Abstract

Children with sepsis are at risk of developing life-threatening multiple organ dysfunction (MODS). We have previously described two sepsis phenotypes associated with poor prognosis: “persistent hypoxemia, encephalopathy and shock” (PHES) and “sepsis-associated persistent MODS” (PMODS). We hypothesized there are unique metabolomic and cytokine profiles associated with these phenotypes that will allow for better identification and understanding of their pathophysiology. To test this, plasma samples from 50 children with sepsis-associated MODS were categorized as meeting criteria for PHES, PMODS or assigned as controls. Concentrations of 166 lipids, 26 metabolites and 20 cytokines were measured and analyzed. Of 50 patients, 17 were classified as the PHES phenotype and had upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and an endothelial activation biomarker compared to controls (p < 0.05). 14 patients were classified as PMODS and had significant downregulation of immune mediators compared to controls (p < 0.05). Both phenotypes were associated with mitochondrial dysfunction based on the metabolic profiles of lysine, carnitine, and short and long chain fatty acids. Our results demonstrate metabolomic, immune, and endothelial dysregulation associated with two high-risk sepsis phenotypes in children. If validated, our findings suggest there may be several immune modulation, endothelial repair, and metabolic support therapies that could be tested in these phenotypes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

First described in the 1970s, sepsis-associated MODS is the development of life-threatening, potentially reversible dysfunction of two or more organs due to sepsis1,2. However, targeted treatments for sepsis-associated MODS have remained elusive likely due to the heterogeneity of the syndrome3. We have previously described two high-risk trajectory-based phenotypes of sepsis-associated MODS: persistent hypoxemia, encephalopathy and shock (PHES) and sepsis-associated persistent MODS (PMODS)4,5. The PHES phenotype was derived and validated using a data-driven approach based on the type, severity, and trajectory of six organ dysfunctions in the first 72 h after admission in critically ill children with sepsis. Patients with the PHES phenotype had a higher degree of respiratory and cardiovascular system dysfunction and were less likely to resolve their organ dysfunction by day 3 than other patients with sepsis-associated MODS. When adjusting for confounders, including severity of illness, patients with PHES were independently associated with poor outcomes and were associated with heterogeneity of treatment effect to hydrocortisone and albumin therapy in a propensity score matched analysis4,5. PMODS describes patients who fail to recover their organ function and have persistent MODS on day 7 after diagnosis or die before then. PMODS has been used both as a clinical outcome and a way to characterize a high-risk trajectory of children with sepsis4,5,6,7. Having a better understanding of the underlying pathobiological pathways associated with these trajectory-based phenotypes could inform the development and testing of novel targeted therapies for these high-risk subsets of children with sepsis.

Plasma levels of cytokines, lipids, small metabolites, and other biomarkers could help us elucidate the potential pathobiological mechanisms underlying these phenotypes. Cytokines include chemokines, adipokines, interleukins (IL), interferons (INF), and tumor necrosis factors (TNF), are produced by a broad range of immune cells, and are crucial to the immune response in a wide variety of clinical scenarios including infection, vaccine efficacy, trauma response, and cancer8,9. Lipids are fatty compounds whose functions include energy storage, cell-to-cell signaling, and formation of the structural components of cell membranes. Small metabolites (< 1500 Da) include nucleotides, organic acids, amino acids, peptides, and steroids that perform basic cellular functions such as cellular respiration and cell signaling, as well as carbohydrate, amino acid, and nucleic acid metabolism. Significant changes in these small molecules have been detected in a variety of critical illnesses ranging from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) to septic shock, however plasma metabolomic studies in pediatric sepsis remain limited10,11,12,13,14. Here our aim was to identify and describe plasma metabolic and cytokine derangements within 36 h of PICU admission that are associated with the development of the PHES or PMODS phenotypes. We hypothesized there are different cytokine, lipid and small metabolite profiles early in the admission associated with PMODS and PHES that will allow us to better understand the pathobiology underlying both of these high-risk sepsis phenotypes.

