Abstract

The use of cow bone biochar for improving soil chemical properties and tomato quality and shelf life remains relatively unexplored. This study aimed to evaluate the effects of biochar on soil chemical properties, growth, yield, quality and shelf life of tomato. The experiment, conducted over a period of 120 days, comprised five levels (0, 10, 20, 30, and 40 t ha⁻¹) of cow bone biochar arranged in a completely randomised design replicated three times. Results indicated that cow bone biochar increased soil chemical properties, growth, yield, quality, shelf life and the percentage weight loss of tomato fruits relative to the control. The 40 t ha−1 biochar level increased yield of tomato by 22%, 97%, 162 and 294%, respectively relative to 30 t ha−1, 20 t ha−1, 10 t ha−1 and the control. Also, relative to 30, 20, 10 t ha−1 biochar and control, application of biochar at 40 t ha−1 increased shelf life of tomato by 12%, 23%, 28% and 70% respectively. These findings showed that biochar increases soil productivity, leading to improved tomato yield, quality, and shelf life. Further research is needed to determine if higher biochar rates can yield even greater benefits or if improvements level off beyond 40 t ha⁻¹.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biochar, a carbon-rich byproduct produced from the thermal decomposition of organic materials through pyrolysis, has attracted considerable attention as a soil amendment with significant potential to improve soil quality and enhance crop yields. Its unique properties, such as high porosity, large surface area, and the ability to retain nutrients and water, make biochar particularly beneficial for agricultural soils, especially in degraded or nutrient-poor environments1.

Biochar was initially utilized by pre-Columbian indigenous peoples in the Amazon region between 500 and 9,000 years ago2 as one of several soil amendments that led to the creation of ‘terra preta,’ a nutrient-rich agricultural soil with a higher pH than the region’s typically acidic and unproductive soils3. The addition of biochar can improve soil structure, enhance porosity, raise pH, increase electrical conductivity, boost water retention, and enhance cation exchange capacity. It also improves nutrient retention, organic carbon levels, available phosphorus, and total carbon and nitrogen concentrations, while decreasing soil bulk density, nutrient loss, and the bioavailability of heavy metals4,5,6. Furthermore, biochar supports the growth and activity of beneficial microbial populations and soil enzymes, and it can help suppress soil pathogens7,8.

The application of biochar in agriculture can result in increased crop yields by improving nutrient use efficiency and soil fertility9. For instance, its ability to increase soil organic carbon and provide a stable environment for beneficial microorganisms supports better plant growth and resilience to environmental stresses, such as drought10. Additionally, biochar’s capacity to sequester carbon in the soil contributes to climate change mitigation, making it a promising tool for sustainable agriculture11.

Despite the numerous benefits of biochar, its effectiveness can vary depending on factors such as the type of feedstock used, pyrolysis conditions, and soil characteristics. Understanding these factors is essential for optimizing biochar’s potential in improving soil health and boosting crop productivity across different agricultural systems.

In Nigeria, approximately 42 million sheep, 18 million cattle, 7.5 million pigs, and 1.4 million equines are slaughtered annually12. Globally, slaughterhouses generate around 130 billion kilograms of animal bone waste each year, with Nigeria contributing over 8% to this total13,14. According to Ritchie15, bones account for 40% of the total by-products derived from livestock processing in Nigerian slaughterhouses. The country produces about 5 million tonnes of cow bones annually, but efficient disposal methods remain lacking, with burning and indiscriminate dumping being the predominant practices16. This highlights the urgent need for improved bone waste management systems, and converting these residues into biochar presents a potential solution.

Cow bone biochar is a type of biochar made from the pyrolysis of cow bones. Unlike typical biochar, which is made from plant materials like wood or crop residues, cow bone biochar is derived from animal bones. It is a rich source of calcium phosphate (Ca₃(PO₄)₂), which is essential for improving soil calcium levels. Calcium plays a critical role in soil structure and nutrient exchange. Higher calcium levels in crops strengthen cell walls, leading to firmer fruits with longer shelf life17. This helps reduce post-harvest losses and improves the overall marketability of crops.

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) is a crucial vegetable crop globally, offering significant nutritional and economic benefits. It is widely cultivated in many countries, ranking second only to potatoes in importance within the vegetable sector18. By 2013, global tomato production reached approximately 163 million tons due to its value in both nutrition and the economy19. Tomatoes are consumed in various forms—fresh, in salads, soups, juices, ketchup, pastes, and purees20. Nutritionally, tomatoes are rich in vitamins A and C, minerals, sugars, essential amino acids, iron, fiber, and phosphorus21. They also contain lycopene, a carotenoid known for its antioxidant properties, which has been linked to the prevention of diseases such as cancer22 and cardiovascular conditions23.

In Nigeria, the increase in population growth and development has spurred a rising demand for the consumption and marketing of tomatoes. Despite this demand, tomatoes are a perishable vegetable crop with a shelf life of approximately one week at ambient temperature24. Consequently, various storage and preservation methods are employed to maintain the harvested fruits in an edible state for an extended period. These include the use of hydrogen sulfide25, chitosan coating26, abscisic acid27, and essential oils28. Past research has demonstrated that the application of CaCl₂ reduces fruit decay and enhances tissue and cell wall hardness29.

In a study by Shehata et al.30, the impact of calcium chloride (CaCl₂), chitosan, hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), and ozonated water on the storage and quality of tomato fruit (Solanum lycopersicum L. cv. 448) stored at 10 °C for 28 days was investigated. The results indicated that all tested treatments significantly prolonged the shelf life and preserved the quality of tomato fruit compared to the control group. Among them, chitosan and CaCl₂ emerged as the most effective treatments for maintaining quality attributes. While CaCl₂, abscisic acid, chitosan, H₂O₂, and ozonated water offer potential benefits for tomato post-harvest storage, their use comes with significant drawbacks that cannot be overlooked. These include food safety concerns, environmental and health risks, potential negative impacts on sensory quality, and economic inefficiency. As a result, the application of calcium has garnered increased attention due to its capacity to delay the ripening of fruits and vegetables, extend their senescence, and maintain quality31. This underscores the potential for manipulating the shelf life of tomatoes through soil amendments such as cow bone biochar.

However, the application of cow bone biochar for enhancing the shelf life of tomatoes has not been tested. Biochar has been known to improve soil properties32. Almaroai and Eissa33 found that the application of cow bone biochar at rates of 5 and 10 t ha⁻¹ significantly increased tomato fruit yield by 20 and 30%, respectively, compared to the control treatment. Furthermore, cow bone biochar led to a 33% increase in total acidity, a 29% increase in total soluble solids, and a 39% increase in vitamin C and lycopene levels in tomato juice compared to the control. To provide a comprehensive understanding of the impact of biochar on soil chemical properties, as well as the growth, yield, quality, and shelf life of tomatoes, this study seeks to address an existing knowledge gap. Accordingly, the objective of this study was to assess the effects of different levels of cow bone biochar on soil chemical properties, growth, yield, quality, and shelf life of tomato.

Based on these objectives, it was hypothesized that soil properties, as well as the growth, yield, quality, and shelf life of tomatoes, would respond differently to cow bone biochar applied at varying rates.

