Abstract

Dose verification in preclinical CyberKnife-based stereotactic radiosurgery (CK-SRS) of intracranial tumors is complicated by the unique characteristics of the system, including its highly conformal, non-coplanar radiation delivery and small-field irradiation. This raises concerns about the reliability of dosimetric measurements in CK-SRS radiobiological studies, emphasizing the need for standardized dosimetry protocols to improve dose accuracy and reproducibility. This study aims to evaluate a fully 3D-printed mouse phantom as a tool for preclinical intracranial CK-SRS dose verification. A 3D-printed mouse phantom was fabricated using clear resin and glass-filled polyamide (PA3200 GF) for tissue-bone-equivalent structures and modified to accommodate both EBT3 film and thermoluminescent dosimeters (TLD). Two treatment configurations were employed using CyberKnife M6 system, including two simple static field plans and two complex non-planar plans. The dosimetric evaluation of the mouse phantom involved comparing the mean dose and dose discrepancies between film profile measurements, TLD-derived point-dose readings, and the corresponding doses calculated by the treatment plan system (TPS) for each configuration. Across all measurements for single-beam and non-planer stereotactic treatment configuration, dose values exhibited a deviation of no more than 4.20% from the corresponding TPS calculated data. The 2D dose distributions obtained from the film measurements and those calculated by the TPS were successfully registered. The mean dose differences for lateral profiles showed a high level of agreement, with discrepancies of only 2.23%. Similarly, the agreement was similarly excellent with a mean dose difference of 2.31% along the anteroposterior axes. TLD measurements also displayed comparable agreement with TPS-calculated results, with the maximum dose difference recorded at 2.20% for the single-beam and 4.12% for the non-planar treatment configuration. This study demonstrates the utility of 3D-printed mouse phantom for accurate dose assessment in preclinical intracranial CK-SRS. The phantom serves as an effective tool for pre-treatment dose verification, improving dosimetric precision while offering a cost-efficient solution for radiobiological research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

CyberKnife-based stereotactic radiosurgery (CK-SRS) delivers high-dose radiation from multiple dynamically adaptive angles, enabling submillimeter precision in the treatment of intracranial tumors1,2. As a high-dose, lower fraction modality, CK-SRS emerges as a promising alternative to conventional fractionated radiotherapy while serving as an effective adjunct to surgical interventions3,4. Despite the expanding clinical practices of single-fraction and hypo-fractionated protocols, robust empirically substantiated radiobiological investigations into the intracranial application of high-dose radiation therapies remain insufficient. To elucidate the radiobiology effects of CK-SRS on intracranial pathologies, developing a dependable in vivo model is essential. Preclinical animal models can mimic the tumor microenvironment, especially when SRS is applied to mouse models under radiation conditions similar to those in humans5,6,7,8.

Dose verification in preclinical radiotherapy is crucial to ensure the precision, consistency, and reproducibility of both treatments and their biological outcomes. However, accurate dosimetry in small-animal studies is challenging due to the small field sizes and steep dose gradients commonly encountered in treatment systems such as CK-SRS. To address this, the creation of anatomically realistic small-animal phantoms has become an important approach to improve the consistency of pre-treatment dose verification in preclinical radiotherapy9. The fabrication of anatomically accurate small-animal phantoms plays a pivotal role in enhancing the consistency and reliability of pre-treatment dose verification in preclinical radiotherapy. Unlike traditional models, which typically featured simplistic geometries such as cylindrical shapes or unrealistic anatomical representations10,11,12, the advancement of 3D printing technology has enabled the reliable construction of more realistic and heterogeneous phantoms13,14,15. Multi-material 3D printing, in particular, offers significant advantages by allowing the integration of anatomical variations, facilitating the creation of precise phantom models16,17,18. Optimizing 3D printing materials for radiological properties remains challenging12. Nevertheless, anatomically precise small-animal phantoms significantly enhance preclinical dose measurement reliability by preserving realistic anatomy.

