Abstract

A new regional navigation satellite system that uses the L6 band to provide Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT) services is being developed in Korea. However, in addition to the Radio Navigation Satellite Service (RNSS), the L6 band is shared with other services, leading to potential interference between services. Therefore, it is essential to analyze how interference signals in this band impact RNSS receivers. In this study, we investigated the radio frequency environment of the L6 band and experimentally analyzed the effects of interference signals on RNSS receiver performance. The results demonstrate that interference signals in the L6 band can significantly degrade the RNSS signal quality, adversely affecting both signal stability and positioning accuracy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Position, Navigation, and Timing (PNT) information provided by the Radio Navigation Satellite Service (RNSS) is crucial for a wide range of applications across various fields. Consequently, many spacefaring nations have prioritized the operation, modernization, and enhancement of Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSSs). In line with this global trend, Korea plans to establish a new regional navigation satellite system by 2035 to deliver accurate PNT services for Korea and its surrounding regions1.

These systems operate within the frequency bands allocated by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) for the RNSS or Radio Determination Satellite Service (RDSS)2. According to the ITU Radio Regulations, RNSS operations are permitted in the L- (1,164–1,300 and 1,559–1,610 MHz), S- (2,483.5–2,500 MHz), and C-bands (5,010–5,030 MHz). Korea plans to provide services using the L- and S-bands3. Among them, the L6 band (1,260–1,300 MHz) is particularly noteworthy, as it is shared not only with the RNSS but also with other services, including the Earth Exploration Satellite Service (EESS), Radiolocation Service (RLS), Space Research Service (SRS), and Amateur Service (AS)2. The coexistence of multiple services within the same band significantly increases the probability of radio frequency interference (RFI) affecting RNSS receivers in the L6 band.

For example, the synthetic aperture radar (SAR), an active sensor used in EESS, generates pulse signals that can intermittently interfere with RNSS receivers, depending on the radar system’s characteristics4,5. Additionally, the RLS employs numerous radar systems globally for surveillance purposes that transmit extremely high-power pulse signals with durations ranging from a few microseconds to several milliseconds4. These high-power signals can severely affect RNSS receivers operating in the same frequency band. Furthermore, under ITU Radio Regulation No. 5.329, the RLS has a higher priority than the RNSS. Consequently, even if RLS signals cause harmful interference to the RNSS, the coordination between the two systems may prove challenging.

By contrast, the AS is the only secondary service within the band and is permitted to operate under ITU Radio Regulation No. 5.282 on the condition that it does not interfere with the primary service, i.e., the RNSS. This indicates that the interference from the AS can be managed easily through mutual coordination. However, the active use of the AS in the L6 band with various signal types still makes it a potential source of interference for RNSS receivers6,7,8.

Given these complexities, the operation of RNSS receivers in the L6 band is highly challenging. Therefore, it is essential to evaluate the potential interference impacts prior to completing the design of Korea’s new regional navigation satellite system. However, analyzing the interference from RLS systems is particularly challenging because of the lack of publicly available information regarding their characteristics, and research in this area remains limited.

Meanwhile, some studies have examined the effects of AS interference on Galileo E6 signals. For instance7, reported that Amateur TV signals transmitted in Europe reduced the carrier-to-noise density ratio (C/N0) of Galileo E6 RNSS receivers by approximately 10 dB, significantly degrading signal reception. Another study8, evaluated the impact of the AS on Galileo E6 signals in a highway-driving environment in Germany by assessing the coexistence potential of the two services. The findings suggest that while the AS affects RNSS receivers, coexistence could be feasible with appropriate measures such as power restrictions on AS signals and improved RNSS receiver robustness. These previous studies highlight the fact that RNSS receivers in the L6 band are likely to be affected by various interference sources.

