Abstract

An ultra-wideband (UWB) multiple input multiple output (MIMO) antenna with two ports, a low profile of 0.354λ0 × 0.734λ0, with good isolation is suggested. The antenna is designed to be compact and single-sided by using modified Koch fractal-based radiators in conjunction with coplanar waveguide (CPW) feeding. A slotted octagonal ground plane and an octagonal modified Koch fractal radiator with CPW feeding make up the basic antenna, which achieves a UWB response. MIMO capacity is achieved by placing two identical parts in opposite directions in a 180° rotational arrangement, which successfully realizes the diversity performance. The ground connection and strong isolation between the elements are established by a meander line construction positioned in the center. The antenna maintains an efficiency of over 86% and shows a peak gain of 6.1 dB. Additionally, it maintains acceptable MIMO diversity parameters like envelope correlation coefficient of less than 0.05, diversity gain of almost 10 dB, channel capacity loss of less than 0.4 bps/Hz, total active reflection coefficient of less than 10 dB, and mean effective gain ratio of 0 dB over the operating band, while achieving an impressive 10 dB impedance bandwidth (IBW) spanning (126.48%) from 3.24 to 14.39 GHz. Its exceptional performance is shown by the respectable outcomes of S-parameters and MIMO diversity evaluations, as well as a thorough time-domain study. Due to its high data rates, scalability, spectrum efficiency, and ease of integration, the UWB MIMO antenna could be suitable for internet of things-based security system for smart offices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In smart office networks, the internet of things (IoT) gadgets keeps opening up new opportunities1. Nowadays, a potted plant can sense when it is too cold or thirsty to water itself and adjust the temperature in the room. Sensors are being used to control everyday lighting, turning it on and off as you enter and exit a room. In a smart office network, machines like photocopiers and printers determine which devices are connected first. Offices that have linked devices are now smarter due to the merging of technologies like the Internet, Wi-Fi, and Bluetooth. In order to increase productivity, control expenses, manage inventory, and minimize tedious monitoring, connected devices including door locks, security cameras, vending machines, motion sensors, light bulbs, window blinds, and climate control systems now communicate with one another. Cognitive computing solutions that give control over surroundings enable communication between linked devices2. Figure 1 shows a potential example of a smart office connected by a high-speed wireless network.

During a cyberattack, all of the applications that the IoT has made possible could come to a halt, potentially leading to unexpected outcomes3. 70% of IoT wireless devices are not built to be secure, according to reported research4. It could be a lack of defense against attacks at work. Attacking internet-connected access points results in fatalities in addition to significant financial damages. Additionally, it gives hackers lawful access, enabling them to forge even more illegal links. Cyberattacks will inevitably rise tremendously as IoT adoption continues1. The company data, supply chain, and productivity will all be impacted by these attacks. Manufacturers of IoT devices must design sturdy products that support security and performance. To enable network segmentation and use the least privilege principle, the IoT devices need to be identified and verified. The data generated by IoT is the last essential component of its security. It is necessary to encrypt IoT data using encryption that is either integrated into the device or in the application that communicates with it5.

The short-range wireless communication technique known as ultra-wideband (UWB) makes use of radio waves. UWB offers extremely high degree of data security, made possible by time-of-flight (ToF) measurements. Because of its intrinsic encryption, random number generation, and other security features, UWB’s ToF capabilities make it more difficult for an outside attacker to access or alter UWB communications by precisely determining the time it takes for the signal to move between devices. UWB is perfect for high-speed, short-range data transmission because it can transport more data by using a wider bandwidth and operating in a higher frequency range. More accurate device location is ensured by UWB’s precision down to 10–30 cm6. For wireless communications, combining UWB technology with multiple input multiple output (MIMO) systems is a practical approach for achieving > 1 Gbps data rate7. By employing several antenna elements at the transmitter and receiver, MIMO technology can increase transmission throughput and decrease multipath fading. More sophisticated encryption algorithms can be used, which makes it more difficult for hackers to compromise the network. Data communication is more secure when encryption is stronger8.

