Abstract

Numerous tunnels are often sited in shallow depths and sloping strata due to topographic and geomorphological constraints, however, the evolutionary mechanisms of slip surfaces and instability patterns under asymmetric loading remain unclear. On the basis of the Terzaghi failure hypothesis and the logarithmic spiral failure mode of shallow tunnels in slope areas, combined with the nonlinear failure criterion of soil and the upper bound theorem of limit analysis, this study proposes a new calculation formula for the surrounding rock pressure of shallow tunnels in slope areas considering slope top loads. By using the SQP algorithm in MATLAB software to optimize the solution, this study elucidated and analyzed the effects of the slope top load, buried depth ratio, initial cohesion and axial tensile stress on the surrounding rock pressure and failure mode of shallow buried tunnel. This analysis revealed that when the nonlinear coefficient of rock and soil increases and the ratio of the horizontal support reaction force to the vertical support reaction force decreases, the surrounding rock pressure under the logarithmic spiral failure mode of shallow buried tunnel increases. The increase of initial cohesion will lead to the reduction of surrounding rock pressure. The stability of the surrounding rock pressure of shallow buried tunnel decreases with increasing slope top load, buried depth ratio and axial tensile stress. With the increase of the load on the top of the slope and the buried depth ratio, the failure of the shallow tunnel deflects toward the shallow side of the slope. The research findings provide crucial guidance for ensuring safe construction practices in shallow-buried tunnels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

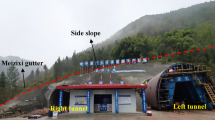

As China’s infrastructure construction has advanced, the development of mountain railways and highways has steadily expanded into the central and western regions. The terrain in the central and western regions is characterized primarily by mountains and hills, with highly complex and variable geological conditions. Asymmetrical terrain and complex geological factors can engender discrepancies in the load distributions on both sides of tunnel structures, leading to the development of biased-load tunnels1,2,3,4,5,6. Additionally, environmental protection constraints and other considerations frequently force tunnel sites to be chosen in areas with shallow burial depths and significant weathering. Compared with tunnels without biased loads, more adverse conditions are faced by biased-load tunnels, which results in more complex structural forces, greater risks, and consequently, increased construction difficulty and costs. As a result, the stability of the surrounding rock in shallowly buried biased-load tunnels remains a central and challenging concern in tunnel design and construction planning7,8,9,10.

In the past several decades, numerous domestic and international scholars have conducted extensive research on these issues. Atkinson et al.11 investigated the stability of shallow tunnels in non-cohesive soils using model tests and the upper- and lower-bound limit analysis methods. Li Tao et al.12 derived explicit solutions for the ultimate support forces and failure surfaces of shallow buried bias tunnels using the Hoek-Brown criterion and upper bound theorem to reveal the influence of key parameters on support forces. In contrast, Li Chuan Wang et al.13 established failure modes of the biased tunnels via limit analysis but did not propose a unified theoretical framework, relying on numerical simulations and empirical corrections, highlighting the limitations of early-stage research in parameterized modeling for complex geological conditions. Zhao Lianheng et al.14 introduced a nonlinear failure criterion via the “initial tangent method” under the upper-bound method, which yields one of many upper-bound solutions. Under certain conditions, this method can produce more realistic upper-bound solutions. However, as the nonlinear parameter (m) increases, the error grows significantly. In comparison, the “external tangent method” offers greater practicality and accuracy. The surrounding rock pressure decreases as the parameters GSI, mi, and σci in the nonlinear Hoek-Brown criterion increase. The optimization process was detailed, and comparisons were made with the standard method, followed by parameter analysis of influencing factors. Increasing the horizontal support effectively reduces the tunnel crown pressure and enhances tunnel stability. The vertical average surrounding rock pressure rises with increasing clear distance, and there is a nonlinear relationship exhibit between these two variables. Extensive experimental data and engineering practices have demonstrated that most rock and soil materials adhere to nonlinear failure criteria. Nonlinear strength is a critical property of rock and soil materials, which has considerable impact on geomechanics and engineering applications15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22.

