Abstract

As the use of insect growth regulators such as triflumuron becomes more prevalent in modern agriculture, concerns have emerged regarding their multifaceted toxicity in non-target species. In this study, the multifaceted toxicity of triflumuron insecticide in the non-target bioindicator organism Allium cepa L. was investigated. For this purpose, the physiological effects of triflumuron on A. cepa bulbs (germination percentage, weight gain, and root elongation) were screened. In addition, cytogenetic (chromosomal abnormalities = CAs, micronucleus = MN, mitotic index = MI, and DNA damage = Comet analysis) and biochemical (superoxide dismutase = SOD and catalase = CAT enzyme activities, malondialdehyde = MDA and proline accumulation, and chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b amounts) analyses were performed in A. cepa root tip cells exposed to triflumuron. Root tip meristematic cell damage was also among the parameters examined. Onion bulbs were divided into 4 groups. The control group was treated with tap water. The other 3 groups were treated with 1.6 µg/L triflumuron, 10.0 µg/L triflumuron and 24.2 µg/L triflumuron, respectively. The selected triflumuron doses were based on LC₅₀ values reported for aquatic and terrestrial organisms to reflect environmentally relevant exposure levels. The application period lasted 72 h for root development and 144 h for leaf growth required for chlorophyll analysis. Triflumuron insecticide significantly reduced germination, root elongation, and weight gain in all groups. The decline in the values of physiological parameters was exacerbated with increasing dose of triflumuron. Triflumuron administration increased the frequency of MN and CAs, and decreased MI. CAs induced in the triflumuron-exposed groups were ranked according to their frequency as sticky chromosome, fragment, vagrant chromosome, unequal distribution of chromatin and bridge. Comet assay showed a considerable increase in the percentage of tail DNA. Genotoxicity arising from triflumuron was found to be dose-dependent. Triflumuron caused a significant increase in MDA and proline levels and antioxidant enzyme activities and a significant decrease in chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b levels in direct proportion to the application concentration. In the control group, A. cepa root tip meristem cells were normal and healthy. Meristem cell damage, cortex cell damage, cortex cell wall thickening, and flattened cell nuclei were observed in A. cepa root cells treated with triflumuron insecticide. In conclusion, triflumuron is a toxic chemical to A. cepa and toxicity is both multifaceted and tends to increase with increasing doses of triflumuron.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the global population is projected to exceed 10 billion by 2050, the primary objective of producers and researchers is to increase food production to meet the rising demand1. Pesticides are chemical agents employed in agriculture to mitigate the population of pests, thereby enhancing agricultural productivity, income, and nutritional security. These compounds contribute to the sustainability of food production, promote public health, facilitate the cultivation of diverse crops, prolong life expectancies, reduce expenditures related to veterinary and medical care, and prevent soil erosion and moisture loss2,3. The excessive utilization of pesticides, which offer numerous benefits to their users in agricultural production, poses a significant threat to air quality, water resources, and soil health4. Additionally, it causes damage to substance cycles and non-target organisms5. Pesticides, particularly when utilized in a manner that diverges from established standards and precautions, can undergo metabolic processes, bioaccumulate, or be stored and excreted by the human body6. These processes can lead to the development of various health complications, including cancer, diabetes, and nephropathies, as well as cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, and autoimmune abnormalities7.

Triflumuron (2-chloro-N-[[[[4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenyl]amino]carbonyl]benzamide), commercially known as Starycide 480 SC, is an insecticide belonging to the class of “insect growth regulators” and acts as an inhibitor of chitin synthesis in insects8. Chitin synthesis inhibitors are classified as benzoyl phenyl urea family compounds, a chemical group that was first identified during the 1970s9. These inhibitors have been shown to induce deformations in the larval cuticle, thereby rendering insects more vulnerable to pathogens and deformities10. In addition to inhibition of insect molting and pupation, another effect of chitin synthesis inhibitors is the impairment of fertility and egg viability11. Molecularly, triflumuron exerts its function by impeding the incorporation of N-acetylglucosamine during chitin biosynthesis. This inhibition is characterized by suppression of N-acetylglucosamine transport across the epithelial membrane12. Since its discovery by Bayer, triflumuron, an odorless, white and lipophilic powder, has been used to protect crops such as tomatoes, apples, cotton, fruits, vegetables, forest trees, and livestock such as sheep, chickens, and horses against a range of insects belonging to the orders Diptera, Orthoptera, Siphonaptera, Coleoptera, and Lepidoptera8,13,14. Triflumuron is distinguished by its broad-spectrum activity, prolonged efficacy, minimal dosage requirements, low toxicity, and reduced environmental impact15. However, it should be noted that some pesticides, despite their relatively low toxicity, have the potential to induce severe effects in living organisms if utilized excessively, irregularly, or if they undergo continuous accumulation on agricultural crops16.

Bioindicators are organisms, parts of organisms, or communities of organisms that mirror varying degrees of environmental pollution within natural ecosystems or in controlled laboratory settings17. Higher plants have been identified as significant bioindicator organisms for several reasons. They are relatively simple and cost-effective to cultivate. Their chromosomal organization is similar to that of humans because they are eukaryotes. Furthermore, pollutants cannot be applied directly to humans due to ethnic, logistical, and practical considerations17,18. Allium cepa, which belongs to the Amaryllidaceae plant family, serves as a bioindicator plant. In addition, it possesses a large and small number of chromosomes (2n = 16) that are readily identifiable, enabling the assessment of the cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of chemical substances19. Other major advantages of the Allium test are its capacity to proceed without ethical approval and the utilization of straightforward cultivation methods20.

While there are a few studies in the existing literature on triflumuron-induced oxidative stress and genotoxicity in non-target organisms10,21,22there is an absence of a comprehensive study that addresses triflumuron-related toxicity from a multifaceted perspective. The objective of this study was to examine the toxicity of triflumuron in the non-target bioindicator organism A. cepa L. To develop a comprehensive understanding of the toxic effects of triflumuron, a series of physiological, genotoxic, and biochemical analyses were conducted on A. cepa. Additionally, the damage to meristematic cells of roots exposed to triflumuron was investigated.

Materials and methods

Materials

A. cepa L. (2n = 16) bulbs obtained from local commercial markets in Giresun province of Türkiye were utilized in the study. The bulbs were transferred to the laboratory and meticulously cleaned by removing the dry, brown outer leaves and then the dried adventitious roots. Four groups were formed, with bulbs of approximately similar size, as illustrated in Table 1.

The stock chemical from Merck with CAS No. 64628-44-0 was used for the triflumuron solutions preparation. In determining triflumuron doses, concentrations of LC50 for aquatic and terrestrial organisms were taken.

Experimental setup

The bulbs were positioned in the tubes and contacted with the solutions through their reduced stem during the treatment, which was carried out at room temperature. The treatment with the solutions was conducted for 72 h to allow for the emergence of new adventitious roots, and approximately 144 h to initiate the process of leaf development for the purpose of chlorophyll analysis. The solutions were replenished daily to circumvent concentration disparities. After the experimental period, root and leaf samples were harvested, thoroughly washed, and dried.

Analyses of physiological metrics

The physiological effects of triflumuron insecticide were investigated by examining three parameters: germination percentage (%), weight gain (g), and root elongation (cm)23.