Previous studies have indicated that most interference sources affecting RNSS receivers are ground-based. These services are geographically constrained, limited by the range of specific base stations or transmitters, and influenced by the terrain, resulting in relatively narrow service areas. Consequently, the interference effects on RNSS receivers are highly dependent on the characteristics of nearby RLS or AS systems. This variability makes it difficult to directly apply the findings of European studies to Korea. Furthermore, because the RLS is expected to have a greater impact on interference than the AS, additional analysis is necessary to better understand and address these challenges.

This study aimed to adapt prior research to the regional characteristics of Korea and evaluate the potential RFI impacts in the L6 band. Actual signal data were collected to analyze the L6 band environment in Korea, and the C/N0 degradation experienced by RNSS receivers in this environment was quantitatively assessed.

L6 band envrionment

The ITU defines the frequency bands available for each service according to region to ensure the efficient allocation of frequency resources. Table 1 summarizes the service allocation statuses of the L6 band. The EESS, RLS, SRS, AS, and RNSS are allocated to all regions. This implies a high probability that all services in Table 1 are also provided in Korea. The coexistence of multiple services within the same frequency band significantly increases the likelihood of interservice interference. To mitigate this, the ITU provides radio regulations for the L6 band to ensure the stable operation of each service listed in Table 1 and minimize potential interference.

Table 2 presents the key radio regulations related to the compatibility between the services listed in Table 1. These regulations clarify the status of services assigned to the band. According to the regulations, the RLS holds the highest priority within the band, and the ITU enforces restrictive regulations to protect services with higher priority allocations.

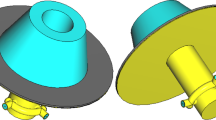

The RLS uses radio waves for object location detection and frequently transmits extremely high-power pulse signals, which can significantly degrade RNSS receiver performance. As the primary source of potential interference, the RLS operates as a ground-based system under national regulations. It is crucial to investigate the RLS network configuration and operational scenarios in Korea. Figure 1 illustrates the structure and operation of the RLS network in Korea. Similar to the RNSS, the RLS is assigned to multiple frequency bands, with each band serving a different purpose. The RLS operating in the L-band is predominantly used for surveillance radar applications11,12. Research indicates that Lockheed Martin’s long-range air search radar currently operates in Korea’s L6 band13. While additional radar systems are likely to operate, the limited availability of publicly disclosed information owing to system confidentiality makes it challenging to identify these systems. Therefore, it is essential to verify the activity of the identified interference sources within the L6 band. To achieve this, a spectrum analyzer (SA) was used to monitor the L6 band environment.

Network configuration and operational cases of the RLS6.

Figure 2 illustrates the experimental setup, in which signals captured by an antenna installed on the rooftop of the High-Tech Building at Inha University (Incheon, South Korea) were transmitted indoors for analysis using the SA. Figure 3 illustrates the observation results, showing the power spectral density (PSD) of signals in the L1 and L6 bands at a specific moment. In the L1 band, interference signals were nearly absent, resulting in a clean spectrum. This indicates that an interference-free environment is conducive to the smooth RNSS operation in the L1 band. By contrast, the L6 band exhibits high-power interference signals across multiple frequencies, predominantly in the form of pulsed signals. These results suggest the presence of significant interference sources such as RLS systems operating in the L6 band. Repeated observations at different locations confirmed that the narrowband interference signals shown in Fig. 3(b) are not isolated phenomena, but are consistently observed across various regions in Korea. These interference signals, with power levels reaching 40 dB above the noise floor, could substantially degrade the RNSS receiver performance.

Additional experiments were conducted to investigate the transmission directionality of the observed interference signals. Figure 4 illustrates the experimental setup, which closely resembles the original configuration but replacing a high-gain directional antenna for directionality analysis. Figure 5 shows the results of signals received from the east, west, south, and north directions at Inha University. These results indicate that interference signals were detected from all directions, with directional variations in the observed interference patterns. Instances of rapidly incoming broadband interference signals were also identified, suggesting the potential presence of sources such as the AS. Although no distinct frequency characteristics indicative of services other than RLS and AS were observed, the possibility of interference originating from other unidentified services cannot be ruled out.

