Abstract

Magnesium alloys are being explored as biodegradable metal alloys for implant applications because of their analogous engineering properties with human bones such as Young’s modulus and density. Conventional machining of biodegradable Mg alloys is challenging due to low melting point (650 °C), occurrence of chatter, built-up edge (BUE) formation, poor surface finish, and low dimensional accuracies. Among non-conventional machining methods, Electric Discharge machining (EDM) is the most popular material removal technique because of its ability to handle the temperature issues related to Mg alloys due to the presence of dielectric and can generate 3D complicated intricate shapes with tighter tolerances. In addition, the powder-mixed variant of the EDM process possesses the unique capability of producing machined surfaces comprising of oxides and carbides which in turn improves the biocompatibility of metallic implants. Moreover, EDMed surfaces have greater hardness and better wear and corrosion resistance. In the current work, Mg-WE43 alloy was machined via die-sinking EDM process by varying SiC powder concentrations (Cp) (2, 4, 6 g/l) together with the variation in pulse current (5, 7, and 9 A) and pulse-on-time (50, 75 and 100 µs). To understand the surface characterization, machined surfaces were examined by measuring the surface roughness and re-cast layer thickness as output responses. Furthermore, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) were used to analyze the formation of oxides and carbides on the machined surfaces. A minimum surface roughness of 2.70 μm was obtained at 2 g/l powder particle concentration (Cp), 50 µs pulse-on-time (Ton), and 7 A pulse current (Ip) with a re-cast layer thickness (RLT) of 31.318 μm while a minimum recast layer of thickness 28.20 μm was produced at 4 g/1 powder Cp, 5 A Ip, and 50 µs Ton with Ra value of 3 μm. SEM analysis of machined workpieces of both tests revealed shallow craters and smooth surfaces with a uniform distribution of carbides. The latter phenomenon was also confirmed by Energy Dispersive Analysis (EDS) executed on machined surfaces.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Implants are considered a potential solution for the survival of human life. Implant installation can be long-term or short-term. There are two types of implants. One type is Non-biodegradable implants which support or replace the missing body parts permanently . Dental implants, bone plates, heart pacemakers, and joint replacements are examples of few non-biodegradable implants1. If the presence of implants is required on a short-term basis, then non-biodegradable implants are not the preferred choice as the said implants exhibit greater Young’s modulus (200 GPa.) and greater density in comparison to human bones and hence can produce adverse effects, that is why detachment of such implants are necessary after a certain time2. Stainless steel (SS)3Ti-based alloy4and Co-based alloy5 are examples of non-biodegradable implants. Stainless implants are ten times stiffer in comparison to human bones which in turn causes bone resorption due to stress shielding3. Substantial differences between the Ti-alloy implant composition and human bone lead to weak osseointegration and chemical bone bonding4. In Co-based alloys, high nickel content leads to allergic reactions with the host tissues as well as low biocompatibility5. All these aforementioned non-degradable implants possess high inflammation risk and toxicity, hence the removal of implants is sometimes inevitable but the elimination requires another surgery which has its side effects and chances of failure. In addition, patients are also found to be tense due to second surgery thoughts so to avoid all these adversities, researchers discovered capable substitutes, termed as bio-degradable implants which can avoid post-surgical hazards1. In this context, magnesium (Mg) and its alloys emerged as potential alternatives. Mg alloys are non-toxic and dissolve in the human body environment in the presence of water, protein, and acid. Moreover, the elastic properties of Mg alloys such as density (1.75 g/cm3) are similar to human bone. Screws, bone plates, and pins are few examples of degradable implants6. Mg alloys have attracted much attention from the field of orthopedic implants and tissue engineering due to their capability of enhanced cell simulation, good biocompatibility and faster bone formation but early degradation of these alloys is quite challenging as if biodegradation occurs before diseased tissue recovery then it is considered as implant failure7. One possible remedy to handle this issue is the alloying of Mg with adequate alloying elements. On the other hand, various chemical, mechanical, biological, and physical coatings were recommended to delay this degradation problem8. Additionally, AI techniques are now being used widely by scientists to detect various fractures and misalignments in the human body as well as in other biomedical sectors9–]13.

