Abstract

Choroidal vascularity index (CVI) has been extensively used to assess choroidal health in posterior eye disease; however, interpretation is hindered by conflicting evidence on effect of normal physiological factors on CVI. Thus, this review aimed to derive a normative value for CVI and understand its relationship with various normal ocular/image-based factors. Studies were screened for eligibility, defined as eyes with normal ocular parameters (refractive error (RxE) < ± 6 DS, intraocular pressure (IOP < 21 mmHg) and no posterior segment disease and 98 studies were included. Pooled weighted average of subfoveal CVI extracted from healthy eyes (n = 5332 eyes) was 66.50% [CI 65.67–67.32]. Secondary stratifications (time of scan, device wavelength, imaging mode, region of interest, systemic factors) and meta regression (age, RxE and IOP) were insignificant on CVI (p = 0.579–0.872), however Best corrected visual acuity showed positive correlation (p = 0.037). Unaltered, narrow confidence interval in sensitivity analysis, complemented by non-significant publication bias indicated robustness of the synthesised data. These results provide the highest-level evidence in hierarchy of the first normative subfoveal CVI value synthesised from literature and that it is not influenced by most person, eye and imaging factors in healthy eyes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The choroid is the most vascularised structure of the eye and plays a crucial role in blood supply and metabolic support of the outer retina1, thermoregulation, ocular accommodation anteriorly, and modulation of scleral growth2. Not surprisingly, structural and function alterations in the choroid are considered to have a primary role in ocular diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD)3, diabetic chorioretinopathy4 polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV)5, myopia6 and uveitis7. Assessing choroidal vascular health is thus is a key factor in understanding early ocular disease and ensuring appropriate disease monitoring.

The choroidal vascularity index (CVI) is a non-invasive measure of choroidal vascularity that is based on the ratio of the vascular area (LA) to the total choroidal area (TCA) from binarized image. CVI has been applied to numerous vascular diseases8 and found critical clinical insights including early detection of AMD9, glaucoma10, diabetes mellitus11 and central serous chorioretinopathy12. Population studies who explored this tool in normal healthy participants however are, either assessing only ethnically homogenous samples13, or lacking critical details in their definition of healthy population such as refractive error/axial length criteria or including participants with non-macular diseases14. The reported associations of normal physiological factors such as age are also conflicting wherein some studies show no effect15,16,17 while others showing varying age-related associations18,19,20. Likewise associations between axial length6,21, and diurnal variation to CVI are also conflicting22,23,24. Together, poor understanding of the normative range for CVI limits its clinical application as it is difficult to confirm if alterations in CVI in ocular disease are due disease pathology or just physiological variations.

Thus, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to compile and analyse the accumulated literature on CVI to determine

-

1.

the pooled average normative choroidal vascularity index value in healthy individuals without posterior segment disease and,

-

2.

the person, image and eye-specific factors that significantly influence this measure

By synthesising the highest level of evidence in research hierarchy, i.e. systematic review and meta-analysis, this study will provide essential baseline values that enhance the clinical applicability of CVI, improve its reliability as a biomarker for choroidal vascular health, and pave the way for future research in ocular disease assessment.

Results

Selection of studies

The electronic database search initially yielded 359 studies which was reduced to 197 studies after screening for title and abstract. Ninety-nine studies were further excluded after full text screening for reasons including wrong population, different method of CVI calculation, unclear inclusion criteria, paediatric population and wrong outcome (full list of reasons for exclusion in Supplementary Table 1). A total of 98 unique studies were eligible for the final review and meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics and quality assessment

A detailed summary of all included studies is presented in Supplementary Table 2. All included studies were observational and cross-sectional in nature: 83 studies were case–control studies, and 15 studies were cross-sectional based either on assessment of healthy participant characteristics (effect of wearing masks, valvalsa manoeuvre on CVI, n = 6) or assessing CVI methodology in healthy subjects (differences in OCT machines, using AI for measurement of CVI etc., n = 8). The majority of studies were conducted in Turkey (42/98)16,19,21,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63 followed by the UK (14/98)20,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76, India (10/98)77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86, China (9/98)87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95, United stated (8/98)96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103, Singapore (5/98)11,13,104,105,106, Korea (5/98)4,10,107,108,109, Iran (2/98)110,111, Tokyo (1/98)112 and Australia (1/98)18. Sample size ranged from 6 to 345 eyes and average age of participants ranged from 22 to 77 years. Statements about funding and conflicts of interests are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

All the publication factors were reviewed for quality assessment. Most studies (91/98) had at least one section of high risk of bias (Supplementary Table 4). For the section, “Representative of the cohort”, 93% of the studies displayed high risk by having non-consecutive recruitment for the extracted group while 7% of studies recruited consecutive patients displaying low risk. For “Selection of the controls”, 4% of studies recruited the extracted group from the community and 72% recruited the group from a university or hospital population displaying low to moderate risk while 22% of studies did not provide adequate descriptions to determine a classification. In the section, “Definition of controls”, 82% of the control population had no history of disease indicating low risk, while 22% had an inadequate description of presence or absence of disease and were simply termed as healthy population displaying unclear risk. For the section “Ascertainment of exposure”, 72% of the studies had a prospective study design, and 25% had a retrospective study design displaying low risk. One study had an inadequate description of the study design indicating unclear risk.

Quantitative assessment

Primary outcome (CVI)

All 98 studies were included in the primary meta-analysis. The pooled weighted average of subfoveal CVI of normal, healthy eyes (n = 5332 eyes) was 66.50% [CI 64.85–68.15] with a prediction interval of 58.28–74.24% representing the moderate heterogeneity of the data (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 1).

Primary outcome stratifications

Data from 98 studies were collated to analyse the relationship of categorical image-level factors such as OCT device used, OCT imaging mode, time of day scan was taken and region of interest and individual level factors such as presence of systemic disease to CVI (Fig. 2).

Person-level factors

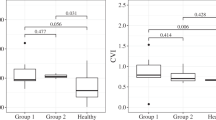

Presence of systemic disease

CVI was not significantly different between the 43 studies (n = 1933 eyes) that specified the absence of systemic disease in their population (67.08% [65.74–68.42%]) versus the 4 studies (n = 232 eyes) that reported a presence of systemic disease (diabetes/hypertension; 65.95% [64.13–67.76%], p = 0.62). Fifty-one studies (n = 3167 eyes) did not specify the presence or absence of systemic disease in a clear manner and were excluded from this stratification.