Existing limit analysis methods for tunnel stability have problems like unreasonable model simplification and parameter determination difficulties under complex conditions such as shallow burial and bias pressure. Using nonlinear failure criteria can accurately reflect the true stress state of tunnels and improve the reliability of calculation results23,24,25,26,27. Chen et al.28 proposed a pioneering framework integrating the nonlinear Mohr-Coulomb failure criterion with a 3D rotational failure mechanism to evaluate critical support pressure in shield tunnel faces under pore water pressure, employing mesh discretization optimization to validate the influence of the nonlinearity coefficient on failure morphology. Cheng and Zeng et al.29 developed an asymmetric progressive collapse mechanism for shallow tunnels in inclined strata using the Hoek-Brown yield criterion and variational principles, deriving closed-form solutions for collapse-block geometry and gravity, and demonstrating the dominant role of the stratum dip angle in collapse asymmetry. Hunan University researchers30 advanced an upper-bound analytical model for surrounding rock pressure under nonlinear failure criteria, although it does not involve the analysis of multiphysical field coupling effects such as seepage-damage. Vrakas31 established a semi-analytical elastoplastic ground response model for tunnels under nonlinear Mohr failure criteria, achieving rigorous closed-form solutions for the Hoek-Brown case, with validation through large-deformation case studies of weak phyllites.

Research on rigid block failure modes using the traditional upper-bound limit analysis method is well-established. However, studies on the logarithmic spiral failure mode for shallow tunnels, accounting for surface inclination and slope-top loading under nonlinear rock and soil failure criteria, remain insufficient32,33,34,35. To add to previous research, this study considers surface inclination and slope-top loading on the basis of the logarithmic spiral failure mode of shallow tunnels, using the upper-bound limit analysis method36 combined with the nonlinear failure criterion from the tangent method. The upper limit of surrounding rock pressure was calculated using the sequential quadratic programming algorithm in MATLAB. Additionally, by adjusting parameters, a comparative analysis was conducted to evaluate the influence of slope-top load and depth-to-width ratio on this failure mode, which will provide practical guidance for engineering applications.

Nonlinear damage criterion

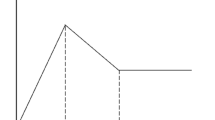

Extensive experimental data and engineering practices have shown that most rock and soil materials adhere to nonlinear failure criteria (Fig. 1). The non-linear M-C criterion has been validated by case studies for cohesive soils such as clays and weathered rocks and non-cohesive materials such as sands and gravels, but intact hard rocks require the Hoek-Brown or anisotropic criterion.

According to reference37, the nonlinear M-C criterion for soil can be expressed as:

In the equation, \(\tau\)denotes the shear stress on the failure surface, \({c_0}\)stands for the initial cohesion, \({\sigma _n}\)represents the normal stress on the failure surface, \({\sigma _t}\)indicates the axial tensile stress, and m is the nonlinear coefficient. The value of m controls the curvature of the curve, to align with engineering practices and validate the model’s sensitivity, we selected m = 1.0 ~ 1.4 based on typical values for weathered strata in slope areas29,38. When m ≠ 1, the tangent equation for Eq. (1) is as follows:

In this equation, \({c_t}\)represents the intercept of the tangent Eq. (2), while \({\varphi _t}\)is the slope of the tangent Eq. (2), which can be derived from the slope calculation formula.

By solving Eqs. (1), (2), and (3) simultaneously, we obtain:

.

Based on the tangent method principle36, the upper-bound solution derived from ct and φt is guaranteed to be the upper-bound solution of the nonlinear Eq. (1).

Destructive mode and velocity field

This study draws on Terzaghi’s failure mode assumption for calculating the surrounding rock pressure in loose rock masses, simplifying the tunnel cross-section to a rectangle, taking into account surface inclination and slope-top load, and neglecting the dilation effect of rock and soil materials. A logarithmic spiral failure mode and its velocity vector diagram for shallow buried biased-load tunnels were constructed (Figs. 2 and 3).

Assuming that the rigid body ABOGO’B’A’A (Fig. 3) moves at a velocity of v0 (v0 = 1.0), according to the velocity field closure condition and the sine theorem, the following equation is obtained:

Surrounding rock pressure calculation

External force power

The formula for calculating the external force power is as follows:

In this equation, e = K∙q; K represents the ratio of horizontal to vertical support forces necessary to maintain the stability of the surrounding rock in the sloped tunnel section.

