Abstract

The diarylmethane backbone is a base of molecules relevant for various industrial and especially pharmaceutical applications where they serve as a platform for the discovery of new drugs. One of the most versatile methods of their synthesis are cross-coupling reactions that have served synthetic chemistry for nearly five decades and offer diverse opportunities for the synthesis of complex organic compounds. Although palladium catalysts have traditionally dominated this field, the emergence of first-row transition-metal (pre)catalysts presents promising alternatives because of their cost-effectiveness and the possibility of new reactivities. In this context, Negishi cross-coupling of benzylzinc bromide and its congeners with aryl, alkyl, alkenyl, alkynyl iodides and bromides, facilitated by simple cobalt halides without the addition of an auxiliary ligand, is presented. The optimisation of reaction conditions, including solvent selection, is discussed alongside the mechanistic insights gained through computational studies. A variety of diarylmethanes were synthesised under mild conditions, with yields comparable to those obtained with Pd catalysts, with excellent selectivity (> 99%) provided by commercially available anhydrous CoBr2 / DMAc catalytic system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

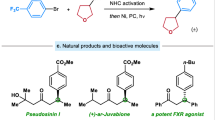

Diarylmethanes are useful platforms that can be easily modified by benzylic C-H functionalisation to give a variety of molecules of unique importance in pharmaceutical, agrochemical, and material sciences1. Their synthesis is a key step in the synthesis of various drugs, including antihistamines such as benadryl2, anticancer agents such as piritrexim3, vasodilators such as segontin4, and antidiabetics such as dapagliflozin, a sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor5. Due to this breadth of application, various methods of constructing diarylmethane backbone have been devised. The most handbook ones are different variations on Friedel-Crafts alkylation or Friedel-Crafts acylation / reduction protocols6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Methods aimed at diarylmethanes also cover classical Pd-catalysed Suzuki-Miyaura and related cross-couplings13,14,15,16, organocatalysed7 and radical reactions17,18,19,20,21, as well as iron-catalysed Kumada cross-coupling22 and cobalt-catalysed reductive coupling23,24. The report on the last of these describes also conditions for Negishi cross-coupling, although it was not the goal of that research.

Cross-coupling reactions with organometallic reagents have been established as synthetic tools for nearly 50 years25,26,27. Wide scope of reagents and great number of reaction conditions to choose from made these processes successful despite the frequent need for expensive palladium catalysts. Negishi reaction is one such example which uses organozinc reagents whose great advantage is the relative stability and low nucleophilicity compared to organolithium and organomagnesium reagents (used in Murahashi and Kumada reactions, respectively)28,29 while maintaining the ability for fast transmetallation, contrary to organoboron and organosilicon compounds (used in Suzuki-Miyaura and Hiyama reactions). Furthermore, organozinc reagents are considerably less toxic than equivalent organotin compounds still used in Stille cross-coupling30.

Even though the field of cross-couplings can be considered mature, it is still a realm of intense research, especially considering the trend to abandon using platinum-group-metal catalysts. Cobalt catalysis has emerged as a promising alternative, mainly due to its reactivity patterns, some of which are unique to this metal31,32,33. Although studied extensively, new base metal catalytic systems for cross-coupling reactions are still sought after, especially those that would combine mild reaction conditions with stability and simple structure of (pre)catalysts.

Figure 1 shows representative examples of such base-metal catalytic systems published over the past two decades. The first report on the cobalt-catalysed Negishi reaction dates back to 200934. Roy MacArthur et al. described Co(II) acetylacetonato derivative complexes capable of catalysing cross-coupling between (E)-1-iodo-1-octene and butylzinc iodide to form (E)‑5‑dodecene. In 2015, diarylzinc reagents were the subject of a report by Knochel et al., in which they described the CoCl2 / 2LiCl (20 mol%) + N,N,N’,N’‑tetramethylethanediamine (30 mol%) catalytic system whose use provided cross-coupling products with primary and secondary alkyl iodides36. By further development of their catalytic system, the Knochel group has made a significant contribution to advance Co-catalysed Negishi cross-couplings35,37,39. Further, Dorval et al. showed Negishi-type cross coupling of glutaramides with organozinc reagents enabled by 20 mol% of cobalt(II) bromide in 1,4-dioxane41. The authors observed that polar aprotic solvents were incompatible with their conditions. Recently, Cossy et al. have proposed and described a mechanism of cobalt-catalysed Negishi cross-coupling of arylzinc reagents with (hetero)aryl halides catalysed by CoCl2(bpy)2 system that fundamentally relied on Co(I) generation through solvent-dependent disproportionation of Co(II)40. The formation of highly active Co(I) species and their stabilization by acetonitrile have been verified based on X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy allied with DFT calculations. This CoCl2/bipyridine/acetonitrile system has been extended to the Negishi acylation and allylation. Most recently, Lu and colleagues performed an enantioselective transformation of α-bromoketones by using cobalt iodide (10 mol%) and chiral unsymmetrical N,N,N‑tridentate ligand42. Common to all the reports presented above is that the addition of auxiliary ligands or activation was required.