Results

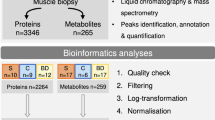

The clinical characteristics for the 50 patients with sepsis-associated MODS stratified by presence of the high-risk phenotype are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age, gender or race/ethnicity, however patients characterized as having either of the high-risk phenotypes were associated with significantly higher pSOFA scores than the other sepsis-associated MODS patients (p < 0.001). Overall, 365 lipids, 43 small molecules and 20 cytokines were assayed. Molecules at or below the level of detection were excluded leaving 166 lipids, 26 metabolites and 20 cytokines for analysis, provided in Supplemental File 1. Data was normalized, log transformed and then scaled prior to analysis.

PHES phenotype vs. controls

Of the 50 patients, 17 (34%) were classified as having the PHES phenotype. The log2 fold-changes of small molecules that were significantly altered in PHES patients as compared to sepsis-associated MODS controls were calculated and graphed (Fig. 1A), with AUC calculated (Fig. 1B) and t-test performed. The significantly altered small molecules included 6 cytokines, 2 metabolites and 19 lipids. The cytokine profile was notable for upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (including Il-8, IL-6, Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein 1 (MCP-1)), as well as endothelial activation (Intracellular Adhesion Molecule (ICAM-1)). MPEA analysis was performed with the KEGG and SMPDB metabolite databases and identified eight dysregulated pathways that included regulation of lysine, carnitine, threonine, 2-Oxobutanoate and short, long, very long and branched chain fatty acids (Fig. 3A,C).

(A) The log2 fold-change in the persistent hypoxemia, encephalopathy, and shock (PHES) phenotype patients as compared to sepsis-associated MODS controls was calculated for each significant small molecule and graphed. (B) The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) was calculated and t-test performed with all significant (p < 0.05) molecules listed.

PMODS vs. other sepsis-associated MODS controls

Of the 50 patients with sepsis-associated MODS, 14 (28%) were categorized as PMODS. We repeated the same analysis in this cohort (Fig. 2A). There were 28 significant molecules identified consisting of 9 cytokines, 1 metabolite and 18 lipids (Fig. 2B). The cytokine profile was notable for lower plasma concentrations in PMODS as compared to controls, including for IFN-ɣ, TNF-⍺, Granulocyte Macrophage Colony Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF), IL-1, IL12p70, IL-4, and IL-13. MPEA analysis identified five dysregulated pathways that included regulation of lysine, carnitine and short and long chain fatty acids (Fig. 3B,D).

(A) The log2 fold-change in the persistent multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (PMODS) phenotype patients as compared to sepsis-associated MODS controls was calculated for each significant small molecule and graphed. (B) The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) was calculated and t-test performed with all significant (p < 0.05) molecules listed.

Metabolic pathway enrichment analysis (MPEA) for patients with persistent hypoxemia, encephalopathy, and shock (PHES) phenotype and persistent multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (PMODS) phenotype. MPEA results for (A) PHES and (B) PMODS using the SMPDB metabolite database with the top 25 results shown. The results of the MPEA for the PHES phenotype (C) and PMODS (D) using both the KEGG and SMPDB databases are shown, listing the significant pathways40,41,42.

PMODS vs. PHES

Of the 50 patients with sepsis-associated MODS, 7 were categorized as only PMODS (not PHES), 10 as only PHES (not PMODS) and 7 as having both PMODS and PHES. We repeated a similar analysis comparing the 7 PMODS only patients to the 10 PHES only patients (supplemental Fig. 2A,C). There were 4 lipids, LPC.18.2, LPC.18.0, LPC.18.1 and LPC.20.3 identified as significantly decreased in PHES compared to PMODS. We also performed a similar analysis that included the patients that met both PHES and PMODS criteria: 14 PMODS patients were compared to 17 PHES patients (supplemental Fig. 2B,D). The lipid LPC.18.2 was the only small molecule identified and was significantly decreased in PHES compared to PMODS. MPEA analysis did not identify any significantly dysregulated pathways for either comparison (data not shown).