As previously stated, UWB MIMO IoT wireless devices are mainly intended for usage in indoor communication systems with high-speed data rates. So, they require front-end communication devices that are portable, lightweight, and compact. Increased correlation between MIMO elements, low radiation efficiency, and distortion of the radiation pattern are all results of high mutual coupling in MIMO antennas9,10. To determine its diversity performance features, a MIMO antenna also needs to estimate various diversity parameters. Various matching and decoupling structures (DSs) were reported previously for improving the isolation to get around this constraint11,12.

Compact size, operating bandwidth, isolation, and other factors are the primary concerns for UWB MIMO antenna systems used in portable devices11,13. Since multiple antennas are placed closely together, radiation characteristics and antenna isolation are degraded in such systems. Therefore, in portable MIMO devices, designing a compact MIMO antenna with high isolation continues to be a difficult task for antenna researchers. To address the issue of space constraints between the antenna elements and achieve a compact antenna, it is extremely necessary to use a recursive process-based fractal methods14. The self-similar as well as space-filling behaviour of MIMO antennas with fractals is one of their most significant features. Fractal MIMO antennas can therefore offer a higher bandwidth, a better radiation pattern, and lesser correlated signals because they are simply self-similar, space-filling, and self-affine15,16. Also, the fractal-based compact MIMO antennas can be integrated with portable Wi-Fi and IoT devices without difficulty. Contributors from academia and the wireless industry have examined numerous wideband MIMO/diversity antennas with fractal radiators, such as a fractal circular ring radiator17,18, fractal loaded circular radiator19, Koch fractal20, molecule-shaped radiator21, modified Sierpinski carpet fractal22, Koch fractal23, circular ring24. Table 1 demonstrates the advantages, limitations, and application band for the MIMO antennas with fractal-based radiators, where it is noted that the suggested UWB antenna has IoT capabilities that can be utilized in a smart office security system.

This work presents the design of a compact UWB-operating octagonal fractal MIMO/diversity antenna. The suggested antenna consists of two modified octagonal Koch radiators with coplanar waveguide (CPW) feeding positioned vertically in the opposite orientation. To further enhance the isolation (S12/21 < −20 dB) between the radiators (ports), a meander line is added between the ground planes. The suggested antenna has a minimum efficiency of 83.1% and a maximum gain of 6.1 dB. Also, to determine whether the suggested antenna is appropriate for a diversity application, MIMO diversity parameters are examined.

Structure analysis of the suggested antenna

Antenna structure

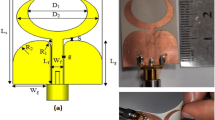

Figure 2(a) displays the structural design of the MIMO/diversity antenna. The diversity/MIMO antenna is printed on the FR4 substrate with a volume of 28 mm × 58 mm × 0.8 mm (\(\:{\epsilon\:}_{r}\)= 4.4 and tan δ = 0.02). The antenna contains two slotted octagon ground planes with two CPW feeding and two modified Koch fractal (MKF) octagonal radiators (shown in Fig. 2(b)) placed in opposite directions. The radiators are arranged to provide a miniaturized size and a large bandwidth (3.24–14.39 GHz). The surface current distribution of the antenna element of the proposed MIMO antenna is depicted in Fig. 2(c), which is compared with the current distribution in the TM11 mode of the circular patch (Fig. 2(d))25. As can be seen, the current distribution of the proposed antenna element is the same as the current distribution in the TM11 mode of the circular patch. This shows that the antenna element of the MIMO antenna is working in TM11 mode.

Structure of (a) MIMO/diversity antenna, (b) MKF octagon radiator with dimensions: (in mm; W1 = 58, L1 = 28, Wf = 3.5, Lf = 4.43, S1 = 5.74, S2 = 4.05, S3 = 2.87, S4 = 2.03, S5 = 1.43, R1 = 10.6, R2 = 7.5, R3 = 5.303, R4 = 3.75, P2 = 8.41, G1 = 0.5, G2 = 1, B1 = 3.21, B2 = 0.89, B3 = 1.36, H1 = 5.91, H2 = 1.79, H3 = 2.72, T1 = 1, T2 = 0.5, T3 = 0.5, W2 = 4, W3 = 3, L2 = 2, L3 = 1, L4 = 4.7), (c) TM11 mode in the proposed antenna, and (d) TM11 mode distribution in the circular patch.

