Abstract

Globally, nest counts for many sea turtles now routinely exceed pre-conservation levels but also exhibit increased inter-annual variability. Mixed trend interpretations support population growth constraints but differ regarding why. Here we used a closed-loop population simulator to report generalized patterns of demographic change under assumptions of random variability that tended both above and below the null model scenario of no change over decades. Random changes in nine life history parameters spanning sea turtle hatching to eventual sexual maturity from 1950 through 2018 provided context for comparison with three decades of published nesting data for a globally important loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) population through 2018. Six demographic metrics (nests, mature abundance, immature abundance, mature sex ratio, immature sex ratio, and neritic survival equivalent [NSE]) computed from simulations better predicted each other than their respective prediction by any of the annual simulator inputs. Irrespective of maturity status, abundance fluctuated widely and inversely to age group sex ratio. The ratio of older (ages 20–29) to younger (ages 10–19) individuals provided the best lagged (21 years) prediction of annual nest counts. Our novel findings substantiate demographic metrics for monitoring, plus forecast a future annual nest count oscillation even with high survival (0.93).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Universally among taxa, age-structured abundance reflects a continuum of iterative processes across distinct life history and/or survival events. For female sea turtles, the general life history equation features nine multiplier sequences between hatching and then future nesting as an adult. The number of female hatchlings that enter the ocean annually reflects the total number of nests, the hatching and emergence success of the eggs in those nests, and sex ratio. Through age 0, the number of viable aquatic hatchlings reflects survival plus emigration from the population geographic boundaries. Most sea turtle species develop in the oceanic realm for a period of years before returning to neritic environments1; thus, annual survival may vary with age/size and/or developmental habitats. Sea turtles require up to several decades to reach sexual maturity but then rarely participate in reproductive activity annually across ensuing years.

Extrapolating generalized life history values2 for loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta [Linnaeus 1758]) reinforces that annual sea turtle hatchling abundance exceeds that of nesting females by > 50-fold. As such, lower survival rates for younger and abundant life history stages in turn dictate higher survival rates for older ages to maintain viable populations. However, over decades, reduced skewness in age-structured abundance at higher survival rates (Table 1) also supports greater resiliency to survival rate fluctuations than perhaps often appreciated. Because loggerhead sea turtles must survive for two decades between putative ages at neritic recruitment and achieving sexual maturity2, distinguishing neritic abundance trends that reflect recruitment versus survival variability remains of paramount importance. Low contemporary shrimp trawler interaction rates3 plus decades of protection from turtle excluder devices (TEDs) should minimize anthropogenic mortality. Increased survival through greater TED-compliance should also not achieve the same impact that TEDs had when first implemented4.

Following decades of conservation on beaches and in the water, annual nest counts for three sea turtle species in the Northwest Atlantic (NWA) basin now exhibit oscillation5,6,7. Later years of these data sets reveal rapidly yet only brief rebuilding from low nest counts before experiencing inter-annual oscillation. Therefore, it seems especially salient to ask, ‘how much should nest counts fluctuate following recovery?’ To answer this question, we investigated changes to a theoretical loggerhead sea turtle population scaled to resemble an important NWA nesting assemblage5. Specifically, we simulated combinations of random variability across life history parameters and cohort years (1950–2018), then characterized changes in six demographic metrics under scenarios favoring net population growth versus net population decline. Lastly, we evaluated the potential (across multiple lag intervals) of each demographic metric to predict simulated changes, with greatest emphasis on forecasting annual nest count trends.

Methods

Population simulator structure and parameterization

Annual nest count variability reflects chronic shaping of cohort abundance plus the reproductive activity of adult females from across cohorts in each nesting year. As such, four inter-related equations form a feedback loop that quantify this life history cycle7. First, nests (N) = mature females (MF) × [clutch frequency (CF) divided by remigration interval (RI)]. Second, female hatchings (FH) = N × hatchlings per nest (HpN) × proportion female (Prop F) × proportion remaining in the NWA (Prop NWA). Third, age-structured female abundance = FH x annual survival across each age, which varied broadly between age 0 (A0), oceanic survival (OS), and neritic survival (NS). Lastly, MF = the sum of projected abundance from age of sexual maturity (ASM) through oldest survivor in each year.

Cohort projection in Microsoft Excel (v2016, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, CA) began with a starting nest count of 47,433, the 30-year mean for an important nesting assemblage for loggerhead sea turtles in the NWA5. We calculated female hatchling abundance for each cohort as [N × HpN × Prop F × Prop NWA], with the integer function used to round down. Subsequent multiplication (also using the integer function) then projected female cohort abundance annually, with a shift from the OS to NS multiplier beginning in the year of neritic recruitment (NR). Annually simulating 161 possible age classes (i.e., age 0–160) prevented premature cohort disappearance in the simulator given slightly older null model maximum ages for females (105) than males (94) due to female-biased sex ratio. Annual mature females reflected survival to maturity, which for simplicity applied to all cohort survivors in the assigned maturation year. Female hatchling production produced by nest counts from mature females fed back into the simulator annually via the “iterative function” in MS Excel to link hatchlings entering and produced by the simulator.