Discussion

In our study, we found that the plasma concentrations of cytokines, lipids, and small metabolites in the first 36 h of admission were associated with two high-risk, organ dysfunction-based trajectory phenotypes of pediatric sepsis. Patients with the PHES phenotype were characterized by a pattern consistent with hyperinflammation, endothelial activation, and altered regulation of lysine, carnitine, threonine, and fatty acid metabolism. Patients with PMODS were characterized by lower plasma levels of IFN-ɣ, TNF-⍺, and GM-CSF, consistent with immunoparalysis, as well as altered regulation of lysine, carnitine, and fatty acid metabolism.

We have previously found an association between the PHES phenotype and the hyperinflammation and endothelial activation profile based on IL-8 and ICAM-1 levels15. These results suggest that there’s external validity in our findings in the PHES cytokine analysis. It also suggests that targeted therapies that can help modulate the hyperinflammatory state and endothelial injury may be beneficial in patients at high risk of PHES. We have previously shown that in a propensity score matched analysis, patients with PHES were associated with heterogeneity of treatment effect to hydrocortisone therapy and albumin infusion4, with PHES patients receiving these therapies having improved outcomes when compared to controls, who either had no improvement or had associated harm. Corticosteroids have been used to reduce hyperinflammatory states in sepsis and other critical illnesses with variable success16,17. Similarly, albumin infusions have been shown to help recover the endothelial glycocalyx and may be protective in endothelial injury18,19,20.

This is the first analysis of the metabolic profile of patients with PHES. Prior studies of metabolites in adults with septic shock compared to non-septic controls has demonstrated decreased threonine levels, consistent with our results13,21. However, these studies must be considered with caution, given that many previously published metabolomic studies tend to compare patients with higher severity (e.g., septic shock) to patients with much lower severity (e.g., non-septic or healthy controls). In our analysis, we purposefully compared our high-risk phenotype to other sepsis-associated MODS controls, since this could provide insights related to finding targeted therapies for subsets of these higher risk patients. The metabolism of lysine, carnitine, threonine and fatty acids play important roles in mitochondrial function and energy production. In hepatocyte mitochondria, lysine is degraded into acetyl CoA, a crucial precursor to the energy producing citric acid cycle and produces carnitine as a byproduct. Carnitine, obtained largely through diet, transports fatty acids into the mitochondria where they are oxidized to produce energy. Carnitine not taken in by dietary means can be produced through lysine or methionine breakdown in the kidney, liver and brain22. Cardiac muscle, which has the highest organ concentration of lysine, must obtain it from plasma transportation22. Taken together, the need for increased energy production coupled with mitochondrial dysfunction in PHES may initially lead to lysine breakdown, seen in the increased plasma concentration in the first 36 h. However, as the disease progresses, patients who are unable to maintain carnitine homeostasis may lose cardiovascular metabolic support, one potential mechanism to the hemodynamic instability seen in the PHES phenotype, which is associated with persistent shock as a hallmark of the phenotype. Further, multiple key steps of steroidogenesis occur within the mitochondria, so the suggested mitochondrial dysfunction in PHES patients may also explain the associated heterogeneity of treatment to hydrocortisone therapy. There are other potential targeted therapies that could help modulate the metabolic dysregulation in PHES. Supplementation with L-carnitine has been shown to reduce protein catabolism in severe trauma patients23. However, in a multicenter Phase II clinical trial of septic shock patients randomized to L-carnitine or placebo did not show any differences, possibly due to heterogeneity of treatment effect amongst subsets of patients with sepsis, as suggested by our data24. Finally, low dose caffeine has been shown to increase lipid metabolism and increase mitochondrial turnover in murine hepatocytes and skeletal muscle cells25,26. While this could in theory benefit the energy production pathways in PHES, this therapy has not been tested in patients with sepsis.