Results

Soil and biochar characterization

Table 1 shows the results of the soil potted in grow bags before experimentation and the chemical analysis of the cow bone biochar used. The particle size analysis indicated that the soil was sandy loam in texture, with high sand content and low values for both silt and clay. The soil pH in water was 5.45, indicating strong acidity. The soil was low in organic matter (2.48%), total N (0.10%), available P (4.99 mg kg⁻¹), Ca (1.70 cmol kg⁻¹), and Mg (0.30 cmol kg⁻¹), but adequate in exchangeable K (0.19 cmol kg⁻¹) according to the critical levels of 3.0% organic matter, 0.20% N, 10.0 mg kg⁻¹ available P, 0.16–0.20 cmol kg⁻¹ K, 2.0 cmol kg⁻¹ exchangeable Ca, and 0.40 cmol kg⁻¹ exchangeable Mg recommended for crop production in the ecological zones of Nigeria. The cow bone biochar had a pH of 7.41, indicating a slightly alkaline nature. The biochar contained relatively high organic carbon content (59.5%), suggesting its potential to enhance soil carbon levels. Additionally, it contained nitrogen (1.37%), phosphorus (0.61%), potassium (0.92%), calcium (5.00%), magnesium (2.60%), and sodium (0.61%). The carbon-to-nitrogen (C: N) ratio of the biochar was 43.43 (Table 1).

Effect of biochar levels on soil chemical properties

The effects of different biochar levels on soil chemical properties are presented in Table 2. Biochar application significantly (p < 0.05) increased soil chemical properties (organic matter, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium) relative to the control. There was an increase in soil chemical properties as the biochar levels increased from 0 to 40 t ha−1. At Site A, application of 40 t ha⁻¹ biochar increased soil organic matter (SOM) by 130.2% and soil nitrogen by 33.3% compared to the control. Similarly, at Site B, SOM and nitrogen increased by 126.8% and 33.3%, respectively. Plots that received 10, 20, and 30 t ha⁻¹ of biochar showed statistically similar values for both SOM and nitrogen, indicating a plateau in response beyond a certain threshold. Likewise, plots treated with 30 t ha⁻¹ and 40 t ha⁻¹ biochar levels showed statistically similar values for Mg. For P, K, Ca, and Mg, the nutrient levels followed a consistent increasing trend in the order: 40 t ha⁻¹ > 30 t ha⁻¹ > 20 t ha⁻¹ > 10 t ha⁻¹. On average, across both sites, biochar applications of 40, 30, 20, and 10 t ha⁻¹ enhanced calcium availability by 995.2%, 783.8%, 629.8%, and 565.4%, respectively, relative to the control.

Effect of biochar levels on tomato growth and yield parameters

Results of the effect of biochar on tomato growth and yield parameters are presented in Table 3. Biochar application consistently enhanced plant height, stem diameter, number of leaves, number of fruits, and fruit yield compared to the control, with increases generally proportional to the biochar rate. At both sites, plant height increased by 14–76%, while stem diameter improved by 17–72% depending on the treatment level. The number of leaves showed modest gains, ranging from 1–8%, with statistically similar values observed among 10, 20, 30 and 40 t ha−1 biochar rates at site A and site B and between the control and 10 t ha⁻¹. In terms of reproductive parameters, the number of fruits increased by 57.1% and 50.0% for site A and site B, respectively compared with the control. Yield gains were especially pronounced at 40 t ha⁻¹, where increases reached 289% at Site A and 300% at Site B relative to the control. There were increases in growth and yield parameters when biochar was increased from 0 to 40 t ha−1 levels. However, the stem diameter values for the 10 t ha−1 and 20 t ha−1 biochar levels at site B are statistically similar with 10 t ha−1 and 20 t ha−1 biochar levels having an increase of 21.1 and 31.6%, respectively relative to the control. Additionally, the number of leaves for the control, 10 t ha−1, 20 t ha−1, and 30 t ha−1 biochar levels at site A are also statistically similar with 10 t ha−1, 20 t ha−1, and 30 t ha−1 biochar levels having an increase of 1.2%, 3.5% and 4.7%, respectively relative to the control. There were no significant differences observed (p < 0.05”) in number of leaves between control and 10 t ha⁻¹ biochar level, and between 10, 20, 30, and 40 t ha⁻¹ biochar level for site B.

Effect of biochar levels on mineral and proximate contents of tomato fruit

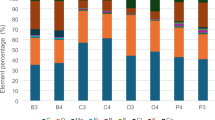

Mineral content

Results of the effects of biochar levels on mineral contents of tomato fruit are presented in Table 4. Application of biochar increased Na, Cu, Fe, Ca, Zn and Mg contents of tomato relative to the control. The increase in the mineral content of tomato by biochar was from 0 to 40 t ha−1 level. The 40 t ha−1 biochar level increased Na, Cu, Fe, Mg Ca and Zn by 60.71, 142.93, 68.13, 328.4, 68.75% and 184.2%, respectively relative to the control. (Fig. 1).

Proximate content

The effects of biochar levels on the moisture contents of tomato fruits are presented in Fig. 2. Biochar increased moisture content of tomato fruits relative to the control however, the 10, 20, 30 and 40 t ha−1 levels have statistically similar values. At Site A, biochar application rates of 40 t ha⁻¹, 30 t ha⁻¹, 20 t ha⁻¹, and 10 t ha⁻¹ increased tomato fruit moisture content by 7.35%, 5.55%, 5.40%, and 4.72%, respectively, compared to the control. At Site B, the corresponding moisture increases were 6.79%, 5.54%, 5.26%, and 4.04%.

The effect of biochar levels on fat content of tomato fruit are presented in Fig. 3, while the effect of biochar levels on carbohydrate, ash and protein contents are respectively presented in Figs. 4, 5 and 6. Biochar reduced the fat, carbohydrate and ash contents and increase the protein content of tomato fruit relative to the control. At Site A, biochar application rates of 40 t ha⁻¹, 30 t ha⁻¹, 20 t ha⁻¹, and 10 t ha⁻¹ reduced the fat contents of tomato fruit by 64.6%, 33.1%, 16.0%, and 7.1%, respectively, compared to the control. At Site B, the corresponding tomato fruits fat reduction were 72.8%, 28.1%, 13.4%, and 7.2% (Fig. 3). Also, at Site A, biochar application rates of 40 t ha⁻¹, 30 t ha⁻¹, 20 t ha⁻¹, and 10 t ha⁻¹ reduced the carbohydrate contents of tomato fruit by 43.3%, 29.5%, 19.1%, and 9.8%, respectively, compared to the control. At Site B, the corresponding tomato fruits carbohydrate reduction were 74.1%, 28.6%, 22.6%, and 8.8% (Fig. 4). In the same vein, at Site A, biochar application rates of 40 t ha⁻¹, 30 t ha⁻¹, 20 t ha⁻¹, and 10 t ha⁻¹ reduced the ash contents of tomato fruit by 90.5%, 90.5%, 171.1%, and 62.1%, respectively, compared to the control. At Site B, the corresponding tomato fruits ash reduction were 39.2%, 51.2%, 71.8%, and 37.5% (Fig. 5). The order of increasing protein content was 40 t ha−1 > 30 t ha−1 >20 t ha−1 > 10 t ha−1 > control, the reverse was for ash, carbohydrate and fat contents. At Site A, biochar application rates of 40 t ha⁻¹, 30 t ha⁻¹, 20 t ha⁻¹, and 10 t ha⁻¹ increased the protein contents of tomato fruit by 146.8%, 87.6%, 39.3%, and 13.0%, respectively, compared to the control. At Site B, the corresponding tomato fruits protein increase were 216.7%, 191.6%, 159.1%, and 64.4% (Fig. 6). The effect of biochar levels on fibre content of tomato fruit are presented in Fig. 7. The fibre content of tomato fruits showed a non-linear response to biochar application across both sites. At site A, fibre increased significantly (p < 0.05) from 1.54% in the control to a peak of 3.01% at 20 t/ha, followed by a decline to 2.99% at 30 t ha−1 and a sharp drop to 1.13% at 40 t ha−1. A similar trend was observed at site B, where fibre content rose from 1.97% (control) to a maximum of 3.25% at 20 t ha−1, then declined to 1.21% at 30 t ha−1 and slightly recovered to 1.29% at 40 t ha−1.