It appears that in the literature there is no example of effective synthesis of diarylmethanes using Negishi cross coupling in a catalytic system comprised of a cobalt(II) (pre)catalyst without additives. Here, we report Negishi cross-coupling of benzylzinc bromide and its congeners with organic iodides and bromides catalysed by CoBr2 / solvent system, which turned out to be useful method of the synthesis of diarylmethanes. DFT studies were undertaken to shed light on the workings of the process described.

Results and discussion

Experimental research

The research began with cross-coupling experiments between phenylzinc bromide and 4-iodotoluene in tetrahydrofuran (THF) catalysed by cobalt(II) complexes (see SI). These preliminary results indicated that, although possible, such a reaction was very nonselective, yielding the desired 4-methylbiphenyl in yields lower than 40% with other products resulting from homocoupling of the starting reactants. Curious as to whether the low selectivity is due to the influence of an aromatic Negishi reagent or whether it is an inherent property of the catalytic systems used, further experiments were conducted with benzylzinc bromide 1 as a coupling partner for 4-iodotoluene 2 (Fig. 2). Table 1 summarises the screening of various cobalt coordination complexes as potential (pre)catalysts of such Negishi cross-coupling.

All cobalt compounds presented above turned out to catalyse the Negishi cross-coupling of benzylzinc bromide with 4-iodotoluene. Unexpectedly, the highest conversion of 4-iodotoluene was delivered by the simple, commercially available anhydrous cobalt(II) bromide (79%, entry 6), followed by two unrelated complexes (entries 1 and 8, 70% and 69%, respectively). It should be noted that reactions with simple Co halides (entries 5–6) were visibly more selective than those catalysed by other Co species. Having chosen the precatalyst, the next logical step was to determine the influence of the solvent, especially as a means of potentially increasing the yield of 3. These experiments are summarised in Table 2.

As demonstrated by the results in the table, a variety of solvents, both very well known in the Negishi reaction and noncanonical ones, were reaction media appropriate for carrying out the model reaction. The least successful turned out to be eucalyptol (61%; entry3), an ether considered a green alternative to other ether solvents, such as tetrahydrofuran (THF) and 1,4-dioxane. The use of both of the latter led to conversions of 90% and 86% (entries 1 and 2, respectively), but the highest yield of 3a with excellent selectivity (> 99%) was provided by N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAc, entry 4) and it was the solvent of choice for the last step of optimisation of reaction conditions, i.e., screening of catalyst loading, whose results are presented in Fig. 3 and the inset table. The collected data suggested that for future complete conversion of more demanding aryl iodides, 5 mol% of CoBr2 and a reaction time longer than 8 h should be applied.

Concluding, the screening has shown that 5 mol% of CoBr2 without an additive is enough to achieve full conversion of 4-iodotoluene over about 6 h at 80 ºC.

During considerations regarding the role of solvent in this transformation, the evaporation of THF from the solution of benzylzinc bromide prior to the addition of DMAc was tried. Decreasing the amount of THF allowed for a higher conversion of 2 (see SI), and this information together with the data from Tables 1 and 2 led us to the conclusion that only a small amount of solvent (N,N-dimethylacetamide) is required. In fact, it was possible to perform a reaction of 1 mmol of 2 in only 0.2 ml of DMAc without THF which enabled full conversion of aryl iodides at the room temperature with the same selectivity.