Our results suggest that PMODS is in part associated with a global immune dysregulation, including lower plasma levels of IFN-ɣ, TNF-⍺, and GM-CSF, which is consistent with immunoparalysis27,28. Previous studies of children with sepsis-associated MODS have identified immunoparalysis as a critical phenotypes associated with poor outcomes27. Therapies including the administration of GM-CSF have been proposed as a rescue for patients with immunoparalysis and are currently being studied in children29.

Both the PHES and the PMODS phenotypes have significant overlap, with 50% of PHES patients meeting PMODS criteria. Every metabolic pathway identified as significant for PMODS was also identified as significant for PHES, suggesting that the overlapping pathobiological mechanisms of these two phenotypes may be related to mitochondrial function and energy production. As such, some of the possible targeted metabolic therapies discussed, such as L-carnitine, hydrocortisone, and low dose caffeine could also be tested in patients at risk for PMODS4,24,25,26. Four small molecules were identified as significant in both PHES and PMODS: carnitine, PC(34.4), IL12p70 and IL-1. We have previously discussed the possible roles of carnitine and inflammation dysregulation however any potential role of PC(34.4) is much less clear. PC(34:4) is one of many phosphatidylcholines and very little is known about its specific biological role. Research published on it thus far consists solely of metabolomics screens such as in adult non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or Alzheimer’s patients30,31. More is known about phosphatidylcholines in general, which are a type of glycerophospholipid and glycerophospholipids involved in a variety of cellular functions including cell signaling and cell membrane integrity. Here it is unclear what cell signaling pathways or membranes may be disrupted but, interestingly, PC(34.4) levels are increased in both the PMODS and PHES phenotypes, which taken together with the dysregulation of other lipids in our data may be reflective of high cellular membrane turnover or remodeling.

Due to the overlap between the results for PMODS and PHES we performed an analysis comparing the two directly to try to identify small molecules that can differentiate these two phenotypes early in admission. Only one small molecule, the lipid LPC.18.0 was identified as significant when patients with PHES were compared to PMODS, however when patients with both PHES and PMODS were excluded and the analysis repeated, four lipids LPC.18.2, LPC.18.0, LPC.18.1 and LPC.20.3 were significantly decreased in PHES patients. There were no significantly dysregulated pathways by MPEA using either comparison. The low number of molecules identified and lack of pathways identified is most likely due to the lower number of total patients for analysis as well and the overlap between the phenotypes. We can only speculate on what the lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) family of lipids may play in these phenotypes. LPCs have been shown to play a pro-inflammatory role including cytokine secretion, leukocyte migration and stimulation of multiple neutrophil functions32,33,34,35. Here, when we compare PHES to PMODS, the relative level of LPCs was decreased, suggesting that the reduced level of LPCs is correlated with less severity within the PHES phenotype (i.e. those 10 patients did not develop PMODS). This would seem contradictory to prior studies of septic adults which have shown that a lower level of LPC or a reduced ratio of LPCs to PCs both correlate with worsening mortality36,37. Indeed exogenous administration of LPC into a mouse model of sepsis protected them from mortality38. It is difficult to compare our study to these prior works as we don’t have healthy control patients for comparison so we cannot say whether the LPC levels in PHES patients are decreased (relative to healthy) or simply less increased than PMODS patients. Regardless, we believe the identification of LPCs in our study in the PHES and PMODS phenotypes is consistent with the hypothesis that the severity of these phenotypes is in part due to global dysregulation of the immune response.

Our study has several limitations. This was a single-center study with a limited sample size and our findings must be externally validated. While our population size of 50 is similar to previously published metabolomics studies, our findings can only be considered preliminary and hypothesis-generating. Additionally, we only studied a subset of all possible cytokines and metabolites and only took samples within the first 36 h of admission for pragmatic reasons. Future studies with a larger sample size and multiple time points could benefit from untargeted metabolomic and proteomic analyses and follow identified metabolic derangements over time to help further understand the role of these molecules such as the LPCs and the immune response and inform optimal timing of any proposed therapeutic interventions.

