Abstract

Leishmaniasis is one of the infectious diseases caused by protozoa and is considered the second most significant parasitic disease after malaria. In this research, thiosemicarbazone Schiff base derivatives were synthesized via a one-pot, two-step, three-component reaction. Then, the effectiveness of the compounds against the two forms of Leishmania major and Leishmania tropica called amastigote and promastigote, was tested. All synthesized compounds displayed weak to good anti-amastigote and anti-promastigote activities. Notably, compounds 5g and 5p were the most potent compounds against amastigote and promastigote forms, respectively, of Leishmania major, with IC50 = 26.7 µM and 12.77 µM. Analogues 5e and 5g were the most potent compounds against amastigote and promastigote forms of Leishmania tropica, with IC50 = 92.3 µM and 12.77 µM, respectively. The cytotoxicity activity of the compounds was also evaluated using the J774.A1 cell lines. Some of the screened derivatives displayed low cytotoxicity to macrophage infection. Among compounds, 5p and 5e showed the highest SI (95.4 and 34.6) against L. major and L. tropica, respectively. In the next phase, the most effective thiosemicarbazone derivatives were examined for their ability to induce apoptosis in promastigotes. According to the results, these compounds displayed different early and late apoptosis as well as necrotic effects on promastigotes of Leishmania major and Leishmania tropica. Furthermore, the compounds’ drug-likeness and pharmacokinetic parameters were predicted in silico. All compounds showed acceptable drug-likeness and pharmacokinetic profiles. Furthermore, the most likely sites of the compounds metabolized by the major cytochromes were identified. Additionally, the in silico compounds’ cardiotoxicity potential was assessed. This investigation showed compounds 5m-p were cardiotoxic. Lastly, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations were performed to explore the potential mechanisms of anti-leishmanial activity in the LmPRT1 active site.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infectious diseases have been a fundamental aspect of human health illnesses since ancient times. Bacteria, fungi, viruses, protozoa, parasites, and other pathogens are responsible for these infections1. Some of these pathogens cause life-threatening diseases, whereas others have relatively minor impact on human health. A broad spectrum of pathogens—including protozoa, viruses, bacteria, and helminths—are responsible for the neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), which primarily affect populations in tropical and subtropical regions. With more than one billion people affected worldwide—particularly in underprivileged areas of Africa, Asia, and Latin America—these diseases represent a critical concern for global public health2. Leishmaniasis is one of the infectious diseases caused by protozoa and is considered the second most significant parasitic disease after malaria3. Skin ulcers, skin sores, stuffy nose/lips/gums, and nose bleeding are typical symptoms of this disease4. The impoverished, malnourished people, migrants, and those with weakened immune systems are particularly vulnerable. Environmental factors such as deforestation, climate change, dam construction, and water projects also contribute significantly to the spread of leishmaniasis5. This disease is present in over 98 countries, infecting more than 13 million people and causing an average of 300,000 cases every year. Leishmaniasis threatens around 1.7 billion individuals in endemic regions. Clinical manifestations are categorized into three types: mucocutaneous, cutaneous, and visceral6. Leishmania is transmitted by the bite of an infected female Phlebotomine sandfly, after which the protozoan invades the spleen, liver, and bone marrow via macrophages7. Leishmania’s life cycle is dimorphic, with parasites living as external promastigotes in vectors and intracellular amastigotes in mammalian host macrophages8. The genome of Leishmania major (L. major) was the first to be sequenced, laying the groundwork for subsequent genomic studies in the Leishmania genus. Cutaneous leishmaniasis, most commonly caused by L. major, usually heals on its own in humans but often leads to cosmetically disfiguring scarring9.

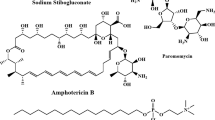

In January 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) unveiled its 2021–2030 roadmap in Geneva, outlining a comprehensive strategy to combat 20 NTDs. Among its primary objectives is the control and eventual elimination of leishmaniasis10. The current treatment of leishmaniasis relies on a limited selection of drugs, administered either monotherapy or in combination, depending on factors such as the disease type, the causative species, the geographic distribution, and the patient condition9. Drug discovery for NTDs faces numerous challenges. Economically, the low income of affected populations leads to minimal expected return on investment, discouraging pharmaceutical development. Biologically, the intricate and often poorly understood life cycles of the parasites pose significant obstacles. Chemically, new compounds must meet strict criteria, including low cost, ease of handling, chemical stability, low toxicity, and favorable pharmacokinetics—all of which are difficult to predict in the early stages. In addition, resistance development must be avoided. Pharmacologically, therapies must be suitable for diverse patient populations, including individuals with varying ages and comorbidities. These multifaceted challenges contribute to the already high attrition rates in drug development pipelines, and leishmaniasis is no exception to this pattern11. The main target of anti-leishmanial drugs is Leishmania amastigotes that live in macrophage phagolysosomes; however, this is not an easy target because drugs must overwhelm key structural barriers12. Although several treatment options exist for leishmaniasis, therapeutic management remains challenging due to the disease’s clinical diversity and complexity. Current anti-leishmanial therapies are far from optimal, primarily because of their considerable toxicity, limited efficacy, parenteral administration—which reduces patient compliance—high treatment costs, emerging drug resistance, and poor accessibility in endemic regions. Moreover, the effectiveness of certain compounds varies significantly depending on the Leishmania species, the clinical manifestation, and the geographic origin of the infection13. The continued rise in resistance to existing anti-leishmanial agents highlights the need to reassess the widespread reliance on monotherapies. Combination therapy offers a promising strategy to address these challenges. It is designed to delay or prevent the development of resistance, enhance therapeutic efficacy through synergistic mechanisms, allow for lower individual drug dosages, and shorten treatment duration—thereby minimizing overall toxicity. An important consideration in combination regimens is the pharmacokinetic profile of the drugs, particularly their half-lives. The ideal approach involves pairing a highly potent short-acting compound with a longer-acting partner to ensure sustained parasite clearance. Additionally, factors such as tissue distribution, volume of distribution, and macrophage uptake are crucial in determining therapeutic success—especially against intracellular Leishmania amastigotes residing in organs of the reticuloendothelial system13. The FDA-approved drugs for leishmaniasis are illustrated in Fig. 1. Leishmaniasis poses a mammoth task in the field of drug discovery due to the outrageous limitations associated with clinically available anti-leishmanial drugs, namely stibogluconate (Pentostam®), meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime®), ketoconazole, liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome®), miltefosine, and paromomycin. Long-term use in highly endemic regions has contributed to growing drug resistance. Due to the limited effectiveness of available chemotherapeutics, the absence of vaccines, and the lack of novel agents, there is an urgent need to develop safe, affordable, and short-course treatments with novel mechanisms of action14,15. As a result, there is a crucial need to produce more effective and safer drugs that may function through other pathways than previously described treatments. In this regard, research efforts by scientists around the world resulted in the discovery and development of some new anti-leishmanial drugs, some of which are currently in numerous stages of clinical trials. Anti-leishmanial drugs under clinical development include GSK3186899, DNDI-0690, 18-methoxy coronaridine, meglumine, and pentoxifylline (Fig. 1)5.

Thiosemicarbazones are simply generated through the condensation of a thiosemicarbazide with ketones and/or aldehydes. With the general formula R1R2CH = N-NH-(C = S)-NH2, thiosemicarbazones have captured maximum attention for their multifunctional coordination modes to transition metal ions and a huge spectrum of biological activities16particularly their leishmanicidal action. The medical application of thiosemicarbazones dates back to the 1950s, when their biological activity against tuberculosis and leprosy was first reported. Their therapeutic efficacy is influenced by various factors, such as the electronic configuration of the coordinated metal ions, the nature and position of substituent groups, and the number of available donor atoms involved in coordination16. Methisazone is an FDA-approved drug that inhibits protein synthesis and mRNA, particularly in pox viruses17. Thioacetazone is an oral antibiotic that is used in the treatment of tuberculosis. Also, triapine (3-AP) is a potent inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase (Fig. 2)18. Amithiozone has been applied in trials studying the treatment of mycobacterium avium-intracellulare infection. Perchlozone is a thiosemicarbazone used for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Perchlozone is a prodrug that is activated by ethA and inhibits the HadABC complex (Fig. 2). Thiosemicarbazone analogues have demonstrated efficiency against leishmania amastigotes and promastigotes, with likely mechanisms of action elucidated, including mitochondrial depolarization, DNA interaction, parasite death via apoptosis, and parasite protein inhibition15,19. The thiosemicarbazone scaffold was previously identified in the arena of anti-parasitic compounds. Thiosemicarbazones were first developed as parasitic cysteine protease inhibitors, like rhodhesain in T. brucei and cruzain in T. cruzi, two enzymes that play critical roles throughout the parasite’s life cycle. Some members of this group of derivatives were inactive on the enzyme but active on parasites, implying that cruzain was not the main target for some of these derivatives. Thiosemicarbazone metal-complexes or their formation of strong metal chelates recommend that the mechanism of action is mostly because of a dual pathway, including the production of metal complex-DNA interaction or toxic free radicals by thiosemicarbazone bio-reduction20.

Multi-component reactions (MCRs) represent a valuable synthetic strategy in both organic and medicinal chemistry. They have been widely utilized in diverse synthetic applications where conventional methods often require multiple steps and labor-intensive procedures. MCRs offer numerous advantages, including high product yields, atom and step economy, shorter reaction times, and environmental friendliness. Moreover, they serve as powerful tools for rapidly generating libraries of new chemical entities (NCEs), particularly valuable in the drug discovery process. Significant advancements have been made in the development and application of MCRs through extensive research. Among the three main types of one-pot synthetic methodologies—(1) cascade reactions, (2) multicomponent reactions (MCRs), and (3) one-pot stepwise synthesis (OPSS)—the OPSS approach is considered more adaptable and practical. This is largely due to its stepwise execution, which allows for modification of reaction conditions at each stage to optimize the overall synthetic process21. Under basic conditions, MCRs can generate both carbon-heteroatom and carbon-carbon bonds22,23,24,25.

