Abstract

Accurate information on urban tree species composition is critical for urban green space ecosystem management. However, achieving large-scale, high-precision species identification in complex metropolitan environments remains challenging. This study assessed the potential of medium-resolution multi-temporal optical imagery combined with airborne LiDAR for tree species classification in large heterogeneous urban areas (> 5000 km²). The results indicate that precise large-scale identification of urban tree species distribution is feasible by integrating multi-seasonal Sentinel-2 imagery with airborne LiDAR data based on a Random Forest hierarchical classification model. The overall classification accuracies for deciduous broadleaf species and evergreen broadleaf species were 63.32% and 76.77%, respectively. Multi-temporal spectra were the primary explanatory variables, with spring bands significantly affecting the classification of deciduous broadleaf species. For evergreen broadleaf species, each season has its own dominant spectral information. Classifications combining data from three seasons outperformed single- or two-season combinations. The incorporation of LiDAR-derived metrics improved the classification results for most species, with accuracy increases of up to 18.75% point for deciduous broadleaf species. Overall, the results demonstrate the effectiveness of combining medium-resolution multi-temporal optical imagery with LiDAR data for urban tree species classification, laying a foundation for quantifying ecosystem services provided by urban trees through remote sensing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urban trees play a crucial role in providing ecosystem services, including purifying the air, alleviating heat in cities, and improving the health and quality of life for humans1,2,3. Effective planning and allocation of urban trees is a nature-based solution for maximizing their benefits and contributing to sustainable urban development4,5. Timely and accurate identification of urban tree species composition and distribution is a crucial prerequisite for the planning and management of urban trees.

Accurately obtaining spatial information on urban tree distribution in highly heterogeneous and complex urban environments presents significant challenges. Ground surveys are the most accurate method for collecting urban tree species distribution data. However, this approach is often costly and only suitable for small-scale studies. Integrating ground surveys with remote sensing data is a promising approach for mapping urban tree species6. Compared to ground surveys, remote sensing technology provides observational data at various scales, enabling large-scale, high-precision, and automated classification of urban tree species7,8. Remote sensing-based species identification has been extensively studied in natural environments9,10,11. However, urban environments present additional challenges such as the complexity of land use, diversity of urban tree composition, fragmented spatial layout, and various human-induced pruning and management activities. Some recent studies have already begun attempts in this direction. For example, six tree species were classified in the Grajaú neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, using a fusion of digital aerial imagery and LiDAR data12. In the Greater Chicago Area, 18 common tree species were classified using dense, multi-temporal, high-resolution optical imagery, achieving an overall classification accuracy of 60%13. In the Brussels-Capital Region, the five most common tree species were classified by integrating multi-temporal PlanetScope data with ultra-high-resolution aerial imagery, yielding an OA of 88%14. A decrease in classification accuracy was observed as the number of species categories increased13,14,15. Seven urban tree species within a 100 km² area of Tampa, Florida, were identified by combining multi-season high-resolution Pléiades imagery with airborne LiDAR data16. These studies highlight that optical imagery and LiDAR are the two primary data sources for urban tree species classification.

Optical imagery captures the biophysical characteristics of urban tree species, and its spectral, temporal, and spatial resolutions play critical roles in the accurate identification of urban tree species. Spectral differences among species reflect variations in leaf morphology and biochemical factors17. The visible band (VIS, 0.4–0.7 μm) captures differences in the absorption of various plant pigments; the near-infrared radiation spectrum (NIR, 0.7–1.3 μm) reflects differences in internal cell structures of plants; and the shortwave infrared spectrum (SWIR, 1.3–2.5 μm) indicates variations in water content and other biochemical components of vegetation18. Previous studies have identified specific bands important for the classification of urban tree species. For example, the blue light band was identified as significant in the classification of conifer species19. In terms of temporal resolution, different tree species exhibit varying patterns of bud burst, leaf unfolding, and flowering throughout the year, which enhance the separability of tree species based on optical imagery captured at different times20,21,22. Imagery captured during the autumn senescence period provided the most valuable phenological information for tree species classification in Washington, D.C., using multi-temporal WorldView-3 imagery23. In terms of spatial resolution, it is generally believed that higher spatial resolution leads to improved accuracy in tree species classification24,25. However, there generally exists an inverse relationship between the spatial and temporal resolutions of remote sensing imagery, necessitating a comprehensive trade-off analysis for optimal application26,27. It was found that among the optical imagery with 4 m, 8 m, and 30 m spatial resolutions, the best tree species classification results were achieved with an 8 m pixel size28.

LiDAR data can capture the biophysical characteristics of urban tree species and serve as an effective complement to optical imagery29,30,31. LiDAR sensors emit thousands of laser pulses and record the time delay between pulse emission and return, creating a 3D point cloud of the imaged area. From the point-cloud data, various tree structure-related features can be derived, such as canopy height, crown width and shape, and leaf area index32. Many studies have investigated the benefits of combining optical imagery with LiDAR point-cloud data for identifying tree species and their compositions. For instance, combining LiDAR data with hyperspectral imagery notably improved the accuracy of identifying urban tree species33. Additionally, fusing optical and LiDAR data increased the average F1-score for classifying urban tree species in tropical regions by 12.6% compared to using optical bands alone12. However, other studies have shown that including LiDAR point-cloud data is not always beneficial. For example, canopy height information had little impact on classification accuracy28. Canopy height information may even cause confusion rather than improve species discrimination34. The reasons behind these phenomena or under which circumstances and for which tree species LiDAR data can effectively improve the classification accuracy, remain unclear. Therefore, additional studies are needed to investigate the potential of combining optical and LiDAR data for the classification of tree species and to assess the added value of the latter in improving tree species identification.