In conclusion, we found that the plasma concentrations of cytokines, lipids, and small metabolites early in the admission are associated with two high-risk trajectory-based phenotypes of pediatric sepsis, PHES and PMODS. Our results suggest that the severity of both PHES and PMODS may be due to dysregulation of mitochondrial production of energy, that the PHES phenotype is also associated with hyperinflammation and endothelial activation, and that the PMODS phenotype is associated with global immune dysregulation consistent with immunoparalysis. If our findings are validated, there are several immune modulation, endothelial repair, and metabolic support therapies that could be tested in patients with these high-risk sepsis phenotypes in future studies.

Methods

This study is a retrospective analysis of plasma samples taken from children who were admitted with sepsis-associated MODS to a single-center pediatric intensive care unit between 6/2018 and 11/2019.

Sample collection and storage

We analyzed plasma sample for 50 patients that were collected within 36 h of admission to the PICU as part of a prospective biorepository study for children with MODS in the PICU. Patients were approached for consent if they were infants with an adjusted gestational age of 38 weeks or more and minimum weight of 3 kg or up to 17 years of age. Informed consent was provided from parents and written assent provided from patients between 12 and 17 years of age. The biorepository study was approved by the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago Institutional Review Board (IRB #2018 − 1630) and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Samples aliquoted, stored at -80 C and later thawed for the metabolomic analysis in this study. There were no other freeze-thaw cycles. For this current study we only included the subset of samples of patients who met sepsis-associated MODS criteria, which we defined as having a confirmed or suspected infection based on the use of microbiological testing and antimicrobial therapy on admission to the PICU and having associated MODS. MODS was defined as having a Pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (pSOFA) score of 2 or more in 2 or more organs, as previously done.4.

Phenotype classification

We classified patients as having PHES phenotype based on the pattern of organ dysfunction within the first 72 h of ICU stay using a previously validated method using a random forest classifier39. PMODS phenotype was assigned based on the persistence of MODS by day 7 after admission or death within 7 days5.

Metabolite concentration profiling

Plasma samples were processed using the Biocrates AbsoluteIDQ® p400 HR kit (Biocrates Inc., Aliso Viejo CA) utilizing standard procedures as dictated by the manufacturer. Quantification of 365 lipids and 43 small molecules was then performed by high resolution accurate-mass mass spectrometry (HRMS) at Northwestern University’s Metabolomics Core. Metabolites were excluded from analysis if the only quantified values were at or below the minimum level of detection. Plasma levels of 192 small molecules including 166 lipids and 26 metabolites were remaining for analysis.

Cytokine profiling

Cytokine levels were measured using mean fluorescence intensity with the Luminex Inflammation 20-Plex Human ProcartaPlex Panel (ThermoFischer Scientific, Waltham MA) using standard procedures as dictated by the manufacturer and run in duplicate with the mean value analyzed. Wells with coefficients of variance greater than 20% were excluded.

Statistical modeling

To account for high and low abundancy metabolites data was preprocessed using previously published metabolomics methods with normalization by median, log transformation and mean-center scaling.12 We used the MetaboAnalyst 6.0 software to perform a univariate analysis of the differences in metabolite levels comparing patients with one of the phenotypes to the remaining sepsis-associated MODS patients without the give phenotype. We then generated and calculated the area under the receiver operating curves (AUC) for the sets of significant metabolites. To assess for dysregulated metabolic pathways, metabolic pathway enrichment analysis (MPEA) was performed and compared to first the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genome (KEGG) and then the Small Molecule Pathway Database (SMPDB) human metabolite databases using previously published methods40,41,42,43. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The raw data utilized for analysis in this paper as well as the associated population demographics are provided as Supplemental Fig. 1.

References

Baue, A. E. Multiple, progressive, or sequential systems failure. A syndrome of the 1970s. Arch. Surg. 110, 779–781. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1975.01360130011001 (1975).

