Abstract

Nomophobia has become an increasingly common mental health concern among college students. While prior research has examined various factors contributing to nomophobia, the relationships among social avoidance, loneliness, and self-control within the Chinese context remain underexplored. This study aims to investigate the impact of social avoidance on nomophobia, with a particular focus on the parallel mediating roles of loneliness and self-control. Data were obtained through a survey of 1,008 college students (48% male, n = 484, M = 19.62, SD = 1.88; 52% female, n = 524, M = 20.57, SD = 2.41), and path analysis was used to test the hypotheses. The results revealed that social avoidance significantly predicts nomophobia and that this effect is mediated by both loneliness and self-control. These findings underscore the importance of addressing social avoidance, loneliness, and self-control in efforts to prevent nomophobia. Promoting social engagement may enhance psychological well-being and reduce the risk of nomophobia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the swift progress of internet technology, smartphones have become an integral part of people’s everyday lives, causing a growing reliance on these devices. When separated from their phones, individuals often experience anxiety and fear, a phenomenon referred to as “No Mobile Phone Phobia (Nomophobia)”1. In China, smartphone usage continues to grow, with adolescents accounting for approximately 30% of the total users as of 20232. Among these, college students aged 18 to 25 are particularly prone to moderate to severe nomophobia3. Nomophobia has significant negative effects on both the mental and physical well-being of college students, such as increased stress4, depression5, decreased academic performance and sleep quality6,7. Therefore, investigating the influencing factors and underlying mechanisms of nomophobia among college students is of critical practical importance.

Social avoidance is a specific behavioral manifestation of social anxiety and has been identified as a key predictor of nomophobia8,9. In China, a nationwide survey covering 255 universities and collecting 4,854 valid responses revealed that 80.22% of college students considered themselves to have mild social anxiety10 Concurrently, a cross-temporal meta-analysis indicated that between 2000 and 2020, Chinese college students’ social anxiety scores increased by 0.92 standard deviations11. This trend may be associated with developmental characteristics of emerging adulthood, a period marked by heightened identity exploration and interpersonal sensitivity. During this stage, individuals are more likely to experience anxiety in response to the uncertainty of social outcomes such as evaluation, rejection, or embarrassment12. At the university level, students face challenges such as social integration, role adaptation, and identity reconstruction. When lacking adequate coping resources, they are more prone to anxiety and may adopt avoidant strategies to shield themselves from potential negative experiences13. In the sociocultural context of China, young people often grow up in an environment characterized by high expectations and intense social comparison, which fosters greater self-doubt regarding their social competence. Moreover, the utilitarian and performance-oriented nature of higher education in China tends to reduce students’ opportunities for social engagement and undermines their social confidence11. According to the self-regulation model, individuals under stress or anxiety may engage in behaviors that help relieve discomfort14,15. For example, a latent profile analysis revealed that individuals with high levels of social anxiety tend to use mobile phones more frequently, as phones provide a sense of security and reduce the discomfort associated with face-to-face interactions9. Over time, such emotionally compensatory phone use may become habitual and develop into a psychological dependence—namely, nomophobia.

Furthermore, social avoidance may increase the risk of nomophobia through its effects on loneliness and self-control. Previous studies have shown that individuals who avoid social interactions tend to experience higher levels of loneliness, which is a significant psychological risk factor among university students16,17. In addition, socially avoidant individuals are inclined to withdraw from interpersonal evaluation and interaction. This persistent avoidance may elevate psychological stress and impair self-regulatory capacity, thereby reducing one’s self-control8,18 In such situation, individuals may repeatedly check their phones to alleviate internal anxiety, and the absence of their phones could induce fear or distress19,20 Loneliness and self-control likely represent distinct emotional and cognitive responses to social withdrawal. Given the lack of strong theoretical or empirical evidence establishing a specific causal sequence between them, the present study adopts a parallel mediation model. A more detailed explanation of this theoretical rationale is provided in the following section. Accordingly, this study aims to investigate the underlying mechanisms linking social avoidance and nomophobia, with a particular focus on the parallel mediating roles of loneliness and self-control.

Theoretical framework

Nomophobia, first introduced in a 2008 study by the UK Post Office, describes the anxiety and fear that individuals feel when they cannot access or use their mobile devices, or when they lose connection to them3. While nomophobia is closely related to smartphone addiction, the two phenomena are distinct. Smartphone addiction refers to behavioral dependence on various activities conducted via mobile devices, characterized by craving, loss of control, tolerance, and withdrawal symptoms21, which can result in difficulties affecting physical health, mental well-being, and social interactions. Conversely, nomophobia specifically focuses on the emotional reaction’s individuals experience when they are unable to use or access their mobile phones, manifesting in feelings of disconnection, inability to communicate, loss of information access, and inconvenience22.