Simulation featured only null model values (Table 2) prior to 1950, which we selected for the onset of cohort manipulation for two reasons. Biologically, even if sexual maturity occurred at age 408, manipulation of 39 cohorts prior to 1989 should have fully impacted at least one cohort prior to the first nest count reference year of5. Industrialized commercial fishing also ramped up after World War II, notably through trawling in the Gulf of Mexico9. Thus, increased variability among simulated cohorts since 1950 also served as a proxy for potentially greater cohort disruption that began around the same time as industrialized fishing.

For each life history parameter, values with the highest probability (0.114) of random selection (Table 2) resembled prior modeling for this species2, and in turn comprised the null simulator model (M0, Table 3). Alternatively, with a declining probability of random selection, twelve additional value options for each parameter (except for neritic survival) reflected a normal distribution of ± 20% variability relative to the null model values (Table 2). With null model neritic survival set at 0.93, maximum neritic survival of 0.99 could only increase by 6%.

Because Prop NWA and Age 0 survival comprise compensatory processes, Prop NWA remained static (0.9) to represent a proxy for first year proportion retention and/or survival. The null model simulator structure only generated 47,078 nests; thus, an annual correction factor added 355 nests to ensure no net increase or decrease relative to the starting null model nest count.

Model structure and associated demographic metrics

To neutrally evaluate the compounded effects of annual variability across parameters, we only simulated random changes in annual parameter values. For each parameter, random sampling from the Table 2 distribution generated 10,000 temporal trajectories (1950–2018). Next, dividing the 1950–1979 mean (i.e., first 30 years) of randomly selected values by respective Table 2 null model values generated 10,000 reference ratios per parameter. Cohort manipulation across parameters (herein referred to as models, Table 3) reflected extreme pairings of the lowest and highest reference ratios per parameter, which thus distilled 1 × 1032 model combinations to just nine (including the null) models bracketing those combinations. Models 1 and 2 altered neritic survival using the lowest and highest reference ratio trajectories, respectively. Models 3–5 (6–8) featured the lowest (highest) reference ratios for parameters other than neritic survival. Null, < 1 reference ratio, and > 1 reference ratio neritic survival, respectively, completed models 3–5 and 6–8 (Table 3). Low reference ratios spanned 0.907 (neritic recruitment age) to 0.978 (neritic survival) while high reference ratios spanned 1.023 (neritic survival) to 1.081 (hatchlings per nest). Annual parameters values simulated during 1950–2018 appear in Supplement 1.

Mixed-sex age structure compiled from separate female and male simulations across models generated several demographic metrics during 1989–20185 for analysis. Annual nest counts (N) did not differ between female and male simulations, but maximum age (Amax) did. For ease of comparison with field surveys that measure size but not maturity status, abundance groupings distinguished between ages < 30 versus ≥ 30 to approximate maturity. As such, the ratio of males to females (MM:MF) for ages ≥ 30 contextualized breeding sex ratio10 and the recent suggestion of multi-centurial mature sexual synchrony11. Conversely, per convention12, we expressed the presumed immature (age < 30) sex ratio (ISR) as the proportion of females. Lastly, neritic survival equivalent (NSE13) conveyed the abundance ratio (raised to an exponent of 1/10) of ages 20–29 versus the youngest neritic sea turtles to age 19.

Annual deviation from parameter-specific 1989–2018 means, computed as [(annual value/30-year mean)−1] standardized comparisons across models and demographic metrics. Temporal slope among annual deviations provided additional descriptive context for comparing models. Cluster analysis characterized annual deviation associations between eight metrics, eight models, and 30 observation years for each model-metric time series.

Simulator prediction and forecasting

We used correlation co-efficients to characterize associations among life history parameters and demographic metrics. Annual parameter values represented dependent inputs for six independent metrics: nests; mature female abundance; immature female abundance; male to female ratio for ages ≥ 30; proportion female among neritic ages ≤ 29; and neritic survival equivalent. A distribution of 31 correlation co-efficients compared independent and dependent series in the same year of each simulated metric (i.e., lag 0; 1989–2018) plus at 30 lag intervals where the dependent series preceded the independent series (i.e., lag 30 = 1959–1988). Metric use as both independent and dependent series further contextualized overall associative potential.

