Abstract

We aimed to evaluate the clinical-imaging diversity of exudative pulmonary cryptococcosis (PC) with different immune states. The clinical and imaging data of 76 patients with PC (immunocompetent exudative PC 36 cases and immunocompromised exudative PC 40 cases) were respectively reviewed to determine the diagnostic features. Immunocompromised exudative PC was more often with bilateral distribution (30.6% vs. 80.0%, P < 0.001), ground-glass reticular pattern (13.9% vs. 52.5%, P < 0.001), mediastinal lymphadenopathy (0 vs. 20.0%, P = 0.014) and pleural effusion (0 vs. 22.5%, P = 0.007). The inflammatory response (66.7% vs. 20.0%, P < 0.001) and perifissural consolidation (52.8% vs. 12.5%, P < 0.001) were more common in immunocompetent exudative PC. The exudative PC had diverse clinical and imaging findings under different immune states. Inflammatory response, perifissural consolidation, bilateral distribution, ground-glass reticular pattern, mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and pleural effusion could suggest exudative PC with different immune states and provide reliable evidence for clinical diagnosis and treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pulmonary cryptococcosis (PC) is a fungal infection that often affects immunocompromised individuals1. Recent data showed that the incidence of immunocompetent PC is increasing on the Chinese mainland2. Due to different immune states and inflammatory responses, the clinical and imaging findings of PC are complex3. Although nodule is the most common morphological type of PC, pneumonia-type changes are not rare in recent decades4,5,6. Depending on the immune state and clinical course, PC can exhibit exudative infiltration5,6. On CT imaging, exudative PC predominantly manifests as ground-glass opacity or patchy consolidation7,8. It is important to recognize its diversity for clinical diagnosis. Nodular PC and exudative PC represent different stages of infection3,4,5,6. Nodular PC is the stable granuloma formation. Exudative changes are more common in early PC, and with clinical severity. Previous studies showed that the different immune states affect the clinical and imaging findings of nodular PC. Immunocompromised nodular PC was more common with cavity and halo sign1,2,3. However, the relationship between immune states and exudative PC is unclear. Moreover, exudative PC is often misdiagnosed as community-acquired pneumonia, causing a delay in antifungal treatment. Therefore, correct diagnosis of exudative PC with different immune states is crucial for its timely and rational intervention. To our knowledge, no comprehensive clinical-imaging analysis concentrated on exudative PC. Hence, this study will investigate its clinical and imaging features under different immune states to improve clinical diagnosis and treatment.

Materials and methods

Clinical data

This study was designed and conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committees of Affiliated Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital of Qingdao University (No. 2023 − 275) and Affiliated Hospital of Yangzhou University (No. 2023-YKL07). Because it was a retrospective study, the Ethics Committees of Affiliated Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital of Qingdao University and Affiliated Hospital of Yangzhou University waived the requirement to obtain informed consent from the study participants. From May 2012 to November 2023, clinical and imaging data were collected from 160 patients with PC. Based on the CT findings at the first examination, exudative PC was defined as the patchy opacities with or without complete obstruction of the underlying bronchial and vascular structures. The inclusion criteria: exudative CT findings, definite pathological diagnosis, positive cryptococcal antigen (CrAg, colloidal gold labeled) with appropriate clinical symptoms, or positive etiological culture of Cryptococcus. The exclusion criteria: typical nodular PC, incomplete clinical and imaging data, comorbid with other pulmonary lesions, or pulmonary infection with other pathogens. A typical nodular PC was a well-defined round opacity with an average diameter ≤ 3 cm. Patients with one of the following conditions were considered as immunocompromised individuals. Clinical indicators: use of immunosuppressants or glucocorticoids (systemic glucocorticoids therapy, 0.2-1.0 mg/kg/d based on prednisone with duration > 3 months or lifelong replacement therapy, excluding inhaled glucocorticoids therapy), malignancies during radiochemotherapy (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy), immunosuppressive diseases (AIDS, nephrotic syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren’s syndrome, ankylosing spondylitis, etc.), organ transplantation, neutropenia (peripheral absolute neutrophil count < 2.0 × 109 cells/L) or lymphopenia (absolute lymphocyte count < 1,000 cells/µL)1,9. Humoral immune indicators: serum immunoglobulin IgG < 7.0 g/L, IgA < 0.4 g/L, or IgM < 0.7 g/L. Cellular immune indicators: the percentage of CD3 cells < 60%, the percentage of CD4 cells < 24.5%, the percentage of CD8 cells < 18.5%, or CD4/CD8 ratio < 1.021,9. Immunocompetent individuals did not have these potential risk factors. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 73 cases of typical nodular PC and 11 cases of exudative PC (5 cases with incomplete clinical imaging data, 4 cases with other pathogenic infections, and 2 cases with other pulmonary lesions) were ultimately excluded. Eventually, 76 patients with exudative PC were divided into the immunocompetent exudative PC group (36 cases) and the immunocompromised exudative PC group (40 cases). See Fig. 1 for details. Their clinical and imaging data were retrospectively analyzed. The inflammatory response was evaluated by white blood cell (WBC) count, neutrophil (NE) count, neutrophil percentage (NE%), and C-reactive protein (CRP). WBC count > 10 × 109/L, NE count > 7 × 109/L, NE% > 70%, or CRP > 8.2 mg/L referred to the inflammatory response1,9. Environmental exposure included poultry and pet keeping (especially pigeons), soil excavation, humid conditions, fieldwork, etc1. Routine tests (appearance, specific gravity, Rivalta test, cytological count and classification), biochemistry analysis, and fungal culture of pleural effusions were performed.

