Abstract

Urban forests serve as a nature-based solution for mitigating climate change. The active participation of diverse community groups, especially women in the conservation of these resources is essential for effectively addressing climate-related challenges. Female high school students, as a critical demographic within the community, can significantly contribute to the management of urban forests, thereby facilitating the achievement of multiple sustainable development goals including SDG 5, SDG 11, SDG 13, SDG 15, and SDG 17. This study explores the behavioral intentions of female high school students in conserving urban forests for climate change mitigation, addressing a critical research gap in understanding the role of youth, particularly females, in environmental conservation. Employing an extended Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) model, this research integrates Environmental Awareness (EA) and Social Responsibility (SR) alongside traditional TPB constructs to enhance explanatory power. Data was collected from 370 students through a structured questionnaire and analyzed using structural equation modeling. Results reveal that attitudes, perceived behavioral control, EA, and SR significantly influence students’ intentions, while subjective norms show no significant effect. The extended model explains 64.9% of the variance in behavioral intentions, a 21.2% improvement over the initial TPB model. These findings underscore the importance of fostering environmental awareness, cultivating a sense of responsibility, and equipping female students with the skills necessary to contribute to urban forest conservation. The study offers actionable insights for policymakers and educators to design targeted initiatives that empower female youth as agents of change in climate action.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change stands as one of the most critical environmental crisis specially in cities, presenting unparalleled concerns that necessitate immediate action from all segments of society1,2,3. This phenomenon has resulted in economic, health, and environmental damages4,5,6,7,8. Cities, while being primary contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, also have the potential to lead efforts in combating climate change9,10,11. Various solutions have been proposed to mitigate the outcomes of this crisis in cities9,12,13among which the development and conservation of urban forests are recognized as an important strategy14,15,16. Urban forests, comprising green spaces, in and around the urban areas17have emerged as critical assets in this endeavor, offering a range of ecological, economic, and social benefits to serve citizens with nature-based solutions for climate change14,18,19,20,21,22,23.Therefore, urban forests conservation can enhance their functionality in combating climate change. Engaging the community specially young people in this conservation effort is an effective solution to achieve this goal24.

Young people, especially students, as a key segment of youth, play a critical role in efforts to mitigate climate change impacts25,26,27. Research indicates that young individuals, particularly students, exhibit a high level of awareness regarding climate change and a strong inclination to take responsibility for addressing its challenges28,29,30. The various behaviors such as green product consumption31,32,33preserving the agricultural landscape34perception towards forestation35and environmental behaviors of tourists36 are among the most privilege behaviors to combat climate change among young people. In society, young female students constitute a significant segment of society, whose participation and engagement in addressing climate change are of considerable importance28,37,38,39. Therefore, the student population, particularly female students, offers unique perspectives, strengths, and potential to contribute to climate change mitigation40given that gender serves as a strong influencing factor in addressing environmental challenges41,42. The participation of female students in environmental issues such as urban forest conservation is essential for achieving multiple objectives of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), significantly contributing to the gender equality (SDG 5), sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11), climate action (SDG 13), life on land (SDG 15), and partnerships for the goals (SDG 17)43,44. Despite the critical importance of women’s participation in climate change mitigation efforts, gender inequality persists both in the negative impacts45 of climate change and in the involvement in addressing these challenges. In developing countries specially, various factors such as cultural limitations, social constraints, and prevailing subjective norms regarding the role of women restrict their participation in activities related to climate change mitigation and environmental protection46,47,48.

Iran, as a developing country, is experiencing the impacts of climate change in different parts of country including Khorramabad, which suffers from climate change consequences such as dust storms, effects on agriculture, and climate-induced migration49,50. In these areas, forest conservation both in natural landscapes and urban settings, has been recognized as a key strategy for addressing climate change51,52. Despite the presence of a traditionally structured society, women and specially female students in these regions have demonstrated a growing willingness in recent decades to actively participate in environmental conservation initiatives, urban forest protection, and climate change mitigation efforts53,54,55. Utilizing the potential of women, particularly female students who represent the future generation in addressing climate change, necessitates a comprehensive analysis of the determinants influencing their behavioral intentions toward climate change mitigation actions, as well as their involvement in collective initiatives. Various studies have examined the environmental behaviors of students aimed at protecting the environment or combating climate change. These studies have explored behaviors such as sustainable consumption, understanding of climate change28,41,56the choice of responsible travel and consumption57,58,59and participation in collective actions60,61,62 to combat climate change. They have confirmed the influence of behavioral factors on students’ intentions and actions in these areas.

Although limited studies have explored the role of women in addressing climate change, a significant research gap persists in this area, as highlighted by review articles63. This gap is particularly evident in the examination of female students’ behavioral intentions to participate in urban forest conservation as a strategy for climate change mitigation. Addressing this research gap is crucial, as high school students represent the next generation of leaders in climate change mitigation64. Moreover, tackling climate change without the active involvement of women, who constitute half of society’s population, is impossible25,65. This study aims to bridge the existing research gap by examining the determinants of female students’ intentions to combat climate change through urban forest conservation. By understanding factors influencing their intentions, policy makers and managers can effectively engage students in sustainable practices for climate change mitigation. Urban forests conservation as pivotal element for mitigating climate change66,67are among the most important fields for participating female students to combat climate change68. Investigating the involvement of female students in urban forest conservation enables the development of strategies to bolster the resilience and efficacy of these ecosystems, thereby advancing overarching climate change mitigation objectives. Hence, this research was designed to (1) explore behavioral intention of female high school students engaged in urban forest conservation, by (2) extending the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) model by incorporating new components and (3) assessing the influence of these new components on the students’ intention. The study seeks to examine the influence of psychological factors on behavioral intention of female students.

Theoretical framework

To conduct this study, a developed model was utilized by integrating the TPB and the Knowledge-Attitude-Behavior (KAP) Theory. This study aimed to investigate the influence of environmental/awareness on attitudes, a fundamental component of the TPB, in shaping behavioral intentions. Furthermore, it sought to identify the key determinants of female students’ behavioral intentions toward urban forest conservation. The TPB is a behavioral model used to examine the factors that shape individuals’ behavioral intentions and actions69. This theory has been employed to investigate intentions to engage in environmental activities such as forest conservation70purchasing green products by different generations33,71coping with natural hazards72adopting agroforestry practices73,74and understanding climate change (Jacob et al. 2021; Chang et al. 2022). The TPB has also been applied in urban forests to examine individuals’ willingness to pay for urban forest services22,75participation in tree planting programs76,77and governance of green spaces78. However, there hasn’t been a study investigating the factors influencing the behavioral intentions of female high school students regarding conservation of urban forests to mitigate climate change crisis. This paper seeks to bring the exiting gap by exploring these factors.

This theory identifies three independent determinants that predict behavioral intention: attitude, subjective norms (SNs), and PBC. Attitude refers to an individual’s assessment of whether a behavior is desirable or undesirable79. An individual’s attitude is shaped by various factors such as their beliefs about the potential outcomes of a particular behavior and their values80,81,82. In the context of this study, and in alignment with the KAP framework, attitudes are a crucial factor influencing behavioral intentions and subsequent actions83,84. This research emphasizes that attitudes are not solely determined by knowledge but also act as a mediating factor between awareness and the adoption of practices85,86. This underscores the necessity of addressing both cognitive and emotional aspects when developing strategies to encourage behavioral change. Accordingly, this study examines the impact of environmental awareness on attitudes, as well as the influence of environmental awareness and attitudes on behavioral intentions.