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) offers a foundational perspective for analyzing the concept of nomophobia. SDT posits that healthy psychological development and optimal functioning are supported by the satisfaction of three basic psychological needs: autonomy (the feeling that one’s behavior is self-endorsed), competence (the feeling of being capable of meeting challenges), and relatedness (the feeling of being connected and accepted by others)23,24. Social avoidance behavior restricts interpersonal connections and reduces opportunities for individuals to establish meaningful relationships, thereby undermining the satisfaction of the need for relatedness and potentially leading to increased loneliness. Loneliness, as a negative emotional state, prompts individuals to seek external solutions—such as reliance on smartphones—to alleviate emotional distress and meet their basic psychological needs8,16,22. Meanwhile, from the SDT perspective, social avoidance may cause individuals to feel incompetent in social interactions and unable to control the feedback they receive from others, leading to a sense of learned helplessness. According to the self-control resource theory25, such helplessness depletes cognitive and emotional resources, impairing individuals’ ability to regulate impulses and behaviors—key aspects of self-control. In this state, individuals may turn to frequent smartphone use to divert attention or escape discomfort. Therefore, increased loneliness and reduced self-control may represent two parallel consequences of social avoidance, without a clearly defined temporal or causal sequence. For example, previous research has shown that loneliness does not significantly mediate the effect of self-control on nomophobia26. When the causal order of mediators cannot be clearly established through theory or empirical findings, employing a parallel mediation model helps avoid bias introduced by arbitrary path assumptions and allows for more accurate estimation of each indirect effect27. Taken together, the inclusion of loneliness and self-control as parallel mediators between social avoidance and nomophobia is supported by both theoretical reasoning and empirical evidence, offering a clearer understanding of how social avoidance may influence psychological states and behavioral outcomes.

Social avoidance and nomophobia

With the rise of social platforms such as Tiktok, WeChat, and QQ, the way college students engage in social interactions has shifted significantly28. Face-to-face communication has declined, while online interactions have increased29. Although virtual socializing facilitates the accumulation of online social capital among adolescents30, it has also contributed to heightened social anxiety and avoidance behaviors, particularly during phases of peer pressure, academic competition, and identity formation31. The anonymity and convenience of virtual social interactions allow socially avoidant individuals to evade real-world social pressures and achieve temporary psychological relief32. Consequently, they become increasingly reliant on smartphones as a tool for distraction29. This growing dependence on smartphones for social engagement leaves individuals more vulnerable to anxiety and fear when access to their phones is restricted, thereby intensifying nomophobia symptoms.

Social avoidance, by reducing opportunities for in-person social interactions, drives individuals to turn to their smartphones to meet social needs, inadvertently increasing their dependence on these devices. This reliance becomes problematic when they are separated from their phones, triggering elevated levels of anxiety and fear, hallmark symptoms of nomophobia. Therefore, social avoidance may not only serve as a significant risk factor for nomophobia but may also act as a key mechanism through which fear of being without a mobile phone develops and persists. Investigating this relationship is essential to enhancing our knowledge of nomophobia’s development and finding effective methods to prevent and alleviate this growing concern among college students.

Mediating role of loneliness

Social avoidance is often associated with a range of negative emotions, particularly loneliness33. Social avoidance reduces opportunities for individuals to gain social support and build interpersonal relationships, leading to a lack of emotional feedback and, consequently, increased feelings of loneliness34. In the context of China’s collectivist culture, social avoidance may violate social norms that emphasize maintaining group harmony and cohesion, further intensifying feelings of loneliness8,35. As loneliness intensifies, individuals may seek emotional support through instant messaging or social media, and this dependence on immediate feedback further exacerbates nomophobia36. Numerous empirical studies have identified loneliness as a significant predictor of nomophobia. For example, Gezgin and Yildirim37 found that loneliness significantly predicted nomophobia among 929 Turkish high school students. Similarly, in a cross-cultural study, Ozdemir, Cakir, and Hussain38 pointed out that loneliness, self-esteem, and subjective well-being all significantly predicted the occurrence of nomophobia, with loneliness playing a particularly prominent role.

Mediating role of self-control

Self-control is defined as a person’s capacity to adjust to their environments by inhibiting impulses and adjusting behavior, serving as a fundamental mechanism for self-regulation39. Individuals with high self-control exhibit strong planning abilities, greater impulse control, and effective coping strategies for negative emotions20. In contrast, individuals with low self-control tend to act impulsively and struggle to cope with changes in their environment40. Although there is currently limited research directly confirming the mediating role of self-control in the relationship between social avoidance and nomophobia, several empirical studies offer indirect support41,42,43. According to the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) introduced earlier, social avoidance restricts opportunities for interpersonal interaction, thereby undermining individuals’ needs for relatedness and competence. A study conducted in Italy among university students found that when these basic psychological needs—particularly relatedness and competence—were unmet, individuals’ self-control decreased, which in turn led to higher levels of nomophobia41. In that study, self-control fully mediated the relationship between psychological needs and nomophobia. Furthermore, both objective social isolation and subjective social avoidance reduce the frequency of social interactions. Existing research has shown that during the COVID-19 pandemic, reduced opportunities for social interaction led to a decline in college students’ self-control and subsequently increased their risk of internet addiction42. Although Guo et al. (2024) did not specifically address nomophobia, excessive use of the internet or smartphones can be classified as problematic behaviors. Thus, their findings provide indirect support for the notion that social avoidance may increase nomophobia through its negative impact on self-control.

Purpose of the study

In recent years, research on mobile phone dependence has increased. However, few studies have explored social avoidance as an independent factor and its impact on nomophobia through loneliness and self-control. This approach is rare in the existing literature. Most studies have focused either on loneliness or self-control alone. In contrast, this study examines both factors together. This helps improve our understanding of the mechanisms behind nomophobia and expands the existing psychological framework. Additionally, in China’s collectivist culture, individuals often rely on social approval and support. Social avoidance may be viewed as behavior that goes against social expectations, which can lead to greater loneliness. As a result, people may turn to their phones to escape the pressures of social interaction. This dependency can, in turn, worsen nomophobia. This provides a perspective distinct from Western cultural contexts. Based on this framework, the study proposes two hypotheses:

-

(1)

Social avoidance significantly predicts nomophobia.