A standardized ranking system assessed the potential for dependent series to predict demographic metrics. For each predicted metric, the lowest rank indicated the highest peak correlation score, with a maximum low rank score of 2852 for the lowest peak correlation score. Rank distribution reflected 31 scores for 6 models × 8 life history parameters plus both sex ratio metrics, and 31 scores for 8 models × 4 remaining demographic metrics. Co-correlated metrics (r = 1.0) in lag year 0 did not receive ranks. As necessary, tied peak correlation scores among predictive metrics received the same rank score. Mean rank divided by peak correlation produced an index value for each of 14 dependent series per demographic metric. Lastly, dividing each index value by the sum of the respective 14 index values generated a weighted distribution for each demographic metric (and where low weight = best predictor).

We quantified a best model based on simulated nest count deviation closest to ± 0.4, the range reported in Florida during 1989–20185. After model selection, linear regression forecasted annual nest counts beyond 2018 for this model using the peak correlation input term. Increasing annual nest counts prior to 1989 for an important subset14 of the data analyzed by5 further supports model selection based on temporal deviation from the 30-year mean versus raw nest count. Multiplying annual deviations by 47,433 before linear regression then scaled annual nest counts for comparison with nest counts in Florida during 1989–20185.

Dividing the 2,852 ranks by 31 lag intervals yielded 92 absolute maximum value (i.e., peak) correlation scores for each of six demographic metrics. Among parameters, Chi-square tested for differences in the count distribution of peak correlation across lag interval bins: no lag; 1–5 years; 6–10 years; 11–15 years; 16–20 years; 21–25 years; and 26–30 years. Slope characterized temporal trends in the count of peak correlations (and maximum magnitude among replicates) across lag interval bins (with the central lag year used for multi-year bins).

We used the “correl” equation to generate correlation co-efficients in MS Excel; however, we completed formal statistical analyses (i.e., linear regression, cluster analysis, Chi-square) in Minitab (v21, Minitab Corporation, State College, PA) with significance set to α = 0.05.

Results

Population simulation and demographic metrics

Cluster analysis of annual (1989–2018) deviation distributions revealed three broad groupings. Nests and mature female abundance exhibited the greatest (95%) similarity, and the ratio of mature males to mature females joined the nest-mature female pairing with 71% similarity. Immature sex ratio completed this first broad group by joining with 57% similarity. Annual deviation in the maximum age of males and females exhibited 92% similarity across models and established the second broad grouping, which also loosely (52% similarity) featured the abundance of neritic immature females. The third broad grouping paired NSE and year with 76% similarity, followed by model with 50% similarity.

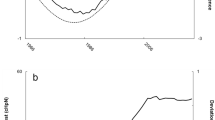

Across eight demographic metrics, nests and mature female abundance experienced the most deviation over three decades (Fig. 1a) but maximum age, irrespective of sex, exhibited the least deviation (Fig. 1b). Greatest deviation in nests, abundance, and NSE occurred with models M3-M5 (Fig. 1a), which featured reference ratios < 1 for most parameters. Conversely, models M3-M5 featured reduced deviation in sex ratio relative to models M6-M8 (Fig. 1b). Models M3-M5 also featured the greatest positive slope for deviation in nests and mature female abundance but the least slope for immature abundance and mature sex ratio (Figs. 1a, b).

Range (bars, first y-axis) and slope (line, second y-axis) for demographic metrics simulated during 1989–2018 across eight model configurations. For both panels, each x-axis label aligns with model M1 with the last data point before the next label denoting model M8. Bars denote maximum (gray) or minimum (white) deviation from each model 1989–2018 mean. Solid line conveys the 30-year slope among annual deviation values for each model and metric. Panel (a) features metrics computed for all eight models: nests; abundance of mature and immature sea turtles; and neritic survival equivalent (NSE). Dashed lines in panel (a) denote the ± 0.4 deviation in nest counts and mature females during 1989–20185. Panel (b) features metrics that remained static for models M1 and M2 due to only manipulating neritic survival: maximum age of females (F) and males (M); the ratio of mature males to females (MM:MF); and the immature sex ratio (ISR) computed as the proportion female.

Neritic survival equivalent exhibited one-fourth of the deviation of immature abundance (and minimal slope variability, Fig. 1a) despite both metrics calculated from the abundance of sea turtles ≤ age 29. Neritic survival equivalent also exhibited the least influence from model parameterization, with similar ranges for models M3-M5 (0.84–1.04) and for models M6-M8 (0.82–1.0). For models M1 and M2, which only featured variability in neritic survival, neritic survival equivalent spanned just 0.91–0.95.

Maximum age deviation reflected the parameterization of neritic survival (Fig. 1b). Maximum age did not deviate in models M3 and M6, which featured static neritic survival. Models M1, M4, and M7, all of which featured neritic survival with a reference ratio < 1, exhibited negative slope and greatest maximum age range between 1989 and 2018 (Fig. 1b). For three models (M2, M5, M8) featuring higher than null model neritic survival, corresponding abundance increases supported higher maximum ages for females (111–115) and males (99–103). Alternatively, for models with lower than null model neritic survival (M1, M3, M7), reduced abundance also lowered maximum age range to 89–97 for females and 65–86 for males.