SNs as second determinant of intention in TPB, represent the perceived pressure from important people for individuals to either engage in or refrain from behavior. This variable represents the influence of social expectations from significant individuals in a person’s life, encouraging them to either engage in or avoid a specific behavior87. Previous studies have indicated that, in some cases, this factor has a positive and significant impact on behavioral intentions of women of young generation88,89while in other instances, its effect has not been statistically significant90,91. These differences may stem from the role of social dynamics in individual decision-making processes92. Accordingly, this research examines the effect of this variable on the behavioral intentions of female students to combat climate change by participating in the preservation of urban forests. PBC refers to an individual’s confidence in their ability to perform a specific behavior79. It is a key factor influencing behavioral intentions, which serve as the most immediate precursors to behavior93,94. Additionally, PBC can directly predict behavior, particularly when it closely corresponds to the individual’s actual capacity to perform the behavior95. Research further suggests that PBC can influence on attitude toward a behavior95,96. This highlights the critical role of PBC in shaping both intentions and subsequent actions, as it interacts with other psychological factors to influence decision-making processes.

TPB has the capability to incorporate new variables to enhance its explanatory power97. Various studies have successfully added multiple factors, such as personal values98climatic threats to traditional agriculture99environmental awareness33,71perceived risk100and moral norms101,102to the original model, enhancing its explanatory power. In this research Environmental Awareness (EA) and Social Responsibility (SR) were incorporated into basic model to shape extended version of TPB.

EA is defined as an individual’s knowledge about the impact of humans on the environment and acknowledging the importance of environmental protection103,104. Studies suggest that the relationship between behavioral variables related to individuals’ knowledge, such as awareness, and their intentions and behaviors can be complex. Understanding this relationship requires examining both direct and indirect influence105. Studying the impact of EA on pro-environmental behavior has yielded inconsistent results. While some studies suggest that EA is a strong predictor of environmental intention and behavior106,107,108others indicate that it may not reliably predict individuals’ environmental actions109,110. These conflicting outcomes may stem from the direct and indirect pathways through which this variable influences individual’s behavioral intentions. Previous studies have confirmed the impact of this variable on individuals’ attitudes and beliefs regarding various environmental behaviors111,112,113. Since awareness is a form of knowledge86,114therefore in this study, the KAP framework was integrated into TPB to examine not only the direct effect of this variable but also its indirect impact through influencing individuals’ attitudes.

Social responsibility (SR) is another additional variable of extended model that could influence an individual’s intention toward specific behavior. SR is a moral or ethical principle through which individuals feel compelled to engage in a behavior for the collective benefit of their society115,116. Students’ SR and environmental behavior are interconnected concepts that emphasize ethical engagement with society and the environment117. SR serves as a moral foundation for human unity, enabling communities to face challenges such as climate change and advance with courage118can contribute to promoting sustainable development119. Researchers have examined the impact of this variable on young individuals’ behavior, using the TPB. The results have shown that SR positively influences younger generation and students’ behavioral intentions and actions28,31,61,120. Additionally, it has been noted that this variable has a positive impact on the environmental behavior of hikers121. Considering that SR has the potential to evolve into environmental responsibility122ultimately manifesting as environmental intentions and behaviors, this study includes social responsibility as a variable to investigate its impact on students’ environmental intentions.

Based on the variables of the main model as well as the extended model, and considering the potential interactions among these variables, the research hypotheses were formulated as follows:

H1

attitude has significant effect on female high school students’ intention.

H2

The SNs have significant effect on female high school students’ intention.

H3

PBC influences female high school students’ attitude, significantly.

H4

PBC has significant indirect effect on female high school students’ intention.

H5

PBC has significant direct effect on female high school students’ intention.

H6

EA has significant effect on female high school students’ attitude.

H7

EA has significant indirect effect on female high school students’ intention.

H8

EA has significant direct effect on female high school students’ intention.

H9

SR has significant effect on female high school students’ intention.

The research model is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Materials and methods

Study area

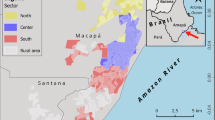

The research was conducted within the city of Khorramabad, Lorestan province, Iran, which spans an area of 600 hectares (Fig. 2). Khorramabad is situated within the forested region of the Zagros Mountains in western Iran. The city hosts 68 hectares of urban forests distributed across three urban zones in Khorramabad123. Khorramabad city consists of three districts that were considered in the sampling approach used in this study. The selected study area, as a rapidly expanding urban center within a developing country, represents a suitable case for advanced research in this field. While women in developing countries often encounter various constraints on their participation in public spaces39,124their engagement in environmental activities has been on the rise125,126. To effectively promote and guide participatory environmental programs, it is crucial to investigate the factors influencing their behavioral intentions. Consequently, this region, with its distinct cultural, social, and climatic characteristics, serves as an exemplary case study for such an investigation.

Study area (A: Iran, B: Lorestan province, C: Khorramabad city): the map was created by authors using ArcGIS 10.6 provided by https://www.esri.com.

Sample size and sampling method

The statistical population of research comprised all female high school students in Khorramabad city. According to the latest data obtained from the Department of Education in Khorramabad, this population was estimated to be around 7,000 individuals. Based on Krejcie & Morgan127, a total of 360 samples were considered sufficient for conducting this study. However, to enhance accuracy, a larger sample size was planned. After excluding incomplete questionnaires, 370 samples were ultimately used for data analysis. The sampling method of stratified sampling with proportional allocation was used128,129. In first step, the sample size was proportionally distributed based on the number of female students in three zone of Khorramabad city. In the second phase, three high schools were selected from each zone, and in the final stage, the sample size within each zone was divided among the three selected high schools, with students chosen randomly from each school. Prior to administering the questionnaire to the students, sufficient explanations about the research and objectives were provided to participants and they were asked to honestly answer the questions. The students were given ample time to read and respond to the questions. Data was gathered during the Jun till September of 2023. The average time for questionnaire filling was 35 min. The questionnaires were completed through face-to-face interviews. Approximately 70% of the students invited to participate in the study accepted the invitation.

Questionnaire design

A questionnaire was designed to collect data (Table 1), consisting of items measuring the variables of the TPB model. The questionnaire included items that corresponded to the three main constructs attitude, PBC, and SNs. Two additional constructs, SR, and EA, along with behavioral intentions. A 5-point scale of Likert was applied to measure the items. The Likert scale was used due to its simplicity for respondents to understand and its widespread application in similar studies130. Prior to the commencement of the study, a two-stage evaluation of the questionnaire was conducted. In the first stage, the questionnaire underwent a thorough review by a panel of experts. A team consisting of various experts including urban forestry, urban planning, climate change, psychology, and high school teachers assessed and confirmed the validity of the questionnaire. Subsequently, the questionnaire was completed by 30 students as a pre-test. The reliability was assessed through the utilization of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient with all value above the standard threshold of 0.7.

Ethical approval and participant consent

This study secured ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committees at Lorestan of Medical Sciences by approval number IR.LUMS.1402.354. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations designated. For the study, explicit written informed consent was obtained from the legal guardians of each student. Moreover, both the guardians and the students were assured that their information and answers to questions would be used exclusively for the purposes of this research without sharing with any other entity.

Data analysis

This study employed a two-step process to ensure the robustness of the measurement model and to test the research hypotheses.

Measurement model evaluation

The first step of data analysis involved assessing the reliability and validity of the measurement model. To ensure internal consistency, reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha (α) and Composite Reliability (CR), both of which are standard metrics for assessing how well the indicators measure their respective latent constructs. A threshold of 0.70 was applied, indicating acceptable internal consistency, as recommended in the literature135,136. In addition, Rho_A was calculated to provide an alternative reliability estimate, offering further validation of construct reliability137. To assess convergent validity, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) was calculated. This measure ensures that each construct captures sufficient variance from its indicators, with an AVE threshold of 0.50 applied to confirm that each construct explains more than half of the variance in its indicators138. Discriminant validity was evaluated using two widely accepted methods: the Fornell & Larcker139 criterion and the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT). The Fornell-Larcker criterion compares the square root of each construct’s AVE with the correlations between constructs, ensuring that a construct shares more variance with its indicators than with other constructs. The HTMT ratio was also employed as a stricter test of discriminant validity. A threshold of 0.85 was used to confirm that the constructs are sufficiently distinct from each other. These combined measures provided a robust evaluation of both the reliability and validity of the measurement model.