Currently, only five studies have explored the use of dedicated SRS linear accelerators for mouse irradiation: two employing Gamma Knife19,20 and three with CyberKnife5,7,11. While CK-SRS has been applied to mouse brain tumors, dose validation was limited to basic checks using a standard cylindrical phantom, without a comprehensive assessment of dose accuracy11. In contrast, this study provides dose verification under CK-SRS using an anatomically accurate 3D-printed mouse phantom. The phantom was adapted to incorporate EBT3 radiochromic film within the mouse brain and a TLD for dose measurement. This approach aims to enhance the precision of CK-SRS preclinical dosimetry, improves dose measurement consistency across small-animal radiotherapy research institutions and further supports the development of a reliable in vivo model to study the radiobiological effects of CK-SRS on intracranial pathologies in mouse models.

Methods and materials

3D printed mouse phantom fabrication

The mouse phantom geometry used in this study is based on the design described in Price’s work16. The phantom was sectioned along the central coronal plane to allow for placement of Gafchromic EBT3 film (Gafchromic, Bridgewater, NJ), with 1-mm cavities for TLD (Ruifute Radiation Measurement Instrument Co., Ltd, Beijng) insertion (as shown in Fig. 1a). The phantom was constructed from clear resin and glass-filled polyamide (PA3200 GF), both sourced from Qile Industrial Co., Ltd, Dongguan. The clear resin served as a tissue-equivalent material for simulating the CyberKnife beam’s interaction with soft tissue, while PA3200 GF, a higher-density material, was selected for the bone-equivalent structure, enabling on-board visualization and accurate localization of anatomical targets (Fig. 1b,c). Details of the additive manufacturing process are summarized in Table 1.

(a) Photographic images of the 3D-printed mouse phantom, with EBT3 film and TLD sites outlined (1 mm active element in red, not to scale) are outlined. The scanned phantom in (b) coronal and (c) sagittal axes. (d) The mouse phantom was scanned at 120 kVp in a simulation CT, with the coarsest resolution in the longitudinal axis being 0.628 mm. Position of fiducial markers attached to the body restraint apparatus in (e) X-ray B image plate and (f) X-ray A image plate.

Phantom irradiations

As illustrated in Fig. 1d, CT simulation was performed using a restraint apparatus that maintained accurate and repeatable positioning of mouse phantoms during imaging and treatment procedures. Considering the technical impracticality of intracranial marker insertion in murine models, the stereotactic coordinate system was established using five external fiducial markers integrated with the restraint apparatus, as diagrammatically represented in Fig. 1e,f.

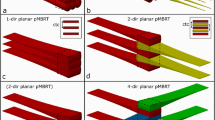

A total of two treatment configurations were applied, including simple static field plans and complex non-planar plans, with irradiations involving both EBT3 film and the TLD positioned in the axial plane. Given the small target volume in the mouse phantom, the fixed cone collimators were employed throughout this study. In the first configuration, the simple static field was delivered to the phantom using 7.5 mm and 5 mm collimators. The schematic diagram of single incident radiation beam is shown in Fig. 2a,b. In the second phase, two distinct non-planar treatment plans were designed for the phantom irradiation. A dose of 2.5 Gy (prescribed 2 Gy at 80% isodose line) was planned for a point near the center of the target volume using the CyberKnife treatment planning system, with 5 mm and 7.5 mm collimators. The first non-planar treatment plan consisted of 26 beams: 15 with 5 mm collimators and 11 with 7.5 mm collimators. The second non-planar plan involved 23 beams: 14 with 5 mm collimators and 9 with 7.5 mm collimators. The incident radiation beam configurations are shown in Fig. 2c,d. Treatment plan was designed with Cyberknife M6 system (Accuray Precision Version 3.3.1.3, CNNC Accuray) following the manual delineation of an 8 mm spherical target volume on the simulation CT scans of the phantoms. The contralateral brain was outlined as organ at risk (OAR) to define a radiation-sparing region. The second non-planar plan aimed to spare the contralateral brain from radiation, while the other did not prioritize this sparing. Each treatment plan was executed and delivered three times to obtain repeat measurements.

