Abstract

The health monitoring of the subsea-immersed tunnels is essential for the early detection of anomalies and the assurance of their long-term operational safety. This research examines sensor data to evaluate variations in critical parameters and their effects on structural integrity. It also compares the efficacy of two deep learning algorithms, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Transformer, in predicting structural conditions. The findings indicate that the Transformer model exhibits high reliability in forecasting and is particularly adept at handling extended periods and intricate time series data, rendering it especially appropriate for health assessments of immersed tube structures. Three correlation analysis techniques are employed to calculate correlation coefficients, thereby identifying the parameters that exert the most significant influence on structural health. The CRITIC method is utilized to assign weights to these parameters. Subsequently, a structural health evaluation model based on the fusion of multi-source information is proposed, facilitating the assessment of the immersed tube’s condition and enabling predictions regarding its status over the subsequent 12 to 24 h. This proactive methodology offers a comprehensive insight into the tunnel health, allowing for implementing preventive measures before the emergence of issues and ultimately reducing maintenance costs. The practical implications of this research are significant, as it provides a robust methodology for the real-time monitoring and evaluation of subsea-immersed tunnels, thereby enhancing their operational safety and reducing maintenance costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid acceleration of global urbanization and the increasing demand for inter-regional transportation, extensive underground infrastructure projects, including subsea tunnels, mountain tunnels, and urban subway systems, are being developed globally. These initiatives facilitate the integration of transportation networks, urban growth, and inter-regional economic development1,2. The Dalian subsea-immersed tunnels represent an advanced example of structural engineering. Nevertheless, the construction environment’s intricate nature, the materials’ prolonged corrosion, and the possibility of natural disasters pose considerable safety challenges3. Evaluating and forecasting the condition of the immersed tube tunnel structure presents a considerable challenge4. Consequently, effective monitoring of the real-time operation of the tunnel and timely implementation of maintenance interventions to deal with the problems are essential to ensure the long-term safety and stability of the tunnel.

During tunnel construction and operation phases, monitoring techniques were predominantly conventional, depending mainly on manual inspections and fundamental instrument measurements5. Manual inspections generally encompass visual evaluations and scheduled localized assessments performed by inspectors. Various instruments, including crack width gauges, displacement meters, and inclinometers, are employed to monitor tunnel deformation, the progression of cracks, and structural displacement6,7. Nevertheless, this approach predominantly depends on manual intervention, which limits its efficiency and effectiveness in accurately monitoring the real-time and overall health status of the tunnel. This is particularly pertinent to long-term concerns, such as material degradation and gradual displacement8. Initial monitoring efforts also utilized essential physical measurement instruments, such as stress-strain gauges and vibration sensors9. These instruments can be strategically positioned at critical points within the tunnel infrastructure to assess local stress-strain, vibration, and temperature metrics10. Nevertheless, these devices frequently function autonomously and possess restricted data collection capabilities, thereby hindering the establishment of a holistic monitoring network. Consequently, they face challenges in fulfilling the requirements of contemporary tunnel engineering for sustained monitoring within intricate environments.

In light of these challenges, the implementation of Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) technology is progressively gaining traction11. SHM technology gathers real-time data about temperature, humidity, stress, displacement, and other essential parameters by strategically placing sensors at pivotal locations within the tunnel. Subsequently, it utilizes sophisticated data analysis methodologies to assess and forecast the structural integrity of tunnel12. The swift advancement of the Internet of Things, sensor technology, and artificial intelligence has significantly enhanced Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) technology in recent years. The integration of high-precision sensors and sophisticated data processing capabilities allows for a more thorough assessment of the structural integrity of tunnels, facilitating the identification of potential structural concerns through the analysis of long-term monitoring data13. Furthermore, using machine learning and deep learning methodologies offers enhanced and precise instruments for forecasting the condition of tunnel infrastructures.

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) is a fundamental model utilized for analyzing time series data, with Hopfield’s circular network being considered the archetype of RNN architecture14. In contrast to feed-forward neural networks, recurrent neural networks (RNNs) integrate a feedback mechanism for the processing of inputs15. Traditional RNN faces challenges related to gradient vanishing when processing extended sequences. To address this issue, Hochreiter proposed the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network, which utilizes gating mechanisms to handle long-term dependencies effectively16,17,18. In 2017, Vaswani introduced the Transformer model, initially developed for natural language processing applications, including machine translation. The Transformer incorporates the Self-Attention Mechanism, which allows the model to allocate different attention weights to various data points, thereby enhancing its ability to capture long-range dependencies more effectively19,20. The Transformer architecture, which exclusively utilizes attention mechanisms while omitting conventional recurrent layers, enables the parallel processing of sequential data, thereby markedly improving computational efficiency21.

This research examines monitoring data from the Dalian subsea immersed tunnels, gathered between August 10 and August 20, 2023, to evaluate the predictive capabilities of LSTM and Transformer models. The study explores the effects of data variability on structural health and seeks to identify the more effective predictive model. Three correlation analysis methods are employed to ascertain the parameters significantly influencing structural health. Furthermore, a multi-source information fusion approach is implemented to construct a health evaluation model for the immersed tube structure, facilitating accurate structural integrity assessments. This approach not only enhances the safety of the tunnels but also prolongs the structure’s service life and minimizes maintenance costs, thereby providing considerable support for future engineering design and maintenance endeavors.

