Abstract

Alzheimer disease (AD) is characterized by the deposition of amyloid fibrils, such as senile plaques, composed of amyloid β peptide (Aβ). As a novel therapeutic modality, we have previously developed an azobenzene–boron complex type photocatalyst that photo-oxygenates Aβ fibrils. And the in vivo photo-oxygenation reaction using this photocatalyst successfully reduced the Aβ fibrils in the brain. Since Aβ fibril is one of the causative molecules in the brains of AD patients, the photocatalyst is expected to be a new modality for disease-modifying therapy against AD. However, the exact relationship between light energy and photo-oxygenating activity for Aβ fibrils remains unclear. In this paper, we have demonstrated using mass spectrometric analysis that the number of oxygens added to Aβ fibrils was increased in a sigmoidal curve with the logarithm of light energy. We also showed that it depended on the total light energy, not on the irradiance. These data suggest that photo-oxygenation proceeds at even lower levels of light energy, and it may be possible to induce photo-oxygenation in areas where light penetration is difficult, such as the human brain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia, which is pathologically characterized by the accumulation of amyloid fibrils composed of amyloid β peptide (Aβ)1,2. Aβ is converted from a soluble state into insoluble amyloid fibrils with a cross-β sheet structure, contributing to neuronal dysfunction3. There are several Aβ species, such as Aβ42 and Aβ40, and especially Aβ42 is more aggregation-prone species4,5,6,7.

One of the current disease-modifying therapies for AD is antibody drugs that target the aggregated Aβ. For example, the recently approved lecanemab is an anti-Aβ antibody8 that binds to aggregated Aβ in the brain and promotes clearance by microglial cells, leading to amelioration of pathology and attenuation of the disease progression9,10. These excellent clinical results with antibody drugs strongly suggest the importance of clearance of aggregated Aβ from the brain in AD patients. However, antibody drugs still have several problems, not only the high development costs, but also low permeability across the blood–brain barrier (BBB) due to their large molecular weight11. Therefore, alternative strategies to enhance amyloid clearance are still needed.

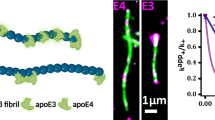

We have developed the photo-oxygenation technology that can selectively oxygenate Aβ aggregates using a small compound, photocatalyst. The photocatalyst is designed to be activated only when it binds to the Aβ aggregates and is irradiated with light, resulting in the generation of singlet oxygen and oxygenation of the surrounding aggregates12,13,14. In addition, we have also developed the photocatalyst with improved BBB permeability based on the structure of azobenzene–boron complex, and successfully demonstrated the non-invasive in vivo photo-oxygenation in the brain of living AD model mice by intravenous administration of this catalyst and light irradiation from outside the skull without any surgery13. This catalyst can selectively oxygenate the 6His, 13His, 14His, and 35Met residues in Aβ aggregates, rather than Aβ monomers13. And importantly, we have shown that in vivo photo-oxygenation can reduce the amount of aggregated Aβ in the brain due to the enhanced Aβ clearance by microglia13,14. Furthermore, we confirmed that photo-oxygenation of Aβ suppressed cytotoxicity against primary neurons13. These results suggest that photo-oxygenation is comparable to antibody therapy and has potential as a novel therapeutic strategy against AD. However, although the photocatalyst is activated by light irradiation, the detailed relationship between the Aβ photo-oxygenation and light energy remains unclear. In this paper, we focused on the BBB-permeable photocatalyst developed based on azobenzene–boron complex, and investigated the photo-oxygenation activity for Aβ fibrils depending on the light energy at 610 nm. We found that photo-oxygenation was increased in a sigmoidal curve with the logarithm of light energy, not linearly, suggesting that photo-oxygenation proceeds at even lower levels of light energy, and it may be possible to induce photo-oxygenation in areas where light penetration is difficult, such as the human brain.

Materials and methods

Design of the irradiation device

The irradiation device with the stirring stage showed a high uniformity of light energy delivered to the photocatalyst in the sample. The irradiation device consists of the arrayed orange LEDs with wavelength of 610 nm (Nippon Chemical Industrial Co., Ltd.) and the light guide with an aluminum mirror for uniform irradiance, which is covered with black plastic on the outside (Fig. 1A). For the stirring stage, a transparent non-slip acrylic plate was placed under the dish (IWAKI) at a distance of 1 cm on a rubber attachment of a vortex mixer. The irradiation device was positioned with a clamp to cover the dish on the stirring stage. The sample was stirred using the vortex mixer, and air was supplied from the side using a fan (Fig. 1B).

