Abstract

Accurate modeling of multiple magnetic dipoles is essential for characterizing spacecraft-generated magnetic fields and mitigating their interference with sensitive onboard instruments. To address the limitations of conventional multiple magnetic dipole modeling (MDM) methods facing local convergence and the curse of dimensionality in complex magnetic source scenarios, this work proposes an adaptive hierarchical filtering particle swarm optimization (AHFPSO) algorithm. The algorithm incorporates a hierarchical filtering mechanism and an adaptive adjustment mechanism to improve its capability in solving MDM problems. Extensive simulations under both noise-free and noisy conditions demonstrate that AHFPSO consistently outperforms eight state-of-the-art PSO variants in terms of accuracy, robustness, success rate, and execution time, particularly in high-dimensional, multi-dipole scenarios. Experimental validation using standard magnets and a spacecraft transponder further confirms its practical applicability and high modeling precision. AHFPSO effectively identifies equivalent magnetic dipole moments that closely match the measured magnetic fields of the transponder, with average errors of -0.3472 nT, 0.7445 nT, and -0.4141 nT in the X, Y, and Z-axis directions, respectively. The proposed method enhances the capability of PSO to address complex, ill-posed MDM inverse problems and offers a promising tool for magnetic characterization in space missions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetic field measurement is one of the important tasks in deep space exploration, which allows for remote sensing of planetary magnetic fields, studying the magnetic structure and evolutionary history of planets, and providing insights into the spatial environment of celestial bodies in the solar system1,2,3. In deep space magnetic exploration missions, magnetic sensors are typically mounted on spacecraft composed of complex components, such as mechanical, electrical, and electronic systems. These components themselves can generate magnetic fields or contain magnetic materials, which may interfere with the magnetic detection data. To ensure the accuracy and reliability of magnetic measurements, it is necessary to restrict the spacecraft’s magnetic field4,5,6. This requires conducting a magnetic characterization of the spacecraft and implementing design modifications or compensation measures for components that cause significant magnetic interference7,8.

The multiple magnetic dipole modeling (MDM) method, originally proposed by Mehlem9, is a widely adopted approach for spacecraft magnetic characterization. This method involves decomposing each spacecraft subsystem into a set of equivalent magnetic dipoles, and subsequently integrating these models to estimate the overall magnetic field of the fully assembled spacecraft. Numerous space programs have benefited from this method with unit-level measurement techniques to meet increasingly stringent direct current requirements10,11. The unit-level measurement is typically carried out in dedicated facilities, namely the magnetic coil facility (MCF) and/or the multi-magnetometer facility (MMF)12, using the magnetic sensors like three-zxis fluxgate magnetometers to effectively capture the magnetic fields of equipment under test (EUT).

The MDM method has been proposed and refined in various forms over the past decades. With advances in mathematical techniques and optimization strategies, stochastic algorithms have increasingly replaced traditional deterministic methods for solving MDM problems, owing to their superior capability in handling complex and high-dimensional search spaces. Among these, particle swarm optimization (PSO) has emerged as one of the most widely used algorithms. Carrubba et al.13 were the first to apply PSO to MDM in space applications. Subsequently, Sheinker et al.14 proposed the use of the LASSO method for estimating the magnetic signature of ships. In addition, Spantideas et al.15 and Giannopoulos et al.16 introduced deep learning to solve the MDM problem. However, the limited interpretability of deep learning models and their reliance on large, labeled datasets pose significant challenges. Despite its simplicity, efficiency, and minimal parameter tuning requirements, PSO is prone to premature convergence and may become trapped in local optima. It worth nothing that extreme false solutions (with respect to the parameters of the magnetic moment and position) can occur when using PSO and/or any other optimization algorithms, especially in case of more than two magnetic dipole moments. Therefore, ongoing research should aim to enhance the robustness of optimization outcomes and reduce the uncertainties associated with parameter estimation.

Many variants of PSO have been proposed to find a global optimum solution. Since three important weighting factors (inertial weight, cognitive learning factor, and social learning factor) in PSO determine the learning process of the swarm, many research propose different settings of the factors based on stability analysis17. For instance, the most popular update rule of inertial weight is linear decreasing from 0.9 to 0.4 over the evolutionary process18, which is still applied in many PSO variants now. Motivated by the generation-based time-varying adjustments of inertial weight, Ratnaweera et al.19 further advocated a PSO with time-varying acceleration coefficients (HPSO-TVAC), where a larger cognitive learning factor and a smaller social learning factor are set at the initial evolutionary process and are gradually reversed during the search process. The Local Topology PSO (LPSO) proposed by Kennedy et al.20 suggests that a sparse neighbor topology is beneficial for complex multimodal problems, while a dense neighbor topology is more suitable for simpler unimodal problems. Besides, applying a hybridization strategy is a popular way to enhance the performance of PSO on complex problems. The genetic operators21,22 and some local searching strategies23,24 are popular auxiliaries to improve the population diversity and to speed up the convergence rate, respectively.

In addition to its application in spacecraft magnetic modeling, particle swarm optimization has been widely adopted in various geophysical and engineering domains. Essa et al.25 applied global PSO to interpret gravity anomalies caused by fault structures, demonstrating its effectiveness in hydrocarbon exploration and geological fault analysis. Essa26 further explored the use of PSO in self-potential anomaly interpretation, showcasing its utility in mineral exploration contexts. In power system engineering, Mehfuz and Kumar27 employed a two-dimensional PSO for load flow analysis, revealing its potential in electrical distribution optimization. Anderson et al.28 compared PSO-based inversion strategies for gravity anomalies and highlighted the importance of combining PSO with gradient filters to enhance robustness in noisy environments. Beyond geophysical inversion and power system engineering, PSO has demonstrated remarkable performance in solving various engineering optimization problems. It has been successfully applied to structural design optimization29,30, mechanical parameter tuning31, and even in construction scheduling32. These applications highlight the algorithm’s adaptability across diverse domains characterized by high-dimensional, nonlinear, and constrained optimization problems. These studies underscore the versatility and effectiveness of PSO in solving complex, ill-posed inverse problems across a range of scientific and engineering fields.

Inspired by the aforementioned research, a adaptive hierarchical filtering particle swarm optimization (AHFPSO) is proposed in this work to solve the MDM problem. The algorithm introduces two key mechanisms: hierarchical filtering and adaptive adjustment, aimed at improving the performance of PSO in optimizing multiple magnetic dipole moments. In the hierarchical filtering mechanism, the swarm is partitioned into multiple sub-swarms that evolve independently. The better-performing sub-swarms are promoted to subsequent layers for further refinement, while less effective ones are eliminated. Additionally, the adaptive adjustment mechanism monitors the evolution of each sub-swarm and dynamically adjusts their parameters to enhance its efficiency in exploring and exploiting the feasible solutions throughout the optimization process.