Methodology

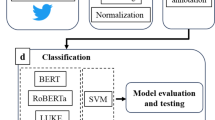

This research aims to ascertain the most appropriate predictive model for the project by evaluating the performance of LSTM and Transformer deep learning algorithms in the context of monitoring data. Correlation analyses employ Pearson, Kendall, and Spearman methods to identify the parameters significantly influencing structural health22,23. The CRITIC method is employed to assign weights to the chosen parameters, facilitating the development of a structural health evaluation model. This model is constructed through a comparative analysis of three fusion techniques: weighting, Kalman, and Bayesian methods. Figure 1 presents the framework of the research.

LSTM method

LSTM is a distinct architecture within the realm of RNN and proficiently mitigates the gradient vanishing issue that frequently occurs in conventional RNNs when handling extended sequences. This is achieved by regulating information flow via three distinct gates: the forget gate, the input gate, and the output gate14. The cell state is central to the LSTM architecture, which is transmitted linearly and modified throughout the network, facilitating efficient information flow. The mechanisms afforded by these three gates enable LSTM to manage the retention adeptly, updating, and output of information, thus effectively capturing long-term dependencies24. Fig. 2 provides a visual representation of the LSTM network structure.

The basic structure of the LSTM neural network25.

The primary function of the forgetting gate is to assess the information in the previous cell state Ct−1 and determine which information to retain and which to discard26. The inputs to the forgetting gate are the hidden layer state information t−1 from the previous time step ht−1 and the current input t at time tx. The expression for the forgetting gate is:

Where \(\:{\text{f}}_{\text{1}}\) is the output of the forgetting gate, \(\sigma\) is the sigmoid activation function, \(\:{\text{W}}_{\text{f}}\) is the weight coefficient of the forgetting gate, \(\:{\text{b}}_{\text{f}}\) is the bias term of the forgetting gate.

The primary function of the input gate is to determine which information should be updated in the cell state27. This process involves two main steps. First, the relevant information is obtained using the sigmoid activation function. Next, the candidate cell state information \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{{\text{C}}_{\text{t}}}\) at the current time \(\:\text{t}\) is derived using the tanh activation function. The specific parameter update formula is as follows:

In this context, ti represents the input gate, while Wi and ib denote the gate’s weight coefficients and bias terms. Similarly, Wc and cb represent the candidate state update layer’s weight coefficients and bias terms. The new cell state information Ct at the current moment is determined by the previous cell state Ct−1 and the candidate cell state information \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{{\text{C}}_{\text{t}}}\) at the current moment. The calculation formula is:

The primary function of the output gate is to regulate the input data and the state from the previous time step, determining which information can be output28. First, the hidden layer state information ht−1 from the previous time step t−1 and the current input xt at time t are processed through the sigmoid activation function to identify which components of the cell state will be output. Then, the output result is multiplied by the cell state, which the tanh activation function has processed to determine the final output. The calculation formula is:

In this context, ot represents the output at the current moment, while Wo and bo denote the weight coefficients and bias terms of the gate, respectively. ht represents the hidden layer state information at the current moment.

Transformer model

The Transformer model utilizes the Self-Attention Mechanism to dynamically allocate weights to each data point while processing sequential information, thereby effectively capturing long-range dependencies29. In contrast to conventional recurrent architectures, the Transformer relies solely on the attention mechanism, which facilitates the parallel processing of sequential data and markedly enhances computational efficiency. Key elements of the model comprise the self-attention layer and the multi-head attention mechanism. The comprehensive structure of the Transformer model is depicted in Fig. 3.

The overall architecture of the Transformer neural network30.

The Self-Attention Mechanism primarily serves to identify the relationships between vectors31. These relationships can be quantified through various operations, including multiplication or dot products, with the dot-product approach being the most prevalent. The specific process involves multiplying a vector by a transformation matrix Wq to obtain vector q and multiplying the related vector by a transformation matrix Wk to produce vector k. The correlation is then determined by taking the dot product of vectors q and k. A higher similarity between the two vectors increases the dot product value. The methodology for assessing vector similarity is outlined as follows:

By repeating the calculation process outlined above, the correlation α1,1, α1,2, α1,3, α1,4 can be obtained. After calculating the values of these four correlations, the attention scores are derived through the softmax layer32. The multi-head attention mechanism improves upon single-head attention by partitioning it into several subspaces, allowing each subspace to identify unique features later combined. This can be articulated as follows:

In this context, [.;.] represents the connection operation, while \(\:{\text{W}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{q}}\) and \(\:{\text{W}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{k}}\) denote the weight matrices that map the input embedding vector to the Query, Key, and Value matrices. Wo refers to the linear transformation of the output, with these weights being trained during the training process.

The training of deep learning models necessitates a meticulous selection of model parameters to attain high-precision predictions33. Key parameters include training duration, prediction step size, the number of model layers, hidden layer size, training epochs, batch size, and learning rate. In the present study, the training sequence length was established at 100, the prediction step size at 10, the number of model layers at 3, the hidden layer size at 64, the number of training epochs at 100, the batch size at 32, and the learning rate at 0.1. The data collection period was extended from August 10 to August 20, with the prediction interval designated for August 20 to August 21.