Another important but often overlooked factor is cost-effectiveness34. In urban environments, unmanned aerial systems (UAS) have become a primary source of high-resolution imagery and LiDAR data with excellent temporal flexibility35. However, acquiring both ultra-high-resolution imagery and LiDAR data can be costly, and there are numerous restricted flight zones within urban areas. Therefore, many studies have focused on the classification and identification of tree species at the local scale within urban areas36,37,38. These studies aim to maximize the classification accuracy within a single site; however, their value is limited because the results are often not generalizable to other areas. For large-scale applications, the most competitive sensor systems are satellite-based, including medium and high spatial resolution systems (Landsat, Sentinel-2, and Rapid Eye)39. Therefore, exploring classification approaches for urban tree species based on satellite data, supplemented by airborne data, for the entire urban area holds significant research value and practical implications for creating large-scale, high-precision, and intelligent urban tree species identification.

The Sentinel-2 satellites offer a notable improvement in freely accessible multi-spectral remote sensing data, offering improved spatial and temporal resolutions. It is currently the satellite data with the highest spectral resolution among all freely available datasets with long-term time-series observation capabilities40. A 5-day revisit cycle and 10-m spatial resolution have been demonstrated to improve forest species mapping in natural environments41,42,43,44. However, their applicability in identifying urban tree species in highly heterogeneous metropolitan environments remains unclear.

Shanghai is one of the largest cities in China and benefits from a subtropical monsoon climate, unique geographical location, and diverse ecological environments, which provide favorable conditions for vegetation growth. However, human activities, such as urban expansion, transportation infrastructure development, and other industrial activities, have resulted in a complex internal vegetation structure and composition, presenting challenges for tree species identification and ecological research. This study uses Shanghai as a case study to explore how combining multi-season Sentinel imagery with airborne LiDAR data can enhance the mapping of dominant tree species and their distribution in highly heterogeneous urban spaces. Specifically, the following research questions are addressed:

(1) Can the 10-m resolution Sentinel-2 temporal data effectively identify tree species on a large scale within urban areas?

(2) Does using structural metrics from airborne LiDAR enhance tree species classification?

Data and methods

Study area

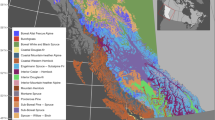

The study area is mainland Shanghai (Fig. 1), covering the main urban area of Shanghai and surrounding terrestrial areas, excluding water bodies and Chongming Island. This region spans approximately 5,439 km2. This region experiences a humid subtropical climate characterized by four distinct seasons, annual precipitation of approximately 1,200 mm, and an average annual temperature of approximately 17.7 °C. These conditions provide a favorable environment for plant growth. The urban forests in the study area exhibit rich biodiversity and remarkable ecological functions. Remote sensing data indicates a tree cover of 26%, with a wide variety of species, including mainly native tree species, such as Cinnamomum camphora, Ginkgo biloba, Magnolia denudata, and Ulmus pumila, and exotic tree species, such as Koelreuteria paniculata, Platanus acerifolia, and Prunus serrulata.

Field operations & data collection

A two-month field survey was conducted by the research team in the summer of 2023, during which a total of 7,493 tree species sample records were collected. The approach involved selecting 18 major green spaces, evenly spread across the area (Fig. 1). Locations of tree distributions and species information were recorded, excluding uncommon tree species with fewer than 100 samples. Finally, 19 dominant tree species were identified (Table 1). The sample size of these dominant tree species accounted for 90.86% of the total measured samples.

Remote sensing basic data and the determined experimental schemes

Spectral imagery and LiDAR data for urban tree species features

Urban tree species exhibit high heterogeneity due to their location in urban areas. The selection of appropriate vegetation features directly influences the quality of classification results, making it a crucial step in the process of classifying dominant tree species in urban environments. It is not sufficient to rely on field surveys alone to capture the features of urban trees on a large scale, and remote sensing data provide the basis for the acquisition of a large number of samples used to train and validate models in the process of intelligent identification of urban tree species. In this study, Sentinel-2 multispectral imagery fused with airborne LiDAR data was used to classify urban tree species based on basic data from field surveys. The Sentinel-2 data are obtained from the European Space Agency data-sharing website (https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/) and pre-processed using SNAP and ENVI software for resampling, band synthesis, mosaicing, cropping, cloud masking and missing value filling. Airborne LiDAR data were collected during the summer of 2021 using a Feima D200 unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) platform (Feima Robotics Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) equipped with a RIEGL miniVUX-1UAV LiDAR scanner (RIEGL Laser Measurement Systems GmbH, Horn, Austria). Data were acquired at an altitude of 100 m above the ground over seven parks within the study area, with an average point density of 52 points/m². The LiDAR scanner was operated at a pulse repetition frequency of 100 kHz and a maximum scanning rate of 100 scans per second. The flight was conducted under clear windless conditions at a constant speed of 10 m/s.