Seymour, C. W. et al. Derivation, validation, and potential treatment implications of novel clinical phenotypes for Sepsis. JAMA 321, 2003–2017. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.5791 (2019).

DeMerle, K. M. et al. Sepsis subclasses: A framework for development and interpretation. Crit. Care Med. 49, 748–759. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000004842 (2021).

Sanchez-Pinto, L. N. et al. Derivation, validation, and clinical relevance of a pediatric Sepsis phenotype with persistent hypoxemia, encephalopathy, and shock. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 24, 795–806. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000003292 (2023).

Sanchez-Pinto, L. N., Stroup, E. K., Pendergrast, T., Pinto, N. & Luo, Y. Derivation and validation of novel phenotypes of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome in critically ill children. JAMA Netw. Open. 3, e209271. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9271 (2020).

Wong, H. R. et al. Combining prognostic and predictive enrichment strategies to identify children with septic shock responsive to corticosteroids. Crit. Care Med. 44, e1000–1003. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001833 (2016).

Atreya, M. R. et al. Machine learning-driven identification of the gene-expression signature associated with a persistent multiple organ dysfunction trajectory in critical illness. EBioMedicine 99, 104938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104938 (2024).

Kany, S., Vollrath, J. T. & Relja, B. Cytokines in inflammatory disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20236008 (2019).

Dinarello, C. A. Historical insights into cytokines. Eur. J. Immunol. 37 (Suppl 1), 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.200737772 (2007).

Hall, M. W. et al. Monocyte mRNA phenotype and adverse outcomes from pediatric multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Pediatr. Res. 62, 597–603. https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181559774 (2007).

Jaurila, H. et al. (1)H NMR based metabolomics in human sepsis and healthy serum. Metabolites 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo10020070 (2020).

Grunwell, J. R. et al. Cluster analysis and profiling of airway fluid metabolites in pediatric acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Sci. Rep. 11, 23019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02354-4 (2021).

Mickiewicz, B. et al. Integration of metabolic and inflammatory mediator profiles as a potential prognostic approach for septic shock in the intensive care unit. Crit. Care. 19, 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-014-0729-0 (2015).

Lin, S. et al. Explore potential plasma biomarkers of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) using GC-MS metabolomics analysis. Clin. Biochem. 66, 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2019.02.009 (2019).

Atreya, M. R. et al. Biomarker assessment of a High-Risk, Data-Driven pediatric Sepsis phenotype characterized by persistent hypoxemia, encephalopathy, and shock. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000003499 (2024).

Marik, P. E. Critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency. Chest 135, 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-1149 (2009).

Rochwerg, B. et al. Corticosteroids in sepsis: an updated systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Crit. Care Med. 46, 1411–1420. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000003262 (2018).

Aldecoa, C., Llau, J. V., Nuvials, X. & Artigas, A. Role of albumin in the preservation of endothelial glycocalyx integrity and the microcirculation: a review. Ann. Intensive Care. 10, 85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-020-00697-1 (2020).

Hariri, G. et al. Albumin infusion improves endothelial function in septic shock patients: a pilot study. Intensive Care Med. 44, 669–671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-018-5075-2 (2018).

Delaney, A. P., Dan, A., McCaffrey, J. & Finfer, S. The role of albumin as a resuscitation fluid for patients with sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care Med. 39, 386–391. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181ffe217 (2011).

Thooft, A. et al. Serum metabolomic profiles in critically ill patients with shock on admission to the intensive care unit. Metabolites 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo13040523 (2023).

Flanagan, J. L., Simmons, P. A., Vehige, J., Willcox, M. D. & Garrett, Q. Role of carnitine in disease. Nutr. Metab. (Lond). 7, 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-7-30 (2010).

Biolo, G., 52S-57S. & et al Metabolic response to injury and sepsis: changes in protein metabolism. Nutrition 13 https://doi.org/10.1016/s0899-9007(97)00206-2 (1997).

Jones, A. E. et al. Effect of levocarnitine vs placebo as an adjunctive treatment for septic shock: the rapid administration of carnitine in Sepsis (RACE) randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 1, e186076. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6076 (2018).