The limitation of these techniques is that despite producing a bioactive surface they still need the manufacturing of the implant to happen separately as these procedures only coat the interacting surface of the implant. All manufacturing techniques produce considerable porosity and surface roughness issues as well as the aforementioned post-processing techniques for coating surfaces, which result in increased workload and enhanced cost for manufacturing14. Fabrication of implant requires material removal processes but conventional machining of all Mg alloys is challenging due to several issues such as low melting point (650 oC), the occurrence of chatter, built-up-edges (BUEs), poor surface finish and lower dimensional accuracies and geometric precision15. Among non-conventional machining processes, Electric Discharge Machining (EDM) was proposed in ref15. as a potential technique to machine Mg alloys with greater precision and improve biocompatibility. Furthermore, dielectric was found to handle the temperature-related issues associated with the said alloys, and the Mg alloy parts were machined with greater dimensional tolerances. To shape the material while simultaneously producing complex and intricate shapes is the unique capability of the EDM process16,17. EDM was suggested as an established surface modification process by Kumar et al.18 However, sudden temperature rise followed by abrupt cooling causes the solidification of unflushed melted material on the workpiece surface in the form of a recast layer. Non-uniform recast layer thickness and the presence of micro-cracks reduce the implant’s capability to resist corrosion and abrasion, hence leading to implant failure. In this context, researchers tried various modifications in the commonly employed EDM processes. Recently, Davis et al.19 worked on surface modification of Mg AZ91D alloy while using cryogenically treated (CT) brass and copper tool electrodes. The performance of CT electrodes was compared with untreated electrodes with the former outperforming the latter counterparts. The surface machined via CT copper electrodes showed minimum micro-cracks and craters, improved microhardness (17.45%), acceptable surface roughness (1.8 μm-Ra), adequate recast layer thickness (2.69 μm), and suitable hydrophobic behavior which in turn confirmed the desired biodegradation rate. Powder mixed variant of the EDM process is another emerging and promising area to modify the surface of biocompatible plants in general20 and Mg AZ91D biodegradable alloy in particular21,22. Powder particle (Pp) concentrations of Zn at various levels (0 to 8 g/l) were evaluated and optimization of this input variable was suggested as the key parameter for surface modification of AZ91D Mg alloy. Powder concentration at 4 g/l resulted in uniform recast layer thickness (29.73 μm), shallow craters, and the formation of Zn and Mg oxides on the machined surface. The latter factor delays the faster degradation of biodegradable implants.

WE43 alloy is another casted and biodegradable Mg alloy but data on the machining of this alloy is limited. Klocke et al.15 investigated the geometrical accuracy, surface roughness, and resulting surface integrity (SEM, EDX) of WE43 Mg alloy machined by wire EDM. Using one rough cut followed by four trim cuts, the existence of a recast layer was not found however in vivo and in vitro testing was recommended by the authors to prove the capability of the EDM process suitable for the said alloy. In another study, Klocke et al.23 employed wire and sinking Electro Discharge Machining for surface modification of WE43 Mg alloy. SEM & EDX analysis was used to study the surface properties like complex micro- and macrostructures. They compared stainless steel wire with brass wire in wire-EDM and found no disparity in the performance of both wires. With die-sinking EDM, except for carbon, no element was found on the surface. They evaluated toxicity by In-vitro test (DIN EN ISO 10993-5) and concluded slight toxicity of machined magnesium surface which could be resolved with optimized process parameters as suggested by the authors. Even though WE43 Mg alloy has extensive applications in plates and screws24literature entailing an in-depth study on surface characterization of WE43 alloy via EDM process is still lacking. Additionally, to further improve the surface properties and to reduce the aggressive degradation problem commonly associated with Mg alloys, a powder-mixed variant of this process is selected.

Table 1 is provided in this section which summarizes the type of alloy and corresponding surface characterization techniques together with various In-vivo and In-vitro testing details.