The equation (Eq. 1) of Atik et al.24 was used to determine the impact of triflumuron exposure on the germination percentages of A. cepa bulbs on fifty bulbs from each group (n = 50). The percent of germination mentioned in this equation is the emergence of new adventitious roots from the stems of bulbs that have had their old roots shaved off.

Using a digital compass, the roots of ten bulbs chosen randomly from each group were measured to determine the root elongation (n = 10).

Ten bulbs were weighed using a precision scale (n = 10) before and after application to assess weight gain.

Analyses of cytogenetic metrics

The roots were meticulously decontaminated with distilled water to eliminate residual chemicals before the examination of the effects of triflumuron on cytogenetic impacts. The same procedures were employed to calculate the MI value, CAs frequency, and MN frequency25. The roots were segmented into approximately 1 cm long pieces, which were subsequently fixed in a Clarke solution for two hours. The Clarke solution was composed of ethanol (three volumes) and glacial acetic acid (one volume). A 1 N HCl solution was used for hydrolysis of root tips. The hydrolysis was accomplished in a water bath maintained at 62 °C for 13 min. The hydrolyzed materials were then subjected to a cleansing process with glacial acetic acid at a concentration of 45%. After this process, the samples underwent a 16-hour protocol involving staining with 1% acetocarmine. The squashing technique was employed to prepare the slides, which were photographed under a microscope (IRMECO IM-450 TI) with 500x magnification26. For cytogenetic analysis, 10 slides were prepared for each experimental group (n = 10). 1,000 cells, selected randomly from these slides, were examined for the presence of MNs and CAs. The MI was calculated over 10,000 cells which were analyzed from random fields of the slides (Eq. 2).

[MC: mitotic cells, TC: Total cells].

During the MN analysis, three critical factors were given full consideration. The MN must possess a diameter nearly one-third the diameter of the main nucleus. Furthermore, the staining color of the MN and the main nucleus should match. Finally, there must be a clear separation between the MN and main nucleus, even when they seem to touch27.

Determination of DNA damage: comet method

The DNA of A. cepa root tip cells was extracted by the protocol of Sharma et al.28. The progression of the Comet method was based on the approach described by Dikilitaş and Koçyiğit29. The slides intended for use in the Comet test were subjected to a sterilization process involving the application of ethyl alcohol for one day. The slides were then dried in an oven. An aliquot of 100 µl of 1% normal-melting-point agarose, dissolved in distilled water at 50 °C, was spread on the slides. The initial layer was thus formed and subsequently frozen by placing the slides in the refrigerator for 5 min. A second layer was established by overlaying 100 µL of 1% low-melting-point agarose (7/8), mixed with a freshly isolated cell suspension (1/8), on the initial layer. The mixture was maintained at 40 °C, and the slide containing it was promptly covered with a coverslip. Subsequently, the preparations underwent a cooling period in the refrigerator for 5 min. Thereafter, the coverslips were meticulously detached. To dissolve the DNA, the preparations were incubated for 40 min in an electrophoresis tank filled with buffer solution. The electrophoresis lasted 20 min (86 V/cm, 20 V, 300 mA). The preparations were cleaned three times for 5 min each using 0.4 M Tris-HCl for neutralization. Subsequently, 100 µL of ethidium bromide with a concentration of 0.2 mg/mL was utilized for the staining of the slides. Photographic documentation of the stained slides was obtained through a fluorescence microscope. Next, the documents were analyzed through the software “TriTek 2.0.0.38 Automatic Comet Assay” with 1,000 cells per group. The analysis of DNA segments was conducted in two distinct segments: the “head” and the “tail.” DNA concentration in both segments was expressed as percentages (%). The proportion of DNA in the tail was carefully considered as a sign of DNA damage to estimate the extent of destruction30.

Analyses of biochemical metrics

To determine the activities of SOD and CAT, a methodical extraction process was employed to obtain the enzymes from root tip cells, as previously outlined in the extant literature31. To conduct the extraction, root tip segments, each weighing 0.5 g, were crushed in mortars containing 5 mL of ice-cold sodium phosphate buffer. The pH was set to 7.8 and the concentration was 50 mM. A centrifugation procedure was then performed on the homogenates for 20 min at 10,500 g. Thereafter, the upper layer, known as the “supernatant phase,” was collected and stored within a refrigerated environment at a temperature of 4 °C.

To determine SOD activity, 1.5 mL sodium phosphate buffer, 0.01 mL enzyme extract, 0.3 mL EDTA-Na2, 0.3 mL nitroblue tetrazolium chloride (NBT), 0.3 mL methionine, 0.3 mL riboflavin, 0.01 mL insoluble polyvinylpyrrolidone and 0.28 mL distilled water were included in a total volume of 3 mL reaction medium. Following the placement of the mixture into sterile test tubes, it was left at room temperature and subjected to 15 W of fluorescent light. 10 min later, the tubes were placed in a dark chamber to stop the enzymatic reaction. At a wavelength of 560 nm, the absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically to record the color change32. The quantity of SOD inducing a 50% suppression in the reduction of NBT was presented as U/mg fresh weight (FW).

About 2.8 mL reaction medium including 1.5 mL monosodium phosphate buffer, 0.3 mL hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and 1.0 mL distilled water was prepared to assay CAT activity. The addition of 0.2 mL of enzyme extract resulted in the consumption of H2O2 using enzyme catalysis. A spectrophotometric measurement of the absorbance at 240 nm wavelength was employed to record the decrease of H2O2 in the medium brought on by the enzyme activity. The activity was presented as OD240nm min/g FW33.

The determination of MDA level was initiated by homogenizing 0.5 g segments cut from root tips in 1 mL trichloroacetic acid solution (5%) Unyayar et al.34. Centrifugation at a speed of 12,000 g for 10 min was utilized to separate the upper layer of the mixture. An equal volume of 0.5% thiobarbituric acid was mixed with this upper layer in a new tube. The mixture was subsequently placed in a water bath at 96 °C and incubated for 30 min in a 20% trichloroacetic acid solution. The reaction in the tubes was halted in an ice bath. Next, the tubes were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 5 min. The absorbance of the upper phase was measured spectrophotometrically at 532 nm. The MDA level was presented as µM/g FW.

The determination of free proline levels was initiated by homogenizing 0.5 g segments cut from root tips in 10 mL sulfosalicylic acid (3% aqueous). A fresh tube was filled with 2 mL of the homogenate that had been filtered through filter paper, 2 mL of acid-ninhydrin and 2 mL of glacial acetic acid. The tubes were initially left to react in a water bath at 100 °C for 1 h, after which they were cooled in an ice bath to stop the reaction. 4 mL of toluene was added to the medium. Following a 20-second vortexing period, the tubes were subjected to spectrophotometric analysis at a wavelength of 520 nm. This analysis was performed to determine the absorbance of the toluene chromophore, which had been separated from the aqueous layer. The standard graph was prepared with proline as a guide, the proline concentration was calculated by the following formula (Eq. 3).

The extraction process of chlorophyll pigments was initiated by harvesting 0.2 g of the sample from the green leaves of the onions. The sample was then placed in 5 mL of 80% acetone for 1 week to dissolve the pigments. This process needed to be conducted under conditions of 4 °C and darkness. The remaining pigments dissolved by a method of crushing the leaves with a glass baguette was employed. Acetone evaporation was prevented during this process. The separation of the supernatant was achieved through a filtration process, followed by a centrifugation step at 3000 rpm. After adding 5 mL of 80% acetone to the supernatant, centrifugation was performed at the same rpm. The absorbance of the final supernatant was read at two different wavelengths (645 nm and 663 nm)35 to calculate the pigment concentrations using the following equations (Eq. 4 and Eq. 5)36.