Sinha, R. A. et al. Caffeine stimulates hepatic lipid metabolism by the autophagy-lysosomal pathway in mice. Hepatology 59, 1366–1380. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26667 (2014).

Enyart, D. S. et al. Low-dose caffeine administration increases fatty acid utilization and mitochondrial turnover in C2C12 skeletal myotubes. Physiol. Rep. 8, e14340. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.14340 (2020).

Carcillo, J. A. et al. A multicenter network assessment of three inflammation phenotypes in pediatric Sepsis-Induced multiple organ failure. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 20, 1137–1146. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000002105 (2019).

Hall, M. W., Greathouse, K. C., Thakkar, R. K., Sribnick, E. A. & Muszynski, J. A. Immunoparalysis in pediatric critical care. Pediatr. Clin. North. Am. 64, 1089–1102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2017.06.008 (2017).

VanBuren, J. M. et al. The design of nested adaptive clinical trials of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome children in a single study. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 24, e635–e646. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000003332 (2023).

Bertran, L. et al. LC/MS-Based untargeted metabolomics study in women with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis associated with morbid obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24129789 (2023).

Klavins, K. et al. The ratio of phosphatidylcholines to lysophosphatidylcholines in plasma differentiates healthy controls from patients with alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. (Amst). 1, 295–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dadm.2015.05.003 (2015).

Liu-Wu, Y., Hurt-Camejo, E. & Wiklund, O. Lysophosphatidylcholine induces the production of IL-1beta by human monocytes. Atherosclerosis 137, 351–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9150(97)00295-5 (1998).

Radu, C. G., Yang, L. V., Riedinger, M. & Au, M. Witte, O. N. T cell chemotaxis to lysophosphatidylcholine through the G2A receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 101, 245–250. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2536801100 (2004).

Silliman, C. C. et al. Lysophosphatidylcholines prime the NADPH oxidase and stimulate multiple neutrophil functions through changes in cytosolic calcium. J. Leukoc. Biol. 73, 511–524. https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.0402179 (2003).

Spangelo, B. L. & Jarvis, W. D. Lysophosphatidylcholine stimulates interleukin-6 release from rat anterior pituitary cells in vitro. Endocrinology 137, 4419–4426. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo.137.10.8828503 (1996).

Drobnik, W. et al. Plasma ceramide and lysophosphatidylcholine inversely correlate with mortality in sepsis patients. J. Lipid Res. 44, 754–761. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.M200401-JLR200 (2003).

Park, D. W. et al. Impact of serial measurements of lysophosphatidylcholine on 28-day mortality prediction in patients admitted to the intensive care unit with severe sepsis or septic shock. J. Crit. Care. 29, 882 e885–e811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.05.003 (2014).

Yan, J. J. et al. Therapeutic effects of lysophosphatidylcholine in experimental sepsis. Nat. Med. 10, 161–167. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm989 (2004).

Atreya, M. R. et al. Biomarker assessment of a High-Risk, Data-Driven pediatric Sepsis phenotype characterized by persistent hypoxemia, encephalopathy, and shock. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 25, 512–517. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000003499 (2024).

Kanehisa, M. Toward Understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–D677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Pang, Z. et al. MetaboAnalyst 6.0: towards a unified platform for metabolomics data processing, analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae253 (2024).

Funding

This work was supported by grant RO1HD113685 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child and Human Development to Dr. Sanchez-Pinto.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.R.H. performed data analysis, interpretation of data, wrote the main manuscript text and prepared the tables and figures. L.N.S-P. was responsible for conception and design of the project, acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation of data and revising the figures and article. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was provided from parents and written assent was provided from patients if they were between 12 and 17 years of age.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hurtado, R.R., Sanchez-Pinto, L.N. Metabolomic and cytokine profiles of high-risk sepsis phenotypes in children. Sci Rep 15, 25639 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10665-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10665-z