Prediction and forecasting

Chi-square analysis detected a significant difference (χ2 = 61.963, df = 30, P< 0.001) in the distribution of peak correlation across temporal lag bins (Table 4). Dependent inputs in the year of demographic metrics represented 9% (n = 50) of peak correlations but 32% (n = 178) of dependent associations aligned more than two decades prior to demographic metrics (Table 4). Abundance of females ≥ age 30 and neritic survival equivalent exhibited the strongest positive slope for peak correlation distribution with increasing lag interval (Table 4). Conversely, the female proportion of neritic sea turtles ≤ age 29 declined the most with increasing lag interval (Table 4). Maximum correlation strength for neritic survival equivalent increased slightly with increasing lag interval; however, negative slope characterized all abundance correlation strength trends with longer lag interval (Table 4).

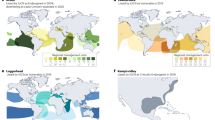

Except for the ratio of mature males to mature females, simulated metrics exhibited lower index scores than eight simulator parameter inputs for predicting these metrics (Fig. 2). Mature female abundance exhibited the lowest index scores for predicting all metrics except itself, with the lowest index score for predicting mature female abundance bestowed on immature female abundance. Among parameter inputs, oceanic survival and neritic recruitment age featured the lowest index scores with age 0 survival receiving the worst scores (Fig. 2).

Cumulative distribution of weighted predictive metric scores (bars, y-axis) among eight parameter inputs and six demographic metrics (x-axis) simulated during 1989–2018; see methods text for details regarding parameters and metrics. Predictive scores reflect correlation between input parameters or demographic metrics from 0 to 30 years prior to simulated nests (dark gray); abundance of females ≥ age 30 (light gray); abundance of neritic females ≤ age 29 (no fill); neritic survival equivalent, NSE (black); proportion female among neritic sea turtles ≤ age 29 (light pink); and male to female ratio among neritic sea turtles ≥ age 30 (dark pink).

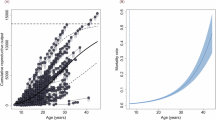

Across eight model configurations, correlation strength between mature female abundance and annual nest counts declined with increasing lag interval (Fig. 3). Alternatively, correlation strength between neritic survival equivalent and annual nest counts oscillated between strong positive and strong negative correlation peaks at approximately decadal intervals (Fig. 3).

Correlation strength distribution (y-axis) between simulated nest counts (1989–2018) versus mature females (black squares) and between simulated nests versus neritic survival equivalent (gray bars) for models M1 through M8 (x-axis). For each model, lag interval durations decrease (i.e., lag 30 to lag 0) with movement left to right along the x-axis.

Only models M6 and M7 exhibited comparable nest count range as reference data5 during 1989–2018 (Fig. 1a). Given the improbability of static neritic survival (M6) since 1950, we only further considered model M7 for nest count regression and forecasting. Normalized deviation in annual nest count for model M7 ranged from − 0.39 (2008) to 0.39 (2016), with a net deviation sum of 0. Scaling annual deviations prior to regression produced a nest count distribution (mean = 47,433) that spanned 28,660 (2008) to 65,301 (2016).

In model M7, mature female abundance in the year of nesting (i.e., lag 0) exhibited the strongest correlation with annual nest counts (r = 0.85, P < 0.001). Conversely, neritic survival equivalent 21 years prior to nesting exhibited the second-best correlation with annual nest counts for model M7 (r = − 0.78, P < 0.001). Nest association strength with neritic survival equivalent exceeded that of lagged nest count associations with prior nests, which peaked 12 years prior to nests as the third best correlation with annual nest counts in model M7 (r = − 0.72, P < 0.001).

In model M7, during the 21 years prior to 1989–2018, neritic survival equivalent spanned 0.838 (1995) to 0.999 (1986). From this 21-year lag in NSE distribution, linear regression predicted (adj. r2 = 0.59, P < 0.001) 1989–2018 annual nest counts as 191,744—(157,657 * lagged neritic survival equivalent). Hindcasting (1989–2018) fit suggested a best forecasting (2019–2039) use as a broad temporal versus precise inter-annual gauge of nest count variability (Fig. 4a).

Annual nest count panel (a) and NSE panel (b) for model 7, which across metrics most closely aligned with index nest counts from Florida during 1989–20185. For each metric, solid black lines denote simulated values and dashed black lines predict simulated values from peak NSE lag association with the simulated metric. In panel a, gray bars reflect the annual minimum and maximum nest counts reported at Florida index nesting beaches during 1989–20185.