Imaging evaluations

Before treatment, all 76 patients underwent non-enhanced CT scans (16- or 64-section CT scanner, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, USA) and were evaluated on the Medcare AnyImage workstation (V4.5). Imaging indicators included the distribution of lesions (unilateral or bilateral distribution), CT signs (halo sign, ground-glass reticular pattern, and perifissural consolidation), pleural abnormalities (pleural-based involvement or pleural effusion), and mediastinal lymphadenopathy10. A rim of ground-glass opacity surrounding the lesion was defined as the halo sign. The ground-glass reticular pattern was defined as the variable combinations of ground-glass and reticular opacities without complete obscuration of the underlying bronchial and vascular structures. Consolidation was defined as the increased attenuation of opacity with complete obscuration of the underlying bronchial and vascular structures. The consolidation that had direct contact with the fissure, but did not arise from it, should be called perifissural consolidation. The lesion that contacted the pleura, but did not arise from it, was defined as pleura-based involvement. See Supplementary Fig. 1 for details. A lymph node with a short axis diameter ≥ 10 mm was considered lymphadenopathy. Two thoracic radiologists (with more than 10 years of experience) who were unaware of the final diagnoses assessed all imaging data independently. In the case of disagreement, consensus should be reached through consultation.

Statistical analysis

By IBM SPSS version 26.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL), descriptive statistics were used to characterize the clinical and imaging findings of both groups. All data were presented as numbers (n) or mean ± SD. Different statistical tests were adopted according to the data type. An independent t-test (two-tailed) or Mann-Whitney U test was performed to compare continuous variables between the two groups. The Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) was used to assess the difference between dichotomous variables. For the inter-observer variability of CT analyses, interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) > 0.75 or Kappa ≥ 0.8 was considered a better agreement. P < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Results

Clinical-imaging findings

For imaging analyses, the inter-observer agreements between the two observers were good (ICC = 0.8623, Kappa = 0.8531). There was no difference in age, sex, clinical symptoms, environmental exposure, and pleural-based involvement between the two groups (P = 0.468, P = 0.483, P = 0.426, P = 0.604, and P = 0.258, respectively). The clinical symptoms were nonspecific, including cough, expectoration, chest distress, chest pain, fever, etc. Nine cases with immunocompromised exudative PC had pleural effusions. The routine tests and biochemistry examinations of pleural effusions showed that all nine cases were exudative. Among them, seven cases underwent cryptococcal culture of pleural effusion, and two cases were positive.