Having optimised the reaction conditions, we proceeded to examine the substrate scope of the proposed catalytic system (Fig. 4). Aryl iodides with groups such as methyl, methoxy, acyl, trifluoromethyl, nitrile, nitro, and amine were examined. Surprisingly, in reactions with alkyl iodides such as 1-iodohexane (3o), 2-iodopropane (3p), complete conversion of substrates was obtained as well as it was in the reaction of (E)‑β‑iodostyrene (3x) We observed that, most probably due to coordination properties, nitro and especially the amino groups were not suitable reagents for cross-coupling in this particular reaction system. A low conversion of these iodobenzene derivatives was recorded, but also many unidentified byproducts were observed. However, it is worth noting that a gramme-scale Negishi reaction between benzylzinc bromide and 4-iodoanisole resulted in isolating product 3e with a 98% yield. It is also significant that the reaction with p-bromoiodobenzene at room temperature led to the sole substitution of the iodine atom, leaving the bromine unreacted (3q), which opens the possibility for further functionalisation.

Knowing the importance and greater accessibility of aryl bromides, we attempted to modify the reaction conditions to include this class of reagents. It turned out that a modification of the conditions by increasing the temperature and CoBr2 loading allowed us to carry out cross-coupling of these as far unreactive reagents.

The results of the Negishi benzylation of selected aryl bromides are presented in Fig. 5. The cross-coupling reaction carried out at a higher temperature was accompanied by the formation of slightly higher amounts of 1,2-diphenylethane compared to the reactions with aryl iodides.

Regarding the variability of the organozinc coupling partner, 2-naphthylmethylzinc bromide was also successfully transformed, as well as 3,5-difluorobenzylzinc bromide and 4-cyanobenzylzinc bromide. A couple of common products show a comparison in the reactivity of organic bromides and iodides, where the latter turned out to be significantly easier to convert.

Distinct conditions required to carry out reactions with aryl iodides vs. aryl bromides were a premise that a sequential chemoselective cross-coupling of these moieties might be possible, which was demonstrated using 1‑bromo‑4‑iodobenzene (Fig. 6).

Furthermore, to ensure that our system was homogeneous, we decided to use scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to analyse the sample of solid residue separated from the reaction mixture. Energy-dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) showed no presence of cobalt, which allowed us to conclude about the absence of catalytic metal nanoparticles.

Theoretical modelling

To gain insight into the mechanistic details, the reaction was investigated computationally (Fig. 7). Reaction paths in both singlet and triplet states were considered. Generally, the triplet pathway (black and grey) is strongly preferred over the singlet pathway (blue), which is consistent with the reported models for cross-couplings catalysed by Co complexes (typically with N-ligands)40. Furthermore, complexes with a variety of coordinated solvent molecules were investigated.

The initial generation of Co(I) species has already been extensively described40. Triplet Co(I) complexes prefer flat trigonal over tetrahedral geometries (cf. I with II and IV with VI), also contrasting with singlet square planar arrangements (III and V). In contrast, Co(III) intermediates adopt only slightly distorted tetrahedral geometries favoured over trigonal bipyramidal and octahedral complexes bearing more solvent molecules (cf. IX with VII and XI and XII with XV).Therefore, the most probable pathway (black) involves facile oxidative addition (TS1) followed by rate-limiting transmetalation (TS 4) and reductive elimination (TS8). Transmetalation occurs through a four-membered transition state involving bridging of the Co and Zn centres by bromide and benzyl ligands. The most favourable pathway for this step involves initial substitution of a solvent molecule in BnZnBr(DMAc)2 with bromide coordinated to Co centre of IX leading to µ2 bromide bridging Zn and Co centres, (not depicted in Fig. 7) followed by transfer of benzyl via TS4 (ΔG‡= 76.9 kJ/mol). The alternative manifolds involving pentavalent Zn-centre (TS5) or hexavalent Co-centre (TS7) are considerably higher in energy. Finally, intermediate XII undergoes relatively easy reductive elimination through TS8 (ΔG‡= 54.9 kJ/mol). The resulting catalytic cycle is presented in Fig. 8.

Conclusions

In conclusion, a straightforward method for performing the Negishi cross-coupling benzylation of aryl halides using the simplest cobalt precatalyst, cobalt bromide, in N,N-dimethylacetamide without addition of auxiliary ligands has been devised. With the use of the mild conditions described in the article, 26 products, including a variety of diarylmethanes, were synthesised, which was accomplished with yields comparable to those obtained with Pd catalysts. Additionally, the method has the potential to be extended to include alkyl alkenyl, and alkynyl iodides and bromides as coupling partners for arylmethylzinc bromides. At room temperature, the reaction is chemoselective toward aryl iodides, whereas carrying it out at elevated temperature allows for the transformation of aryl bromides, thus unlocking the possibility of sequential functionalisation. The role of solvent coordination in this transformation seems crucial and has been explained on the basis of DFT calculations.