Internal energy consumption

The formula for internal energy consumption is as follows:

Surrounding rock pressure

Based on the virtual power principle, internal energy dissipation equals the external work done, leading to the derivation of the surrounding rock pressure calculation formula for the logarithmic spiral failure mode in shallow buried tunnels:

Optimum calculation

Since the limit of Eq. (31) must be solved by continuously adjusting the values of (α, β, η, θ, α′, β′, θ′, η′), and the angles between the velocity vectors in Fig. 3 must fall within the required (0, π) range, the values of (α, β, η, θ, α′, β′, θ′, η′) must meet certain constraints. After rearranging, the following is obtained:

Under the constraints of Eq. (32), the optimization process for solving Eq. (31) proceeds by first setting an initial vector in the program, and then continuously adjusting the initial vector (α, β, η, θ, α′, β′, θ′, η′). The optimization computation yields the maximum q value, which represents the upper bound solution for the surrounding rock pressure in the stability limit state of the logarithmic spiral failure mode. The above process can be achieved using the built-in optimization toolbox in MATLAB software. For detailed steps, refer to the Fmincon function section in reference35, and this will not be further discussed here.

Results

Comparative analysis with existing results

To verify the reliability of the above-mentioned logarithmic spiral failure mode calculation method, the parameters for a shallow tunnel in a sloped region were set as follows: burial depth H = 20 m, rectangular tunnel height h = 10 m, span b = 10 m, unit weight of the surrounding rock γ = 20 kN/m³, uniaxial tensile strength σt = 30 kPa, cohesion of surrounding rock c = 10 kPa, internal friction angle φ = 18°, slope surface angle δ = 18°, slope-top load p = 0 kPa, horizontal-to-vertical support force ratio K = 1.0, and nonlinear coefficients m = 1.0, 1.1, 1.2, and 1.4. To facilitate comparative analysis, the internal friction angle φc of the surrounding rock and the friction angle θ on both sides of the roof soil column were selected based on the standard values of the physical and mechanical properties of surrounding rock grades in reference38, with φc = 30°~40° for VI-grade surrounding rock and θ = 0.5φc. The results from various calculation methods are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 shows that the surrounding rock pressure calculated by different methods ranks are as follows: recommended standard method > Terzaghi limit equilibrium method > upper-bound limit analysis method. In comparison, the normative recommended method yields the most conservative results due to its generalized safety factors and linear assumptions, making it suitable for conventional tunnel engineering projects with relatively homogeneous geological conditions and high safety factor requirements. The Terzaghi limit equilibrium method, grounded in the theory of granular media and assuming failure surfaces as vertical slices or logarithmic spirals, is applicable for stability analysis of shallow tunnels in loose strata. The upper-bound limit analysis method, on the other hand, is tailored for tunnels under complex boundary conditions (e.g., slopes or asymmetric loading) and nonlinear material behaviors. Its advantages lie in economic efficiency and the ability to quantify safety parameters, providing a balanced approach for scenarios demanding both precision and cost-effectiveness. Comparative analysis of the upper-bound solution for surrounding rock pressure under different failure modes indicates that the upper-bound solution remains relatively unaffected by variations in failure modes. For m = 1.0, under the linear Mohr-Coulomb failure criterion, the surrounding rock pressure (q) calculated by this method aligns closely with the results in references38,39, verifying the method’s accuracy and reliability. Given that the surrounding rock pressure (q) increases with the nonlinear coefficient (m), simplifying the nonlinear strength criteria of rock and soil materials to a linear assumption in shallow tunnel engineering could severely underestimate the necessary support force, risking severe engineering failure. The surrounding rock pressure (q), which is calculated via both the upper-bound limit analysis and Terzaghi’s limit equilibrium methods, decreases as the K (K0) value increases. Therefore, reducing sidewall support during shallow tunnel construction will increase the surrounding rock pressure, consequently undermining the overall stability of the tunnel.