-

(2)

Loneliness and self-control serve as simultaneous mediators linking social avoidance to nomophobia.

Methods

Data and participants

This study employed a random sampling method and recruited 1,135 undergraduate and graduate students from two universities located in Xiangyang, Hubei Province, and Zhanjiang, Guangdong Province, between March and May 2024. Participants willingly took part in an online survey using the “Wenjuanxing” platform, an online survey tool created in China. To ensure data accuracy, 127 respondents who had received psychological counseling services in the past month were removed from the dataset, resulting in a final sample size of 1,008 individuals (48% male, n = 484, M = 19.62, SD = 1.88; 52% female, n = 524, M = 20.57, SD = 2.41). Each participant provided informed consent before filling out the questionnaire, and their involvement in the study was completely voluntary. This study was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hubei University of Arts and Science (Approval No.: 2024-020). Prior to data collection, all participants provided written informed consent.

Measurements

Nomophobia

Nomophobia describes the feelings of anxiety and fear that people encounter when they are unable to access their mobile phones or when their devices are out of reach44. Yildirim et al.1 developed the Questionnaire for Measuring Nomophobia (NMP-Q), which has been adapted in various countries and extensively used in related research45. However, three items from the original English version of the scale (items 9, 10, and 15) were found to be ineffective in distinguishing participants within the Chinese context, and item 20 presented translation ambiguities — particularly, the phrase “I would feel weird because I would not know what to do.” As a result, Ren and colleagues44 removed these four items in their study, reducing the revised Chinese version of the NMP-Q from 20 items to 16. Although the internal consistency coefficient slightly decreased from 0.976 to 0.931, the reliability of each dimension remained at a high level. Furthermore, the revised Chinese version has been validated in several empirical studies, demonstrating its applicability to Chinese college students46,47.

The Chinese version of the NMP-Q retains the four dimensions from the original scale: fear of failing to access information, fear of losing convenience, fear of losing communication, and fear of losing network connection. Each dimension includes four items, evaluated using a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 indicates strong disagreement and 7 indicates strong agreement. The aggregate score represents the general level of nomophobia, with higher values signifying greater severity. This study uses the four dimensions of nomophobia as latent variables to capture the core features of nomophobia comprehensively. Employing latent variables enables a more precise understanding of the commonalities between dimensions, helping to avoid multicollinearity issues and enhancing the model’s applicability and explanatory power. To assess the structural validity of the Chinese version of the NMP-Q and examine whether it retained the original four-factor structure, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted. The data fit the model well: χ2/df = 6.171, TLI = 0.955, CFI = 0.963, RMSEA = 0.072. All items had factor loadings above 0.70 (The factor loadings of the model are presented in Appendix Figure S.1), indicating good structural validity of the scale. In addition, the internal consistency reliability of the scale was evaluated. The overall Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.96, with alpha values of 0.85, 0.88, 0.92, and 0.94 for the four dimensions, respectively.

Social avoidance

The Social Avoidance and Distress Scale, created by Watson and Friend in 196948, includes two subscales to measure an individual’s tendency to avoid others in social situations and the distress experienced in such settings. This study utilized only the social avoidance subscale containing 14 questions: seven positively worded items: seven positively worded items and seven reverse-scored items. Each item is scored as a binary variable (0 = no, 1 = yes), with reverse items coded accordingly. The overall score spans from 0 to 14, where higher scores reflect a greater inclination towards avoiding social interactions.

Loneliness

The University of California Los Angeles Loneliness Scale (ULS-20) scale is a widely used tool for assessing individuals’ loneliness. However, to provide a simpler and more efficient tool for assessing loneliness in social interactions, Hays et al.49 revised the ULS-2050 and developed the ULS-8 scale. This scale measures subjective loneliness and has been validated as a unidimensional scale with good reliability and validity, making it a suitable alternative to the ULS-20. The ULS-8 includes eight items: six positively worded items (e.g., “I feel like I lack companionship”) and two reverse-scored items (e.g., “I am a person who is willing to make friends”). This scale employs a 4-point Likert format (1 = never, 4 = always). In this study, the two reverse-scored items were coded accordingly, with the total score ranging from 8 to 32, higher scores reflect increased levels of loneliness. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.77, indicating acceptable internal consistency.

Self-control

Self-control, defined as the ability to manage internal emotional responses51, is assessed using the Self-Control Scale (SCS). This study utilized the 13-item Brief SCS, which includes four positively worded items and nine reverse-scored items for ease of response. Items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with reverse-scored items adjusted appropriately. The total score spans from 13 to 65, with higher values reflecting greater levels of self-control. In this study, the scale achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78, showing satisfactory internal consistency.

Covariates

Based on existing research, this study included multiple covariates to better estimate the factors influencing nomophobia. These covariates encompass (i) sociodemographic characteristics: age, gender, academic year, major, and family background; (ii) socioeconomic status: average monthly income; and (iii) basic lifestyle factors: daily smartphone usage, academic stress, and weekly exercise frequency. Prior studies have shown significant associations between these variables and nomophobia. For instance, males and females display significant differences in nomophobic symptoms38,52, with young adults aged 18 to 24 most susceptible to nomophobia3. Moreover, daily smartphone use is closely linked to nomophobia, with longer usage associated with higher prevalence53. Nomophobia is also correlated with individual stress levels and physical activity frequency54,55.