Mathematical formulation

Multi-magnetic dipoles modeling

According to the MMF, there are P magnetic sensors capturing the magnetic field generated by the EUT and the measured data can be expresssed as \(\varvec{B}_{m,p}\), where p denotes the \(p_{th}\) measurement point (\(p=1,2,\cdots ,P\)). The unit of \(\varvec{B}\) is tesla (T).

Given the parameters of M equivalent magnetic dipoles representing the magnetic characterization produced by a unit, the estimated parameters of these dipoles will be obtained by the optimization algorithm and the estimated magnetic field of each dipole is given by:

where \(\varvec{B}_{p,k}\) denotes the magnetic field vector generated by the \(k_{th}\) dipole (\(k=1,2,\cdots ,M\)) and captured at the \(p_{th}\) measurement point. In addition, \(\varvec{r}\) represents \(\varvec{r}_p-\varvec{r}_k\), i.e., the relative 3D position vector (in meters, m) from the k th dipole to the p th measurement point. \(\varvec{m}_k\) stands for the magnetic moment of the \(k_{th}\) dipole, with units of ampere square meters (A\(\cdot\)m2). \(\mu _0\) is the permeability of free space, with a value of \(4\pi \times 10^{-7}\) H/m. The total magnetic field at a measurement point can be calculated as the accumulated contribution of M dipoles, which can be expressed as

Equation (1) defines a forward problem in the sense that the magnetic field captured at the magnetic sensors is calculated based on the parameters of the magnetic dipole moments. In contrast, the inverse problem refers to the exploitation of the magnetic field measurements to identify the parameters of the magnetic dipole moments. This inverse problem is inherently ill-posed, particularly in cases involving multiple dipole sources. Small perturbations or noise in the magnetic field measurements may correspond to vastly different combinations of dipole moments and positions, leading to non-uniqueness and instability in the solution. This issue is exacerbated when the number of sensors is limited or the observation points are far from the sources, making it possible for multiple distinct configurations to generate nearly identical magnetic field patterns. Furthermore, if the number of dipoles assumed in the model does not match the actual number of sources, a feasible solution may not exist at all. To mitigate this ill-posedness, it is essential to ensure a sufficient number of well-distributed sensors and impose appropriate constraints on the solution space. Besides, for optimization algorithms, there should be a defined scalar fitness function c to evaluate the estimated error and guide the optimization in the next iteration.

where i represents the three dimension of x, y, z. To more precisely reflect small variations in the estimation error, all magnetic field values used in the fitness function are converted from tesla (T) to nanotesla (nT), where 1 T = 1\(\times 10^9\) nT. As a result, the unit of the fitness function value c is nanotesla (nT).

Canonical PSO

The particle swarm algorithm is a global optimization algorithm that originated from the study of bird predation33. The core idea of this algorithm is to use the sharing of information by individuals in the swarm to evolve from disorder to order in the problem solution space by the motion of the whole swarm, thus obtaining a feasible solution to the problem. Each particle has a certain position and velocity in the defined solution space. The position is a vector containing the parameters to be optimized. Since the magnetic moment and position of the dipole have a total of six parameters, the position of each particle is equal to the number of parameters of the dipole. The fitness function, defined as (3), is evaluated iteratively for each particle and compared with the best fitness locally (found by a single particle) and globally (found by the whole swarm). Afterwards, the positions and velocities of all particles are updated and the process is repeated until the algorithm converges to the best solution within a certain tolerance.

The procedure of the basic PSO can be summarized simply by two formulas

where \(\varvec{V}_i^t\) denotes the velocity of the ith particle at the tth iteration. \(\varvec{P}_{ibest}\) and \(\varvec{P}_{ibest}\) are the best individual position of the ith particle and the best position funded by the whole warm, respectively. \(r_1\) and \(r_2\) are two random functions equally distributed in the range (0,1). \(\omega\), \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) are three PSO weighting factors playing an important role in the convergence of the algorithm. In details, \(\omega\) is the inertial weight determining to what extent the particle remains along its original course. \(c_1\) is the cognitive learning factor, while \(c_2\) represents the social learning factor. A larger \(c_1\) makes the particle more likely to be influenced by its best previous position, while a larger \(c_2\) makes the particle more likely to be influenced by the global best position.

Adaptive hierarchical filtering particle swarm optimization algorithm

Carrubba et al. successfully applied PSO to inverse problems involving magnetic dipoles and demonstrated promising results for cases with one, two, or three magnetic moments. However, the success rate of the optimized solutions was not reported, and studies specifically addressing this aspect remain scarce. As the number of magnetic moments increases, the dimensionality of the solution space expands exponentially, greatly increasing the complexity of the problem and the probability of converging to suboptimal solutions. Consequently, enhancing the global optimization capability of PSO is of critical importance.

The overall framework of the proposed AHFPSO algorithm is depicted in Fig. 1. The left side of the figure illustrates the general workflow, while the right side highlights the two core components of the algorithm: the hierarchical filtering mechanism (HFM) and the adaptive adjustment mechanism (AAM). Here, Pbest denotes the best position previously found by an individual particle, and Gbest represents the best position identified by the entire swarm. The specific design and implementation details of AHFPSO are elaborated in the following subsections.

Setting sub-swarms by social learning factors

As discussed in the previous subsection, the parameters \(\omega\), \(c_1\), and \(c_2\) play a crucial role in determining the performance of PSO. In this work, \(\omega\) and \(c_1\) are kept constant, while \(c_2\) is adaptively varied. The proposed HFM focuses specifically on the influence of \(c_2\) by employing independent sub-swarms, each characterized by a distinct value of the social learning factor. Unlike previous studies that typically adjust learning factors as functions of time or iteration count, this work adopts a simpler yet more effective strategy. Fixed intervals are used to set a range of distinct \(c_2\) values, and the number of sub-swarms is determined accordingly. Each sub-swarm evolves independently under its assigned \(c_2\), thereby enabling diverse exploration and exploitation behaviors across the swarm population.

In this work, the maximum value of \(c_2\) is defined as the largest integer less than or equal to \(c_1\), denoted as \(c_{2,\text {max}} = \lfloor c_1 \rfloor\). The initial value of \(c_2\) is set to \(\delta\) (where \(\delta \in [0.05, 0.2]\) defines the step size), and subsequent \(c_2\) values are generated by incrementing in steps of \(\delta\). As a result, the total number of distinct \(c_2\) and hence the number of sub-swarms—is given by \(\lfloor c_{2,\text {max}} / \delta \rfloor + 1\).