Effect of biochar on shelf life of tomato fruits

The results of the effect of biochar on shelf life of tomato fruits are presented in Table 5. Biochar increased the shelf life of tomato relative to the control. Biochar application significantly (p < 0.05) reduced weight loss in tomatoes compared to the control. The 40 t ha⁻¹ biochar level resulted in the longest shelf life of tomato. Weight loss and shelf life of tomato showed no significant differences (p < 0.05) between 10 and 20, and between 20 and 30 t ha⁻¹ biochar levels. Averaging the two sites, the 40 t ha−1 biochar reduced weight loss by 12.38, 16.70, 19.06 and 41.70%, respectively 30, 20, 10 t ha−1 biochar and control. Also, relative to 30, 20, 10 t ha−1 biochar and control, application of biochar at 40 t ha−1 increased shelf life of tomato by 11.99, 23.39, 27.73 and 70.31% respectively.

Discussion

Effect of biochar levels on soil chemical properties

The application of biochar to soils increases the levels of organic matter, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium contents of the soil. Soils amended with cow bone biochar showed higher organic carbon content, likely due to the high concentration of stable carbon compounds in the biochar32. When applied to the soil, it contributes directly to the overall SOM. Since biochar is highly resistant to decomposition, it remains in the soil for a long period, acting as a long-term carbon store. Gwenzi et al.34 stated that about 2.2 M t year−1 of organic carbon can be added using biochar. In this experiment, biochar treatments have increased soil N relative to the control. While cow bone biochar may not be inherently rich in nitrogen, it enhances nitrogen retention by reducing leaching and volatilization, promoting microbial activity, and improving soil structure35,36—all of which contribute to greater nitrogen availability. This is consistent with findings by Nigussie et al.36 and Abdeen37who observed similar nitrogen increases using plant-based biochars.

Phosphorus levels also increased significantly in biochar-amended soils. Cow bone biochar is naturally rich in phosphorus, primarily in the form of calcium phosphate. The pyrolysis process preserves much of this phosphorus, making it readily available upon incorporation into soil. Furthermore, biochar reduces P leaching, thereby enhancing long-term phosphorus retention and availability38. These mechanisms explain the elevated P concentrations observed in treated soils in this study.

Importantly, all treatments in this study received a basal application of NPK 15-15-15 fertilizer, ensuring a uniform baseline of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium across all plots. Biochar’s porous structure and high cation exchange capacity likely enhanced nutrient retention and reduced leaching of the applied NPK nutrients. This synergistic effect may have led to greater nutrient availability and uptake compared to the control, where NPK was applied without biochar.

Cow bone biochar increased K, Ca and Mg contents of the soil because cow bones naturally contain significant amounts of calcium, magnesium and potassium. During the pyrolysis process, these minerals are concentrated in the biochar. When cow bone biochar is applied to the soil, it acts as a direct source of K, Ca, and Mg, gradually releasing these nutrients over time39,40. Secondly, biochar improves the soil’s cation exchange capacity (CEC), which is its ability to hold onto positively charged ions like K⁺, Ca²⁺, and Mg²⁺41. By increasing CEC, biochar helps retain these nutrients in the soil, preventing them from being leached away by water. Biochar particles possess colloidal properties, characterized by a high specific surface area and negative surface charges due to deprotonated functional groups42. This allows nutrients dissolved in soil solutions to be attracted to the biochar surfaces. Additionally, biochar’s ability to adsorb both cations and anions helps reduce the leaching of applied and inherent soil nutrients43. The observed improvement in soil chemical properties with increasing biochar application rates, from 0 to 40 t ha⁻¹, reflects the biochar’s distinct characteristics—such as its high porosity, large surface area, cation exchange capacity, and gradual nutrient release—which become more effective as the biochar concentration in the soil rises. This finding aligns with the study by Njoku et al.44where the application of rice husk and sawdust biochars at the highest rate (10 t ha⁻¹) resulted in increased values of pH, nitrogen, potassium, organic carbon, magnesium, sodium, and cation exchange capacity. Similarly, Adekiya et al.45 also demonstrated that soil chemical properties improved with biochar application, and this enhancement intensified with higher biochar rates.

Effect of biochar levels on tomato growth and yield parameters

Biochar increased the growth and yield of tomato because cow bone biochar increased the availability of essential nutrients in the soil, such as nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), and magnesium (Mg). These nutrients are critical for tomato growth, flowering, and fruit development. Biochar also enhances the soil’s cation exchange capacity (CEC)41helping to retain nutrients in the root zone and making them available to plants over a longer period, which leads to better overall plant health and higher yields.

Biochar helps reduce nutrient losses by leaching46,47,48,49. Nutrients such as nitrogen and potassium are held within the biochar structure and gradually released over time. This ensures that tomato plants have a steady supply of nutrients throughout the growing season, supporting both growth and yield.

Furthermore, biochar has a highly porous structure (Table 1), which enhances the soil’s ability to retain water50. Better water retention reduces the stress on tomato plants, leading to more consistent growth and higher yields. Tomato plants have high water requirements, especially during fruiting, so biochar helps provide a more stable water supply. The porous nature of biochar also helps to improves soil structure, increasing aeration and root penetration. Healthy root systems can access more nutrients and water, leading to more vigorous plant growth and better fruit yields.

Several studies44,45,51,52,53 have shown that biochar improves nutrient retention and crop productivity in tomatoes, maize, and rice under varying soil conditions. Results also indicated that biochar application significantly increased tomato yield by 29.55%54. Castañeda et al.55 observed a significant increase in tomato plant height when biochar was applied. Similarly, Calcan et al.56 reported that biochar with a strong alkaline pH of 9.89, produced through the slow pyrolysis of vine pruning residues, had a notable positive impact on the growth of tomato plants grown in highly acidic soil (pH = 5.40).

Effect of biochar levels on mineral and proximate contents of tomato fruit

The response of mineral concentrations of tomato to application of biochar was consistent with the values of soil chemical properties recorded for these treatments. There was increased nutrient availability in the soil as a result of application of biochar leading to increased up take by tomato plants. This finding aligns with existing research indicating that organic amendments, such as biochar, can enhance nutrient concentrations in plant tissues57,58. Biochar helps reduce nutrient leaching and increases the availability of key minerals like Na, Cu, Fe, Ca, Zn and Mg for plant uptake and therefore presence in the fruits. Biochar increases the soil’s cation exchange capacity41allowing it to hold onto more positively charged nutrients (like Ca²⁺, K⁺, Mg2+, Zn²⁺). This ensures these essential nutrients remain available in the root zone for absorption by tomato plants.

The application of biochar to soil affects the moisture, protein, fat, and carbohydrate contents of tomato fruits through a variety of mechanisms related to improved soil health and plant nutrient dynamics. Therefore, by maintaining stable moisture levels, biochar can reduce water stress on the plants. This creates more favorable growing conditions for the development of water-rich fruit like tomatoes.

Enhanced soil conditions due to biochar application brings about increase in protein content of tomato fruit in this experiment. Adequate nitrogen supplies due to biochar enable the plant to accumulate amino acids and proteins in its vegetative tissues. These are eventually translocated to the fruits as the plant shifts its energy toward reproductive growth, increasing the protein content in the tomato fruit. Nitrogen is a key component of amino acids, the building blocks of proteins59. Adequate nitrogen supply directly supports the synthesis of proteins in tomato fruits. SOM which was improved due to biochar serves as a reservoir of nutrients, including nitrogen, phosphorus, and micronutrients. When SOM decomposes, it releases nitrogen in plant-available forms, such as ammonium (NH₄⁺) and nitrate (NO₃⁻), which are essential for amino acid and protein synthesis. It has been reported that an increase in SOM content of the soil can improve tomato fruit quality60. Li et al.61 also found that SOM is positively correlated with protein content in tomato fruit. Usman et al.62 also found that biochar increased the protein content of tomato fruit.