A645: the absorbance at 645 nm wavelength, A663: the absorbance at 663 nm wavelength, V: the final volume of acetone with the supernatant, W: the weight of the sample.

Analysis of meristematic tissue disorders

To ascertain the abnormalities, present within the meristematic tissue, cross-sections were obtained from the roots. The sections were placed on a slide and a solution of methylene blue was used for staining the tissues. The solution consisted of a 5% concentration of methylene blue, and the slides were left in the staining solution for 2 min. The coverslipped preparations were imaged at 500x magnification on an Irmeco IM-450 TI research microscope equipped with a camera attachment37.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were presented in tabular form as mean ± standard deviation (SD). One-way ANOVA and Duncan tests were applied to these data to perform the necessary statistical evaluation. This evaluation was conducted using the SPSS Statistics 22 (IBM SPSS) program. The statistical difference between the means was considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Results and discussion

As demonstrated in Table 2, the alterations in physiological toxicity parameters induced by triflumuron insecticide were outlined. In the control group, 100% of bulbs successfully germinated. The germination percentages of the TFM 1, TFM 2, and TFM 3 groups exhibited a decline of 13%, 28%, and 43%, respectively compared to the control group. In this case, the germination rate of bulbs demonstrated a negative relationship with increasing application doses of triflumuron insecticide. Similarly, the results showed that root elongation and weight gain of A. cepa bulbs treated with triflumuron also decreased as the concentration of triflumuron in the solution increased. The differences between the final root lengths and weight gains of these groups were statistically significant compared to both their control values and the values of other treatment groups (p < 0.05). The mean root lengths of the TFM 1, TFM 2, and TFM 3 groups exhibited a decrease of 17.1%, 35.8%, and 67.6%, respectively compared to the control group. Concurrently, the weight gains of these groups demonstrated a reduction of 31.7%, 61.3%, and 73.2%, respectively about to the control group.

According to the extant literature, there is a paucity of studies that demonstrate the effects of pesticides on plants. However, these chemicals have been identified as harmful to plant physiology38. Indeed, pesticides severely affect various physiological processes at different stages of plant life, including cell development, photosynthesis, biosynthesis, and molecular responses, when used above the permissible limit. Poor germination and delayed growth are visible morphological symptoms frequently employed to assess the impact of pesticide use on plants39. For instance, malathion, an insecticide, inhibits the germination process in Triticum aestivum40. In addition, the excessive and uncontrolled use of the insecticide pyriproxyfen, a triflumuron-like insect growth regulator, was found to reduce the germination and radicle length of non-target maize plants, depending on the applied dose of the chemical41. Similarly, elevated levels of imidacloprid and thiamethoxam insecticides have been observed to result in a decline in chickpea germination42. A different study demonstrated that fenitrothion insecticide application suppressed seed germination and early seedling development in soybean43. Endosulfan and chlorpyrifos insecticides inhibited root and stem growth in sorghum and mung bean, respectively44.

Saladin and Clément38 posited that in the development and characterization of pesticides, these chemicals should exhibit no toxicity to non-target organisms, including humans. It has been stated that when a plant is stressed by pesticides, it directs the synthesis of metabolites involved in defense mechanisms at the expense of disrupting its growth to spend nutrients and energy sparingly45. The observed restriction in germination can be attributed to various factors, including the inhibition of reserve substances necessary for germination, impaired protein metabolism, or suppression of hydrolytic enzymes43. Onuminya and Eze46 reported that the suppression of root elongation is an obvious indicator of cytotoxicity and that growth inhibition may result from a disturbance of the balance between promoters and inhibitors of endogenous growth regulators. Roots represent one of the initial interfaces with which plants are exposed to pesticides. Consequently, the application of triflumuron insecticide directly to the environment where roots will develop results in a reduction in root growth. It is imperative to recognize that root growth encompasses more than mere cell proliferation. It is contingent on the enzymes activation that facilitate elongation and the dissolution of the cell wall during the differentiation process47. In the present scenario, the inhibition of water and mineral transport, the reduction in cell division, and structural defects in root cells may also contribute to the insecticide-induced growth inhibition48,49,50. Growth suppression may also be linked to heavy metals in pesticide structures, pesticide-induced disturbance of the oxidant-antioxidant balance in cells, loss of cell membrane integrity, and genetically induced cell death51.

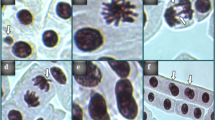

The genotoxic effects of triflumuron insecticide on root meristem cells of A. cepa are shown in Tables 3 and 4, as Fig. 1. As the concentration of triflumuron insecticide increased, MI gradually decreased, while MN and CAs increased (Table 3). The % MI values of TFM 1, TFM 2, and TFM 3 groups decreased by 8.3%, 16.0%, and 25.7%, respectively, compared to the control group. There were significant differences between all values (p < 0.05). The research showed that triflumuron can stop the growth of cells in plants like Vicia faba52. Furthermore, some insecticides in the same group as triflumuron have been called “mitotic poisons” for A. cepa53. For instance, XRD 473 and IKI7899, benzoyl phenyl urea class insecticides like triflumuron, were shown to reduce MI in both Hordeum vulgare and V. faba54. Similarly, MI values decreased with germination and seedling growth of Trigonella foenum - graecum cells treated with a mixture of novaluron and indoxacarb insecticides, which are chitin synthesis inhibitors like triflumuron55.

MI is a parameter used to evaluate the safety of cytotoxic contaminants in the environment and to estimate the frequency of cellular division56. According to Mesi and Kopliku5750% decrease in the mitotic index relative to the control value is regarded as the threshold value. Additionally, the decrease below 50% results in a non-lethal effect on the test organism, while the decrease below 22% signifies a lethal effect. Although the doses of triflumuron utilized in the study did not result in cell death in A. cepa, they elicited a substantial decline in mitotic division. This finding was corroborated by the parallelism between the decrease in cell division (Table 3) and the decline in growth values (Table 2). The arrest of one or more mitotic phases, the obstruction of the G2 phase of the cell cycle, or the inhibition of DNA synthesis can all result in a reduction of MI46. Moreover, the alteration of MI, along with other mitotic cycle abnormalities and CAs, after exposure to pollutants, can be explained by disorganization and depolymerization of microtubules in higher plant cells58. The reduction in MI following triflumuron treatment suggests a possible inhibition of DNA synthesis by this insecticide. The observed inhibition may be attributable to two potential mechanisms: direct interaction of triflumuron with DNA or spindle proteins, or triflumuron-induced ROS accumulation22.

According to Sheikh et al.59insecticides have the potential to be genotoxic to A. cepa. Genomic instability resulting from faulty responses to DNA damage or mitotic chromosomal instabilities can lead to the retention of DNA in abnormal extranuclear structures called MN. MN are, in essence, chromosome fragments resulting from mitotic separation errors or unresolved DNA damage, giving rise to mitotic chromosome bridges and break-fusion-bridge phenomena60. The administration of triflumuron resulted in statistically significant MN accumulation in all groups when compared to the control group (p < 0.05) (Table 3; Fig. 1a). MN frequencies in the TFM 1, TFM 2, and TFM 3 groups were 19.9 ± 4.01, 43.5 ± 3.17, and 63.7 ± 3.77, respectively. Consistent with the results of this study, previous research has shown that triflumuron exposure can increase the number of erythrocytes with MNs in mice, with this increase being dose-dependent61. Furthermore, hexaflumuron, an alternative insect growth inhibitor, has been demonstrated to enhance the incidence of MN in albino rats, depending on the dosage of the insecticide62. De Barros et al.63 also confirmed that diflubenzuron, another insect growth regulator, induced MN formation in mice peripheral blood cells.