Structural equation modeling and hypothesis testing

The second step of the analysis focused on evaluating the structural model and testing the research hypotheses using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). SEM was selected for this study because of its ability to simultaneously estimate multiple relationships between observed and latent variables, as well as assess both measurement and structural models within a single framework138. This approach is particularly suitable for complex models where direct, indirect, and mediating effects need to be analyzed in parallel. The structural model was tested to determine the strength and direction of the hypothesized relationships among the constructs. Path coefficients were calculated to assess the significance of the relationships, and the overall explanatory power of the model was evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R2), which indicates the proportion of variance in the dependent variables explained by the independent variables. A higher R2 suggests that the model has stronger predictive power.

To test the statistical significance of the hypothesized paths, bootstrapping with 5,000 subsamples was performed, a method that provides robust estimates of standard errors and confidence intervals for the path coefficients. This resampling technique allowed for the evaluation of the significance of each path, with t-statistics and P-values used to determine whether the hypothesized relationships were supported by the data. Paths with P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant, indicating strong evidence to support the hypotheses. The data analysis was conducted using SPSS22 for descriptive statistics and preliminary analysis, and Smart-PLS3 software was employed for the SEM analysis.

Results

Reliability and validity

The findings regarding the reliability and validity of the assessment are presented in Table 2. The Cronbach’s alpha values for the model constructs ranged from 0.782 to 0.950, indicating a robust internal consistency across all constructs135. Additionally, the CR values, which measure the reliability of latent variables, were all above the acceptable threshold of 0.70, varying from 0.870 for “Intention” to 0.963 for other constructs. This suggests that the indicators are effectively capturing their intended constructs138. Regarding convergent validity, the AVE values for all constructs exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.50, indicating that each construct accounts for a significant amount of variance in its indicators140. The Rho_A values, which further validate reliability, ranged from 0.809, reinforcing the strength of the measurement model. Overall, these reliability and validity assessments confirm that the constructs are both reliable and valid, ensuring that the measurement model is appropriate for further structural analysis. The discriminant validity of the study model was verified according to the criteria established by Fornell and Larcker (1981), with results displayed in Table 3. The analysis indicated that the square root of the AVE for each construct was greater than the correlations between constructs, demonstrating that each construct explains more variance with its own indicators than with those of other constructs. This result provides strong evidence for discriminant validity, supporting the overall integrity of the measurement model. Further examination of discriminant validity using the HTMT, shown in Table 4, revealed that all HTMT values were below the suggested threshold of 0.85. This confirms that the constructs are sufficiently distinct from one another141. These results strongly indicate that the constructs exhibit significant discriminant validity, thereby enhancing the overall robustness of the measurement model. This thorough validation establishes a solid groundwork for subsequent structural analyses and strengthens the reliability of the study’s conclusions.

Structural models of study

The results of the path analysis for the initial model are depicted in Fig. 3. The results indicated all factor loadings in the model are above 0.7, which is above the acceptable level according to138. The path coefficient results demonstrate that attitude and PBC have positive effects on intention, with values of 0.527 and 0.232, respectively. Furthermore, the constructs of the initial model explain 43.7% of the variance in students’ intention toward engaging in conserving urban forest to combat climate change.

The special model of the research which is extended TPB is shown in Fig. 4 which illustrates the research model with two additional variables. For this model, all factor loadings were above acceptable thresholds. The direct, indirect, and total effects of key constructs of model on behavioral intention are also shown in Table 5. The findings from the developed model revealed that two variables—environmental awareness and perceived behavioral control—account for 26.6% of the variance in students’ attitudes toward urban forest conservation. Furthermore, the model demonstrated an ability to explain 64.9% of the variance in behavioral intentions, reflecting a significant increase of approximately 21% in comparison to the original model of the study.

The findings indicate that attitude (β = 0.285), PBC (β = 0.119), EA (β = 0.354), and SR (β = 0.318) had significant direct effects on intention. Conversely, SNs had a small negative influence on intention (β = -0.063), suggesting that social expectations or pressures may not be a decisive factor in shaping individuals’ willingness to engage in urban forest conservation. In addition to direct effects, the model also accounted for indirect influences. PBC exerted an indirect effect on intention through attitude (β = 0.055), underscoring the role of self-efficacy in shaping positive attitudes toward urban forest conservation intention. Similarly, EA indirectly influences intention via attitude (β = 0.122), reinforcing the idea that increased awareness fosters more favorable attitudes, which in turn translate into stronger behavioral intentions. Notably, the total effect of EA on intention (β = 0.476) was the most substantial among all constructs, highlighting the pivotal role of environmental consciousness in motivating conservation efforts.

The results of hypothesis testing further substantiate these findings (Table 6). Attitude was found to be a strong predictor of intention (H1: p < 0.001), confirming that female high school students with positive attitudes are more likely have stronger intention to engage in urban forest conservation for climate change mitigation. However, the non-significant effect of SNs (H2: p = 0.06) suggests that external social influences, such as societal expectations or peer opinions, may not be sufficient to drive intention. The impact of PBC was twofold. First, it significantly influenced attitude (H3: β = 0.308, p < 0.001), indicating that individuals who perceive greater control over their ability to contribute to conservation efforts tend to develop more favorable attitudes toward such actions. Second, PBC had both a direct (H5: β = 0.191, p < 0.001) and indirect effect (H4: β = 0.099, p < 0.001) on intention, suggesting that individuals who feel capable of engaging in conservation behaviors are more likely to form strong intentions to engage in actual behavior. This highlights the importance of enhancing individuals’ confidence in their ability to participate in conservation initiatives. EA emerged as a key determinant of intention, demonstrating both direct (H8: β = 0.448, p < 0.001) and indirect effects through attitude (H7: β = 0.188, p < 0.001). This suggests that individuals who are more aware of environmental issues are not only more inclined to hold positive attitudes toward conservation but also more likely to translate this awareness into behavioral intentions. Given the strong total effect (β = 0.476), raising EA may be an effective strategy to foster pro-environmental intentions.SR also had a significant direct impact on intention (H9: β = 0.427, p < 0.001), indicating that individuals who perceive conservation as a moral or civic duty are more likely to develop strong intentions to engage in such behaviors. Overall, these results highlight the critical role of EA, attitude, PBC, and SR in shaping individuals’ intentions toward urban forest conservation.

Discussion

This study utilized the extended TPB model to examine the intention of female students to engage in conserving urban forest conservation for combating the effects of climate change. The study aimed to improve the explanatory capability of the initial version of TPB model by including new components, and to examine the influence of these variables on the behavioral intention of female high school students engaged in urban forest conservation for mitigating climate change. The initial model described 43.7% of the variance in students’ intentions. By incorporating two new variables, namely EA and social responsibility, the explanatory capability of the extended model increased to 64.9%. Various studies have confirmed that the incorporating of new components into initial model can enhance the model’s power to explain individuals’ behavioral intentions101,142,143. These two newly introduced variables have demonstrated their effectiveness in explaining a considerable share of the variation of the behavioral intention of female high school students toward the conservation of urban forests to mitigate climate change. The findings underscore the critical role of reinforcing these psychological constructs to effectively enhance the behavioral intentions of female students toward climate change mitigation.

The results confirmed the first hypothesis of study (H1) that attitude influences the intention of students to conserve urban forests to mitigate climate change. This finding aligns with prior research that identifies attitude as a significant variable in determining behavioral intentions of individuals144,145,146,147. A positive attitude as a fundamental determinant of how individuals think and behave97,148,149can lead to actual behavior. This finding highlights the significance of fostering positive attitudes to encourage participation in the conservation of urban forests as a strategy for addressing climate change. Therefore, it is essential to incorporate the development of such positive attitudes into curricula and training programs to facilitate the engagement of female students in this area. The study’s findings indicate that this variable functions as a mediator, channeling the effects of other variables on behavioral intention. Specifically, the results demonstrated that both PBC (H3) and EA (H6) exert a significant and positive influence on this mediator, while attitude serves as the indirect conduit through which these factors affect behavioral intention (H5) and (H7). Although various studies have confirmed the impact of environmental awareness and perceived behavioral control on attitude, a substantial portion of individuals’ attitudes remains unexplained by these variables. This observation underscores the necessity of enhancing awareness and empowering individuals to engage in behavior, as well as the need for further investigation into the factors that shape attitudes toward climate change mitigation.