Dose measurements and analysis

Film measurements were considered as the gold standard for assessing the 2D dose distribution in the axial plane at the target volume. To maintain consistent positioning across CK-SRS irradiations, only one-half of the phantom was secured to the treatment couch, allowing for film insertion or replacement without the need to remove the entire phantom. The EBT3 films were scanned within 12 h post-irradiation using an Epson Expression 12000XL scanner (Seiko Epson, Shiojiri, Nagano) configured in professional mode, with settings for positive film type, transparency mode, and no color correction. The scans were performed at a resolution of 300 dpi. The red channel was selected for dose analysis due to its greater sensitivity to dose variation compared to the green or blue channels21. The dosimetric registration and analysis between TPS calculated dose and film measured dose were performed with FilmQA Pro Version 5.0 software (Ashland Inc., Wilmington, Delaware, USA, https://www.filmqapro.com/). Alignment was performed using Automated feature-based registration module in this software. The built-in algorithm identified common high-gradient features in both film dose images and TPS reference images, then computed an optimal rigid transformation to maximize mutual information. While a sensitometry curve was employed to convert the optical density of EBT3 films into dose values, using the films as absolute dosimeters presented considerable challenges. Therefore, TLDs were employed for precise absolute dose measurements. The TLDs used in this study had dimensions of 1 mm × 1 mm × 0.9 mm. To ensure accurate readings, each TLD underwent individual calibration following the procedure outlined in the AAPM TG 19122. As the ionization chamber represents the gold standard in clinical dosimetry, validating TLD doses against its measurements is essential. However, the phantom design restricts the incorporation of cavities sized for standard ionization chambers. To rigorously address this point and establish a reference standard for the delivered dose, we performed additional Plan Quality Assurance (Plan QA) procedures using both a calibrated ionization chamber (Exradin A16, collector diameter: 0.3 mm) and TLDs in a solid water phantom. The relevant details were provided in Supplemental Material and the results of plan QA, obtained using TLDs and ionization chamber measurements were comparatively analyzed in Table S1.

Results

The dosimetric evaluation of the mouse phantom was conducted by analyzing the mean dose and dose discrepancies between 2D film profile measurements and TLD-derived point-dose readings for each treatment configuration. Across all measurements, dose values exhibited a deviation of no more than 3% from the corresponding TPS data, with detailed results presented in the following sections.

Film dosimetry

Figure 2 presents the TPS calculated and experimentally measured dose distributions obtained from film measurements. Each registered distribution pair demonstrates strong visual concordance, particularly in the central dose regions of the target volume. Dose profiles along the anteroposterior and lateral axes were analyzed for both single-beam and non-planar stereotactic treatment plans, with comparative results illustrated in Figs. 3 and 4, respectively. The film dosimetry curves were created based on the inverse intensity projected on the EBT3 films (as shown in Supplemental Material Figure S1). Unlike the methodology described by Biglin et al.13, we did not generate dose calibration curves for the batch of EBT3 film used in our research. All film comparisons in this study were performed exclusively in relative mode, with no dependence on absolute position or absolute dose.

X-direction dose profiles from TPS and film measurement for (a) 7.5 mm and (e) 5 mm single-beam, along with the corresponding Y-direction profiles for (b) 7.5 mm and (f) 5 mm. The solid blue line represents the TPS-calculated dose distribution, while the red dots indicate the measured film data. Panels (c,d, g,h) illustrate the discrepancies between the TPS-fitted curve and the film measurements data.

The measured dose distributions exhibited strong agreement with the TPS calculated, with deviations along lateral axes remaining within 1.58% for single-beam irradiation and 2.28% for non-planar stereotactic plans. Similarly, deviations along the anteroposterior axes were 1.96% and 2.09% for single-beam and non-planar stereotactic plans, respectively. However, localized discrepancies were observed, reaching a maximum of ± 3.77% and ± 6% for single-beam and stereotactic configurations along lateral axes. In the anteroposterior direction, the highest discrepancies recorded were ± 5.65% and ± 5.20%, respectively. The mean absolute differences along lateral axes between the full TPS-calculated and measured film dose profiles were quantified as 1.60% for the 7.5 mm single-beam, 1.56% for the 5 mm single-beam, 2.23% for the first stereotactic plan and 2.26% for the second stereotactic plan. Regarding the anteroposterior axes, the mean absolute differences were 1.62%, 2.31%, 2.15%, and 2.03%, respectively.