Materials and methods

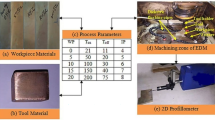

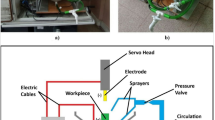

Biodegradable magnesium alloy (WE43) was used as workpiece material which was available in the form of a plate having dimensions of 200 × 200 × 10 mm (length × width × thickness). The workpiece was imported from Suzhou Chuanmao Metal Materials Co. Ltd. China. Experimentation was executed via a Cu electrode (15.9 mm) using kerosene oil as a dielectric (mechanism shown in Fig. 1). In the human body, Copper (Cu) is a requisite trace element and a vital constituent & catalytic agent of numerous proteins and enzymes. Biomaterials comprised of Cu have exceptional healing & antibacterial effects along with shielding the cardiovascular system36. Moreover, the Cu electrode was preferred over the brass electrode in refs19,21,22. in EDM machining of AZ91D Mg alloy therefore chosen herein as electrode material. Kerosene oil was used as it can handle the temperature-related issues of Mg alloys15. In addition, kerosene oil provided better surface quality and material removal rate than deionized water and has a greater tendency for carbide formation37. Powder-mixed electric discharge machining (PMEDM) produced better functional and modified implant surfaces as opposed to the commonly employed EDM process, therefore this EDM variant is selected16. Previously, Zn and Cu powders were used in EDM of Mg alloys21,22 while encouraging results were obtained with SiC powders on Titanium alloys34,35 therefore a need is felt that SiC powders should be evaluated on WE43 Mg alloy. Silicon Carbide (SiC) powder with a mesh size of 14–20 (≈ 841 microns average) was used. There is a consensus in the literature that powder particle concentration (PPCs) must be optimized for a given tool-workpiece combination1,22,34,35 as low PPC resulted in poor machinability due to weak bridging effect and high PPC led to short-circuiting. The PPC variable was considered the most impactful parameter for surface modifications of biomedical implants, therefore few preliminary trials were conducted to select the levels of PPC i-e 2, 4, and 6 g/l. A separate system for mixing SiC powder was integrated with an EDM machine (Model: Rj-230 by Creator, Taiwan). A motorized stirrer was coupled with a pump in a separate tank for machining with negative polarity as visible from the setup in Fig. 2. Current and Pulse duration were found to produce a noticeable impact on output responses including material removal rate, surface roughness, and recast layers thickness in powder mixed EDM process for surface modifications in refs21,34,35,38,39. hence selected here as input variables. Again as mentioned earlier, some pilot trials were conducted to select the levels of these input variables.

Experimental setup details34.

The list and level of input variables are given in Table 2. Additionally, nine more experiments (full-factorial design – 3 levels of current and 3 levels of pulse duration) were conducted without powders to compare results with the powder-mixed EDM process. Roughness meter (manufactured by Taylor Hobson, UK) was employed for measuring the workpiece surface roughness of machined samples and an average of three Ra values was used. The topological analysis of machined surfaces was executed through Field Electron and Ion (FEI) inspect S50 SEM and the re-solidified layers were examined on an OLYMPUS STM6-LM microscope. After dissecting the samples with CNC wire-cut, the surfaces were sanded using 400–2000 mesh size emery paper and polished with 0.5-1 diamond paste before etching using Etchant 120 (10 ml HF, 90 ml Water) as per ASTM, E 407 standard.

Results and discussion

Table 3 shows the full factorial design wherein 27 experiments were conducted. Additionally, nine more experiments that were conducted without powders are also shown in Table 4. The current study looks at the surface characteristics including surface roughness (SR), recast layer thickness (RLT), surface cracks, porosity, and surface chemistry that are essential for improving biocompatibility, adhesion, and osseointegration. With Powder mixed EDM process, a minimum Ra of 2.70 μm was achieved in Test 5 (Ip = 7 A, Ton = 50 µs, Cp = 2 g/L) while its maximum value of 10.30 μm-Ra was achieved in Trial 8 (Ip = 7 A, Ton = 50 µs, Cp = 6 g/L). In the case of the EDM process, performed without powders (termed as commonly employed EDM process and abbreviated as CEDM), the minimum surface roughness of 4.10 μm resulted in Test 1 (Ip = 7 A, Ton = 50 µs) and a maximum of 13.07 μm for Experiment 8 (Ip = 9 A, Ton = 75 µs). A comparison of Test 5 of PMEDM with Test 1 of CEDM demonstrates approximately 51% higher Ra value with the latter as the only difference between these two tests is the presence of powder particles. On the same analogy, Test 8 of PMEDM was compared with Test 8 of CEDM and a 27% higher Ra value was observed with the latter test. This comparison indicates that powder-mixed EDM is quite beneficial over CEDM in terms of producing low SR results. Similar results were reported by Umar et al.34 and Mughal et al.35 in the PMEDM process.