In model M7, the neritic survival equivalent predicted itself 12 years prior given a peak correlation strength of r = − 0.90 (P < 0.001). Linear regression predicted (adj. r2 = 0.80, P < 0.001) 1989–2018 neritic survival equivalent as [1.7457—(0.9124 * lagged neritic survival equivalent)]. Like nest prediction, hindcasted fit supported greatest forecasting (2019–2030) capability as a broad gauge of temporal variability in neritic survival equivalent (Fig. 4b).

Discussion

In population modeling, several techniques enable researchers to evaluate the relative importance of life history parameter changes on population structure. Broadly, these techniques include life history matrix models15, population viability analysis2, cohort-centric simulations7,16, and individual- or agent-based modeling17,18. Sensitivity and elasticity analyses complement population models, but their findings reflect the appropriateness of matrix parameterization. Notably, a well-cited analysis for loggerhead sea turtles15 questionably modeled polymodal survival versus a more typical survival increase with age2. Polymodal survival mostly assumed shrimp trawling mortality4 given similar survival rates for oceanic juveniles (ages 1–7, 0.7857) and adults (0.8091), which also matured early (age 2215). Consequently, as parameterized15, the prior study could only deduce a need for increased neritic survival. More recently, base parameterization spurring unrealistic population growth (see Supplement 17) also concluded increased survival need for Kemp’s ridley (Lepidochelys kempii [Garman 1880]) sea turtles16. Cohort trajectories reflect compensatory multiplicative processes across parameters; thus, modelers should first ensure that simulator parameterization reflects a closed loop null model (i.e., simulated N/starting N = “1”) before proceeding with parameter manipulation. Independent of analytical approach, simulations share a common uncertainty regarding ‘real-world’ applicability given biological data limitations for model parameterization19,20.

Consistent with the adage ‘the best defense is a good offense,’ we embraced such concern as a strength and instead emphasized trends across broad lines of parameter interaction potential.

Standardizing variabiliy to ± 20% of most null model values fostered fair comparisons among parameters. Simulated annual nest count trajectories also gave equal consideration to model structures that reflected low and high reference ratio variability across parameters for 79 years. This latter observation concurs with17, whose individual-based modeling approach also featured comparable baseline oceanic (0.6445) and neritic (0.8474–0.9474) survival. Our compounded interaction effects across non-stationary parameters mirror reality and reinforce the need to simulate outcomes across dynamic cohorts versus assuming extensive stationarity with selective parameter manipulation.

Lack of ‘real-world’ vital rate data often discourages simulation, but as revealed herein, vital rates only reliably constructed cohort trajectories while poorly predicting population dynamics. This crucial finding downplays the need to discern the relative importance of the proverbial chicken versus the egg and instead shifts analytical emphasis to monitoring their shared alignment. Excluding two sex ratio metrics, peak lag association frequency increased with greater lag interval for most simulated metrics (Table 4). Abundance of females ≥ age 30 exhibited the greatest lag distribution slope, with nearly half of peak associations occurring when dependent predictors preceded abundance > 2 decades prior. This observation reinforces that contemporary abundance reflects the compounded effects of processes from the past; thus, managers must fully grasp variability frequency and magnitude. Distribution of peak association across lag intervals for nests closely resembled abundance of females ≥ age 30 but included more peak associations at lag intervals of 1–5 years (Table 4). Lag intervals ≤ 5 years reflect reproductive remigration intervals across sea turtle species21, and elevated occurrence of peak associations for nesting at shorter lag intervals may convey this. Nevertheless, comparable peak association distribution for mature female abundance and nesting at the longest lag intervals evaluated supports embracing long-term trajectory prediction of these gold standard metrics for assessing sea turtle population viability21,22.

Random generation of peak association across lag intervals for demographic monitoring metrics begs answer to the question, ‘must real-world lags reflect climate mediation?’ We randomly assigned values to characterize variation devoid of an acute cause-effect, which to date has considered both anthropogenic15,16 and climatological7,11 true climate data series.

Nevertheless, comparable variability plus temporal alignment between models M6–M7 with actual nesting data5 supports the need to consider compounded stochastic variability when evaluating climate associations on ‘real-world’ data. Given a high degree of correspondence between simulated annual abundance of females ≥ age 30 and nest counts, environmental influence on reproductive activity seems quite defensible23,24. Conversely, across demographic metrics numerous peak lag associations exceeded breeding remigration lag intervals (Table 4). Although rationalizing long lag interval associations requires more conjecture7,11,25, such complex pathways better explain extensive abundance variability as generated from random parameterization in the present study. Therefore, when evaluating climate associations, we recommend including randomized versions of the same data to contextualize correlation strength between ‘real world’ data and the true climate data series.