The reduced fat contents of tomato fruits in the biochar applied plots relative to the control could be due to improved soil conditions and water availability created by biochar which might have shifted the plant’s metabolic focus toward growth and protein synthesis rather than the production of fats. Tomatoes naturally have low fat content63and this shift in nutrient availability can further reduce fat accumulation. Blumenthal et al.64 also noted an inverse relationship between oil and protein content. Higher nitrogen application led to a decrease in oil content while increasing protein levels. This result contradicts that of Usman et al.62 who reported that application of biochar increased the fat content of tomato fruit. However, increasing protein due to available of N has also been reported to reduce oil content in some legumes such as soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) and groundnuts (Arachis hypogea)64.

The reduced carbohydrate content of tomato fruit relative to the control could be as a result of the fruit absorbs more water, its moisture content increases due to the applied biochar. This may cause a “dilution effect”, where the relative concentration of carbohydrates in the tomato is reduced, even though the total carbohydrate content might remain the same65. Chen et al.65 suggested that the reduced carbohydrate content in tomato fruits with high water content occurs because water influences substrate concentration, thereby regulating metabolic reactions within the fruit. Additionally, water serves as a solvent for soluble sugars, meaning that higher water content enhances the fruit’s capacity to dissolve these sugars. The increased carbohydrate content observed in the tomato fruits from the control plots was likely due to water stress, which has been shown to enhance AGPase activity66,67. This may occur through effects on the enzyme’s redox state and sugar signaling pathways68ultimately accelerating the starch biosynthesis rate. These findings underscore the role of fruit water content in regulating metabolic processes in tomato fruits65. Furthermore, numerous studies have demonstrated that water deficit during the ripening stage can enhance tomato fruit quality, primarily by increasing the concentration of soluble sugars69,70,71,72.

Biochar improves soil fertility by enhancing nutrient availability and soil structure45. This leads to increased plant growth and fruit development. As the overall biomass (organic and inorganic matter) of the tomato fruit increases, the concentration of mineral elements (which contribute to ash content) may get diluted73 these assumably caused the reduced ash contents of the tomato fruits relative to the control. Similarly, fiber content in tomato fruits increased with biochar application up to 20 t ha−1 but decreased at higher rates. The decrease at higher rate may possibly be due to nutrient dilution, altered plant metabolism, or a shift in resource allocation toward other growth or quality parameters. The peak response at 20 t ha−1 across both sites indicates this may be the optimal rate for enhancing fibre content in tomatoes under these conditions.

Effect of biochar on shelf life of tomato fruits

Biochar reduced weight loss and increased the shelf life of tomato because cow bone biochar is rich in minerals, particularly calcium and phosphorus (Table 1), which are essential for cell wall strength and integrity in plants74. Calcium, in particular, plays a crucial role in maintaining cell wall stability and structure, reducing the likelihood of physical damage or softening in tomatoes. Stronger cell walls delay degradation, extending the shelf life of tomatoes. Calcium helps maintain the firmness of tomatoes, reducing water loss and extending shelf life. This is due to the fact that: (1) Calcium is a vital component of the plant cell wall, where it binds with pectins to form calcium pectate75. This compound is a critical part of the middle lamella, which is the layer that cements neighboring plant cells together76. Stronger cell walls help maintain the structural integrity of the tomato fruit74making it less prone to mechanical damage, water loss, and microbial invasion. It has been reported that the uptake of exogenous calcium ions by strawberry increases the amount of chelate-soluble pectins, thus enhancing cell wall stability and preventing the dissolution of the middle lamella77,78. (2) Calcium stabilizes cell membranes by interacting with phospholipids, reducing the permeability of the cell membrane. This stabilization helps to maintain cellular structure and function, reducing the rate of water loss (transpiration) from the fruit during storage79. Lower water loss translates to less weight loss and longer shelf life. (3) Calcium has been shown to slow down the production of ethylene, a plant hormone that promotes ripening and senescence (aging)80. By delaying ethylene production, calcium helps to slow down the ripening process, thereby extending the shelf life of tomatoes. Slower ripening reduces the softening and over-ripening of fruits, which are major contributors to weight loss and spoilage. Sams and Conway80 also found that in the fruit of ‘Golden Delicious’ apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) high calcium concentrations resulted in a decrease in ethylene production. It has also been reported that calcium can preserve fruit firmness by slowing down the ripening and aging process, improving cold storage resistance by regulating reactive oxygen species levels, inhibiting post-harvest diseases, and maintaining overall fruit quality81,82,83. (4) Calcium inhibits the activity of enzymes like polygalacturonase and pectin methylesterase84which break down pectin in the cell walls during ripening. By inhibiting these enzymes, calcium helps to maintain the structural integrity of the cell walls, delaying softening and reducing the rate of degradation in storage. Also, cow bone biochar helps improve soil water retention, allowing the tomato plant to access a more consistent water supply due to the biochar’s high porosity (Table 1). This promotes steady fruit development, reducing fluctuations in fruit water content. Proper water balance in tomatoes prevents issues like fruit cracking and post-harvest dehydration85both of which can shorten shelf life.

Practical limitations of biochar application

The recommended application rate of biochar in this study (40 t ha−1) is notably high and labour-intensive. Applying such large quantities on even a small farm requires significant labour or machinery, both of which increase costs. Small-scale farmers, who often rely on manual labour, may struggle to meet these demands efficiently. Furthermore, excessive biochar can alter soil pH, leading to nutrient imbalances or toxicity, which may harm plant growth and soil microbial communities. Biochar can also significantly influence soil microbial communities, altering diversity, abundance, and functionality, there could be shifts in microbial dominance, favoring certain species over others (e.g., fungi vs. bacteria)86. Over time, fine biochar particles may also clog soil pores, reducing infiltration and aeration, potentially increasing soil compaction. Biochar’s stability can result in accumulation, especially in soils with limited organic matter turnover, further affecting soil structure and compatibility.

To address these challenges, tailoring biochar application rates to specific soil types and crop needs based on soil testing is critical87,88. Scaling down application rates to 5–10 t ha−1 would make biochar more feasible for small-scale use, as research indicates even lower rates can yield significant benefits over time89,90,91. Additionally, selecting biochar with particle sizes and porosity suited to the soil type can prevent pore clogging87,88while mixing biochar with organic matter (e.g., compost or manure) enhances its integration and maintains soil structure92. Utilizing locally available, low-cost biomass, such as agricultural waste, can significantly lower production expenses. Cooperative models, where farmers collectively invest in and share pyrolysis equipment, can further reduce per-farmer costs. Governments and development agencies can also support small-scale farmers by subsidizing biochar production, providing access to low-interest loans, or integrating biochar into broader agricultural extension programs.

To mitigate impacts on soil microbial communities, biochar should be applied incrementally over time to allow microbial populations to adapt. Combining biochar with organic amendments or cover crops can enhance microbial diversity, balance nutrient cycling, and sustain soil health. Through these strategies, biochar application can be optimized to achieve sustainable agricultural benefits without compromising environmental and economic feasibility.

To support widespread adoption, especially among smallholder farmers, it is essential to conduct cost–benefit analyses and pilot-scale field validations. These assessments would help determine whether the agronomic benefits of biochar application at various rates justify the associated labour, material, and equipment costs under local farming conditions. Real-world trials could also provide insights into region-specific biochar sourcing, production efficiencies, and long-term returns on yield and soil health improvements. Such data would inform tailored recommendations that align with the economic capacities of resource-constrained farmers, ultimately facilitating more practical and scalable integration of biochar into sustainable agricultural systems.