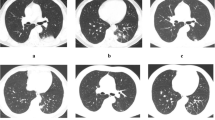

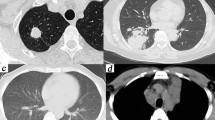

The inflammatory response (66.7% vs. 20.0%, P < 0.001) and perifissural consolidation (52.8% vs. 12.5%, P < 0.001) were more common in immunocompetent exudative PC. Immunocompromised exudative PC was more often with bilateral distribution (30.6% vs. 80.0%, P < 0.001), ground-glass reticular pattern (13.9% vs. 52.5%, P < 0.001), pleural effusion (0 vs. 22.5%, P = 0.007), and mediastinal lymphadenopathy (0 vs. 20.0%, P = 0.014). See Table 1; Figs. 2 and 3 for details.

CT findings of immunocompetent exudative PC. Axial CT image showed patchy consolidation in the left lower lobe with pleural-based involvement (a). Patchy consolidation with pleural-based involvement and halo sign occurred in the right lower lobe on axial CT (b). Axial CT image showed perifissural consolidation in the right lower lobe (c). Multiple patchy solid opacities with perifissural consolidation and halo signs occurred in the right upper and lower lobes on axial CT (d).

CT findings of immunocompromised exudative PC. Axial CT images showed bilateral diffuse ground-glass opacities and consolidations (a) with mediastinal lymphadenopathy (b). Bilateral ground-glass reticular opacities (c), pleural effusions, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy (d) were displayed on axial CT. Axial CT image showed bilateral ground-glass reticular opacities with pleural-based involvement (e). Bilateral ground-glass opacities and consolidations were displayed on axial CT (f).

Discussion

This study found that the clinical-imaging findings of exudative PC were diverse under different immune states. Inflammatory response and perifissural consolidation suggested the immunocompetent exudative PC. Bilateral distribution, ground-glass reticular pattern, pleural effusion, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy suggested the immunocompromised exudative PC. A combination of these clinical and imaging features revealed the diversity of exudative PC.

There was no difference in age, sex, clinical symptoms, and environmental exposure between the two groups. Clinically, some PC patients have no environmental exposure and sex differences11,12. The spread of Cryptococcus is determined by PH value, humidity, temperature, sunlight, and wind13,14. Environmental exposure should be carefully considered in clinical diagnosis. High-risk environmental exposure supports the diagnosis of PC, but the interaction between host and pathogen plays a key role in pathogenesis15. Cryptococcal infection and pulmonary involvement may bring about nonspecific clinical symptoms. With the popularity of physical examination and chest CT, asymptomatic PC is becoming more common in clinical practice. PC patients without clinical symptoms should be taken seriously. However, the immune state is related to the inflammatory degree16. The inflammatory response of immunocompetent exudative PC represented the elevated host defense. Conversely, a low immune activity could weaken the inflammatory response17.

Previous studies found that immunocompromised patients are more common with exudative changes in the subpleural area18,19. However, both the inflammatory response of immunocompetent PC and cryptococcal dissemination of immunocompromised PC could contribute to exudative changes18,19. Due to the low immune activity of immunocompromised PC, partial filling of alveoli by cryptococcal spores and mucinous degeneration induced ground-glass opacities19,20. An active inflammatory response of immunocompetent PC resulted in exudative consolidation20,21. Without immune protection, immunocompromised individuals could not limit cryptococcal distribution in the respiratory system22,23. The dissemination along the lymphatic vessels caused reticular changes and mediastinal lymphadenopathy24,25. Moreover, interstitial involvement further increased the bilateral involvement of PC26,27. On the contrary, the immunocompetent state reduced cryptococcal dissemination with unilateral distribution28. PC distribution was random after airway inhalation, and only the site with high cryptococcal load caused inflammatory changes28,29. Immunocompetent patients could confine the PC lesions to one lobe through perifissural consolidation30. Because of the suitable temperature and nutritional state in the subpleural areas, pleural-based involvement was common in both groups31. However, immunocompromised exudative PC could damage pleural-airway integrity and cause pleural effusion24,32. In this study, all nine cases had exudative pleural effusions, suggesting cryptococcal invasiveness. Due to cryptococcal invasion or inflammatory infiltration, the halo signs in both groups indicated coagulative necrosis, alveolar hemorrhage, or serious exudation surrounding the lesion33.

Combining clinical and imaging features provided more meaningful diagnostic information. The inflammatory response was positive feedback from immunocompetent individuals to control cryptococcal infection13,34. Perifissural consolidation was the corresponding CT findings, without excessive dissemination. For immunocompromised individuals, bilateral distribution, ground-glass reticular pattern, pleural effusion, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy reflected cryptococcal invasion and dissemination13,34. The mechanism of exudative PC with different immune states is too complex to explain by a single feature. It is necessary to integrate multiple clinical-imaging factors for comprehensive evaluation.