For covariate measurement, gender was recorded as a binary variable, with male coded as 0 and female as 1. Family background categories included: intact family = 1, remarried family = 2, single-parent family = 3, and other = 4. Academic year was coded as first-year = 1, fourth-year = 4, and graduate = 5, while major was classified as natural sciences = 1, medical sciences = 2, humanities and social sciences = 3, agricultural sciences = 4, and engineering and technology sciences = 5. Daily smartphone usage was assessed based on the average daily usage over the past month56. The frequency of weekly exercise was determined by inquiring about the average sessions per week (e.g., running, skipping, engaging in sports) within the past month. Academic stress was evaluated by asking if participants felt academic pressure during the current semester, with responses coded as “yes” = 1 and “no” = 0.

Data analysis

This study conducted basic descriptive analyses using SPSS 27.0 and tested hypotheses through path analysis in Mplus 8.0. To ensure robustness, maximum likelihood estimation was employed, along with 5,000 bootstrap samples for bias-corrected adjustments. The mediation effects were assessed via bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals (BCa CI). Statistical significance was indicated if the 95% confidence interval excluded zero57. The path analysis proceeded in two steps: first, examining the overall effect of social avoidance on nomophobia (Model 1), and then adding loneliness and self-control to test for parallel mediation effects (Model 2). Model fit was assessed using the Chi-square test (χ2/df), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis’s index (TLI), standardized root mean-square residual (SRMR), and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). A good fit was indicated by CFI and TLI values ≥ 0.90 and RMSEA and SRMR values ≤ 0.0858.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The primary characteristics of the 1,008 participants are summarized in Table 1. The participants had an average age of 20.12 years (SD = 2.22), with ages ranging from 16 to 35 years, and with nearly equal proportions of males (48.02%) and females (51.98%). The majority of participants were freshmen (61.11%) and majored in engineering and technological sciences (46.13%). Most participants reported living in intact two-parent families (87.50%). Regarding smartphone usage, approximately half of the participants (50.30%) reported using their smartphones for 5–8 h per day, while 25.20% used their phones for 9–12 h daily. Most participants (76.79%) had a monthly living cost between 1,000 and < 2,000 CNY, and 78.37% reported experiencing academic pressure. Regarding physical activity, 39.58% of participants exercised 2–3 times per week, while 22.62% exercised 4–5 times weekly. The mean scores for the key study variables were as follows: social avoidance (Mean = 6.77, SD = 3.70), loneliness (Mean = 16.29, SD = 4.13), self-control (Mean = 39.91, SD = 6.52), and nomophobia (Mean = 58.99, SD = 22.65).

Mediating role of loneliness and self-control

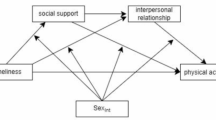

Path analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between social avoidance and nomophobia, with loneliness and self-control as mediators. The initial model, which tested the direct association between social avoidance and nomophobia, demonstrated good fit to the data: χ2 (5) = 31.417, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.072, CFI = 0.991, TLI = 0.983, and SRMR = 0.015. Results showed that social avoidance was significantly and positively associated with nomophobia (β = 0.336, p < 0.001). A parallel mediation model was then tested to explore the roles of loneliness and self-control as mediators. The mediation model (Fig. 1) also showed good fit: χ2 (45) = 231.543, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.064, CFI = 0.953, TLI = 0.909, and SRMR = 0.036. Path analysis revealed that social avoidance was positively associated with loneliness (β = 0.343, p < 0.001) and negatively associated with self-control (β = −0.316, p < 0.001). In turn, loneliness was positively associated with nomophobia (β = 0.210, p < 0.001), while self-control was negatively associated with nomophobia (β = −0.240, p < 0.001). The indirect effect of social avoidance on nomophobia through loneliness was β = 0.072 (p < 0.001), and through self-control, it was β = 0.076 (p < 0.001), with a total indirect effect of β = 0.148 (p < 0.001). Importantly, the inclusion of loneliness and self-control as mediators reduced the direct effect of social avoidance on nomophobia from β = 0.336 (p < 0.001) in the initial model to β = 0.108 (p < 0.001) in the mediation model, indicating partial mediation. The difference between the two mediating effects was not significant (Δβ = −0.004, p = 0.833), suggesting that loneliness and self-control contributed similarly to the relationship between social avoidance and nomophobia. These findings highlight that loneliness and self-control partially account for the association between social avoidance and nomophobia, while a significant direct effect remains.

Final model of the parallel mediating role of loneliness, self-control in the relationship between social avoidance and nomophobia. Standardized coefficients are reported. Mediating effects are reported in the bottom right of the figure; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed); DDSU: Duration of daily smartphone usage; MLC: monthly living costs.

Discussion

This study explored the mediating roles of loneliness and self-control in the relationship between social avoidance and nomophobia among Chinese college students. The results demonstrated that social avoidance is directly and positively associated with nomophobia, and that loneliness and self-control function as significant parallel mediators in this relationship. These findings provide a foundation for understanding the psychological mechanisms linking social avoidance to nomophobia and are further elaborated in this discussion.