The second hypothesis of the study rejected influence of SNs on the behavioral intention of female students (H2) to protect urban forests for climate change mitigation. While numerous studies such as Ng (2022), and Zaremohzzabieh et al. (2021) have indicated a significant influence of SNs on individuals’ intentions, this study did not confirm this significant effect. Studies including Jacob et al., (2021); Opdenbosch & Hansson (2023) and Velardi et al., (2023) have similarly reported non-significant or weak effects of SNs on individuals’ behavioral intentions. There could be several reasons explaining our findings. For example, conflicting SNs and cultural differences may weaken the influence of others on students’ behavioral intentions36. Previous research suggests that the effect of SNs on behavioral intention may be moderated by factors such as personal moral norms or descriptive norms150,151. This implies that, in certain contexts, individuals may rely more heavily on internalized moral standards than on perceived social expectations when shaping their behavioral intentions. SNs are often treated as purely cognitive constructs, focusing on social pressure without accounting for emotional factors like anticipated regret or personal significance92,152. This limitation may reduce their predictive power compared to constructs that integrate both emotion and cognition. In this study, it is also possible that the presence of stronger predictors within the model may have diminished the predictive power of subjective norms. Moreover, the important people for students may possess a lack of knowledge about the significance of protecting urban forests for climate change mitigation and it may limit their impact on the behavioral intentions of students to engage in such actions94,153. This is also important in environmental behavior development policy. Awareness raising and educational programs aimed at promoting environmental behaviors should not solely focus on the target group itself but consider individuals who influence the perspectives of the target group.

Our findings confirmed that PBC (H5) influences the behavioral intention of students towards engaging in conservation of urban forest to combat climate change. This variable not only exerted a direct effect on behavioral intention but also demonstrated a significant and positive indirect effect through its influence on attitude (H4). Moreover, it had a significant and positive impact on attitudes (H3). Various research have also supported the positive effect of PBC on intention to engage in a behavior71,154,155. This finding indicates that, although attitude is the primary component in TPB theory, individuals’ perceived ability to perform a behavior plays a significant role in shaping their behavioral intention and can also reinforce their attitude toward that behavior95,96. Therefore, enhancing individuals’ capacity to engage in urban forest conservation may be an effective strategy for strengthening their behavioral intentions. This underscores the necessity of integrating relevant training into both school curricula and the educational programs of urban forest management.

The research findings indicate that EA is the most significant predictor of individuals’ behavioral intentions (H8). In addition to influencing attitudes, this variable demonstrated both direct and indirect effects, exerting the greatest overall impact on attitude (H6) behavioral intention (H7). Numerous studies have emphasized the role of EA in shaping individuals’ intentions toward pro-environmental behaviors104,107,156,157. Moreover, these findings are consistent with the KAP theory, which posits that various types of knowledge can transform into behavior through their impact on attitudes86,112,158. This outcome highlights the critical and multifaceted role of environmental awareness. This suggests that individuals who are more aware of environmental issues are not only more inclined to hold positive attitudes toward conservation but also more likely to translate this awareness into behavioral intentions Therefore, it is imperative to implement environmental awareness programs both within educational curricula and through public promotional initiatives to strengthen individuals’ intentions to engage in forest conservation. Additionally, further research should investigate this variable independently within the framework of the KAP theory to elucidate its effect pathway more clearly.

Our research confirmed the positive and significant impact of SR on the behavioral intention of the students (H9). This variable held the second-highest weight among the determinants of individuals’ intentions, highlighting its significant role in shaping students’ behaviors toward climate change mitigation. Studies have shown that SR is a key factor in promoting pro-environmental behaviors and responses to climate change159,160,161. Therefore, fostering this sense of responsibility among students, as future citizens who will be tasked with addressing climate challenges, is essential. Research indicates that the development of this trait is significantly influenced by both the family and the school environment162,163. Accordingly, it is the shared responsibility of these two institutions to actively contribute to nurturing students’ sense of social responsibility, thereby encouraging them to engage in actions aimed at combating climate change.

Limitations and future research

Despite the valuable and novel insights offered by this study, it is not without limitations, which warrant careful consideration. First, the research was conducted within a specific socio-cultural, climatic, and economic context, which may have influenced the participants’ responses and the overall findings. As such, the generalizability of the results to other contexts should be approached with caution. Future research is encouraged to replicate this study in diverse geographical and socio-cultural settings to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the decision-making mechanisms among female students in relation to climate change mitigation. Second, the study focused exclusively on a single behavioral intention, urban forest conservation. It is plausible that female students’ intentions and behaviors regarding other climate-related actions, such as sustainable consumption or eco-conscious purchasing, may be influenced by different psychological, social, or contextual factors. Therefore, it is recommended that future studies examine the determinants of intention and behavior in a broader range of climate mitigation domains. The theoretical model proposed in this study accounted for approximately 65% of the variance in behavioral intention, indicating a strong explanatory capacity. Nonetheless, the inclusion of additional variables, such as cultural values, religious beliefs, economic constraints, and institutional influences, may further enhance the model’s predictive power and provide a more nuanced understanding of the factors shaping pro-environmental intentions.

It is also suggested that future research employ alternative theoretical frameworks that address other dimensions of behavioral decision-making to validate and expand upon the current findings. Given the significant role of environmental awareness and social responsibility in shaping behavioral intentions, further investigation into the antecedents of these constructs is warranted. A deeper understanding of the drivers behind these psychological factors could inform the development of more effective educational and policy interventions. Furthermore, the study found that EA and PBC contributed to the formation of positive attitudes, which in turn influenced behavioral intention. Considering the central role of attitude in behavioral models, it is recommended that future research explore the underlying factors that shape attitudes toward climate action. The findings of future studies may inform the design of participatory and educational programs aimed at enhancing youth engagement in climate change mitigation. Finaly, examining the broader influence of economic and social variables on the formation of key behavioral constructs presents a valuable direction for future.

Implications

Theorical implications

This study offers significant theoretical contributions to the literature on pro-environmental behavior by extending the TPB to include EA and SR as additional predictors of behavioral intention. The incorporation of these constructs substantially enhanced the explanatory power of the model, which accounted for 64.9% of the variance in students’ intention to engage in urban forest conservation. This finding underscores the theoretical value of contextualizing established behavioral models through the integration of relevant cognitive and normative variables, particularly in domains related to climate change mitigation and environmental stewardship. The significant effects of EA and SR suggest that individuals’ cognitive understanding of environmental issues and their sense of moral obligation toward society play a pivotal role in shaping pro-environmental intentions. These results align with and extend existing theoretical frameworks by highlighting the importance of integrating both rational and normative dimensions into behavioral models. The study also contributes to a more holistic understanding of the antecedents of environmental behavior, especially among youth populations in ecological and socially sensitive contexts. Importantly, the non-significant effect of SNs challenges one of the core tenets of the TPB, the assumption that perceived social pressure is a consistent determinant of behavioral intention. This outcome suggests that, in some socio-cultural settings, internalized values and cognitive awareness may exert a stronger influence on behavioral intentions than external social expectations. This insight calls for a re-evaluation of the universality of TPB constructs and highlights the need for culturally responsive adaptations of behavioral theories. The study demonstrates the necessity of incorporating context-specific psychological and social factors when modeling environmental intentions. Future research is encouraged to further refine theoretical models by exploring additional mediating or moderating variables and by employing cross-cultural comparisons to enhance generalizability. This study also made a significant contribution to the existing body of literature by integrating KAP theory and young women context into the framework of the extended TPB. By doing so, it enhances our understanding of the complex interplay between knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions in the context of environmental conservation among female high school students.