Contrary to the presumption that high neritic survival should bolster future nest counts, random decreases to only neritic survival produced negligible changes in annual nest counts (Fig. 1a). Random neritic survival decreases superimposed on random changes to all other parameter inputs also negligibly altered nest count distributions regardless of which direction other parameters changed relative to their null model values (Fig. 1a). Consequently, neritic survival received high index scores indicative of a poor predictor of nest counts or any of the other simulated demographic metrics (Fig. 2). Alternatively, within two model suites where all other parameters experienced random variability, increasing neritic survival further increased deviation and subsequent 30-year trajectory slopes. These findings collectively reinforce that numerous interactive processes, and not just neritic survival, shape population abundance, which then in turn limits the perceived panacea of ‘restoring’ high neritic survival. These findings, coupled with the utility of neritic survival equivalent, underscore the importance of monitoring both abundance26,27 and demographic28 trends. Given extensive deviation variability in abundance across age groups but comparably low index scores (Fig. 2) for neritic survival which featured less deviation variability, we further suggest demographic trends as most critical.

Inverse deviation trends between simulated sex ratio and abundance irrespective of sea turtle age coupled with extensive deviation in both metrics reinforces demographic resilience11. Irrespective of sea turtle age group, models with reference ratio inputs greater than null model values (i.e., M6–M8) favored greatest sex ratio deviation (Fig. 1b). Compounded deviation across multiple parameters, only one of which was cohort sex ratio, extensively shaped in-water sex ratios and underscores the fallacy of projecting future population sex ratios based solely on deviation in incubation sex ratio29,30. Across a broad diversity of parameterization, simulations generated high index values (and in turn poor predictive capability) for first year survival (Fig. 2), which further supports demographic resiliency. Low relative importance for first year survival on the ultimate abundance trajectory for each cohort also aligns with a similar conclusion previously reached through more simplistic modeling25. Among life history inputs, simulations in the present study also produced lower index scores for neritic recruitment age and oceanic survival (Fig. 2), which reinforces greater importance of these parameters relative to neritic survival as previously suggested by prior studies11,22. Most importantly, the present study clearly stated a closed-loop simulation with a null model reference ratio of “1” to avoid age structured-abundance drift in either a positive or negative direction, a vital but often overlooked first step across simulation studies22,29,30. Thus, given proper null model stability affirmation, we suggest that the present study offers the most defensible findings.

Delineation of expected trends in demographic structure across broad trajectories of underlying change represented the focus of our analyses; however, forecasting future trends for monitoring sea turtle recovery efforts also featured prevalently. Greatest overlap in annual nest counts between simulator model M7 and a 30-year reference data set5 narrowed the field of ‘how to’ scenarios to achieve the reference data set5. In contrast to prior modeling endeavors to manipulate parameters to simulate an exact reference data set7, in the present study we sought to elucidate the best metrics for population monitoring. Consequently, predicting model M7 nesting from lagged NSE only reliably produced a general trajectory trend but did not precisely forecast inter-annual variability (Fig. 4a). As such, projecting this dynamic beyond simulated nests for model M7 also represents a generalized trajectory. That said, since 2020, loggerhead sea turtle nesting in Florida only once exceeded (by 12%31) the maximum annual nest count reported during 1989–20185. This observed FL nesting for loggerhead sea turtles aligns with the model M7 extrapolation of a generalized plateau in annual nesting (Fig. 4a) and reinforces the importance of anticipating a decline in nesting over the ensuing decade.

Five decades into conservation, longer than the oldest suggested age of sexual maturity8, loggerhead sea turtles should exhibit increased probability of encounter in neritic waters32. More than ever, sea turtle monitoring must rise above ‘numerator bias’ and consider encounters in the context of population dynamics. Synchronous but out-of-phase (by roughly 7 years) ebb and flow of neritic survival equivalent and nest count association strength across lags and models (Fig. 3) substantiates expectation of population oscillation. As such, metric value increases no more reflect good outcomes than decreases reflect bad outcomes; rather, each represents alternating phases of the same cycle. Likewise, decreased (increased) neritic survival equivalent simulated under high neritic survival largely reflects shifting neritic size structure favoring a greater proportion of younger (older) cohorts. Thus, barring altered sampling methodology, high (low) catch rate years should align with greater prevalence of smaller (larger) individuals, consistent with in-water capture studies for loggerhead sea turtles in the Southeast U.S.33,34. Furthermore, temporal catch rate trends in those studies also roughly correspond with simulated (and predicted) neritic survival equivalent (Fig. 4b). At roughly 25 years between low neritic survival equivalent periods for model M7, increased shrimp trawling pressure and perception of population change4 may have accompanied higher in-water abundance in the 1970s and decreasing nest counts after the 1960s. Given minimal change in neritic abundance under reduced neritic survival across our models, we therefore recommend compiling historical data sets to compute neritic survival equivalent scores to test such correspondence.