Hierarchical filtering mechanism

While employing different social learning factors allows sub-swarms to exhibit diverse exploration behaviors during various phases of the search process, assigning a fixed number of iterations to each sub-swarm based solely on the number of \(c_2\) values may not sufficiently satisfy the exploration–exploitation balance required for the MDM problem. Uniformly allocating iterations can lead to inefficiencies. Some sub-swarms may spend excessive iterations on global exploration, thereby delaying the exploitation of promising or optimal solutions already found. Conversely, other sub-swarms may enter local exploitation too early without adequate exploration, increasing the risk of getting trapped in local optima. To address this issue, hierarchical filtering mechanism is proposed in this work, which allows for the independent configuration of the number of layers, the number of iterations per layer, and the number of sub-swarms within each layer. This mechanism enables adaptive filtering of sub-swarms based on their performance, ensuring that computational resources are dynamically allocated to favor those exhibiting superior convergence behavior. Through this layered strategy, HFM facilitates a more efficient and robust search process by progressively filtering and promoting the most promising sub-swarms for further evolution.

The number of layers and sub-swarms for each layer needs to be set based on the dimension of the problem. For the MDM problem, where each magnetic dipole moment consists of six parameters, setting 6M dimensions for the inversion of an EUT with M magnetic dipole moments is required. As the number of magnetic dipole moments increases, broader and deeper exploration is needed, hence, more sub-swarms need to be reserved. The HFM posits the following rules for designing the number of layers and sub-swarms for each layer:

The number of layers and sub-swarms within each layer are determined based on the dimensionality of the problem. In the case of MDM, each magnetic dipole moment is described by six parameters. Thus, for an EUT with M magnetic dipoles, the optimization problem has 6M dimensions. As the number of dipoles increases, a broader and deeper search of the solution space is required, necessitating a larger number of sub-swarms. To this end, HFM defines the following rules for designing the layer structure and sub-swarm distribution:

-

(1)

Initial Layer: The number of sub-swarms in the first layer corresponds to the number of predefined social learning factors.

-

(2)

Intermediate Layers: If the number of magnetic dipoles is fewer than five (\(D<5\)), three layers are configured. The number of sub-swarms in the second layer is set equal to the number of dipoles (D). If \(D \ge 5\), the number of sub-swarms in the second layer is initialized as \(\lfloor D/2 \rfloor\). This process continues recursively. If the resulting number of sub-swarms is still more than 5, it is again halved and used to define the next layer. This recursive halving continues until the number of sub-swarms falls below five. The resulting number then becomes the number of sub-swarms in the penultimate layer.

-

(3)

Final Layer: The number of sub-swarms is set to one, yielding a single final solution through deep exploitation of the most promising candidate.

To account for the varying exploration requirements and sub-swarm counts across layers, the number of iterations allocated to sub-swarms in each layer is adaptively adjusted according to the following formula:

where \(t_L^i\) denotes the number of iterations assigned to the \(i_{th}\) layer, and L is the total number of layers. MaxFEs represents the maximum allowable number of fitness function evaluations, and FEs refers to the current number of fitness function evaluations performed by the optimization algorithm. This allocation strategy ensures that global exploration stages receive sufficient iteration budgets to identify feasible solutions, while preserving computational resources for subsequent exploitation phases. More specifically, later layers, which are responsible for refining already promising solutions, are granted a greater share of the remaining computational budget, enabling deeper and more accurate local searches by elite sub-swarms.

The selection process between layers follows a straightforward filtering strategy. Upon completion of their assigned iterations, all sub-swarms within a layer are ranked based on their best fitness values in ascending order. The better-performing sub-swarms, in accordance with the pre-defined count for the next layer, are retained for further evolution, While the rest are discarded. This progressive filtering mechanism ensures that solution quality is continuously improved across layers, significantly reducing the risk of premature convergence to local optima, which is particularly important in high-dimensional and multi-extremum magnetic dipole modeling problems.

Adaptive adjustment mechanism

To overcome the limitations of PSO in trapping in local optima, various parameter adjustment and adaptive neighborhood search strategies have been proposed. These strategies typically adjust the inertia weight or other weighting factors in a linear or nonlinear manner, based on iterations or fitness values. These approaches advocate starting with local search modes and transitioning to global search modes. However, parameter adjustments based solely on iterations are not compatible with the methodology proposed in AHFPSO. Instead, the exploration or exploitation of each sub-swarm should be adaptive, depending on its specific optimization context, such as the need for local optimization or the need to escape local optima. When the fitness values of a sub-swarm stagnate, a transition from local to global search modes should occur to probe global optima. Once the fitness values begin to decrease, the sub-swarm can revert to local mode to explore new solutions while simultaneously exploiting known optimal solutions. This adaptive local strategy effectively addresses the challenge of multiple local optima, which is inherent in the MDM problem. In this work, the Adaptive Adjustment Mechanism is employed to dynamically modify both the neighborhood structure and the inertia weight in response to the optimization state of each sub-swarm.

Firstly, Eq. (4) can be modified using the formulas below

\(\varvec{P}_{nbest,i}\) is the best position of the neighbourhood surrounding the \(i_{th}\) particle. The neighbourhood size for each particle can be determined as

where \(N_S\) is the number of the particles in the swarm and the \(F_N\) is the minimum fraction of the neighbourhood. In each iteration, \(N_{size}\) particles are randomly selected as neighbors for each particle, and the best fitness value in the particle’s neighborhood are recorded as \(\varvec{P}_{nbest,i}\). When the fitness values of the sub-swarm stagnate, \(N_S\) should be enlarged, leading to a broader search range and escaping the local optima. Once the fitness values decrease, the neighbourhood size of each particle in the swarm should again decrease.

Besides, as local modes inherently lack local exploration capabilities, adjusting the inertia weight \(\omega\) in Eq. (7) is beneficial for local search when fitness values stagnate. A counter is used to track the number of consecutive iterations during which the fitness value of the sub-swarm does not improve. When the current global best fitness is worse than or equal to that of the previous iteration, the counter is incremented, indicating potential stagnation. Otherwise, the counter is decreased, reflecting ongoing progress. The inertia weight is then adaptively updated according to the value of this counter to promote either global or local search, using the following rule:

Here, \(\omega _{\max }=1.1\) and \(\omega _{\min }=0.1\) define the allowable range of the inertia weight to ensure stable swarm behavior. This adaptive mechanism allows the algorithm to increase \(\omega\) and refine local search when frequent improvement is observed, while reducing \(\omega\) to broaden the search scope when the optimization appears to have stagnated. In this way, the inertia weight serves as a feedback-driven controller for dynamic exploration and exploitation balancing during the optimization process.

Simulation of multiple magnetic dipoles modeling

Simulation setup

In this study, a cubic MMF with a side length of 0.320 m is employed. It is equipped with 18 three-axis fluxgate magnetometers mounted on its surfaces to measure the magnetic field surrounding the EUT, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Specifically, six magnetometers are installed on each of two opposite faces, while the remaining two faces each accommodate three magnetometers. The EUT is positioned at the center of the MMF. A simulation model of this setup is constructed to establish a virtual measurement environment for validating the performance of the proposed algorithm.