Additionally, a meandered line is inserted between the two ground planes, to achieve an isolation more than 20 dB. Since the meander line is positioned between two antenna elements, the overall volume of the antenna will not increase. Thus, the need for small and affordable antennas for modern wireless applications could be satisfied.

Development of octagonal modified Koch fractal (MKF)

The geometry of a regular polygon acts as a resonator. The regular polygon creates multiple resonant frequencies within the antenna structure. These resonances occur at different frequencies, contributing to the antenna’s ability to operate across a wide range. Therefore, in the proposed antenna design, a polygon structure in the form of octagon is used. Initially, the octagonal radiator (OR) is formed based on a circular radiator (CR), as depicted in Fig. 3(a). As indicated by Eq. (1), the resonance frequency of an OR (shown in Fig. 3(b)) is determined by comparing the effective surface area of a CR to the area of a conventional OR26,27.

Here, Os is the side arm length of the CR = S1 = 5.74 mm and \(\:{R}_{eff}\) is the effective radius of the CR = 7.11 mm. The radius of CR is given by Eq. (2), and this can be utilized to describe the \(\:{R}_{eff}\)26,27.

where CR is the CR’s radius = 6.865 mm, Ts is the substrate thickness = 0.8 mm, and \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{r}\) = 4.4 is the substrate dielectric constant. Lastly, by equating Eqs. (1) and (2), the resonance frequency for an OR can be expressed as26,27,

This involves TMmn = T11 = 1.84118, Reff = effective radius for CR, c = speed of light = 3 × 1011 mm/sec, and \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{eff}=\left(0.5+{\epsilon\:}_{r}/2\right)\). The II and IV iterations of the initiator are also shown in Fig. 3(b). As can be seen in Fig. 3(c), the simulated first resonance frequency of 4.15 GHz is found to be quite similar to the calculated octagonal radiator (3.76 GHz) using Eq. (3) with a side length of 5.74 mm and TM11 mode (Fig. 3(c)). As the number of iterations increases, impedance matching improves at the mid-frequency range.

The Koch fractal approach, an iterative function system (IFS) based on affine transformation, is now used to the octagonal design in order to achieve a compact antenna27,28,29. First, as shown in Fig. 4(a), a straight line oriented horizontally is employed as a Koch initiator. The basic generator’s center segment is divided and replaced with the other two segments (W1 and W2) after the initiator, a straight line, is divided into three equal parts. To create an MKF antenna, a square element is etched on a larger octagonal patch in the first iteration. The resulting material is then added to the smaller octagonal radiator, as shown in Fig. 4(b). This is the geometry’s initial iteration. The procedure is repeated to attain size compactness and enhance the antenna performance in the subsequent generation of higher iterations (Fig. 4(c)–(e)). This procedure enhances impedance matching while also lengthening the radiator’s electrical length. The IFS Koch curve generalization is expressed numerically using the given formulas27,

where the rotation angle (θ) and the scaling factor (k) are connected and can be stated as27,

The aforementioned expression shows that the distance between two inclined lines is the same in every iteration. The value of \(\:\theta\:\) for a typical Koch fractal curve should be π/3. The generator expression is the product of the previously mentioned equations and applies to all higher-order fractal iterations27.

The self-similar fractal structure dimension (D) is expressed in27 through the application of affine transformations (W(A)):

The preceding expression determines the D at θ (the indentation angle) is 2 when θ = π⁄2. Nevertheless, the conventional Koch fractal curve produces a D = 1.262 when θ = π⁄3. This result implies that the electrical length of the MKF is longer than that of the normal Koch fractal. Longer electrical lengths result in longer current paths and lower antenna cut-off frequencies.