The findings align with previous empirical evidence8,34,51, which suggest that social avoidance is associated with increased loneliness, thereby raising the risk of nomophobia. From a personality perspective, introverts often derive energy from their inner world, and real-world social interactions can deplete this energy, making social avoidance a protective mechanism59. Although avoidance behavior may temporarily reduce psychological stress, prolonged lack of social interaction likely intensifies loneliness60. To alleviate loneliness without depleting energy, smartphones become a vital tool for maintaining an internal-external balance. However, frequent smartphone use heightens the risk of nomophobia. In China’s collectivist culture, social interaction represents group belonging and social responsibility. Social avoidance, therefore, leads not only to emotional loneliness but also to unmet cultural expectations and social pressures35. In other words, in the Chinese context, social avoidance may not only reflect individual withdrawal but also trigger social judgment or disapproval from peers and family members, thereby intensifying psychological stress and internal conflict. In such situations, reliance on smartphone use offers a convenient means of avoiding social pressure.

Additionally, the results indicate that social avoidance may increase the risk of nomophobia by diminishing individuals’ self-control abilities. Socially avoidant individuals often lack experience and skills in interacting with the external world, making them more prone to negative emotions in social situations61. Self-control largely depends on emotional regulation. Current research suggests that when individuals cannot effectively manage negative emotions, they often resort to immediate gratification or distractions to alleviate discomfort, which further weakens their self-control abilities62. A cross-national study on self-control, emotional dysregulation, and the mediating effects of smartphone use on nomophobia shows that long-term reliance on smartphones as an emotional regulation tool undermines individuals’ capacity to cope with real-world stress, thereby diminishing their emotional regulation and self-control abilities63. When such individuals suddenly lose access to their phones or cannot use them, they experience heightened anxiety and are more susceptible to nomophobia. Furthermore, Mayorga-Muñoz et al.64 report that family-centric environments increase individuals’ dependency on familial support, reducing their external social interactions and leading to symptoms such as anxiety and discomfort in social settings. To alleviate these symptoms, they often use smartphones to maintain contact with the outside world, further weakening self-control and increasing the risk of nomophobia. These findings align with Self-Determination Theory’s views on autonomy and competence23.

It is noteworthy that in this study, the mediating effects of loneliness and self-control in the relationship between social avoidance and nomophobia were both statistically significant. However, the effect size of these two mediators did not differ significantly. This suggests that loneliness and self-control contribute similarly to the relationship between social avoidance and nomophobia, even though they operate through distinct psychological pathways65. In other words, although loneliness and self-control affect behavior through different pathways, they both serve similar compensatory roles in coping with the psychological stress associated with social avoidance. Specifically, loneliness triggers a desire for social connection, while decreased self-control leads to greater immersion in smartphone use. For instance, in a study on social exclusion and nomophobia, Yue et al.66 found that loneliness significantly increases dependence on smartphones, whereas social exclusion weakens self-control, making it difficult for individuals to resist the impulse to use smartphones. Both psychological states in why their mediating effects did not differ significantly in statistical analysis. Future research could explore the interaction or potential interplay between these two mediators to further understand how they jointly influence individuals’ psychological states and behaviors.

Importantly, the inclusion of loneliness and self-control as mediators notably weakened the direct association between social avoidance and nomophobia, suggesting partial mediation. This finding suggests that while loneliness and self-control play crucial roles in explaining the relationship between social avoidance and nomophobia, they do not fully account for it. The reduction in the direct effect highlights the importance of these mediators, but also indicates that other unexplored factors may contribute to the relationship. This is consistent with the compensatory internet use theory67, which suggests that individuals may rely on digital devices not only to cope with emotional distress but also due to insufficient coping resources, such as limited social competence and lack of social interaction stimuli in real life. Variables such as emotion regulation, social support, or resilience might also play significant roles and warrant further investigation in future studies.

The results of this research carry significant implications for developing targeted interventions. First, this study has identified loneliness as a key factor linking social avoidance and nomophobia. This highlights the importance of increasing the frequency of social interactions and providing social skills training. Group activities or group-based interventions can offer college students valuable opportunities for interpersonal interaction, mutual feedback, and emotional support, which are essential for enhancing their social skills and interpersonal engagement68. A literature review by Ellard et al.69 screened 182 studies and identified 28 interventions after assessing risk of bias; of these, 28 were implemented in group settings. Using the revised UCLA Loneliness Scale to assess their effectiveness, results showed that about two-thirds of the interventions significantly reduced loneliness. Moreover, a randomized controlled trial by Yildiz and Duyan68 found that a five-session group social skills training for college students effectively reduced loneliness. Accordingly, social workers and university health educators could, therefore, implement structured group interventions to enhance students’ social competencies, facilitate peer support systems, and mitigate loneliness.

Second, as self-control serves as an indirect mechanism between social avoidance and nomophobia, enhancing emotion regulation may be an effective strategy for improving self-control. For example, previous studies have shown that poor self-control is associated with impulsive behavioral problems such as nomophobia26. Emotion regulation theory also suggests that training can help individuals better manage emotional responses, thereby enhancing self-control70. Mindfulness, regarded as a form of self-regulation, emphasizes consciously perceiving and focusing attention on the present moment, which can help students identify and regulate impulsive behaviors. Empirical research has also confirmed that mindfulness training can increase self-control among college students, thereby reducing smartphone addiction behaviors71. Moreover, according to self-determination theory, acceptance and encouragement from others fulfill individuals’ basic need for relatedness, thereby enhancing their self-regulatory resources. When social support is lacking, individuals may be more likely to avoid social interactions. In contrast, adequate social support can promote greater engagement in social activities and satisfy the need for connectedness. Moreover, higher levels of social support may facilitate the management and restoration of self-control resources, strengthening individuals’ capacity to resist impulses and temptations72. Therefore, increasing opportunities for social interaction and fostering supportive social networks may enhance college students’ self-control and, in turn, alleviate symptoms of nomophobia.