In the simulation, 18 magnetometers are arranged on the cubic MMF to measure the magnetic field surrounding the EUT. To thoroughly validate the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed algorithm, simulations were conducted with varying numbers of magnetic moments, ranging from one to five, representing different configurations of magnetic sources within a unit. To mitigate the influence of randomness, for each magnetic moment scenario, 1,000 independent optimization targets are randomly generated. Since this study focuses on magnetic modeling at the unit level for spacecraft components, the randomly generated magnetic moments and their spatial positions are constrained within realistic physical boundaries. Specifically, the size of the EUTs is limited to \(\pm 0.25m\times 0.25m\times 0.25m\), and the magnetic moments are bounded within \(\pm 0.5\)A\(\cdot\)m2.

To ensure fair competition, this study introduces eight competing PSO algorithms for comparative analysis. The reference parameters for these algorithms are provided in Table 1, in accordance with the guidelines specified in the relevant literature. All optimization algorithms in this work are executed with fixed random seeds to ensure full reproducibility and eliminate internal stochastic variability. For each optimization target, a single run is performed. Given the use of 1,000 distinct targets per configuration, the performance of the algorithm is assessed from a statistical perspective across a wide range of test cases. Each algorithm initializes with 60 particles. The MaxFEs is determined by the number of magnetic dipoles in the optimization target, calculated as \(6\times D \times 10000\), where D represents the number of magnetic dipole moments.

Although the mean value (Mean) and standard deviation (SD) of fitness values can be used as a metric to measure the performance of solution accuracy, it does not directly reflect the deviations between the optimized result and the target. Even with a small fitness value, the amplitude deviation of one dimension of the magnetic moment can be large. Therefore, this study incorporates the success rate (SR) as a metric to evaluate the performance of the algorithms.

The deviations in magnitudes (\(\Delta \varvec{m}\)) and positions (\(\Delta \varvec{d}\)) between the optimized and the true magnetic dipole moment are defined as follows:

where i represents the three dimension of x, y, z. \(\varvec{m}_{k,i}^{opt}\) and \(\varvec{r}_{k,i}^{opt}\) represent the optimized results and \(\varvec{m}_{k,i}\) and \(\varvec{r}_{k,i}\) are the ground truth.

For each set of magnetic moments, every algorithm has a recorder \(t_{SR}\) recording the number of successful outcomes:

When the deviation between the position of the optimized and the true magnetic dipole moment is smaller than \(\varvec{\epsilon _1}\), or the deviation in the magnitude of the magnetic dipole moment is smaller than \(\varvec{\epsilon _2}\), the optimization is considered successful; otherwise, it is considered a failure. In this study, the maximum deviation between the position and magnitude of the optimized and the target is set to 0.001 \(A\cdot m^2\) and 0.01 m, respectively.

Thus the success rate (SR) of each algorithm can be defined as follows:

where \(N_t\) is the number of the optimization targets.

To further assess the computational efficiency of each algorithm, we also record the average wall-clock execution time of all methods under the same simulation conditions. All experiments are conducted on a machine equipped with an Intel i7-13700 CPU and 16 GB RAM, and the algorithms are implemented in MATLAB. The execution time is measured from the start of each algorithm until convergence or reaching the maximum number of fitness evaluations.

Simulation results and analysis

Two sets of simulations conducted on nine particle swarm optimization algorithms are presented in this section. One without measurement noise and the other with noise included. To comprehensively evaluate the performance of each algorithm, the results are analyzed based on the mean, SD, and SR of the optimization outcomes. Furthermore, the Friedman test is applied to perform a statistical comparison, enabling the assessment of the relative strengths and weaknesses of the algorithms. The average ranking (AR) is calculated for each algorithm based on its performance in terms of mean, SD, and SR. The final ranking (FR) is then determined by averaging the AR values across these three indicators.

Simulation results and analysis without noise

The optimization results under noiseless conditions are presented in Table 2. When the number of magnetic dipole moments equals 1, MAPSO performs the best, followed by AHFPSO, which succeeds in inverting one fewer magnetic dipole moment than MAPSO. As the number of moments increases, AHFPSO consistently performs the best, with the standard deviation slightly higher than MAPSO only when optimizing three moments. When the number of magnetic moments equals 3, AHFPSO is the only algorithm with a success rate exceeding 90%, while MAPSO’s success rate is only 81.40%. When the number of magnetic moments increases to five, the inversion problem becomes significantly more challenging due to the higher dimensionality and the increased presence of local optima. In this case, only TAPSO, MAPSO, and AHFPSO achieve success rates above 20%. Notably, AHFPSO reaches a success rate of 52.10%, exceeding the second-best result by 20.30%. These results demonstrate that the proposed AHFPSO effectively improves the performance of particle swarm optimization in solving the MDM problem.

Moreover, the proposed AHFPSO enhances the PSO algorithm through the integration of the HFM and the AAM. These components are more sophisticated and provide greater performance improvements compared to variants such as MPSO and AWPSO. Although these enhancements result in increased computational demands, they contribute significantly to the algorithm’s overall effectiveness. For instance, the average execution time required by AHFPSO to optimize five magnetic dipole moments is 148.71 seconds. While this duration is longer than that of MPSO, AWPSO, and PPSO, AHFPSO achieves a substantially higher success rate than these three algorithms. In contrast, algorithms that exhibit higher execution times than AHFPSO tend to deliver lower success rates. This performance disparity is attributed to the HFM, which enables AHFPSO to efficiently identify suitable social learning factors tailored to the optimization target, and the AAM, which helps sub-swarms escape from local optima. Notably, the computational time of AHFPSO remains well within acceptable limits, particularly considering that magnetic dipole optimization for spacecraft is typically performed during ground-based testing, where real-time constraints are less critical.

To further assess the overall performance of the algorithms, the Friedman test is conducted. As shown in Table 2, AHFPSO achieves the highest rankings in both ARs and FR, excluding the AR associated with execution time. This indicates that AHFPSO demonstrates the most consistent and effective performance among the evaluated algorithms. The rankings of the other state-of-the-art PSO variants are comparatively close, reflecting a competitive performance landscape.

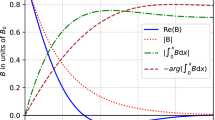

The convergence curves of the competing algorithms for varying numbers of magnetic dipole moments are illustrated in Fig. 3, specifically D=1, D=3, and D=5. For each scenario, four representative samples are selected to demonstrate the optimization behavior. In the case of D=1, where the number of magnetic dipole moments is minimal and the parameter space is of low dimensionality (only six dimensions), most algorithms exhibit satisfactory performance. However, in sample 1, several algorithms including XPSO, AWPSO, MPSO, EOPSO, and PPSO converge to local optima, resulting in suboptimal solutions consistent with the results reported in Table 2. As the number of magnetic dipole moments increases, the dimensionality of the parameter space also increases, leading to a more complex optimization landscape. When D=3, AHFPSO demonstrates the best performance in samples 1, 2, and 4. Although TAPSO outperforms AHFPSO in sample 3, AHFPSO still achieves higher optimization accuracy than the other competing algorithms. When the number of dipole moments increases to D=5, most algorithms tend to fall into local optima, particularly in samples 2, 3, and 4. Although TAPSO achieves better results than AHFPSO in samples 1 and 4, AHFPSO consistently maintains high accuracy across all samples, indicating its robustness in high-dimensional and complex scenarios.