TLD dosimetry

Table 2 provides a comparative analysis of TLD-based dose measurements and TPS-calculated results, along with their corresponding percentage deviations. The percentage difference was determined using the formula: 100% × (TPS-TLD)/TPSmax. For each treatment configuration, the dose difference was found to be less than 4.2%, with absolute maximum and minimum deviations of 2.20% and 1.34% for the 7.5 mm and 5 mm single-beam setups, respectively. Regarding non-planar plans, deviations of 3.57% and 4.12% were observed.

Discussion

The reliability of radiobiological studies focused on dose–response relationships is fundamentally dependent on the precision of dosimetry and the robustness of quality assurance protocols implemented beforehand. A cost-effective 3D-printed mouse phantom was developed as a practical solution for dosimetric assessments in CK-SRS for intracranial radiobiological studies. To ensure the accuracy and consistency of the measurements, dose verification was carried out using both radiochromic EBT3 film and TLD, with the results compared against the dose calculations obtained from the TPS. Realistic small-animal phantoms are essential in preclinical trials, as they enhance dose precision and, consequently, improve treatment outcomes, particularly in complex irradiation configurations. The steep dose gradients encountered with the Cyberknife system result in heightened sensitivity of the dose distribution to the body contours of small-animal models. This sensitivity diminishes the effectiveness of simplified phantom geometries. In contrast, 3D-printed models offer the advantage of accurately replicating intricate anatomical features.

Overall, a strong correlation was observed between the measured and calculated dose distributions shown in Fig. 2. As depicted in Fig. 3, dose distribution profiles in the high-dose regions exhibited excellent agreement, with the mean deviation consistently remaining below 3% in all case. However, more pronounced discrepancies were noted at the edges of the sampled penumbra, though these differences remained under 6% across the entire region. Such deviations may have stemmed from misalignment or rotation of the film relative to the idealized TPS data, or from interpolation errors within regions characterized by steep dose gradients during the registration process. TLD measurements displayed similar agreement with TPS-calculated results, with the maximum dose difference recorded at 4.13% for the non-planar treatment configuration. Despite the high resolution provided by 3D printing, which allowed the physical mouse phantom to closely mirror the digital STL model, the skeletal heterogeneities were not designed to accurately reflect the dosimetric characteristics of real bone. For more realistic dose measurements, it would be advantageous to incorporate materials with higher mass density and effective atomic number to better simulate the attenuation properties of bone. This modification would allow the phantom to more accurately represent the dose distribution in biological tissue, particularly in situations like intracranial irradiation, where bone attenuation significantly affects dose delivery. The uncertainty in absolute dose measurements for TLDs arises from several inherent limitations. Scaling down phantoms for small-animal irradiation introduces significant deviations in scatter conditions. This is critical even when TLDs measure in the soft tissue region of phantom but are positioned adjacent to PA3200 GF bone-equivalent materials. The proximity may violate lateral electronic equilibrium and cause non-negligible errors in detector response23. Meanwhile, sub-millimeter positional errors become the dominant error source because minor displacements significantly alter the dose sampling point24. Additionally, as shown in the far-right column of Table 2, the difference of TLD point-dose measurements in non-coplanar plans is higher than in single-beam plans. This finding is consistent with the research of Guimaraes et al., which demonstrated that the angular response of TLDs exhibits significant variations beyond 60° incidence, primarily attributed to self-shielding25.