The interference signals detected in the L6 band highlight concerns regarding their RNSS receiver performance degradation potential. To ensure the stable operation of Korea’s planned regional navigation satellite system, it is crucial to evaluate the extent of performance degradation that RNSS receivers may experience in such an environment.

Methodology

The simplest method for analyzing the degradation of the target signal quality caused by interference is to compare the C/N0 of the target signal under both interference-free and interference-present conditions. However, this straightforward approach is impractical in the L6 band, where interference signals are continuously observed. To overcome this limitation, a simulation-based experimental methodology was introduced in this study.

The fundamental concept of the proposed methodology is illustrated in Fig. 6 This approach quantitatively evaluates the impact of interference by combining the recorded interference signals with simulation-based navigation signals to generate two types of signal files: SF-RFI and SF-NoRFI. The results of processing these signal files were compared and analyzed.

The use of simulated signals in this methodology is justified for two primary reasons. First, it is challenging to directly predict the baseline signal quality required for quantitatively assessing the impact of interference on recorded navigation signals. Only the C/N0 values already influenced by RFI can be observed, making it difficult to estimate the unaffected C/N0. This limitation hinders the precise evaluation of interference effects on navigation signals. Second, the simulated signals enable experiments with various modulation waveforms, allowing the evaluation of the anti-jamming performance of the candidate waveforms in the intended frequency band before the RNSS is fully developed. However, because this study primarily focused on the impact of interference rather than waveform robustness, emphasis is placed on addressing the first reason.

The SF-RFI signal was constructed by combining the recorded L6 band signals with simulated navigation signals to assess the signal quality under interference conditions. By contrast, the SF-NoRFI signal was created by removing the interference components from the recorded signals, leaving only noise, and subsequently adding simulated signals. The SF-NoRFI signal establishes a baseline for the simulated signal quality, enabling the quantitative evaluation of the impact of interference on RNSS receivers.

Simulation setup

Figure 7 illustrates the experimental setup proposed in this study for interference impact evaluation, and Table 3 provides a summary of the signal recording environment and the characteristics of the generated simulated signals.

The experimental procedure involved the generation of two signal files, SF-RFI and SF-NoRFI, to assess the interference impact. To create these files, three signal components must first be prepared: the recorded signal, the reconstructed noise, and the simulation-based custom signal.

As shown in Fig. 7, the recorded signal is collected from the L6 band in an open-sky environment using an antenna installed on the rooftop of Inha University. The signals were transmitted indoors, where an amplifier compensated for the attenuation during transmission before being captured by the Universal Software Radio Peripheral (USRP). Detailed information on the recording environment is outlined in the “Recording” section of Table 3.

Figure 8 presents the frequency spectra of the recorded signals, revealing the interference from non-RNSS services within the band. Among the RNSS signals, the Galileo and QZSS high-accuracy service (HAS) signals were fully captured, whereas the Galileo E6 PRS and BDS signals were only partially recorded because of band limitations. Figure 9 illustrates the characteristics of the recorded L6 band signal during a 1s interval (0–1 s), highlighting the presence of various types of interference in the collected data.

The reconstructed noise was generated to match the noise level of the recorded signals. Figure 10 illustrates the characteristics of both the recorded signal and the reconstructed noise, confirming that the latter closely aligns with the noise level of the former. Although the reconstructed environment did not perfectly mirror the actual environment, it was assumed that the generated noise approximated an interference-free scenario in the L6 band.

A simulation-based custom signal was arbitrarily generated using a simulator, and its frequency spectrum is shown in Fig. 11. Because Korea’s regional navigation satellite service is still under development and the finalized parameters are yet to be disclosed, this study estimated and configured the signal characteristics and orbital parameters based on previous studies3,14,15,16. The key parameters used for signal generation are detailed in the “Simulation” section of Table 3.