The light irradiation device used in this study. (A) Photograph of the light irradiation device. (B) Schematic diagram of the light irradiation device. (C) Spectral irradiance distribution of the device. (D) Irradiation uniformity of the device. The irradiance was measured at the nine representative points at 100 mW/cm2. The irradiance was 98.4 ± 1.26 mW/cm2, and the irradiation uniformity was 96.2%.

Measurement of irradiance and uniformity

The irradiance and spectrum at the irradiated surface were measured using a spectroradiometer USR-45DA (Ushio Inc.). The peak wavelength, full width at half maximum, and irradiance were determined from the spectral irradiance distribution. The irradiance uniformity was evaluated as the ratio between the highest and lowest irradiance on a grid of measuring points located ± 15 mm from the center of the irradiated surface.

Measurement of specimen temperature

The temperature of the sample during irradiation was measured using a thermal viewer (Teledyne FLIR LLC). The thermographic images were taken from the side of the device. The temperature was estimated from the image.

Preparation of Aβ fibrils

Amyloid β isopeptide (Aβ42, Peptide Research Institute Co., Ltd.) was dissolved in 0.1% TFA (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC) to a concentration of 200 μM and stored at − 80 °C. The stock solution was diluted with 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4 (disodium hydrogen phosphate and sodium dihydrogen phosphate; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) to a final concentration of 20 μM for Aβ42 isopeptide. Under neutral conditions, Aβ42 is generated by an O-to-N intramolecular acyl transfer reaction. The solution was then incubated at 37 °C for 3 h to yield the Aβ42 fibril.

Photo-oxygenation of Aβ fibrils

The azobenzene–boron complex type photocatalyst13 was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) to a concentration of 1 mM and stored at − 80 °C. The stock solution was added to the Aβ42 fibril solution to final concentrations of 5 μM (= 25 mol%) to 20 μM (= 100 mol%). 100 μL of the solution was transferred to a dish for irradiation. After irradiation (100 mW/cm2 for 3 s to 1000 s), the sample was collected from the dish and mass spectrometric analysis was performed. Note that the sample was handled in a light-shielded container after the addition of the photocatalyst. Since previous study has confirmed that photo-oxygenation is selective for Aβ aggregates rather than monomers, Aβ42 monomers were not used as a control in this study13.

Calculation of the average number of photo-oxygenations for Aβ fibrils

After the photo-oxygenation, Aβ42 fibrils were extracted and desalted using a C18 resin-packed pipette tip (Merck Life Science). The sample/matrix mixture was crystallized on a MALDI plate using α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA, Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd.), and used as the sample for MALDI-TOF MS (SHIMADZU CORPORATION).

Mass spectra were obtained to calculate the number of photo-oxygenations for Aβ42 fibrils. For each oxygen adduct peak in the mass spectra, the number of photo-oxygenations was assigned based on the molecular weight. The ratio of each oxygen adduct was then calculated from the ratio of signal intensities. Finally, the average number of photo-oxygenations was calculated as the sum of all products of each ratio and the number of oxygen adducts, which is the representative value of photo-oxygenation.

Fitting model and calculation of ED50

In this study, we used the following formula as the reaction model, which represents the relationship between the photo-oxygenation number (y) and the irradiation energy (x):

where a is the saturation value of the photo-oxygenation number, and b is the value inversely proportional to the effective dose. By substituting half of the saturation value of the photo-oxygenation number in Eq. 1, the ED50 can be derived as follows:

The derivation of Eq. 1 is shown below.

Assuming that the rate of photo-oxygenation by the catalyst is proportional to the concentration of non-photo-oxygenating sites remaining on Aβ fibrils, the rate of photo-oxygenation is expressed using the initial concentration of non-photo-oxygenating sites [Non]init, the concentration of photo-oxygenated sites [Oxygenated], and the rate constant k as follows:

Solving this equation gives:

Since the irradiation energy (x) is proportional to the irradiation time (t), and the number of photo-oxygenations (y) is proportional to the concentration of photo-oxygenated sites [Oxygenated], the relationship between y and x can be expressed as follows:

Equation 1 was fitted to the experimental data using the least squares method to obtain the saturation value (a) and the ED50.