Image level factors

OCT device and scanning wavelength

All 98 studies reported the specific OCT devices used. Devices were then classified as longer wavelength OCT (1050 nm; i.e. Swept Source OCT DRI-OCT Triton OCT Topcon and VG200S; SVision Imaging, Henan, China, n = 17 studies, 533 eyes) or standard wavelength OCT devices (670–870 nm, Spectralis, Heidelberg Engineering GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany, Cirrus HD-OCT 5000, standard, Zeiss Cirrus, Topcon OCT-1000 Mark II, Software Version 4.21; Topcon Corp SD OCT Enhanced Depth Imaging mode, RTVue-XR Avanti, Optovue Inc., Fremont, CA, USA SD OCT, n = 81 studies, 4799 eyes). These devices have been shown to have good repeatability for choroidal measurements93,113,114,115,116,117,118. Weighted average of CVI from longer wavelength OCTs was 65.11% [63.24–66.98%] while weighted average of CVI of standard wavelength OCTs was slightly higher at 66.78% [65.88–67.69%]. The group effect size (θ) was individually significant (p = 0.000) however the overall group difference was statistically not significant (p = 0.11).

Time of scan (diurnal variation)

Forty-nine studies reported the time at which the OCT scan was acquired. Studies performed during ante meridiem (AM) (33 studies, 1595 eyes) has an average CVI of 66.77% [65.40–68.14%] which was not significantly different to those performed post meridiem (PM) (13 studies, 554 eyes) with CVI of 66.56% ([63.53–69.47%], p = 0.90). Three studies (211 eyes) reported time ranging from morning to evening and were not considered for this analysis.

Imaging mode

Sixty-five studies (n = 3751) used enhanced depth imaging (EDI) mode for capturing OCT B scans while 33 studies (1581 eyes) used the standard mode of imaging. CVI was higher for studies performed in EDI mode (67.00% [66.00–68.00%]) versus standard mode (65.60% [64.10–66.90%]) with the group θ individually significant (p = 0.00) but overall group difference not being statistically significant (p = 0.09).

Combination of OCT and imaging mode

Sixteen studies (507 eyes) used long wavelength OCT with standard imaging mode and reported CVI to be 65.18 ([63.13–67.23%], p = 0.00), while only one study reported using EDI mode (26 eyes) and the CVI to be 66.55 ([65.90–67.20%]). Similarly, studies using standard wavelength OCT with standard imaging mode (n = 17, 1074 eyes) reported CVI to be 65.95 ([63.70–68.09%], p = 0.00), while those who used EDI mode (n = 64, 3725 eyes) had a CVI value of 67.02 ([66.0–68.05%], p = 0.00). However, the overall group effect was not significant (p = 0.33).

Region of interest

All the studies defined the exact area over which CVI was quantified. Forty studies (n = 2196 eyes) calculated CVI within 1–2 mm of the fovea and reported a value of 66.45% [65.21–67.70%] while nine studies (n = 483 eyes) calculated CVI within 2–3 mm of the fovea, reporting a value of 68.59% [65.21–71.96%] and forty-nine studies (n = 2653 eyes) assessed an area of 3 mm up to the full scan area (~ 6–12 mm) and reported a CVI of 66.12% [65.65–67.32%]. The group difference in CVI was not significant between area sub-groups (p = 0.40).

Overall stratification

When assessed individually, the above factors didn’t show significant association with CVI, however when all the factors were analysed together, the adjusted CVI from twenty-four studies is 67.48% [65.80–69.30%] with the prediction interval ranging from 58.42 to 76.54%. The group difference was significant (p = 0.00, Fig. 2).

Meta regression

Data from 17 studies were collated for meta-analysis to analyse the relationship of continuous person level factors such as age, and eye-level factors such as axial length, BCVA, and IOP to CVI. Individually, these factors showed no association, however when all continuous person- and eye-level factors were tested together, BCVA showed a positive correlation with CVI within the specified normal limit of vision (Table 1).

Correlation with choroidal thickness:

CVI was found to form a weak linear relationship with choroidal thickness (n = 78, Mean CT: 285.5 ± 61.52 microns, Y = 2.778x + 101.9, R2 = 0.041) (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to validate the primary outcome measure by adjusting specific circumstances such as exclusion of suspected shared populations and exclusion of studies which included both eyes in their sample size. The results revealed robustness of the data whereby neither the primary pooled weighted mean nor the prediction interval was not significantly altered (p = 0.69–0.91).

Publication bias

Galbraith plot of the primary outcome demonstrated that 96% of the data fell within the 95% confidence interval estimation indicating low publication bias (Fig. 3).

GRADE assessment and summary of findings

The GRADE assessment concluded that the evidence from the collective studies in this review have moderate confidence that the described pooled weighted mean from the primary outcome is as stated (Supplementary Table 5).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis found the weighted average CVI of a normal healthy population to be 66.50 ± 1.65% and independent of most person- and eye-level factors such as age, axial length, refractive error, and intraocular pressure when within a healthy range. When adjusted for image level factors, the pooled CVI increased to 67.48 ± 3.5% but device related variations such as area of measurement, excitation wavelength, imaging mode or time of day of scan had no significant influence. This review suggests that CVI is indeed a robust choroidal marker and could be compared against populations of healthy eyes even with variations in demographic or image acquisition characteristics.

This study found normal CVI was 66.5% suggesting almost two-thirds of the subfoveal choroid of healthy individuals is vascular lumen versus stromal tissue. This is similar to the estimates from post mortem eyes which report the vascular area of the choriocapillaris in the submacular region of normal eyes to be 51–80%119,120 (variation due to differences in study population, tissue processing, staining methodology and quantification methods). These findings are also consistent with reports of choroidal vessel density of healthy eyes using alternative analysis methods for OCT scans121 and choriocapillaris vascular density from more recent OCTA studies of normal healthy eyes (76–84%)122,123,124,125. Given that human choroid is reported to have the highest vascularity per unit weight126, this corresponds to the high luminal area vs stromal area reflected in CVI measurement ranges from 64 to 68.15% in a healthy population.

We did not observe a difference between CVI calculated from images acquired using “standard” wavelength (680–890 nm) and “longer” wavelength OCT (1050 nm). This contrasts previous studies that hypothesised that longer wavelength OCTs might provide more accurate CVI calculations because of increased choroidal visualisation due to deeper penetration and improved separation of lumen and stromal tissue127. We also did not find any effect of scan mode on CVI neither did combining OCT and imaging mode despite EDI mode being reported to increase choroidal visibility due to placement of the zero delay line8. The lack of impact from wavelength and scan mode could have been influenced (1) by device with most included studies (n = 63/98) using Spectralis OCT which already improves image resolution compared to standard wavelength OCT through differences in optics rather than wavelength128,129. Alternatively, in the process of binarization, the entire image is converted to absolute values of black and white, unifying subtle changes (2) considering imaging parameters that influence choroidal visibility such as the position of the zero delay line and the use of EDI are end-user dependent130, this may be an issue as 28/98 studies were retrospective and the intent of OCT capture could not be determined with certainty and lastly (3) the longer wavelength does indeed enhance the choroidal visibility, and that it does so equally for white and dark zones within the choroid, hence maintaining the proportionality within “the normal spectrum”. In a disease state, perhaps longer wavelenght might be better detect subtle changes in deeper choroid, additional research may be necessary to validate these findings. Studies utilising other imaging devices/modalities with lower resolution or studies with disease spectrum should take caution as the findings may not apply to them.