Data correlation analysis

Three methods of correlation analysis—Pearson, Kendall, and Spearman—are employed to compute the correlation coefficients of the monitoring data. After acquiring all pertinent indicators, the final correlation coefficients are established to assess the relationships among the data sets34. This analytical approach serves to identify the indicators that have a significant influence on the structural health of the tunnel.

The Pearson correlation coefficient measures the linear relationship between two variables, with its values spanning from − 1 to 1. A coefficient approaching 1 denotes a robust positive linear association, whereas a coefficient nearing − 1 indicates a strong negative linear association. A value approximating 0 implies the absence of a significant linear relationship between the two variables. The formula utilized for the computation of the Pearson correlation coefficient is presented as follows:

Where \(\:{\text{x}}_{\text{i}}\) and \(\:{\text{y}}_{\text{i}}\) are the observed values of the two variables, respectively; \(\:\bar{\text{x}}\) and \(\:\bar{\text{y}}\) are the averages of the two variables, respectively; and n represents the number of samples.

The Kendall correlation coefficient quantifies the degree of agreement in rankings between two variables35. Its values span from − 1 to 1, where higher values signify greater consistency. The formula utilized for the computation of the Kendall correlation coefficient is presented as follows:

Where \(\:\text{C}\) is the number of consistent pairs, representing the pairs that have the same ranking order for the two variables; D is the number of inconsistent pairs, representing the pairs that have opposite rankings; T is the number of juxtaposed pairs for variable 1 in the original data; and U is the number of juxtaposed pairs for variable 2 in the original data.

The Pearman correlation coefficient is used to measure the monotonic relationship and rank correlation of the two variables, which is suitable for the data of nonlinear relationships36. The formula is as follows:

where \(\:{\text{d}}_{\text{i}}\) is the difference between the rankings of each pair of samples; n is the number of samples.

By comprehensively utilizing Pearson, Kendall, and Spearman correlation coefficients, the dependencies between the data can be captured at different levels. Combining these three methods effectively addresses outliers and non-normal distributions in the data, compensating for the limitations of any single method.

Multi-source information fusion

CRITIC objective weighting method

The CRITIC method is a well-established objective weighting technique employed in multi-attribute decision-making37. This method is characterized by assessing objective weights derived from two fundamental dimensions of attribute information: the strength of contrast among attributes and the degree of conflict between them. The procedure for calculating weights utilizing the CRITIC method is outlined as follows:

Collect the observation data for each index across different decision objects to construct a decision matrix. The decision matrix X is an m × n matrix, where m represents the number of decision objects, and n represents the number of indicators.

Import the normalized data and calculate the standard deviation \(\:\sigma_{\text{j}}\) of each attribute to evaluate its contrast strength individually.

A symmetric n×n matrix is constructed to represent the linear correlation coefficients between the ith attribute and the jth attribute, denoted as \(\:\rho_{\text{ij}}\).

By combining the standard deviation \(\:\sigma_{\text{j}}\), the information measure contained in each attribute is obtained.

If the value of Gj is significant, it indicates that the jth attribute has a large amount of information, and a larger weight value should be given now.

Weight fusion

Weighted fusion employs the weight of each sensor’s data to compute the final fusion result, denoted as X38. This method is widely used in data fusion due to its simplicity and ease of application compared to more complex algorithms. Furthermore, the final output from weighted fusion is often more reliable and valid.

Where n is the total number of sensor data; i is the sensor data; wi assigns weights to each sensor; xi is the ith column sensor data.

Kalman filter fusion

Kalman fusion is an algorithm designed to estimate the state of dynamic systems39. This algorithm employs a recursive estimation technique specifically tailored for linear dynamic systems, effectively combining the system model with measurement data to yield the most accurate estimate of the system’s state. The Kalman filter operates through two fundamental phases: prediction and update, which forecast and refine the sensor data. In the prediction phase, the state model is utilized to extrapolate the state value for the subsequent time point, while a new state covariance matrix is calculated concurrently.

In the formula, Fk is the state transition matrix, a mathematical model that describes how the state of a dynamic system evolves, illustrating the relationships between state variables. Bk is the control input matrix, while uk represents the input coefficients of the control system state due to external influences. FkTD is the transition matrix of the state transition matrix Fk.

The Kalman update involves calculating the Kalman gain Kk after obtaining the new measurement value. This Kalman gain is then used to update the state estimate \(\:\widehat{{x}_{k}}\), followed by an update to the covariance matrix Pk to refine the uncertainty of the state value.

In the formula, Hk is the matrix of state and measurement; HkT state transition matrix Hk transition matrix; zk is the measured value of the current time step; I is the unit matrix.

Repeatedly executing Kalman prediction and updating operations on each data column’s measured values at every time step, information from multiple sensors is continuously integrated, and the state estimation is updated over time. This process produces a more reliable and accurate estimate. The final fusion result \(\:\widehat{{x}_{f}}\), combined with the weight wi calculated by the CRITIC method, is assigned to the estimated state value \(\:\widehat{{x}_{i}}\) of the ith sensor data.