Chromosomal alterations, often lethal, arising from chromosomal breakage or alterations in chromosomal material, are designated as CAs64. The study of CAs in A. cepa root tip cells is a valuable route to identify pollutants as “clastogenic”, “genotoxic” or “aneugenic”. Although spontaneous chromosomal aberrations can occur in cells, exposure to chemical or physical pollutants increases the frequency of these abnormalities, depending on the magnitude of the stimulus51. This was confirmed in our study with the very low amount of MN, sticky chromosome, vagrant chromosome and bridge abnormalities observed in the control group (Table 3). On the other hand, triflumuron insecticide application resulted in a series of CAs in root tip cells of A. cepa (Table 3; Fig. 1). The list was formed based on the frequency and included sticky chromosome (Fig. 1b), fragment (Fig. 1c), vagrant chromosome (Fig. 1d), unequal distribution of chromatin (Fig. 1e), and bridge (Fig. 1f). All CAs increased significantly in response to increasing doses of triflumuron. There is no research in the literature showing that triflumuron induces CAs formation in A. cepa. However, fragment formation and chromatid bridging due to this insecticide have been previously reported in V. faba52. Triflumuron has also been shown to be an inducer of CAs, including chromosome breaks, in mice bone marrow cells61. Moreover, insecticides belonging to the benzoyl phenyl urea class, including triflumuron, have been observed to cause certain chromosomal changes in V. faba and H. vulgare, such as stickiness, bridge formation, chromosome fragmentation, and unequal chromosome distribution54.

Stickiness (Fig. 1b), the most common chromosomal defect in the triflumuron-treated groups, is an irreversible abnormality that results from the intense toxic effect of the mutagen on the chromosome and can lead to cell death65. This defect has been reported to be a physiological CA associated with inhibition of the spindle thread system66,67. Irreversible abnormalities in mitosis, such as stickiness, might be due to the decrease in cell division frequency shown in the MI data68. The fragment (Fig. 1c), the second most common CA in insecticide-exposed A. cepa root tip cells, is an indication that the chemical has clastogenic activity56. The irregular distribution of some of the acentric fragments produced by mutagens has been reported to lead to MN formation69,70. The vagrant chromosome, which is associated with spindle defects similar to the sticky chromosome66is the third most intense defect induced by triflumuron (Fig. 1d). As posited by Ogunyemi et al.70a correlation exists between the presence of vagrant chromosomes and the occurrence of uneven distribution of chromosomes and/or double chromatids. Indeed, the unequal distribution of chromatin (Fig. 1e) has been identified as a prevalent CA in A. cepa cells exposed to triflumuron. The bridge (Fig. 1f) is associated with the breakage and subsequent fusion of chromosomes and/or chromatids56. It is categorized as a marker of clastogenicity, leading to defects in DNA structure71. The presence of certain metals in the composition of pesticides may result in the inhibition of DNA repair mechanisms. This inhibition is attributed to the competition with ions necessary for the function of DNA polymerases. This may consequently lead to abnormalities in cell division and the accumulation of CAs in cells56. In addition, the findings of experimental research indicate that pesticides trigger oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and reactive nitrogen species, thereby diminishing the antioxidant capacity of enzymes72. The generation of ROS such as superoxide, hydroxyl, and hydrogen peroxide can cause DNA damage or clastogenicity on chromosomes through oxidation and strand breaks63,73.

The Comet assay is a reliable and relatively affordable technique for detecting DNA damage in single cells. It is sensitive to low levels of damage. Additionally, it is flexible enough to use fresh or frozen samples74. In the Comet assay, chromosomal DNA in cells with damaged DNA exhibits a migratory movement in an electric field, extending out from the nucleus. Following the DNA migration pattern, “a comet-shaped” form is formed, consisting of a head and a tail. This structural organization is established because, during the process of electrophoresis, the broken DNA that constitutes the tail undergoes a greater velocity from the cathode to the anode in comparison to the head. The Comet assay revealed statistically significant differences in the percent of tail DNA in A. cepa root tip cells treated with triflumuron (Table 4). The percentage of tail DNA recorded in the TFM 1 group indicated low damage to DNA, while comet results in the TFM 2 and TFM 3 groups showed that increasing doses of triflumuron caused moderate damage to the DNA of A. cepa root tip cells. Despite the absence of research examining the DNA damage induced by triflumuron in A. cepa, the findings of this study corroborate the Comet results reported by Timoumi et al.75which demonstrated that this insecticide triggered DNA fragmentation in human carcinoma cells. In addition, the insecticide lufenuron, which belongs to the benzoyl phenyl urea class, which also includes triflumuron, has also been shown to cause DNA damage in the internal organs of the non-target organism Oreochromis niloticus by Comet assay76. Ali Abd El-Rahman and Omar77 also demonstrated the DNA damage effect of lufenuron in male rats by Comet assay and associated this effect with oxidative stress.

The presence of breaks in a single strand or both strands of DNA poses a threat to the existence of the plant cell78. In environmental mutagenesis and toxicology studies based on plant roots, the Comet assay enables the detection of not only single and double-strand breaks but also missing break-repair sites and cross-links79. DNA damage manifests predominantly as a consequence of mutations, deletions, cross-linking, and adhesion formation, which ultimately result in the process known as apoptosis80. Timoumi et al.75 reported that triflumuron is a trigger for oxidative stress and that this occurs at the DNA level. Oxidative stress leads to the overproduction of ROS, which can damage cells by oxidizing lipids and degrading DNA and proteins. Accordingly, triflumuron-induced ROS production may be related to genotoxicity, including DNA damage. ROS may modify purine and pyrimidine bases or deoxyribose sugar, as well as induce growth inhibition and single or double-strand breaks in DNA81. It is also noteworthy that a direct reaction between pesticides and nuclear DNA can result in mutagenic and carcinogenic effects75.

The current study showed that triflumuron insecticide caused biochemical toxicity in A. cepa root tip cells (Table 5). The parameters that were investigated to reach this conclusion were the levels of MDA, proline, chlorophyll a, and chlorophyll b, as well as the activities of SOD and CAT enzymes. A statistically significant difference was observed in the biochemical parameter values of all groups treated with triflumuron compared to the control group (p < 0.05). Triflumuron treatment generally caused an increase in MDA and proline levels, enzyme activities, and a decrease in chlorophyll levels. MDA levels in the TFM 1, TFM 2, and TFM 3 groups were approximately 1.8, 2.5, and 3.9 times that of the control group, respectively. An analysis of the proline levels revealed that the TFM 1, TFM 2, and TFM 3 groups exhibited levels of 1.3, 1.8, and 2.1 times the control value, respectively. The increase in SOD and CAT activities was parallel with increased triflumuron dose, as were proline levels and MDA levels. The SOD activities of the TFM 1, TFM 2, and TFM 3 groups were approximately 1.2, 1.4, and 1.8 times the control value, respectively. Similarly, the CAT activities of these groups were approximately 1.5, 2.0, and 2.9 times the control value. The results of the pigment analysis, the sole parameter conducted with the utilization of leaves in the experiment, indicated a decline in chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b levels in all groups following triflumuron application. It was determined that as the triflumuron concentration increased, the severity of the decrease increased concomitantly. Chlorophyll a values in the TFM 1, TFM 2 and TFM 3 groups decreased by 16.4%, 39.5%, and 58.0%, respectively, compared to the control group.