Exemple analysis

Effect of the slope top load

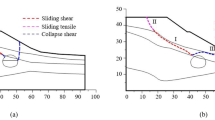

The parameters for the shallow buried tunnel in the sloped section are as follows: burial depth H = 20 m, rectangular tunnel height h = 10 m, span b = 10 m, surrounding rock unit weight \(\gamma\)= 20 kN/m³, uniaxial tensile strength \({\sigma _{\text{t}}}\)= 30 kPa, surrounding rock cohesion\({c_0}\) = 10 kPa, internal friction angle\(\varphi\) = 18°, slope inclination\(\delta\) = 18°, horizontal-to-vertical support force ratio K = 1.0, and nonlinear coefficients m = 1.0, 1.1, 1.2, and 1.4. With slope-top load p ranging from 0 to 200 kPa, the variations in surrounding rock pressure and failure mode are illustrated in Figs. 4 and 5.

As Fig. 4 shows, with all other parameters constant, the magnitude of the slope-top load is significantly positively correlated with the required support force to maintain the stability of the surrounding rock in shallow tunnels. The larger the slope-top load is, the more detrimental it is to the stability of the tunnel’s surrounding rock, and this effect becomes more pronounced as the nonlinear coefficient (m) increases. A typical case analysis indicates that as the slope-top load increases from 0 kPa to 200 kPa, the surrounding rock pressure changes by 16.9–32.7%. This suggests that loads such as vehicular traffic, equipment, and building loads on the tunnel surface will negatively impact the stability of the surrounding rock, therefore, engineering activities in the tunnel-top area should be regulated. Figure 5 reveals that as the slope-top load increases, the tunnel failure mode shifts toward the side with shallower burial depth, making it essential to focus on providing adequate support to that side.

Effect of buried depth ratio

The parameters for the shallow buried tunnel in the sloped section are as follows: tunnel height h = 10 m, span b = 10 m, surrounding rock unit weight\(\gamma\) = 20 kN/m³, uniaxial tensile strength\({\sigma _{\text{t}}}\) = 30 kPa, surrounding rock cohesion\({c_0}\) = 10 kPa, internal friction angle \(\varphi\)= 18°, slope inclination\(\delta\) = 18°, horizontal-to-vertical support force ratio K = 1.0, nonlinear coefficients m = 1.0, 1.1, 1.2, and 1.4, and slope-top load p = 100 kPa. With the burial depth ratio (tunnel burial depth to height ratio) H/h ranging from 1.0 to 2.0, the variations in the surrounding rock pressure and failure mode are shown in Figs. 6 and 7.

Figure 6 shows that, with all other parameters constant, increasing the burial depth ratio leads to an increase in the surrounding rock pressure for shallow tunnels in sloped regions. This effect becomes even more significant as the nonlinear coefficient (m) increases. A typical case analysis indicates that as the burial depth ratio increases from 1.0 to 2.0, the surrounding rock pressure changes by 19.2–30.3%. This suggests that once the tunnel cross-section is determined, tunnel stability can be enhanced by either reducing the burial depth or improving rock and soil stability through grouting to adjust the nonlinear coefficient. Figure 7 reveals that as the burial depth ratio increases, the failure surface of the shallow tunnel shifts toward the shallower side of the slope. Thus, in practical engineering, preemptive reinforcement measures on the shallower side of the slope can mitigate potential risks resulting from this failure surface shift.

Effect of initial cohesion

The parameters for the shallow buried tunnel in the sloped section are as follows: burial depth H = 20 m, rectangular tunnel height h = 10 m, span b = 10 m, surrounding rock unit weight \(\gamma\)= 20 kN/m³, uniaxial tensile strength \({\sigma _{\text{t}}}\)= 30 kPa, surrounding rock cohesion \({c_0}\)= 7 ~ 15 kPa, internal friction angle \(\varphi\)= 18°, slope inclination \(\delta\)= 18°, horizontal-to-vertical support force ratio K = 1.0, nonlinear coefficients m = 1.0, 1.1, 1.2, and 1.4, and slope-top load p = 100 kPa. The variations in the surrounding rock pressure and failure mode are illustrated in Figs. 8 and 9, respectively.