In the present study, a series of derivatives with a thiosemicarbazone scaffold have been synthesized via a one-pot, two-step, three-component approach and evaluated against promastigote and amastigote forms of L. major and L. tropica. Finally, in silico insights regarding compounds for future study and stability were obtained.

Materials and methods

Synthesis

All chemicals were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company and were used without further purification. Melting points were measured using an Electrothermal 9100 apparatus and were uncorrected. FT-IR spectra were recorded using a Shimadzu 8400 S spectrophotometer. The NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker AVANCE DMX400 spectrometer, operating at 100 MHz13C-NMR) and 400 MHz1H-NMR), with DMSO as the solvent and TMS as an internal standard.

General process for the synthesis of 2-aryl-N-alkylhydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5a-p)

The mixture of hydrazine (1 mmol) and substituted isothiocyanate (1 mmol) was heated in ethanol (20 mL) in the presence of a Et3N as catalyst. After precipitate formation, aromatic aldehyde (1 mmol), sodium sulfate, and acetic acid (1 drop) were added to the mixture, which was then refluxed. The progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC. Upon completion, the mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature and then placed in an ice bath. The synthesized solid was filtered, washed with water, and re-crystallized from water/ethanol (1:1) to obtain the desired pure products.

2-(3,4-Dimethoxybenzylidene)-N-methylhydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5a)26

Yellow solid; Yield 80%; m.p. 194–195 ºC; Rf = 0.52 (n-hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1.2); FT-IR (KBr, υ) cm− 1: 3353, 3152, 3005, 2896, 1603, 1549, 1402, 1271, 1237, 1085, 1018, 639;1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 11.40 (1 H, s, NH), 8.43 (1 H, d, J = 4.8 Hz, CH), 7.98 (1 H, s, Ph), 7.46 (1 H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, NH), 7.20 (1 H, dd, J1 = 1.6 Hz, J2 = 2.0 Hz, Ph), 6.98 (1 H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, Ph), 3.83 (3 H, s, OCH3), 3.79 (3 H, s, OCH3), 3.04 (3 H, d, J = 4.8 Hz, CH3);13C-NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 177.5, 150.2, 148.7, 141.9, 126.6, 121.5, 111.3, 108.6, 55.7, 55.6, 30.4; MS (m/z, %): 253.10 (M), 223.20 (67), 179.11 (52), 164.21 (100); Anal. Calcd for C11H15N3O2S: C, 52.15; H, 5.97; N, 16.59; S, 12.66%. Found: C, 51.76; H, 5.76; N, 16.76; S, 12.51%.

2-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxybenzylidene)-N-methylhydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5b)27

Yellowish solid; Yield 83%; m.p. 145–146 ºC; Rf = 0.62 (n-hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1.2); FT-IR (KBr, υ) cm− 1: 3358, 3142, 3002, 1617, 1560, 1400, 1283, 1217, 1158, 1086, 617;1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 11.32 (1 H, s, NH), 8.57 (1 H, s, CH), 8.38 (1 H, d, J = 4.4 Hz, Ph), 7.94 (1 H, s, NH), 7.43 (1 H, dd, J1 = 2.0 Hz, J2 = 2.0 Hz, Ph), 7.10 (1 H, dd, J1 = 1.6 Hz, J2 = 2.0 Hz, Ph), 6.79 (1 H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, OH), 3.83 (3 H, s, OCH3), 3.04 (3 H, s, CH3);13C-NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 177.5, 148.7, 147.6, 143.1, 125.5, 121.5, 114.9, 109.8, 55.2, 30.4; MS (m/z, %): 239.09 (M), 224.10 (48), 196.10 (35), 151.20 (100), 137.2 (64); Anal. Calcd for C10H13N3O2S: C, 50.19; H, 5.48; N, 17.56; S, 13.40%. Found: C, 50.53; H, 5.33; N, 17.37; S, 13.65%.

N-Methyl-2-(4-methylbenzylidene)hydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5c)28,29

White solid; Yield 82%; m.p. 161–162 ºC; Rf = 0.79 (n-hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1.2); FT-IR (KBr, υ) cm− 1: 3325, 3156, 3009, 1613, 1545, 1401, 1258, 1170, 1089, 1032, 630;1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 11.43 (1 H, s, NH), 8.48 (1 H, d, J = 4.8 Hz, CH), 8.02 (1 H, s, NH), 7.69 (2 H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, Ph), 7.23 (2 H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, Ph), 3.02 (3 H, d, J = 4.4 Hz, CH3), 2.33 (3 H, s, CH3);13C-NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 177.9, 141.6, 139.1, 131.3, 128.9, 126.7, 30.5, 20.8; MS (m/z, %): 209.15 (M), 194.15 (100), 179.12 (44), 119.01 (48), 91.11 (80); Anal. Calcd for C10H13N3S: C, 57.94; H, 6.32; N, 20.27; S, 15.47%. Found: C, 57.57; H, 6.08; N, 20.46; S, 15.73%.

2-(4-Fluorobenzylidene)-N-methylhydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5d)28

White solid; Yield 92%; m.p. 184–186 ºC; Rf = 0.80 (n-hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1.2); FT-IR (KBr, υ) cm− 1: 3318, 3156, 3007, 1601, 1543, 1401, 1233, 1256, 1086, 1033, 628;1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 11.50 (1 H, s, NH), 8.55 (1 H, d, J = 4.4 Hz, CH), 8.03 (1 H, s, NH), 7.87 (2 H, dd, J1 = 5.6 Hz, J2 = 5.6 Hz, Ph), 7.25 (2 H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, Ph), 3.02 (3 H, s, CH3);13C-NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 177.9, 163.8, 161.5, 140.3, 129.4, 115.5, 31.8; MS (m/z, %): 211.15 (M), 196.15 (32), 180.20 (100), 139.20 (30); Anal. Calcd for C9H10FN3S: C, 51.17; H, 4.77; N, 19.89; S, 15.18%. Found: C, 51.55; H, 6.08; N, 20.46; S, 15.73%.

2-(4-Bromobenzylidene)-N-methylhydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5e)30

White solid.; Yield 81%; m.p. 210–211 ºC; Rf = 0.88 (n-hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1.2); FT-IR (KBr, υ) cm− 1: 3341, 3154, 3006, 2882, 1588, 1542, 1482, 1397, 1266, 1161, 1087, 1032, 622;1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 11.55 (1 H, s, NH), 8.58 (1 H, d, J = 4.4 Hz, CH), 8.01 (1 H, s, NH), 7.77 (2 H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, Ph), 7.61 (2 H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, Ph), 3.02 (3 H, d, J = 4.4 Hz, CH3);13C-NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 177.5, 140.2, 133.6, 131.5, 128.8, 122.4, 30.7; MS (m/z, %): 273 [M + 2], 271 [M], 199 (35), 120 (40), 88 (100); Anal. Calcd for C9H10BrN3S: C, 39.72; H, 3.70; N, 15.44; S, 11.78%. Found: C, 40.03; H, 3.99; N, 15.23; S, 11.60%.

2-(4-Nitrobenzylidene)-N-methylhydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5f)31,32

Yellow solid.; Yield 77%; m.p. 247–249 ºC; Rf = 0.80 (n-hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1.2); FT-IR (KBr, υ) cm− 1: 3374, 3144, 3005, 1608, 1511, 1400, 1340, 1252, 1096, 1043, 624;1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 11.79 (1 H, s, NH), 8.77 (1 H, d, J = 4.4 Hz, CH), 8.25 (2 H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, Ph), 8.13 (1 H, s, NH), 8.09 (2 H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, Ph), 3.04 (3 H, d, J = 4.8 Hz, CH3);13C-NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 176.8, 151.1, 142.3, 128.2, 121.4, 111.3, 30.5; MS (m/z, %): 238.20 [M], 207.21 (41), 152.20 (100), 120.25 (72), 91.20 (40); Anal. Calcd for C9H10N4O2S: C, 45.37; H, 4.23; N, 23.51; S, 13.46%. Found: C, 45.04; H, 4.35; N, 22.99; S, 13.63%.

N-Methyl-2-(4-methoxybenzylidene)hydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5g)28

Yellow solid.; Yield 83%; m.p. 192–193 ºC; Rf = 0.75 (n-hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1.2); FT-IR (KBr, υ) cm− 1: 3320, 3158, 3010, 2987, 1602, 1509, 1401, 1254, 1166, 1083, 1033, 632;1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 11.50 (1 H, s, NH), 8.55 (1 H, s, CH), 8.04 (1 H, d, J = 2.8 Hz, NH), 7.89–7.87 (2 H, m, Ph), 7.29–7.24 (2 H, m, Ph), 3.84 (3 H, s, OCH3), 3.02 (3 H, d, J = 2.8 Hz, CH3);13C-NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 177.8, 147.1, 140.8, 138.9, 127.7, 123.5, 53.9, 30.5; MS (m/z, %): 239.20 [M], 208.10 (45), 196.10 (67), 91.20 (100); Anal. Calcd for C9H13N3OS: C, 53.79; H, 5.87; N, 18.82; S, 14.36%. Found: C, 53.45; H, 6.15; N, 18.71; S, 14.55%.