The main effect plots of PMEDM are shown in Fig. 3 and indicates that an increase in current from 5 A to 9 A produced a more rough surface while powder concentration (Cp) and Pulse duration (Ton) showed a quadratic relationship relative to SR. Cp & Ton produced the least SR at their level 1 i.e. 2 g/L & 50 µs. When Cp & Ton were escalated to level 2 i.e. 4 g/L & 75 µs, the maximum value of SR was produced while with level 3 of both the input variables (6 g/L & 100 µs), a reduction in Ra value was noticed in comparison to the values obtained at level 2 parameters. An increase in Pulse current developed a high spark energy which caused immense melting and in turn, more damage to the surface due to larger and deeper craters contributed to higher surface roughness. Similar results were observed in Ti-6Al-4 V EDM machining with SiC powder additives34. For powder concentration, the Ra value was lowest at Cp = 2 g/L which then escalated to its maximum value at Cp = 4 g/L followed by a decline at Cp = 6 g/L. The trend mentioned above can be explained by the fact that at 2 g/l Cp, the spark traveled via powder particles and struck the machined surface with the desired intensity likely due to an effective bridging effect between tool-workpiece electrodes, resulting in shallow and small craters, hence lowest Ra value. Furthermore, an increase in Cp to 4 g/l produced an increase in Ra value possibly because the spark traveled via powders but could not hit the machined surface with good intensity leading to unbalanced energy distributions and the formation of ridges and craters. All these factors contributed to higher Ra value. Further increase in Cp value from 4 g/l to 6 g/l decreased the Ra value and was likely due to the presence of evenly dispersed carbon sediments, powder particles, and debris which in turn produced a homogeneous distribution of spark energy. The SR was lowest at 50 µs due to low discharge energy causing lesser deposition of molten material and less surface damage. The escalation in the value of SR at 75 µs was possibly due to poor flushing of debris between tool and workpiece space during that duration which allowed more crater formation and redepositing of material, hence high surface roughness. The 100 µs pulse on time likely allowed steady re-deposition of removed material from the machined surface to produce a smoother surface than 75 µs.

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) highlights the statistical significance of all interactions. Interaction plots are shown in Fig. 4. Figure 4 (a) shows the interaction between pulse current and pulse on time. At 5 A & 9 A current, the trend of pulse on time relative to surface roughness is somewhat similar to the main effect plots explained earlier in the previous paragraph. However, the opposite is true for 7 A where the surface roughness is maximum at level 1 of pulse on time. With the increase in Ton, a reduction in Ra value was observed. While machining at level 3 of 7 A current, a marginal rise in Ra was noticed relative to level 2 of pulse on time. Figure 4 (b) shows the interaction between Cp and Current. The current at levels of 5 A and 9 A produced the same trend seen in main effects plots of powder concentrations, however 7 A current produced a different trend, generating the same Ra value at 2 g/l and 4 g/l Cp while a steep increase in Ra was noticed at 6 g/l Cp which was likely due to more deposition of powder particles and debris in the craters, causing inefficient flushing and in turn short-circuiting. Figure 4 (c) shows the interaction between Pulse on time and Cp. Pulse on time at 75 & 100 µs have same trend relative to SR as that of main effect plot of Pulse on time. Pulse on time of 50 µs pulse shows the reverse trend compared to what was seen with 75 and 100 µs wherein SR increases linearly with powder concentration. This can be attributed to the amount of available time being insufficient for removal of particles to escape between the electrode gaps. Ehsan et al.40 explored the effects of flushing attributes on the machining performance and highlighted the significance of pulse on time to melt the material and pulse off time to flush material away. It can be assumed that with the increase in powder concentration, the particles occupied the electrodes gap was also increased hence 50 µs pulse on time was inadequate for homogeneous deposition of particles on machined surface. The representative Analysis of variance of surface roughness of PMEDM samples are as presented in Table 5. It is evident that the interaction between I and Ton; I and Cp as well as Ton and Cp showed a significant level of interactions.

As per Table 3, the minimum SR was achieved in Test 5, and the maximum SR was recorded in Trial 8. Figure 5 is the SEM image of both these samples. Experiment 5 produced a smooth surface with rather shallow depressions/craters and a uniform distribution of SiC visible as white spots, see Fig. 5 (a). On the contrary, Fig. 5 (b) shows more re-deposition of melted material causing unevenness on the surface, hence higher Ra value.

Figure 6 shows SEM images of Tests 8 and 14 at greater magnification where the former test produced rougher surfaces which are quite evident in the presence of greater deposition of re-melted material, however, the surface is quite smooth in Test 14. The effect of powder concentrations and higher current notably deteriorated the surface quality in the former test. Optical metallographic images of cross-sections of machined samples denote the penetration of energy into the base material. Darker regions denote that the material was more exposed to the discharge energy of sparks. More current means more discharge energy per spark for unit time hence a thicker heat-affected zone (HAZ). Considering the physical properties of magnesium alloy, the low magnitude of pulse current and pulse on time produced low energy transfer and effective heat conduction through the material.

Experiment Test 5 of PMEDM produced the lowest SR of 2.70 μm-Ra with the following parameters: 7 A, 2 g/L & 50 µs while Test 8 of PMEDM produced 10.30 μm-Ra while operating at parameters: 7 A, 6 g/l & 50 µs. Figures 7 (a) and (b) show the SEM images at 250x and 1000x magnification of Test 8 of PMEDM. Deep craters and random distribution of carbides are quite apparent, so the surface roughness is quite high. In Figs. 7 (c) and (d), carbides are uniformly distributed and craters are quite shallow, hence better surface finish was obtained at these parameters. Figures 7 (e) and (f) show the surface generation in the EDM process performed without powders. Carbides that are visible in Figs. 7 (a) to (d) are not seen here, rather much more re-melted material and craters are quite obvious, contributing to higher Ra value.