We also found no association between the time of day the scan was acquired and CVI despite choroidal circulation metrics being shown to undergo significant changes with the time of measurement131. Alanazi et al.22 and Kinoshita et al.23 previously reported changes in CVI within the same day but disagreed on the contributor to this variation (stromal vs non stromal). On the other hand, Singh et al.24 reported that the CVI of the temporal quadrant is impacted by diurnal variation while, macular CVI and other subfields are not. In this review, only 50% of included studies reported the time of day of scan acquisition and variability in reporting only allowed us to stratify studies into AM and PM. Thus, while no significant diurnal variation effect was found for CVI of healthy eyes, this may be due to the coarseness of categorisation and the incomplete data set. Future work is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

When all continuous eye-level factors were meta regressed together (IOP, refractive error, axial length, BCVA), only BCVA was significantly associated with CVI. BCVA has been shown to have linear correlation with CVI88,132,133. This is not surprising, given that cone-mediated vision has greater metabolic demands and requires at least a 15% higher choroidal blood flow compared to rod-mediated vision134,135, suggesting the use of CVI as an adjunctive test to monitor vision changes or disease progression. Although CVI is structural measure, there may be differences in hemodynamics which cannot be adequately characterised by CVI, flow changes can result in vasculature remodelling136 which can be reflected in CVI. Intraocular pressure, refractive error and axial length have previously been associated with CVI but this only appears to be relevant when these parameters are within the pathological range. For example, several studies have reported reduced CVI in myopia i.e. correlation between refractive error/axial length and CVI25,84,137,138. However, studies of refractive error within normative ranges (such as less than ± 6 diopters) have found no associations13,15,21,37. Wang et al.132 proposed a threshold where associations between refractive error and CVI are only observed above an axial length of 27.26 mm highlighting the complexity in the relationship. Thus, while CVI appears to be resistant to several ocular parameters, this effect appears to be only applicable within normative ranges and must be treated with caution with individual considerations.

Person-level factors such as including age, and systemic vascular diseases were not associated with CVI in healthy eyes when controlled for other factors. The literature indicates presence of diabetes mellitus4,139, hypertension27 and or cardiovascular disease140 impacts CVI. Although, a higher CVI was found in the absence of these conditions in this review, it did not reach statistical significance warranting further research. There has been a large amount of conflicting evidence regarding associations between age and CVI with several studies reporting a loss of CVI with age18,19,20,84,85,137,141 and others reporting no association13,15,16,17,77,105. Other OCT based choroidal parameters such as choroidal thickness normally decreases with age142,143,144,145 and evidence from post mortem studies strongly suggest the choroid undergoes thinning, choriocapillaris density decrease, vessel stenosis, loss of elasticity and composition changes in Bruch’s membrane with aging146,147,148. The choroidal area parameters that constitute CVI (TCA, LA and SA) also show age-related loss15,18. The null effect of age on CVI in this review suggests that a decline in luminal and choroidal area is proportional, at least in healthy eye17,41. This is supported by work of Ramrattan et al.146 who showed a linear decrease in capillary diameter and capillary density alongside total choroidal thickness over 10 decades of life. While we definitively cannot dimmish the findings of age association with CVI, this review provides highest evidence in hierarchy that under healthy considerations of BCVA, refractive error, IOP, axial length and limited systemic vascular related disease, CVI does not show association with age. As with imaging factors, these results should be interpreted with caution in disease populations with age-related diseases such as age-related macular degeneration where longitudinal changes in CVI have been reported149.

The main limitation in this review was the large number of studies were excluded because the candidate population was a control group within a case–control design that was poorly defined. These potential populations could not be adequately screened against our inclusion/exclusion criteria. Although, the risk of bias indicates a high score, we don’t believe that this limits the results. This is because of the nature of recruitment for control group, where in description of details is limited unlike the disease group. Studies which utilised alternative CVI methodology such as that described by Sonoda et al.150, were also excluded from this review to have consistent methodology. The field has evolved since the describe methodology and the method describe by Agrawal et al.151 is being predominantly used. Ocular magnification is known to play a significant role in structural components such as thickness and individual elements like total choroidal area, luminal area, stromal area. However CVI is a ratio of these structural measures and designed to mitigate inter-individual differences such as the effect of ocular magnification15. A study with similar transverse measurement indicated the corrected difference to be clinically insignificant152. Hence we believe the results to be unhampered in its application. The included studies also had poor reporting of factors such as ethnicity which could not be subsequently explored in meta-analyses. Despite this, a sample of 5332 eyes from 98 studies were included in the final meta-analysis and the effect of device wavelength, diurnal variation, imaging modality, region of interest, systemic vascular-related disease, age, axial length, refractive error, and IOP assessed in sub-analyses. The narrow prediction value and GRADE assessment further indicated that the synthesised data was robust. To the authors knowledge, at present CVI is not available as a metric on any commercial OCT software interfaces and requires external software/platforms for its calculation, limiting its use in clinical practice. However, the normative values of this review (alongside evidence that CVI is a robust biomarker of choroidal health against numerous physiological parameters) should help towards its potential integration into commercial platforms in the future.

Conclusion

This review found average subfoveal CVI for healthy normal eyes is 66.50% (64.85–68.15%) and is independent of age, IOP and axial length when these factors are within a normative range. CVI was also independent of diurnal variation, excitation wavelength of the device, region of interest and the imaging mode used. Based on the findings from studies forming this review, we have a moderate certainty in GRADE assessment, good confidence interval, low publication bias and low to moderate heterogeneity. These findings highlight that despite the methodological differences in CVI quantification, the metric is resistant to most person, eye and image-level factors and therefore a bust measure of in vivo choroidal angioarchitecture.

Methods

This systematic review adhered to the guidelines of the preferred reporting items for systemic reviews and meta analyses statement (PRISMA)153,154 and was prospectively registered on Prospero155 (CRD42022377271) without amendments.