Limitation and future study

Despite offering valuable insights, this study has limitations. First, although the present study identified social avoidance as a potential predictor of nomophobia, the reverse relationship may also be plausible. Given the cross-sectional design of this study, this cannot be tested; therefore, future research is recommended to adopt a longitudinal design to verify the causal relationship. Second, while the mediating effects of loneliness and self-control were statistically significant, the effect sizes were relatively small. This suggests that these mediators only partially explain the relationship between social avoidance and nomophobia. Future research should explore additional mediators, such as emotion regulation, social support, and resilience, to better understand the mechanisms underlying nomophobia. Third, the sample focused primarily on Chinese college students, which may impact the generalizability of the findings. Future research could include diverse cultural and age groups to validate these relationships.

Conclusion

This study examined the associations between social avoidance, loneliness, self-control, and nomophobia among Chinese college students. The findings indicate that loneliness and self-control act as mediators, providing insights into the mechanisms underlying nomophobia. These results contribute to the theoretical understanding of nomophobia and suggest potential practical approaches for improving the psychological well-being of college students. Specifically, the findings suggest the potential value of intervention strategies aimed at enhancing students’ social skills and self-management abilities. Future research should further explore additional mediators and moderators to build a more comprehensive understanding of nomophobia and its underlying factors.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns for participants but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yildirim, C. Exploring the Dimensions of Nomophobia: Developing and Validating a Questionnaire Using Mixed Methods Research (Iowa State University, 2014).

China Internet Network Information Center. The 54th Statistical Report on the Development of the Internet in China. https://www.cnnic.cn/n4/2024/0828/c208-11063.html. Accessed 29 Aug 2024.

Secur Envoy. 66% of the population suffer from nomophobia: The fear of being without their phone. Secur. Envoy Blog. https://www.securenvoy.com/blog/2012/02/16/66-of-the-population-suffer-from-nomophobia-the-fear-of-being-without-their-phone/ (2012).

Tams, S., Legoux, R. & Léger, P. M. Smartphone withdrawal creates stress: A moderated mediation model of nomophobia, social threat, and phone withdrawal context. Comput. Hum. Behav. 81, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.11.026 (2018).

Çiçek, I., Emin, Ş. M., Arslan, G. & Yıldırım, M. Problematic social media use, satisfaction with life, and levels of depressive symptoms in university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: mediation role of social support. Psihologija 57 (2), 177–197. https://doi.org/10.2298/PSI220613009C (2024).

Durak, H. Y. Investigation of nomophobia and smartphone addiction predictors among adolescents in turkey: demographic variables and academic performance. Social Sci. J. 56 (4), 492–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2018.09.003 (2019).

Kurnia, E. A., Satiadarma, M. P. & Wati, L. The relationship between nomophobia and poorer sleep among college students. In International Conference on Economics, Business, Social, and Humanities, Atlantis Press, 1254–1261. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.210805.196 (2021).

Zhang, X. F., Gao, F. Q., Geng, J. Y., Wang, Y. M. & Han, L. Social avoidance and distress and mobile phone addiction: A multiple mediating model. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 26 (3), 494–497. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2018.03.017 (2018).

Jiang, Y. et al. Social anxiety, loneliness, and mobile phone addiction among nursing students: Latent profile and moderated mediation analyses.BMC Nurs. 23(1), 905. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02583-8 (2024).

China Youth Daily. Over 80% of surveyed university students consider themselves mildly socially anxious. In Reprinted in The Paper. https://m.thepaper.cn/baijiahao_15509805 (2021).

Gao, J. X., Jin, T. L. & Wuyun, T. A cross-temporal meta-analysis of changes in social anxiety among Chinese college students. Chin. J. Social Psychol. Rev. 2, 240–256 (2024). 264-265.

Shang, A., Feng, L., Yan, G. & Sun, L. The relationship between self-esteem and social avoidance among university students: chain mediating effects of resilience and social distress. BMC Psychol. 13 (1), 116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-02444-2 (2025).

Moran, V. E., Abbá, C., Natera, M. Z., Villarrubia, M. D. & Curi, M. V. Social avoidance scale for university students (SAS-U): Development and preliminary validation. J. Coll. Student Mental Health. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/28367138.2025.2491516 (2025).

Carver, C. S. & Scheier, M. F. Control theory: A useful conceptual framework for personality–social, clinical, and health psychology. Psychol. Bull. 92 (1), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.92.1.111 (1982).

Bagozzi, R. P. The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Social Psychol. Q. 55, 178–204 (1992).

Çiçek, İ. Mediating role of self-esteem in the association between loneliness and psychological and subjective well-being in university students. Int. J. Contemp. Educational Res. 8 (2), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.33200/ijcer.817660 (2021).

Lim, M. H., Rodebaugh, T. L., Zyphur, M. J. & Gleeson, J. F. Loneliness over time: the crucial role of social anxiety. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 125 (5), 620. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000162 (2016).

Gross, J. J. Emotion regulation: affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology 39 (3), 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0048577201393198 (2002).

Akyol Güner, T. & Demir, İ. Relationship between smartphone addiction and nomophobia, anxiety, self-control in high school students. Addicta 9 (2) (2022).

Duckworth, A. L., Taxer, J. L., Eskreis-Winkler, L., Galla, B. M. & Gross, J. J. Self-control and academic achievement. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 70 (1), 373–399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103230 (2019).