Statistical analysis

In Figs. 2, 3, and 4, multiple experiments were performed, and the mean and the standard deviation were calculated. The values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. In the figures, the observed values are represented by circles, the mean values are represented by lines, and the standard deviations are represented by error bars.

Photocatalyst concentration dependence of the photo-oxygenation. (A) Mass spectrometric spectrum of photo-oxygenated Aβ42. Photo-oxygenation was performed using the indicated molar ratio of the photocatalyst (0–100%) and 30 J/cm2 of irradiation energy (100 mW/cm2 for 300 s). The measurements were performed three times, and the spectra were summed. (B) The average number of photo-oxygenations calculated from (A). The circles represent the individual experiments. mean ± SD.

Light energy dependence of the photo-oxygenation. Light energy dependence of the average number of photo-oxygenations using a concentration of 100 mol% photocatalyst and the indicated light energy (100 mW/cm2 for 3–1000 s). Measurements were performed three times, and the circles represent the individual experiments (mean ± SD). The dashed line represents the fitted curve of Eq. 1.

Irradiance dependence of the photo-oxygenation. The irradiation dependence of the average number of photo-oxygenations using a concentration of 100 mol% photocatalyst and the 3 J/cm2 of light energy (the indicated irradiance for 30–1000 s). Measurements were performed three times, and the circles represent the individual experiments (mean ± SD). The correlation coefficient between irradiance and the oxygenation number was 0.21, and the slope of the linear approximation was 0.00065.

Results

Development of the light irradiation device

To evaluate the exact relationship between photo-oxygenation activity and light energy, we first developed the light irradiation device (Fig. 1A,B). The spectral irradiance distribution of this device showed a wavelength at 610 nm with a full width at half maximum of 86 nm (Fig. 1C). The irradiance was measured at the nine representative points at 100 mW/cm2. As shown in Fig. 1D, the irradiance was 98.4 ± 1.26 mW/cm2, and the irradiation uniformity, expressed as the ratio of the maximum to minimum values, was 96.2%. The irradiance variation at 30 s intervals during 18 min of continuous irradiation was 0.26%, and the peak wavelength shift was 0.024 nm. In addition, irradiation for 10 min increased the temperature by less than 2 °C. These data suggested that this device could provide stable and uniform light to the sample, with negligible instability in irradiance and peak wavelength, as long as the irradiation was below 100 mW/cm2 for less than 18 min. The experiments in this study were then carried out within this range.

Aβ photo-oxygenation depending on photocatalyst concentration and light energy

We evaluated the photo-oxygenation activity for Aβ42 fibrils using mass spectrometry analysis. Although the native Aβ42 peak was indicated as molecular weight of 4512, we observed the additional peaks of Aβ42 shifted by 14–81 molecular weights when we photo-oxygenated using irradiation at 30 J/cm2 and different concentrations of the photocatalyst in the range of 25% to 100% in molar ratio (Fig. 2A). In addition, the average number of oxygen atoms added to Aβ42, which was calculated from the signal intensity, showed a linear correlation between photo-oxygenation and catalyst concentration (Fig. 2B, the correlation coefficient is 0.984), indicating the photocatalyst concentration-dependent photo-oxygenation activity.

To next investigate the relationship between photo-oxygenation activity and light energy, we photo-oxygenated Aβ42 fibrils using 100% concentration in molar ratio of the photocatalyst and different light energy from 0.3 to 100 J/cm2 with the developed device. We observed that the average number of oxygenations was increased in a sigmoidal manner, not linearly (Fig. 3). The ED50, the half-maximal effective light energy, was estimated to be 6.05 ± 1.02 J/cm2.

Irradiance (W/cm2) is expressed as light energy (J/cm2) per second. We then examined the photo-oxygenation activity when we set the light energy to 3 J/cm2 with different irradiance and time. We found that the photo-oxygenation activity was not changed by irradiance (Fig. 4), suggesting that it depends on the total light energy, not on the irradiance specific to the device.