Eligibility criteria and literature search

The inclusion criteria were studies which presented the CVI of at least one, adult participant group with normal ocular health which was defined as:

-

Age above 18 years,

-

Absence of any ocular disease of the posterior pole (including but not limited to optic nerve head),

-

Refractive error (RxE) less than ± 6 D spherical equivalent and/or axial length between or equal to 22–26 mm and,

-

Intraocular pressure less than ± 21 mmHg.

Studies were included only if they calculated CVI based on methodology of Agrawal et al.151 which is considered the common protocol of the field. This was determined by either citation of the method or description commensurate with Agrawal et al. including marking the choroid as a region of interest of an OCT B scan, and binarizing the image using Niblack’s auto thresholding method then extracting CVI as ratio of dark pixels (Luminal Area) to total pixels (Total choroidal area). Exclusion criteria included:

-

Paediatric populations,

-

Calculation of CVI using alternative methodology150 (e.g. Sonoda et al.) or

-

Studies with unclear/inadequate descriptions of the study population to determine if they met the inclusion criteria.

The presence of systemic vascular diseases was documented but not used as a criterion for exclusion.

The research question was framed using the PICO framework156 and the key search terms were determined prior to the literature search. These keywords were searched on electronic databases of PubMed and Embase for all published articles from inception to September 2022 to ensure adequate coverage of the literature. Given the relative novelty of this research area, search with MeSH terms was inconclusive. Instead, alternate terms for choroidal vascularity index were incorporated with Boolean operator in the text field. All subheadings were included in the search. Published journals were limited to English journals. Review articles and conference proceedings were excluded due to data limitations and initial search was compiled in Microsoft excel version 2402 (Microsoft Corporation, USA) reported in Supplementary Table 6.

Study selection

Two independent reviewers (MK and LNS) screened all unique studies for title/abstract. Duplicates and ineligible studies were manually removed, and full text articles of potentially eligible studies were uploaded onto the Covidence website (Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org) for independent full text screening. Disagreements in any stages were resolved through discussion and consensus.

Data synthesis

Data synthesis was performed by a single grader (MK) from the selected studies in Covidence. Quantitative data collected included the primary outcome measure of CVI expressed as a percentage or ratio from the control/non-intervention arm of the study. Person-level factors including age, and presence of systemic disease; image-level factors including OCT device model and scanning wavelength, imaging mode used, time of day scan was taken, and diameter of region of interest that CVI was calculated and eye-level factors including axial length, refractive error, best corrected visual acuity and intraocular pressure and was also extracted from all studies. (Detailed list of factors in Supplementary Table 7).

Data items and quality assessment

Extracted data fields included publication details such as author list, country of publication, publication date, study design, funding sources, and conflicts of interest. The risk of bias assessment was performed using a modified version of Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Non-Randomized studies in Meta-Analyses157 by 2 authors (MK and LNS) independently within Covidence (Supplementary Table 8).

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analysis of the data was performed using STATA 18.0 (StataCorp LLC, Texas, USA). Since CVI can be reported as raw measure (ratio) or converted to a percentage, all the reported ratio measures of CVI were converted into percentage for homogeneity. Primary metanalysis was performed by calculation of pooled weighted average (weighted by standard error) using the inverse variance method and the random effects REML model was chosen to provide distribution of true effect sizes due to heterogeneity between studies throughout the analysis158. The heterogeneity was evaluated using the prediction interval rather than I2 statistics, to provide a more robust measure in pooled mean outcomes159. To assess the influence of personal factors and image based factors, sub group analysis and meta regression were performed respectively if more than 10 studies had data availability and their results were represented with forest plots. Publication bias was assessed using a Galbraith plot and confirmed with Egger regression and Begg and Mazumder rank correlation. Sensitivity analysis was performed to validate the findings from this study by

-

(a)

Including and excluding studies with repeated populations, and

-

(b)

Including and excluding studies with both eyes included in the sample size

Repeated populations were referred to as studies which used the same sample population as indicated by their description of similar sample size and location or explicitly stating of recruitment from specific registry or population cohort. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The overall quality assessments were expressed as percentage of low/high risk of bias. The summary of evidence was validated through GRADE assessment160,161.

Data availability

The dataset generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Foulds, W. S. The choroidal circulation and retinal metabolism—An overview. Eye 4, 243–248 (1990).

Nickla, D. L. & Wallman, J. The multifunctional choroid. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 29, 144–168 (2010).

Farazdaghi, M. K. & Ebrahimi, K. B. Role of the choroid in age-related macular degeneration: A current review. J. Ophthalmic Vis. Res. 14, 78–87 (2019).

Kim, M., Ha, M. J., Choi, S. Y. & Park, Y. H. Choroidal vascularity index in type-2 diabetes analyzed by swept-source optical coherence tomography. Sci. Rep. 8, 70 (2018).

Sen, P., Manayath, G., Shroff, D., Salloju, V. & Dhar, P. Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: An update on diagnosis and treatment. Clin. Ophthalmol. 17, 53–70 (2023).

Liu, Y., Wang, L., Xu, Y., Pang, Z. & Mu, G. The influence of the choroid on the onset and development of myopia: From perspectives of choroidal thickness and blood flow. Acta Ophthalmol. (Copenh.) 99, 730–738 (2021).

Thapa, S., Kharel, R. & Shrestha, J. B. Role of choroidal thickness assessment in unilateral acute anterior uveitis. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 68, 1869–1874 (2020).

Agrawal, R. et al. Exploring choroidal angioarchitecture in health and disease using choroidal vascularity index. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 77, 100829 (2020).

Sacconi, R. et al. Choroidal vascularity index in different cohorts of dry age-related macular degeneration. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 10, 26 (2021).

Park, Y. & Cho, K. J. Choroidal vascular index in patients with open angle glaucoma and preperimetric glaucoma. PLoS ONE 14, e0213336 (2019).

Tan, K.-A. et al. Choroidal vascularity index—A novel optical coherence tomography parameter for disease monitoring in diabetes mellitus?. Acta Ophthalmol. (Copenh.) 94, e612–e616 (2016).

Ruiz-Moreno, J. M. et al. Choroidal vascularity index versus choroidal thickness as biomarkers of acute central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmic Res. 66, 627–635 (2023).

Agrawal, R. et al. Choroidal vascularity index as a measure of vascular status of the choroid: Measurements in healthy eyes from a population-based study. Sci. Rep. 6, 21090 (2016).

Mori, Y. et al. Distribution of choroidal thickness and choroidal vessel dilation in healthy Japanese individuals: The Nagahama study. Ophthalmol. Sci. 1, 100033 (2021).

Kumar, M. et al. Age related grid-wise spatial analysis of choroidal parameters in well characterised healthy population. Sci. Rep. 14, 26592 (2024).