The absence of standardized dosimetry in small animal preclinical radiation research is a significant barrier to the clinical translation of novel therapies. Seed et al. conducted a dosimetric comparison among seven laboratories in Japan and the USA, employing different radiation sources, including orthovoltage X-ray machines and 137Cs or 60Co irradiators26. Their findings revealed considerable errors in dose delivery, primarily attributable to the lack of standardized dosimetry and quality assurance protocols. In some cases, discrepancies of up to 22% were observed between the target and delivered doses. Similarly, Patallo et al. developed a comprehensive dosimetry testing framework to address these issues27. The framework utilized zoomorphic mouse phantoms and alanine dosimeters, validated through Monte Carlo simulations, and was implemented across five institutions using Xstrahl’s small animal irradiation platforms. The study revealed discrepancies between calculated and measured doses, with one institution showing a dose difference exceeding 12% due to erroneous input data. Both studies underscore the urgent need for the establishment of standardized dosimetry procedures and independent verification methods, which are essential for improving dose accuracy and ensuring reproducibility in preclinical radiation research. Building upon these findings, our future work will focus on conducting a similar study specifically within the CK-SRS platform across multiple institutions, utilizing a standardized experimental setup and precise dosimetric characterization. Given unique ability of CK to deliver highly conformal, non-coplanar radiation with submillimeter accuracy, we aim to further investigate its dose distribution characteristics in small animal models. This study will enable us to refine CK-SRS preclinical dosimetry methods, minimize uncertainties in dose delivery, and enhance the reproducibility of radiation experiments, ultimately improving the translational potential of CK-SRS preclinical radiobiological research. Meanwhile, the selection of a prescription dose of 2.5 Gy for this study requires specific discussion, as it falls below typical therapeutic doses used in SRS. It is essential to emphasize that our primary objective was to validate targeting accuracy and dosimetric performance, not to assess therapeutic efficacy. To achieve this, we chose a 2.5 Gy dose level, which provided a robust signal-to-noise ratio for film dosimetry and TLD measurements. This dose enabled us to obtain reliable dosimetric data, allowing precise evaluation of targeting accuracy and dose distribution. Future studies will focus on replicating these validation procedures using clinically relevant SRS doses to bridge this gap and optimize our techniques for small animal preclinical radiation research.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the utility of 3D-printed mouse phantom for accurate dose assessment in preclinical intracranial CK-SRS. The dosimetric evaluation of the mouse phantom was carried out by employing film for dose profile measurements and TLD for point-dose assessments. For all measurements across the single-beam and non-planar stereotactic treatment configurations, dose values deviated by no more than 4.2% from the corresponding TPS-calculated data. Our results illustrated that the mouse phantom is an effective tool for pre-treatment dose verification, improving dosimetric precision while providing a cost-efficient solution for radiobiological research.

Data availability

The data underlying the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Kuo, J. S., Yu, C., Petrovich, Z. & Apuzzo, M. L. The CyberKnife stereotactic radiosurgery system: Description, installation, and an initial evaluation of use and functionality. Neurosurgery 62, 785–789 (2008).

Chang, S. D., Main, W., Martin, D. P., Gibbs, I. C. & Heilbrun, M. P. An analysis of the accuracy of the CyberKnife: A robotic frameless stereotactic radiosurgical system. Neurosurgery 52(1), 140–147 (2003).

Acker, G. et al. Image-Guided robotic radiosurgery for treatment of recurrent grade II and III meningiomas. A single-center study. World Neurosurg. 131, e96–e107 (2019).

Soliman, H., Das, S., Larson, D. A. & Sahgal, A. Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) in the modern management of patients with brain metastases. Oncotarget 7(11), 12318 (2016).

Jelgersma, C. et al. Establishment and validation of cyberknife irradiation in a syngeneic glioblastoma mouse model. Cancers 13(14), 3416 (2021).

Ko, E., Forsythe, K., Buckstein, M., Kao, J. & Rosenstein, B. Radiobiological rationale and clinical implications of hypofractionated radiation therapy. Cancer/Radiothérapie 15(3), 221–229 (2011).

Kiljan, M. et al. CyberKnife radiation therapy as a platform for translational mouse studies. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 97(9), 1261–1269 (2021).

Wu, C.-C. et al. Quality assessment of stereotactic radiosurgery of a melanoma brain metastases model using a mouselike phantom and the small animal radiation research platform. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 99(1), 191–201 (2017).