Base feature set construction

Features across spectral, temporal, and physical multiple dimensions were selected after comprehensive consideration of interspecies variations to construct the base feature set for tree species classification (Table 2).

Spectral features characterize the distribution of reflectance/radiation intensity across different wavelengths, comprising: (1) spectral bands directly extracted from preprocessed Sentinel-2 data, and (2) spectral indices derived from band combinations to enhance feature discrimination. The spectral bands correspond to 10 bands (visible, red-edge, near-infrared, and short-wave infrared) in Sentinel-2 imagery. Based on established vegetation and tree species identification studies45,46,47 24 widely adopted spectral indices were selected as the spectral indices feature set.

Temporal features attempt to capture the differences in phenological changes of different trees through multi-seasonal imagery and computation of different seasonal band combinations. Corresponding to the three growth stages of tree leaves, Sentinel-2 images were acquired for the three seasons of spring (May), summer (August) and autumn (October) of 2023 covering the study area (Table 3). Based on the extraction of 30 Sentinel-2 image bands for the three seasons, the seasonal trajectory difference index was calculated with the following formula16:

where \(\:i\) denotes the \(\:i\)-th band. Thus, the 12 bands corresponding to Sentinel-2 A yielded a total of 10 STDIs.

Physical features primarily characterize the vertical structure of trees. Based on LiDAR data collected from urban tree species in the study area park using the VUX-1UAV LiDAR scanner, LIDAR360 software (GreenValley International, California, USA) was used for preprocessing the LiDAR data. Subsequently, three canopy structure parameters—CH, CC, and LAI—were extracted from the preprocessed point cloud data. The specific calculation method is as follows: First, the watershed segmentation algorithm is applied to the denoised and filtered LiDAR point cloud data for individual tree segmentation, obtaining parameters such as tree positions and canopy height. Canopy closure represents the proportion of the vertical projection of the forest canopy over the land area. In this study, within a 10 m×10 m statistical unit, the ratio of first-return vegetation points to the total first-return points is calculated. The leaf area index is the total leaf area per unit ground area and is an important parameter for characterizing the vegetation canopy structure. The study uses an algorithm that, within a 10 m×10 m statistical unit, constructs a 3D grid with 1.5 times the average point spacing of the point cloud, based on the average point spacing of the point cloud. The number of 3D grids in each layer and the number of grids containing LiDAR points are then counted. By calculating the frequency of LiDAR points in each layer and multiplying by a leaf inclination correction factor, the leaf area index for each layer is obtained. Finally, all layers’ leaf area index values are summed to obtain the total leaf area index for the entire statistical unit. Finally, combined with remote sensing data inversion algorithms, the CH, CC, and LAI—three LiDAR-derived features—were generated for the entire study area, with a spatial resolution of 10 m.

Experimental schemes design

Based on the spectral, temporal, and physical features described above, seven experimental schemes were designed to determine the optimal feature combination for urban dominant tree species classification, with the goal of improving classification accuracy in the study area. Scheme 1 constructed a classification model using single-season spectral features (spring, summer, and autumn), each containing 10 spectral bands and 24 spectral indices. Scheme 2 employed temporal features, including all 30 spectral bands from three seasons (10 bands × 3 seasons) and 10 seasonal trajectory difference indices. Scheme 3 focused on physical features, utilizing three LiDAR-derived metrics: CH, CC, and LAI. Subsequent schemes examined pairwise combinations: Scheme 4 combined spectral and temporal features (112 features), Scheme 5 combined temporal and physical features (43 features), and Scheme 6 combined spectral and physical features (105 features). Scheme 7 integrated all features, employing spectral, temporal, and physical features (115 features) for tree species identification modeling.

Feature selection

The constructed base feature set contains a large number of features. To avoid issues such as insignificant features, multicollinearity, and feature redundancy, feature selection is necessary to identify the optimal feature subset for each experimental scheme. Considering the characteristics of the features, classification objectives, and data distribution properties in this study, the Kruskal-Wallis48 method was employed for feature significance testing, removing features with p > 0.05. Subsequently, multicollinearity analysis was performed on the remaining features. Pearson correlation coefficient matrix (|r|>0.8) and variance inflation factor (VIF > 10) were used to identify redundant features. Finally, combined with random forest feature importance evaluation, features with higher contributions to tree species classification (top 20% in importance) were prioritized for retention.

The mapping framework of urban tree species distribution and hierarchical classification model construction

The study employed a Random Forest algorithm to construct a multi-level classification system for mapping urban tree species distribution across metropolitan areas, achieving stepwise species identification (Fig. 2). In constructing the Random Forest classification model, the bagging method is first used to sample the original training set from the previous step, creating multiple training subsets. A base classifier is then trained for each subset. Finally, a voting method is used to combine the predictions of all base classifiers, and the class with the most votes is selected as the model’s final output. For accuracy validation, 20% of the total tree samples from field surveys were used as validation samples. Four accuracy evaluation metrics—Overall Accuracy (OA), F1-score, Producer Accuracy (PA), and User Accuracy (UA)—were employed to assess the classification accuracy. The specific methodology for urban tree species identification using the multi-level Random Forest classification model is as follows:

-

Level 1: Using 10 bands from single-season Sentinel-2 imagery to classify land use and land cover in the study area, the terrestrial area of Shanghai was categorized into five land types: forest, grassland, cropland, impervious surface, and waterbody.