N-Methyl-2-(4-N, N-dimethylbenzylidene)hydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5h)33

Green solid.; Yield 70%; m.p. 240–241 ºC; Rf = 0.78 (n-hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1.2); FT-IR (KBr, υ) cm− 1: 3328, 3147, 2996, 2871, 1594, 1521, 1408, 1266, 1172, 1080, 1036, 618;1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 11.22 (1 H, s, NH), 8.30 (1 H, d, J = 4.4 Hz, CH), 7.93 (1 H, s, NH), 7.59 (2 H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, Ph), 6.71 (2 H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, Ph), 3.01 (3 H, d, J = 4.8 Hz, CH3), 2.97 (6 H, s, 2 × CH3);13C-NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 177.2, 151.3, 142.5, 128.5, 121.1, 110.9, 42.6, 30.4; MS (m/z, %): 224.20 [M], 193.10 (48), 180.20 (36), 120.05 (30), 91.15 (100), 60.10 (40); Anal. Calcd for C11H16N4S: C, 55.90; H, 6.82; N, 23.71; S, 13.57%. Found: C, 55.59; H, 6.66; N, 23.99; S, 13.86%.

2-(4-Fluorobenzylidene)-N-nitrohydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5i)

White solid.; Yield 80%; m.p. 158–159 ºC; Rf = 0.25 (n-hexane/ethyl acetate 2:0.5); FT-IR (KBr, υ) cm− 1: 3318, 3157, 3003, 2984, 1600, 1506, 1403, 1234, 1066, 633;1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 11.55 (1 H, s, NH), 8.60 (1 H, d, J = 4.4 Hz, CH), 8.09 (1 H, s, NH), 7.92 (2 H, dd, J1 = 5.6 Hz, J2 = 5.6 Hz, Ph), 7.32 (2 H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, Ph);13C-NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 175.3, 143.4, 136.7, 134.5, 131.8, 125.4; MS (m/z, %): 242.10 [M], 196.03 (59), 182.10 (62), 137.16 (100), 119.04 (46); Anal. Calcd for C8H7FN4O2S: C, 39.67; H, 2.91; N, 23.13; S, 13.24%. Found: C, 40.04; H, 3.05; N, 22.88; S, 13.14%.

2-(4-Bromobenzylidene)-N-nitrohydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5j)

White solid.; Yield 82%; m.p. 200–201 ºC; Rf = 0.25 (n-hexane/ethyl acetate 2:0.6); FT-IR (KBr, υ) cm− 1: 3341, 3154, 3005, 2968, 1585, 1542, 1481, 1266, 1162, 1064, 1032, 622;1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 11.60 (1 H, s, NH), 8.63 (1 H, d, J = 4.4 Hz, CH), 8.06 (1 H, s, NH), 7.82 (2 H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, Ph), 7.66 (2 H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, Ph);13C-NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 177.8, 140.2, 133.1, 131.5, 128.6, 122.4; MS (m/z, %): 305.15 [M + 2], 303.07 [M], 271.10 (95), 199.01 (35), 120.15 (48), 88.05 (100); Anal. Calcd for C8H7BrN4O2S: C, 31.70; H, 2.33; N, 18.48; S, 10.58%. Found: C, 32.04; H, 2.50; N, 18.22; S, 10.45%.

2-(3,4-Dimethoxybenzylidene)-N-nitrohydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5k)

White solid; Yield 91%; m.p. 198–199 ºC; Rf = 0.37 (n-hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1.5); FT-IR (KBr, υ) cm− 1: 3353, 3151, 3004, 2971, 1602, 1549, 1401, 1270, 1237, 1085, 1018, 639;1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 11.40 (1 H, s, NH), 8.43 (1 H, J = 4.4 Hz, CH), 7.98 (1 H, s, NH), 7.46 (1 H, d, J = 1.6 Hz, Ph), 7.20 (1 H, dd, J1 = 2.0 Hz, J2 = 1.6 Hz, Ph), 6.98 (1 H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, Ph), 3.83 (3 H, s, OCH3), 3.79 (3 H, s, OCH3);13C-NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 177.4, 150.3, 148.8, 141.6, 126.5, 121.4, 111.1, 108.3, 55.3, 55.2; MS (m/z, %): 284.15 [M], 255.17 (100), 221.10 (37), 179.18 (65), 119.15 (45); Anal. Calcd for C10H12N4O4S: C, 42.25; H, 4.25; N, 19.71; S, 11.28%. Found: C, 42.62; H, 4.12; N, 19.96; S, 11.16%.

2-(4-Methylbenzylidene)-N-nitrohydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5l)

White solid.; Yield 88%; m.p. 188–189 ºC; Rf = 0.35 (n-hexane/ethyl acetate 2:1.5); FT-IR (KBr, υ) cm− 1: 3325, 3157, 3006, 2987, 1605, 1545, 1402, 1256, 1174, 1088, 1032, 629;1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 11.44 (1 H, s, NH), 8.48 (1 H, d, J = 4.8 Hz, CH), 8.02 (1 H, s, NH), 7.69 (2 H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, Ph), 7.23 (2 H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, Ph), 3.02 (3 H, d, J = 4.4 Hz, CH3);13C-NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 177.8, 142.6, 138.5, 132.7, 128.2, 126.5, 30.7; MS (m/z, %): 338.10 [M], 192.10 (54), 133.12 (100), 119.15 (67); Anal. Calcd for C9H10N4O2S: C, 45.37; H, 4.23; N, 23.51; S, 13.46%. Found: C, 45.05; H, 4.13; N, 23.23; S, 11.72%.

2-(4-Methoxybenzylidene)-N-(pyridin-3-yl)hydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5m)

White solid.; Yield 85%; m.p. 154–155 ºC; Rf = 0.62 (n-hexane/ethyl acetate 1:1.5); FT-IR (KBr, υ) cm− 1: 3395, 3159, 3008, 2975, 1588, 1533, 1401, 1215, 1182, 1048, 1029, 630;1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 11.98 (1 H, s, NH), 10.09 (1 H, s, br, CH), 8.74 (1 H, s, NH), 8.40 (2 H, d, J = 4.0 Hz, Ph), 8.05 (3 H, brs, Ph), 7.46 (3 H, dd, J1 = 4.8 Hz, J2 = 4.8 Hz, Ph), 3.42 (3 H, brs, OCH3);13C-NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 177.8, 146.5, 144.7, 141.8, 139.7, 137.6, 128.1, 123.4, 115.2, 111.3, 111.1, 48.2; MS (m/z, %): 285.05 [M] (100), 271.15 (38), 185.15 (68), 153.05 (71), 89.14 (15); Anal. Calcd for C14H14N4OS: C, 58.72; H, 4.93; N, 19.57; S, 11.20%. Found: C, 58.42; H, 5.02; N, 19.36; S, 11.37%.

2-(4-Bromobenzylidene)-N-(pyridin-3-yl)hydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5n)

White solid.; Yield 80%; m.p. 157–158 ºC; Rf = 0.75 (n-hexane/ethyl acetate 1:0.25); FT-IR (KBr, υ) cm− 1: 3416, 3134, 3005, 2991, 1633, 1502, 1400, 1212, 1180, 1083, 1025, 630;1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 11.86 (1 H, s, NH), 9.85 (1 H, s, CH), 8.28 (1 H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, NH), 8.21 (1 H, dd, J1 = 1.2 Hz, J2 = 1.2 Hz, Ph), 7.77 (1 H, s, Ph), 7.62–7.56 (3 H, m, Ph), 7.03 (1 H, dd, J1 = 4.8 Hz, J2 = 4.8 Hz, Ph), 6.87 (2 H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, Ph);13C-NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 192.2, 168.9, 141.8, 141.5, 138.1, 135.5, 132.1, 131.4, 130.5, 123.2, 122.6; MS (m/z, %): 337.05 [M + 2], 335.17 [M], 273.10 (98), 271.10 (95), 199.05 (45), 120.10 (52), 88.18 (100); Anal. Calcd for C13H11BrN4S: C, 46.58; H, 3.31; N, 16.71; S, 9.57%. Found: C, 46.22; H, 3.19; N, 16.45; S, 9.38%.

2-(3,4-Dimethoxybenzylidene)-N-(pyridin-3-yl)hydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5o)

Light yellow solid.; Yield 91%; m.p. 175–176 ºC; Rf = 0.25 (n-hexane/ethyl acetate 1:2); FT-IR (KBr, υ) cm− 1: 3337, 3136, 2996, 1600, 1510, 1400, 1222, 1143, 1024, 625;1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 11.87 (1 H, s, NH), 10.07 (1 H, s, CH), 8.61–8.63 (1 H, m, NH), 8.33–8.34 (1 H, m, Ph), 8.04–8.11 (1 H, m, Ph), 7.92–7.94 (1 H, m, Ph), 7.49 (1 H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, Ph), 7.28–7.37 (1 H, m, Ph), 7.23 (1 H, dd, J1 = 1.6, J2 = 1.6 Hz, Ph), 6.93 (1 H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, Ph), 3.76 (3 H, s, OCH3), 3.73 (3 H, s, OCH3);13C-NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 176.2, 150.5, 149.1, 147.3, 145.8, 143.5, 135.6, 133.1, 125.7, 122.6, 121.8, 111.2, 108.6, 54.9, 54.7; MS (m/z, %): 316.10 [M], 288.15 (81), 223.10 (24), 183.16 (100), 152.05 (67); Anal. Calcd for C15H16N4O2S: C, 56.94; H, 5.10; N, 17.71; S, 10.14%. Found: C, 57.28; H, 4.95; N, 17.45; S, 9.94%.