Aksoy, M., Simsek, M. & Apaydin, M. Evaluation of choroidal circulation and stromal features in Graves’ disease. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 32, 1680–1686 (2022).

Zhou, H. et al. Age-related changes in choroidal thickness and the volume of vessels and stroma using swept-source OCT and fully automated algorithms. Ophthalmol. Retina 4, 204–215 (2020).

Nivison-Smith, L. et al. Normal aging changes in the choroidal angioarchitecture of the macula. Sci. Rep. 10, 10810 (2020).

Kocak, N., Subasi, M. & Yeter, V. Effects of age and binarising area on choroidal vascularity index in healthy eyes: An optical coherence tomography study. Int. Ophthalmol. 41, 825–834 (2021).

Damian, I., Roman, G. & Nicoara, S. D. Analysis of the choroid and its relationship with the outer retina in patients with diabetes mellitus using binarization techniques based on spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. J. Clin. Med. 10, 210 (2021).

Karasu, B. & Celebi, A. R. C. Choroidal vascularity index: An enhanced depth optical coherence tomography-based parameter to determine vascular status in patients with proliferative and non-proliferative macular telangiectasia. Int. Ophthalmol. 41, 3505–3513 (2021).

Alanazi, M. K. Within-day changes in luminal, stromal choroidal thickness, and choroidal vascularity index in healthy adults. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 71, 166–173 (2023).

Kinoshita, T. et al. Diurnal variations in luminal and stromal areas of choroid in normal eyes. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 101, 360–364 (2017).

Singh, S. R. et al. Diurnal variation in subfoveal and peripapillary choroidal vascularity index in healthy eyes. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 67, 1667–1672 (2019).

Alis, M. G. & Alis, A. Choroidal vascularity index in adults with different refractive status. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 36, 102533 (2021).

Altinel, M. G., Uslu, H., Kanra, A. Y. & Dalkilic, O. Effect of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome and continuous positive airway pressure treatment on choroidal structure. Eye (London) 36, 1977–1981 (2022).

Asikgarip, N., Temel, E., Kivrak, A. & Ornek, K. Choroidal structural changes and choroidal vascularity index in patients with systemic hypertension. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 32, 2427–2432 (2022).

Asikgarip, N., Temel, E. & Ornek, K. Assessment of choroidal vascularity index during the menstrual cycle. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1177/11206721211057685 (2021).

Balci, S. & Turan-Vural, E. Evaluation of changes in choroidal vascularity during acute anterior uveitis attack in patients with ankylosing spondylitis by using binarization of EDI-optical coherence tomography images. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 31, 101778 (2020).

Balci, S., Ozcelik Kose, A. & Yenerel, N. M. The effect of optic neuritis attacks on choroidal vascularity index in patients with multiple sclerosis. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 259, 2413–2424 (2021).

Balci, A. S., Pehlivanoglu, S., Basarir, B. & Altan, C. Comparison of retinal and choroidal changes in Fuchs’ uveitis syndrome. Int. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-022-02595-w (2022).

Bayram, N., Gundogan, M., Ozsaygili, C. & Adelman, R. A. Posterior ocular structural and vascular alterations in severe COVID-19 patients. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 260, 993–1004 (2022).

Ceri, M. et al. Ocular changes in nephrotic syndrome patients with preserved renal functions. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 39, 103024 (2022).

Cevher, S., Ucer, M. B. & Sahin, T. How does anisometropia affect the choroidal vascularity index?. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 70, 2043–2049 (2022).

Ceylanoglu, K. S., Eser, N. A. & Sen, E. M. Choroidal structural evaluation in inactive Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 39, 103012 (2022).

Durusoy, G. K. & Gumus, G. Choroidal changes due to long-term use of N95 face masks. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 35, 102447 (2021).

Guler Alis, M. & Alis, A. Choroidal vascularity index in adults with different refractive status. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 36, 102533 (2021).

Hepokur, M. et al. Long-term follow-up of choroidal changes following COVID-19 infection: Analysis of choroidal thickness and choroidal vascularity index. Can. J. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjo.2021.06.020 (2021).

Inam, O., Arat, Y. O., Yavas, G. F. & Arat, A. Retinal and choroidal optical coherence tomography findings of carotid cavernous fistula. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 206, 264–273 (2019).

Isik, B., Ersoz, M. G. & Ofluoglu, M. S. Choroidal structural changes in airline pilots and cabin crew. Int. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-022-02580-3 (2022).

Kocak, N., Yeter, V., Subasi, M., Yucel, O. E. & Can, E. Use of choroidal vascularity index for choroidal structural evaluation in smokers: An optical coherence tomography study. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 39, 298–303 (2020).

Kocak, N., Beldagli, C. & Yeter, V. Acute effects of coffee on peripapillary and subfoveal choroidal parameters in young healthy subjects. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 32, 3584–3591 (2022).

Ozcaliskan, S., Balci, S. & Yenerel, N. M. Choroidal vascularity index determined by binarization of enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography images in eyes with intermediate age-related macular degeneration. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 30, 1512–1518 (2020).

Ozcan, G. et al. Choroidal vascularity index in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Breath https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-021-02538-2 (2021).

Ozcelik-Kose, A., Balci, S. & Turan-Vural, E. In vivo analysis of choroidal vascularity index changes in eyes with Fuchs uveitis syndrome. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 34, 102332 (2021).

Ozcelik-Kose, A. et al. Effect of bariatric surgery on macular and peripapillary choroidal structures in young patients with morbid obesity. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 57, 370–375 (2022).

Ozer, M. D., Batur, M., Tekin, S., Seven, E. & Kebapci, F. Choroid vascularity index as a parameter for chronicity of Fuchs’ uveitis syndrome. Int. Ophthalmol. 40, 1429–1437 (2020).

Sekeryapan Gediz, B., Corak Eroglu, F., Aydogan, M., Aydugan, M. T. & Kilinc Hekimsoy, H. Choroidal vascular changes in acne patients under isotretinoin treatment. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 40, 125–129 (2021).

Sevik, M. O., Cam, F., Aykut, A., Dericioglu, V. & Sahin, O. Choroidal vascularity index changes during the Valsalva manoeuvre in healthy volunteers. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 42, 367–375 (2022).

Simsek, M., Aksoy, M. & Ulucakoy, R. K. Evaluation of retinal and choroidal microcirculation in Behcet’s disease. Eye (London) 36, 1494–1499 (2022).

Simsek, M., Inam, O., Sen, E. & Elgin, U. Analysis of the choroidal vascularity in asymmetric pseudoexfoliative glaucoma using optical coherence tomography-based image binarization. Eye (London) 36, 1615–1622 (2022).

