Abstract

3D Concrete Printing (3DCP) offers significant advantages over traditional construction such as faster construction time, reduced material wastage, and enhanced ability to execute complex architectural designs. The incorporation of various fibres and industrial wastes into 3DCP can improve performance and sustainability but introduces non-linear effects on compressive strength (CS) that are difficult to predict with standard laboratory methods. This study aims to develop reliable prediction models for the CS of 3DCP by employing advanced neural network and deep learning algorithms such as Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), and Radial Basis Functional Neural Network (RBFNN). A comprehensive database of 200 experimental instances of CS of 3DCP was collected from published literature. The database includes mixture constituents of 3DCP as inputs and CS as the output. The trained algorithms were validated by means of k-fold validation, error metrics, and residual assessment. Among the tested algorithms, the CNN model exhibited the highest predictive performance with a testing R² value of 0.95, demonstrating its robustness in modelling the complex behaviour of 3DCP. To enhance interpretability, Shapley (SHAP) and Individual Conditional Expectation (ICE) analyses were performed, identifying the water-to-cement ratio, loading direction, and fibre content as key factors influencing compressive strength. Finally, a graphical user interface (GUI) has been developed for stakeholders to implement the findings of this study practically.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Conventional concrete fabrication typically involves manual mixing, casting, labour, and formworks. This method requires significant resources and generates substantial waste, making it time-consuming and costly, with labour accounting for 60–70% of the total expense1. Othuman Mydin et al.2 highlighted that such methods yield lower productivity due to labour-intensive processes, often leading to poor-quality construction. Manual labour also introduces risks like reduced efficiency from human error, safety concerns, and extended timelines, further hindering productivity3,4. Another key factor contributing to high construction costs is the use of formwork, which significantly raises expenses due to material procurement, fabrication, installation, and waste generation, making it a highly unsustainable practice5. Moreover, conventional construction significantly contributes to CO₂ emissions, largely due to the energy-intensive production of materials like cement, responsible for about 8% of global CO₂ emissions6. These economic and environmental challenges highlight the urgent need for sustainable alternatives, as emphasised by Kibert C7. who advocated incorporating sustainability in construction to mitigate the adverse impacts of traditional practices.

To advance the sustainable development of the construction sector, innovative methods are essential. Among these, 3DCP, an additive manufacturing technology, has transformed traditional construction practices. This AM technology extrudes concrete layer by layer through a nozzle, creating structures with minimal manual effort based on a digital model8. Compared to conventional methods, 3DCP offers numerous benefits, such as automation, a formwork-free process, reduced labour dependency, increased productivity, design flexibility, improved material efficiency, lower waste generation, and greater sustainability9. Research shows that 3DCP can reduce construction waste by 30–60%, labour costs by 50–80%, and production time by 50–70%10. The formwork-free approach also allows the construction of complex geometric designs that are challenging with traditional techniques9. 3DCP primarily employs two methods: extrusion-based techniques such concrete printing, contour crafting, and CONPrint3D and powder-based techniques such as emerging objects and the D-shape method. The use of 3DCP in large-scale projects has grown rapidly in recent years11.

The mix design of 3DCP is critical to its performance, with factors like extrudability, flowability, buildability, open time, and compressive strength being key areas of study12. CS, a vital mechanical property, determines the material’s ability to withstand structural loads. Due to its unique internal structure, the mechanical properties of 3DCP differ from conventional concrete, with 3DCP being significantly stronger in compression than in tension, making it ideal for sustaining compressive stresses13. Thus, investigating its compressive behaviour is essential for engineering applications. Steel rebar is required to reinforce concrete structures and prevent brittle or quasi-brittle failure14. However, incorporating steel rebar into 3DCP is challenging due to its layer-by-layer construction method, which complicates the process and undermines the automation advantages of 3DCP. To address this, researchers have explored using various short-cut fibres to reinforce 3DCP, creating fibre-reinforced concrete (FRC) that retains printability15. Commonly used fibres include carbon, glass, basalt, polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), and steel fibers15.

Numerous researchers have explored the strength properties of 3DP-FRC. Singh et al.16 studied the impact of short steel fibres, 13 mm in length and 0.2 mm in diameter, on 3DCP and found that the highest CS was achieved with 1.3% steel fibres. Xiao et al.17 investigated the use of PE fibres, noting improvements in both flexural and CS compared to standard concrete. Similarly, Sun et al.18 incorporated 9 mm PVA fibres into 3DCP and observed that higher fibre content reduced fluidity but enhanced CS, reaching up to 74.16 MPa. Pham et al.19 demonstrated that adding 6 mm steel fibres resulted in 3DCP with CS ranging between 70 and 111 MPa, a 24% improvement over fibre-free specimens. Zhu et al.20 compared various types of 3DP-FRC, including UHPC, and concluded that 3DCP with steel fibres exhibited the highest CS at 156 MPa. Overall, the addition of suitable fibre types and quantities significantly enhances the CS of 3D-printed specimens, with steel fibres being especially effective.

