinetics in Japanese patients under general anesthesia at the early stages of infusion; however, no patient characteristics affected RMZ pharmacodynamics. These results may help to prevent the adverse events associated with RMZ.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Leslie, K., Myles, P. S., Forbes, A. & Chan, M. T. The effect of bispectral index monitoring on long-term survival in the B-aware trial. Anesth. Analg. 110, 816–822. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181c3bfb2 (2010).

Kertai, M. D. et al. Association of perioperative risk factors and cumulative duration of low bispectral index with intermediate-term mortality after cardiac surgery in the B-Unaware trial. Anesthesiology 112, 1116–1127. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181d5e0a3 (2010).

Basaranoglu, G., Erden, V., Delatioglu, H. & Saitoglu, L. Reduction of pain on injection of Propofol using meperidine and remifentanil. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 22, 890–892. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265021505231502 (2005).

Li, X. et al. Effect of Dexmedetomidine for Attenuation of Propofol injection pain in electroconvulsive therapy: a randomized controlled study. J. Anesth. 32, 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00540-017-2430-3 (2018).

Bauer, T. M. et al. Prolonged sedation due to accumulation of conjugated metabolites of Midazolam. Lancet 346, 145–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91209-6 (1995).

Rex, D. K. et al. A phase III study evaluating the efficacy and safety of remimazolam (CNS 7056) compared with placebo and Midazolam in patients undergoing colonoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 88, 427–437e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2018.04.2351 (2018).

Doi, M. et al. Efficacy and safety of remimazolam versus Propofol for general anesthesia: a multicenter, single-blind, randomized, parallel-group, phase iib/iii trial. J. Anesth. 34, 543–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00540-020-02788-6 (2020).

Antonik, L. J., Goldwater, D. R., Kilpatrick, G. J., Tilbrook, G. S. & Borkett, K. M. A placebo- and midazolam-controlled phase I single ascending-dose study evaluating the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of remimazolam (CNS 7056): part I. Safety, efficacy, and basic pharmacokinetics. Anesth. Analg. 115, 274–283. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e31823f0c28 (2012).

Kilpatrick, G. J. et al. CNS 7056: A novel ultra-short-acting benzodiazepine. Anesthesiology 107, 60–66. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.anes.0000267503.85085.c0 (2007).

Wesolowski, A. M., Zaccagnino, M. P., Malapero, R. J., Kaye, A. D. & Urman, R. D. Remimazolam: Pharmacologic considerations and clinical role in anesthesiology. Pharmacotherapy 36, 1021–1027. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1806 (2016).

Schüttler, J. et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of remimazolam (CNS 7056) after continuous infusion in healthy male volunteers: part I. pharmacokinetics and clinical pharmacodynamics. Anesthesiology 132, 636–651. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000003103 (2020).

Eisenried, A., Schüttler, J., Lerch, M., Ihmsen, H. & Jeleazcov, C. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of remimazolam (CNS 7056) after continuous infusion in healthy male volunteers: part II. Pharmacodynamics of electroencephalogram effects. Anesthesiology 132, 652–666. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000003102 (2020).

Zhou, J. et al. Population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling for remimazolam in the induction and maintenance of general anesthesia in healthy subjects and in surgical subjects. J. Clin. Anesth. 66, 109899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2020.109899 (2020).

Masui, K., Stöhr, T., Pesic, M. & Tonai, T. A population Pharmacokinetic model of remimazolam for general anesthesia and consideration of remimazolam dose in clinical practice. J. Anesth. 36, 493–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00540-022-03079-y (2022).

Beers, R. A., Calimlim, J. R., Uddoh, E., Esposito, B. F. & Camporesi, E. M. A comparison of the cost-effectiveness of remifentanil versus Fentanyl as an adjuvant to general anesthesia for outpatient gynecologic surgery. Anesth. Analg. 91, 1420–1425. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000539-200012000-00022 (2000).

Cockcroft, D. W. & Gault, M. H. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 16, 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1159/000180580 (1976).

Matsushita, S., Oda, S., Otaki, K., Nakane, M. & Kawamae, K. Change in auditory evoked potential index and bispectral index during induction of anesthesia with anesthetic drugs. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 29, 621–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-014-9643-x (2015).

Zhang, L., Beal, S. L. & Sheiner, L. B. Simultaneous vs. sequential analysis for population PK/PD data I: best-case performance. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 30, 387–404. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOPA.0000012998.04442.1f (2003).

Zhang, L., Beal, S. L. & Sheinerz, L. B. Simultaneous vs. sequential analysis for population PK/PD data II: robustness of methods. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 30, 405–416. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOPA.0000012999.36063.4e (2003).

Lindbom, L., Pihlgren, P. & Jonsson, E. N. PsN-Toolkit–a collection of computer intensive statistical methods for non-linear mixed effect modeling using NONMEM. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 79, 241–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2005.04.005 (2005).

Yim, S. et al. Remimazolam to prevent hemodynamic instability during catheter ablation under general anesthesia: a randomized controlled trial. Can. J. Anaesth. 71, 1067–1077. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-024-02735-z (2024).

Her, L. & Zhu, H. J. Carboxylesterase 1 and precision pharmacotherapy: pharmacogenetics and nongenetic regulators. Drug Metab. Dispos. 48, 230–244. https://doi.org/10.1124/dmd.119.089680 (2020).

Kilpatrick, G. J. Remimazolam: Non-Clinical and clinical profile of a new sedative/anesthetic agent. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 690875. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.690875 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The research expenses of this study were supported by the Ritsumeikan University and Yamagata University. We wish to thank the Cactus Communications (www. editage.jp) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. U., Y. M., K. K., and M. K. conceived and designed the study. All authors were involved in the data analysis and interpretation. Y. M. and K. K. were involved in data acquisition. S. U., D. H., Y. M., K. K., and M. K. critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have approved this version of the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The Authors K. K. and M. K. were kindly gifted remimazolam, CNS-7054, and their internal standards from Paion UK Ltd. (Richmond, United Kingdom). Other authors have no competing interest.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Review Board of Ritsumeikan University Biwako-Kusatsu Campus (approval number BKC-IRB-2020-084) and the Ethical Review Committee of Yamagata University Faculty of Medicine (Approval number 2020–284).

Consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ueshima, S., Nagahara, S., Nakaya, K. et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characterization of remimazolam in older Japanese adults who underwent general anesthesia at early stage of infusion. Sci Rep 15, 24979 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10015-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10015-z