Figures 8 (a) and (b) show the SEM images at 500x magnification of Test 8 of CEDM and Test 20 of PMEDM respectively. In the former figure, cavities and a much larger content of re-melted material are quite obvious, resulting in a higher Ra value of 13.07 m. Additionally, no evidence of white spots formed as a result of carbide formation is visible. Contrarily, a smooth region (without any cavity/crater) is noticed together with the occurrence of carbides and a surface value of 3.70 μm-Ra.

Figure 9 (a) shows the SEM image of Test 14 of PMEDM. Smooth regions are quite apparent together with the occurrence of carbides. The surface roughness value is 3.00 μm-Ra. However, Fig. 9 (b) rather shows uneven size of carbides and in-abundant re-melted material deposited on the machined surface producing a maximum Ra value of 10.30 μm.

Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) was performed to explore the fact that the surface is produced with suitable morphology and has a credible chemistry/composition for biocompatibility. Test 5 of PMEDM with the parameter set of 7 A, 2 g/L & 50 µs produced the least Ra-value. EDS analysis at two spots (spot 1 and spot 3) of its top surface is depicted in Fig. 10. The top view is more helpful in understanding the presence of Si, oxygen, and carbon deposition. The presence of Si correlates with the SiC powder deposition onto the machined surface, while the incidence of oxygen affirms the existence of oxides. The presence of oxides and carbides on the machined surface indicates better bioactivity, resistance to corrosion, and antibacterial characteristics as mentioned by Davis et al.22. Oxides of Si act as a bio-passive layer and have more capability of retaining ions and complementing the biocompatibility of surfaces. For the same sample, the SEM image of the side and corresponding EDS (spot 1) is visible in Fig. 11. It is important to mention that side images were taken in proximity to the edge to make sure that constituents of the machined layer could be detected, as highlighted in ref41.

The material removal from the gap is dependent on the flushing speed. Still, even then a certain amount of molten material remains in the gap and gets deposited back onto the substrate surface. This re-deposition is unavoidable however layer thickness can be controlled by optimizing the machining conditions. This redeposited molten metal exhibits a white appearance under optical microscopy hence termed as white layer. Implants could suffer detachment or inflammation from host tissues if re-cast layer thickness (RLT) is beyond a certain depth. RLT thickness is desired to be minimal for better performance in the application as reduced thickness possesses lesser cracks and greater abrasion resistance42. Considering the trend in the literature, SEM/EDS analysis and Ra values of the EDMed surfaces are of utmost importance when the surface is being investigated for possible biomedical implant applications. Minimum surface roughness has been considered the principal requirement of a suitable bioactive surface as per reviews presented by Davis et al.1 and Thanigaviel et al.43. After measuring the Ra value which determines the implant surface interaction with host tissues and cells, the samples of Tests 5, 8, 14, and 20 of PMEDM from Table 3 and Tests 1 & 8 of CEDM from Table 4 are selected for further investigation for RLT evaluation.

For PMEDM, Tests 5, 8, and 14 produced 31.3 μm, 37.4 μm 28.21 μm RLT respectively while RLT for Test 20 was 43.37 μm. For CEDM, Tests 1 and 8 generated 17.48 μm and 27.60 μm RLT. Considering the physical setup experimentation which was kept the same at the volumetric level, PMEDM had more particles occupying the same amount of space in comparison to CEDM. This eventually led to the deposition of more particles onto the machined surface while CEDM only removed debris. More concentration of suspended powder was responsible for a thicker recast layer. The mechanism associated with powder-mixed electric discharge machining is shown in Fig. 12, though taken from the ref34. for explanation purposes and demonstrate the PMEDM process excellently. The suspended powder acts as a bridge to break down the electric arc and reduce the depth of energy penetration44.

Schematic illustration of PMEDM process (a) without powder and (b) with powder34.

Figure 13 demonstrates the increase in recast layer thickness with the increase in SiC powder concentrations. The RLT was maximum in Test 20 and minimum in Test 14, the only difference between these two tests is powder concentration. The former was performed at 2 g/l and the latter was conducted at 4 g/l. It is thought that less powder was able to block less discharge energy and allowed more to pass it through the dielectric and penetrate the surface, resulting in a thicker recast layer. However, 4 g/L powder concentration was able to disperse the discharge energy most efficiently compared to 2 g/L hence less energy penetrated the machined surface and in turn, produced a thin recast layer of 28.20 μm. With the provision of the same Ton, more discharge energy is available to the dielectric with the increase in Pulse current, hence thicker recast layers were produced in Tests 8 and 5 of PMEDM (7 A) in comparison to Tests 14 and 20 (5 A) see Fig. 14. Test 8 generated a 20% thicker re-cast layer as compared to Test 5 likely due to improper flushing of powders and short-circuiting associated with a greater powder concentration of 6 g/l which contributed greater material re-deposition, as mentioned earlier in the section where the main effects plots were explained.