Revisiting historical paradigms could also benefit the management of harvested species. In contrast to sea turtles, which typically generate <150 eggs per nest, harvested invertebrates35 and finfish36 exhibit fecundity rates several thousand times greater. As such, much lower parameter rates than simulated for sea turtles should support a stability ratio of “1”. For some fish stocks, abundance variability increases concurrent with harvesting37 but for other species, demographic metrics also suggest the potential for long-term cycling37,38,39. Evaluating if stock assessment parameterizations have featured (i) reasonable stability ratios coupled with (ii) emphasizing temporal trends for appropriately scaled older to younger ages would either reaffirm historical management or identify areas of divergence to investigate further. Given abbreviated or closed seasons across fisheries40, complimentary analysis that reflects size structure cycles observed by resource users may also favorably alter users’ perception of wildlife management.

Data availability

Simulator input values are provided in Supplement 1. Following acceptance and publication, the datasets generated and analyzed for the present study will become available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bolten, A. B. Variation in sea turtle life history patterns: neritic vs. oceanic developmental stages. In The Biology of Sea Turtles (eds Bolten, A. B., Lutz, P. L., Musick, J. A., & Wyneken, J.), 243–257 Vol. 2 (CRC Press, 2003).

Conant, T. A., et al. Loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) 2009 status review under the US Endangered Species Act. In Report of the Loggerhead Biological Review TEAM to the National Marine Fisheries Service, 222 (2009).

Babcock, E. A., M. Barnette, J. Bohnsack, J. J. Isely, C. Porch, et al. Integrated Bayesian models to estimate bycatch of sea turtles in the Gulf of Mexico and southeastern U.S. Atlantic coast shrimp otter trawl fishery. NOAA Tech Memorandum NMFS-SEFSC-721, 47 (2011).

National Research Council. Decline of the sea turtles: causes and prevention. (National Academies Press, 1990).

Ceriani, S. A., Casale, P., Brost, M., Leone, E. H. & Witherington, B. E. Conservation implications of sea turtle nesting trends: elusive recovery of a globally important loggerhead population. Ecosphere 10, e02936 (2019).

del Monte-Luna, P. et al. Multidecadal fluctuations in green turtle hatchling production related to climate variability. Sci. Rep. 13, 1542 (2023).

Arendt, M. D., Schwenter, J. A. & Owens, D. W. Climate-mediated population dynamics for the world’s most endangered sea turtle species. Sci. Rep. 13, 14444 (2023).

Scott, R., Marsh, R. & Hays, G. C. Life in the really slow lane: loggerhead sea turtles mature late relative to other reptiles. Funct. Ecol. 26, 227–235 (2012).

Condrey, R. & D. Fuller. The U.S. Gulf Shrimp Fishery in Climate variability, climate change and fisheries (ed. Glantz, M. H.) 89–119 (Cambridge University Press, 1992).

Lasala, J. A., Hughes, C. R. & Wyneken, J. Breeding sex ratio and population size of loggerhead turtles from Southwestern Florida. PLoS ONE 13, e0191615 (2018).

Arendt, M. D., Schwenter, J. A., Owens, W. D. & Valverde, R. A. Theoretical modeling and neritic monitoring of loggerhead Caretta caretta [Linnaeus, 1758] sea turtle sex ratio in the southeast United States do not substantiate fears of a male-limited population. Global Change Biol. 27, 4849–4859 (2021).

Mrosovsky, N. Sex ratios of sea turtles. J. Exp. Zool. 270, 16–27 (1994).

Arendt, M. D., Webster, R. P. & Schwenter, J. A. High annual survival suggested by size structure of Kemp’s ridley sea turtles captured by coastal research trawling in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean since 1990. Endang. Species Res. 48, 107–121 (2022).

Ehrhart, L., Redfoot, W., Bagley, D. & Mansfield, K. Long-term trends in loggerhead (Caretta caretta) nesting and reproductive success at an important western Atlantic rookery. Chel. Conserv. Biol. 13, 173–181 (2014).

Crouse, D. T., Crowder, L. B. & Caswell, H. A stage-based population model for loggerhead sea turtles and implications for conservation. Ecol. 68, 1412–1423 (1987).

Gallaway, B. J. et al. Development of Kemp’s ridley sea turtle stock assessment model. Gulf Mex. Sci. 33, 138–157 (2016).

Mazaris, A. D., Fiksen, Ø. & Matsinos, Y. G. Using an individual-based model for assessment of sea turtle population viability. Pop. Ecol. 47, 179–191 (2005).

Piacenza, S. E., Richards, P. M. & Heppell, S. S. An agent-based model to evaluate recovery times and monitoring strategies to increase accuracy of sea turtle population assessments. Ecol. Model. 358, 25–39 (2017).

Boyce, M. S. Population viability analysis. An. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 23, 481–506 (1992).

Reed, J. M. et al. Emerging issues in population viability analysis. Conserv. Biol. 16, 7–19 (2002).