-

Level 2: Within the forest areas identified in Level 1, three-season Sentinel-2 imagery (totaling 30 bands) was further employed to distinguish between evergreen broadleaf forest, evergreen coniferous forest, deciduous broadleaf forest, and deciduous coniferous forest.

-

Level 3: By comparing the classification performance of seven experimental schemes, the optimal classification scheme was determined to further identify specific urban tree species within each forest type.

Results

Urban tree species classification status from multiple schemes

The classification accuracies of the seven experimental schemes were compared to determine the optimal classification scheme for different forest type species. For evergreen coniferous forests and deciduous coniferous forests, their main species consist solely of Pinus massoniana and Metasequoia glyptostroboides, requiring no further classification. Therefore, the focus here is primarily on identifying dominant species within deciduous broadleaf forests (DBF) and evergreen broadleaf forests (EBF). Figure 3a,b respectively illustrate the feature selection processes corresponding to the seven experimental schemes for DBF and EBF species.

Based on the feature subsets selected for each experimental scheme, dominant species identification was conducted for both DBF and EBF, with the classification accuracies shown in Table 4. The results demonstrate significant differences in classification performance between DBF and EBF. For DBF species classification, Scheme 7 (Spectral + Temporal + Physical) achieved the highest accuracy among all schemes (OA: 63.32%, F1-score: 0.63), showing a 29.65% point improvement in OA over the lowest-performing Scheme 3 (OA: 33.67%, F1-score: 0.34). Classification schemes combining multiple feature dimensions (Schemes 4–7) generally outperformed those using single-dimensional features (Schemes 1–3). For EBF species, Scheme 5 (Temporal + Physical) yielded the highest classification accuracy (OA: 76.77%, F1-score: 0.75). The two-dimensional feature combination schemes (Schemes 4–6) performed comparably to the three-dimensional combination (Scheme 7), with all achieving OA values above 75%. Based on these findings, Scheme 7 and Scheme 5 were selected for subsequent analysis of DBF and EBF species, respectively.

Mapping the distribution of urban dominant tree species

The resulting 2023 distribution of dominant tree species across Shanghai’s mainland area at 10 m resolution is shown in Fig. 4. In addition, four areas with high tree densities were randomly and uniformly selected for detailed inspection (Fig. 4, areas A, B, C, and D). These areas were zoomed in and compared with high-definition Google Map images for visual analysis. The obtained tree distribution maps demonstrated a high degree of consistency in spatial distribution with the Google Earth images.

The most widely distributed species in the study area are Cinnamomum camphora, Metasequoia glyptostroboides, and Salix babylonica, which together account for 57.56% of the total urban forest area in the study region. Cinnamomum camphora, a native species of Shanghai, holds an important role in the city’s greening efforts. Metasequoia glyptostroboides and Salix babylonica are predominantly found in areas with abundant water sources, such as riverbanks and lake shores. Other major tree species in Shanghai include Zelkova serrata, Ginkgo biloba, Sapindus mukorossi, Osmanthus fragrans, Prunus serrulata, Koelreuteria paniculata, Platanus acerifolia, and Ligustrum lucidum, collectively occupying 37.82% of the forested area in the study region. The distribution ranges of Acer rubrum, Magnolia denudata, Liquidambar formosana, Populus alba, Prunus cerasifera, Triadica sebifera, Phyllostachys edulis, and Pinus massoniana are relatively limited, covering less than 5% of the total forest area in the study region.

Classification accuracy of urban dominant tree species across forest types

The multi-layer classification model achieved overall accuracies of 89.36% for five land-use types and 72.89% for four forest-type classes, respectively. For the third-layer species-level classification, the accuracy of dominant tree species in DBF and EBF was further evaluated based on the optimal feature selection scheme. The results revealed significant differences in classification accuracy across different forest types. Table 5 presents the confusion matrix for the classification of DBF tree species, with an OA of 63.32% and a F1-score of 0.63. The PA ranged from 55.38% for Zelkova serrata (ZESE80) to 80.95% for Populus alba (POAL7). The highest PA was observed for Populus alba (POAL7) with a PA of over 80%, followed by Magnolia denudata (MADE7) and Ginkgo biloba (GIBI2), with PAs of 79.17% and 75.44%, respectively. The UA showed a broader range, with the highest UA being 75.47% for Salix babylonica (SABA) and 72.92% for Platanus acerifolia (PLAC). In addition, Magnolia denudata (MADE7) and Prunus serrulata (PRSE3) exhibited UAs that exceeded 70%. In contrast, the UAs for Triadica sebifera (TRSE6) and Acer rubrum (ACRU) were below 50%. Table 6 presents the classification results for four EBF tree species, with an OA of 76.77% and a F1-score of 0.75, indicating relatively good classification performance. The highest UA was observed for Cinnamomum camphora (CICA) at 95.07%, with a PA of 77.59%, representing the highest classification accuracy. The classification accuracies for Osmanthus fragrans (OSFR2) and Ligustrum lucidum (LILU2) were relatively high, with PAs of 77.27% and 70%, respectively, and UAs exceeding 60%. In contrast, Phyllostachys edulis (PHED4) showed a UA of only 19.05%, despite a PA of 80.00%, reflecting poor classification performance.