The main effects plots of Table 4 for SR are shown in Fig. 15 and the ANOVA analysis is in Table 6. Pulse current is significant and shows a quadratic relationship relative to surface roughness (SR). The roughness value was minimum at 7 A current level as opposed to 5 A and 9 A current. This was possibly due to the comprehensive ionization of the dielectric medium producing a rather even dispersion of energy and a smoother surface. Test 1 of CEDM produced 4.10 μm-Ra with the following parameters: 7 A & 50 µs and a minimum RLT of 17.487 μm while Test 8 of CEDM produced 13.07 μm-Ra with the following parameters: 9 A & 75 µs together with a RLT of 27.603 μm.

Figure 16 shows the EDS analysis of experiment 8 of CEDM and it is quite obvious that SiC particles were not detected however a surface rich in base material i.e. magnesium and traces of carbon and oxygen from the decomposition of dielectric are also present.

Figure 17 shows the summary of Ra and RLT values for tests conducted without powders (Tests 1 and 8) and with powders (Tests 5, 8, 14, and 20). In terms of low Ra and minimum RLT value, Tests 5 and 14 of PMEDM are recommended to produce good bio-compatible machined surface as evident from the from the formation of oxides and carbides.

Conclusions

The current study evaluated the machinability of biodegradable magnesium Mg WE-43 alloy machined via Die-sinking EDM process by varying SiC powder concentration (2, 4, and 6), Pulse duration (50 µs, 75 µs, and 100 µs) and Pulse current (5 A, 7 A, and 9 A).

Surface characterization involving surface roughness, recast layer thickness, SEM, and EDS analysis was performed on the machined surface. The following conclusions are drawn;

-

The PMEDM process generally produced better surface roughness than the EDM process, which was conducted without powders.

-

Two tests of PMEDM were optimized and recommended to produce machined surfaces with acceptable surface roughness, lower RLT, and a good biocompatible surface. The details of these two tests are given below:

-

Test 5 of PMEDM at the parametric setting of 7 A, 50 µs, and 2 g/l produced the lowest 2.70 μm-Ra and 31.38 μm-RLT while Test 14 of PMEDM at the parametric setting of 5 A, 50 µs and 4 g/l generated 3.00 μm-Ra and least RLT of 28.21 μm.

-

SEM analysis of Test 5 of PMEDM showed shallow craters and uniform distribution of carbides while smooth regions and fewer craters were seen in Test 14 of PMEDM. The EDS analysis further confirmed the presence of carbides and oxides which indicated the biocompatibility of the machined surface.

-

Test 8 of PMEDM at 7 A, 50 µs, and 6 Cp revealed maximum surface roughness (10.30 μm-Ra), the highest RLT (37.456 μm), uneven size carbides dispersion and greater deposition of re-melted material, hence incompatible machined surface.

Limitations and future work

The current study is restricted to the evaluation of roughness, measurement of recast layer thickness, SEM and EDS analysis of machined surface. To further investigate the surface modifications of machined surfaces produced at the optimized settings (Tests 5 and 14 of PMEDM), microhardness, corrosion resistance, and wettability will be studied in our future work to substantiate the claim. Though Tests 5 and 14 of PMEDM are recommended, a more comprehensive in vitro biocompatibility study will be conducted to validate the biological response.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Davis, R. et al. A comprehensive review on metallic implant biomaterials and their subtractive manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. (Springer Lond. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-022-08770-8 (2022).

Uddin, M. S. et al. Surface treatments for controlling corrosion rate of biodegradable Mg and Mg-based alloy implants surface treatments for controlling corrosion rate of biodegradable Mg and Mg-based alloy implants. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 16, 53501 (2015).

Shayesteh, N. et al. Metals for bone implants: safety, design, and efficacy. Biomanufacturing Rev. 1, 1–16 (2016).

Marin, E. & Lanzutti, A. Biomedical applications of titanium alloys. Compr. Rev. Mater. 17, 1–42 (2024).

Phasani, M., Abe, J., Popoola, P., Aramide, O. & Dada, M. Synthesis and characterization of Cobalt-chromium based alloys via spark plasma sintering for biomedical applications. Mater 6, 100291 (2025).