As shown in Fig. 7, the custom signal generated by the simulator undergoes conditioning to ensure an appropriate signal quality. This process adjusts the C/N0 of the custom signal to fall within a range of 45–55 dB-Hz, depending on the satellite’s elevation angle, when combined with the reconstructed noise. Figure 12 illustrates the conditioning process. This process involves combining the custom signal with the reconstructed noise, processing the resulting signal, and fine-tuning the bit level of the custom signal until the desired C/N0 value is achieved for each satellite.

Once all three signal components are prepared, the SF-RFI and SF-NoRFI signal files are created and processed to complete the experiment. SF-RFI simulates an interference-affected environment, whereas SF-NoRFI represents an interference-free scenario. Both signals were processed using the AutoNav Software Defined Radio17.

Results

Figure 13 shows the C/N0 estimation results for SF-NoRFI. In an interference-free environment, the custom signal achieved a stable C/N0 of approximately 45–55 dB Hz, thereby confirming successful execution of the conditioning process. Additionally, seven of the eight satellites, excluding the one with the lowest elevation angle, were observed at a defined user location.

Figure 14 shows the C/N0 estimation results for SF-RFI along with those for the Galileo HAS signals included in the file. The presence of RFI caused a significant C/N0 reduction for both navigation signals. The two signals exhibit similar C/N0 estimation trends, suggesting that they are affected by the same interference source. Notably, both signals experienced sharp C/N0 drops at approximately 10 s intervals, strongly suggesting that the power level of the interference signals was elevated during those periods.

As SF-NoRFI establishes the baseline signal quality for the custom signal, the C/N0 degradation caused by interference can be quantitatively analyzed. Table 4 summarizes the signal processing results for the custom signal. Although the number of visible satellites remained unchanged regardless of interference, the C/N0 results exhibited substantial differences. During the simulation period, the custom signal experienced a maximum C/N0 degradation of approximately 18 dB and an average degradation of approximately 7 dB. These findings confirm that interference signals in the L6 band consistently and significantly affect the performance of RNSS receivers.

Figures 15 and 16 show the characteristics of the recorded signals during periods of minimal and significant C/N0 degradation, respectively. In Fig. 15, the time domain shows minimal fluctuations in the bit values, with weak peaks from the interference signals appearing in specific frequency ranges. Conversely, Fig. 16 reveals pronounced fluctuations in the bit values in the time domain and strong interference peaks distributed across the entire PSD. Notably, the high-power interference components were concentrated around 178.33 s, likely serving as the primary cause of signal quality degradation. These findings demonstrate that the power levels and characteristics of the interference signals directly influenced the C/N0 results.

An analysis of the interference signal types in the L6 band reveals that pulse-type signals have the most significant impact on RNSS receivers. This finding aligns with observations in the L5 band, where RNSS receivers are affected by pulse signals generated by equipment such as distance measuring equipment (DME) and tactical air navigation systems (TACAN)18. Extensive research has been conducted to mitigate pulse interference in the L5 band using pulse blanking (PB), which is widely recognized as an effective interference mitigation technique19,20. Building on this foundation, in this study, the PB technique was applied to RNSS signals in the L6 band and its effectiveness in terms of signal processing performance improvement was evaluated.

Figure 17 shows the results of applying the PB technique to SF-RFI. After applying the PB, both the E6 HAS and custom signals demonstrated stable C/N0 values, effectively resolving the significant C/N0 drops that occurred approximately every 10 s owing to interference.

Tables 5 and 6 summarize the mean and standard deviation of C/N0 for the E6 HAS and custom signals before and after applying the PB technique, respectively. Following the PB application, both signals exhibited an increase in the mean C/N0 and a decrease in its standard deviation, clearly illustrating the effectiveness of interference mitigation. Notably, the custom signal results closely matched those obtained in an interference-free environment. However, its standard deviation was slightly higher than that of SF-NoRFI. This can be attributed to the fact that the PB technique effectively mitigates interference while causing sample loss during the interference removal process, leading to a slight increase in signal variability.