2-(4-Fluorobenzylidene)-N-(pyridin-3-yl)hydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5p)

Yellow solid.; Yield 82%; m.p. 200–201 ºC; Rf = 0.75 (n-hexane/ethyl acetate 1:0.25); FT-IR (KBr, υ) cm− 1: 3268, 3149, 3000, 2984, 1601, 1505, 1400, 1230, 1153, 1083, 1042, 627;1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 12.04 (1 H, s, NH), 10.27 (1 H, s, CH), 8.68 (1 H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, NH), 8.40 (1 H, dd, J1 = 1.2 Hz, J2 = 1.2 Hz, Ph), 8.17 (1 H, s, Ph), 8.02–7.96 (3 H, m, Ph), 7.43 (1 H, dd, J1 = 4.8 Hz, J2 = 4.8 Hz, Ph), 7.29 (2 H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, Ph);13C-NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ/ppm: 176.6, 161.9, 147.3, 141.8, 135.5, 133.4, 130.5, 129.7, 129.6, 122.8, 115.2; MS (m/z, %): 274.12 [M], 182.13 (100), 152.17 (49), 137.05 (30); Anal. Calcd for C13H11FN4S: C, 56.92; H, 4.04; N, 20.42; S, 11.69%. Found: C, 56.61; H, 4.13; N, 20.17; S, 11.93%.

In vitro anti-leishmanial assay

Reagents

Novy-MacNeal-Nicolle (NNN) (Brain-Heart Blood Agar, Luria Broth, Merck, Germany) and Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI 1640) mediums, fetal bovine serum (FBS), and Pen-Strep (penicillin 100 U/mL)/streptomycin 100 µg/mL) (Gibco, Germany), DMSO, tetrazolium salt (MTT, Sigma-Aldrich), and FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (Mab Tag, Germany) were procured and stored at the recommended temperatures until testing. All synthesized derivatives (5a-p) were initially dissolved/dispersed in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) to prepare a stock solution of 5mg/mL. The final concentration of DMSO was maintained below 1%, which does not exhibit harmful effects on the parasites34,35. Derivative dilutions were prepared in PBS to evaluate the impact of serial concentrations of 3.12–1000 µM on the macrophage, amastigote, and promastigote cells36,37,38. Amphotericin B 50 mg, Cipla (AmpB), and meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime®, Sanofi, 1.5 5g/mL ampules) (GLU) were used as positive control drugs in promastigote and amastigote forms, respectively.

Cultivation of Leishmania spp.

The standard Iranian strains of L. tropica (MRHO/IR/02/Mash10) and L. major (MRHO/IR/75/ER) were kindly provided by Dr. Ghaffarifar, Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran. Promastigotes were cultured in NNN medium and subsequently sub-cultured in RPMI 1640 enriched with 20% heat-inactivated FBS and 1% Pen-Strep, including streptomycin (100 µg/mL) and penicillin (200 IU/mL), at 18–24 °C36,37.

J774 A.1 macrophage cell culture

J774A.1, the murine macrophage cell line, was bought from the Pasteur Institute, Iran. The cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 12% FBS in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Upon reaching confluency, fresh media was added to the flasks36,37,38.

Anti-leishmanial activity

Anti-promastigote effects

Parasite counting method

The number of viable promastigotes of L. major and L. tropica was counted using the microscopic counting method to evaluate the effects of different concentrations of various compounds36,38,39,40. To do this, 100 µL of RPMI 1640 medium with 1 × 106 promastigotes/mL during the growth phase was placed into 96-well culture plates, and then different amounts (3.12–1000 µM) of each compound were added for 24, 48, and 72 h at 24 °C. Further, the number of fixed parasites was directly counted in a Neubauer chamber at 400x magnification under the light microscope for three consecutive days. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. The positive control, AmB, 0.93 µM, was produced in sterile PBS according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A negative control, CTRL (-), was defined as three wells in each plate that did not contain any compounds.

MTT assay for promastigote viability

The MTT reduction method (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) was applied to investigate cellular viability. In this assay, 100 µL of RPMI 1640 containing 1 × 106/mL promastigotes at the logarithmic phase was cultivated in each of the 96-well ELISA plates. Then, the parasites were exposed to different concentrations of compounds (3.12 to 1000 µM). The remaining experimental procedures followed the previously described protocols35,36. The percentage of promastigote viability was calculated using the following formula: 100 × (absorbance of treated cells-absorbance of the blank/absorbance of control cells-absorbance of the blank), while the alive promastigotes were postponed in PBS without any drug, and the environment without promastigote was applied as a negative control, CTRL-(-), and blank, respectively. The 50% inhibition concentration (IC50) of all compounds was evaluated as the 50% decrease in cell viability of treated cells compared to untreated cells36,37.

Anti-intracellular amastigote activity

For evaluation of the anti-leishmanicidal activity against L. major and L. tropica intracellular amastigotes, 200 µL of 105 J774A.1 macrophage was cultured in each well of 12-well plates that had small round glass coverslips at the bottom and was incubated for 24 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. After incubation, the non-adhered cells were removed by washing with sterile PBS. Then, 200 µL of metacyclic promastigotes (1 × 106) at the stationary phase (10:1) were added to the adherent macrophages to infect macrophage cells. After 24 h, the infected cells were incubated with different concentrations of compounds (1.32–1000 µM) for 72 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and 95% relative humidity. Following incubation, cells were washed with PBS, fixed with methanol, and Giemsa stained. The number of infected macrophages and intracellular amastigotes (Leishman bodies) were counted under an optical microscope. The number of amastigotes in 100 macrophage cells was used to calculate the IC50. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. GLU 14.61 µM was used as the positive control36,37.

Maintenance macrophages or macrophage cytotoxicity assay

The primary and major host cells for Leishmania parasites are macrophages. The J774A.1 murine macrophage cell line was applied to evaluate the toxicity of compounds through the MTT colorimetric assay. Macrophage cells were cultured in a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 106 cells/well and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After 24 h, the supernatant containing non-adhered cells was removed, and then in the presence of numerous concentrations of the derivatives (1.32–1000 µM), the cells were incubated for another 72 h. The optical density of solubilized formazan crystals was evaluated using an ELISA reader (Bio-Rad, USA) at a wavelength of 570 nm. Each experiment was performed in biological triplicates. The 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) of various compounds was determined as the 50% decrease in macrophage cell viability of treated cells compared to untreated cells. The selectivity index (SI) is the ratio of the CC50 of macrophage cells to the IC50 of amastigotes36,37.

Flow cytometry assay

The Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (Mab Tag, Germany) was used to assess apoptosis induction in promastigotes exposed to IC50 concentrations of some effective compounds. Briefly, 1 × 106 promastigotes at the logarithmic stage, treated with IC50 concentrations of the compounds, were harvested, washed with a cold sterile PBS solution, and centrifuged for 15min at 1000 g. Subsequently, 5 µL each of Annexin-V and propidium iodide (PI), along with 400 µL of binding buffer, were added to cell pellets. The promastigotes were incubated at 25 °C in a dark place for 15min. The test was read using CyFlow Space flow cytometry (Sysmex-Partec, USA), and data were analyzed by FlowJo TM software (Vancouver, BC, version 10.5.3). All tests were accomplished in triplicate, and the percentage of necrosis and apoptosis was investigated for each tested compound36,40.

Statistical analysis

The mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for all triplicate experiments. Based on the mean percentage viability of promastigotes, amastigotes, and macrophage cells, the IC50 values for promastigotes and amastigotes, and CC50 values for J774A.1 macrophages, were determined. GraphPad Prism software was used to evaluate the results and analyze them. Repeated measures ANOVA was employed for the parasite counting method results analysis. Additionally, the one-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was applied to compare the IC50 and CC50 values of derivatives. The ratio of CC50 and IC50 of amastigotes was shown by the SI.

Computational studies

In silico pharmacokinetic prediction and physicochemical properties

The ADMETLab3.0 web server (https://admetlab3.scbdd.com) was used to evaluate the compounds’ drug-likeness and ADMET properties. ADMETlab 3.0 provides a comprehensive and efficient platform for assessing physicochemical properties and ADMET-related parameters in the early stages of drug discovery.

In silico metabolism of compounds in the presence of cytochrome P450

The SMARTCyp 3.0 online server (https://smartcyp.sund.ku.dk/mol_to_som) was used to predict the sites of metabolism of the derivatives by the cytochrome isoforms CYP3A4, CYP2D6, and CYP2C9.

In silico cardiotoxicity prediction

The Pred-hERG web server (http://www.labmol.com.br) was used to predict the cardiotoxicity of the tested derivatives. This method estimates the potential for hERG channel inhibition, which is associated with cardiotoxic effects, with an accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of approximately 89–90%.

Molecular docking study

The molecular docking study of the derivatives into the L. major Pteridine reductase 1 (LmPRT1) active site was performed using Autodock 4.2 software41,42. The crystal structure of LmPRT1 (PDB ID: 5L42) was retrieved from the PDB. The docking protocol followed the procedure described in a previous report43. Before docking, crystallized water molecules and bound ligands were removed from the protein structure. Kollman charges and polar hydrogen atoms were then added. The structures of derivatives were prepared and energetically minimized in HyperChem 8.0 software by the MM+ method. Then, the Gasteiger charges were added to compounds. Lastly, the pdbqt files of the enzyme and compounds, which were applied in docking, were provided with AutoDock tools.