Bayes data fusion

Bayesian fusion utilizes the weights derived from the CRITIC method as the prior probability P(H)40. To establish the likelihood function P(E|H) for each observed value (original data), we employ data features to fit various probability distributions, including regular, exponential, gamma, and minimum Weibull distributions. The selection of the most suitable distribution is guided by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), which serves as a model selection criterion that effectively balances goodness of fit against model complexity. This makes the AIC particularly useful for evaluating different statistical models’ relative strengths and weaknesses within the same category. We then compute the corresponding probability density function to ascertain each observed value’s edge probability P(E). Finally, by applying Bayes’ theorem, we integrate the edge probability with the prior probability to derive the posterior probability P(H|E), which is subsequently utilized as a new weight for data fusion.

In the formula, k is the number of parameters (degree of freedom) of the model; \(\:\widehat{\text{L}}\) is the log-likelihood value corresponding to the maximum likelihood estimation of the model.

Engineering background and monitoring scheme

The Dalian subsea immersed tunnels project features a main line with a total length of approximately 5,098 m. The project is initiated at No. 20 Planning Road in Suoyu Bay, located on the northern shore, and extends southward along the eastern perimeter of the Suoyu Bay business district. The structure, composed of concrete and steel immersed tubes, traverses Dalian Bay and reaches the southern bank at Dalian Port. Following this, the tunnel shifts eastward, crossing Ganglong West Road, Changhai Road, and Gangwan Bridge, ultimately linking with the surface road on the western side of Renmin Road. As the operational lifespan of the tunnel increases, its infrastructure is subject to progressive deterioration resulting from environmental erosion, load stresses, and natural disasters. Inadequate maintenance of the tunnel could significantly compromise its durability and longevity.

The installation schematic for the health monitoring sensors is illustrated in Fig. 4. Temperature gradient sensors are affixed to the top plate, side walls, and the upper section of the immersed tube. Five fiber grating temperature sensors are systematically distributed along the steel support and the inner side of the primary reinforcement at the outermost extremities. The spacing between the sidewall sensors is approximately 25 cm, while the distance between the sensors on the roof and floor is around 29 cm. A seismic monitoring point is situated on the east side wall of the relevant section of the utility tunnel, positioned 250 mm above the lower partition plate. The seismograph is mounted on an L-bracket, ensuring that the Z-axis (vertical) is oriented upright, the X-axis (horizontal) is aligned parallel to the middle partition wall, and the Y-axis (horizontal transverse) is perpendicular to the sidewall of the middle partition wall of the immersed tube. Furthermore, a temperature and humidity sensor is installed on the side wall at the upper section of the carriageway. Electrochemical-integrated sensors are positioned on the cross-sectional structure’s outer and inner sides, with each group comprising four monitoring points.

Results and analysis

LSTM prediction results

Figure 5 presents the temperature data obtained from five fiber optic grating sensors strategically located along the side wall of the immersed tube segment, designated as 1# through 5# from the interior to the exterior. The temperature measurements recorded between August 10 and 20 exhibited the following ranges: 17.47–18.07 °C for sensor 1#, 16.38–16.97 °C for sensor 2#, 14.78–15.41 °C for sensor 3#, 13.10–13.77 °C for sensor 4#, and 12.60–13.27 °C for sensor 5#. The data reveals a generally stable temperature profile characterized by a slight upward trend and a distinct gradient, indicating a progressive decrease in temperature from the inner to the outer sensors. Sensor 1# recorded the highest temperature, approximately 18 °C, while sensor 5# recorded the lowest, approximately 13 °C. Temperature variations can result in concrete’s thermal expansion and contraction, leading to thermal stress and the potential for micro-cracking. Consequently, long-term temperature monitoring is crucial for evaluating structural changes.

In assessing the integrity of immersed tube structures, the longevity of reinforced concrete emerges as a pivotal consideration. The measurement of polarization resistance indicates the corrosion rate affecting the steel reinforcement; elevated resistance values suggest a corrosion reduction and a more stable protective film on the steel surface. Monitoring variations in polarization resistance is instrumental in the early identification of corrosion, thereby aiding in mitigating potential structural damage. Additionally, dielectric resistance correlates with the concrete’s moisture content and pore structure, indirectly reflecting its density and overall durability. As illustrated in Fig. 6(a), the polarization resistance exhibited fluctuations between 101 and 108 kΩ·cm² from August 10 to 20, signifying mild corrosion activity. Furthermore, Fig. 6(b) indicates a decline in dielectric resistance from 14.75 to 13.25 kΩ·cm², which may be attributed to alterations in the concrete’s pore structure or water migration.