The PB technique removes more samples when interference signals occur more frequently or persist for longer periods. Although this provides effective interference mitigation, it may also negatively impact the signal quality. Nevertheless, as shown in Fig. 17, the PB technique effectively mitigates interference in the L6 band. These findings suggest that PB must be considered an essential component in the design and implementation of RNSS receivers for the L6 band.

The signal quality can also be evaluated using metrics beyond C/N0. Figures 18, 19 and 20 show a detailed analysis of the custom signal processing results. For clarity, these figures focus on one inclined geosynchronous orbit satellite (PRN 4) among the seven visible satellites. The processing trends for the remaining six satellites are similar to those shown in Figs. 18, 19 and 20.

Figure 18 shows the estimation results for the code delay, Doppler frequency, and carrier phase of the custom signal, including the results for the entire simulation and a magnified view of the interference-intensive interval (178.3–178.35 s). The code delay results exhibit overall stability regardless of the presence of interference. However, in the magnified interval, a slight bias is observed in the code delay estimation for SF-RFI. After applying the PB technique to SF-RFI, this bias significantly decreased, producing results comparable to those obtained for SF-NoRFI. The Doppler frequency estimation results indicate that the estimation variance increases as the interference in the signal becomes more pronounced. The carrier-phase estimation results exhibit general stability, with only minor biases observed owing to interference, akin to the code delay behavior.

Figure 19 shows the discriminator output results. For SF-NoRFI, the discriminator outputs remain stable throughout the simulation, with low noise levels. By contrast, SF-RFI exhibits significant variability, indicating reduced accuracy in terms of parameter estimation and an unstable tracking performance owing to interference. Meanwhile, SF-RFI with PB exhibits a notable reduction in noise levels, confirming an improved tracking performance. However, compared with SF-NoRFI, some variability remains, suggesting that the interference mitigation effects of the PB technique are not entirely comprehensive.

The discriminator variance results are directly related to ranging precision. A smaller discriminator variance indicates more accurate ranging estimation, while a larger variance implies increased ranging errors due to noise and interference, which in turn leads to greater positioning errors.

Tables 7 and 8 present the DLL and PLL discriminator variance results for Galileo signals and custom signals that can be tracked. As mentioned earlier, since it was not possible to obtain results for Galileo signals under interference-free conditions, results for the SF-NoRFI scenario are omitted. The results demonstrate that the best ranging precision can be expected in the absence of interference. Furthermore, even in the presence of interference, using the PB method can be expected to yield better ranging precision compared to not using it.

Additionally, Tables 7 and 8 allow us to observe the trend of ranging precision with respect to the satellite’s C/N0. By comparing the C/N0 values in Tables 5 and 6 with the results in Tables 7 and 8, it can be seen that higher satellite C/N0 corresponds to lower discriminator variance values.

Figure 20 shows the IQ diagram and prompt correlator output results. As can be seen in the IQ diagram (Fig. 20(a), SF-NoRFI exhibits I/Q values that are tightly clustered into two distinct circles, indicating stable signal tracking. Conversely, SF-RFI displays a widely dispersed I/Q value distribution, reflecting increased noise levels caused by interference and a significant reduction in bit-determination accuracy. After applying the PB technique to SF-RFI, the dispersion is noticeably reduced, and the distribution closely resembles that of SF-NoRFI, indicating an improved bit-determination accuracy.

As is evident from the prompt correlator outputs (Fig. 20(b)), SF-NoRFI maintains consistent and stable In-phase and Quadrature values throughout the simulation. By contrast, SF-RFI exhibits considerable variability, leading to a decreased bit-determination accuracy. When PB is applied, this variability is substantially reduced, restoring a stability similar to that in an interference-free condition and enhancing the bit-determination performance. However, because multiple samples are removed during the PB process, the power level of the In-phase component is lower than that in the interference-free condition.