Figure 8 shows that with a constant nonlinear coefficient (m), the surrounding rock pressure decreases significantly as the initial cohesion increases. Conversely, when initial cohesion\({c_0}\)remains constant, the surrounding rock pressure increases noticeably with a higher nonlinear coefficient (m). This suggests that the surrounding rock pressure calculated by the nonlinear criterion is highly sensitive to changes in cohesion\({c_0}\). According to the virtual work principle, as cohesion increases, internal energy consumption rises, thus reducing the required support force for the surrounding rock. Figure 9 reveals that as the initial cohesion\({c_0}\)decreases, the failure surface expands outward significantly, increasing the shear zone area of the logarithmic spiral. Thus, when the surrounding rock conditions are poor, tunnel cross-section construction is more likely to lead to the development of a large plastic zone. Reinforcement methods such as shotcrete, anchors, and grouting can be used to protect shallow buried biased-load tunnels.

Effect of axial tensile stress

The parameters for the shallow buried tunnel in the sloped region are as follows: burial depth H = 20 m, rectangular tunnel height h = 10 m, span b = 10 m, surrounding rock unit weight \(\gamma\)= 20 kN/m³, cohesion of surrounding rock \({c_0}\)= 30 kPa, axial tensile stress \({\sigma _{\text{t}}}\)= 30–70 kPa, internal friction angle \(\varphi\)= 18°, slope surface inclination \(\delta\)= 18°, horizontal-to-vertical support force ratio K = 1.0, nonlinear coefficients m = 1.0, 1.1, 1.2, 1.4, and slope-top load p = 100 kPa. The variations in the surrounding rock pressure and failure mode are illustrated in Figs. 10 and 11.

Figure 10 shows that as the axial tensile stress increases, the surrounding rock pressure increases significantly. The greater the axial tensile stress is, the greater the nonlinear coefficient amplification effect. Figure 11 reveals that with increasing axial tensile stress, the failure surface clearly expands outward, enlarging the shear zone of the logarithmic spiral. This suggests that the plastic zone induced by biased loading during excavation will grow. Thus, axial tensile stress greatly affects both the magnitude of the surrounding rock pressure and the location of the failure surface. For weak surrounding rocks, preemptive engineering support is crucial to prevent collapses caused by inadequate support.

Conclusions

This study focuses on the evolutionary mechanisms of slip surfaces and instability patterns under asymmetric static loading. On the basis of the nonlinear failure criterion of soil and the upper bound theorem of limit analysis, this study elucidated and analyzed the effects of the typical parameters on the surrounding rock pressure and failure mode of shallow buried tunnel. Future work should integrate seepage-damage coupling and dilatancy effects, particularly for tunnels in saturated or high-stress zones. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

The surrounding rock pressure calculated using the recommended standard method is the highest, followed by Terzaghi’s limit equilibrium method, with the upper-bound limit analysis method yielding the lowest pressure. Under the linear Mohr-Coulomb failure criterion, the surrounding rock pressure (q) computed by this method aligns closely with those in references38] and [39, demonstrating its rationality and validity. Therefore, when support systems are designed for shallow buried tunnels in sloped regions under the logarithmic spiral failure mode, the upper-bound limit analysis method is more economical, whereas the recommended standard method is more conservative and costlier.

-

(2)

The surrounding rock pressure for shallow buried tunnels in sloped regions under the logarithmic spiral failure mode increases with the nonlinear coefficient (m) of the rock and soil. The larger the m value is, the greater its impact. Simplifying the nonlinear failure criterion to a linear one severely underestimates the upper bound surrounding rock pressure. Additionally, reducing the horizontal-to-vertical support force ratio (K) significantly increases surrounding rock pressure.

-

(3)

An increase in slope-top load and burial depth ratio has a more significant impact on the soil on the shallower side of the slope than on the deeper side, causing the logarithmic spiral failure mode to shift toward the shallower side. In practical engineering, preemptive reinforcement of the shallower side of the rock and soil is advisable to avoid accidents resulting from this shift.

-

(4)

Increased axial tensile stress or initial cohesion causes outward expansion of the failure surface, enlarging the shear zone of the logarithmic spiral. A higher axial tensile stress increases the surrounding rock pressure, whereas a higher initial cohesion reduces it. Under poor surrounding rock conditions, tunnel cross-section construction is prone to creating large plastic zones, which can be mitigated through support measures such as shotcrete, anchoring, and grouting.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Li, T. & Chen, G. Analysis of factors influencing anti-slip pile support in tunnel landslide systems for tunnels with different burial depths. Transp. Geotechnics. 42, 101079–101098 (2023).