Conclusion

The results from present study demonstrated that cow bone biochar significantly improved soil chemical properties, enhanced tomato plant growth and yield, and improved fruit quality, including increased mineral content, moisture, protein levels, and shelf life. Concurrently, it reduced fat, ash, carbohydrate levels, and postharvest weight loss compared to the control. These effects were most pronounced at the highest application rate of 40 t ha⁻¹.

These findings suggest that cow bone biochar is a promising soil amendment for enhancing tomato productivity and postharvest quality in tropical soils. Future studies should investigate whether application rates above 40 t ha⁻¹ continue to offer additional benefits or if they result in diminishing returns. Moreover, since this study was conducted under controlled screen house conditions, field-based trials are essential to validate the findings under practical farming scenarios. Additionally, cost-effectiveness and long-term ecological impacts of large-scale application should be assessed to ensure sustainable adoption.

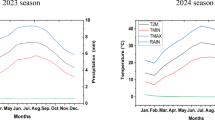

Materials and methods

In 2024, two simultaneous experiments were conducted at sites A and B within the same screen house between February and May at the Teaching and Research Farm of Bowen University, located in Iwo, Osun State, Nigeria to assess the effects of different levels of cow bone biochar on soil chemical properties, growth, yield, quality and shelf life of tomato. The experiment at site B was carried out concurrently with site A to verify the findings from site A. Bowen University is situated at coordinates 7.6236°N, 4.1890°E, with an elevation of 312 m above sea level. The green house features a galvanized iron frame, UV protection covering, insect-resistant side netting, and a granite-covered floor. Temperature and humidity inside the screen house were recorded using a thermograph and a barograph, averaging 31 °C and 75%, respectively. The soil in Iwo is classified as Oxic Haplustalf according to the USDA soil order Alfisol, or Luvisol by FAO classification.

Sample preparation and treatments

Soil samples were randomly collected from a depth of 0 to 15 cm around the Research Farm using a spade. The collected soil was mixed, sieved through a 2 mm mesh to remove stones and debris, and then 15 kg of the sieved soil was placed into perforated grow bags to ensure aeration and drainage. Each treatment consisted of four grow bags, which were placed randomly within the screen house to ensure an unbiased distribution of amendments, representing site A. An identical set of grow bags was placed adjacent to these within the same screen house, representing site B.

The experiment comprised five levels of cow bone biochar application: 0, 10, 20, 30, and 40 t ha⁻¹, arranged in a completely randomized design with three replications. These application rates were selected based on ranges commonly reported in previous studies evaluating biochar effects on soil fertility and crop productivity in southwest Nigeria92.

Preparation of soil amendments

The biochar used in this study was produced from cow bones obtained from the abattoir in Iwo town. These bones were collected and left to dry before undergoing pyrolysis. To initiate the process, the bones were tightly packed into a locally fabricated metal drum kiln equipped with small holes at the base for gas release during pyrolysis (Fig. 1). The drum is equipped with a vertical chimney for smoke release. The temperature during the process of burning was checked with a thermocouple and it was approximately 500 °C. After pyrolysis, the biochar was allowed to cool, then ground and sieved through a 2 mm mesh for uniformity before use32.

Application of soil amendments

Quantities of 75 g, 150 g, 225 g, and 300 g of cow bone biochar were incorporated into 15 kg of soil in the grow bags to represent 10, 20, 30, and 40 t ha⁻¹ biochar application rates, respectively. A treatment without biochar (0 g) served as the control. The cow bone biochar was incorporated into the soil using hand trowel and allowed for four weeks before transplanting tomato seedlings into the grow bags. Watering was done immediately and continued every other day till the day of transplanting.

Nursery and transplanting of tomato

In this experiment, a local variety of tomato (Iwo local) was utilized. The tomato seed was purchased from the market and sown in a seed tray filled with good loamy soil in the screen house. Watering was done daily in the evening. After three weeks in the nursery, transplanting was done. During transplanting, which occurred in the evening, seedlings was carefully moved with a ball of earth to minimize root damage. Each grow bag received one tomato seedling. One healthy plant was maintained per grow bag and four grow bags represent a treatment and there were 20 plants per block and 60 plants in site A and 60 plants in site B. Immediately, watering was done and subsequent morning watering sessions was implemented to maintain water content close to field capacity throughout the experiment’s duration. At one week after transplanting, basal application of NPK 15-15-15 fertilizer was applied by ring method at the rate of 120 kg ha-1 which was equivalent to 0.18 kg per grow bag. Weeding was done by hand picking emerged weeds from each grow bag. For both crops, the experiment lasted for 120 days.

Determination of soil and biochar characteristics

Before treatments were applied, soil samples were collected using a core sampler and dried in an oven at 105 °C for 24 h to determine bulk density, following the method outlined by Campbell & Henshall93. Total porosity was then calculated using the bulk density and a particle density value of 2.65 g cm³. Additionally, soil samples were gathered, air-dried, and sieved through a 2 mm mesh to analyze their physical and chemical properties. The hydrometer method, as described by Gee & Or94was used to determine particle size distribution. Soil organic carbon (OC) was measured using the Walkley-Black method, involving dichromate wet oxidation as detailed by Nelson & Sommers95. Total nitrogen (N) was determined using the micro-Kjeldahl digestion method, based on Bremner96. Available phosphorus (P) was extracted using the Bray-1 method, with molybdenum blue colorimetry for detection, as per Frank et al.97. Exchangeable potassium (K), sodium (Na), calcium (Ca), and magnesium (Mg) were extracted using 1 M ammonium acetate, following Hendershot et al.98. Potassium was analyzed using a flame photometer, while sodium, calcium, and magnesium were measured with an Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer. After the treatments, soil samples from each treatment were air-dried, sieved, and tested for chemical properties using the same methods.

The bulk density of the biochar used was measured by filling a container of known weight and volume with the biochar, without compressing it. The container and biochar were weighed, and bulk density (bd) was calculated using the formula provided by Unal et al.99.

The solid density of the biochar was measured using the liquid displacement method as described by Unal et al.99. Following this, the porosity of the biochar was calculated using the formula provided by Keawpoolphol et al.100.

bd = bulk density of biochar

sd = solid density of biochar

Additionally, the biochar used in the experiment was analyzed to determine their nutrient content. The biochar was air-dried, sieved through a 2 mm mesh, and tested for organic carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, sodium, and magnesium in accordance with AOAC101 standards.

Determination of growth and yield components of tomato

Three tomato plants were randomly selected from each treatment group to assess growth parameters, including plant height, stem diameter, and the number of leaves per plant, at the mid-flowering stage (approximately 28 days after transplanting). Plant height was measured from the base to the shoot tip using a meter rule, the number of leaves was counted manually, and stem diameter was measured with a vernier caliper. Mature and ripe fruits were harvested and counted, with tomato yields determined by the weight of the harvested fruits up to 100 days after transplanting.

Shelf-life determination of tomato fruits

The first set of tomato fruits harvested, were cleaned with a clean cloth after which they were sorted into different treatment groups with each group containing five (5) fruits and three replicates. They were then properly arranged on a clean table in the laboratory to determine their shelf lives.

Parameters accessed include:

-

(i).

Weight loss: The weight of each tomato fruit was taken soon after harvesting and during each experimental day using a weighing balance. The total weight loss was calculated by taking the difference between the initial and final weight (at five (5) days interval till full deterioration) of the fruits during the storage interval using the formula below which was expressed in percentage.

WL = Weight loss.

-

(ii).

Shelf life.

This was carried out by counting the number of days from the day of harvesting the tomato, to the day it was considered bad and below marketable condition.