Molecular dynamics simulations study

The GROMACS 2022.6 computational software performed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. The method was done by the MD technique from the previous work44. The Acpype tool was used to generate the topology files and other force field parameters for the selected compounds. Before energy minimization, water molecules were represented using a tip3p model and approximately 11,864 water molecules were present in the system. Appropriate amounts of counter-ions were added by replacing water molecules to ensure the overall charge neutrality of the simulated system that was comprised of LmPTR1, ligand, and water molecules. Amber99sb force field was used for the determination of all bonding and nonbonding interactions. Steepest descent followed by conjugate gradient algorithms was used for energy minimization of the protein-ligand complex. After the energy minimization process, the position restraint procedure was performed in association with NVT and NPT ensembles. An NVT ensemble was adopted at a constant temperature of 300 K with a coupling constant of 0.1 ps and a time duration of 500 ps. After temperature stabilization, an NPT ensemble was performed. In this phase, a constant pressure of 1 bar was employed with a coupling constant of 5.0 ps and a time duration of 1000 ps. The pressure was maintained at 1 bar with the Parrinello-Rahman barostat. The Particle Mesh Ewald, Lincs algorithm, and Lennard-Jones potential were used to treat the long-range electrostatic, covalent bond constraints, and van der Waals interactions, respectively. Finally, a 100 ns MD simulation was performed with monitoring of equilibration by examining the stability of the energy, temperature, and density of the system as well as the root-mean-squared deviations (RMSDs) of the backbone atoms.

Results and discussions

Rationale and design

Chemically, thiosemicarbazones are intermediates in the synthesis of 2-amino-1,3,4-thiadiazoles, and they reside in solution at an equilibrium between the ring-closed and open-chain forms (ring-chain tautomerism)45,46. The thiosemicarbazone analogues were previously recognized in the anti-parasitic compounds. Thiosemicarbazones were initially discovered as inhibitors of parasitic cysteine proteases, such as rodhesain in T. brucei and cruzain in T. cruzi. Some members of this group of derivatives were inactive on the enzyme but active on parasites47,48. Several studies have explored the anti-leishmanial activity of thiosemicarbazones. For instance, Eldehna et al.. reported the synthesis of arylnicotinic acids conjugated with arylthiosemicarbazides and evaluated their anti-leishmanial properties. Their results showed promising activity, particularly for thiosemicarbazide derivatives, which outperformed the semicarbazide counterparts. This enhanced activity may be attributed to the greater lipophilicity of thiosemicarbazides, facilitating their penetration through parasitic membranes and improving target accessibility. This hypothesis is further supported by the higher CLogP values observed for thiosemicarbazide derivatives (Compound 1, Fig. 3)49. Fonseca et al. developed sugar analogues of thiosemicarbazones that inhibited parasite cysteine proteases. Structural modifications, such as the removal or substitution of the thiosemicarbazone moiety with semicarbazone, led to loss of activity, while alterations to the sugar component also reduced potency. These compounds showed efficacy against S. mansoni, T. brucei, and T. cruzi (Compound 2, Fig. 3)50. Moreira et al. described a series of aryl thiosemicarbazones against cruzain and anti-T. cruzi inhibitors. According to findings, thiosemicarbazones were introduced as selective and potent anti-T. cruzi agents. Anti-T. cruzi activity was shown to be reliant on the nature of the substituent used, whereas the substituent position in the phenyl ring had less significance for activity (Compound 3, Fig. 3)51. Linciano et al. identified several thiosemicarbazone derivatives with activity against intracellular amastigotes of T. cruzi, L. infantum, and T. brucei. Their findings supported the use of thiosemicarbazones as a viable scaffold for anti-parasitic drug development (Compound 4, Fig. 3)48. Manzano et al.. recognized some thiosemicarbazones with good activity against L. donovani amastigotes, with the most active compound showing an EC50 of 0.8 µM and minimal toxicity on two diverse mammalian cell lines (Compound 5, Fig. 3)52. Tenório et al. examined thiosemicarbazones substituted with nitro groups at the arylhydrazone moiety for their anti-Toxoplasma gondii activity. These compounds demonstrated efficacy against T. gondii without inducing morphological changes in host cells (Compound 6, Fig. 3)53. Thiosemicarbazones, on the other hand, are well-known for their wide range of biological activities, among which anti-leishmanial potential stands out (Compounds 7–14, Fig. 3)53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60.

According to previous studies, the structure-activity relationships (SAR) of thiosemicarbazone derivatives against leishmania can be summarized as follows: Halogen substituents, such as chlorine and bromine were well tolerated at the meta-position on the phenyl ring. Furthermore, modification of the methyl substituent at the ortho-position had only a minor effect. The presence of sulfur and methine bonds was found to be critical for biological activity. Moreover, the incorporation of bulky substituents on the side chain was generally associated with a reduction in efficacy24,61. The introduction of fluorine atoms on the phenyl or benzyl group attached to the N-iminothiourea moiety had a positive influence on the anti-leishmanial activity. This effect is likely attributed to the increased lipophilicity of the C-F bond compared to the C-H bond, despite their similar atomic sizes60. Based on the results, the hydrophobic character of the phenyl moiety plays a significant role in optimizing anti-leishmanial activity57. Furthermore, the SAR findings have shown that the activity of thiosemicarbazone derivatives largely depends on the electronic nature of the substituents attached to the NH group of the thiosemicarbazone core and the phenyl ring55. The present research has synthesized thiosemicarbazone analogues with electron donor substituents, electron-withdrawing substituents, and heteroaromatic rings at the NH of the thiosemicarbazone moiety and different groups at the para- and/or meta-phenyl rings. These analogues are currently being evaluated against Leishmania parasites, marking the first report of such compounds in this context. Additionally, in-silico studies were conducted to support the structure-based design. Previous research served as the foundation for the current study’s design rationale (Fig. 3).

Synthesis

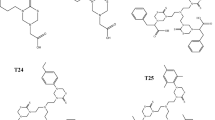

We have previously reported the synthesis as well as the antioxidant, anti-cancer, and anti-bacterial activities of a series of substituted 3-benzylidene-2-imino-4-phenyl-3H-thiazole62. In this study, we reported a one-pot, two-step, three-component protocol for the synthesis of thiosemicarbazone analogues, starting from hydrazine, substituted benzaldehyde, and various isothiocyanates. The reaction sequence begins with the nucleophilic attack of hydrazine on the substituted isothiocyanate, forming a thiosemicarbazone intermediate. This is followed by a condensation reaction between the resulting intermediate and an aromatic aldehyde, leading to the formation of the final thiosemicarbazone analogues. Pyridine-3-isothiocyanate, methyl isothiocyanate, and nitro-isothiocyanate were used as starting materials in the synthesis. The preparation of the thiosemicarbazone analogues (5a-p) is illustrated in Scheme 1, and their chemical structures are presented in Fig. 4.

Spectroscopic techniques were employed to identify and confirm the structures of all synthesized compounds (FT-IR1, H-NMR13, C-NMR, as well as mass and elemental analysis).

The FT-IR spectra of compounds (5a-p) showed NH stretching bonds in the range of 3416 –3318 cm− 1 and 3159 − 3134 cm− 1. The -C = N stretching vibrations appeared between 1633 –1585 cm− 1, while aromatic C = C bonds were observed in the ranges of 1560 –1503 cm− 1 and 1481 − 1400 cm− 1. The C = S stretching was identified between 1089 –1048 cm− 1, whereas C-N and C-S stretching bonds were determined at 1237 –1156 cm− 1 and 639 − 617 cm− 1, respectively. In the ¹H-NMR spectra, NH protons of the carbothioamide group appeared as distinct signals between 12.04 and 11.22 and 8.68–7.93 ppm. The imine proton resonated in the range of 10.27–8.30 ppm, and aromatic hydrogen was observed between 6.7 and 8.4 ppm. Peaks belonging to methoxy and methyl proton bonds were detected at 3.84–3.42 and 3.04–2.33 ppm, respectively. The ¹³C-NMR spectra exhibited thiourea carbon (C = S) resonances between 177.8 and 175.3 ppm, and the imine carbon appeared between 140.2 and 148.8 ppm. Aromatic carbon atoms resonated within the range of 150.3-125.6 ppm. Peaks belonging to methoxy and methyl carbons were observed in the range of 20.8-115.5 ppm.

The plausible mechanism for the one-pot, two-step, and three-component synthesis of thiosemicarbazone Schiff base derivatives (5a-p) is illustrated in Scheme 2. In step I of the reaction, hydrazine reacts with a substituted isothiocyanate to form a thiosemicarbazone intermediate 3. Subsequently, in step II, this intermediate undergoes condensation with a substituted benzaldehyde to initially generate a carbinolamine intermediate. Under acidic conditions, the carbinolamine undergoes dehydration, eliminating a water molecule to afford the final thiosemicarbazone Schiff base analogues.

The efficiency and yield of the synthesis of these compounds were primarily influenced by several key factors: electronic effects of substituent groups (electron-withdrawing or electron-donating), steric effects, hydrogen bonding ability, and nature of the heterocyclic ring substituent. Based on these factors, compounds having methoxy at the para-phenyl ring and especially two methoxy at the para- and meta-phenyl ring showed the highest increases in yield. This enhancement is attributed to the strong resonance electron-donating nature of methoxy groups, which stabilizes intermediates and facilitates the condensation reaction. Similarly, compounds with methyl at the para-phenyl ring also provide high yields but less than methoxy substituent because the methyl group is an inductive electron-donating substituent. In contrast, compounds bearing electron-withdrawing substituents such as fluorine or bromine at the para-phenyl ring tend to lower yields, especially when strong resonance electron-donating substituents are absent. Beyond aromatic substitution, the nucleophilicity of the hydrazine derivative significantly influenced reaction efficiency. N-methylhydrazine generally exhibits good nucleophilicity with higher yields, while N-nitrohydrazine has weaker nucleophilicity but strong electron-donating substituents on the aromatic ring (like dimethoxy at the para- and meta-phenyl ring) can compensate and maintain high yields. N-(pyridin-3-yl), due to its heterocyclic and electron-withdrawing nature, showed lower nucleophilicity, yet still provided moderate yields when combined with potent resonance donors. Steric effects also played a crucial role. Bulkier substituents, such as bromine atom, introduced steric hindrance that modestly decreased yield. In contrast, smaller substituents like fluorine and methyl cause less steric hindrance. Overall, the highest yields were achieved when a favorable balance of electronic effects (resonance and inductive), nucleophilicity, and steric hindrance was attained. In general, compounds with strong resonance donors and synthesized from highly nucleophilic hydrazines demonstrated the greatest synthetic efficiency (Table 1).