Temel, E. et al. Choroidal vascularity index and retinal nerve fiber layer reflectivity in newly diagnosed migraine patients. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 36, 102531 (2021).

Temel, E. et al. Analysis of choroidal vascularity index in multiple sclerosis patients without optic neuritis attack. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 38, 102823 (2022).

Temel, E., Kocamis, O., Asikgarip, N., Ornek, K. & Arioz, O. Evaluation of choroidal thickness and choroidal vascularity index during pregnancy. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 56, 237–243 (2021).

Temel, E. et al. Choroidal structural alterations in diabetic patients in association with disease duration, HbA1c level, and presence of retinopathy. Int. Ophthalmol. 42, 3661–3672 (2022).

Temel, E., Asikgarip, N., Ornek, K. & Kivrak, A. Short-term effect of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor on choroidal vascularity. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 36, 102569 (2021).

Topcuoglu, M. & Aslan, F. Evaluation of the effect of a novel beta3-adrenergic agonist on choroidal vascularity. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 62, 17 (2021).

Ucgul Atilgan, C., Hondur, G. & Citirik, M. Peripapillary and macular structural and vascular parameters in age-related choroidal atrophy. J. Glaucoma 32, 19–26 (2023).

Uslu, H. & Altinel, M. G. Comparison of the choroidal structural components and choroidal vascularity index between patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and healthy controls. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 36, 102570 (2021).

Yildiz, M. B., Balci, S., Ozcelik Kose, A., Yenerel, N. M. & Yildiz, H. E. Retinal and choroidal vascularity changes in healthcare professionals wearing FFP3 respirators. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 40, 70–77 (2021).

Yilmaz, M., Polat, O. A., Karayigit, D. Z. & Ayyildiz, T. Choroidal vascularity index and choroidal thickness changes in patients with allergic asthma. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 36, 102494 (2021).

Yeter, V., Kocak, N., Subasi, M. & Parlak, U. Choroidal vascularity index in thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. Can. J. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjo.2021.06.023 (2021).

Ersoz, M. G. et al. Repeatability of choroidal vascularity index measurements using directional optical coherence tomography images. Retina 41, 1723–1729 (2021).

Bousquet, E. et al. Choroidal structural changes in patients with birdshot chorioretinopathy. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 29, 346–351 (2021).

De Bernardo, M. et al. Choroidal structural evaluation in celiac disease. Sci. Rep. 11, 16398 (2021).

Giannaccare, G. et al. Choroidal vascularity index quantification in geographic atrophy using binarization of enhanced-depth imaging optical coherence tomographic scans. Retina 40, 960–965 (2020).

Iovino, C. et al. Effects of different mydriatics on the choroidal vascularity in healthy subjects. Eye 35, 913–918 (2021).

Iovino, C. et al. Influence of protocol scan on choroidal vascularity measurements: A spectralis optical coherence tomography study. Eye (London) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-022-02255-4 (2022).

Krytkowska, E. et al. The impact of vascular risk factors on the thickness and volume of the choroid in AMD patients. Sci. Rep. 11, 15106 (2021).

Loiudice, P. et al. Choroidal vascularity index in thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy: A cross-sectional study. Eye Vis. (Lond.) 8, 18 (2021).

Parisi, V. et al. Macular functional and morphological changes in intermediate age-related maculopathy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 61, 11–11 (2020).

Pellegrini, M. et al. Choroidal vascular changes in arteritic and nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 205, 43–49 (2019).

Sacconi, R. et al. Choroidal vascularity index in leptochoroid: A comparative analysis between reticular pseudodrusen and high myopia. Eye (London) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-021-01889-0 (2022).

Scarinci, F., Patacchioli, F. R., Costanzo, E. & Parravano, M. Relationship of choroidal vasculature and choriocapillaris flow with alterations of salivary alpha-amylase patterns in central serous chorioretinopathy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 62, 19 (2021).

Sidorczuk, P., Obuchowska, I., Konopinska, J. & Dmuchowska, D. A. Correlation between choroidal vascularity index and outer retina in patients with diabetic retinopathy. J. Clin. Med. 11, 3882 (2022).

Viggiano, P. et al. Choroidal structural changes in different intermediate AMD patterns. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 32, 460–467 (2022).

Agarwal, A. et al. Choroidal structural changes in tubercular multifocal serpiginoid choroiditis. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 26, 838–844 (2018).

Agarwal, A. et al. Effect of weight loss on the retinochoroidal structural alterations among patients with exogenous obesity. PLoS ONE 15, e0235926 (2020).

Agrawal, R. et al. Choroidal structural changes in sympathetic ophthalmia on swept-source optical coherence tomography. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 29, 537–542 (2021).

Dave, T. V., Jonnadula, G. B., Lanka, P., Natarajan, R. & Dave, V. P. Choroidal vascularity index in thyroid eye disease: Comparison with controls and application in diagnosing non-inflammatory active disease. Orbit 41, 89–96 (2022).

Magesan, K., Sachidanandam, R., Verma, A. & Biswas, J. Retino-choroidal evaluation of the macular region in eyes with tubercular serpiginous-like choroiditis using swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography. Int. Ophthalmol. 42, 2651–2664 (2022).

Shrivastav, A. et al. Choroidal microvascular alterations in COVID-19 patients. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 31, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/09273948.2022.2062387 (2022).

Tan, R. et al. Choroidal vascularity index in retinitis pigmentosa: An OCT study. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retina 49, 191–197 (2018).

Wei, X. et al. Comparison of choroidal vascularity markers on optical coherence tomography using two-image binarization techniques. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 59, 1206–1211 (2018).

Wei, X. et al. Choroidal structural analysis and vascularity index in retinal dystrophies. Acta Ophthalmol. (Copenh.) 97, e116–e121 (2019).

Wei, X. et al. Optical coherence tomography-based choroidal structural analysis and vascularity index in best vitelliform macular dystrophy. Ophthalmol. Ther. 11, 2141–2152 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Choroidal morphologic and vascular features in patients with myopic choroidal neovascularization and different levels of myopia based on image binarization of optical coherence tomography. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 8, 791012 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Vascular changes of the choroid and their correlations with visual acuity in pathological myopia. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 63, 20–20 (2022).

Wang, Y. M. et al. Characterization of macular choroid in normal-tension glaucoma: A swept-source optical coherence tomography study. Acta Ophthalmol. (Copenh.) 99, e1421–e1429 (2021).

Bakthavatsalam, M. et al. Choroidal structures in polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy, neovascular age-related maculopathy, and healthy eyes determined by binarization of swept source optical coherence tomographic images. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 255, 935–943 (2017).