It is noteworthy that Fig. 3j and 3k also clearly illustrate the process of hierarchical filtering. Initially, AHFPSO constructs a corresponding number of sub-swarms based on the quantity of social learning factors. When the FEs reach \(0.3 \times 10^6\), five sub-swarms are selected for further optimization. When the FEs is between \(0.3 \times 10^6\) and \(0.9 \times 10^6\), five distinct peaks appear in the convergence curves, reflecting the continued evolution of the five sub-swarms based on the results from the first layer. Subsequently, when the FEs reach \(0.9 \times 10^6\), two sub-swarms with superior performance are selected to continue independent iterations. When FEs equal \(1.8 \times 10^6\), the best-performing sub-swarm is retained to proceed with further iterations until the maximum number of evaluations is reached, after which the final results are output.

Convergence curves of different algorithms on fitness function with different optimization targets. (a), (b), (c), (d) and (e), (f), (f), (g) and (i), (j), (k), (l) are optimization dynamics for different algorithms on fitness function with different parameter sets at \(D=1\), \(D=3\) and \(D=5\), respectively.

Simulation results and analysis with noise

It is important to note that the calculated magnetic field represents the theoretical magnetic field. Even when the EUT and the MMF are placed in a zero magnetic field environment, it is difficult to avoid the influence of magnetometers baseline noise or environmental magnetic field fluctuations. To account for these effects, Gaussian noise is added to the simulated magnetic field data to simulate the noise that may exist in the measurement process. The added noise has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 15 nT. This variance is chosen based on typical magnetic field fluctuations in normal conditions, which are generally less than 15 nT. Additionally, the maximum deviation between the position and magnetic moment of the optimized and the target is set to 0.005 A\(\cdot\)m2.

The optimization results under noisy conditions are summarized in Table 3. AHFPSO demonstrates superior stability and accuracy across different tested dipole configurations compared to the other algorithms. When the number of magnetic dipole moments is small (i.e., one or two), MAPSO performs relatively better due to its multiple adaptation strategies, with AHFPSO closely following. However, when the number of magnetic dipoles is two, AHFPSO achieves a success rate that is 1.60% higher than that of MAPSO. In the case of three dipoles (D=3), AHFPSO maintains a success rate of 75.30% under noisy conditions, which is notably higher than those of MAPSO (71.80%) and TAPSO (59.10%). The other algorithms exhibit success rates below 50%. Even in the most challenging scenario, with five magnetic sources (D=5), AHFPSO still achieves a success rate of 24.80%, which is approximately two to five times higher than those of the other algorithms.

A Friedman test is also conducted on the optimization results obtained under noisy conditions. AHFPSO ranks first in terms of mean, SD, and SR, indicating that it maintains both accuracy and stability in the presence of noise. Although MAPSO, which ranks second overall, achieves the same average ranking as AHFPSO for SD, its average ranking for SR is noticeably lower. In terms of execution time, AHFPSO attains an average ranking of 3.20, which is lower than that of most state-of-the-art (SOTA) PSO variants.

In addition, this work compares the performance of AHFPSO under both noisy and noise-free conditions. After introducing Gaussian noise with a standard deviation of 15 nT, a decrease in overall performance is observed. However, AHFPSO consistently maintains the top ranking across all test scenarios, demonstrating strong robustness against measurement noise. When D=1 or D=2, the success rate of AHFPSO declines only slightly, remaining above 90%. As the number of magnetic dipole moments increases, the success rate declines more noticeably. In particular, for five dipole moments, it drops from 52.10% to 24.80%. This suggests that the impact of noise becomes more pronounced in higher-dimensional solution spaces, likely due to an increased number of local optima that hinder the convergence of the optimization process.

Despite this decline, AHFPSO continues to outperform other SOTA PSO variants under noisy conditions. This confirms that the HFM and AAM incorporated in AHFPSO effectively support the algorithm in escaping local optima. These mechanisms selectively filter out underperforming sub-swarms and dynamically adjust individual neighborhoods and inertia weights based on the evolutionary state of each sub-swarm, thereby maintaining a balance between global exploration and local exploitation.

Ablation study

To evaluate the performance of the hierarchical filtering mechanism and adaptive adjustment mechanism proposed in this work, ablation study is conducted. The particle swarm optimization with the hierarchical filtering mechanism is denoted as HFPSO, and the particle swarm optimization with the adaptive adjustment mechanism is denoted as APSO. The optimization results of PSO, HFPSO, APSO, and AHFPSO under noise-free conditions are presented in Table 4.

The simulation results are significantly clear. For all performance metrics, the algorithms rank from highest to lowest as AHFPSO, APSO, HFPSO, and PSO. Compared to the standard PSO, the particle swarm with the hierarchical filtering mechanism (HFPSO) shows improvements in optimization results, including the mean, standard deviation, and success rate, indicating that the hierarchical filtering mechanism can selectively filter and choose parameters that are suitable for the current inversion objective, thus enabling further iterative optimization. This not only saves computational resources but also improves the success rate of the inversion. APSO, on the other hand, exhibits even better performance, especially in terms of the inversion success rate, which shows a noticeable improvement over HFPSO. This suggests that the adaptive adjustment mechanism can dynamically adjust the inertia weight based on the current sub-group’s inversion status, effectively improving the balance between exploration and exploitation, and avoiding the algorithm from getting trapped in local optima. Although APSO achieves a higher success rate at lower problem dimensions, AHFPSO, which combines both the hierarchical filtering mechanism and adaptive adjustment mechanism, demonstrates the best performance. Its higher average success rate ranking indicates robust inversion performance across different objectives.

It clearly shows that the algorithms rank from highest to lowest as AHFPSO, APSO, HFPSO, and PSO for all performance metrics expect for the execution time. Compared to the PSO, the PSO with the HFM (HFPSO) shows improvements in optimization results, including the mean, standard deviation, and success rate, indicating that the ability of HFM to handle the competition, filtering, and elimination between sub-swarms. It selects appropriate learning factor combinations for the current optimization target. This not only saves computational resources but also improves the success rate of the inversion. APSO, on the other hand, exhibits even better performance, especially in terms of the success rate, which shows a noticeable improvement over HFPSO. This suggests that the AAM focuses on self-adjusting the parameters within the sub-swarm during the optimization process. When a sub-swarm is trapped in a local optimum or the iteration stagnates, the AAM adjusts the inertia weight to help the individuals within the sub-swarm escape from local optima. Although APSO achieves a higher success rate at lower problem dimensions, AHFPSO, which combines both the HFM and AAM, shows the best performance. Its higher average success rate ranking indicates robust inversion performance across different objectives. Regarding the average execution time, APSO, HFPSO, and AHFPSO all show higher average execution times than PSO, but they remain within acceptable limits.