These results demonstrate that interference in the L6 band degrades the navigation signal quality, which can significantly affect the actual positioning performance. Figure 21 shows the positioning performance results for the custom signal, and Table 9 summarizes the positioning errors.

Interference in the L6 band severely affects both the navigation signal quality and the position estimation accuracy. For SF-RFI, the root mean squared error (RMSE) is significantly larger than that of both SF-NoRFI and SF-RFI after PB, demonstrating severe degradation caused by interference. Additionally, the time required to achieve the first fix for SF-RFI is approximately 20 s longer than that for SF-NoRFI and SF-RFI after PB. When the PB technique was applied, the RMSE recovered to levels similar to those in the interference-free state. However, if the duration of the interference signals were to increase, the positioning performance would deteriorate even further than the results obtained in this study.

Conclusion

Korea aims to use the L6 band to provide PNT services through a newly developed regional navigation satellite system. However, the L6 band, which accommodates multiple coexisting services, inevitably experiences interservice interference. Therefore, to ensure the stable operation of Korea’s new regional navigation satellite system, it is essential to study the L6 band environment and analyze the potential interference effects on RNSS receivers.

At present, Korea’s regional navigation satellite system is still under development, so it is currently not possible to directly measure the exact signal quality or the resulting positioning errors. To address this limitation, this study proposes a methodology in which interference analysis is conducted by combining real-world L6 band signals with simulated signals that reflect the orbital and signal characteristics of the Korean system, based on publicly available information.

The findings of this study indicate that Korea’s L6 band environment is characterized by persistent, high-power, pulse-type interference signals, which are observable across various locations nationwide. These interference signals have been shown to cause a C/N0 degradation of up to 18 dB in RNSS receivers, significantly deteriorating the signal quality and positioning performance.

Furthermore, the findings of this study confirm that the application of the PB technique can effectively mitigate the impact of interference signals. Following interference removal, the C/N0 degradation of RNSS receivers was reduced to within 1 dB, with a notable recovery in the code delay, Doppler frequency, and phase tracking performance. Considering the widespread occurrence of pulse-type interference in the L6 band, embedding the PB technique into RNSS receivers has been identified as an effective interference mitigation strategy.

However, the interference signals in the L6 band are not exclusively of the pulse type. Additionally, because this study relied on data collected from a single location, its findings may not fully represent the entire service area of the new regional navigation satellite system. Future studies should expand the scope to provide more comprehensive and representative results.

Nonetheless, these findings provide essential insights into the L6 band interference characteristics in Korea and lay the groundwork for advancing the stability and performance of Korea’s new regional navigation satellite system.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Korea Aerospace Research Institute. Satellite Navigation System More Accurately (2023). https://www.kari.re.kr/eng/sub03_08_01.do

Radio Regulations, I. T. U. I. T. U. Articles. International Telecommunication Union, Geneva, Switzerland (2020).

Kim, T. Korean Positioning System (KPS) and Korean Augmentation Satellite System (KASS) update. (2021). https://www.unoosa.org/documents/pdf/icg/2021/ICG15/31.pdf Presented at the Fifteenth Meeting of the ICG, Vienna, Austria (Hybrid Format).

ITU. Calculation method to determine aggregate interference parameters of pulsed RF systems operating in and near the bands 1164–1215 MHz and 1215–1300 MHz that may impact radionavigation-satellite service airborne and ground-based receivers operating in those frequency bands. ITU-R Report M.2220-0 (International Telecommunication Union, 2011).

ITU. Consideration of aggregate radio frequency interference event potentials from multiple Earth exploration-satellite service systems on radionavigation-satellite service receivers operating in the 1215–1300 MHz frequency band. ITU-R Report M.2305-0 (International Telecommunication Union, 2014).