Policy implications

The empirical findings of this study offer several actionable implications for policymakers seeking to enhance youth participation in urban forest conservation as a climate change mitigation strategy. The significant influence of EA and SR on students’ behavioral intentions underscores the necessity of embedding environmental literacy and civic responsibility more systematically within high school education curricula. Educational policies should be reoriented to prioritize experiential and interdisciplinary learning approaches that not only inform students about environmental issues but also cultivate a deeper sense of personal and collective accountability toward ecological preservation. The strong predictive power of EA suggests that when students possess a well-developed understanding of environmental challenges and the functions of urban forests in climate resilience, they are more likely to express intention to engage in conservation activities. Therefore, environmental education policies must move beyond traditional content delivery and adopt pedagogies that facilitate critical thinking, ecological systems understanding, and localized climate solutions. This includes integrating place-based learning modules, school-affiliated conservation programs, and engagement with urban forestry professionals. Moreover, the salient role of SR in shaping behavioral intentions indicates that students’ perceived moral obligations toward society are a powerful motivator of conservation intent. Policymakers should thus consider institutionalizing programs that foster civic environmentalism among youth. This may involve formal recognition of student participation in environmental initiatives, the creation of youth advisory councils on urban greening, and support for peer-led outreach campaigns that normalize pro-environmental behaviors within school and community contexts.

Importantly, the lack of a statistically significant relationship between subjective norms and behavioral intention suggests that relying solely on social pressure or normative messaging may be insufficient in motivating environmental action among adolescents. As such, environmental policies should shift from passive awareness campaigns toward strategies that enhance individual agency and internalized commitment. This calls for the development of policy frameworks that support capacity-building initiatives in schools, including teacher training in sustainability education, provision of resources for student-led environmental projects, and long-term institutional partnerships between educational institutions and urban environmental agencies. These findings point to the need for a more integrative policy approach—one that positions youth not merely as passive recipients of environmental messaging but as active stakeholders in the planning and implementation of urban sustainability efforts.

Conclusions

This study investigated the factors influencing the intention of female high school students to engage in urban forest conservation as a strategy for mitigating climate change. By extending the TPB with the inclusion of EA and SR, the study provided deeper insights into the psychological and social determinants of pro-environmental behavior. The extended model demonstrated a substantial increase in explanatory power, accounting for 65.2% of the variance in students’ behavioral intentions. The findings highlight that attitude, EA, SR, and PBC significantly influence students’ intentions to participate in urban forest conservation. Among these, EA exhibited the strongest effect on intention, reinforcing the notion that increasing students’ understanding of environmental issues can enhance their commitment to conservation efforts. SR also played a crucial role, suggesting that fostering a sense of collective responsibility can encourage engagement in pro-environmental behaviors. In contrast, SNs did not exhibit a significant effect on students’ intentions, aligning with studies that suggest that social influences may be less effective in contexts where awareness and personal commitment drive behavior. These findings carry important implications for environmental education and policy development. Integrating urban forest conservation topics into school curricula, organizing participatory conservation initiatives, and creating community engagement programs can enhance students’ environmental responsibility and perceived control over conservation efforts. Additionally, targeted interventions that strengthen EA and SR among students can significantly boost their willingness to participate in climate change mitigation activities.

Data availability

Data are available on request from corresponding author.

References

Ceranic, G., Krivokapic, N., Šarovic, R. & Živkovi´, P. Perception of Climate Change and Assessment of the Importance of Sustainable Behavior for Their Mitigation: The Example of Montenegro. (2023).

Gomm, X. et al. From climate perceptions to actions: A case study on coffee farms in Ethiopia. Ambio https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-024-01990-0 (2024).

Sargani, G. R. et al. Farm risks, livelihood asset allocation, and adaptation practices in response to climate change: A cross-country analysis. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, (2023).

Tang, Z. et al. Contributions of climate change and urbanization to urban flood hazard changes in China’s 293 major cities since 1980. J. Environ. Manage. 353, 120113 (2024).

Nawrotzki, R. J., Tebeck, M., Harten, S. & Blankenagel, V. Climate change vulnerability hotspots in Costa Rica: constructing a sub-national index. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 13, 473–499 (2023).

Sargani, G. R. et al. No farmer no food, assessing farmers climate change mitigation, and adaptation behaviors in farm production. J. Rural Stud. 100, 103035 (2023).

Aghaloo, K., Sharifi, A., Habibzadeh, N., Ali, T. & Chiu, Y. R. How nature-based solutions can enhance urban resilience to flooding and climate change and provide other co-benefits: A systematic review and taxonomy. Urban Urban Green. 95, 128320 (2024).

Abawiera Wongnaa, C., Amoah Seyram, A. & Babu, S. A systematic review of climate change impacts, adaptation strategies, and policy development in West Africa. Reg. Sustain. 5, 100137 (2024).

Biresselioglu, M. E., Savas, Z. F., Demir, M. H. & Kentmen-Cin, C. Tackling climate change at the City level: insights from lighthouse cities’ climate mitigation e Orts. Front. Psychol. 14, 1308040 (2024).

Aboagye, P. D. & Sharifi, A. Urban climate adaptation and mitigation action plans: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 189, 113886 (2024).

Dharmarathne, G., Waduge, A. O., Bogahawaththa, M., Rathnayake, U. & Meddage, D. P. P. Results in engineering adapting cities to the surge: A comprehensive review of climate-induced urban flooding. Results Eng. 22, 102123 (2024).

Mi, Z. et al. Cities: the core of climate change mitigation. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.10.034 (2018).

Nyashilu, I., Kiunsi, R. & Kyessi, A. Climate change vulnerability assessment in the new urban planning process in Tanzania. Reg. Sustain. 5, 100155 (2024).

Hong, W. et al. Spatiotemporal changes in urban forest carbon sequestration capacity and its potential drivers in an urban agglomeration: implications for urban CO2 emission mitigation under china’s rapid urbanization. Ecol. Indic. 159, 111601 (2024).

Reynolds, H. L. et al. Implications of climate change for managing urban green infrastructure: an indiana, US case study. Clim. Change. 163, 1967–1984 (2020).

Doussard, C. & Delabarre, M. Perceptions of urban green infrastructures for climate change adaptation in lausanne, switzerland: unveiling the role of biodiversity and planting composition. Clim. Change. 176, 1–21 (2023).

Salbitano, F., Borelli, S., Chen, Y. & Conigliaro, M. Guidelines on urban and peri-urban forestry. Fao 170 (2016).

Costemalle, V. B., Candido, H. M. N. & Carvalho, F. A. An Estimation of ecosystem services provided by urban and peri-urban forests: a case study in Juiz de fora, Brazil. Cienc. Rural. 53, 1–9 (2023).

Yadav, H., Iwachido, Y. & Sasaki, T. Effect of urbanisation on feces deposited across natural urban forest fragments. Urban Ecosyst. 27, 2277–2282 (2024).

Guo, Y. et al. Spatiotemporal patterns of urban forest carbon sequestration capacity: implications for urban CO2 emission mitigation during china’s rapid urbanization. Sci. Total Environ. 912, 168781 (2024).

Francini, S. et al. Global Spatial assessment of potential for new peri-urban forests to combat climate change. Nat. Cities. 1, 286–294 (2024).

Maleknia, R. Psychological determinants of citizens’ willingness to pay for ecosystem services in urban forests. Glob Ecol. Conserv. 54, e03052 (2024).

Maleknia, R. Urban forests and public health: analyzing the role of citizen perceptions in their conservation intentions. City Environ. Interact. 26, 100189 (2025).

Ganzevoort, W. & van den Born, R. J. G. Understanding citizens’ action for nature: the profile, motivations and experiences of Dutch nature volunteers. J. Nat. Conserv. 55, (2020).

Morgan, O. S., Coombs, L. M. & Thomas, K. Youth and climate justice: Representations of young people in action for sustainable futures. 1–9 https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12547 (2024).