On the other hand, the decrease in chlorophyll b values of TFM 1, TFM 2, and TFM 3 groups was calculated as 12.3%, 31.3%, and 45.3%, respectively, compared to the control. The increase in MDA and the decrease in chlorophyll levels indicate triflumuron-induced damage to the plant. Meanwhile, the increase in proline, SOD, and CAT levels indicated that the plants activated their defense systems against cellular damage. The capacity of triflumuron to modify MDA accumulation and the activity levels of SOD and CAT enzymes has been previously documented by Timoumi et al.75. According to the present study, even at low doses, triflumuron causes cytotoxicity and genotoxicity that may result in cell death, enhances ROS accumulation, induces excessive MDA production, and increases SOD and CAT activity. Similar outcomes were observed in A. cepa in the present study (Tables 3 and 5). In a separate study, five different insect growth regulator insecticides, diflubenzuron, chromaphenozide, chlorfluazuron, lufenuron, and hexaflumuron, caused concentration-dependent oxidative damage and elevated SOD and CAT activities when applied to cotton plants82. Lufenuron was also found to increase MDA levels in albino rats83.

Pesticides have been shown to generate ROS, including superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals84. Enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants are cellular defenses that function to protect cells against oxidative damage from environmental pollutants. SOD, an important member of the enzymatic antioxidant mechanism, is the first enzyme to become more active in response to oxidative stress75. The activity of this enzyme facilitates the conversion of superoxide radicals into hydrogen peroxide and oxygen. In the presence of CAT, hydrogen peroxide is neutralized into water and oxygen84. The elevated activity of both enzymes in all groups treated with triflumuron (Table 5) indicated that even the lowest dose of this insecticide induced superoxide formation, accompanied by SOD activity-mediated or spontaneous hydrogen peroxide production. MDA is the end product of lipid peroxidation, reflecting the extent of ROS-induced oxidative stress in plants and indicating impaired membrane integrity85. Membrane damage decreases ionic permeability and fluidity86leaving the genetic structure vulnerable to pesticide toxicity, as demonstrated in the present study (Tables 3 and 4). Although triflumuron treatment activated the oxidative mechanism in A. cepa root tip cells, even at the lowest dose tested, it caused oxidative stress at a level to targeted cell membranes and genetic integrity. SOD and CAT activities as well as proline, a crucial component of the non-enzymatic defense system, played a role in counteracting this stress (Table 5). This is the first study which provided that triflumuron increased proline levels in plants. However, previous studies have shown that increases in proline levels along with SOD and CAT activities enhance antioxidant defense against pesticide application in plants87. In addition to its role in protein composition, proline plays a variety of functions in plant cells, particularly under abiotic stress conditions. These functions include osmo-protection, the detoxification of ROS, the maintenance of membrane integrity, and the stability of enzymes and proteins88,89. Hatamleh et al.88 posited that an increase in proline levels ensues after exposure to pesticides. Overuse of the insecticide pyriproxyfen, an insect growth regulator similar to triflumuron, has been found to increase proline accumulation in maize plants in a dose-dependent manner38. Similarly, an increase in the expression of stress biomarkers such as proline, MDA, and antioxidant defense enzymes was observed in chickpea plants as the exposure doses of imidacloprid and thiamethoxam insecticides increased42.

Exposure of plants to chemical insecticides causes a reduction of photosynthetic pigments82. The results of this study (Table 5) corroborate other studies in the literature showing insecticide-induced decreases of photosynthetic pigment levels41,42. The decrease in chlorophyll levels may be associated with the disruption of the chloroplast structure and the reduction in the concentration of light-harvesting pigments in the lamellae41. The entry of toxic pollutants, including insecticides, into the plant system, can lead to significant toxicity due to the replacement of Mg2+ at the core of chlorophyll with inorganic ions42. It has also been noted that pesticides can impede the process of plastid formation or the conversion of plastids to chloroplasts90. The inhibition of chlorophyll formation can be attributed to several possible factors, including the accumulation of pesticides within the leaves, interactions with cytosolic enzymes and organic compounds, and dysfunction of the membrane of the chloroplast42. In addition, Edarous91 reported that pesticide exposure may result from the accumulation of phytofluene and phytoene, which inhibit chlorophyll synthesis by blocking dehydrogenation reactions in the biosynthesis of carotenoids.

The structural damages resulting from the exposure of A. cepa meristem cells to triflumuron insecticide are presented in Table 6; Fig. 2. In the control group treated with tap water, the root tip meristem tissue exhibited normal characteristics (Table 6; Fig. 2a, c, f). On the other hand, triflumuron-induced meristematic cell disorders in TFM 1, TFM 2, and TFM 3 groups were epidermis cell damage (Fig. 2b), cortex cell damage (Fig. 2d), thickening of the cortex cell wall (Fig. 2e), and flattened nucleus (Fig. 2g). All damages in the TFM 1 group were categorized as little (Table 6). In the TFM 2 group, cortex cell damage was classified as little damage, while epidermis cell damage, thickening of the cortex cell wall and flattened nucleus were classified as moderate damage. In the TFM 3 group treated with the highest dose of triflumuron, the severity of all damages increased and epidermis cell damage, thickening of the cortex cell wall and flattened nucleus reached a level to be defined as severe damage (Table 6). The results of this study are in agreement with many studies in the literature showing anatomical abnormalities induced by different pesticides in A. cepa root tip meristem tissue92,93,94.

The first areas where plants come into contact with chemicals in their growing environment are the meristematic cells of their roots. Damage to the epidermis cells may be a defense mechanism employed by the plant. In this mechanism, the plant increases the number of epidermal cells or tightens them, thereby preventing the toxic pollutant from penetrating further into the root95. Similarly, the thickening of the cortex cell walls may prevent the chemical that has entered this region from reaching the vascular bundles so that it is not transported to the higher organs of the plant. An irreversible injury known as a flattened nucleus occurs when plants are subjected to hazardous contaminants in excess92. This anomaly may be attributed to the loss of DNA integrity, and physiological and metabolic imbalances96. The CAs present in A. cepa roots (Table 3) and the DNA fragmentation observed by the Comet assay (Table 4) may suggest that the flattening of the cell nucleus is a consequence of genetic damage.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that triflumuron insecticide, a class of insect growth regulators that is widely used globally, exerts its effects by limiting germination and growth, inducing cytotoxic and genotoxic effects, disrupting oxidative balance, and altering the structure of meristematic cells in A. cepa. For the first time, triflumuron-induced toxicity has been comprehensively documented using a model organism known to provide data consistent with the results of studies on mammals. The observation that the toxicity of triflumuron is amplified at elevated exposure doses suggests that the potential impact on non-target organisms should be considered in the dosage determination of such chemicals. The most effective concentration for the target pest and the least toxic concentration for non-target organisms should be considered when selecting the application dose. The developmental strategies are necessary to prevent chemicals with known toxicity risks, including pesticides and residues, from contaminating the habitats of non-target organisms. It is important to take precautions against health problems due to toxicity from these compounds. The development, synthesis, and utilization of safer, target-specific, and environmentally friendly pesticides with fewer side effects should be promoted.