The corrosion rate serves as a direct quantitative measure of steel corrosion, while the corrosion current density indicates the level of corrosion activity, with elevated values signifying increased corrosion intensity. Figure 7(a) presents the temporal variation of the corrosion rate (represented by black squares, ranging from 0.00570 to 0.00605 mm/a) and corrosion current density (depicted by red hollow squares, varying from 0.49 to 0.51 mA/cm²). Both parameters demonstrate analogous fluctuation patterns, implying stable environmental conditions surrounding the immersed tube structure. Figure 7(b) illustrates a gradual decrease in open circuit potential (indicated by gray hollow squares), which shifts from − 0.946 V to −0.956 V, suggesting a slight escalation in the corrosion of the steel bar. Although the observed change of 0.01 V is relatively minor, it warrants consideration in the context of long-term monitoring. The resistivity of the concrete (represented by red solid circles) remains consistent, fluctuating between 30 and 39 kΩ·cm², indicating minimal variation in corrosive factors such as humidity or chloride ion concentration. In Fig. 7(c), the pH level consistently remains elevated (ranging from 12.731 to 12.735), providing adequate protection for the steel bars embedded within the concrete. The concentration of chloride ions remains stable, ranging from 97.45 to 97.53 mg/L; however, the potential for long-term accumulation may still influence the corrosion of the steel.

Figure 8(a) illustrates an upward trend in water pressure during the observation period, with values ranging from approximately − 0.14 kPa to just above 0.04 kPa. Figure 8(b) shows that water temperature fluctuates between 23.5 °C and 29.0 °C, while relative humidity varies from 65 to 95%. Notably, temperature and humidity exhibit an inverse relationship—humidity decreases as temperature rises, and vice versa.

In the context of extreme environmental conditions, such as seismic events or high-velocity winds, it is imperative for structures to possess the capability to endure dynamic loads originating from multiple directions. The analysis of XYZ acceleration data facilitates the identification of potential structural vulnerabilities. Figure 9 illustrates the acceleration data about the immersed tube structure across the X, Y, and Z axes. Specifically, Fig. 9(a)-(c) demonstrate that the peak accelerations across all three axes predominantly cluster around 0.001 ± 0.0005 m/s², with occasional instances of exceeding 0.004 m/s². These findings indicate that the structure maintains a commendable level of stability and seismic resilience in response to typical vibrations and shocks.

Figure 10 presents the displacement data for the immersed tube structure across three distinct axes. The vertical differential displacement (VDD) remains consistent, fluctuating between 79.8 mm and 80.6 mm, which signifies a robust vertical stability. In contrast, the horizontal differential displacement (HDD) shows minor variations, ranging from 71.7 mm to 72.3 mm, indicating a balanced distribution of foundation pressure on both sides of the structure, with no notable lateral displacement observed. Additionally, the axial tension (AT) displacement varies from 56.8 mm to 58.1 mm, reflecting that the structure maintains stable axial tension without experiencing significant tensile or compressive forces.

Transformer prediction results

The findings presented in Sect. 4.1 indicate that the LSTM method yields precise predictions. To conduct a more comprehensive performance assessment, we implemented the Transformer model on the identical monitoring data period and juxtaposed its predictions with those generated by the LSTM. The figure has enlarged the interest section for a more detailed analysis.

Figure 11(a) depicts the corrosion rate over a designated time frame, with the actual data denoted by black squares exhibiting a relatively stable trend. The LSTM model, represented by blue squares, demonstrates accurate predictions during the initial stages; however, it experiences minor discrepancies as time progresses. The Transformer model, illustrated by red solid and hollow circles, reveals two distinct phases: in the initial phase (red solid circles), the predictions closely correspond with the actual data, while in the subsequent phase (red hollow circles), the model effectively extrapolates future trends. Figure 11(b) showcases the predictions of concrete resistivity, where the LSTM model (hollow circles) also performs satisfactorily at the outset but diverges later on. Likewise, the Transformer model (blue triangles and green inverted triangles) displays robust predictive capabilities for future data, as demonstrated by the prediction of pH values presented in Fig. 11(c).

Water stop pressure and structural tube deformation are employed as pivotal variables to enhance the comparative analysis of prediction accuracy between the two models. These elements are essential environmental and dynamic parameters that significantly affect structural health. Figure 12(a) displays the results about water pressure, indicating that the predictions generated by the LSTM model exhibit lower accuracy. Conversely, the Transformer model demonstrates markedly superior performance during the initial phase (as indicated by the green line) and showcases exceptional predictive capabilities in the subsequent phase (represented by the blue line), accurately forecasting future trends. This enhanced performance in predicting water pressure highlights the Transformer model’s proficiency in capturing trends over an extended temporal range, which is crucial for the proactive maintenance and monitoring of immersed tube structures. Such capabilities enable timely interventions to address potential health concerns. Additionally, Fig. 12(b), which depicts the predictions related to tube deformation parameters, further substantiates this assertion, as the Transformer model yields highly accurate predictions.

In conclusion, the LSTM model is proficient in capturing long-term dependencies within time series data and exhibits reliability in predicting tunnel health41. Nonetheless, it may face challenges related to gradient vanishing when dealing with extended sequences42. Conversely, the Transformer model, characterized by its self-attention mechanism, demonstrates superior capability in capturing global information, particularly in high-dimensional datasets43.

Health status of submarine immersed tunnel based on multi-source information fusion

To improve the precision of data correlation analysis, choosing the most suitable correlation coefficient on the specific attributes of the data is crucial. The three principal types of correlation coefficients are Pearson, Kendall, and Spearman. The analytical procedure encompasses several steps: first, importing and examining the data; second, selecting the appropriate correlation coefficient; third, calculating the correlation and performing significance tests; fourth, assessing the independence of the data; and finally, presenting the results. As a case study, we will examine the correlation of the ‘internode E3-E4-D’ data with a portion of the original data displayed in Table 1.