Convergence curves of PSO, APSO, HFPSO and AHFPSO on fitness function with different optimization targets. (a), (b), (c), (d) and (e), (f), (f), (g) and (i), (j), (k), (l) are optimization dynamics for different algorithms on fitness function with different parameter sets at \(D=1\), \(D=3\) and \(D=5\), respectively.

The convergence curves for PSO, APSO, HFPSO, and AHFPSO on the MDM problem with varying numbers of magnetic dipole moments (D=1, D=3, and D=5) are shown in Fig. 4, with four samples displayed for each case. When the problem dimension is low (D=1), the solution space is smaller. Thanks to the adaptive adjustment mechanism, APSO converges the fastest. In contrast, AHFPSO and HFPSO require a few more iterations to complete the sub-swarm filtering and gradually converge, due to the HFM. As the dimensionality increases, the solution space expands, and more local minima emerge. The advantage of the HFM becomes more apparent. In Fig. 4j, although APSO can adaptively adjust individual neighborhoods and the inertia weight, it is still unable to escape local minima due to the fixed social learning factor (\(c_2\)=1.5). On the other hand, AHFPSO, which incorporates the HFM, eliminates the sub-swarm with a social learning factor of 1.5 after the first layer, indicating that this learning factor is not suitable for the current optimization target. Besides, with the adaptive adjustment mechanism, AHFPSO helps sub-swarms with different social learning factors escape local minima more efficiently, accelerating the convergence speed of the sub-swarms.

Experimental validation with standard magnets and a transponder

Experimental setup

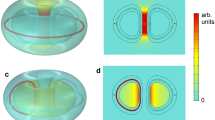

In the experimental validation, a spherical MMF is employed to measure the magnetic field, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The device is composed of six semicircular aluminum alloy rings, each spaced 60 degrees apart. Three sliding modules are installed on each ring, and each module is capable of holding a magnetic sensor to detect the magnetic field generated by the object placed at the center of the MMF. The three modules on each ring are evenly distributed with an angular separation of 45 degrees, resulting in a total of 18 magnetic sensors. All sensors are positioned 12 cm from the center of the device.

The magnetic sensors used in the setup are CH-688FLL three-axis fluxgate magnetometers. The main technical specifications of the magnetometers are provided in Table 5. To minimize external interference, the MMF is placed within a near-zero magnetic field environment. To evaluate the practical applicability of the proposed algorithm, both standard magnets and a transponder are used as test objects. These objects are positioned at the center of the MMF, and magnetic field data are collected under noise-free environmental conditions. The acquired data are subsequently processed using the proposed AHFPSO algorithm for modeling multiple magnetic dipole moments.

Magnetic dipole moment modeling for standard magnets

Three standard magnets are employed as the test object in the experiment to validate the performance of the proposed AHFPSO algorithm. Each magnet possesses a magnetic dipole moment of 0.5 A\(\cdot\)m2. The magnets are placed inside the MMF, as illustrated in Fig. 5, with an enlarged view provided to emphasize their spatial arrangement. The corresponding magnetic moments and spatial coordinates of the magnets are detailed in Table 6.

For the three standard magnets, the magnetic moment is constrained to the range of ±1 A\(\cdot\)m2 as the bounds for AHFPSO, while the boundary of the position is set to ±0.2 m. Given that there are three magnetic sources, MaxFEs is set to \(1.8 \times 10^6\). The optimized results obtained by AHFPSO are listed in Table 7.

A comparison between the data in Table 6 and Table 7 indicates that AHFPSO yields highly accurate results when applied to estimate the positions and magnetic moments of the three standard magnets. The maximum position error is 0.0036 m, and the maximum magnetic moment error is 0.0044 A\(\cdot\)m2. These small errors demonstrate that AHFPSO effectively and accurately reconstructs the physical parameters of the magnetic sources.

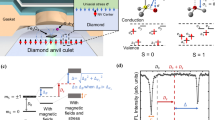

Multiple magnetic dipole moments modeling of a transponder

This subsection addresses the modeling of multiple magnetic dipole moments within a transponder, a device commonly used in spacecraft. The transponder is primarily designed to receive signals from ground stations, amplify and frequency-shift them, and subsequently retransmit the processed signals back to Earth. Due to the presence of multiple minor magnetic sources within the transponder, ground-based modeling of its magnetic dipole moments is essential for accurately characterizing its magnetic properties. The spherical MMF is used to measure the magnetic field generated by the transponder, as illustrated in Fig. 6.

Since the number of magnetic sources within the transponder is unknown, an assumption regarding the number of dipoles is necessary. In this experiment, it is assumed that the transponder contains between one and five magnetic sources. The corresponding fitness values for these assumptions are 878 nT, 247 nT, 252 nT, 87 nT, and 147 nT, respectively. Based on the lowest fitness value, the configuration with four equivalent magnetic dipole moments is selected. The corresponding parameters optimized by AHFPSO are provided in Table 8.

The convergence curve of AHFPSO during the transponder modeling process is presented in Fig. 7, clearly illustrating the hierarchical filtering and convergence progression. According to the procedure described in Section 3, the optimization process is structured into four layers when modeling four magnetic dipole moments. Initially, AHFPSO utilizes 15 distinct social learning factors to guide 15 sub-swarms independently. When the FEs reaches \(2.4\times 10^5\), the algorithm selects the four best-performing sub-swarms, namely sub-swarms 2, 4, 5, and 9, to advance to the second layer, while the remaining sub-swarms are eliminated. In the second layer, sub-swarms 2 and 9 outperform the others and proceed to the third layer. The fitness values reveal that sub-swarm 9 performs better than sub-swarm 2, leading to its advancement to the fourth and final layer. Ultimately, sub-swarm 9 identifies the four equivalent magnetic dipole moments of the transponder.

To verify whether the four optimized equivalent magnetic dipole moments accurately represent the transponder’s magnetic characteristics, the distance between each magnetometer and the center of the device is set to 17 cm for field measurements. The magnetic fields generated by the optimized dipole moments are then computed and compared with the experimentally measured magnetic fields to assess the accuracy of the optimization results. The errors between the calculated and measured magnetic fields at all 18 magnetometer positions are presented in Fig. 8.

The maximum error is observed at magnetometer number 9 along the X-axis, with a value of -4.9035 nT. The average errors in the X, Y, and Z directions are -0.3472 nT, 0.7445 nT, and -0.4141 nT, respectively. These results indicate that the magnetic fields reconstructed from the optimized dipole parameters closely match the measured values. Therefore, the four equivalent magnetic dipole moments identified using AHFPSO provide an accurate characterization of the transponder’s magnetic properties.