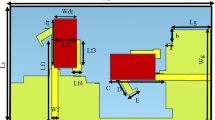

MIMO/diversity antenna structure

The diversity antenna’s optimized steps are arranged in Fig. 5, which also includes the related simulated reflection coefficients (S11/22) and isolation (S12/21) graphs. The first step (MIMO 1) has two octagonal radiators mounted opposite to each other to take advantage of the diversity performance of octagonal ground planes. Figure 6(a) makes it clear that the MIMO 1 antenna provides a wide bandwidth from 3.93 to 13.64 GHz, with just a small amount of mismatch between 7.3 GHz and 11 GHz. However, UWB applications are not covered by it. Moreover, the lower frequency region of the UWB range shows low isolation (> 17.81 dB) for MIMO 1 (Fig. 6(b)). To enhance matching at 7.3 GHz and 11 GHz, the main octagonal radiator in MIMO 2 is etched with the modified Koch generator that has been suggested. This offers good impedance matching from 4.24 to 13.27 GHz, which is less than < −11 dB. A 6 mm rectangular slot is inserted into the ground in MIMO 3 to enhance impedance matching in the lower UWB frequency range. This achieves a bandwidth of 3.38 to 13.14 GHz. At the vertices of the octagonal ground planes in MIMO 4, slots are added to further increase the bandwidth. This results in a broad frequency spectrum in the 3.16–13.81 GHz band by lengthening the antenna’s electrical length and providing an extra resonance at 13.2 GHz. From MIMO 1 to MIMO 4, low isolation (less than 20 dB) is attained in the lower UWB range. In MIMO 5, a meander line is inserted between the two ground planes to increase the inter-port isolation between the two octagonal fractal radiators at the lower frequency range. Here, the length of the meander line is \(\:\lambda\:/2\) at 3.3 GHz, which is connected at the two corners (upper and lower) of the grounds of antenna elements, which provides satisfactory isolation. Thus, a significant reduction in the mutual coupling (isolation of more than 20 dB) throughout the band of interest (3.38–14.15 GHz) is achieved.

Meander’s effect on inter-port isolation

Figure 7 shows the surface current distribution at 3.3 GHz frequency, which sheds more light on the effect of the meander line on inter-port isolation. For this, port 1 is excited and port 2 is terminated with a 50 Ω impedance. The antenna produces a significant current on both radiators (antenna A and B) in the absence of a meander line, as seen in Fig. 7(a). This implies that there is less isolation between the two antennas because ports 1 and 2 are mutually connected. However, when the meander line (shown in Fig. 7(b)) is introduced between the ground planes, relatively large currents accumulate on both the meander line and antenna A, but very little current flows to antenna B. This demonstrates the low level of interference between two antenna elements, which increases the isolation in the lower frequency band of UWB.

The meander line structure plays a crucial role in improving the isolation of the proposed antenna. Therefore, it is necessary to discuss the effect of the parameters of the meander line structure on the antenna performance. For the simulation, a fixed MIMO antenna geometry is taken and only meander line parameters are varied. First, the width (or thickness) of the meander line is varied and S11 and S21 are simulated as shown in Fig. 8(a). It shown that there is no significant change in S11, but isolation (S21) improved by keeping the values L2 = 2 mm and L3 = 1 mm. Secondly, the number of turns (N) of the meander increases from 1 to 4 and S-parameters (S11 and S21) are simulated, as presented in Fig. 8(b). There is also almost no change in the reflection coefficients, but isolation is enhanced by increasing N. Lastly, the length of turns of the meander line in varied, and S-parameters are simulated as displayed in Fig. 8(c). As shown, there is only a small change in S11, but the isolation is higher at the operating band at W3 = 3 mm. This shows that the electrical distance between antenna elements is progressively increased by increasing number of turns and keeping the adequate values of the width and length of turns of meander line, which increased the isolation without altering the S11. This satisfies the design requirements of isolation and a compact size of the MIMO antenna.