Methods

General remarks

All reactions were carried out under argon atmosphere using standard Schlenk techniques and thoroughly dried glassware. Liquids were transferred using disposable syringes. N,N-dimethylacetamide (Merck/Sigma-Aldrich) was transferred to a Schlenk flask and degassed prior to use. Negishi reagents were prepared from the respective arylmethyl bromides in a direct reaction with zinc and their concentrations were determined by titration against iodine. Anhydrous cobalt(II) bromide and other reagents were purchased from Merck/Sigma-Aldrich and used as received.

General procedure of Negishi cross coupling

A calculated volume of solution of arylmethylzinc bromide in THF containing 4 mmol (2 eq. respectively to aryl halide) of this reagent was placed in a carefully dried Schlenk bomb flask with a PTFE valve plug. The introduced THF was evaporated in vacuo through the Schlenk line. Then, dimethylacetamide (0.4 ml), the corresponding organic halide (1 eq., 2 mmol) and cobalt bromide (21.8 mg, 5 mol%, 0.1 mmol) were added. After closing, the reaction mixture was stirred for 20 h at room temperature (for ArI), or at 80 °C (for ArBr). The mixture was quenched with concentrated aqueous NH4Cl solution (10 ml) and ethyl acetate (10 ml) was added. The mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 10 ml). The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. Trace amounts of DMAc were removed by prolonged evacuation on the Schlenk line.

Theoretical modelling

Calculations were conducted with Gaussian 16 package43. Structures of minima and transition states were optimized employing BP86 functional, def2-SVP basis set44 Frequency analysis was performed at the same level of theory to provide correction to thermodynamic functions and confirm the nature of optimized structures (minima and transition states featured zero and one imaginary frequency, respectively). Single point energies were calculated with BP86 functional employing def2-TZVPP44 basis set and solvation (N,N-dimethylacetamide) with the SMD model45. Molecular structures were visualized in CYLview46.

Data availability

All underlying data is available in the article itself and the accompanying Supplementary Material.

References

Gulati, U., Gandhi, R. & Laha, J. K. Benzylic methylene functionalizations of diarylmethanes. Chem. – Asian J. 15, 3135–3161 (2020).

MacQuiddy, E. L., Holyoke, E. A. & ALLERGY Summaries of the bibliographic material available in the field of otolaryngology for 1949. Arch. Otolaryngol. - Head Neck Surg. 53, 560–595 (1951).

Zink, M., Lanig, H. & Troschütz, R. Structural variations of piritrexim, a lipophilic inhibitor of human dihydrofolate reductase: Synthesis, antitumor activity and molecular modeling investigations. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 39, 1079–1088 (2004).

Lamers, J. M. J., Cysouw, K. J. & Verdouw, P. D. Slow calcium channel blockers and calmodulin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 34, 3837–3843 (1985).

Washburn, W. N. Chapter Twenty-Three - Case History: ForxigaTM (Dapagliflozin), a Potent Selective SGLT2 Inhibitor for Treatment of Diabetes. in Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry (ed. Desai, M. C.) vol. 49 363–382Academic Press, (2014).

Kobayashi, T. & Rahman, S. M. A simple Preparation of diarylmethanes by oxidative Friedel-Crafts reaction of Methyl-Substituted benzenes with o-Chloranil. Synth. Commun. 33, 3997–4003 (2003).

Kumar, A., Kumar, M. & Gupta, M. K. An efficient organocatalyzed multicomponent synthesis of diarylmethanes via Mannich type Friedel–Crafts reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 50, 7024–7027 (2009).

Tang, R. J., Milcent, T. & Crousse, B. Bisulfate Salt-Catalyzed Friedel–Crafts benzylation of Arenes with benzylic alcohols. J. Org. Chem. 83, 14001–14009 (2018).

Mo, X., Yakiwchuk, J., Dansereau, J., McCubbin, J. A. & Hall, D. G. Unsymmetrical diarylmethanes by ferroceniumboronic acid catalyzed direct Friedel–Crafts reactions with deactivated benzylic alcohols: enhanced reactivity due to Ion-Pairing effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 9694–9703 (2015).