The application of Python for correlating correlation coefficients based on the original data obtained from the internode E3-E4-D measuring point yielded the findings summarized in Table 2. Generally, a correlation coefficient exceeding 0.8 indicates a strong relationship, while a p-value derived from a significance test that is less than 0.05 signifies statistically significant outcomes. In this analysis, all p-values were found to be below 0.05, affirming a high degree of confidence in the results of the data analysis.

The findings indicate that the datasets for VDD and HDD across the tube sections do not adhere to the assumptions of normality. The Kendall correlation coefficient for these variables is 0.5, which suggests a relatively low yet stable correlation; thus, the Kendall coefficient is deemed a more appropriate measure in this context. Conversely, the analysis of VDD and AT between the tube joints also failed the Shapiro-Wilk normality test, resulting in a non-significant p-value. In this case, the Kendall correlation coefficient is −0.2, reflecting a low correlation. Similarly, the data for HDD and AT between the tubes do not conform to a normal distribution. The Spearman correlation coefficient, which is more adept at capturing their monotonic relationship, is 0.2, indicating a low correlation.

In the context of the E3-E4 tubes section, we have successfully conducted a preliminary screening of indicators informed by the correlation analysis detailed in Table 2. The principal aim of multi-source data fusion is to harness the advantages of each data source while mitigating the shortcomings inherent to individual sources, thus improving the quality of data analysis and decision-making processes. Table 3 enumerates the eight indicators identified through the correlation data analysis and their respective weights determined via the CRITIC method.

In the development of the health level assessment criteria, health levels are categorized into four distinct classifications based on predefined parameters: extremely high (IV), high (III), medium (II), and low (I). A higher score indicates a superior health status of the structure. The intervals utilized for the classification of structural health levels are detailed in Table 4.

Table 4 indicates that the data about structural vibration sensors carry the greatest weight in the CRITIC weighting methodology. Consequently, the health index is ultimately weighted using three fusion methods, leading to the development of Table 5, which presents the health ratings for the three health indices corresponding to the three fusion methods employed.

This study further examines the accuracy of the health evaluation model developed through three fusion techniques: weighted fusion, Kalman fusion, and Bayesian fusion. The assessment of the model is conducted from three distinct perspectives: stability, trend, and robustness.

Stability Verification: The stability of the data is evaluated by computing the standard deviation of the outcomes derived from each fusion method, with a lower standard deviation indicating more excellent data stability. Trend Analysis: The trend of the data is determined using a linear regression equation, for which the R-squared value and P-value are calculated. The R-squared value reflects the explanatory power of the trend, while the P-value assesses its statistical significance. Robustness Analysis: To evaluate robustness, random noise is introduced to the data, and the average difference and standard deviation between the original and the noisy data are computed. Minor differences and standard deviations imply that the data or model demonstrates enhanced robustness against noise. Robustness analysis involves the introduction of random noise to the dataset, followed by the computation of the mean difference and standard deviation between the original dataset and the perturbed dataset. A lower mean difference and standard deviation suggest that the data or model exhibits greater robustness when subjected to noise. The accuracy verification results for the evaluations of the three methods are presented in Table 6.

The results show that the structural health level of the subsea tunnel is extremely high within ten days. Finally, the Kalman fusion and Transformer model are selected to predict the data in the next 12–24 h, and the health status of the tunnel in the next 12–24 h is still extremely high (IV).

Discussion

The flowchart of health status of submarine immersed tunnel based on multi-source information fusion is presented in Fig. 13. Figure 13 illustrates the procedure from multi-source sensor data acquisition and preprocessing to correlation analysis, key parameter screening, CRITIC-based weight calculation, multi-method fusion (weight, Kalman, and Bayesian), health level evaluation, and accuracy verification. In the present study, the Transformer model outperforms the LSTM in both short- and long-term predictive tasks; however, its increased computational complexity may present obstacles to practical implementation. Pearson, Kendall, and Spearman correlation analyses were utilized to identify critical parameters influencing tunnel health. These analytical methods enhance the interpretability and accuracy of the model’s predictions, although they may produce slightly divergent results for specific indicators44. Future research endeavors could integrate additional methodologies to substantiate these findings further.

Multimodal fusion has been instrumental in synthesizing environmental and deformation data, thereby facilitating a thorough assessment of tunnel integrity45. Nonetheless, several challenges persist, including the processing of heterogeneous data, the alignment of disparate data sources, and the appropriate weighting of these sources. The discrepancies in time intervals and frequencies among the various data inputs necessitate meticulous attention during preprocessing.

In the current study, the dataset is limited to a 10-day monitoring period (August 10–20, 2023). Although this short-term dataset may not fully capture annual temperature trends, long-term structural degradation, or extreme environmental events (e.g., seismic activity or high-velocity winds), it plays a critical role in validating the feasibility of deep learning models (LSTM and Transformer) for structural health monitoring (SHM) in subsea immersed tunnels46. The high-frequency, multi-sensor measurements (1,440 data points per sensor at 10-minute intervals) demonstrate the ability of these models to process temporal dynamics and multi-source information fusion, providing a foundational methodology for real-time monitoring and short-term predictions (12–24 h ahead, as shown in Table 6).