Relative importance of predictors

To better understand the contribution of selected spectral, temporal, and physical features to the predictive performance of the tree species classification models for different forest types, the feature importance of the Random Forest classification models for DBF species and EBF species was calculated using the Mean Decrease Accuracy method (Fig. 5). For DBF species, the spectral band information in spring exhibits higher importance compared to summer and autumn, with key bands such as Band 3 (green) and Band 8 (near-infrared) in spring imagery. The importance of spectral bands across seasons follows a declining trend from spring to summer and further to autumn. Additionally, spectral indices play seasonally distinct roles: among spring indices, the MNDWI shows the highest importance, followed by the NDGI. In summer and autumn, the CRI and NDII are the most critical indices. Among LiDAR-derived physical metrics, CH demonstrates significantly greater importance than CC and LAI, highlighting its role as a key structural feature for identifying DBF species. In the classification of EBF species, dominant spectral information varies across seasons. For instance, the Band 8 (near-infrared) and Band 11 (shortwave infrared) show high importance in spring, while the Band 6 (near-infrared) and Band 2 (blue) serve as key spectral features in summer and autumn respectively. The STDI indices in bands 2 and 8, which incorporate multi-seasonal phenological information, also showed high importance. In addition, CH also played a significant role in the classification of broadleaf evergreen species, but it did not differ much from the performance of the other two structural features.

Discussion

Significance of observing time series data

Trees exhibit phenological changes, which vary across different species. Therefore, using multi-season imagery is generally more likely to improve the accuracy of urban tree species identification than using single-season images21,49,50. To deepen our insight into phenology-related spectral variations, the classification accuracy of DBF and EBF species was assessed by constructing classification models using features from different seasons and season combinations. (Fig. 6). It was observed that summer imagery is crucial for the classification of both DBF and EBF species, as its classification accuracy was higher than that of spring or autumn imagery alone. However, this is not a universal rule, as there is no consensus in the literature regarding the optimal season for tree classification21,51. This variation may be attributed to differences in geographic location, climate, and tree species selected for classification across different studies. For instance, in the study of 32 tree species in Luoyang, China, Liu et al.20 found that the tree flowering and leafing period (spring) was the optimal period for species identification, while Yang et al.52 found that the highest classification accuracy was achieved when using mid-summer imagery for tree species classification in the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence region of Central Ontario, Canada. Additionally, Fang et al.23 reported that autumn was the most important season for classifying 19 tree species in Washington, D.C.

However, the classification accuracy remained relatively low when using data from a single season, such as spring, summer, or autumn, highlighting the limitations of using single-temporal data for species classification. The combination of two or three seasons significantly improved the classification accuracy of tree species. As shown in Fig. 6, when spectral features from two different seasons are combined, the summer-autumn combination exhibits better classification performance for DBF species compared to other seasonal combinations. For EBF species, the spring-summer combined features achieve higher classification accuracy. The model incorporating spectral features from all three seasons—spring, summer, and autumn—achieved the highest classification accuracy for both DBF and EBF species. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies10,20,53 further emphasizing the importance of multi-temporal data in tree species classification. Therefore, it is recommended that greater emphasis be placed on the significance of time-series data in tree species classification in future research, particularly by considering local climatic characteristics and focusing on key phenological stages of different species across various regions, to fully explore the potential of time-series imagery for urban tree species classification.

Effectiveness of optical–LiDAR fusion

Although the Sentinel-2 time-series data used in this study provided valuable spectral information for urban tree classification, LiDAR data further complemented these datasets by offering physical information such as tree structure and shape. Previous studies have shown that the fusion of data from different sources typically yields better results for species classification54. As shown in Fig. 7, the addition of LiDAR data increased the classification accuracy for most DBF species. For example, the PA of Triadica sebifera (TRSE6) increased by 18.75% points, Koelreuteria paniculate (KOPA) by 8.02% points, Sapindus mukorossi (SAMU6) by 6.15% points, Platanus acerifolia (PLAC) by 5.4% points, and Populus alba (POAL7) by 4.54% points. In terms of UA, Platanus acerifolia (PLAC) showed an improvement of 14.59% points, Koelreuteria paniculata (KOPA) by 9.68% points, Zelkova serrata (ZESE80) by 7.14% points, and Prunus serrulata (PRSE3) by 4.54% points. However, a small number of species exhibited minor decreases in classification accuracy, including Prunus cerasifera (PRCE2), Magnolia denudata (MADE7), and Ginkgo biloba (GIBI2). As typical small ornamental trees in Shanghai’s urban landscape, these species are often intentionally planted interspersed with other varieties to enhance visual appeal, resulting in crown mixing and partial occlusion with adjacent trees. Extracting accurate LiDAR structural information from such complex planting configurations proves challenging34,55 ultimately compromising classification accuracy.

In contrast, for EBF species, the inclusion of LiDAR data only marginally increased the classification accuracy. The PAs and UAs of Ligustrum lucidum (LILU2) increased by 7.68 and 5.88% points respectively, while the improvements for Cinnamomum camphora (CICA) and Osmanthus fragrans (OSFR2) in both PAs and UAs were less than 3% points each. The classification accuracy of Phyllostachys edulis (PHED4) remained at the original level. Overall, the integration of LiDAR data effectively enhanced the classification accuracy for specific tree species. This finding is consistent with that of other studies on urban tree species identifying, highlighting the effectiveness of fusing optical and LiDAR data in improving the accuracy of urban tree classification.