Forster, F., Metsänen, T. T., Irran, E., Hrobárik, P. & Oestreich, M. Cooperative Al–H bond activation in DIBAL-H: Catalytic generation of an Alumenium-Ion-Like Lewis acid for hydrodefluorinative Friedel–Crafts alkylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 16334–16342 (2017).

Mendoza, O., Rossey, G. & Ghosez, L. Brönsted acid-catalyzed synthesis of diarylmethanes under non-genotoxic conditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 52, 2235–2239 (2011).

Seki, M., Tapkir, S. R., Nadiveedhi, M. R., Mulani, S. K. & Mashima, K. New synthesis of diarylmethanes, key Building blocks for SGLT2 inhibitors. ACS Omega. 8, 17288–17295 (2023).

Kuriyama, M., Shinozawa, M., Hamaguchi, N., Matsuo, S. & Onomura, O. Palladium-Catalyzed synthesis of Heterocycle-Containing diarylmethanes through Suzuki–Miyaura Cross-Coupling. J. Org. Chem. 79, 5921–5928 (2014).

Zhang, P. et al. Synthesis of diarylmethanes through Palladium-Catalyzed coupling of benzylic phosphates with arylsilanes. Synlett 25, 2928–2932 (2014).

Chen, M. T., Wang, W. R. & Li, Y. J. N-heterocyclic carbene–palladium complexes for Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reaction with benzyl chloride and aromatic boronic acid leading to diarylmethanes. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 33, e4912 (2019).

Endo, K., Ishioka, T., Ohkubo, T. & Shibata, T. One-Pot synthesis of symmetrical and unsymmetrical diarylmethanes via diborylmethane. J. Org. Chem. 77, 7223–7231 (2012).

Dhanwant, K., Bhedi, D., Bhanuchandra, M. & Thirumoorthi, R. Situ generated 1-Naphthylmethyl radicals from Bis(1-Naphthylmethyl)tin dichlorides: utilization for C – C, C – N, and C – O Bond-Forming reactions. Asian J. Org. Chem. 14, e202400593 (2025).

Crowley, I. I. I. A Fenton approach to aromatic radical cations and diarylmethane synthesis. J. Org. Chem. 88, 15060–15066 (2023).

Zhou, S. L., Guo, L. N. & Duan, X. H. Copper-Catalyzed regioselective Cross-Dehydrogenative coupling of coumarins with benzylic Csp3–H bonds. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 8094–8100 (2014).

Wan, M., Lou, H. & Liu, L. C1-Benzyl and benzoyl isoquinoline synthesis through direct oxidative cross-dehydrogenative coupling with Methyl Arenes. Chem. Commun. 51, 13953–13956 (2015).

Vasilopoulos, A., Zultanski, S. L. & Stahl, S. S. Feedstocks to pharmacophores: Cu-Catalyzed oxidative arylation of inexpensive alkylarenes enabling direct access to diarylalkanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 7705–7708 (2017).

Ma, X., Wang, H., Liu, Y., Zhao, X. & Zhang, J. Mixed alkyl/aryl diphos ligands for Iron-Catalyzed negishi and Kumada cross coupling towards the synthesis of diarylmethane. ChemCatChem 13, 5134–5140 (2021).

Amatore, M. & Gosmini, C. Synthesis of functionalised diarylmethanes via a cobalt-catalysed cross-coupling of Arylzinc species with benzyl chlorides. Chem. Commun. 5019–5021 (2008).

Reddy, B. R. P., Chowdhury, S., Auffrant, A. & Gosmini, C. Cobalt-Catalyzed formation of functionalized diarylmethanes from benzylmesylates and Aryl halides. Adv. Synth. Catal. 360, 3026–3029 (2018).

Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions and More. Vol. 3. vol. 3 (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, (2014).

Pérez Sestelo, J. & Sarandeses, L. A. Advances in Cross-Coupling reactions. Molecules 25, 4500 (2020).

Ruiz-Castillo, P. & Buchwald, S. L. Applications of Palladium-Catalyzed C–N Cross-Coupling reactions. Chem. Rev. 116, 12564–12649 (2016).

Negishi, E., King, A. O. & Okukado, N. Selective carbon-carbon bond formation via transition metal catalysis. 3. A highly selective synthesis of unsymmetrical biaryls and diarylmethanes by the nickel- or palladium-catalyzed reaction of Aryl- and benzylzinc derivatives with Aryl halides. J. Org. Chem. 42, 1821–1823 (1977).