Liu, S. et al. The choroidal vascularity index decreases and choroidal thickness increases in Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease patients during a recurrent anterior uveitis attack. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 26, 1237–1243 (2018).

Ma, J., Niu, H., Ma, X., Han, C. & Qu, Y. Effects of long-term high-altitude exposure on retinal and choroidal microcirculation. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 260, 3525–3532 (2022).

Wu, H. et al. Assessment of choroidal vascularity and choriocapillaris blood perfusion in anisomyopic adults by SS-OCT/OCTA. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 62, 8 (2021).

Yang, J. et al. CVIS: Automated OCT-scan-based software application for the measurements of choroidal vascularity index and choroidal thickness. Acta Ophthalmol. (Copenh.) 100, e1553–e1560 (2022).

Yao, H. et al. Choroidal structural changes assessed with swept-source optical coherence tomography after cataract surgery in eyes with diabetic retinopathy. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 5839837 (2020).

Cicinelli, M. V. et al. Characterization of choriocapillaris and choroidal abnormalities in alport syndrome. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 11, 23 (2022).

Ledesma-Gil, G., Mao, Z., Liu, J. & Spaide, R. F. Denoising swept source optical coherence tomography volumetric scans using a deep learning model. Retina 42, 450–455 (2022).

Ma, J. P. et al. Longitudinal analysis of the retina and choroid in cognitively normal individuals at higher genetic risk of Alzheimer disease. Ophthalmol. Retina 6, 607–619 (2022).

Obada, O. et al. Choroidal assessment in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy by swept-source ocular coherence tomography and image binarization. Med. Kaunas 58, 918 (2022).

Robbins, C. B. et al. Choroidal structural analysis in Alzheimer disease, mild cognitive impairment, and cognitively healthy controls. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 223, 359–367 (2021).

Robbins, C. B. et al. Characterization of retinal microvascular and choroidal structural changes in Parkinson disease. JAMA Ophthalmol. 139, 182–188 (2021).

Velaga, S. B. et al. Choroidal vascularity index and choroidal thickness in eyes with reticular pseudodrusen. Retina 40, 612–617 (2020).

Su, L. et al. Evaluation of the choroid in women with uncomplicated pregnancy. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 9, 24 (2020).

Agrawal, R. et al. Choroidal vascularity index in central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina 36, 1646–1651 (2016).

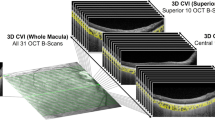

Cheong, K. X. et al. Three-dimensional modelling of the choroidal angioarchitecture in a multi-ethnic Asian population. Sci. Rep. 12, 3831 (2022).

Yip, V.C.-H. et al. A longitudinal study of choroidal changes following cataract surgery in patients with diabetes. Diab. Vasc. Dis. Res. 16, 369–377 (2019).

Chun, H. et al. Choroidal vascularity index change in macular telangiectasia type 2. PLoS ONE 17, e0262112 (2022).

Hwang, B. E. et al. Quantitative analysis of choroidal blood flow parameters in optical coherence tomography and angiography in central serous chorioretinopathy. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 260, 2111–2120 (2022).

Kim, M., Choi, S. Y. & Park, Y. H. Quantitative analysis of retinal and choroidal microvascular changes in patients with diabetes. Sci. Rep. 8, 12146 (2018).

Mirshahi, R. et al. Differentiating a pachychoroid and healthy choroid using an unsupervised machine learning approach. Sci. Rep. 12, 16323 (2022).

Yazdani, N. et al. Wide-field choroidal thickness and vascularity index in myopes and emmetropes. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 41, 1308–1319 (2021).

Azuma, K. et al. Assessment of the choroidal structure in pregnant women in the first trimester. Sci. Rep. 11, 4629 (2021).

Hanumunthadu, D. et al. Repeatability of swept-source optical coherence tomography retinal and choroidal thickness measurements in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 101, 603–608 (2017).

Asmussen, A., Smith, B. S., Møller, F. & Jakobsen, T. M. Repeatability and inter-observer variation of choroidal thickness measurements using swept-source optical coherence tomography in myopic Danish children aged 6–14 years. Acta Ophthalmol. (Copenh.) 100, 74–81 (2022).

Lau, J. K., Cheung, S. W., Collins, M. J. & Cho, P. Repeatability of choroidal thickness measurements with Spectralis OCT images. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 4, e000237 (2019).

Lal, B., Alonso-Caneiro, D., Read, S. A. & Carkeet, A. Repeatability of retinal and choroidal optical coherence tomography angiography indices in healthy children and young adults. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 44, 1114–1127 (2024).

Yamashita, T. et al. Repeatability and reproducibility of subfoveal choroidal thickness in normal eyes of Japanese using different SD-OCT devices. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 53, 1102–1107 (2012).

Mansoori, T., Charan, A. S. R., Suresh, N., Pesala, V. & Nagalla, B. Repeatability of choroidal thickness measurements in healthy subjects using RTVue XR optical coherence tomography. J. Curr. Ophthalmol. 34, 436–441 (2023).

Seddon, J. M. et al. Histopathological insights into choroidal vascular loss in clinically documented cases of age-related macular degeneration. JAMA Ophthalmol. 134, 1272–1280 (2016).

Lutty, G. A., McLeod, D. S., Bhutto, I. A., Edwards, M. M. & Seddon, J. M. Choriocapillaris dropout in early age-related macular degeneration. Exp. Eye Res. 192, 107939 (2020).

Sohrab, M., Wu, K. & Fawzi, A. A. A pilot study of morphometric analysis of choroidal vasculature in vivo, using EN face optical coherence tomography. PLoS ONE 7, e48631 (2012).

Borrelli, E. et al. In vivo mapping of the choriocapillaris in healthy eyes: A widefield swept-source OCT angiography study. Ophthalmol. Retina 3, 979–984 (2019).

Alagorie, A. R., Verma, A., Nassisi, M. & Sadda, S. R. Quantitative assessment of choriocapillaris flow deficits in eyes with advanced age-related macular degeneration versus healthy eyes. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 205, 132–139 (2019).

Trinh, M., Kalloniatis, M. & Nivison-Smith, L. Radial peripapillary capillary plexus sparing and underlying retinal vascular impairment in intermediate age-related macular degeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 62, 2 (2021).

Cheng, W. et al. Choriocapillaris flow deficits in normal Chinese imaged by swept-source optical coherence tomographic angiography. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 235, 143–153 (2022).

Chhablani, J. & Ruiz-Medrano, J. Choroidal Disorders (Academic Press, 2017).