Determination of mineral and proximate components of tomato fruits

Matured tomato fruits of uniform size were selected per treatment at harvest for chemical analysis to determine their mineral compositions, following the guidelines outlined by AOAC101. For this analysis, one gram of each sample was subjected to digestion using a mixture of HNO3, H2SO4, and HClO4 (7:2:1 v/v/v), with the subsequent determination of mineral compositions, including Cu, Fe, Mg, K, Ca, and Na, through atomic absorption spectrophotometry.

Simultaneously, samples of matured tomato fruits from each treatment were collected for proximate analysis. Utilizing standard chemical methods specified by the Association of Analytical Chemists101the moisture, crude fiber, crude protein, crude fat, and carbohydrate contents of the tomato fruits was assessed. The moisture content was determined by drying 2 g of each sample at 105 °C until a constant weight was achieved. To evaluate the fat content, the Soxhlet extraction technique using petroleum ether (40–50 °C) was employed. The crude protein content was ascertained through the micro-Kjeldahl digestion and distillation method102while the carbohydrate content was estimated following the method outlined in a study by Muller & Tobin103.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using ANOVA in SPSS104. Treatment means were compared using Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) at a 5% probability level.

Data availability

All datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are included in this article.

References

Lehmann, J. & Joseph, S. Biochar for Environmental Management: Science, Technology and Implementation (Earthscan, 2015).

Solomon, D. et al. Molecular signature and sources of biochemical recalcitrance of organic C in Amazonian dark earths. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 71, 2285–2298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2007.02.014 (2007).

Lehmann, J. et al. Classification of Amazonian dark earths and other ancient anthropic soils. In Amazonian Dark Earths: Origin, Properties, Management (eds Lehmann, J., Kern, D. C., Glaser, B. et al.) 77–102 (Springer, 2007).

Haider, F. U. et al. An overview on Biochar production, its implications, and mechanisms of Biochar-induced amelioration of soil and plant characteristics. Pedosphere 32, 107–130 (2022).

Malyan, S. K. et al. Biochar for environmental sustainability in the energy-water-agroecosystem nexus. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 149, 111379 (2021).

Hussain, Z. et al. Response of mung bean to various levels of biochar, farmyard manure and nitrogen. Soil. Syst. 13 (1), 26–33 (2017).

Bonanomi, G. et al. Biochar as plant growth promoter: better off alone or mixed with organic amendments? Front. Plant. Sci. 8, 1570. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.01570 (2017).

Jones, D. L., Rousk, J., Edwards-Jones, G., DeLuca, T. H. & Murphy, D. V. Biochar-mediated changes in soil quality and plant growth in a three year field trial. Soil Biol. Biochem. 45, 113–124 (2012).

Zhang, A. et al. Effect of Biochar amendment on yield and methane and nitrous oxide emissions from a rice paddy from Tai lake plain. China Agriculture Ecosyst. & Environ. Volume. 139 (4), 15: 469–475 (2010).

Kammann, C., Linsel, S., Gößling, J. W. & Koyro, H-W. Influence of Biochar on drought tolerance of Chenopodium quinoa willd and on soil-plant relations. Plant. Soil. 345 (1), 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-011-0771-5 (2011).

Woolf, D., Amonette, J. E., Street-Perrott, F. A., Lehmann, J. & Joseph, S. Sustainable biochar to mitigate global climate change. Nat. Commun. 1 56. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1053 (2010).

FAOSTAT (Food and Agriculture Organization Corporate Statistical Database). Africa Sustainable Livestock 2050. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QA (2019).

Blench, R. The Nigerian National livestock resource survey: A personal account. In: Baroin, C. and Jean, B., Eds., Man and Animal in the Lake Chad Basin, Paris: IRD, Mega-Chad Network, Symposium 627–648 (Orléans (FRA), 1999).

Clark, M. & Tilman, D. Comparative analysis of environmental impacts of agricultural production systems, agricultural input efficiency, and food choice. Environ. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa6cd5 (2017). 12, Article ID: 064016.

Ritchie, H., Meat & production, D. https://ourworldindata.org/meat-production (2017).

Falade, F., Ikponmwosa, E. & Fapohunda, C. Potential of pulverized bone as a pozzolanic material. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 3 (7), 1–6 (2012).

Melcrová, A. et al. The complex nature of calcium cation interactions with phospholipid bilayers. Sci. Rep. 6, 38035 (2016).

Chapagain, B. P. & Wiesman, Z. Effect of potassium magnesium chloride in the fertigation solution as partial source of potassium on growth, yield and quality of greenhouse tomato. Sci. Hort. 99 (3), 279–288 (2004).

FAOSTAT 2014. Global Tomato Production in 2013 (FAO, 2014).

Adedeji, O., Taiwo, K., Akanbi, C. & Ajani, R. Physico-chemical properties of four tomato cultivators grown in Nigeria. J. Food Proc. Preser. 30 (1), 79–86 (2006).

Ayandiji, A., Adeniyo, O. R. & Omidiji, D. Determinant postharvest losses among tomato farmers in Imeko-Afon local government area of Ogun state, Nigeria. Global Journal Sci. Frontier Research. 11 (5), 0975–5896 (2011).

Basu, A. & Imrhan, V. Tomatoes’ versus lycopene in oxidative stress and carcinogenesis: conclusions from clinical trials. Eur. J. Clin. Nutri. 61 (3), 295–303 (2007).

Freeman, B. B. & Reimers, K. Tomato consumption and health: emerging benefits. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 5 (2), 182–191 (2010).

Znidarcic, D. & Požrl, T. Comparative study of quality changes in tomato cv. ‘Malike’ (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) whilst stored at different temperatures. Acta Agriculturae Slov. 87 (2), 235–243. https://doi.org/10.14720/aas.2006.87.2.15102 (2006).

Yao, G. F. et al. Hydrogen sulfide maintained the good appearance and nutrition in Post-harvest tomato fruit by antagonizing the effect of ethylene. Front. Plant. Sci. 11, 584 (2020).

Zhu, Y. et al. Effect of Nano-SiOx/Chitosan complex coating on the physicochemical characteristics and preservation performance of green tomato. Molecules 24, 4552 (2019).

Tao, X. et al. Effects of exogenous abscisic acid on bioactive components and antioxidant capacity of postharvest tomato during ripening. Molecules 25, 1346 (2020).

Tzortzakis, N., Xylia, P. & Chrysargyris, A. Sage essential oil improves the effectiveness of Aloe vera gel on postharvest quality of tomato fruit. Agronom 9, 635 (2019).

El-Mogy, M. M., Parmar, A., Ali, M. R., Abdel-Aziz, M. E. & Abdeldaym, E. A. Improving postharvest storage of fresh artichoke bottoms by an edible coating of Cordia myxa gum. Postharvest Biol Technol. 163, 111143 (2020).

Shehata, S. A. et al. Extending shelf life and maintaining quality of tomato fruit by calcium chloride, hydrogen peroxide, chitosan, and ozonated water. Sci. Hort. 7, 309 (2021).

Guo, Q. et al. Curcumin-loaded pea protein isolate-high methoxyl pectin complexes induced by calcium ions: characterization, stability and in vitro digestibility. Food Hydrocoll. 98, 105284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.105284 (2020).

Adekiya, A. O., Adebiyi, O. V., Ibaba, A. L., Aremu, C. & Ajibade, R. O. Effects of wood biochar and potassium fertilizer on soil properties, growth and yield of sweet potato (Ipomea batata). Heliyon 8 e11728 (2022).

Almaroai, Y. A. & Eissa, M. A. Effect of Biochar on yield and quality of tomato grown on a metal-contaminated soil. Sci. Hortic. 265, 109210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109210 (2020).