Additionally, it is noteworthy that among the tree species studied, four pairs of species belong to the same family (i.e., Samanea saman (SAMU6) and Koelreuteria paniculata (KOPA), Prunus serrulata (PRSE3) and Prunus cerasifera (PRCE2), Salix babylonica (SABA) and Populus alba (POAL7), as well as Osmanthus fragrans (OSFR2) and Ligustrum lucidum (LILU2)). After incorporating LiDAR-derived features, the classification accuracy for Koelreuteria paniculata (KOPA), Samanea saman (SAMU6), Prunus serrulata (PRSE3), and Ligustrum lucidum (LILU2) significantly improved. This suggests that when tree species within the same family exhibit similar spectral characteristics, the integration of LiDAR data can effectively enhance the classification accuracy for DBF species.

Limitations and prospects

Accurately identifying urban tree species remains a challenging task. In this study, the effectiveness of combining multi-seasonal Sentinel-2 time-series imagery with limited LiDAR data was demonstrated for identifying dominant urban tree species, with overall accuracies of 63.32% and 76.77% achieved for DBF species and EBF species, respectively. It should be noted that the classification accuracy for DBF was found to be moderate (13.45% lower than EBF), which may be attributed to two factors: (1) the fine canopy structures of deciduous trees (e.g., leaf distribution, branch morphology) were not sufficiently captured by the 10-m resolution imagery, and (2) the DBF category was composed of a greater variety of tree species with an imbalanced sample distribution. While due to variations in tree species classifications and differences in the spatial, spectral, and temporal resolutions of the data, a direct comparison with previous research is not possible53,56. Nevertheless, the findings of this study demonstrate that the integration of 10-m resolution multi-temporal multispectral imagery (Sentinel-2) with limited airborne LiDAR data can be employed as a cost-effective approach for urban tree species distribution identification, particularly offering a scalable solution for large-scale urban tree species monitoring.

To improve the accuracy of tree species classification, future research should focus on two directions. First, incorporating dense time-series data should be considered. Our findings demonstrate the importance of multi-temporal optical imagery in classifying urban tree species. However, this study used imagery from only three seasonal time points (spring, summer, and autumn), which limited the ability to capture the full spectrum of phenological variations in each species. For diverse urban trees, acquiring more frequent time-series images during periods of high phenological variability between species may significantly enhance classification results. Second, increasing the use of ground-based LiDAR data should be explored. Our study utilized data captured from an overhead perspective, which is widely used for the classification and mapping of tree species distributions on non-public lands53. However, this approach limits the accuracy of understory tree classification. As in this study, small landscape species such as Phyllostachys edulis (PHED4), Prunus cerasifera (PRCE2), etc., are often shaded by the canopy of nearby tall trees, leading to lower classification accuracy. Ground-based LiDAR data can potentially improve the identification accuracy for such species. However, the spatial coverage of ground-based data is typically limited and integrating data from different perspectives presents a significant challenge.

Conclusion

This study investigated the potential of medium-resolution, multi-temporal, multi-spectral Sentinel-2 optical imagery combined with limited airborne LiDAR data for large-scale identifying of common urban tree species in highly heterogeneous urban environments. Using multi-spectral bands/indices from Sentinel-2 captured during spring, summer, and autumn, STDIs for each band, and LiDAR-derived CH, CC, and LAI metrics as independent variables, along with field survey data as dependent variables, a hierarchical classification approach with a random forest classifier was applied to classify common tree species. The key findings are summarized below:

-

The identification of dominant tree species distribution across large urban areas using multi-seasonal Sentinel-2 imagery combined with airborne LiDAR data has proven feasible. For DBF species, the Spectral + Temporal + Physical combination achieved the highest classification accuracy (OA: 63.32%, F1-score: 0.63), while the Temporal + Physical combination was identified as the optimal classification scheme for EBF species (OA: 76.77%, F1-score: 0.75).

-

The spring spectral bands were significantly more important for classifying deciduous broadleaf tree species than those from summer and autumn. For evergreen broadleaf tree species, wavelength information was more important than the timing of image acquisition. Different seasons exhibit distinct dominant spectral information (spring: shortwave infrared and near-infrared bands; summer: near-infrared band; autumn: blue band). Furthermore, the significance of temporal data was confirmed, as using features from multi-seasonal image combinations yielded significantly better results for tree species classification than using features from single- or two-season combinations.

-

Although spectral information is important for classifying tree species, its utility is limited. The integration of LiDAR data effectively improved the classification results. This improvement was less pronounced for evergreen broadleaf tree species, but significantly enhanced the classification accuracy for deciduous broadleaf tree species, with improvements of up to 18.75% point. Notably, when tree species within the same family exhibit similar spectral characteristics, the integration of LiDAR data can effectively improve classification accuracy.

In summary, this study presents a method for classifying common urban tree species in the terrestrial areas of Shanghai by integrating multi-seasonal Sentinel-2 imagery and LiDAR data to build a hierarchical machine-learning classification model. This approach is cost-effective, practical, and transferable, providing a viable solution for large-scale automated mapping of urban tree species distributions. This study offers valuable data support for urban forest management and scientific planning.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yang, Y. et al. How can trees protect Us from air pollution and urban heat? Associations and pathways at the neighborhood scale. Landsc. Urban Plan. 236, 104779 (2023).