This process establishes a normal state envelope in which deviations from learned patterns, even in the absence of extreme event data, can indicate potential anomalies. The multi-source fusion capability of these models (as detailed in Table 3) provides a framework for making inferences, in which the smaller earthquake accelerations are used as the reference values for identifying abnormal dynamic responses. This proof-of-concept approach establishes a baseline for SHM applications in complex subsea environments, where long-term data collection encounters technical and cost challenges. The focused dataset enables rigorous evaluation of model performance under typical operational conditions, laying the groundwork for future expansions to longer monitoring periods.

Conclusion

This research utilized LSTM and Transformer models to examine historical data obtained from various parameters, including water temperature, water stop pressure, corrosion rate, and displacement measurements collected by sensors in subsea tunnels. The findings reveal that during the initial phase of prediction, both the LSTM and Transformer models exhibited comparable performance, successfully fitting the actual data. Nevertheless, the Transformer model exhibited a notable degree of consistency in forecasting future data, highlighting its substantial advantages in identifying trends within complex time-series datasets and in extrapolating future values. Consequently, this model is particularly well-suited for predicting the structural integrity of immersed tube structures, which are characterized by extended timeframes and intricate time-series data.

In order to integrate the predictive outcomes from multiple models and maintain consistency in data range and scale, weights are allocated through the process of multi-source data fusion. This approach has led to the establishment of a structural health evaluation model. The results revealed that the health status of the immersed tube structure within the subsea tunnel was classified as ‘extremely high’ during the period from August 10 to August 21.

Data availability

Data is provided within the supplementary information files.

References

Liu, Y. et al. Evolution of the coupling coordination between the marine economy and urban resilience of major coastal cities in China. Mar. Policy. 148, 105456 (2023).

Zhu, H., Yan, J. & Liang, W. Challenges and development prospects of ultra-long and ultra-deep mountain tunnels. Eng 5 (3), 384–392 (2019).

Zhao, K. et al. Stability of immersed tunnel in liquefiable seabed under wave loadings. Tunn. Undergr. Sp Tech. 102, 103449 (2020).

Xiang, Y. & Yang, Y. Challenge in design and construction of submerged floating tunnel and state-of-art. Procedia Eng. 166, 53–60 (2016).

Attard, L. et al. Tunnel inspection using photogrammetric techniques and image processing: A review. ISPRS J. Photogramm Remote Sens. 144, 180–188 (2018).

Huang, H. et al. Inspection equipment study for subway tunnel defects by grey-scale image processing. Adv. Eng. Inf. 32, 188–201 (2017).

Xiang, Y. et al. Dam safety on-site inspection and test. On-site Inspection and Dam Safety Evaluation. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. ; 23–101. (2024).

Jiang, Y. et al. Tunnel lining detection and retrofitting. Autom. Constr. 152, 104881 (2023).

Huang, X. et al. Development and in-situ application of a real-time monitoring system for the interaction between TBM and surrounding rock. Tunn. Undergr. Sp Tech. 81, 187–208 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Stability monitoring of surrounding rock mass on a forked tunnel using both strain gauges and FBG sensors. Meas 153, 107449 (2020).

Negi, P., Kromanis, R., Dorée, A. G. & Wijnberg, K. M. Structural health monitoring of inland navigation structures and ports: a review on developments and challenges. Struct. Health Monit. 23 (1), 605–645 (2024).

Xu, X. et al. A novel vision measurement system for health monitoring of tunnel structures. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 29 (15), 2208–2218 (2022).

Zhou, C. et al. Digital twin for smart metro service platform: evaluating long-term tunnel structural performance. Autom. Constr. 167, 105713 (2024).

Sherstinsky, A. Fundamentals of recurrent neural network (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network. Phys. D. 404, 132306 (2020).

Barak, O. Recurrent neural networks as versatile tools of neuroscience research. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 46, 1–6 (2017).

Su, Y. & Kuo, C. C. J. On extended long short-term memory and dependent bidirectional recurrent neural network. Neurocomputing 356, 151–161 (2019).

Liao, Y., Zhang, R., Zong, Z. & Wu, G. Channel-attention-based LSTM network for modeling temperature-induced responses of cable-stayed bridges. Struct. Health Monit. ; 24 (2), 778-793 (2024).

Liu, C., Pan, J. & Wang, J. An LSTM-based anomaly detection model for the deformation of concrete dams. Struct. Health Monit. 23 (3), 1914–1925 (2024).

Yang, J. et al. Focal attention for long-range interactions in vision Transformers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 30008–30022 (2021).

Wang, R. et al. A novel transformer-based semantic segmentation framework for structural condition assessment. Struct. Health Monit. 23 (2), 1170–1183 (2024).

Reza, S., Ferreira, M. C., Machado, J. J. & Tavares, J. M. R. A multi-head attention-based transformer model for traffic flow forecasting with a comparative analysis to recurrent neural networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 202, 117275 (2022).