Furthermore, the multiple magnetic dipole moments of the transponder can be incorporated into the overall magnetic model of the spacecraft, alongside those of other onboard components. This system-level integration enables a comprehensive characterization of the spacecraft’s magnetic environment, ensuring that the resulting magnetic fields in designated operational zones or magnetically sensitive areas remain within the predefined design thresholds.

Discussion

The hierarchical filtering mechanism proposed in this work primarily handles the selection and elimination between multiple swarms. Its main function is to eliminate underperforming subgroups layer by layer to allocate more computational resources to the subgroups guided by this factor and identify the appropriate social learning factor for solving the current objective. However, HFM does not directly participate in the velocity and position updates within each sub-swarm. This simple and independent mechanism, which is solely dependent on the social learning factor, allows for easy integration with other SOTA PSO variants. In other words, the optimization strategies used by other advanced PSO algorithms can be easily combined with HFM, replacing the adaptive adjustment mechanism proposed in this sork. Therefore, this work integrates HFM with three advanced PSO variants (ADFPSO, TAPSO, and MPSO). The optimization results before and after the combination of the HFM without noise are shown in Table 9.

It is evident from the table that, for both ADFPSO and TAPSO, the addition of the HFM leads to improvements in terms of Mean, SD, and SR, compared to the original algorithms. This validates the effectiveness of the HFM proposed in this work. Notably, the success rate of HFTAPSO in the inversion of five magnetic dipoles reached 52.7%, surpassing the AHFPSO proposed in this work. The possible reason is that the strategies proposed within TAPSO are more effective than the AAM, which indirectly confirms the enhancement brought by HFM to the variants of PSO. For MPSO, it outperforms HFMPSO when D=1. This could be attributed to the relatively MaxFEs set in this case, which may cause additional computational costs during the selection process of the HFM. As a result, the sub-swarms filtered by HFM do not have sufficient iterations to complete convergence, leading to poorer optimization results compared to MPSO. However, as the number of dipoles increases, the results of HFMPSO consistently outperform MPSO.

The results in Table 9 provide strong evidence that the proposed HFM enhances the performance of other PSO variants on the MDM problem. However, the HFM also has its limitations. Since it relies on the social learning factor to define different sub-swarms, with each sub-swarm corresponding to a unique social learning factor, HFM is unable to integrate with algorithms that modify or replace the social learning factor, such as AWPSO, MAPSO, and others.

Moreover, although the AHFPSO proposed in this work has demonstrated its ability to effectively improve the optimization performance on the MDM problem, its application complexity still faces certain limitations. Future work will focus on extending the current approach to explore its application to more complex magnetic sources, such as magnetic quadrupoles or higher-order moments. Two magnetic dipoles require twelve parameters, while a magnetic quadrupole only requires eight parameters, which reduces the number of parameters that need to be optimized. This may simplify the optimization process and improve computational efficiency. This direction not only has the potential to further enhance algorithm efficiency but also provides a broader solution for magnetic source inversion problems. Additionally, incorporating more complex source terms, such as magnetic quadrupoles and higher-order moments, may present new challenges, such as optimizing higher-dimensional parameter spaces. We plan to further investigate this direction in future research to enhance the adaptability and versatility of the proposed method.

Conclusion

In this work, an adaptive hierarchical filtering particle swarm optimization algorithm is proposed to address the challenges of multiple magnetic dipole modeling in complex spacecraft systems. The inverse MDM problem is inherently ill-posed and susceptible to noise, local optima, and high dimensionality. To overcome these issues, AHFPSO integrates two key mechanisms: a Hierarchical Filtering Mechanism (HFM) that promotes high-performing sub-swarms across multiple layers based on their social learning factors, and an Adaptive Adjustment Mechanism (AAM) that dynamically modifies the neighborhood size and inertia weight based on the optimization status of each sub-swarm.

Comprehensive simulations under both noise-free and noisy conditions demonstrate that AHFPSO consistently outperforms eight SOTA PSO variants in terms of accuracy, robustness, success rate, and computational efficiency. Notably, it achieves success rates of 52.10% and 24.80% in the most challenging five-dipole scenario under noise-free and noisy conditions, respectively—significantly higher than those of the competing algorithms. An ablation study further confirms that both HFM and AAM substantially contribute to the overall performance, with their combination yielding the most robust and stable results. Experimental validations using standard magnets and a transponder show that AHFPSO can accurately reconstruct real magnetic dipole configurations. For the transponder, the optimized four-dipole configuration yields an average magnetic field error below 1 nT, verifying the method’s high modeling precision. Moreover, the HFM is designed to be modular and independent from the internal dynamics of sub-swarms, allowing seamless integration with other advanced PSO variants. Discussion and further simulation show that coupling HFM with variants such as ADFPSO, TAPSO, and MPSO significantly improves their success rates without incurring excessive computational costs.

Based on the structure and layout of each piece of equipment on the spacecraft, the magnetic model of the equipment precisely characterized by AHFPSO can be integrated into the spacecraft’s overall magnetic model. This model not only allows for the calculation of the magnetic field in any internal or external zone of the spacecraft, enabling the verification of magnetic field-related indicators, but also allows for design modifications and/or compensation to be applied to spacecraft components that exhibit significant magnetic interference.

In summary, AHFPSO provides a powerful and adaptable framework for solving ill-posed inverse problems in magnetic dipole modeling. Its strong performance under noiseless and noisy condition and problem complexities makes it a promising tool for spacecraft equipment magnetic characterization, enabling the integration of unit-level magnetic models into system-level spacecraft analysis to ensure compliance with stringent magnetic cleanliness requirements.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Du, A. et al. The chinese mars rover fluxgate magnetometers. Space Sci. Rev. 216, 1–15 (2020).

Connerney, J. et al. The maven magnetic field investigation. Space Sci. Rev. 195, 257–291 (2015).

Connerney, J. et al. The juno magnetic field investigation. Space Sci. Rev. 213, 39–138 (2017).

Fragiadakis, N., Baklezos, A. T., Kapetanakis, T. N., Vardiambasis, I. O. & Nikolopoulos, C. D. A cooperative method based on joint electric and magnetic cleanliness for space platforms emc assessments. IEEE Access 10, 130850–130860 (2022).

Chen, X., Liu, S., Sheng, T., Zhao, Y. & Yao, W. The satellite layout optimization design approach for minimizing the residual magnetic flux density of micro-and nano-satellites. Acta Astronautica 163, 299–306 (2019).

Hoffmann, A. P., Moldwin, M. B., Strabel, B. P. & Ojeda, L. V. Enabling boomless cubesat magnetic field measurements with the quad-mag magnetometer and an improved underdetermined blind source separation algorithm. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 128, e2023JA031662 (2023).

Kuznetsov, B. et al. Method for control by orbital spacecraft magnetic cleanliness based on multiple magnetic dipole models with consideration of their uncertainty. Electr. Eng. & Electromechanics 47–56 (2023).