Results and discussion

Antenna measurement and fabrication

The proposed MIMO antenna is fabricated, and S-parameters are measured using a vector network analyser (VNA) by activating the port-1 and terminating the port-2 with a 50 Ω load. The outcomes of the simulated and measured transmission (S12/21) and reflection coefficients (S11/22) are shown in Fig. 9(a). The suggested antenna accomplishes a bandwidth from 3.24 to 14.39 GHz (measured) and isolation greater than 20 dB in an almost complete operating range with slightly lower isolation at 4 GHz of about 19 dB. Figure 9(b) shows the measured peak gain of the proposed antenna in the working band, which varies from 0.34 dB to 6.1 dB. Furthermore, the antenna’s gain primarily rises with frequency and falls particularly between 12 and 14 GHz. This effect is primarily caused by the lossy FR4 substrate. The gain comes back to 6 dB for the frequencies higher than 14 GHz due to compensating for the potential signal losses that can occur at the higher frequencies. Furthermore, Fig. 9(c) indicates that the simulated radiation efficiency of the antenna is higher than 87% and measured radiation efficiency is more than 86%.

Figure 10 displays the radiation patterns in the E-plane and H-plane planes for frequencies of 3.5 GHz, 5.5 GHz, 7.5 GHz, and 9.5 GHz. When antenna element-1 is activated by a source and element-2 is terminated with a load, radiation patterns are plotted. Figure 10 illustrates that co-polarized patterns in the E-plane radiate like a dipole, whereas the H-plane radiation patterns are almost omnidirectional. Moreover, the co-polarized patterns exhibit deformed shapes in the E- and H-planes as a result of the higher-order resonating modes. Additionally, the difference in amplitude between cross-polarization and co-polarization for the two primary planes (E- and H-planes) is less than −20 dB, suggesting that the received pulses were slightly distorted. However, the antenna basically keeps steady patterns over the UWB. There is some difference between the simulated and observed radiation patterns due to transmitting and manufacturing errors, but it is within adequate range.

MIMO diversity parameters

To take advantage of the benefits offered by the suggested MIMO/diversity antenna, different diversity performance parameters are examined. The evaluation of correlation and mutual coupling between the neighbouring antennas is evaluated using the ECC, which is reliant on the far-field antenna pattern30. ECC is formulated using the radiation patterns of the two-port MIMO/diversity system, which is computed by Eq. (11). While an uncorrelated MIMO antenna provides an ECC equal to zero, an ECC value between 0 and 0.5 is needed for an acceptable diversity performance. Figure 11(a) illustrates that the ECC values in the working band are less than 0.05.

where \(\:\overrightarrow{{F}_{i}}\left(\theta\:,\phi\:\right)\) is the 3D radiation pattern obtained when antenna first port is excited and second port is connected to match load.

Another important metric to estimate how well diversity performance works in a MIMO system is DG. The expression (12) provided in30 can be used to express it for ECC. The DG values, as shown in Fig. 11(a), are nearly 10 dB. Plots also demonstrate that the proposed antenna provides good diversity performance with minimal ECC and high DG throughout the operating bandwidth.

It is crucial to examine the antenna’s radiation properties in a particular multipath environment to accurately evaluate its performance. MEG is the ratio of the received power of an isotropic antenna to the received power of a MIMO/diversity antenna in a rich scattering situation. The MEG of the MIMO antenna is computed using Eqs. (13)–(15) in30. Achieving optimal diversity performance requires the MEG ratio to be within ±3 dB30. Figure 11(b) displays the MEG for both ports and the MEG ratio. The plot indicates that the MEG ratio is 0 dB throughout the operating range.

where \(\:{MEG}_{1}\) and \(\:{MEG}_{2}\) are given in Eqs. (14)–(15),

One of the key characteristics of a MIMO antenna is its CCL, which represents the losses in the MIMO/diversity wireless system as a result of the correlation between antenna elements. The CCL’s favourable value is less than 0.4 bits/sec/Hz to achieve a considerable MIMO/diversity system performance, which can be evaluated using the mathematical expression (16) in30. The CCL plot against frequency for the presented antenna is displayed in Fig. 11(c). The plot clearly shows that the CCL value is < 0.4 bits/sec/Hz in the UWB spectrum. Users may be able to transmit data at high-speed utilizing the suggested antenna because the CCL value is lower than the acceptable value.