Zhang, Y. & Zhu, J. Damage identification for Bridge structures based on correlation of the Bridge dynamic responses under vehicle load. Struct 33, 68–76 (2021).

Zhao, G. et al. Spearman rank correlations analysis of the elemental, mineral concentrations, and mechanical parameters of the lower cambrian Niutitang shale: A case study in the Fenggang block, Northeast Guizhou province, South China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 208, 109550 (2022).

Fathalla, A., Li, K., Salah, A. & Mohamed, M. F. An LSTM-based distributed scheme for data transmission reduction of IoT systems. Neurocomputing 485, 166–180 (2022).

Kembhavi, A. et al. A diagram is worth a dozen images. Comput. Vis. ECCV. 14, 235–251 (2016).

Zhou, G. B., Wu, J., Zhang, C. L. & Zhou, Z. H. Minimal gated unit for recurrent neural networks. Int. J. Autom. Comput. 13 (3), 226–234 (2016).

Landi, F., Baraldi, L., Cornia, M. & Cucchiara, R. Working memory connections for LSTM. Neural Netw. 144, 334–341 (2021).

ArunKumar, K. E., Kalaga, D. V., Kumar, C. M. S., Kawaji, M. & Brenza, T. M. Forecasting of COVID-19 using deep layer recurrent neural networks (RNNs) with gated recurrent units (GRUs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) cells. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 146, 110861 (2021).

Ding, Y. et al. A novel time-frequency transformer based on self-attention mechanism and its application in fault diagnosis of rolling bearings. Mech. Syst. Signal. Process. 168, 108616 (2022).

Su, X. et al. An end-to-end framework for remaining useful life prediction of rolling bearing based on feature pre-extraction mechanism and deep adaptive transformer model. Comput. Ind. Eng. 161, 107531 (2021).

Li, W., Qi, F., Tang, M. & Yu, Z. Bidirectional LSTM with self-attention mechanism and multi-channel features for sentiment classification. Neurocomputing 387, 63–77 (2020).

Geng, Z., Li, J., Han, Y. & Zhang, Y. Novel target attention convolutional neural network for relation classification. Inf. Sci. 597, 24–37 (2022).

Du, Q. et al. Performance prediction and design optimization of turbine blade profile with deep learning method. Energy 254, 124351 (2022).

Li, Z., Gao, X. & Lu, D. Correlation analysis and statistical assessment of early hydration characteristics and compressive strength for multi-composite cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 310, 125260 (2021).

Franceschini, F. & Maisano, D. Aggregating multiple ordinal rankings in engineering design: the best model according to the kendall’s coefficient of concordance. Res. Eng. Des. 32, 91–103 (2021).

Williams, R. M., Alikhademi, K. & Gilbert, J. E. Design of a toolkit for real-time executive function assessment in custom-made virtual experiences and interventions. Int. J. Hum-Comput Stud. 158, 102734 (2022).

Pena, J., Nápoles, G. & Salgueiro, Y. Explicit methods for attribute weighting in multi-attribute decision-making: a review study. Artif. Intell. Rev. 53, 3127–3152 (2020).

Mi, X., Lv, T., Tian, Y. & Kang, B. Multi-sensor data fusion based on soft likelihood functions and OWA aggregation and its application in target recognition system. ISA Trans. 112, 137–149 (2021).

Song, R. & Fang, Y. Vehicle state Estimation for INS/GPS aided by sensors fusion and SCKF-based algorithm. Mech. Syst. Signal. Process. 150, 107315 (2021).

Zamani, M. G. et al. A multi-model data fusion methodology for reservoir water quality based on machine learning algorithms and bayesian maximum entropy. J. Clean. Prod. 416, 137885 (2023).

Tang, L. et al. A Spatiotemporal data mining method for advanced prediction and assessment of large combined excavation-induced wall deformations and risks. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. ; 15 (5), 2758-2777 (2024).

Van Houdt, G., Mosquera, C. & Nápoles, G. A review on the long short-term memory model. Artif. Intell. Rev. 53 (8), 5929–5955 (2020).

Zhang, Q. et al. Transformer-based attention network for stock movement prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 202, 117239 (2022).

Lin, Z., Lim, J. Y. & Oh, J. M. Innovative interpretable AI-guided water quality evaluation with risk adversarial analysis in river streams considering spatial-temporal effects. Environ. Pollut. 350, 124015 (2024).

Dimitri, G. M. et al. Multimodal and multicontrast image fusion via deep generative models. Inf. Fusion. 88, 146–160 (2022).

Xun, X., Zhang, J. & Yuan, Y. Multi-Information fusion based on BIM and intuitionistic fuzzy D-S evidence theory for safety risk assessment of undersea tunnel construction projects. Buildings 12, 1802 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors of this paper express their gratitude to the CCCC Key Laboratory of Port Geotechnical Engineering and the CCCC Key Laboratory of Coastal Engineering Hydrodynamics for their technical support during the experimental research process.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work has been supported by the Science and Technology R&D Project of CCCC First Harbor Engineering Company Ltd (Project No. 2024-8-8).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, Y., Hou, J., Yang, L. et al. Structural health monitoring and evaluation method for an immersed tunnel based on deep learning. Sci Rep 15, 24393 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10643-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10643-5