Pous, M. et al. Time-domain electromagnetic characterization of reaction wheel for space applications. IEEE Trans. Electromagn Compat. 65, 365–375 (2023).

Mehlem, K. Multiple magnetic dipole modeling and field prediction of satellites. IEEE Trans. Magn. 14, 1064–1071 (1978).

Pudney, M. et al. Solar orbiter strategies for emc control and verification. In 2019 ESA Workshop on Aerospace EMC (Aerospace EMC), 1–6 (IEEE, 2019).

Kaiser, M. L. et al. The stereo mission: An introduction. Space Sci. Rev. 136, 5–16 (2008).

Tsatalas, S. et al. A novel multi-magnetometer facility for on-ground characterization of spacecraft equipment. Measurement 146, 948–960 (2019).

Carrubba, E., Junge, A., Marliani, F. & Monorchio, A. Particle swarm optimization to solve multiple dipole modelling problems in space applications. In 2012 ESA Workshop on Aerospace EMC, 1–6 (IEEE, 2012).

Sheinker, A., Ginzburg, B., Salomonski, N., Yaniv, A. & Persky, E. Estimation of ship’s magnetic signature using multi-dipole modeling method. IEEE Trans. Magn. 57, 1–8 (2021).

Spantideas, S. T., Giannopoulos, A. E., Kapsalis, N. C. & Capsalis, C. N. A deep learning method for modeling the magnetic signature of spacecraft equipment using multiple magnetic dipoles. IEEE Magn. Lett. 12, 1–5 (2021).

Giannopoulos, A. E., Spantideas, S. T., Nikolopoulos, C. D., Baklezos, A. T. & Capsalis, C. N. Dipole fitting in unit-level spacecraft equipment with deep neural networks. In 2022 ESA Workshop on Aerospace EMC (Aerospace EMC), 1–5 (IEEE, 2022).

Samal, N. R., Konar, A., Das, S. & Abraham, A. A closed loop stability analysis and parameter selection of the particle swarm optimization dynamics for faster convergence. In 2007 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, 1769–1776 (IEEE, 2007).

Shi, Y. & Eberhart, R. A modified particle swarm optimizer. In 1998 IEEE international conference on evolutionary computation proceedings. IEEE world congress on computational intelligence (Cat. No. 98TH8360), 69–73 (IEEE, 1998).

Ratnaweera, A., Halgamuge, S. K. & Watson, H. C. Self-organizing hierarchical particle swarm optimizer with time-varying acceleration coefficients. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 8, 240–255 (2004).

Kennedy, J. & Mendes, R. Population structure and particle swarm performance. In Proceedings of the 2002 Congress on Evolutionary Computation. CEC’02 (Cat. No. 02TH8600), vol. 2, 1671–1676 (IEEE, 2002).

Angeline, P. J. Using selection to improve particle swarm optimization. In 1998 IEEE International Conference on Evolutionary Computation Proceedings. IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence (Cat. No. 98TH8360), 84–89 (IEEE, 1998).

Xia, X. et al. Triple archives particle swarm optimization. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 50, 4862–4875 (2020).

Qu, B.-Y., Liang, J. J. & Suganthan, P. N. Niching particle swarm optimization with local search for multi-modal optimization. Inf. Sci. 197, 131–143 (2012).

Xia, X., Liu, J. & Hu, Z. An improved particle swarm optimizer based on tabu detecting and local learning strategy in a shrunk search space. Appl. Soft Comput. 23, 76–90 (2014).

Essa, K. S., Géraud, Y. & Diraison, M. Fault parameters assessment from the gravity data profiles applying the global particle swarm optimization. J. Petroleum Sci. Eng. 207, 109129 (2021).

Essa, K. S. A particle swarm optimization method for interpreting self-potential anomalies. J. Geophys. Eng. 16, 463–477 (2019).

Mehfuz, S. & Kumar, S. Two dimensional particle swarm optimization algorithm for load flow analysis. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 7, 1074–1082 (2014).

Anderson, N. L., Essa, K. S. & Elhussein, M. A comparison study using particle swarm optimization inversion algorithm for gravity anomaly interpretation due to a 2d vertical fault structure. J. Appl. Geophys. 179, 104120 (2020).

Zakian, P. & Kaveh, A. Seismic design optimization of engineering structures: a comprehensive review. Acta Mech. 234, 1305–1330 (2023).

Minh, H.-L., Khatir, S., Rao, R. V., Abdel Wahab, M. & Cuong-Le, T. A variable velocity strategy particle swarm optimization algorithm (vvs-pso) for damage assessment in structures. Eng. with Comput. 39, 1055–1084 (2023).

Rugveth, V. S. & Khatter, K. Sensitivity analysis on gaussian quantum-behaved particle swarm optimization control parameters. Soft Comput. 27, 8759–8774 (2023).

Shehadeh, A., Alshboul, O., Al-Shboul, K. F. & Tatari, O. An expert system for highway construction: Multi-objective optimization using enhanced particle swarm for optimal equipment management. Expert. Syst. with Appl. 249, 123621 (2024).

Kennedy, J. & Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of ICNN’95-international conference on neural networks, vol. 4, 1942–1948 (IEEE, 1995).

Xia, X. et al. An expanded particle swarm optimization based on multi-exemplar and forgetting ability. Inf. Sci. 508, 105–120 (2020).

Liu, W. et al. A novel sigmoid-function-based adaptive weighted particle swarm optimizer. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 51, 1085–1093 (2019).

Wei, B. et al. Multiple adaptive strategies based particle swarm optimization algorithm. Swarm Evol. Comput. 57, 100731 (2020).

Liu, H., Zhang, X.-W. & Tu, L.-P. A modified particle swarm optimization using adaptive strategy. Expert Syst. Appl. 152, 113353 (2020).

Yu, F., Tong, L. & Xia, X. Adjustable driving force based particle swarm optimization algorithm. Inf. Sci. 609, 60–78 (2022).

Zhao, S. & Wang, D. Elite-ordinary synergistic particle swarm optimization. Inf. Sci. 609, 1567–1587 (2022).

Li, T., Shi, J., Deng, W. & Hu, Z. Pyramid particle swarm optimization with novel strategies of competition and cooperation. Appl. Soft Comput. 121, 108731 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Key Research and Development Program of China under Grant 2020YFC2200901.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. developed the general concept of the article and the proposed algorithm. X.S. developed the simulation code and conceived the experiment. S.M. performed the calculations and drew conclusions. W.Y. provided the experimental equipment and prepared Fig.5 and 6. Z.F. and Z.C. modified the algorithm. H.L. modified the article and secured funding. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Shi, X., Meng, S. et al. Adaptive hierarchical filtering particle swarm optimization for multiple magnetic dipoles modeling of space equipment. Sci Rep 15, 33946 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10406-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10406-2