In terms of S-parameters, \(\:{{\Psi\:}}^{R}\) is a 2 × 2 co-relation matrix that can be expressed as follows:

\(\:{{\Psi\:}}^{R}=\left[\begin{array}{cc}{\phi\:}_{11}&\:{\phi\:}_{12}\\\:{\phi\:}_{21}&\:{\phi\:}_{22}\end{array}\right]\), and

The proximate antennas may have an impact on the efficiency, gain, and bandwidth of the system when using many antennas at once. Because of this, the TARC is yet another essential metric for evaluating a MIMO/diversity antenna’s diversity performance. TARC is the square root of the ratio of total power incident to total power reflected, which is obtained using the scattering-parameters as shown in Eq. (17)30. TARC should preferably be not more than −10 dB for the MIMO/diversity system to operate as intended. Figure 11(d) shows that TARC values are < −10 dB over the working band, which results in all provided power being radiated in the air.

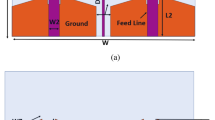

Time-domain analysis

IoT applications where exact timing and data integrity are crucial, especially in real-time settings, may encounter group delay, which is defined as the time difference between the arrival of several frequency components of a signal to a receiver. Minimizing reflections (S11) and mutual coupling (S21) is crucial for dependable operation in smart office applications, where numerous IoT devices communicate wirelessly. The suggested MIMO antenna’s time-domain properties are evaluated with an emphasis on group delay, the forward transmission (S21) coefficient, and the reflection coefficient (S11). Figure 12 illustrates the three different setups used for this investigation. One antenna acts as the transmitter (Tx), and the other one acts as the receiver (Rx). In order to create a far-field environment, a 20 cm separation was purposefully chosen to guarantee a lower resonance frequency of 2.53λ0. A 5th-order Gaussian pulse is used to excite the antennas, as described in,

Here, Gaussian pulse spread, time, and amplitude are represented by the symbols σ, t, and A, respectively. Figure 12(a)–(c) shows that the forward transmission coefficient (S21) and reflection coefficient (S11) steadily stay below −40 dB and −10 dB, respectively, across the assigned frequency range. Group delay characteristics are almost the same throughout the UWB. A satisfactory linear phase response in the operating band is indicated by a group delay of less than 1 ns. At the high frequencies, the group delay variation surpasses 1 ns for orientations that are side-to-side, face-to-face, and face-to-side. Phase non-linearity is the cause of this, as it is not limited to high frequencies.

Comparison table

Table 2 displays performance parameters of the proposed MIMO antenna in contrast with the existing MIMO/diversity antennas with fractal-based radiators. The proposed antenna has all the essential features such as connected ground, copper design on one side of substrate only, compact size, high isolation, high gain and efficiency as compared with other fractal-based MIMO radiators. Additionally, the proposed work provides MIMO/diversity and time domain analyses, which have not been done or done with an incomplete investigation. Although the UWB MIMO antenna in21 has an UWB with high isolation without a decoupling structure, but has various other limitations, which are stated in Table 1. These features demonstrate the proposed antenna’s suitability for UWB applications and IoT-based smart security systems in offices. In the future, by introducing metasurfaces into MIMO systems, phase, amplitude, and polarisation of the electromagnetic wave can be dynamically controlled, resulting in improved spatial multiplexing and signal targeting31,32,33. Also, MIMO antennas can be integrated with filters to create high-performance systems with improved isolation, enhanced bandwidth control, and high radiation efficiency, making them ideal for use in 5G, Wi-Fi, and IoT communication networks34,35.

Conclusion

An octagonal Koch fractal MIMO antenna with UWB properties is designed in this research. Utilizing two octagonal Koch fractal radiators, two slotted ground planes, and two CPW feedlines for high impedance matching, the proposed system offers a broad working bandwidth spanning from 3.24 to 14.39 GHz. To attain size compactness and isolation better than 20 dB, a decoupling structure is designed using a meander line, which is introduced between slotted ground planes. The diversity/MIMO antenna’s compact design makes it easy to install within portable wireless devices. The maximum gain and minimum efficiency of the proposed MIMO antenna are 6.1 dB and 86%, respectively.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Siwakoti, Y. R., Bhurtel, M., Rawat, D. B., Oest, A. & Johnson, R. C. Advances in IoT security: vulnerabilities, enabled criminal services, attacks, and countermeasures. IEEE Internet Things J. 10 (13), 11224–11239 (2023).