Ministry of Science and ICT. Radio station work and type manual. (2020). https://www.msit.go.kr/bbs/view.do?sCode=user&bbsSeqNo=69&nttSeqNo=2810332

López-Salcedo, J. A., Paonni, M., Bavaro, M. & Fortuny-Guasch, J. C. Compatibility between amateur radio services and Galileo in the 1260–1300 MHz radio frequency band. Issue 1.1, European Commission, Joint Research Centre (2015).

Schütz, A., Kraus, T., Lichtenberger, C. A. & Pany, T. A case study for potential implications on the reception of Galileo E6 by amateur radio interference on German highways considering various transmitter-receiver-signal combinations. In Proceedings of the 34th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS + 2021), 1687–1696 (2021). https://doi.org/10.33012/2021.18026

Mitome, T. & Hayes, D. International committee on GNSS (ICG) working group A compatibility sub group report. In Proceedings of the 9th Meeting of the International Committee on GNSS (ICG), Prague, Czech Republic, 10–14 November 2014. (2014). https://www.unoosa.org/pdf/icg/2014/wg/wga2.4.pdf

Lee, S., Hong, H. J. & Won, J. H. A study on the effects of radio location service on RNSS in the L6-band. In Proceedings of the 36th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS + 2023), 1299–1306 (2023). https://doi.org/10.33012/2023.19249

Skolnik, M. I. Introduction to Radar Systems (1962).

Radio Tutorial. eu. Waves and frequency ranges: https://www.radartutorial.eu/07.waves/Waves%20and%20Frequency%20Ranges.en.html

Forecast International. FPS-117(V)/TPS-77(V): land & sea-based electronics forecast. (2008). https://www.forecastinternational.com/archive/disp_pdf.cfm?DACH_RECNO=165

Lee, S., Han, K. & Won, J. H. Assessment of radio frequency compatibility for new radio navigation satellite service signal design in the L6-band. Remote Sens. 16, 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs16020319 (2024).

Choi, B. K. et al. Performance analysis of the Korean positioning system using observation simulation. Remote Sens. 12, 3365. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12203365 (2020).

Shin, M., Lim, D. W., Chun, S. & Heo, M. B. A study on the satellite orbit design for KPS requirements. J. Position. Navig. Timing. 8, 215–223. https://doi.org/10.11003/JPNT.2019.8.4.215 (2019).

Pany, T. et al. GNSS software-defined radio: history, current developments, and standardization efforts. Navigation 71 https://doi.org/10.33012/navi.628 (2024).

Garcia-Pena, A., Macabiau, C., Julien, O., Mabilleau, M. & Durel, P. Impact of DME/TACAN on GNSS L5/E5a receiver. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Technical Meeting of The Institute of Navigation, 207–221 (2020). https://doi.org/10.33012/2020.17207

Hegarty, C., Van Dierendonck, A. J., Bobyn, D., Tran, M. & Grabowski, J. Suppression of pulsed interference through blanking. In Proceedings of the IAIN World Congress and the 56th Annual Meeting of The Institute of Navigation (2000), 399–408 (2000).

Garcia-Pena, A. et al. Efficient DME/TACAN blanking method for GNSS-based navigation in civil aviation. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS + 2019), 1438–1452 (2019). https://doi.org/10.33012/2019.16993

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the BK21 Four Program funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE, Korea) and National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and J.-H.W.; Methodology, S.L.; Software, S.L.; Validation, S.L. and J.-H.W.; Formal analysis, S.L.; Investigation, S.L. and H.-J.H; Resources, J.-H.W; Data curation, S.L.; Writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; Writing—review and editing, S.L.; Visualization, S.L.; Supervision, J.-H.W; Project administration, J.-H.W; Funding acquisition, J.-H.W.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, S., Hong, HJ. & Won, JH. Assessment of the RFI impact on RNSS receivers in the L6 band for a regional navigation satellite system focused on Korea. Sci Rep 15, 25135 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10363-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10363-w