Lapierre, M. A., Zhao, P. & Custer, B. E. Short-term longitudinal relationships between smartphone use/dependency and psychological well-being among late adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health. 65 (5), 607–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.06.001 (2019).

Cacioppo, J. T. et al. Loneliness across phylogeny and a call for comparative studies and animal models. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10 (2), 202–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614564876 (2015).

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55 (1), 68. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68 (2000).

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer Sci. Bus. Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7 (2013).

Muraven, M., Tice, D. M. & Baumeister, R. F. Self-control as a limited resource: regulatory depletion patterns. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 74 (3), 774–789. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.774 (1998).

Safaria, T., Saputra, N. E. & Arini, D. P. The impact of nomophobia: exploring the interplay between loneliness, smartphone usage, self-control, emotion regulation, and spiritual meaningfulness in an Indonesian context. J. Technol. Behav. Sci., 1–20 (2024).

Preacher, K. J. & Hayes, A. F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods. 40 (3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 (2008).

Li, B. Analysis of the characteristics of contemporary youth online social mobility. China Youth Study. 333 (11), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-9931.2023.11.004 (2023).

Luo, Y. F. & Ye, L. Y. Socialising in the post 00 internet generation: dependence in the cyber circle and alienation in the blood circle. Media Sci. Technol. China. 358 (01), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.19483/j.cnki.11-4653/n.2023.01.004 (2023).

Pan, S. Y. & Liu, Y. Examining the effect of WeChat usage on the social capital among Chinese college students. Chin. J. Journalism Communication. 40 (04), 126–143. https://doi.org/10.13495/j.cnki.cjjc.2018.04.007 (2018).

Akkın Gürbüz, H. G., Demir, T., Gökalp Özcan, B., Kadak, M. T. & Poyraz, B. Ç. Use of social network sites among depressed adolescents. Behav. Inform. Technol. 36 (5), 517–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2016.1262898 (2017).

Li, S., Ran, G. M., Zhang, Q., Chen, X. & Chen, J. Y. Relationship between social avoidance and internet overuse: A chain mediating model. Chin. J. Appl. Psychol. 26 (04), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-6020.2020.04.003 (2020).

Asendorpf, J. B. Beyond social withdrawal: shyness, unsociability, and peer avoidance. Hum. Dev. 33 (4–5), 250–259. https://doi.org/10.1159/000276522 (1990).

Taylor, H. O., Cudjoe, T. K., Bu, F. & Lim, M. H. The state of loneliness and social isolation research: current knowledge and future directions. BMC Public. Health. 23 (1), 1049. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15967-3 (2023).

Chen, X., Wang, L. & Wang, Z. Shyness-sensitivity and social, school, and psychological adjustment in rural migrant and urban children in China. Child Dev. 80 (5), 1499–1513. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01347.x (2009).

Bian, M. & Leung, L. Linking loneliness, shyness, smartphone addiction symptoms, and patterns of smartphone use to social capital. Social Sci. Comput. Rev. 33 (1), 61–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314528779 (2015).

Gezgin, D. M., Cakir, O. & Yildirim, S. The relationship between levels of nomophobia prevalence and internet addiction among high school students: the factors influencing nomophobia. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 4 (1), 215–225. https://doi.org/10.21890/ijres.383153 (2018).

Özdemir, B., Çakır, Ö. & Hussain, I. Prevalence of nomophobia among university students: A comparative study of Pakistani and Turkish undergraduate students. Eurasia J. Math. Sci.Technol. Educ.. 14 (4). https://doi.org/10.29333/ejmste/84839 (2018).

Tan, S. H. & Guo, Y. Y. A limited resource model of self-control and the relevant studies. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 16 (3), 309–311. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2008.03.029 (2008).

Partin, R. D., Stojakovic, N., Alqahtani, M., Meldrum, R. C. & Pires, S. F. Low self-control and environmental harm: A theoretical perspective and empirical test. Am. J. Criminal Justice. 45, 933–954. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-019-09514-3 (2020).

Günlü, A. & Bas, A. U. The mediating role of self-control in the relationship between nomophobia and basic psychological needs in university students. Int. J. Progressive Educ. 18 (6), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.29329/ijpe.2022.477.7 (2022).

Guo, Y. et al. COVID-19–related social isolation, self-control, and internet gaming disorder among Chinese university students: cross-sectional survey. J. Med. Internet. Res. 26, e52978. https://doi.org/10.2196/52978 (2024).

Safaria, T., Saputra, N. E. & Arini, D. P. The impact of nomophobia: exploring the interplay between loneliness, smartphone usage, self-control, emotion regulation, and spiritual meaningfulness in an Indonesian context. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-024-00438-2 (2024).

Ren, S. X., GuLi, G. N. & Liu, T. Revision of the Chinese version of the nomophobia scale. Psychol. Explor. 40 (3), 247–253 (2020).

Heng, S. P., Zhao, H. F. & Zhou, Z. K. Nomophobia: Why we can’t separate ourselves from our phones? Psychol. Dev. Educ. 39 (1), 140–152. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2023.01.15 (2023).

Chen, J. J., Fang, X. H. & Zhang, K. Effect of attachment anxiety on nomophobia in college students: chain mediating effect. China J. Health Psychol. 31 (11), 1747–1752. https://doi.org/10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2023.11.027 (2023).

Liu, Y. Y., Fu, C. Q. & Ran, J. The relationship between neuroticism and nomophobia in medical students: the mediating effect of fear of missing out. China J. Health Psychol. 32 (1), 138–143. https://doi.org/10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2024.01.025 (2024).