Palla, A., Pezzagno, M. & Spadaro, I. & Ruggero, E. Participatory approach to planning urban resilience to climate change: Brescia, Genoa, and Matera — three case studies from Italy compared. Sustainability. 16, (2024).

Satinover, B., Holt, J. W. & Nichols & A comparison of sustainability attitudes and intentions across generations and gender: a perspective from U.S. Consumers. Cuad. Gest. 23, 51–62 (2023).

Salguero, R. B., Bogueva, D. & Marinova, D. Australia’s university generation Z and its concerns about climate change. Sustain. Earth Rev. 7, 1–17 (2024).

Diem, H. T. T., Tuori, R. & Thinh, M. P. Cross-cultural insights into youth perceptions of climate change: a comparative study between the US and Vietnam. Comp. J. Comp. Int. Educ. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2025.2452504 (2025).

Tiitta, I., Kopra, J., McDermott-Levy, R., Jaakkola, J. J. K. & Kuosmanen, L. Climate change perceptions among nursing students: A comparative study between Finland and the united States. Nurse Educ. Today. 146, 106541 (2025).

Yu, T. Y., Yu, T. K. & Chao, C. M. Understanding Taiwanese undergraduate students’ pro-environmental behavioral intention towards green products in the fight against climate change. J. Clean. Prod. 161, 390–402 (2017).

Majhi, R. Behavior and perception of younger generation towards green products. J. Public. Aff. 22, (2022).

Ogiemwonyi, O. Factors influencing generation Y green behaviour on green products in nigeria: an application of theory of planned behaviour. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 13, (2022).

Liu, X., Lindhjem, H., Grimsrud, K., Leknes, E. & Tvinnereim, E. Is there a generational shift in preferences for forest carbon sequestration vs. preservation of agricultural landscapes? Clim. Change 176, (2023).

Jama, O. M., Diriye, A. W. & Abdi, A. M. Understanding young people’s perception toward forestation as a strategy to mitigate climate change in a post-conflict developing country. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 25, 4787–4811 (2023).

Salinero, Y., Prayag, G., Gómez-Rico, M. & Molina-Collado, A. Generation Z and pro-sustainable tourism behaviors: internal and external drivers. J. Sustain. Tour. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2134400 (2022).

Phon, P. & Price, R. K. Climate change, forced migration and trafficking in persons: risk of young women in rural Cambodia. J. Hum. Traffick. 10, 361–367 (2024).

Howard, E. Linking gender, climate change and security in the Pacific Islands region: A systematic review. Ambio 52, 518–533 (2023).

Sargani, G. R. et al. How do gender disparities in entrepreneurial aspirations emerge in Pakistan? An approach to mediation and multi-group analysis. PLoS ONE. 16 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260437 (2021).

Peach Brown, H. C. Gender, climate change and REDD + in the congo basin forests of Central Africa. Int. Rev. 13, 163–176 (2011).

Subiza-Pérez, M. et al. Who feels a greater environmental risk? Women, younger adults and pro-environmentally friendly people express higher concerns about a set of environmental exposures. Environ. Res. 181, 108918 (2020).

Vicente-Molina, M. A., Fernández-Sainz, A. & Izagirre-Olaizola, J. Does gender make a difference in pro-environmental behavior? The case of the Basque country university students. J. Clean. Prod. 176, 89–98 (2018).

Sorooshian, S. The sustainable development goals of the united nations: A comparative midterm research review. J. Clean. Prod. 453, 142272 (2024).

Işık, C., Ongan, S., Ozdemir, D., Yan, J. & Demir, O. The sustainable development goals: theory and a holistic evidence from the USA. Gondwana Res. 132, 259–274 (2024).

Deininger, F. et al. Issues and Practice Note Placing Gender Equality At the Center of Climate Action. (2023).

Datey, A., Bali, B., Bhatia, N., Khamrang, L. & Kim, S. M. A gendered lens for building climate resilience: narratives from women in informal work in leh, Ladakh. Gend. Work Organ. 30, 158–176 (2023).

Haque, A. T. M. S., Kumar, L. & Bhullar, N. Gendered perceptions of climate change and agricultural adaptation practices: a systematic review. Clim. Dev. 15, 885–902 (2023).

Hoque, M. & Uddin, M. K. Climate change and adaptation policies in South asia: addressing the gender-specific needs of women. Local. Environ. 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2025.2456549 (2025).

Zeydalinejad, N., Pour-Beyranvand, A., Nassery, H. R. & Ghazi, B. Evaluating climate change impacts on snow cover and karst spring discharge in a data-scarce region: a case study of Iran. Acta Geophys. 73, 831–854 (2024).

Robati, M., Najafgholi, P., Nikoomaram, H. & Vaziri, B. M. Zoning of critical hubs of climate change (flood-drought) using the Hydrologic Engineering Center-Hydrologic Modeling System and copula functions case study: Khorramabad Basin. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-5390435/v1 (2024)

Huggins, C. & Bishwajit, G. Enabling conditions for nature-based solutions for climate adaptation in the Guinean forests of West africa: evidence from Côte d’ivoire, Ghana, and Guinea. J. Environ. Dev. https://doi.org/10.1177/10704965251317450 (2025).

Delpasand, S., Maleknia, R. & Naghavi, H. REDD+ the opportunity for sustainable management in Zagros Forests. J. Sustain. For. https://doi.org/10.1080/10549811.2022.2130359 (2022).

Maleknia, R., Elena Enescu, R. & Salehi, T. Climate change and urban forests: generational differences in women’s perceptions and willingness to participate in conservation efforts. Front. Glob. Chang. 7, (2025).

Acheampong, P. P. et al. Gendered perceptions and adaptations to climate change in ghana: what factors influence the choice of an adaptation strategy? Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7, 1–13 (2023).

Devonald, M., Jones, N., Gebru, I., Yadete, W. & A. & Rethinking climate change through a gender and adolescent lens in Ethiopia. Clim. Dev. 16, 176–186 (2024).

Poortinga, W., Demski, C. & Steentjes, K. Generational differences in climate-related beliefs, risk perceptions and emotions in the UK. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, (2023).

Nikolić, T. M., Paunović, I., Milovanović, M., Lozović, N. & Ðurović, M. Examining generation z’s attitudes, behavior and awareness regarding eco-products: A bayesian approach to confirmatory factor analysis. Sustain. 14, (2022).

Masserini, L., Bini, M. & Difonzo, M. Is generation Z more inclined than generation Y to purchase sustainable clothing?? Soc. Indic. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-024-03328-5 (2024).

Raman, R. et al. The impact of gen z’s pro-environmental behavior on sustainable development goals through tree planting. Sustain. Futur. 8, 100251 (2024).

Aktan, M. & Kethüda, Ö. The role of environmental literacy, psychological distance of climate change, and collectivism on generation z’s collaborative consumption tendency. J. Consum. Behav. 23, 126–140 (2024).

Skeirytė, A., Krikštolaitis, R. & Liobikienė, G. The differences of climate change perception, responsibility and climate-friendly behavior among generations and the main determinants of youth’s climate-friendly actions in the EU. J. Environ. Manag. 323, (2022).

Juma-Michilena, I. J., Ruiz-Molina, M. E., Gil-Saura, I. & Belda-Miquel, S. An analysis of the factors influencing pro-environmental behavioural intentions on climate change in the university community. Econ. Res. Istraz 36, (2023).

Roy, J. et al. Synergies and trade-offs between climate change adaptation options and gender equality: a review of the global literature. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 9, 1–13 (2022).

Ugulu, I., Sahin, M. & Baslar, S. High school students’ environmental attitude: scale development and validation. Int. J. Educ. Sci. 5, 415–424 (2013).

Siagian, N. et al. The effect of environmental citizenship and spiritual norms as mediators on students’ environmental behaviour. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth. 28, (2023).

Cornelia, E. & Erik, G. Ecosystem services from urban forests: the case of Oslomarka, Norway. Ecosyst. Serv. 51, 101358 (2021).