Hao, T., Zhao, Q. & Huang, J. Optimization of tree locations to reduce human heat stress in an urban park. Urban Urban Green. 86, 128017 (2023).

O’Brien, L. E., Urbanek, R. E. & Gregory, J. D. Ecological functions and human benefits of urban forests. Urban Urban Green. 75, 127707 (2022).

Tang, L., Shao, G. & Groffman, P. M. Urban trees: how to maximize their benefits for humans and the environment. Nature 626, 261 (2024).

Wang, C., Jin, J., Davies, C. & Chen, W. Y. Urban forests as nature-based solutions: A comprehensive overview of the National forest City action in China. Curr. Rep. 10, 119–132 (2024).

Shahtahmassebi, A. R. et al. Remote sensing of urban green spaces: A review. Urban Urban Green. 57, 126946 (2021).

Bai, Y. et al. Comprehensively analyzing optical and polarimetric SAR features for land-use/land-cover classification and urban vegetation extraction in highly-dense urban area. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs Geoinf. 103, 102496 (2021).

Meng, Q. et al. Research progress and prospects of remote sensing classification of urban vegetation. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Agric Life Sci). 50, 190–199 (2024).

Wan, H. et al. Tree species classification of forest stands using multisource remote sensing data. Remote Sens. 13, 144 (2021).

Immitzer, M. et al. Optimal input features for tree species classification in central Europe based on multi-temporal Sentinel-2 data. Remote Sens. 11, 2599 (2019).

Dalponte, M., Ørka, H. O., Gobakken, T., Gianelle, D. & Næsset, E. Tree species classification in boreal forests with hyperspectral data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 51, 2632–2645 (2012).

Ferreira, M. P. et al. Improving urban tree species classification by deep-learning based fusion of digital aerial images and lidar. Urban Urban Green. 94, 128240 (2024).

Neyns, R., Efthymiadis, K., Libin, P. & Canters, F. Fusion of multi-temporal planetscope data and very high-resolution aerial imagery for urban tree species mapping. Urban Urban Green. 99, 128410 (2024).

Liang, X., Chen, J., Gong, W., Puttonen, E. & Wang, Y. Influence of data and methods on high-resolution imagery-based tree species recognition considering phenology: the case of temperate forests. Remote Sens. Environ. 323, 114654 (2025).

Mäyrä, J. et al. Tree species classification from airborne hyperspectral and lidar data using 3D convolutional neural networks. Remote Sens. Environ. 256, 112322 (2021).

Pu, R. & Landry, S. Mapping urban tree species by integrating multi-seasonal high resolution pléiades satellite imagery with airborne lidar data. Urban Urban Green. 53, 126675 (2020).

Gu, H., Singh, A. & Townsend, P. A. Detection of gradients of forest composition in an urban area using imaging spectroscopy. Remote Sens. Environ. 167, 168–180 (2015).

Pu, R. Hyperspectral Remote Sensing: Fundamentals and Practices (CRC Press, 2017).

Pu, R. & Liu, D. Segmented canonical discriminant analysis of in situ hyperspectral data for identifying 13 urban tree species. Int. J. Remote Sens. 32, 2207–2226 (2011).

Liu, H. Classification of urban tree species using multi-features derived from four-season RedEdge-MX data. Comput. Electron. Agric. 194, 106794 (2022).

Pu, R., Landry, S. & Yu, Q. Assessing the potential of multi-seasonal high resolution pléiades satellite imagery for mapping urban tree species. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs Geoinf. 71, 144–158 (2018).

Madonsela, S. et al. Multi-phenology WorldView-2 imagery improves remote sensing of Savannah tree species. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs Geoinf. 58, 65–73 (2017).

Fang, F. et al. Discriminating tree species at different taxonomic levels using multi-temporal WorldView-3 imagery in Washington DC, USA. Remote Sens. Environ. 246, 111811 (2020).

Martins, G. B. et al. Deep learning-based tree species mapping in a highly diverse tropical urban setting. Urban Urban Green. 64, 127241 (2021).

Egli, S. & Höpke, M. CNN-based tree species classification using high resolution RGB image data from automated UAV observations. Remote Sens. 12, 3892 (2020).

Xiao, J. et al. A review of remote sensing image Spatiotemporal fusion: challenges, applications and recent trends. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 32, 101005 (2023).

Shen, H., Meng, X. & Zhang, L. An integrated framework for the spatio–temporal–spectral fusion of remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 54 (12), 7135–7148 (2016).

Ghosh, A., Fassnacht, F. E., Joshi, P. K. & Koch, B. A framework for mapping tree species combining hyperspectral and lidar data: role of selected classifiers and sensor across three Spatial scales. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs Geoinf. 26, 49–63 (2014).

Münzinger, M., Prechtel, N. & Behnisch, M. Mapping the urban forest in detail: from lidar point clouds to 3D tree models. Urban Urban Green. 74, 127637 (2022).

Alonzo, M., McFadden, J. P., Nowak, D. J. & Roberts, D. A. Mapping urban forest structure and function using hyperspectral imagery and lidar data. Urban Urban Green. 17, 135–147 (2016).