Farhang, M., Akbarzadeh, A. R., Rabbani, M. & Ghadiri, A. M. A retrospective-prospective review of Suzuki–Miyaura reaction: from cross-coupling reaction to pharmaceutical industry applications. Polyhedron 227, 116124 (2022).

Kimbrough, R. D. Toxicity and health effects of selected Organotin compounds: a review. Environ. Health Perspect. 14, 51–56 (1976).

Schiltz, P., Gao, M. & Gosmini, C. Cobalt-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling reactions. in Base-Metal Catalysis 2 vol. 3 (Georg Thieme Verlag KG, Stuttgart, (2023).

Cobalt Catalysis in Organic Synthesis: Methods and Reactions. (Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, Weinheim, (2020).

Non-Noble Metal Catalysis: Molecular Approaches and Reactions. (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany, (2019).

Struzinski, T. H., Gohren, V., Roy MacArthur, A. H. & L. R. & Modified cobalt(II) acetylacetonate complexes as catalysts for Negishi-type coupling reactions: influence of ligand electronic properties on catalyst activity. Transit. Met. Chem. 34, 637–640 (2009).

Palao, E. et al. Formation of quaternary carbons through cobalt-catalyzed C(sp 3)–C(sp 3) Negishi cross-coupling. Chem. Commun. 56, 8210–8213 (2020).

Hammann, J. M., Haas, D. & Knochel, P. Cobalt-Catalyzed negishi Cross‐Coupling reactions of (Hetero)Arylzinc reagents with primary and secondary alkyl bromides and Iodides. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 4478–4481 (2015).

Haas, D., Hammann, J. M., Lutter, F. H. & Knochel, P. Mild Cobalt-Catalyzed negishi Cross‐Couplings of (Hetero)arylzinc reagents with (Hetero)aryl halides. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 3809–3812 (2016).

Benischke, A. D., Knoll, I., Rérat, A., Gosmini, C. & Knochel, P. A practical cobalt-catalyzed cross-coupling of benzylic zinc reagents with Aryl and heteroaryl bromides or chlorides. Chem. Commun. 52, 3171–3174 (2016).

Lutter, F. H., Grokenberger, L., Benz, M. & Knochel, P. Cobalt-Catalyzed Csp 3 –Csp 3 Cross-Coupling of functionalized alkylzinc reagents with alkyl Iodides. Org. Lett. 22, 3028–3032 (2020).

Luo, X. et al. Valve turning towards on-cycle in cobalt-catalyzed Negishi-type cross-coupling. Nat. Commun. 14, 4638 (2023).

Dorval, C. et al. Cobalt Bromide-Catalyzed Negishi-Type Cross-Coupling of amides. Org. Lett. 24, 2778–2782 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Cobalt-Catalyzed enantioconvergent negishi Cross-Coupling of α-Bromoketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 24958–24964 (2023).

Gaussian 16, Revision, C. et al. J. W. R. L. Mar-tin, K. Morokuma, O. Farkas, J. B. Foresman, and D. J. Fox, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, (2019).

Weigend, F. & Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split Valence, triple zeta Valence and quadruple zeta Valence quality for H to rn: design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 7, 3297–3305 (2005).

Marenich, A. V., Cramer, C. J. & Truhlar, D. G. Universal solvation model based on solute Electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B. 113, 6378–6396 (2009).

CYLview20 & Legault, C. Y. Université De Sherbrooke, (2020). http://www.cylview.org).

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to Professor Bronisław Marciniak on the occasion of his 75th birthday. The authors would like to thank Jakub Zembrzuski (AMU Faculty of Chemistry) for his input at the early conception of this research.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the National Science Centre, Poland (NCN), grant UMO-2019/35/B/ST4/00329 (P.P.). Calculations have been carried out using resources provided by Wroclaw Centre for Networking and Supercomputing, grant 518 (W.C.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript. J.R.: investigation, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing; W.C.: investigation, writing – original draft, writing – review &editing; P.P.: conceptualisation, funding acquisition, supervision, writing – review & editing; M.Z.: conceptualisation, investigation, validation, project administration, supervision, writing – original draft, writing – review &editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Robaszkiewicz, J., Chaładaj, W., Pawluć, P. et al. Synthesis of diarylmethanes by means of Negishi cross-coupling enabled by cobalt-solvent coordination. Sci Rep 15, 26809 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10180-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10180-1