Abdul Moiz, Smart Office Needs Smart Security, Externetworks, [Online]. Available: https://blog.externetworks.com/smart-office-needs-smart-security/. [Accessed 23 November 2024].

Huang, C. et al. A robust approach for privacy data protection: IoT security assurance using generative adversarial imitation learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 9 (18), 17089–17097 (2022).

Iqbal, W., Abbas, H., Daneshmand, M., Rauf, B. & Bangash, Y. A. An In-Depth analysis of IoT security requirements, challenges, and their countermeasures via Software-Defined security. IEEE Internet Things J. 7 (10), 10250–10276 (2020).

Sun, J. & Zhou, S. Cuckoo search-ExtraTrees model for Radio-frequency power amplifier under different temperatures. Frequenz https://doi.org/10.1515/freq-2024-0298 (2025).

Ultra-Wideband Technology, AKER Technology, [Online]. Available: https://www.aker-usa.com/ultra-wide-band-technology/. Accessed 23 November 2024.

Roshna, T. K., Deepak, U., Sajitha, V. R., Vasudevan, K. & Mohanan, P. A compact UWB MIMO antenna with reflector to enhance isolation. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 63 (4), 1873–1877 (2015).

Chen, J., Wang, J., Wang, J. & Bai, L. Joint fairness and efficiency optimization for CSMA/CA-Based Multi-User MIMO UAV ad hoc networks. IEEE J. Selec. Topics Signal Process. 18 (7), 1311–1323 (2024).

Dai, M., Sun, G., Yu, H., Wang, S. & Niyato, D. User association and channel allocation in 5G mobile asymmetric Multi-Band heterogeneous networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 24 (4), 3092–3109 (2025).

Saeidi, T. et al. High Gain Compact UWB Antenna for Ground Penetrating Radar Detection and Soil Inspection, Sensors, 22 (14), 5183 (2022).

Amsaveni, A., Harish, L., Rashmi, S. & Kaiser, A. Performance analysis of pentagonal MIMO antenna with elliptical slots for 5G V2V communication. Int. J. Veh. Inf. Commun. Syst. 9, 103–113 (2024).

Alibakhshikenari, M. et al. A comprehensive survey on various decoupling mechanisms with focus on metamaterial and metasurface principles applicable to SAR and MIMO antenna systems. IEEE Access. 8, 192965–193004 (2020).

Mohanty, A. & Sahu, S. Design of 8-port compact hybrid fractal UWB MIMO antenna with a conjoined reflector-ground integration for isolation improvement. AEU- Int. J. Electron. Commun. Eng. 145 (2022).

Tripathi, S., Mohan, A., Yadav, S. & Compact Koch Fractal, A. UWB MIMO antenna with WLAN Band-Rejection. IEEE Antennas. Wirel. Propag. Lett. 14, 1565–1568 (2015).

Khade, S. S. & Bire, P. D. Fractal MIMO antenna for wireless application, Opt. Wirel. Technol. Proc. OWT, 546, 347–356 (2020).

Bhutani, P., Sagar, S. & Kumar, A. Performance analysis of Sierpinski carpet fractal antenna for wireless communication, Applications of Computing Automation and Wireless Systems in Electrical Engineering: Proceedings of MARC 2018, 749–758 (2019).

Alharbi, A. G. et al. Novel MIMO antenna system for ultra wideband applications. Appl. Sci. 12 (7), 3684 (2022).

Rohit Gurjar, D. K., Upadhyay, B. K., Kanaujia & Sharma, K. A novel compact self-similar fractal UWB MIMO antenna. Int. J. RF Microwave Comput. Aided Eng. 29 (3), 1–10 (2018).