Tian, X. X. et al. Study on progressive failure mode of surrounding rock of shallow buried bias tunnel considering strain-softening characteristics. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 9608–9608 (2024).

Cui, L. et al. Improved Equations of Ground Pressure for Shallow large-diameter Shield Tunnel Considering Multiple Impact Factors138 (Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology incorporating Trenchless Technology Research, 2023).

Liu, Q. W. et al. Primary support optimization of large-span and shallow buried hard rock tunnels based on the active support concept. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 7918–7918 (2022).

Liang, J. Y. et al. Upper bound analysis of asymmetric collapse mechanism of shallow tunnel under seismic load. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 41 (S1), 2772–2779 (2022).

Tian, X. X. et al. Deformation and Mechanical Characteristics of tunnel-slope Systems with Existing anti-slide Piles Under the Replacement Structure of pile-wall153105995–153105995 (Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology incorporating Trenchless Technology Research, 2024).

Guo, D. S. et al. Coupling analysis of tunnel construction risk in complex geology and construction factors. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 148(9), 4022097.1–4022097.13 (2022).

Morovatdar, A., Palassi, M. & Ashtiani, S. R. Effect of pipe characteristics in umbrella arch method on controlling tunneling-induced settlements in soft grounds. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 12 (prepublish), 984–1000 (2020).

Zhou, X., He, Y., Zhang, W. & Liu, D. Multifractal Characteristics and Displacement Prediction of Deformation on Tunnel Portal Slope of Shallow Buried Tunnel Adjacent To Important Structures141662 (Buildings, 2024).

Yuan, B.X., et al. Sustainability of the polymer SH reinforced recycled granite residual soil: properties, physicochemical mechanism and applications. J. Soils Sedim. 23(1), 246–262 (2022).

Atkinson, J. H. & Potts, D. M. Stability of shallow tunnel in cohesionless soil. Géotechnique 27 (2), 203–215 (1977).

Li, T. et al. Upper bound analysis of surrounding rock pressure in shallow buried unsymmetrical tunnels based on the Hoke-Brown criterion. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 46 (2), 3799–3809 (2024).

Wang, C. L., Peng, M. L. & Zhou, W. D. Calculation methods of surrounding rock pressure for small clear spacing shallow unsymmetrically loading tunnel. Adv. Mater. Res. 1601 (430–432), 1464–1467 (2012).

Zhao, L. H. et al. Discussion on generalized tangential method led in nonlinear failure criterion in upper boundary limit analysis. J. Changjiang River Sci. Res. Inst. 27 (8), 34–39 (2010).

Lade, P. V. Elasto-plastic stress-strain theory for cohesionless soil with curved yield surfaces. Int. J. Solids Struct. 13 (11), 1019–1035 (1977).

Hoek, E. & Brown, E. T. Empirical strength criterion for rock masses. J. Geotech. Eng. Div. 106 (9), 1013–1035 (1980).

Donald, I. B. & Chen, Z. Y. Slope stability analysis by the upper bound approach: fundamentals and methods. Can. Geotech. J. 34 (6), 853–862 (1997).

Yang, X. L. & Yin, J. H. Slope stability analysis with nonlinear failure criterion. J. En-gineering Mech. ASCE. 130 (3), 267–273 (2004).

Yu, L., Lyu, C. & Wang, M. Three-dimensional upper bound limit analysis of deep soil tunnels based on nonlinear Mohr-Coulomb criterion. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 41 (6), 1023–1030 (2019).

Wang, S. et al. An anisotropic unified nonlinear strength criterion (AUNS) for geomaterials. Eur. J. Environ. Civil Eng. 24 (14), 2512–2533 (2020).

Chen, W. F. Limit Analysis and Soil Plasticity 3rd edn (J. Ross Publishing, Inc., 2007).

Luo, W. et al. Stability analysis of the surrounding rock of shallow Bias tunnels under aSlope crest load. Mod. Tunn. Technol. 53 (5), 56–62 (2016).