Tsakiris, V., Tardei, C. & Clicinschi, F. M. Biodegradable Mg alloys for orthopedic implants – A review. J. Magnes Alloys. 9, 1884–1905 (2021).

Bairagi, D. & Mandal, S. A comprehensive review on biocompatible Mg-based alloys as temporary orthopaedic implants: current status, challenges, and future prospects. J. Magnes Alloys. 10, 627–669 (2022).

Amukarimi, S. Biodegradable magnesium-based biomaterials: an overview of challenges and opportunities. MedComm-Open Access. 123–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/mco2.59 (2021).

Hadisadegh, S. N., Ghanbarikondori, P., Sedighi, A., Ayouni, I. & Javadpour, N. Mproving Cancer therapy: design, synthesis, and evaluation of Carboplatin-Based nanoliposomes against breast Cancer cell lines. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Biol. 9, 1–30 (2024).

Ali, A., Madan, M. & Rayguru Payman SharafianArdakani; Irina Kondaurova; Dan O. Popa. Multi-Joint Adaptive Motion Imitation in Robot-Assisted Physiotherapy with Dynamic Time Warping and Recurrent Neural Networks. in IEEE Xplore SouthEastconAtlanata, GA, USA, (2024).

Yari, A., Fasih, P., Hooshiar, M. H. & Goodarzi, A. Detection and classification of mandibular fractures in panoramic radiography using artificial intelligence. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 53, 363–371 (2024).

Hosseini, M. M. et al. Intra-Examiner reliability and validity of sagittal cervical spine mensuration methods using deep convolutional neural networks. J. Clin. Med. 13, 1–18 (2024).

Fatemeh Eskandari, M., Aali, S. N. & Hadisadegh M. Advances in breast cancer research using CRISPR/Cas9 system. Nan0 Sel. 5, 1–10 (2024).

Majdi, A. et al. Bio-ceramic coatings adhesion and roughness of biomaterials through PM-EDM: a comprehensive review. Mater. Manuf. Process. 35, 1157–1180 (2020).

Klocke, F., Schwade, M., Klink, A. & Kopp, A. EDM machining capabilities of magnesium (Mg) alloy WE43 for medical applications. Procedia Eng. 19, 190–195 (2011).

Azeez, A. et al. A Review of Additive Mixed-Electric Discharge Machining: Current Status and Future Perspectives for Surface Modification of Biomedical Implants. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1–23 (2017). (2017).

Rehan, M., Ali, S., Rakhshanda, K., Muhammad, N. & Saqib, U. Experimental investigation of the influence of wire offset and composition on complex profile WEDM of Ti6Al4V using trim – pass strategy. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 127, 1209–1224 (2023).

Kumar, S., Varol, T., Canakci, A., Kumaran, T. & Uthayakumar, M. A review on the performance of the materials by surface modi Fi cation through EDM. Int. J. Lightweight Mater. Manuf. 4, 127–144 (2021).

Davis, R. et al. Surface modification of biodegradable Mg alloy by adapting µ EDM capabilities with cryogenically – treated tool electrodes. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 4617–4636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-023-11395-0 (2023).

Majdi, A. et al. Powder mixed-EDM for potential biomedical applications: A critical review ABSTRACT. Mater. Manuf. Process. 00, 1–23 (2020).

Kumar, A. & Singh, A. Surface modification of magnesium alloy AZ91D using nanopowder mixed electrical discharge machining for biodegradable implant. J. Long. Term Eff. Med. Implants. 34, 83–94 (2024).

Davis, R. et al. Effect of powder particle concentration and tool electrode material amid zinc powder-Mixed l EDM of biocompatible Mg alloy AZ91D. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 30, 5704–5718 (2021).

Klocke, F., Schwade, M., Klink, A., Veselovac, D. & Kopp, A. Influence of electro discharge machining of biodegradable magnesium on the biocompatibility. Procedia CIRP. 5, 88–93 (2013).

Byun, S., Lim, H., Lee, H. K. J. & Lee, S. Biodegradable magnesium alloy (WE43) in bone-fixation plate and screw. Orignal Res. Rep. Soc. Biomaterials Wiley. 2505–2512. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.b.34582 (2020).

Jin, W. et al. Hafnium-implanted WE43 magnesium alloy for enhanced corrosion protection and biocompatibility. Surf. Coat. Technol. 306, 11–15 (2016).

Id, E. G., Jaiswal, S. & Duffy, B. In vitro corrosion and biological assessment of bioabsorbable WE43 Mg alloy specimens. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 1, 1–9 (2017).