Gwenzi, W., Chaukura, N., Mukome, F. N., Machado, S. & Nyamasoka, B. Biochar production and applications in sub-Saharan africa: opportunities, constraints, risks and uncertainties. J. Environ. Manag. 150, 250–261 (2015).

Zhang, M., Liu, Y., Wei, Q. & Gou, J. Biochar enhances the retention capacity of nitrogen fertilizer and affects the diversity of nitrifying functional microbial communities in karst soil of Southwest China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 226, 112819 (2021).

Nigussie, A., Kissi, E., Misganaw, M. & Ambaw, G. Effect of Biochar application on soil properties and nutrient uptake of lettuces (Lactuca sativa) grown in chromium polluted soils. Am. -Eurasian J Agric. Environ. Sci. 12 (3), 369–376 (2012).

Abdeen, S. A. & Biochar Bentonite and potassium humate effects on saline soil properties and nitrogen loss. Ann. Res. Rev. Biol. 35 (12), 45–55 (2020).

Miller, J. S., Rhaodes, A. & Puno, H. K. Plant nutrient in biochar. Adv. Agro 125 (2012).

Bilias, F., Kalderis, D., Richardson, C., Barbayiannis, N. & Gasparatos, D. Biochar application as a soil potassium management strategy: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 858, 159782 (2023).

Alkharabsheh, H. M. et al. Biochar and its broad impacts in soil quality and fertility, nutrient leaching and crop productivity. Rev. Agron. 11, 993. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11050993 (2021).

Hailegnaw, N. S., Mercl, F., Pračke, K., Száková, J. & Tlustoš, P. Mutual relationships of Biochar and soil pH, CEC, and exchangeable base cations in a model laboratory experiment. J. Soils Sediments. 19, 2405–2416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-019-02264-z (2019).

He, X., Wang, Q., Jin, Y., Chen, Y. & Huang, L. Properties of Biochar colloids and behaviors in the soil environment: influencing the migration of heavy metals. Environ. Res. 247, 118340 (2024).

Major, J., Steiner, C., Downie, A. & Lehmann, J. Biochar effects on nutrient leaching. In Biochar for Environmental Management: Science and Technology (eds Lehmann, J. & Joseph, S.) 271–288 (Earthscan, 2009).

Njoku, C. et al. Effect of Biochar on selected soil physical properties and maize yield in an ultisol in Abakaliki southeastern nigeria. Global adv. Res. J. Agri Sci. 4 (12), 864–870 (2015).

Adekiya, A. O. et al. Biochar, poultry manure and NPK fertilizer: sole and combine application effects on soil properties and ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) performance in a tropical Alfisol. Open. Agric. 5, 30–39 (2020).

Hossain, M. K., Strezov, V., Chan, K. Y. & Nelson, P. F. Agronomic properties of wastewater sludge Biochar and bioavailability of metals in production of Cherry tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum). Chemosphere 78 (9), 1167–1171 (2010).

Jeffery, S., Verheijen, F. G. A., van der Velde, M. & Bastos, A. C. A quantitative review of the effects of Biochar application to soils on crop productivity using meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 144 (1), 175–187 (2011).

Lehmann, J. et al. Nutrient availability and leaching in an archaeological anthrosol and a ferralsol of the central Amazon basin: fertilizer, manure and charcoal amendments. Plant. Soil. 249 (2), 343–357 (2003).

Sohi, S., Lopez-Capel, E., Krull, E., Bol, R. & Biochar, climate change and soil: Areview to guide future research. Glen Osmond, Australia. CSIRO Land Water Sci. Rep. (2009).

Chintala, R. et al. Molecular characterization of biochars and their influence on Microbiological properties of soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 279, 244–256 (2014).

Akhtar, S. S., Li, G., Andersen, M. N. & Liu, F. Biochar enhances yield and quality of tomato under reduced irrigation. Agric. Water Manag. 138, 37–44 (2014).

Tartaglia, M., Arena, S., Scaloni, A., Marra, M. & Rocco, M. Biochar administration to San Marzano tomato plants cultivated under Low-Input farming increases growth, fruit yield, and affects gene expression. Front. Plant. Sci. 11, 1281 (2020).

Vaccari, F. et al. Biochar stimulates plant growth but not fruit yield of processing tomato in a fertile soil. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 207, 163–170 (2015).

Lei, Y. et al. Effects of Biochar application on tomato yield and fruit quality: A Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 16 (15), 6397. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16156397 (2024).

Castañeda, W., Toro, M., Solorzano, A. & Zúñiga-Dávila, D. Production and nutritional quality of tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum var. Cerasiforme) are improved in the presence of Biochar and inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizae. Am. J. Plant. Sci. 11, 426–436 (2020).

Calcan, S. I. et al. Eff. Biochar Soil. Prop. Tomato Growth Agronomy 12, 1824. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12081824 (2022).

Solaiman, Z. M., Shaf, M. I., Beamont, E. & Anawar, H. M. Poultry litter Biochar increases mycorrhizal colonisation, soil fertility and cucumber yield in a fertigation system on sandy soil. Agriculture 10 (10), 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10100480 (2020).

Olowoake, A. A., Abioye, T. A. & Ojo, A. Infuence of Biochar enriched with poultry manure on nutrient uptake and soil nutrient changes in Amaranthus caudatus. Afr. J. Org. Agric. Ecol. 5, 19–26 (2021).

Brady, N. C. & Weil, R. R. The Nature and Properties of Soils 14th edition. (Pearson Prentice Hall, 2008).

Jindo, K. et al. Impact of compost application during 5 years on crop production, soil microbial activity, carbon fraction, and humification process. Commun. Soil. Sci. Plant. Anal. 47, 1907–1919 (2016).

Li, F. et al. Impact of organic fertilization by the digestate from by-product on growth, yield and fruit quality of tomato (Solanum lycopersicon) and soil properties under greenhouse and field conditions. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 10, 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40538-023-00448-x (2023).

Usman, M. et al. Impact of Biochar on the yield and nutritional quality of tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum) under drought stress. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 103 (7), 3479–3488 (2023).

Ali, M. Y. et al. Nutritional composition and bioactive compounds in tomatoes and their impact on human health and disease: A review. Food 10 (1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10010045 (2021).

Blumenthal, J., Battenspenrger, D., Cassman, K. G., Mason, K. G. & Pavlista, A. Importance of nitrogen on crop quality and health. In: Nitrogen in the Environment: Sources, Problems and Management 2nd edition. Hatfield, J.L. and R.F. Folett (Eds.). (Elsevier, 2008).

Chen, J. et al. Fruit water content as an indication of sugar metabolism improves simulation of carbohydrate accumulation in tomato fruit. J. Exp. Bot. 71 (16), 5010–5026. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/eraa225 (2020).

Yin, Y. G. et al. Salinity induces carbohydrate accumulation and sugar-regulated starch biosynthetic genes in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L. Cv. ‘Micro-Tom’) fruits in an ABA- and osmotic stress independent manner. J. Exp. Bot. 61 (2), 563–574. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erp333 (2010).

Biais, B. et al. Remarkable reproducibility of enzyme activity profiles in tomato fruits grown under contrasting environments provides a roadmap for studies of fruit metabolism. Plant Physiol. 164, 1204–1221 (2014).

Tiessen, A. et al. Evidence that SNF1-related kinase and hexokinase are involved in separate sugar-signalling pathways modulating post-translational redox activation of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in potato tubers. Plant J. 35, 490–500 (2003).

Mitchell, J., Shennan, C., Grattan, S. & May, D. Tomato fruit yields and quality under water deficit and salinity. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 116, 215–221 (1991).