Anti-leishmanial activity

Anti-promastigote effects

The average number of L. major and L.tropica promastigotes at prearranged concentrations was counted in the presence and absence of all analogues and AmB for 24, 48, and 72 h at 24 °C (Table 2). Among the tested derivatives, compounds 5g, 5b, 5a, 5e, and 5f demonstrated a significant reduction in promastigote count relative to both the untreated control and less active derivatives such as 5p, 5i, and 5l (p < 0.001). However, these active compounds did not exhibit statistically significant differences in comparison with AmB as a positive control (p > 0.05), suggesting a comparable anti-promastigote effect. The results also revealed that the proliferation profile followed a dose-dependent response. The impact was more intense at higher concentrations (p < 0.05). On the other hand, 1000, 800, 400, and 6.12 µM concentrations showed the highest and lowest efficacies, respectively, in inhibiting the growth of L. major and L. tropica promastigotes. Notably, compounds 5c and 5h showed only mild and/or no effect, respectively, on both L. major and L. tropica promastigotes after 72 h. Similarly, compound 5j showed a mild effect, while 5k-m, 5n, and 5o demonstrated limited activity, with no statistically significant difference compared to the negative and positive controls (p > 0.05).

The metabolic activity of promastigotes and cytotoxicity of compounds were evaluated by MTT assay for 72 h of normal incubation. This colorimetric method was employed to validate the findings obtained through routine microscopic examination. Among the tested compounds, compounds 5a, 5b, 5e, 5f, and 5g exhibited notably higher activity, significantly reducing promastigote viability in both L. major and L. tropica compared to other derivatives (p < 0.001). The IC50 values in the L. major promastigotes treated with more efficient compounds, including compounds 5g, 5b, 5a, 5e, and 5f, were 26.7, 38.3, 54.3, 159.7, and 159.7 µM after 72 h, respectively. These results in L. tropica promastigotes were 101.5, 199.8, 258.0, 92.3, and 240.0 µM for compounds 5g, 5b, 5a, 5e, and 5f, respectively. The IC50 values of compounds 5p, 5i, and 5l were in the range of 31.9, 88.8, and 346.0 µM, respectively, against L. major and 313.9, 185.9, and 331.1 µM, against L. tropica promastigotes. Notably, none of the tested compounds showed a statistically significant difference in activity when compared to AmB as a reference drug (p > 0.05). This indicates that although several compounds were promising but not superior to the standard treatment.

Anti-amastigote effects

Moreover, it is well known that the clinical stage of the Leishmania genus is related to the amastigote parasite, which is the intracellular proliferation form in mammalian cells5. Therefore, the synthesized compounds at various concentrations were tested against L. tropica and L. major amastigotes. As revealed in Table 2, most of the screened compounds were notably toxic to macrophage infection and decreased the overall number of intracellular amastigotes (compounds 5g, 5b, 5a, 5d, 5e, and 5f); one possesses less anti-leishmanial activity (compound 5h), whereas compound 5c had moderate activity on reducing macrophage infection and amastigotes of both L. tropica and L. major toward the untreated control groups (P < 0.001). Among these, compounds 5g, 5b, 5a, 5e, and 5f also showed statistically significant differences in activity compared to GLU, as standard drug used in the amastigote assay (P < 0.05). The best IC50 value was observed first in 5g (18.8 µM), then 5e (31.8 µM), and 22.7 µM and 24.5 µM against L. major and L. tropica amastigotes. These results were significantly superior to GLU (P < 0.001), suggesting the strong potential of these compounds as anti-leishmanial agents (Table 2).

Among the synthesized derivatives, compounds 5p, 5i, and 5j, even at the lowest concentration (6.12 µM), reduced significantly macrophage infections and decreased the number of intracellular amastigotes compared to the positive control groups (P < 0.001). Additionally, derivatives 5o, 5n, and 5k-m remarkably reduced the number of amastigotes by up to 20–25% toward the untreated negative control (p < 0.05) (Table 1). Regarding potency, compound 5p exhibited the most effective activity against L. major amastigotes, with an IC₅₀ value of 31.2 µM, showing significant superiority over GLU (P < 0.001). In contrast, compound 5i showed the least effect on L. tropica amastigotes with an IC50 value of 185.9 µM (Table 2).

These findings also highlight a notable distinction between the parasite’s two life stages: the IC₅₀ values for intracellular amastigotes were consistently higher than those observed for promastigote forms, suggesting greater resistance of amastigotes to treatment (P < 0.001). This variation underscores the importance of targeting the clinically relevant amastigote stage in anti-leishmanial drug development.

Macrophage cytotoxicity assay

To further evaluate the safety profile of the synthesized compounds, a cytotoxicity MTT assay was conducted on uninfected J774A.1 macrophage cells, which were incubated with varying concentrations of the derivatives over 72 h (Table 2). Compounds cytotoxicity for J774A.1 macrophages and amastigotes IC50 was compared using the selectivity index (SI), the ratio between the CC50 and IC50 amastigote values. An SI ≥ 10 was considered indicative of a non-toxic and selective compound. As shown in Table 2, among the derivatives showing notable anti-leishmanial efficacy, compounds 5e-g, 5i, and 5p demonstrated low cytotoxicity toward macrophages and maintained favorable SI values, thereby indicating good selectivity toward Leishmania amastigotes. In contrast, several other derivatives exhibited either lower SI values or higher cytotoxicity. Notably, the selectivity of these active compounds was significantly better than GLU, the reference drug used in the assay (P < 0.001).

Apoptosis study

To investigate the mechanism underlying the anti-leishmanial activity of the most effective thiosemicarbazone derivatives (5a, 5b, 5e, 5f, 5g, 5i, and 5p), apoptosis induction was assessed in L. major and L. tropica promastigotes treated with their respective IC₅₀ concentrations. The results showed that these compounds displayed different early and late apoptosis as well as necrotic activities against L. major and L. tropica promastigotes. The apoptosis percent at IC50 concentrations for compounds 5a, 5b, 5e, 5f, 5g, 5i, 5p, and GLU were 36.2%, 41.5%, 37.7%, 16.19%, 52.9%, 22.14%, 42.2%, and 30.14%, respectively. All tested compounds induced more apoptotic effects than GLU (P < 0.05) except compounds 5f and 5i (P > 0.05). Compounds 5g and 5p showed higher apoptotic effects than other analogues and GLU (p < 0.001) (Fig. 5).

Structure-activity relationship studies

Anti-leishmanial activity against L. major

The thiosemicarbazone analogues (5a-p) were investigated against the amastigote and promastigote L. major. The IC50 values of the synthesized derivatives were determined and compared to the GLU and AmB drugs (Table 2).

Within the 2-(substituted benzylidene)-N-methylhydrazine-1-carbothioamide series (5a-h), electron-donating groups (EDGs) or electron-withdrawing groups (EWGs) at the para-position of benzylidene ring maintained the effect on amastigotes and promastigotes. Anti-promastigote and anti-amastigote activities were further decreased for substitution with moderately-sized EDG (-CH3 and N(CH3)2) (compounds 5c and 5h). In contrast, within the 2-(substituted benzylidene)-N-nitrohydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5i-l) and the 2-(substituted benzylidene)-N-(pyridine-3-yl)hydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5m-p), incorporation of a small, lipophilic EWG such as fluorine (compounds 5i and 5p) enhanced the anti-amastigote and anti-promastigote activities compared to other substitutions. Conversely, the introduction of EDGs (e.g., -CH3 and OCH3; compounds 5l and 5m) and/or moderately-sized EWGs like bromine (compound 5j) further reduced anti-amastigote and anti-promastigote activities.

Within the 2-(substituted benzylidene)-N-methylhydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5a-h) series, replacing OCH3 substitution in compound 5g with bromine in compound 5e decreased anti-promastigote and anti-amastigote activities. Changing moderately EWG (bromine, compound 5e) with strongly EWG (NO2 and flourine, compounds 5d and 5f) dramatically reduced activity against amastigote and promastigote forms. Notably, the presence of fluorine at the para-position of the benzylidene ring decreased activity compared to nitro at the same position, suggesting that increased volume, electron-withdrawing strength, and hydrophilicity may negatively impact leishmanicidal activity, contrary to earlier hypotheses suggesting these factors would enhance efficacy56. In contrast, a comparison of three compounds, 5c, 5g, and 5h, with EDGs at the para-position of benzylidene ring showed that compound 5g with OCH3 substitution improved anti-leishmanial activity compared to 5c (CH3) and 5h (N(CH3)2). This observation contradicts the previously assumed trend, where increased volume and lipophilicity were expected to correlate with decreased activity against L. major. Such discrepancies may be explained by the complex interplay between the electronic nature (EDG vs. EWG) of substituents and other physicochemical properties influencing the compounds’ behavior against both promastigote and amastigote forms. Two-substituted benzylidene in compound 5a showed lower anti-leishmanial activity than mono-substituted benzylidene in compound 5g. This can be due to the existence of two ortho OCH3 substitutions relative to each other, which changes the conformation of the compound compared to mono-substituted benzylidene. A comparative analysis of compounds 5a and 5b with two substituents on the benzylidene displayed that replacing the OCH3 group with OH at the para-position of benzylidene increased anti-promastigote activity while it decreased anti-amastigote activity. These findings suggest that the presence of EDG and lipophilic at the para-position benzylidene changed activity. Moreover, the potential formation of intramolecular hydrogen bonds between hydroxyl and methoxy groups may further impact the molecular conformation, thereby altering biological activity. Thus, subtle structural modifications, especially in the substitution pattern and electronic properties of the benzylidene ring, play a critical role in modulating compound efficacy against Leishmania species.