Due to the difficulty in culturing Cryptococcus, few patients in this study were diagnosed with the Cryptococcus subtype. Fortunately, the treatment for Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii is similar35. The lack of uniformity in immune evaluation is the current challenge. Retrospective single-center studies with a smaller sample size inevitably resulted in selection bias and confounding factors. Longitudinal multi-center studies with refined immune assessment should be performed in the future.

Conclusion

In this study, we identified the diversity of exudative PC with different immune states through clinical and imaging comparisons. For immunocompromised exudative PC, bilateral distribution, ground-glass reticular pattern, pleural effusion, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy suggested cryptococcal invasion and dissemination. For immunocompetent exudative PC, inflammatory response and perifissural consolidation reflected the immune resistance against PC. These clinical and imaging features could provide some reliable evidence for subsequent CrAg tests and antifungal therapy.

Data in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Data availability

Data in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Zhang, Y. et al. Clinical analysis of 76 patients pathologically diagnosed with pulmonary cryptococcosis. Eur. Respir J. 40 (5), 1191–1200 (2012).

Setianingrum, F., Rautemaa-Richardson, R. & Denning, D. W. Pulmonary cryptococcosis: a review of pathobiology and clinical aspects. Med. Mycol. 57 (2), 133–150 (2019).

Chen, F., Liu, Y. B., Fu, B. J., Lv, F. J. & Chu, Z. G. Clinical and computed tomography (CT) characteristics of pulmonary nodules caused by Cryptococcal infection. Infect. Drug Resist. 14, 4227–4235 (2021).

Nadrous, H. F., Antonios, V. S., Terrell, C. L. & Ryu, J. H. Pulmonary cryptococcosis in nonimmunocompromised patients. Chest 124 (6), 2143–2147 (2003).

Kiertiburanakul, S., Wirojtananugoon, S., Pracharktam, R. & Sungkanuparph, S. Cryptococcosis in human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 10, 72–78 (2006).

Chang, C. C., Sorrell, T. C. & Chen, S. C. Pulmonary cryptococcosis. Semin Respir Crit. Care Med. 36, 681–691 (2015).

Xinqiang, G., Hongxia, Z., Wenmin, H. & Hui, W. Pulmonary cryptococcosis in non-HIV-infected individuals: HRCT characteristics in 58 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 103 (26), e38671 (2024).

Eremiev, S. et al. Pulmonary cryptococcosis mimicking lung Cancer. Open. Respir Arch. 4 (2), 100154 (2022).

Yan, Y. et al. Lesion size as a prognostic factor in the antifungal treatment of pulmonary cryptococcosis: a retrospective study with chest CT pictorial review of 2-year follow up. BMC Infect. Dis. 23 (1), 153 (2023).

Bankier, A. A. et al. Glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology 310 (2), e232558 (2024).

Hou, X. et al. Pulmonary cryptococcosis characteristics in immunocompetent patients-A 20-year clinical retrospective analysis in China. Mycoses 62, 937–944 (2019).

Galanis, E., Macdougall, L., Kidd, S., Morshed, M. & British Columbia Cryptococcus gattii Working Group. Epidemiology of Cryptococcus gattii, British columbia, canada, 1999–2007. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16, 251–257 (2010).

Secombe, C. J., Lester, G. D. & Krockenberger, M. B. Equine pulmonary cryptococcosis: A comparative literature review and evaluation of fluconazole monotherapy. Mycopathologia 182 (3–4), 413–423 (2017).

Chowdhary, A., Rhandhawa, H. S., Prakash, A. & Meis, J. F. Environmental prevalence of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus Gattii in india: an update. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 38 (1), 1–16 (2012).

Deng, H. et al. Clinical features and radiological characteristics of pulmonary cryptococcosis. J. Int. Med. Res. 46, 2687–2695 (2018).

Xie, L. X., Chen, Y. S., Liu, S. Y. & Shi, Y. X. Pulmonary cryptococcosis: comparison of CT findings in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients. Acta Radiol. 56, 447–453 (2015).