Veit-Köhler, U., Krumbein, A. & Kosegarten, H. Effect of different water supply on plant growth and fruit quality of Lycopersicon esculentum. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 162, 583–588 (1999).

Chen, J., Qiu, K. S. D. T., Guo, R., Chen, R. & P. & Quantitative response of greenhouse tomato yield and quality to water deficit at different growth stages. Agric. Water Manage. 129, 152–162 (2013).

Ripoll, J., Urban, L. & Brunel, B. Bertin, N. Water deficit effects on tomato quality depend on fruit developmental stage and genotype. Jo Urnal Plant. Physiol. 190, 26–35 (2016).

Vassilev, S., Baxter, D., Andersen, L. K., Vassileva, C. V. & Morgan, T. An overview of the organic and inorganic phase composition of biomass. Fuel 94 (1), 1–33 .

Segado, P., Domínguez, E. & Heredia, A. Ultrastructure of the epidermal cell wall and cuticle of tomato fruit (Solanum lycopersicum L.) during development. Plant. Physiol. 170 (2), 935–946 (2016).

Cybulska, J., Zdunek, A. & Konstankiewicz, K. Calcium effect on mechanical properties of model cell walls and Apple tissue. J. Food Eng. 102, 217–223 (2011).

Hepler, P. K. & Calcium A central regulator of plant growth and development. Plant. Cell. 17, 2142–2155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40093-019-0273-7 (2005).

Lara, I., García, P. & Vendrell, M. Modifications in cell wall composition after cold storage of calcium-treated strawberry (Fragaria × Ananassa Duch.) fruit. Postharvest Biol Technol. 34, 331–339 (2004).

Zhang, L., Zhao, S., Lai, S., Chen, F. & Yang, H. Combined effects of multrasound and calcium on the chelate-soluble pectin and quality of strawberries during storage. Carbohydr. Polym. 200, 427–435 (2018).

Melcrová, A. et al. The complex nature of calcium cation interactions with phospholipid bilayers. Sci. Rep. 6, 38035. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38035 (2016).

Sams, C. E. & Conway, W. S. Effect of calcium infiltration on ethylene production, respiration rate, soluble polyuronide content, and quality of ‘golden delicious’ Apple fruit. Amer. Soc. Hort Sci. 109 (1), 53–57 (1984).

Madani, B. et al. Preharvest calcium chloride sprays affect ripening of eksotikaii’ Papaya fruits during cold storage. Sci. Hort. 171, 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2014.03.032 (2014).

Al-Qurashi, A. D. & Awad, M. A. Postharvest gibberellic acid, 6-benzylaminopurine and calcium chloride dipping affect quality, antioxidant compounds, radical scavenging capacity and enzymes activities of ‘grand nain’ bananas during shelf life. Sci. Hort. 253, 187–194. (2019).

Gao, Q., Xiong, T., Li, X., Chen, W. & Zhu, X. Calcium and calcium sensors in fruit development and ripening. Sci. Hort. 253, 412–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2019.04.069 (2019).

Langer, S. E. et al. Calcium chloride treatment modifies cell wall metabolism and activates defense responses in strawberry fruit (Fragaria × ananassa, Duch). J. Sci. Food Agric. 99 (8). https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.9626 (2019).

Gidado, M. J. et al. Challenges of postharvest water loss in fruits: Mechanisms, influencing factors, and effective control strategies – A comprehensive review. J. Agric. Food Res. 17 101249 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. Biochar alters soil microbial communities and potential functions 3–4 years after amendment in a double rice cropping system. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 311, 107291 (2021).

Major, J. Guidelines on Practical Aspects of Biochar Application to Field Soil in Various Soil Management Systems. Guidelines for Biochar Application to Soil—International Biochar Initiative Ver. 1.0 9 1–23 (2020).

Aller, D. et al. Biochar Guidelines for Agricultural Applications: Practical Insights for Applying Biochar To Annual and Perennial Crops (United States Biochar Initiative, 2023).

Cong, M. et al. Long-term effects of Biochar application on the growth and physiological characteristics of maize. Front. Plant. Sci. 14, 1172425. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1172425 (2023).

Jiang, Y. et al. A global assessment of the long-term effects of Biochar application on crop yield. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 7, 100247 (2024).

Oni, B. A., Oziegbe, O. & Olawole, O. O. Significance of Biochar application to the environment and economy. Annals Agricultural Sci. 64 (2), 222–236 (2019).

Adekiya, A. O., Agbede, T. M., Aboyeji, C. M., Dunsin, O. & Simeon, V. T. Effects of Biochar and poultry manure on soil characteristics and the yield of radish. Sci. Hort. 243, 457–446 (2019).

Campbell, D. J. & Henshall, J. K. Bulk density. In Physical Methods of Soil Analysis (eds Smith, K. A. & Mullin, C. E.) 329–366 (Marcel Dekker, 1991).

Gee, G. W. & Or, D. Particle-size analysis. In Methods of Soil Analysis Part 4, ed. J. H. Dane and G. C. Topp, 255–93. (Madison, WI, USA: Physical Methods. Soil Science Society of America Book Series No. 5., 2002).

Nelson, D. W. & Sommers, L. E. Total carbon, organic carbon and organic matter. In Methods of Soil Analysis Part 3 – Chemical Methods (eds Sparks, D. L. et al.) 961–1010 (Soil Seince Society of America, 1996).

Bremner, J. M. Nitrogen-total. In Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 3. Chemical Methods 2nd edn (ed. Sparks, D. L.) 1085–1121 (ASA and SSSA, 1996).

Frank, K., Beegle, D. & Denning, J. Phosphorus. In Recommended Chemical Soil Test Procedures for the North Central Region, North Central Regional Research, ed. Brown J. R., Revised 21–26. (Columbia: Missouri Agric. Exp. Station. Publication No. 221., 1998).

Hendershot, W. H., Lalande, H. & Duquette, M. Ion exchange and exchangeable cations. Soil sampling and methods of analysis. In Canadian Society of Soil Science 2nd edn (eds Carter, M. R. & Gregorich, E. G.) 197–206 (CRC, 2007).

Unal, H., Isik, E., Izli, N. & Tekin, Y. Geometric and mechanical properties of mung bean (Vigna radiata L.) grain: effect of moisture. Int. J. Food Prop. 11, 585–599 (2008).

Keawpoolphol, P., Teamtuch, K., Asavasanti, S. & Tansakul, A. Development of porosity measurement apparatus for granular foods. The 19th food innovation asia conference (FIAC 2017). Innov. Food Sci. Tech. Mankind Empow. Res. Health Aging Soc. 546–552 (2017).

AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists. 19th edn, 2–15 (eds International, A. O. A. C.) (AOAC International, 2012).

Tomov, T., Rachovski, G., Kostadinova, S., Manolov, I. & Columbia Handbook of Agrochemistry 109 (2009).

Muller, H. G. & Tobin, G. Nutrition and food processing. London: Croom Helm 1980 (2019).

IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0. (IBM Corp., 2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors want to appreciate the management of Bowen University for financing the data collection of this work.

Author information

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adekiya, A.O., Ogunbode, T.O., Esan, V.I. et al. Short term effects of biochar on soil chemical properties, growth, yield, quality, and shelf life of tomato. Sci Rep 15, 24965 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10411-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10411-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Transforming extracted cashew nut shell into biochar and its application as soil amender for jute mallow (Corchorus olitorius L.) cultivation

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Synergistic effects of biochar and PGPR in enhancing the efficacy of biological control agents against Ganoderma boninense in oil palm (Elaeis guineensis L.): a critical review

Archives of Microbiology (2026)

-

Effects of biochar on soil properties as well as available and TCLP-extractable Cu contents: a global meta-analysis

Scientific Reports (2025)