Watson, D. & Friend, R. Measurement of social-evaluative anxiety. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 33 (4), 448. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0027806 (1969).

Hays, R. D. & DiMatteo, M. R. A short-form measure of loneliness. J. Pers. Assess. 51 (1), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5101_6 (1987).

Russell, D., Peplau, L. A. & Cutrona, C. E. The revised UCLA loneliness scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 39 (3), 472. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472 (1980).

Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F. & Boone, A. L. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J. Pers. 72 (2), 271–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x (2004).

Daei, A., Ashrafi-Rizi, H. & Soleymani, M. R. Nomophobia and health hazards: smartphone use and addiction among university students. Int. J. Prev. Med. 10 (1), 202. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_184_19 (2019).

Kaviani, F., Robards, B., Young, K. L. & Koppel, S. Nomophobia: Is the fear of being without a smartphone associated with problematic use? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17 (17), 6024. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176024 (2020).

Buctot, D. B., Kim, N. & Kim, S. H. The role of nomophobia and smartphone addiction in the lifestyle profiles of junior and senior high school students in the Philippines. Social Sci. Humanit. Open. 2 (1), 100035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100035 (2020).

Kateb, S. A. The prevalence and psychological symptoms of nomophobia among university students. J. Res. Curriculum Instruction Educational Technol. 3 (3), 155–182. https://doi.org/10.21608/jrciet.2017.24454 (2017).

Cha, J. H., Choi, Y. J., Ryu, S. & Moon, J. H. Association between smartphone usage and health outcomes of adolescents: A propensity analysis using the Korea youth risk behavior survey. PLOS One. 18 (12), e0294553. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0294553 (2023).

Fang, J., Zhang, M. Q. & Qiu, H. Z. Methods of testing for mediation effects and effect size measurement: A review and outlook. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 28 (1), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2012.01.015 (2012).

Bollen, K. A. & Curran, P. J. Latent curve models: A structural equation perspective. John Wiley Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471746096 (2006).

Wei, M. Social distancing and lockdown–an introvert’s paradise? An empirical investigation on the association between introversion and the psychological impact of COVID-19-related circumstantial changes. Front. Psychol. 11, 561609. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.561609 (2020).

Lieberz, J. et al. Behavioral and neural dissociation of social anxiety and loneliness. J. Neurosci. 42 (12), 2570–2583. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2029-21.2022 (2022).

Valenti, G. D., Bottaro, R. & Faraci, P. Effects of difficulty in handling emotions and social interactions on nomophobia: examining the mediating role of feelings of loneliness. Int. J. Mental Health Addict. 22 (1), 528–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00888-w (2024).

Park, S., Kang, M. & Kim, E. Social relationship on problematic internet use (PIU) among adolescents in South korea: A moderated mediation model of self-esteem and self-control. Comput. Hum. Behav. 38, 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.06.005 (2014).

Safaria, T., Wahab, M. N. A., Suyono, H. & Hartanto, D. Smartphone use as a mediator of self-control and emotional dysregulation in nomophobia: A cross-national study of Indonesia and Malaysia. Psikohumaniora: Jurnal Penelitian Psikologi. 9 (1), 37–58. https://doi.org/10.21580/pjpp.v9i1.20740 (2024).

Mayorga-Muñoz, C., Riquelme-Segura, L., Delvecchio, E. & Lee-Maturana, S. Association between familism and mental health in college adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 20 (5), 4149. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054149 (2023).

Nguyen, B. T. N., Nguyen, N. P. H., Hoang, H. T., Nguyen, Q. A. N. & Le, U. T. T. The role of loneliness and self-control to the association between nomophobia and depression symptoms among Vietnamese high school students. SSRN 4271363. https://doi.org/10.54615/2231-7805.47308 (2023).

Yue, H., Yue, X., Zhang, X., Liu, B. & Bao, H. Exploring the relationship between social exclusion and smartphone addiction: the mediating roles of loneliness and self-control. Front. Psychol. 13, 945631. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.945631 (2022).

Kardefelt-Winther, D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 31, 351–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059 (2014).

Yildiz, H. & Duyan, V. Effect of group work on coping with loneliness. Social Work Groups. 45 (2), 132–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/01609513.2021.1990192 (2022).

Ellard, O. B., Dennison, C. & Tuomainen, H. Interventions addressing loneliness amongst university students: A systematic review. Child Adolesc. Mental Health. 28 (4), 512–523. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12614 (2023).

Gross, J. J. Emotion regulation. Handb. Emotions. 3 (3), 497–513 (2008). https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2007-01392-001

Cheng, S. S., Zhang, C. Q. & Wu, J. Q. Mindfulness and smartphone addiction before going to sleep among college students: the mediating roles of self-control and rumination. Clocks Sleep. 2 (3), 354–363. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep2030026 (2020).

Zhong, G. et al. The relationship between social support and smartphone. Addiction: the mediating role of negative emotions and self-control. BMC Psychiatry. 25, 167. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-025-06615-8 (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Huishan He was primarily responsible for data collection and drafting the manuscript. Juanjuan Wang led the study design, conducted statistical analyses, and managed manuscript revisions and corrections. All authors contributed to the study’s conceptualization, data interpretation, and critical review of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, H., Wang, J. The roles of loneliness and self-control in the association between social avoidance and nomophobia among college students. Sci Rep 15, 26782 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10789-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10789-2