Discussion

Irradiation is an important factor to achieve sufficient therapeutic effects of photo-oxygenation. In this paper, we have clearly shown that the photo-oxygenation activity for Aβ fibrils depends on the light energy in a sigmoidal manner, based on the cooperative reaction mechanism. Considering the catalytic cycle and the reaction mechanism of the photocatalyst shown in the previous study13, photo-oxygenation by the photocatalyst is considered to proceed through the following five steps. The first step is the binding of the photocatalyst to the Aβ fibrils; the second is the excitation of the bound photocatalyst by photon absorption; the third is the intersystem crossing of the excited photocatalyst to the triplet state; the fourth is the energy transfer to oxygen, generating singlet oxygen; and the fifth step is the reaction of singlet oxygen with the Aβ fibril. All steps could be involved in the light energy dependency of photo-oxygenation.

We previously reported that the Kd value of this photocatalyst for aggregated Aβ is 3.4 μM13. Considering that, when Aβ concentration is 20 μM, the formation of Aβ-catalyst complex in the step 1 of the photo-oxygenation process is predicted to increase approximately linearly with catalyst concentration up to 100 mol%, and approach a plateau above 100 mol%. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 2, we revealed a linear relationship between photo-oxygenation activity and photocatalyst concentration within the range of 0–100 mol%. These indicate that photo-oxygenation activity could depend on the concentration of the bound photocatalyst, and that photocatalyst concentrations up to 100 mol% may be suitable for efficient photo-oxygenation.

On the other hand, we also revealed the sigmoidal relationship between light energy and photo-oxygenation. The photo-oxygenation is considered a cooperative reaction which proceeds in multiple steps. In addition, as shown in Fig. 3, our result matched Eq. 1, which assumes in the fifth step that the rate of photo-oxygenation depends on the concentration of the non-photo-oxygenating sites. These cooperative reactions involving these multiple steps and factors could explain the sigmoidal relationship between light energy and oxygenation. Furthermore, as shown in Eq. 2, we could estimate the ED50 from our result, which represents the light energy when photo-oxygenation is 50%. It has been previously reported using Monte Carlo simulations of light penetration into the brain that approximately 10% of the incident near-infrared light at 660–980 nm reached the grey matter15. Although further investigations are still needed, this suggests that 60 J/cm2 of light energy from the body surface would be sufficient to deliver the 6 J/cm2 light energy of ED50 for photo-oxygenation using this photocatalyst in the brain.

It is thought that photo-oxygenation eventually depends on the total amount of excited photocatalysts in step 2–3 of reaction process. And it is also expected that the total amount of excited photocatalysts depends on the total number of photons given by irradiation. Therefore, Fig. 4 shows that photo-oxygenation proceeds depending on the total light energy, not on irradiance. In other words, the photo-oxygenation could occur equally at either 100 mW/cm2 of irradiance for 20 min or 10 mW/cm2 of irradiance for 200 min. Additionally, even if extremely high irradiance is supplied, the amount of the excited photocatalyst is likely to be saturated and unable to absorb additional energy. We can choose the light device with appropriate irradiance and the irradiation time based on reaction mechanisms to avoid negative effects such as burns due to high temperature induced by higher irradiance.

In this paper, we successfully showed how much light energy is needed to induce photo-oxygenation activity in in vitro analysis. However, we still need to consider how to deliver this amount of light energy to the proper brain regions in humans. In this paper, we revealed that photo-oxygenation was increased in a sigmoidal curve with the logarithm of light energy, not linearly. This suggests that photo-oxygenation proceeds at even lower levels of light energy, and it may be possible to induce photo-oxygenation in areas where light penetration is difficult, such as the human brain. However, the light energy is lost through absorption by many biological factors, such as skull, blood, and brain tissues. Additionally, it is also known that Aβ deposition spreads from the cortex to the limbic system including the hippocampus and basal ganglia, and finally to the hypothalamus, brainstem, and cerebellum, as the AD stage progresses. This suggests that we need to consider different irradiation methods and devices depending on the stage of AD, because the distance between the light irradiation device and the target areas is different. Further examination will be needed to develop the light irradiation device for clinical use of photo-oxygenation.

Conclusion

In this study, we successfully revealed the pharmacodynamic response of the light energy, as an important parameter for Aβ photo-oxygenation using the BBB-permeable photocatalyst developed based on azobenzene–boron complex. Our findings will enable to develop the light irradiation method to achieve sufficient therapeutic effects of photo-oxygenation for Aβ fibrils in vivo towards clinical use.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 7(2), e105–e125 (2019).