Jones, L., Fletcher, D., Fitch, A., Kuyer, J. & Dickie, I. Economic value of the hot-day cooling provided by urban green and blue space. Urban Urban Green. 93, 128212 (2024).

Smith, B. E. et al. Youths’ investigations of critical urban forestry through multimodal sensemaking. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-024-10127-7 (2024).

Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control: from Cognition To Behavior 11–39 (Springer, (1985).

Popa, B., Niță, M. D. & Hălălișan, A. F. Intentions to engage in forest law enforcement in Romania: An application of the theory of planned behavior. For. Policy Econ. 100, 33–43 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2018.11.005 (2019).

García-Salirrosas, E. E. et al. Influence of environmental awareness on the willingness to pay for green products: an analysis under the application of the theory of planned behavior in the Peruvian market. Front. Psychol. 14, 1282383 (2024).

Xing, H. et al. Public intention to participate in sustainable geohazard mitigation: an empirical study based on an extended theory of planned behavior. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 23, 1529–1547 (2023).

Amare, D., Darr, D. & Amare, D. Farmers’ intentions toward sustained agroforestry adoption: an application of the theory of planned behavior. J. Sustain. For. 00, 1–18 (2022).

Opdenbosch, H. & Hansson, H. Farmers ’ willingness to adopt silvopastoral systems: investigating cattle producers ’ compensation claims and attitudes using a contingent valuation approach. Agrofor. Syst. 97, 133–149 (2023).

López-Mosquera, N., García, T. & Barrena, R. An extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior to predict willingness to pay for the conservation of an urban park. J. Environ. Manag. 135, 91–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.01.019 (2014).

Zhao, Z., Zhang, Y. & Wen, Y. Residents’ support intentions and behaviors regarding urban trees programs: A Structural Equation Modeling-multi group analysis. Sustainability. 10, 10020377. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020377 (2018).

Chiou, C. R., Chan, W. H., Lin, J. C. & Wu, M. S. Understanding public intentions to pay for the conservation of urban trees using the extended theory of planned behavior. Sustain 13, (2021).

Huang, Y., Aguilar, F., Yang, J., Qin, Y. & Wen, Y. Predicting citizens’ participatory behavior in urban green space governance: application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Urban Urban Green. 61, 127110 (2021).

Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behvior Hum. Decis. Process. 50, 179–211 (1991).

Duong, C. D. Cultural values and energy-saving attitude-intention-behavior linkages among urban residents: a serial multiple mediation analysis based on stimulus-organism-response model. Manag Environ. Qual. Int. J. 34, 647–669 (2023).

Maleknia, R., Azizi, R. & Hălălișan, A. F. Developing a specific model to exploring the determinant of individuals’ attitude toward forest conservation. Front. Psychol. 15, (2024).

Stern, P. C., Kalof, L., Dietz, T. & Guagnano, G. A. Values, beliefs, and proenvironmental action: attitude formation toward emergent attitude objects. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 25, 1611–1636 (1995).

Wang, K. & Zhang, L. The impact of ecological civilization theory on university students’ Pro-environmental behavior: an application of Knowledge-Attitude-Practice theoretical model. Front. Psychol. 12, 1–12 (2021).

Zhou, B., Feng, Z., Liu, J., Huang, Z. & Gao, Y. A method to enhance drivers’ hazard perception at night based on knowledge-attitude-practice theory. Accid. Anal. Prev. 200, 107565 (2024).

Salazar, C., Jaime, M., Leiva, M. & González, N. From theory to action: explaining the process of knowledge attitudes and practices regarding the use and disposal of plastic among school children. J. Environ. Psychol 80, (2022).

AlHaddid, O., Ahmad, A. & AbedRabbo, M. Unlocking water sustainability: the role of knowledge, attitudes, and practices among women. J. Clean. Prod. 476, 143697 (2024).

Rivis, A. & Sheeran, P. Descriptive norms as an additional predictor in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Curr. Psychol. 22, 218–233 (2003).

Trelohan, M. Do women engage in pro-environmental behaviours in the public sphere due to social expectations?? The effects of social norm-based persuasive messages. Voluntas 33, 134–148 (2022).

Karimi, S. & Mohammadimehr, S. Socio-psychological antecedents of pro-environmental intentions and behaviors among Iranian rural women: An integrative framework. Front. Environ. Sci. 10 https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.979728 (2022).

D’Arco, M., Marino, V. & Resciniti, R. Exploring the pro-environmental behavioral intention of generation Z in the tourism context: the role of injunctive social norms and personal norms. J. Sustain. Tour 1–22 (2023).

Jacob, J., Valois, P. & Tessier, M. Using the theory of planned behavior to predict the adoption of heat and flood adaptation behaviors by municipal authorities in the province of Quebec, Canada. Sustainability. 13, 1–16 https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052420 (2021).

Maleknia, R., Heindorf, C., Rahimian, M. & Saadatmanesh, R. Do generational differences determine the conservation intention and behavior towards sacred trees?? Trees People. 100591 https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TFP.2024.100591 (2024).

Galván-Mendoza, O., González-Rosales, V. M., Leyva-Hernández, S. N., Arango-Ramírez, P. M. & Velasco-Aulcy, L. Environmental knowledge, perceived behavioral control, and employee green behavior in female employees of small and medium enterprises in ensenada, Baja California. Front. Psychol. 13, 1–19 (2022).

Thuy, P. T., Hue, N. T. & Dat, L. Q. Households’ willingness-to-pay for Mangrove environmental services: evidence from Phu long, Northeast Vietnam. Trees People. 15, 100474 (2024).

Hagger, M. S., Cheung, M. W. L., Ajzen, I. & Hamilton, K. Perceived behavioral control moderating effects in the theory of planned behavior: A meta-analysis. Heal Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0001153 (2022).

La Barbera, F. & Ajzen, I. Control interactions in the theory of planned behavior: rethinking the role of subjective norm. Eur. J. Psychol. 16, 401–417 (2020).

Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychol. Health. 26, 1113–1127 https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2011.613995 (2011).

Sánchez, M., López-Mosquera, N., Lera-López, F. & Faulin, J. An extended planned behavior model to explain the willingness to pay to reduce noise pollution in road transportation. J. Clean. Prod. 177, 144–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.210 (2018).

Tama, R. A. Z. et al. Assessing farmers’ intention towards conservation agriculture by using the extended theory of planned behavior. J. Environ. Manag. 280, (2021).

Savari, M. & Khaleghi, B. Application of the extended theory of planned behavior in predicting the behavioral intentions of Iranian local communities toward forest conservation. Front. Psychol. 14 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1121396 (2023).

Savari, M. & Gharechaee, H. Application of the extended theory of planned behavior to predict Iranian farmers’ intention for safe use of chemical fertilizers. J. Clean. Prod. 263, 121512 (2020).

Chan, H. W., Pong, V. & Tam, K. P. Explaining participation in earth hour: the identity perspective and the theory of planned behavior. Clim. Change. 158, 309–325 (2020).

Kollmuss, A. & Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 8, 239–260 (2002).

Moody-Marshall, R. An investigation of environmental awareness and practice among a sample of undergraduate students in Belize. Environ. Educ. Res. 29, 911–928 (2023).

Wang, Q. et al. The impacts of knowledge and attitude on behavior of antibiotic use for the common cold among the public and identifying the critical behavioral stage: based on an expanding KAP model. BMC Public. Health. 23, 1–13 (2023).

Mohiuddin, M., Al Mamun, A., Syed, F. A., Masud, M. M. & Su, Z. Environmental knowledge, awareness, and business school students’ intentions to purchase green vehicles in emerging countries. Sustain 10, (2018).

Si, W., Jiang, C. & Meng, L. The relationship between environmental awareness, habitat quality, and community residents’ pro-environmental behavior—mediated effects model analysis based on social capital. Int J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19, (2022).

Shen, M. & Wang, J. The impact of pro-environmental awareness components on green consumption behavior: the moderation effect of consumer perceived cost, policy incentives, and face culture. Front. Psychol. 13, 1–13 (2022).