Witte, F., Kaese, V., Haferkamp, H. & Switzer, E. & Meyer-lindenberg, A. In vivo corrosion of four magnesium alloys and the associated bone response. Biomaterials. 26, 3557–3563 (2005).

Sugunakar, A., Kumar, A. & Markandeya, R. Effect of powder mixed dielectric fluid on surface integrity by electrical discharge machining of RENE 80. IOSR J. Mech. Civ. Eng. IOSR-JMCE. 14, 43–50 (2017).

Cuong, N. M., Tung, L. A., Do, V. T. & Thu, Q. Le. Electrical Discharge Machining with SiC Powder-Mixed Dielectric: An Efective Application in the Machining Process of Hardened 90CrSi Steel. machines 36, 1–12 (2020).

Ahmed, Y. & Rehman, M. A. U. Improvement in the surface properties of stainless steel via zein/hydroxyapatite composite coatings for biomedical applications. Surf. Interfaces. 20, 100589 (2020).

Sun, K. et al. Bioactive materials osteogenesis and angiogenesis of a bulk metallic glass for biomedical implants. Bioact Mater. 8, 253–266 (2022).

Singh, G. et al. On surface modification of Ti alloy by electro discharge coating using hydroxyapatite powder mixed dielectric with graphite tool. J. Bio- Tribo-Corros. 6, 1–11 (2020).

Prakash, C., Kansal, H. K., Pabla, B. S. & Puri, S. Processing and characterization of novel biomimetic nanoporous bioceramic surface on b -Ti implant by powder mixed electric discharge machining. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 24, 3622–3633 (2015).

Farooq, M., Umar, Mughal, M., Pervez, Ahmed, Naveed, Mufti, N. A., Al-ahmari, A. M. & He, Y. On the Investigation of Surface Integrity of Ti6Al4V ELI Using Si-Mixed Electric Discharge Machining. materials 13, 1–18 (2020).

Pervez, M. et al. Surface modification for osseointegration of Ti6Al4V ELI using powder mixed sinking EDM. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 113, 104145 (2021).

Ou, S. & Wang, C. Effects of bioceramic particles in dielectric of powder-mixed electrical discharge machining on machining and surface characteristics of titanium alloys. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 245, 70–79 (2017).

Banh, T. L., Nguyen, H. P. & Ngo, C. D.-T. N. Characteristics optimization of powder mixed electric discharge machining using titanium powder for die steel materials. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 232, 281–298 (2018).

Umar, M. et al. Surface generation on titanium alloy through powder – mixed electric discharge machining with the focus on bioimplant applications. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 1395–1411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-022-09927-1 (2022).

Kolli, M. & Kumar, A. Effect of dielectric Fluid with surfactant and graphite powder on electrical discharge machining of titanium alloy using Taguchi method engineering science and technology, an international journal effect of dielectric Fl Uid with surfactant and graphite powder on electrical discharge machining of titanium alloy using Taguchi method. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jestch.2015.03.009

Ehsan, S. et al. Machinability investigations through novel controlled Flushing characteristics in wire electric discharge machining of M42 high – speed steel. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 4717–4719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-023-12294-0 (2023).

Farooq, M. & Umar, Anwar, S. Investigations on the surface integrity of Ti6Al4V under modified dielectric (s) -Based electric discharge machining using cryogenically treated electrodes. Processes 877, 1–25 (2023).

Rehman, A. et al. Analysis of particle size and concentration in die sinking electric discharge machining Ata. Materials 4932, 1–26 (2022).

Thanigaivel, S. et al. Insight on recent development in metallic biomaterials: strategies involving synthesis, types and surface modification for advanced therapeutic and biomedical applications. Biochem. Eng. J. 187, 108522 (2022).

Sana, M., Asad, M., Umar, M., Saqib, F. & Muhammad, A. Machine learning for multi – dimensional performance optimization and predictive modelling of nanopowder – mixed electric discharge machining (EDM). Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 130, 5641–5664 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful for the support from Ongoing Research Funding Program, (ORF-2025-702), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sarmad Ali Khan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing, Reviewing and Editing, Muhammad Omer: Data curation, Methodology, Investigation and Writing the original draft, Muhammad Umar Farooq: Software, Formal analysis, Writing, Reviewing and Editing, Saqib Anwar: Validation, Funding acquisition, Writing Reviewing and Editing Adeolu A. Adediran: Analysis, Writing Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors agreed upon the current version of the submission for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, S.A., Omer, M., Farooq, M.U. et al. Effect of powder particle concentration, pulse duration, and pulse current on machined surface characterization produced via EDM of biocompatible WE-43Mg alloy. Sci Rep 15, 33927 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10123-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10123-w