Within the 2-(substituted benzylidene)-N-nitrohydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5i-l) series, compound 5i, with fluorine at the para-position of the benzylidene ring, revealed the highest activity on promastigote and amastigote forms. A comparative analysis of three compounds, 5i (fluorine), 5j (bromine), and 5l (CH3), exhibited that an increase in EWG strength and lipophilicity positively influenced biological activity. However, two-substituted benzylidene (5k, meta- and para-OCH3) showed the lowest activity. According to the results, two-substituted benzylidene exhibited lower anti-leishmanial activity compared to mono-substituted benzylidene, which could be due to the change in the conformation of the compound.

Within the 2-(substituted benzylidene)-N-(pyridine-3-yl)hydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5m-p) series, compound 5p with fluorine at the para-position benzylidene ring revealed significantly higher anti-promastigote and anti-amastigote activities than compounds 5m (OCH3) and 5n (bromine). These results suggest that small-sized and strong EWGs increased anti-leishmanial activity. Furthermore, consistent with trends observed in other structural series, this set of compounds also demonstrated that two-substitution on the benzylidene ring markedly reduces biological activity. This reduction is presumably due to conformational changes and an increase in molecular volume, which may hinder proper interaction with the biological target or reduce membrane permeability.

Generally, two series of the 2-(substituted benzylidene)-N-nitrohydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5i-l) and the 2-(substituted benzylidene)-N-(pyridin-3-yl)hydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5m-p) showed lower anti-leishmanial activity than the 2-(substituted benzylidene)-N-methylhydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5a-h) series. This suggests that small-sized, EDG, and lipophilic substituents (e.g., CH3) at the carbothioamide moiety are more favorable for activity against both amastigote and promastigote forms of L. major than bulkier, EWG, and more hydrophilic groups (e.g., NO2 and/or pyridine).

Anti-leishmanial activity against L. tropica

The thiosemicarbazone analogues (5a-p) were investigated on amastigotes and promastigotes of L. tropica. The IC50 values of the synthesized derivatives were determined and compared to the GLU and AmB drugs (Table 2).

Within the 2-(substituted benzylidene)-N-methylhydrazine-1-carbothioamide series (5a-h), compound 5e, having bromine at the para-position of the benzylidene ring, showed the highest anti-leishmanial activity. Replacing bromine with OCH3, compound 5g, was the most potent compound after compound 5e. The existence of OCH3 somewhat reduced activity on the promastigote form while it was maintained against the amastigote form. Placing NO2, fluorine, CH3, and N(CH3)2 at the para-position of benzylidene in compounds 5f, 5d, 5c, and 5h, respectively, significantly decreased anti-promastigote and anti-amastigote activities of L. tropica. Based on findings, the presence of EWG and moderate size displayed a positive effect on anti-leishmanial effect. Besides, a comparison of two compounds, 5a and 5b, having two-substituted benzylidene showed that compound 5b with an OH group at the para-position was more potent than compound 5a with an OCH3 group at the same position. Similarly, the presence of EDG and bulk groups decreased anti-leishmanial activity.

Within the 2-(substituted benzylidene)-N-nitrohydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5i-l) series, compound 5i (fluorine) was significantly more potent than compounds 5j (bromine) and 5l (CH3). The results indicate that increases in lipophilicity, EDG, and bulkier substituents negatively impacted both anti-promastigote and anti-amastigote activities. On the other hand, the presence of two-substituents on the benzylidene ring in compound 5k decreased anti-leishmanial activity compared to mono-substituted (compounds 5i and 5l). This decrease may be attributed to the presence of the OCH3 group at the ortho-position, which likely alters the molecule’s conformation.

Within the 2-(substituted benzylidene)-N-(pyridine-3-yl)hydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5m-p) series, compound 5p (fluorine) showed higher anti-leishmanial activity than compounds 5m (OCH3) and 5n (bromine). It seems that the presence of small size, moderate lipophilicity, and strong EWG substitution at the para-position of benzylidene increased anti-leishmanial activity. Additionally, consistent with observations in the previous series, two-substituted the benzylidene ring decreased anti-leishmanial activity compared to mono-substituted (compound 5o vs. compounds 5m, 5n, and 5p).

Similar to anti-leishmanial activity observed against L. major, two series of the 2-(substituted benzylidene)-N-nitrohydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5i-l) and the 2-(substituted benzylidene)-N-(pyridine-3-yl)hydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5m-p) showed lower anti-leishmanial activity than the 2-(substituted benzylidene)-N-methylhydrazine-1-carbothioamide (5a-h) series.

Generally, all three series of derivatives exhibited higher activity against L. major than L. tropica, while the overall tendency of anti-leishmania activity against promastigote and amastigote forms was similar in both L. major and L. tropica species. Among two-substituted compounds (5a, 5k, and 5o), compound 5a with a CH3 at the hydrazinecarbothioamide moiety was significantly more potent than 5k (NO2) and 5o (pyridine). While 5k and 5o showed almost similar activity against L. major. Moreover, compound 5a showed remarkably higher activity compared to compounds 5k and 5o. Besides, compound 5k was strangely more potent than 5o against L. tropica. These findings show that the presence of CH3 (EDG) at the hydrazinecarbothioamide moiety remarkably increased anti-leishmanial activity compared to nitro and pyridine (EWGs) against both L. major and L. tropica. On the other hand, the presence of nitro and pyridine exhibited almost similar activity against L. major, while nitro showed stronger activity against L. tropica. It seems that the presence of bulk and EWG had a negative effect on L. tropica, but the bulk feature was not important for L. major.

In the group of fluorine-substituted para-phenyl compounds (5d, 5i, and 5p), compound 5p, which incorporates a pyridine ring, exhibited the highest potency overall. Among the others, 5d was more active than 5i against L. major, while 5i showed greater activity against L. tropica compared to both 5d and 5p. Additionally, compound 5d was slightly less active compared to 5p against the amastigote form, though their overall activities were comparable against L. tropica. These observations suggest that increased lipophilicity at the hydrazinecarbothioamide moiety enhances anti-leishmanial activity, particularly against L. major. Among mono-substituted compounds with bromine in the para-phenyl ring (5e, 5j, and 5n), compound 5e showed remarkably higher activity compared to compounds 5j and 5n. Compound 5j was slightly more potent than compound 5n against L. major. A similar trend was observed against L. tropica, with the exception that compound 5n showed considerably higher activity than 5j. According to findings, in these compounds, EDG and small-size groups at the hydrazinecarbothioamide moiety showed higher anti-leishmanial activity against L. major and L. tropica. However, increasing lipophilicity and size is not critical against L. major, but it is effective against L. tropica. Among mono-substituted compounds with OCH3 in the para-phenyl ring (5g and 5m), compound 5g displayed superior activity than compound 5m against both L. major and L. tropica. It looks like, in these compounds, the presence of EDG and a small size group at the hydrazinecarbothioamide moiety showed higher anti-leishmanial activity. In general, all evaluated derivatives exhibited greater potency against L. major than L. tropica.

Overall, the EDG or EWG substitution at the para-position of the phenyl ring retains the anti-promastigote and anti-amastigote activities56,63. Notably, small and lipophilic EWGs, such as fluorine, improved the anti-leishmanial activity56,57,59. Moreover, moderately sized and lipophilic substituents, including the EDG (-OCH3) and EWG (-Br), also contributed to improved activity. Substitution with EWGs like nitro and pyridine at the hydrazinecarbothioamide moiety revealed less activity than the CH3 group56,59. All derivatives exhibited higher anti-promastigote activity against L. major than GLU, except for compounds 5c, 5h, 5k, 5m, 5n, and 5o. Moreover, several compounds were more potent than GLU against the L. major amastigote form. Regarding L. tropica, all compounds exhibited higher anti-promastigote activity than GLU except compounds 5b, 5h, 5j, and 5o. While almost all compounds were more potent than GLU against the L. tropica amastigote form. Besides, all compounds displayed lower anti-leishmanial activity compared to AmB against both L. major and L. tropica. In general, the findings of current research are congruent with those of prior investigations57,58,59,63,64.

Furthermore, the cytotoxicity of compounds on the J774A.1 cell line was assessed. Among different parasite stages, amastigote inhibition is mostly more relevant therapeutically. Among the tested compounds, compounds 5c, 5h, and 5n showed the lowest cytotoxicity toward macrophages. However, compounds 5e and 5g exhibited the highest cytotoxicity (Table 1). The SI defined as the ratio of CC₅₀ to IC₅₀, was used to assess compound safety. For a molecule to be considered non-toxic, the SI should be at least 1020. Compound 5p with anti-leishmanial activity against L. major (IC50 = 31.2 µM on promastigote form and 12.77 µM on amastigote form; CC50 = 1218 µM) showed a SI of 95.4, showing a safe profile with admiration to macrophages. Following that, compounds 5a, 5e, and 5g showed the lowest toxicity for macrophages (CC50 = 1654, 847, and 733.2 µM) and showed promising anti-leishmanial activity (SI = 27.5, 26.6, and 39, respectively), indicating a safe profile for macrophages. In contrast, 5h (IC50 > 4450 on promastigote form and 2400 µM on amastigote form; CC50 = 3392 µM; SI = 1.4), 5l (IC50 = 346 µM on promastigote form and 680 µM on amastigote form; CC50 = 1062 µM; SI = 1.5), 5m (IC50 = 1000 µM on promastigote form and 891.6 µM on amastigote form; CC50 = 1332 µM; SI = 1.5), and 5o (IC50 = 1079 µM on promastigote form and 886 µM on amastigote form; CC50 = 1806 µM; SI = 2) because of the low anti-L. major activity, showed low selectivity.