Statement regarding experimental research on plants

Experimental research and field studies on plants and plant parts, including the collection of plant material, comply with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Data availability

This article provides all the data supporting the findings of the study. For further queries, the corresponding author was contacted.

References

Bahar, N. H. et al. Meeting the food security challenge for nine billion people in 2050: what impact on forests. Global Environ. Change. 62, 102056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102056 (2020).

Sarkar, S., Gil, J. D. B., Keeley, J. & Jansen, K. The use of pesticides in developing countries and their impact on health and the right to food. Eur. Union. https://doi.org/10.2861/28995 (2021).

Tudi, M. et al. Agriculture development, pesticide application and its impact on the environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031112 (2021).

Zaller, J. G. et al. Pesticides in ambient air, influenced by surrounding land use and weather, pose a potential threat to biodiversity and humans. Sci. Total Environ. 838, 156012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156012 (2022).

Mohankumar, L., Thiyaharajan, M. & Venkidusamy, K. S. Understanding the communication network of farmers to ensure the sustainable use of pesticides. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 14, 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-023-00861-6 (2024).

Sood, P. Pesticides usage and its toxic effects-a review. Indian J. Entomol. 86, 339–347. https://doi.org/10.55446/IJE.2023.505 (2024).

Mostafalou, S. & Abdollahi, M. Pesticides and human chronic diseases: evidences, mechanisms, and perspectives. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 268, 157–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2013.01.025 (2013).

Timoumi, R., Amara, I., Salem, I. B., Souid, G. & Abid-Essefi Mini‐review highlighting toxic effects of triflumuron in insects and mammalian systems. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 37, e23341. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbt.23341 (2023).

Belinato, T. A., Martins, A. J., Lima, J. B. P. & Valle, D. Effect of triflumuron, a Chitin synthesis inhibitor, on Aedes aegypti, Aedes albopictus and Culex quinquefasciatus under laboratory conditions. Parasite Vectors. 6, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-6-83 (2013).

Timoumi, R. et al. Acute triflumuron exposure induces oxidative stress responses in liver and kidney of balb/c mice. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 26, 3723–3730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-3908-8 (2019).

Masetti, A., Depalo, L. & Pasqualini, E. Impact of triflumuron on Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae): laboratory and field studies. J. Econ. Entomol. 114, 1709–1715. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toab102 (2021).

Merzendorfer, H. & Zimoch, L. Chitin metabolism in insects: structure, function and regulation of Chitin synthases and Chitinases. J. Exp. Biol. 206, 4393–4412. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.00709 (2003).

Vazirianzadeh, B., Jervis, M. A. & Kidd, N. A. The effects of oral application of cyromazine and triflumuron on house-fly larvae. J. Arthropod-Borne Dis. 1, 7–13 (2007).

Junquera, P., Hosking, B., Gameiro, M. & Macdonald, A. Benzoylphenyl Ureas as veterinary antiparasitics. An overview and outlook with emphasis on efficacy, usage and resistance. Parasite 26, 26. https://doi.org/10.1051/parasite/2019026 (2019).

Yang, L. et al. A new strategy for efficient detection of triflumuron residues in food: an electrochemical sensor derived from a Cu/Fe-BTC MOF-polymer. Ind. Crops Prod. 218, 118954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.118954 (2024).

Xiao, C. & Xie, Y. The expanding energy prospects of metal organic frameworks. Joule 1, 25–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2017.08.014 (2017).

de Souza, C. P., Guedes, T. D. A. & Fontanetti, C. S. Evaluation of herbicides action on plant bioindicators by genetic biomarkers: a review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 188, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-016-5702-8 (2016).

Khanna, N. & Sharma, S. Allium cepa root chromosomal aberration assay: a review. Indian J. Pharm. Biol. Res. 1, 105–119 (2013).

Bonciu, E. et al. An evaluation for the standardization of the Allium cepa test as cytotoxicity and genotoxicity assay. Caryologia 71, 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/00087114.2018.1503496 (2018).

Camilo-Cotrim, C. F., Bailão, E. F. L. C., Ondei, L. S. & Carneiro, F. M. Almeida L.M. What can the Allium cepa test say about pesticide safety? A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 29, 48088–48104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-20695-z (2022).

Badawy, M. E., Kenawy, A. & El-Aswad, A. F. Toxicity assessment of buprofezin, lufenuron, and triflumuron to the earthworm Aporrectodea caliginosa. Int. J. Zool. 1–9. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/174523 (2013).

Timoumi, R., Amara, I., Ben Salem, I. & Abid-Essefi, S. Triflumuron induces cytotoxic effects on hepatic and renal human cell lines. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 34, e22504. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbt.22504 (2020).

Pehlivan, Ö. C., Çavuşoğlu, K., Yalçın, E. & Acar, A. In Silico ınteractions and deep neural network modeling for toxicity profile of Methyl methanesulfonate. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 30, 117952–117969. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-30465-0 (2023).

Atik, M., Karagüzel, O. & Ersoy, S. Effect of temperature on germination characteristics of Dalbergia sissoo seeds. Mediterr. Agric. Sci. 20, 203–210 (2007).

Staykova, T. A., Ivanova, E. N. & Velcheva, D. G. Cytogenetic effect of heavy-metal and cyanide in contaminated waters from the region of Southwest Bulgaria. J. Cell. Mol. Biol. 4, 41–46 (2005).

Himtaş, D., Yalçın, E., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Acar, A. In-vivo and in-silico studies to identify toxicity mechanisms of permethrin with the toxicity-reducing role of ginger. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 31, 9272–9287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-31729-5 (2024).

Fenech, M. et al. HUMN project: detailed description of the scoring criteria for the cytokinesis-block micronucleus assay using isolated human lymphocyte cultures. Mutat. Res. 534, 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1383-5718(02)00249-8 (2003).

Sharma, N., Biswas, S., Al-Dayan, N., Alhegaili, A. S. & Sarwat, M. Antioxidant role of Kaempferol in prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma. Antioxidants 10, 1419. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10091419 (2021).

Dikilitaş, M. & Koçyiğit, A. Analysis of DNA damage in organizms via single cell gel electrophoresis (technical note): comet assay method. J. Agric. Fac. HR U. 14, 77–89 (2010).

Pereira, C. S. A. et al. Evaluation of DNA damage induced by environmental exposure to mercury in Liza aurata using the comet assay. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 58, 112–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00244-009-9330-y (2010).

Zou, J., Yue, J., Jiang, W. & Liu, D. Effects of cadmium stress on root tip cells and some physiological indexes in Allium cepa var. Agrogarum L. Acta Biol. Cracov. Bot. 54, 129–141. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10182-012-0015-x (2012).

Beauchamp, C. & Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 44, 276–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(71)90370-8 (1971).

Beers, R. F. & Sizer, I. W. Colorimetric method for Estimation of catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 195, 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(19)50881-X (1952).

Unyayar, S., Celik, A., Çekiç, F. Ö. & Gözel, A. Cadmium-induced genotoxicity, cytotoxicity and lipid peroxidation in Allium sativum and Vicia faba. Mutagenesis 21, 77–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/mutage/gel001 (2006).