Qu, J., Zhang, X., Lu, Y., Liu, X. & Lv, X. Clinical analysis in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis in Western China. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 9387 (2020).

Choi, H. S., Kim, Y. H., Jeong, W. G., Lee, J. E. & Park, H. M. Clinicoradiological features of pulmonary cryptococcosis in immunocompetent patients. J. Korean Soc. Radiol. 84 (1), 253–262 (2023).

Xiong, P., Huang, C., Zhong, L. & Huang, L. Clinical and imaging characteristics of pulmonary cryptococcosis: a comparative analysis of 118 non-AIDS patients in China. Med. Mycol. 61 (3), myad019 (2023).

Yoon, H. A., Felsen, U., Wang, T. & Pirofski, L. A. Cryptococcus neoformans infection in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and HIVuninfected patients at an inner-city tertiary care hospital in the Bronx. Med. Mycol. 58, 434–443 (2020).

Hu, Y., Ren, S. Y., Xiao, P., Yu, F. L. & Liu, W. L. The clinical and radiological characteristics of pulmonary cryptococcosis in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients. BMC Pulm Med. 21, 1–7 (2021).

Wang, R. Y. et al. Cryptococcosis in patients with hematological diseases: a 14-year retrospective clinical analysis in a Chinese tertiary hospital. BMC Infect. Dis. 17 (1), 463 (2017).

Sui, X. et al. Clinical features of pulmonary cryptococcosis in thin-section CT in immunocompetent and non-AIDS immunocompromised patients. Radiol. Med. 125 (1), 31–38 (2020).

Zinck, S. E., Leung, A. N., Frost, M., Berry, G. J. & Müller, N. L. Pulmonary cryptococcosis: CT and pathologic findings. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 26, 330–334 (2002).

Xiong, C., Lu, J., Chen, T. & Xu, R. Comparison of the clinical manifestations and chest CT findings of pulmonary cryptococcosis in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 22 (1), 415 (2022).

Chang, W. C. et al. Pulmonary cryptococcosis: comparison of clinical and radiographic characteristics in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients. Chest 129 (2), 333–340 (2006).

Fang, L. F., Zhang, P. P., Wang, J., Yang, Q. & Qu, T. T. Clinical and Microbiological characteristics of cryptococcosis at an university hospital in China from 2013 to 2017. Braz J. Infect. Dis. 24 (1), 7–12 (2020).

Lindell, R. M., Hartman, T. E., Nadrous, H. F. & Ryu, J. H. Pulmonary cryptococcosis: CT findings in immunocompetent patients. Radiology 236 (1), 326–331 (2005).

Shi, J. et al. Retrospective analysis of pulmonary cryptococcosis and extrapulmonary cryptococcosis in a Chinese tertiary hospital. BMC Pulm Med. 23, 277 (2023).

Iyer, K. R., Revie, N. M., Fu, C., Robbins, N. & Cowen, L. E. Treatment strategies for Cryptococcal infection: challenges, advances and future outlook. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19 (7), 454–466 (2021).

Cao, W., Jian, C., Zhang, H. & Xu, S. Comparison of clinical features and prognostic factors of Cryptococcal meningitis caused by Cryptococcus neoformans in patients with and without pulmonary nodules. Mycopathologia 184, 73–80 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. Clinical analysis of 16 cases of pulmonary cryptococcosis in patients with normal immune function. Ann. Palliat. Med. 9, 1117–1124 (2020).

Lu, Y. et al. Clinical characteristics and image features of pulmonary cryptococcosis: a retrospective analysis of 50 cases in a Chinese hospital. BMC Pulm Med. 22, 137 (2022).

Yamamura, D. & Xu, J. Update on pulmonary cryptococcosis. Mycopathologia 186 (5), 717–728 (2021).

Perfect, J. R. et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of Cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50 (3), 291–322 (2010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L.Z. and L.L. conducted clinical research and manuscript preparation. L.L. and Y.L.Z. conducted data collection and interpretation of results. W.L. and C.R. conducted imaging analysis. W.L. conducted the design and supervision of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Yl., Liu, L., Li, W. et al. Clinical-imaging diversity of exudative pulmonary cryptococcosis with different immune states. Sci Rep 15, 25346 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10807-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10807-3