Yang, Z. H., Li, Y. X. & Xu, J. S. Upper bound limit analysis of deep tunnel face support pressure with nonlinear failure criterion under. Pore Water Conditions Build. 14 (9), 2677–2677 (2024).

Yang, X. & Long, J. P. Reliability prediction of tunnel roof with a nonlinear failure criterion. Mathematics 11 (4), 937–937 (2023).

Rodolfo, C. & Javier, V. Nonlinear criterion for strength mobilization in brittle failure of rock and its extension to the tunnel scale. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 32 (4), 685–705 (2022).

Li, D. J. et al. Active stability analysis of 3D shallow tunnel face with longitudinally inclined ground surface based on nonlinear Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion. Int. J. Geomech. 20(11), 4020198.1–4020198.12 (2020).

Chen, G. H., Zou, J. F. & Qian, Z. H. Analysis of tunnel face stability with non-linear failure criterion under the pore water pressure. Eur. J. Environ. Civil Eng. 26 (7), 1–13 (2020).

Chen, L. & Zeng, Z. Q. Upper bound limit analysis of unsymmetrical progressive collapse of shallow tunnels in inclined rock stratum. Comput. Geotech. 103199.1–103199.12 (2019).

Zhang, D. B. et al. Upper bound solution of surrounding rock pressure of shallow tunnel under nonlinear failure criterion. J. Cent. South. Univ. 26 (07), 1696–1705 (2019).

Vrakas, A. A finite strain solution for the elastoplastic ground response curve in tunnelling: rocks with non-linear failure envelopes. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Meth. Geomech. 41 (7), 1077–1090 (2017).

Qian, W. F. et al. Experimental study of face passive failure features of a shallow shield tunnel in coastal backfill sand. Front. Struct. Civil Eng. 18 (2), 252–271 (2024).

Zhang, Z. Q. et al. Failure modes and face instability of shallow tunnels under soft grounds. Int. J. Damage Mech. 28 (4), 566–589 (2019).

Wang, Z. W. et al. Upper Bound Limit Analysis of Support Pressures of Shallow Tunnels in Layered Jointed Rock Strata43171–43183 (Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology incorporating Trenchless Technology Research, 2014).

Yuan, B. X. et al. Eco-efficient recycling of engineering muck for manufacturing low-carbon geopolymers assessed through LCA: exploring the impact of synthesis conditions on performance. Acta Geotech. 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-024-02395-9 (2024).

Tang, G. P. et al. Inclined slices method for limit analysis of slope stability with nonlinear failure criterion. Rock. Soil. Mech. 36 (7), 2063–2072 (2015).

Xue, S. MATLAB Basic Tutorial (Tsinghua University, 2015).

Yuan, B. X. et al. Experimental study on influencing factors associated with a new tunnel waterproofing for improved impermeability. J. Test. Eval. 52 (1), 344–363 (2024).

Yang, F. & Yang, J. S. Limit analysis method for determination of Earth pressure on shallow tunnel. Eng. Mech. 25 (7), 179–184 (2008).

Yang, X. L. & Wang, Z. W. Limit analysis of Earth pressure on shallow tunnel usingnonlinear failure criterion. J. Cent. South. Univ. (Science Technology). 41 (1), 299–302 (2010).

JTG 3370. 1–2018, Specifications for Design of Highway Tunnels Sect. 1 Civil Engineering.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by Project (52268063, 52108320), supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China; Project (20224BAB204063), supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province; Project (2021H0042), supported by the Science and Technology Project of the Jiangxi Provincial Transportation Department; and Project (YC2023-S461), supported by the Special Funding Program for Graduate Student Innovation in Jiangxi Province.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, W.L.; methodology, W.L. and S.L.; software, Z.T.; validation, W.L. and S.L.; formal analysis, S.L. and Z.T.; investigation, X.G. and H.W.; resources, W.L.; data curation, X.G. and H.W.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L. and Z.T.; writing—review and editing, S.L.; visualization, Z.T.; supervision, W.L. and X.G.; project administration and funding acquisition, W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, W., Liu, S., Tao, Z. et al. Nonlinear energy consumption analysis of shallow-buried bias tunnel stability with improvement of failure mode. Sci Rep 15, 25965 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10755-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10755-y