Jones, T. G., Coops, N. C. & Sharma, T. Assessing the utility of airborne hyperspectral and lidar data for species distribution mapping in the coastal Pacific northwest, Canada. Remote Sens. Environ. 114, 2841–2852 (2010).

Liu, L., Coops, N. C., Aven, N. W. & Pang, Y. Mapping urban tree species using integrated airborne hyperspectral and lidar remote sensing data. Remote Sens. Environ. 200, 170–182 (2017).

Alonzo, M., Bookhagen, B. & Roberts, D. A. Urban tree species mapping using hyperspectral and lidar data fusion. Remote Sens. Environ. 148, 70–83 (2014).

Fassnacht, F. E. et al. Review of studies on tree species classification from remotely sensed data. Remote Sens. Environ. 186, 64–87 (2016).

Wu, J. et al. Fine classification of urban tree species based on UAV-based RGB imagery and lidar data. Forces 15, 390 (2024).

Gong, Y. et al. Using UAV lidar intensity frequency and hyperspectral features to improve the accuracy of urban tree species classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. (2023).

Li, X. et al. Urban tree species classification using UAV-based multispectral images and lidar point clouds. J. Geovisualization Spat. Anal. 8, 5 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Classification of street tree species using UAV Tilt photogrammetry. Remote Sens. 13, 216 (2021).

Blickensdörfer, L., Oehmichen, K., Pflugmacher, D., Kleinschmit, B. & Hostert, P. National tree species mapping using Sentinel-1/2 time series and German National forest inventory data. Remote Sens. Environ. 304, 114069 (2024).

Drusch, M. et al. Sentinel-2: esa’s optical high-resolution mission for GMES operational services. Remote Sens. Environ. 120, 25–36 (2012).

Kollert, A., Bremer, M., Löw, M. & Rutzinger, M. Exploring the potential of land surface phenology and seasonal cloud free composites of one year of Sentinel-2 imagery for tree species mapping in a mountainous region. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs Geoinf. 94, 102208 (2021).

Axelsson, A., Lindberg, E., Reese, H. & Olsson, H. Tree species classification using Sentinel-2 imagery and bayesian inference. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs Geoinf. 100, 102318 (2021).

Liu, X., Frey, J., Munteanu, C., Still, N. & Koch, B. Mapping tree species diversity in temperate montane forests using Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 imagery and topography data. Remote Sens. Environ. 292, 113576 (2023).

Brandt, J., Ertel, J., Spore, J. & Stolle, F. Wall-to-wall mapping of tree extent in the tropics with Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2. Remote Sens. Environ. 292, 113574 (2023).

Huang, C. et al. Multi-feature classification of optical and SAR remote sensing images for typical tropical plantation species. Scientia Silvae Sinicae. 57, 80–91 (2021).

Bolyn, C., Michez, A., Gaucher, P., Lejeune, P. & Bonnet, S. Forest mapping and species composition using supervised per pixel classification of Sentinel-2 imagery. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 22 (3), (2018).

Xue, J. & Su, B. Significant remote sensing vegetation indices: A review of developments and applications. J. Sens. 2017 1353691 (2017).

Kruskal, W. H. & Wallis, W. A. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 47 (260), 583–621 (1952).

Thapa, B. et al. Application of multi-temporal satellite imagery for urban tree species identification. Urban For. Urban Green 128409 (2024).

Han, W., Zhang, S., Jiao, Q. & Wu, H. Dominant tree species mapping based on multi-temporal CHRIS hyperspectral satellite data. Invent. Plann. 44, 1–6 (2019).

Grybas, H. & Congalton, R. G. A comparison of multi-temporal RGB and multispectral UAS imagery for tree species classification in heterogeneous new Hampshire forests. Remote Sens. 13, 2631 (2021).

Yang, J., He, Y. & Caspersen, J. Individual tree-based species classification for uneven-aged, mixed-deciduous forests using multi-seasonal WorldView-3 images. In IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS) 827–830 (IEEE, 2017).

Neyns, R. & Canters, F. Mapping of urban vegetation with high-resolution remote sensing: A review. Remote Sens. 14, 1031 (2022).

Hartling, S., Sagan, V., Sidike, P., Maimaitijiang, M. & Carron, J. Urban tree species classification using a WorldView-2/3 and lidar data fusion approach and deep learning. Sensors 19, 1284 (2019).

Chi, D., Yan, J., Yu, K., Morsdorf, F. & Somers, B. Planting contexts affect urban tree species classification using airborne hyperspectral and lidar imagery. Landsc. Urban Plan 257 (000). (2025).

Hemmerling, J., Pflugmacher, D. & Hostert, P. Mapping temperate forest tree species using dense Sentinel-2 time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 267, 112743 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China project (grant numbers 51878279 and 51878418). The authors would like to thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yunfang Jiang: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Funding acquisition. Xianghua Li: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Validation, Writing - Review & Editing. Lixian Peng & Chunjing Li: Software, Data Curation, Visualization. Tao Song: Investigation, Resources, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, Y., Li, X., Peng, L. et al. Assessing the potential of multi-seasonal Sentinel-2 satellite imagery combined with airborne LiDAR for urban tree species identification. Sci Rep 15, 25107 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10971-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10971-6