Compounds 5e and 5g with anti-leishmanial activity against L. tropica (IC50 = 92.3 µM on promastigote form and 24.5 µM on amastigote form; CC50 = 847 µM) and (IC50 = 101.5 µM on promastigote form and 22.7 µM on amastigote form; CC50 = 733.2 µM) showed SIs of 34.6 and 32.2, resulting in a safe profile with admiration for macrophages. These results indicate a favorable safety profile, particularly with limited toxicity toward macrophages. In comparison, GLU showed SI equal to 10 and 8.09 against L. major and L. tropica, respectively, highlighting the superior selectivity of compounds 5e and 5g. Therefore, the most promising anti-leishmanial derivatives have a suitable scaffold to be investigated for further enhanced anti-parasitic drugs since they have an appropriate in-vitro early toxicity profile and selectivity on macrophages, particularly when it comes to compounds active against L. major and L. tropica.

Computational studies

Predicting in silico metabolic procedure in the existence of cytochrome P450

Drug-drug interactions may occur when foreign compounds, particularly drugs and their metabolites, influence the bioavailability of other drugs. Such interactions can lead to adverse effects, either due to the co-administration of multiple drugs or through drug–metabolite interactions65. Notably, more than half of all currently used drugs are metabolized by the three most significant enzymes in drug metabolism: CYP3A4, CYP2D6, and CYP2C9. Tables 3, 4 and 5 provide the top three atoms in compounds that have the highest metabolic priority.

According to the findings, the metabolic reactivity values of the derivatives are appropriate and comparable, providing a reliable basis for understanding their interactions with cytochrome P450 isoforms. Based on the SMARTCyp 3.0 analysis, the three atomic sites with the lowest scores in each compound were considered the most likely sites of metabolic transformation. For instance, the site with the highest score in derivatives 5a, 5c, 5d, 5e, and 5m is atomic site C11, and in compounds 5i, 5j, 5k, 5l, 5n, and 5p is atomic site S1 for isoform 2C9 (Table 3). For isoform 3A4, S1 is the main adduct formation site in derivatives 5i, 5j, 5k, 5l, 5m, 5n, 5o, and 5p, while in second rank, C11 is the main adduct formation site in derivatives 5a, 5c, 5d, and 5e (Table 4). Moreover, in compounds 5a, 5c, 5d, 5e, 5m, and 5o and compounds 5i, 5j, 5k, 5l, and 5p, atomic positions C11 and S1, respectively, are the key adduct formation sites for isoform 2D6 (Table 5).

In silico estimates of cyto-safe and cardiotoxicity

Cyto-safe and cardiotoxicity predictions are crucial for evaluating a sufficient level of safety earlier administration into the body. According to pred-hERG analysis, all derivatives—except for compounds 5m through 5p—were predicted to be non-hERG blockers, suggesting a low risk of cardiotoxicity (Table 6).

In silico estimate of pharmacokinetic and physicochemical features

Lipinski’s rule of five criteria includes molecular weight (MW) ≤500, hydrogen bond acceptors ≤10, hydrogen bond donors ≤5, and LogP value ≤5. Violations of these criteria may impair oral bioavailability. As shown in Table 7, all synthesized analogues complied with the MW and LogP requirements, having values below 500 and LogP < 5, respectively. Further, the compounds exhibited total polar surface areas (TPSA) ranging from 36.42 to 98.02 Ų and 4 to 7 rotatable bonds, which fall within the accepted thresholds for good oral bioavailability (TPSA ≤ 140 Ų; rotatable bonds ≤ 10). Additionally, all derivatives had an average of 3–8 hydrogen bond acceptors (nHA) and 2–3 hydrogen bond donors (nHD), satisfying Lipinski’s criteria and reinforcing their potential as orally active drug candidates.

P-glycoprotein (P-gp) is a transmembrane efflux transporter belonging to the ATP-binding cassette superfamily. It is widely expressed in biological barrier tissues, including the small intestine, liver, kidneys, and blood-brain barrier (BBB). P-Gp influences drug intestinal absorption since it can remove them from the cell66. According to the predictions, none of the synthesized analogues were identified as P-gp substrates, indicating a reduced risk of P-gp-mediated drug efflux and potentially improved oral bioavailability.

The ability of drugs to traverse the BBB is an important pharmacokinetic indication. Only drugs that have traversed the BBB can alter the physiological processes occurring in the brain67. The results showed that none of the produced analogues could pass through the BBB, suggesting limited central nervous system (CNS) exposure (Table 8).

Some CYP450 isoforms play a main role in drug metabolism. Derivatives were tested as inhibitors of Cyp3A4, Cyp2D6, and Cyp2C9. None of the analogues inhibited Cyp2D6. Analogues were not CYP3A4 inhibitors, except derivatives 5a, 5b, 5k, and 5m-p. Additionally, compounds 5j, 5k, 5m, and 5n were Cyp2C9 inhibitors, and compounds 5c, 5g, 5l, 5o, and 5p can possibly be Cyp2C9 inhibitors, whereas other analogues were not Cyp2C9 inhibitors (Table 8).

Carcinogenicity is one of the most critical adverse effects in the development of new drugs. Since carcinogenesis typically involves a long latency period before clinical manifestation, comprehensive long-term (often lifetime) animal studies are necessary to assess the carcinogenic potential of novel compounds. According to the predictions, all tested compounds were identified as potentially carcinogenic. Moreover, compounds 5a-c, 5e, 5f, and 5j-l did not display drug-induced nephrotoxicity, indicating a favorable renal safety profile for these analogues. Additionally, compounds 5f and 5i-l were not drug-induced neurotoxic, suggesting low neurotoxic risk (Table 8).

Molecular docking study

Computational approaches, such as molecular docking, are valuable tools for investigating enzyme-molecule interactions and aid in identifying the pharmacophoric features for the design of potential bioactive molecules with therapeutic uses68. This section aims to rationalize the observed in vitro anti-leishmanial activity by targeting a specific enzyme of the parasite. The enzyme of L. major pteridine reductase 1 (LmPTR1) was studied as a potential target. PTR1 is a short-chain NADPH-dependent oxidoreductase enzyme that plays a central role in the pterin salvage pathway69. Because the Leishmania parasite has a distinct ability to salvage pterins from its host, which absences PTR1 activity and instead synthesizes pterin analogues from GTP, the PTR1 gene becomes a critical target for therapeutic progression70. Many biochemical studies have confirmed that PTR1 is NADPH-dependent and functions in its tetrameric form71. This enzyme converts biopterin to H2 and H4 biopterin while also degrading other folate forms such as 7,8-dihydrofolate, and tetrahydrofolate. The removal of the PTR1 gene causes the insect phase promastigotes’ death; though, this result can be mitigated by giving lower pterins but not folates, implying that H4-biopterin serves an important function. Recent findings indicated that H4-biopterin is involved in regulating parasite differentiation. Mutants lacking PTR1 displayed decreased H4-biopterin levels, causing parasites in the sand fly vector to mature into the highly infectious metacyclic promastigote phase72.

The catalytic site of PTR1 contains a triad/tetrad composed of the Tyr, Asn, Ser, and Lys residues. It is identified that the Asp (e.g., Asp181) is more stable, comparable to a Ser residue. The pyrophosphate of the co-factor interacts with Arg17, stabilizing the enzyme-cofactor complex. Additionally, Phe113 plays a critical role in ligand stabilization within the active site, engaging in hydrophobic interactions that help anchor the substrate or inhibitor37,73. The inhibitor or substrate must bind to PTR1 in the presence of the co-factor NADPH74. The nicotinamide ring of NADPH engages in hydrophobic contact with Phe113, a key interaction that is essential for substrate recognition and catalytic activity. The catalytic residues Tyr191, Asp181, Lys198, and Tyr194 are highly conserved, suggesting that the catalytic mechanism of PTR1 is preserved across different Leishmania species75.

The docking poses were selected based on their optimal binding interactions and the top-scored conformations, as determined by the docking search algorithm and scoring functions. The binding affinities to PTR1’s active site were estimated based on high-scoring functions, the hydrogen bonds formed with key amino acid residues, and the spatial alignment of the docked compounds relative to the co-crystallized ligand. The docking methodology was validated by re-docking the co-crystallized ligand into the PTR1 binding site, which duplicated the initial pose determined from the PDB with an RMSD of 1.89 Å.

All of the analogues 5a-p were docked into the LmPTR1 active site to identify the optimum conformational position. Among them, compounds 5g and 5p showed the highest activity and the lowest free binding energy, correlating well with their observed in vitro activity. As illustrated in Fig. 6, the NHs of the thiosemicarbazides formed a hydrogen bond with Gly225 and two hydrogen bonds with co-factor NADPH in compound 5g. The methoxyphenyl moiety engaged in multiple hydrophobic interactions with Asp181, Pro187, Leu188, Phe113, Tyr194, Tyr191, Thr195, and Thr184. Furthermore, the thiosemicarbazone moiety formed hydrophobic interactions with Val230, Ser227, Leu229, Leu226, and Met183, contributing further to the stability of the binding pose (Fig. 6).

The phenyl ring formed a π-alkyl stacking interaction with the co-factor NADPH and a π-π stacking interaction with Phe113 in compound 5p. Moreover, the fluorine atom at the para-phenyl ring in compound 5p made a hydrogen bond with Ser111. The pyridine ring of compound 5p showed hydrophobic interactions with Pro187, Leu188, Thr184, Asp181, Tyr194, Thr195, and Tyr191. Furthermore, the sulfur atom of the thiosemicarbazone moiety made hydrophobic interactions with Tyr283, and the phenyl ring formed this interaction with Met183 and Gly225 (Fig. 7).