Welch, D., Turner, L., Speiser, M., Randers-Pehrson, G. & Brenner, D. J. Scattered dose calculations and measurements in a life-like mouse phantom. Radiat. Res. 187(4), 433–442 (2017).

Miller, B. W. et al. 3D printing in X-ray and Gamma-Ray Imaging: A novel method for fabricating high-density imaging apertures. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 659(1), 262–268 (2011).

Kim, H. et al. Establishing a process of irradiating small animal brain using a CyberKnife and a microCT scanner. Med. Phys. 41(2), 021715 (2014).

Filippou, V. & Tsoumpas, C. Recent advances on the development of phantoms using 3D printing for imaging with CT, MRI, PET, SPECT, and ultrasound. Med. Phys. 45(9), e740–e760 (2018).

Biglin, E. R. et al. A preclinical radiotherapy dosimetry audit using a realistic 3D printed murine phantom. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 6826 (2022).

Esplen, N., Alyaqoub, E. & Bazalova-Carter, M. Technical Note: Manufacturing of a realistic mouse phantom for dosimetry of radiobiology experiments. Med. Phys. 46(2), 1030–1036 (2019).

Perks, J. R., Lucero, S., Monjazeb, A. M. & Li, J. J. Anthropomorphic phantoms for confirmation of linear accelerator-based small animal irradiation. Cureus 7(3), e254 (2015).

Price, G. et al. An open source heterogeneous 3D printed mouse phantom utilising a novel bone representative thermoplastic. Phys. Med. Biol. 65(10), 10NT02 (2020).

Wegner, M., Frenzel, T., Krause, D. & Gargioni, E. Development and characterization of modular mouse phantoms for end-to-end testing and training in radiobiology experiments. Phys. Med. Biol. 68(8), 085009 (2023).

Lascaud, J. et al. Fabrication and characterization of a multimodal 3D printed mouse phantom for ionoacoustic quality assurance in image-guided pre-clinical proton radiation research. Phys. Med. Biol. 67(20), 205001 (2022).

Perez-Torres, C. J. et al. Toward distinguishing recurrent tumor from radiation necrosis: DWI and MTC in a gamma knife–irradiated mouse glioma model. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 90(2), 446–453 (2014).

Jiang, X. et al. A gamma-knife-enabled mouse model of cerebral single-hemisphere delayed radiation necrosis. PLoS ONE 10(10), e0139596 (2015).

Liu, K., Jorge, P. G., Tailor, R., Moeckli, R. & Schüler, E. Comprehensive evaluation and new recommendations in the use of Gafchromic EBT3 film. Med. Phys. 50(11), 7252–7262 (2023).

Kry, S. F. et al. AAPM TG 191: Clinical use of luminescent dosimeters: TLDs and OSLDs. Med. Phys. 47(2), e19–e51 (2020).

Papanikolaou, N., Battista, J. J., Boyer, A. L. et al. Tissue inhomogeneity corrections for megavoltage photon beams (2004).

Das, I. J., Ding, G. X. & Ahnesjö, A. Small fields: nonequilibrium radiation dosimetry. Med. Phys. 35(1), 206–215 (2008).

Guimaraes, C., Moralles, M. & Okuno, E. GEANT4 simulation of the angular dependence of TLD-based monitor response. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 580(1), 514–517 (2007).

Seed, T. M. et al. An interlaboratory comparison of dosimetry for a multi-institutional radiobiological research project: Observations, problems, solutions and lessons learned. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 92(2), 59–70 (2016).

Patallo, I. S. et al. Development and implementation of an end-to-end test for absolute dose verification of small animal preclinical irradiation research platforms. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 107(3), 587–596 (2020).

Funding

This study was supported by the Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan of Shanghai Science and Technology Commission [Grant Nos. 24692107302 and 24692121500].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XL, XA, and LQ designed, implemented the study and wrote the manuscript. HJ modified mouse phantom, MS optimized treatment plans, GM and XD revised the manuscript and supervised the study.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Ai, X., Qiu, L. et al. Preclinical dose assessment of cyberknife with small animal intracranial irradiation using a 3D printed mouse phantom. Sci Rep 15, 27534 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10962-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10962-7