Addepalli, T. et al. Fractal Loaded, Novel, and Compact Two- and Eight-Element High Diversity MIMO Antenna for 5G Sub-6 GHz (N77/N78 and N79) and WLAN Applications, Verified with TCM Analysis. Electronics 12 (4), 952 (2023).

Tripathi, S., Mohan, A. & Yadav, S. Performance study of a fractal UWB MIMO antenna for on-body WBAN applications. Analog Integr. Circuits Signal Process. 95, 249–258 (2018).

Rajkumar, S., Anto, A., Amala & Selvan, K. T. Isolation improvement of UWB MIMO antenna utilizing molecule fractal structure. Electron. Lett. 55 (10), 576–579 (2019).

Gurjar, R., Upadhyay, D. K., Kanaujia, B. K. & Kumar, A. A compact modified Sierpinski carpet fractal UWB MIMO antenna with square-shaped funnel-like ground stub. AEU - Int. J. Electron. Commun. 117, 1–10 (2020).

Ez-Zaki, F. et al. Double negative (DNG) Metamaterial-Based Koch fractal MIMO antenna design for Sub-6-GHz V2X communication. IEEE Access. 11, 77620–77635 (2023).

Kamal, M. M. et al. Self-decoupled quad-port CPW-fed fractal MIMO antenna with UWB characteristics, Int. J. Antennas Propag. 1, 3826899 (2024).

Iqbal, Z., Mitha, T. & Pour, M. A Self-Nulling Single-Layer Dual-Mode microstrip patch antenna for grating lobe reduction. IEEE Antennas. Wirel. Propag. Lett. 19 (9), 1506–1510 (2020).

Darimireddy, N. K., Reddy, R. R. & Prasad, A. M. A miniaturized hexagonal-triangular fractal antenna for wideband applications. IEEE Antennas Propag. Mag. 60 (2), 104–110 (2018).

Chaudhary, A. K. & Manohar, M. A modified SWB hexagonal fractal Spatial diversity antenna with high isolation using meander line approach. IEEE Access. 10, 10238–10250 (2022).

Vinoy, K. J., Abraham, J. K. & Varadan, V. K. On the relationship between fractal dimension and the performance of multi-resonant dipole antennas using Koch curves. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 51 (9), 2296–2303 (2003).

Werner, D. H. & Ganguly, S. An overview of fractal antenna engineering research. IEEE Antennas Propag. Mag. 45 (1), 38–57 (2003).

Shailesh, G. et al. Compact UWB MIMO antenna with a modified back reflector and supported by characteristic mode analysis for wireless communication applications. IEEE Access. 12, 187302–187312 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Target detection and positioning aided by reconfigurable surfaces: reflective or holographic?? IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 23 (12), 19215–19230 (2024).

Ren, Z. et al. Ultra-Broadband perfect absorbers based on biomimetic metamaterials with dual coupling gradient resonators. Adv. Mater. 37 (11), 2416314 (2025).

Chen, S. et al. Echoes of fingertip: unveiling POS terminal passwords through Wi-Fi beamforming feedback. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 24 (2), 662–676 (2025).

Huang, X., Zhang, X., Zhou, L., Xu, J. X. & Mao, J. F. Low-Loss Self-Packaged Ka-Band LTCC filter using artificial multimode SIW resonator. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs. 70 (2), 451–455 (2023).

Huang, X., Zhou, L., Xu, J. X., Zhang, X. Y. & Mao, J. F. BCB-Based Thin-Film Ka-Band Quarter-Mode SIW packaged filters with ultrawide stopband and independently controlled TZs. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Tech. 70 (10), 4389–4398 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R66), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

This work was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R66),Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S., G.S. and S.K. conceived and performed simulations, experiment, and drafted the manuscript. D.S. and B.G. conducted the experiment. S., G.S. and N.F.S. analyzed the results. S.K., D.S. and B.G. supervised the overall work and provided funding for the experiments. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shailesh, Srivastava, G., Kumar, S. et al. A common grounded ultra-wideband diversity/MIMO antenna with high inter-element isolation. Sci Rep 15, 27334 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10635-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10635-5