Casale, P. & Ceriani, S. A. Sea turtle populations are overestimated worldwide from remigration intervals: Correction for bias. Endang. Spec. Res. 41, 141–151 (2020).

Mazaris, A. D., Schofield, G., Gkazinou, C. A., Almpanidou, V. & Hays, G. C. Global sea turtle conservation successes. Sci. Adv. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1600730 (2017).

Chaloupka, M., Kamezaki, N. & Limpus, C. Is climate change affecting the population dynamics of the endangered Pacific loggerhead sea turtle?. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 356, 136–143 (2008).

Neeman, N., Spotila, J. R. & O’Connor, M. P. A simple, physiologically-based model of sea turtle remigration intervals and nesting population dynamics: Effects of temperature. J. Theor. Biol. 380, 516–523 (2015).

Arendt, M. D., Schwenter, J. A., Witherington, B. E., Meylan, A. B. & Saba, V. S. Historical versus contemporary climate forcing on the annual nesting variability of loggerhead sea turtles in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean. PLoS ONE 8, e81097 (2013).

Schroeder, B., et al. Developing and evaluating methods to determine abundance and trends of Northwest Atlantic loggerhead turtles. NOAA Tech Memo NMFS-OPR-67 (2020).

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration & Department of the Interior. A Comprehensive Plan for In-water Sea Turtle Data Collection in the US Gulf of Mexico, 69 (2023), accessed 9 July 2024; https://content-drupal-gulfspill.woc.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/In-Water%20Sea%20Turtle%20Plan_FINAL.pdf

Board, Ocean Studies, and National Research Council. Assessment of sea-turtle status and trends: integrating demography and abundance, 1–162 (National Academies Press, 2010).

Heppell, S. S., Wyneken, J. & Heppell, S. A. A morphologist, a modeller, and an endocrinologist consider sea turtle sex ratios in a changing climate. Some wine was involved. Front. Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.952432 (2022).

Catron, S. et al. Modeling the impacts of temperature during nesting seasons on loggerhead (Caretta caretta) sea turtle populations in south Florida. Ecol. Model. 481, 110363 (2023).

FWC Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, Statewide Nesting Beach Survey Program. Loggerhead nesting data, 2020–2024, accessed 26 June 2025; https://myfwc.com/media/zynbnzs3/loggerheadnestingdata5years.pdf

Putman, N. F., Hawkins, J. & Gallaway, B. J. Managing fisheries in a world with more sea turtles. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lon. B. 287, 20200220 (2020).

Ehrhart, L. M., Redfoot, W. E. & Bagley, D. A. Marine turtles of the central region of the Indian River Lagoon System. Florida. Fla. Sci. 70, 415–434 (2007).

Arendt, M. D. et al. Temporal trends (2000–2011) and influences on fishery-independent catch rates for loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) at an important coastal foraging region in the southeastern United States. Fish. Bull. 110, 470–483 (2012).

Prager, M. H., McConaugha, J. R., Jones, C. M. & Geer, P. J. Fecundity of blue crab, Callinectes sapidus, in Chesapeake Bay: Biological, statistical and management considerations. Bull. Mar. Sci. 46, 170–179 (1990).

Harris, P. J., Wyanski, D. M., White, D. B. & Moore, J. L. Age, growth, and reproduction of scamp, Mycteroperca phenax, in the southwestern North Atlantic, 1979–1997. Bull. Mar. Sci. 70, 113–132 (2002).

Anderson, C. N. K. et al. Why fishing magnifies fluctuations in fish abundance. Nature 452, 835–839 (2008).

Bacheler, N. M. & Ballenger, J. C. Spatial and temporal patterns of black sea bass sizes and catches in the Southeastern United States inferred from spatially explicit nonlinear models. Mar. Coast. Fish. 7, 523–536 (2015).

Bacheler, N. M. & Ballenger, J. C. Decadal-scale decline of scamp (Mycteroperca phenax) abundance along the southeast United States Atlantic coast. Fish. Res. 204, 74–87 (2018).

Federal fishing regulations. South Atlantic Fisheries Management Council (2024). Available online, accessed 9 July 2024; https://safmc.net/regulations/

Acknowledgements

A strong desire to convey the importance of lag effects and the need to substantiate root causes for oscillations across data sets motivated completion of this manuscript. Funding provided by NOAA (NA21NMF4720491) supported this journey. We thank T. Smart, P. Marcum and E. Weeks (SCDNR) plus D.W. Owens (CofC, ret.) and journal reviewers for editorial assistance. This publication represents SCDNR contribution number (900).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MDA conceived the study design, completed all analyses, and compiled the manuscript. JAS served as the analytical and editorial ‘co-pilot’ throughout manuscript development.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arendt, M.D., Schwenter, J.A. Simulating population dynamics of sea turtles in a high survival world. Sci Rep 15, 26965 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10482-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10482-4