Daviglus, M. L. et al. National Institutes of Health state-of-the-science conference statement: Preventing Alzheimer disease and cognitive decline. Ann. Intern. Med. 153(3), 176–181 (2010).

Tycko, R. Amyloid polymorphism: Structural basis and neurobiological relevance. Neuron 86(3), 632–645 (2015).

Selkoe, D. J. Alzheimer’s disease: Genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol. Rev. 81(2), 741–766 (2001).

Kang, J. et al. The precursor of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid A4 protein resembles a cell-surface receptor. Nature 325(6106), 733–736 (1987).

Iwatsubo, T. et al. Visualization of A beta 42(43) and A beta 40 in senile plaques with end-specific A beta monoclonals: Evidence that an initially deposited species is A beta 42(43). Neuron 13(1), 45–53 (1994).

Jarrett, J. T., Berger, E. P. & Lansbury, P. T. Jr. The carboxy terminus of the beta amyloid protein is critical for the seeding of amyloid formation: Implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochemistry 32(18), 4693–4697 (1993).

Söderberg, L. et al. Lecanemab, aducanumab, and gantenerumab: Binding profiles to different forms of amyloid-beta might explain efficacy and side effects in clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics 20(1), 195–206 (2023).

Wang, W. et al. Immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 44(10), 807–814 (2012).

van Dyck, C. H. et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 388(1), 9–21 (2023).

Pardridge, W. M. Treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and blood–brain barrier drug delivery. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 13(11), 394 (2020).

Ni, J. et al. Near-infrared photoactivatable oxygenation catalysts of amyloid peptide. Chem 4(4), 807–820 (2018).

Nagashima, N. et al. Catalytic photooxygenation degrades brain Aβ in vivo. Sci. Adv. 7(13), eabc9750 (2021).

Ozawa, S. et al. Photo-oxygenation by a biocompatible catalyst reduces amyloid-β levels in Alzheimer’s disease mice. Brain 144(6), 1884–1897 (2021).

Li, T., Xue, C., Wang, P., Li, Y. & Lanhui, Wu. Photon penetration depth in human brain for light stimulation and treatment: A realistic Monte Carlo simulation study. J. Innov. Opt. Health Sci. 10(5), 1743002 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Shinichi Torii (Vermilion Therapeutics Inc.), Yuki Yamanashi, Hiroki Umeda, Ryota Matsukawa (Laboratory of Synthetic Organic Chemistry, Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, The University of Tokyo) for useful discussions, and Tomohiko Kio, Hiroshi Shibata (Ushio Inc.) for technical assistance.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (JP18K06653 to Y.H.), a Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research (JP19K22484 to Y.S.), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (JP23H02622 to Y.H. and JP24K02153 to Y.S.), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) (JP19H01015, JP23H00394 to T.T.), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) (JP23H05466 to M.K.), Grant-in-Aid for Transformative Research Areas (B) (JP23H05036 to Y.H.), Grant-in-Aid for Transformative Research Areas (A) (JP24H01787 to Y.S.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), grants from Innovative Research Group by the Strategic International Brain Science Research Promotion Program (Brain/MINDS Beyond) (JP19dm0307030 to Y.H.), AMED-PRIME (JP23gm6410017 to Y.H.), Brain Mapping by Integrated Neurotechnologies for Disease Studies (Brain/MINDS) (JP22dm0207072 to T.T.), Research and Development Grants for Dementia (21dk0207046, 23dk0207061 and 24dk0207073 to T.T.) and Strategic International Collaborative Research Program (SICORP) (JP19jm0210058 to Y.S.) from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), a Joint research funds with USHIO Inc..

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YK and MKu performed experiments. YK and YH wrote the draft and revised it. YS, MKa and TT were involved in discussing, drafting, and editing the manuscript. All authors approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

YK is a full-time employee of USHIO Inc. The other authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kawai, Y., Kuriyama, M., Sohma, Y. et al. The dynamics of oxygenation to Aβ fibrils using an azobenzene–boron complex type photocatalyst and light energy. Sci Rep 15, 25241 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10880-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10880-8