Rampedi, I. T. & Ifegbesan, A. P. Understanding the determinants of pro-environmental behavior among South africans: evidence from a structural equation model. Sustain. 14, (2022).

Liu, P., Teng, M. & Han, C. How does environmental knowledge translate into pro-environmental behaviors? The mediating role of environmental attitudes and behavioral intentions. Sci. Total Environ. 728, 138126 (2020).

Rau, H., Nicolai, S. & Stoll-Kleemann, S. A systematic review to assess the evidence-based effectiveness, content, and success factors of behavior change interventions for enhancing pro-environmental behavior in individuals. Front. Psychol. 13, (2022).

Kousar, S., Afzal, M., Ahmed, F. & Bojnec, Š. Environmental awareness and air quality: the mediating role of environmental protective behaviors. Sustain 14, 1–20 (2022).

Guo, C., Lyu, Y., Li, P. & Kou, I. E. Knowledge attitudes, and practices (KAP) towards climate change among tourists: a systematic review. 1–28 (2025).

Liao, X., Nguyen, T. P. L. & Sasaki, N. Use of the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) model to examine sustainable agriculture in Thailand. Reg. Sustain. 3, 41–52 (2022).

Vu, D. M., Ha, N. T., Ngo, T. V. N., Pham, H. T. & Duong, C. D. Environmental corporate social responsibility initiatives and green purchase intention: an application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Soc. Responsib. J. 18, 1627–1645 (2022).

Agapito, D., Kronenburg, R. & Pinto, P. A review on destination social responsibility: towards a research agenda. Curr. Issues Tour. 26, 554–572 (2023).

Li, X., Liu, Z. & Wuyun, T. Environmental value and pro-environmental behavior among young adults: the mediating role of risk perception and moral anger. Front. Psychol. 13, (2022).

Yi, Y. et al. The mechanism of cumulative ecological risk affecting college students’ sense of social responsibility: the double fugue effect of belief in a just world and empathy. (2023).

Makhdoom, Z. H., Gao, Y., Song, X., Khoso, W. M. & Baloch, Z. A. Linking environmental corporate social responsibility to firm performance: the role of partnership restructure. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 30, 48323–48338 (2023).

Dragolea, L. L. et al. Determining factors in shaping the sustainable behavior of the generation Z consumer. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, (2023).

Zarei, I., Ehsani, M., Moghimehfar, F. & Aroufzad, S. Predicting mountain hikers’ pro-environmental behavioral intention: an extension to the theory of planned behavior. J. Park Recreat Admi. 39, 70–90 (2021).

Begum, A. et al. evaluating the impact of environmental education on ecologically friendly behavior of university students in Pakistan: the roles of environmental responsibility and Islamic values. (2021).

Hoshyari, Z., Maleknia, R., Naghavi, H. & Barazmand, S. Studying Spatial distribution of urban parks of Khoramabad City using network analysis and buffering analysis. J. Wood Sci. Technol. 27, 37–51 (2020).

Ntamack, S. A. S. & Song, J. S. Does climate change hinder women’s participation in the labour market in africa?? Nat. Resour. Forum. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-8947.12601 (2025).

Humayra, J., Uddin, M. K. & Pushpo, N. Y. Deficiencies of women’s participation in climate governance and sustainable development challenges in Bangladesh. Sustain. Dev. 32, 7096–7113 (2024).

Aziz, N., Baber, J., Raza, A. & He, J. Feminist-environment nexus: a case study on women’s perceptions toward the China-Pakistan economic corridor and their role in improving the environment. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 68, 363–385 (2025).

Krejcie, R. V. & Morgan, D. W. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 30, 607–610 (1970).

Neyman, J. On the two different aspects of the representative method: the method of stratified sampling and the method of purposive selection. J. R Stat. Soc. 97, 558 (1934).

Sedgwick, P. Stratified cluster sampling. BMJ 347, f7016–f7016 (2013).

Joshi, A., Kale, S., Chandel, S. & Pal, D. Likert scale: explored and explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 7, 396–403 (2015).

Zhong, F. et al. Quantifying the influence path of water conservation awareness on water-saving irrigation behavior based on the theory of planned behavior and structural equation modeling: A case study from Northwest China. Sustainability. 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184967 (2019).

Fenitra, R. M., Tanti, H., Gancar, C. P., Indrianawati, U. & Hartini, S. Extended theory of planned behavior to explain environmentally responsible behavior in contex of nature-based tourism. Geojournal Tour. Geosites 39, 1507–1516 https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.394spl22-795 (2021).

Ng, S. L. Effects of risk perception on disaster preparedness toward typhoons: an application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 13, 100–113 (2022).

Gansser, O. A. & Reich, C. S. Influence of the new ecological paradigm (NEP) and environmental concerns on pro-environmental behavioral intention based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB). J. Clean. Prod. 382, 134629 (2023).

Cronbach, L. J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16, 297–334 (1951).

Hair, J., Hault, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sardtedt, M. & Thiele, K. O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. Ournal Acad. Mark. Sci. 45, 616–632 (2017).

Chamcham, J., Pakravan-Charvadeh, M. R., Maleknia, R. & Flora, C. Media literacy and its role in promoting sustainable food consumption practices. Sci. Rep. 14, 18831 (2024).

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M. & Ringle, C. M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 31, 2–24 (2019).

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50 (1981).

Hair, J. & Alamer, A. Research methods in applied linguistics partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in second Language and education research: guidelines using an applied example. Res. Methods Appl. Linguist. 1, 100027 (2022).

Dijkstra, T. K. & Henseler, J. Consistent and asymptotically normal PLS estimators for linear structural equations. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 81, 10–23 (2015).

Tan, Y. et al. Residents’ willingness to engage in carbon generalized system of preferences - A personality insight study based on the extended theory of planned behavior. J. Environ. Manage. 361, 121224 (2024).

Maleknia, R. & ChamCham, J. Participatory intention and behavior towards riparian peri-urban forests management; an extended theory of planned behavior application. Front. Psychol. 15, 13723545 (2024).

Ullah, S. M. A., Tani, M., Tsuchiya, J., Rahman, M. A. & Moriyama, M. Land use policy impact of protected areas and co-management on forest cover: A case study from Teknaf wildlife sanctuary, Bangladesh. Land. Use Policy. 113, 105932 (2022).

Velardi, S., Leahy, J., Collum, K., McGuire, J. & Ladenheim, M. Size and scope decisions of Maine maple syrup producers: A qualitative application of theory of planned behavior. Trees People. 12, 100403 (2023).

Amare, D. & Darr, D. Farmers’ intentions toward sustained agroforestry adoption: an application of the theory of planned behavior. J. Sustain. For. 42, 869–886 (2023).

Sargani, G. R., Zhou, D., Raza, M. H. & Wei, Y. Sustainable entrepreneurship in the agriculture sector: the nexus of the triple bottom line measurement approach. Sustain 12, 1–24 (2020).

Harland, P., Staats, H. & Wilke, H. A. M. Explaining proenvironmental intention and behavior by personal norms and the theory of planned behavior 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 29, 2505–2528 (1999).

Maleknia, R. Roots of urban forest conservation behaviors: discovering determinants of citizens’ attitudes. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 26, 100671 (2025).

Bae, T. J., Lee, C. K., Lee, Y., McKelvie, A. & Lee, W. J. Descriptive norms and entrepreneurial intentions: the mediating role of anticipated inaction regret. Front. Psychol. 14, (2024).

Sia, S. K. & Jose, A. Attitude and subjective norm as personal moral obligation mediated predictors of intention to build eco-friendly house. Manag Environ. Qual. Int. J. 30, 678–694 (2019).

Liu, Y., Farris, K. B., Nayakankuppam, D. & Doucette, W. R. Establishing the approach of norm balance toward intention prediction across six behaviors under the theory of planned behavior. Pharmacy 11, 67 (2023).