Agrawal, R. et al. Choroidal vascularity index using swept-source and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography: A comparative study. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retina 50, e26–e32 (2019).

Espina, M. et al. Analysis of a confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope noncontact ultra-wide field lens system in retinal and choroidal disease. Retina Phila. Pa 35, 2664–2668 (2015).

Meshi, A. et al. Comparison of retinal pathology visualization in multi-spectral scanning laser imaging. Retina Phila. Pa 39, 1333–1342 (2019).

Barteselli, G., Bartsch, D.-U. & Freeman, W. R. Combined depth imaging using optical coherence tomography as a novel imaging technique to visualize vitreoretinal choroidal structures. Retina 33, 247–248 (2013).

Hashimoto, Y. et al. Changes in choroidal blood flow by diurnal variation in healthy young adults. Open Ophthalmol. J. 17, 1–6 (2023).

Han, R. et al. The choroid vascular index and its association with visual acuity in children and young adults with high myopia. Eye 37, 2542–2547 (2023).

Jing, R., Sun, X., Cheng, J., Li, X. & Wang, Z. Vascular changes of the choroid and their correlations with visual acuity in diabetic retinopathy. Front. Endocrinol. 15, 1327325 (2024).

Linsenmeier, R. A. & Padnick-Silver, L. Metabolic dependence of photoreceptors on the choroid in the normal and detached retina. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41, 3117–3123 (2000).

Longo, A., Geiser, M. & Riva, C. E. Subfoveal choroidal blood flow in response to light–dark exposure. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41, 2678–2683 (2000).

Tucker, W. D., Arora, Y. & Mahajan, K. Anatomy, Blood Vessels (StatPearls Publishing, 2023).

Rishi, P., Akhtar, Z., Agrawal, R., Agrawal, A. & Rishi, E. Analysis of choroidal structure and vascularity indices with image binarization of swept source optical coherence tomography images: A prospective study of 460 eyes. Oman J. Ophthalmol. 15, 49–55 (2022).

Liu, L. et al. Three-dimensional choroidal vascularity index in high myopia using swept-source optical coherence tomography. Curr. Eye Res. 47, 484–492 (2022).

Aksoy, M., Simsek, M. & Apaydın, M. Choroidal vascularity index in patients with type-1 diabetes mellitus without diabetic retinopathy. Curr. Eye Res. 46, 865–870 (2021).

Seo, W.-W., Yoo, H. S., Kim, Y. D., Park, S. P. & Kim, Y.-K. Choroidal vascularity index of patients with coronary artery disease. Sci. Rep. 12, 3036 (2022).

Verma, A. et al. Age-related alterations of the macular choroid in healthy eyes assessed by swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retina 54, 526–534 (2023).

Sadeghi, E. et al. Choroidal biomarkers in age-related macular degeneration. Surv. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2024.10.004 (2024).

Xie, J. et al. Choroidal thickness and its association with age, axial length, and refractive error in Chinese adults. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 63, 34–34 (2022).

Cai, W. et al. Two-year choroidal thickness attenuation and its associations in healthy Chinese adults. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 11, 21 (2022).

Lin, C. Y., Huang, Y. L., Hsia, W. P., Wang, Y. & Chang, C. J. Correlation of choroidal thickness with age in healthy subjects: Automatic detection and segmentation using a deep learning model. Int. Ophthalmol. 42, 3061–3070 (2022).

Ramrattan, R. S. et al. Morphometric analysis of Bruch’s membrane, the choriocapillaris, and the choroid in aging. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 35, 2857–2864 (1994).

May, C. A. Chronologic versus biologic aging of the human choroid. Sci. World J. 2013, 378206 (2013).

Chirco, K. R. et al. Monomeric C-reactive protein and inflammation in age-related macular degeneration. J. Pathol. 240, 173–183 (2016).

Vidal-Oliver, L., Spissinger, S., Herzig-de Almeida, E., Garzone, D. & Finger, R. P. Longitudinal changes in choroidal thickness and choroidal vascularity index in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Res. 67, 654–661 (2024).

Sonoda, S. et al. Choroidal structure in normal eyes and after photodynamic therapy determined by binarization of optical coherence tomographic images. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 55, 3893–3899 (2014).

Agrawal, R. et al. Choroidal vascularity index (CVI)-a novel optical coherence tomography parameter for monitoring patients with panuveitis?. PLoS ONE 11, e0146344 (2016).

Parthasarathy, M. K. & Bhende, M. Effect of ocular magnification on macular measurements made using spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 63, 427 (2015).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n71 (2021).

Page, M. J. et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n160 (2021).

Nivison-Smith, L., Kumar, M., Khuu, S. & Madigan, M. A systematic review and meta analysis of the choroidal vascularity Index (CVI) of the eye in individuals with no posterior eye disease?

Higgins, J. P. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0. 1. The Cochrane Collaboration. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org (2008).

Ga, W. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. In 3rd Symposium on Systematic Reviews: Beyond the Basics, Oxford, UK, 3–5 July 2000 (2000).

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. & Rothstein, H. R. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 1, 97–111 (2010).

Migliavaca, C. B. et al. Meta-analysis of prevalence: I 2 statistic and how to deal with heterogeneity. Res. Synth. Methods 13, 363–367 (2022).

Guyatt, G. et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 64, 383–394 (2011).

Schünemann, H., Brożek, J., Guyatt, G., Oxman, A. et al. The GRADE Handbook (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the University International Postgraduate Award and in part, by funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC #1174385). Professor Rupesh Agrawal (Singapore) is supported by grants awarded by the National Medical Research Council (NMRC), Ministry of Health, Republic of Singapore grant numbers: NRMC/CSAINV22jul-000, NMRC/CSAINV19nov-0007, and NMRC/CIRG21nov-0023. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, publication decisions, or manuscript preparation. We would also like to thank Nancy Briggs, Stats Central, Mark Wainwright Analytical Centre, UNSW Sydney, for their statistical expertise.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MK: Conceptualisation, methodology, statistical analysis, validation, investigation, data curation, writing. SKK : Methodology, statistical analysis, validation, investigation, writing, supervision. MT: Methodology, statistical analysis, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing, supervision. MCM: Methodology, statistical analysis, validation, formal analysis, writing, supervision. WRC: Formal analysis, validation, investigation, writing. RA: Formal analysis, validation, supervision, project administration, writing. LNS: Conceptualisation, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing, funding acquisition, supervision. All the authors have reviewed this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, M., Khuu, S.K., Trinh, M. et al. Choroidal vascularity index is independent of ocular and image-based factors in healthy eyes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 15, 27782 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10384-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10384-5