Kaydan, D., Yagmur, M. & Okut, N. Effects of Salicylic acid on the growth and some physiological characters in salt stressed wheat (Triticum aestivum L). J. Agr Sci. 13, 114–119. https://doi.org/10.1501/Tarimbil_0000000444 (2007).

Witham, F. H., Blaydes, D. R. & Devlin, R. M. in Experiments in Plant Physiology. (eds Witham, F. H.) (Van Nostrand Reinhold Co, 1971).

Altunkaynak, F., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Yalçın, E. Detection of heavy metal contamination in Batlama stream (Türkiye) and the potential toxicity profile. Sci. Rep. 13, 11727. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39050-4 (2023).

Saladin, G. & Clément, C. Nova Science Publishers,. Physiological side effects of pesticides on non-target plants in Agriculture and soil pollution: new research (ed. Livingston, J. V.) 53–86 (2005).

Kamal, A., Ahmad, F. & Shafeeque, M. A. Toxicity of pesticides to plants and non-target organism: a comprehensive review. Iran. J. Plant. Physiol. 10, 3299–3313. https://doi.org/10.30495/ijpp.2020.1885628.1183 (2020).

Kumar, S. & Sharma, J. G. Effect of malathion on seed germination and photosynthetic pigments in wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Asian J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 1, 158–167 (2017).

Coskun, Y., Kilic, S. & Duran, R. E. The effects of the insecticide Pyriproxyfen on germination, development and growth responses of maize seedlings. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 24, 278–284 (2015).

Shahid, M., Khan, M. S., Ahmed, B., Syed, A. & Bahkali, A. H. Physiological disruption, structural deformation and low grain yield induced by neonicotinoid insecticides in chickpea: a long term phytotoxicity investigation. Chemosphere 262, 128388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128388 (2021).

Dhungana, S. K., Kim, I. D., Kwak, H. S. & Shin, D. H. Unraveling the effect of structurally different classes of insecticide on germination and early plant growth of soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr]. Pestic Biochem. Phys. 130, 39–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2015.12.002 (2016).

Veeraswamy, J., Padmavathi, T. & Venkateswarlu, K. Effect of selected insecticides on plant growth and mycorrhizal development in sorghum. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 43, 337–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-8809(93)90096-8 (1993).

Smith, G. A. & Moser, H. S. Sporophytic-gametophytic herbicide tolerance in sugarbeet. Theor. Appl. Genet. 71, 231–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00252060 (1985).

Onuminya, T. O. & Eze, T. E. Cytogenotoxic effects of Cypermethrin on root growth: Allium sativum as a model system. As Pac. J. Mol. Biol. Biotechnol. 27, 54–61. https://doi.org/10.35118/apjmbb.2019.027.4.06 (2019).

Silveira, G. L., Lima, M. G. F., Reis, D., Palmieri, G. B., Andrade-Vieria, L. F. & M. J. & Toxic effects of environmental pollutants: comparative investigation using Allium cepa L. and Lactuca sativa L. Chemosphere 178, 359–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.03.048 (2017).

Aktar, W., Sengupta, D. & Chowdhury, A. Impact of pesticides use in agriculture: their benefits and hazards. Interdiscip Toxicol. 2, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10102-009-0001-7 (2009).

Begum, N. et al. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in plant growth regulation: implications in abiotic stress tolerance. Front. Plant. Sci. 10, 1068. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.01068 (2019).

Macar, O., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Çavuşoğlu, K., Yalçın, E. & Acar, A. Assessing the combined toxic effects of metaldehyde mollucide. Sci. Rep. 13, 4888. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32183-6 (2023).

Macar, O., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Çavuşoğlu, K., Yalçın, E. & Yapar, K. Lycopene: an antioxidant product reducing dithane toxicity in Allium cepa L. Sci. Rep. 13, 2290. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29481-4 (2023).

Rukmanski, G. & Dimova, P. Study of the effect of the insecticides dimilin and Alsystin on chromosome structure in Vicia faba. Ekologicheskaya Kooperatsiya. 1-2, 142–146 (1990).

Eissa, R. A. & Eisa, A. A. Cytological effects of the insect growth regulator (IGR) Fenoxycarb on mitotic cells of onion Allium cepa. Ann. Agric. Sci. Moshtohor. 28, 2555–2565 (1990).

Abdel-Rahem, A. T. & Ragab, R. A. K. Somatic chromosomal aberrations induced by benzoylphenylurea (XRD 473 and IKI 7899) in Vicia faba L. and Hordeum vulgare L. Cytologia 54, 627–634. https://doi.org/10.1508/cytologia.54.627 (1989).

Mahapatra, K., De, S., Banerjee, S. & Roy, S. Pesticide mediated oxidative stress induces genotoxicity and disrupts chromatin structure in Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) seedlings. J. Hazard. Mater. 369, 362–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.02.056 (2019).

Rodríguez, Y. A. et al. Allium cepa and Tradescantia pallida bioassays to evaluate effects of the insecticide Imidacloprid. Chemosphere 120, 438–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.08.022 (2015).

Mesi, A. & Kopliku, D. Cytotoxic and genotoxic potency screening of two pesticides on Allium cepa L. Proc. Technol. 8, 19–26 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protcy.2013.11.005

Yekeen, T. A. & Adeboye, M. K. Cytogenotoxic effects of cypermethrin, deltamethrin, lambdacyhalothrin and endosulfan pesticides on Allium cepa root cells. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 12 https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB2013.12802 (2013).

Sheikh, N., Patowary, H. & Laskar, R. A. Screening of cytotoxic and genotoxic potency of two pesticides (malathion and cypermethrin) on Allium cepa L. Mol. Cell. Toxicol. 16, 291–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13273-020-00077-7 (2020).

Adams, D. J. et al. Genetic determinants of micronucleus formation in vivo. Nature 627, 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-07009-0 (2024).

Timoumi, R., Amara, I., Ayed, Y., Ben Salem, I. & Abid-Essefi, S. Triflumuron induces genotoxicity in both mice bone marrow cells and human colon cancer cell line. Toxicol. Mech. Methods. 30, 438–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/15376516.2020.1758981 (2020).

Noaishi, M. A., Alhafez, A., Abdulrahman, S. A. & H. H. & Evaluation of the repeated exposure of hexaflumuron on liver and spleen tissues and its mutagenicity ability in male albino rat. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 76, 4545–4552. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejhm.2019.45039 (2019).

De Barros, A. L. et al. Genotoxic and mutagenic effects of diflubenzuron, an insect growth regulator, on mice. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part. A. 76, 1003–1006. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287394.2013.830585 (2013).

Aslantürk, Ö. S. Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of Triphenyl phosphate on root tip cells of Allium cepa L. Vitro Toxicol. 94, 105734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tiv.2023.105734 (2024).

Kumar, P. & Prasad, V. Cytotoxic and mitodepressive effect of insecticide Profenofos on root meristem of Allium cepa L. Environ. Ecol. 42, 420–426. https://doi.org/10.60151/envec/JQAI6367 (2024).

Schreiner, G. E. et al. Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of aqueous extracts of Aloysia gratissima (Gillies & Hook.) tronc. Using Allium cepa L. assay. Pharmacol. Res. Nat. Prod. 2, 100011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prenap.2023.100011 (2024).

Hussein, N. J. & Saadullah, A. A. Cytogenotoxic effect of trichothecene T2 toxin on Allium sativum root tip meristematic cells. Bionatura 1, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.21931/RB/2024.09.01.45 (2024).

Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Macar, O., Çavuşoğlu, K., Yalçin, E. & Yapar, K. Turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) tends to reduce the toxic effects of nickel (II) chloride in Allium cepa L. roots. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 29, 60508–60518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-20171-8 (2022).

Salim, T. M. S., Bekhit, M. M. M. & Soudy, F. A. Cytotoxic effects of chemical mutagens in root tip cells of Allium cepa L. J. Agr Chem. Biotechnol. 14, 99–108. https://doi.org/10.21608/jacb.2023.219711.1057 (2023).

Ogunyemi, A. K. et al. Alkaline extracted cyanide from cassava wastewater and its sole induction of chromosomal aberrations on Allium cepa L. root tips. Environ. Technol. 15, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593330.2021.1916088 (2021).

Wijeyaratne, W. M. & Wickramasinghe, P. G. Chromosomal abnormalities in Allium cepa induced by treated textile effluents: Spatial and Temporal variations. J. Toxicol. 3, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8814196 (2020).

Sule, R. O., Condon, L. & Gomes, A. V. A common feature of pesticides: oxidative stress-the role of oxidative stress in pesticide-induced toxicity. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 5563759. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5563759 (2022).

Prathiksha, J., Narasimhamurthy, R. K., Dsouza, H. S. & Mumbrekar, K. D. Organophosphate pesticide-induced toxicity through DNA damage and DNA repair mechanisms. Mol. Biol. Rep. 50, 5465–5479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-023-08424-2 (2023).

Prajapati, P., Gupta, P., Kharwar, R. N. & Seth, C. S. Nitric oxide mediated regulation of ascorbate-glutathione pathway alleviates mitotic aberrations and DNA damage in Allium cepa L. under salinity stress. Int. J. Phytorem. 25, 403–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/15226514.2022.2086215 (2023).

Timoumi, R., Salem, I. B., Amara, I., Annabi, E. & Abid-Essefi, S. Protective effects of fennel essential oil against oxidative stress and genotoxicity induced by the insecticide triflumuron in human colon carcinoma cells. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 27, 7957–7966. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-07395-x (2020).

Al-Saeed, F. A. et al. Oxidative stress, antioxidant enzymes, genotoxicity and histopathological profile in Oreochromis niloticus exposed to Lufenuron. Pakistan Vet. J. 43, 160–166. https://doi.org/10.29261/pakvetj/2023.012 (2023).

El-Rahman, A. A., Omar, A. R. & H. & Ameliorative effect of avocado oil against Lufenuron induced testicular damage and infertility in male rats. Andrologia 54, e14580. https://doi.org/10.1111/and.14580 (2022).

Tyutereva, E. V., Strizhenok, A. D., Kiseleva, E. I. & Voitsekhovskaja, O. V. Comet assay: multifaceted options for studies of plant stress response. Horticulturae. 10, 174. (2024). https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae10020174

Liman, R., Ciğerci, İ. H., Akyıl, D., Eren, Y. & Konuk, M. Determination of genotoxicity of Fenaminosulf by Allium and comet tests. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 99, 61–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2010.10.006 (2011).

Kizilkaya, D. et al. Comparative investigation of iron oxide nanoparticles and microparticles using the in vitro bacterial reverse mutation and in vivo Allium chromosome aberration and comet assays. J. Nanoparticle Res. 25, 173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-023-05819-x (2023).

Liman, R., Ciğerci, İ. H. & Öztürk, N. S. Determination of genotoxic effects of Imazethapyr herbicide in Allium cepa root cells by mitotic activity, chromosome aberration, and comet assay. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 118, 38–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2014.11.007 (2015).

El-Zahi, E. Z. S., Keratum, A. Y., Hosny, A. H. & Yousef, N. Y. E. Efficacy and field persistence of Pyridalyl and insect growth regulators against Spodoptera littoralis (Boisduval) and the induced oxidative stress in cotton. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 42, 2795–2802. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42690-020-00419-x (2021).

Basal, W. T., Ahmed, A. R. T., Mahmoud, A. A. & Omar, A. R. Lufenuron induces reproductive toxicity and genotoxic effects in pregnant albino rats and their fetuses. Sci. Rep. 10, 19544. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76638-6 (2020).

Pesala, R. S. & Yerragudi, S. Pesticide induced oxidative stress on non-target organism Labeo rohita. Int. J. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 50, 585–590. https://doi.org/10.55863/ijees.2024.0116 (2024).

Wu, Y. et al. Exogenous epigallocatechin-3-gallate alleviates pesticide phytotoxicity and reduces pesticide residues by stimulating antioxidant defense and detoxification pathways in melon. J. Plant. Growth Regul. 43, 434–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-023-11092-y (2024).

Forti, J. C. et al. Electrochemical processes used to degrade Thiamethoxam in water and toxicity analyses in non-target organisms. Processes 12, 887. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12050887 (2024).

Bhat, A. A. et al. Exploiting fly Ash as an ecofriendly pesticide/nematicide on Abesmoschus esculuntus: insights into soil amendment-induced antioxidant fight against nematode mediated ROS. Chemosphere 358, 142143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.142143 (2024).

Hatamleh, A. A., Danish, M., Al-Dosary, M. A., El-Zaidy, M. & Ali, S. Physiological and oxidative stress responses of Solanum lycopersicum (L.) (tomato) when exposed to different chemical pesticides. RSC Adv. 12, 7237–7252. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1RA09440H (2022).

Spormann, S. et al. Accumulation of proline in plants under contaminated soils-are we on the same page? Antioxidants 12, 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox12030666 (2023).

Salem, R. E. E. S. Side effects of certain pesticides on chlorophyll and carotenoids contents in leaves of maize and tomato plants. Middle East. J. 5, 566–571 (2016).

Edarous, R. Side effects of certain pesticides on the relationship between plant and soil, Zigzag University, Faculty of Agriculture, Doctoral dissertation, Ph. D. thesis, Egypt (2011).

Macar, O., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Yalçın, E. Protective effects of anthocyanin-rich Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) extract against copper (II) chloride toxicity. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 27, 1428–1435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-06781-9 (2020).

Kalefetoğlu Macar, T. Investigation of cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of abamectin pesticide in Allium cepa L. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 28, 2391–2399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-10708-0 (2021).

Yirmibeş, F., Yalçin, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Protective role of green tea against Paraquat toxicity in Allium cepa L.: physiological, cytogenetic, biochemical, and anatomical assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 29, 23794–23805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17313-9 (2022).

Yalçin, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Spectroscopic contribution to glyphosate toxicity profile and the remedial effects of Momordica charantia. Sci. Rep. 12, 20020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24692-7 (2022).

Çavuşoğlu, D., Yalçin, E., Çavuşoğlu, K., Acar, A. & Yapar, K. Molecular Docking and toxicity assessment of spirodiclofen: protective role of lycopene. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 28, 57372–57385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-14748-y (2021).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.B, T.K.M., K.Ç. and E.Y. designed the experiments and performed the analyses; K.Ç. carried out the statistical analysis; G.B., T.K.M. and E.Y. wrote the manuscript with the help of K.Ç.; T.K.M. edited the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bıyıksız, G., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Çavuşoğlu, K. et al. A study investigating the multifaceted toxicity induced by triflumuron insecticide in Allium cepa L. Sci Rep 15, 24839 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10777-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10777-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Eco-friendly remediation of Triflumuron-induced stress with Capsella bursa-pastoris extract

Scientific Reports (2025)