3DCP exhibits anisotropic behaviour in CS evaluations, with strength typically varying based on the loading direction. Due to greater longitudinal material compaction in the extrusion process, strength is generally higher in the printing direction21. According to Liu et al.22, traditional cast concrete had the highest CS under different loading directions for all testing ages. A study conducted by Pham et al.19 found the highest CS in directions perpendicular to the print head at 0°, 45°, and 90°. This was attributed to stronger interlayer connections due to pressure-induced extrusion and interaction between steel fibres and loading orientation. Most research currently focuses on experimental methods for optimising mix proportions and identifying factors affecting 3DP-FRC CS, but these methods are time-consuming and expensive. CS is affected by internal factors such as raw material selection, fibre type, dosage, and geometry, as well as external factors such as loading direction and curing time23. Despite these insights, the understanding of these factors remains limited, necessitating further investigation. The use of 3DP technology in construction is in its infancy, with no established standards, widely accepted criteria, or defined procedures. This complicates the optimisation of 3DP-FRC properties for construction applications. To address these challenges, leveraging data-driven approaches such as ML offers a promising solution. ML can predict the properties of 3DP-FRC based on influential factors, uncovering complex relationships and reducing reliance on costly and time-intensive laboratory experiments.

Literature review

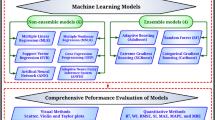

Artificial intelligence (AI) advances have led to an increase in sustainable materials and data-driven approaches in the construction industry. AI applications in construction include optimising material use, monitoring infrastructure, and improving civil engineering processes, enhancing safety and efficiency24,25. ML, a subset of AI, applies algorithms to detect patterns and relationships within data using mathematical and statistical principles. Deep learning (DL), an advanced extension of ML, leverages neural networks with multiple hidden layers to autonomously learn complex patterns and features from large-scale datasets, enabling higher accuracy and adaptability in solving complex problems as shown in Fig. 1. In recent years, ANN and other ML algorithms have proven effective for predicting various civil engineering parameters. These techniques offer reliable, cost-effective alternatives to traditional testing methods for evaluating mechanical properties of cement and concrete composites26,27. The use of ML-driven empirical models can reduce the need for time-consuming and expensive experiments in the adoption of innovative building materials. The effectiveness of ML lies in its ability to simulate complex, nonlinear, and multivariate relationships between mix composition and concrete properties28. As a result, algorithms such as ANN, GEP, and XGB have been widely used to predict concrete properties, evaluate slope failure risks, and classify soil parameters29.

Over the recent period ML techniques have been extensively utilised to predict the properties of 3DCP, as summarised in Table 1. For instance, Liu et al.30 used SVM to predict the impact of various factors on the flow behaviour and deformation of printed materials. Kumar et al.31 developed hybrid gradient boosting models optimised by metaheuristic algorithms to accurately predict the CS of high-volume fly ash self-compacting concrete with silica fume, providing a transparent tool for mix design optimisation. Similarly, Lao et al.32 employed an ANN to correlate the extrudate morphology of printed concrete with printing parameters, enabling precise control over extrudate shapes. Malik et al.33 used GPR, SVM, ANN, DT, and XGBoost to predict the anisotropic CS, slump flow, and overall CS of 3DCP. Their findings showed that GPR outperformed the other models, achieving R² values exceeding 0.91 and low prediction errors, with an average error of 9.38% for certain CS predictions. Ali et al.34 applied SVM, GPR, DT, and XGBoost to predict the flexural and tensile strength of 3DCP. Their results showed that SVM achieved the highest accuracy, with R² values of 0.90 for casted flexural strength and 0.89 and 0.88 for printed flexural strength in both directions, respectively. For tensile strength, SVM also demonstrated the highest accuracy with an R² value of 0.89. Sathvik et al.35 demonstrated that replacing 25% of cement with fly ash and 50% of river sand with manufactured sand enhanced concrete compressive strength, with the XGBoost model providing the most accurate predictions, achieving R² values of 0.9999 in training and 0.9964 in testing. These studies collectively demonstrate the extensive application of ML in predicting anisotropic mechanical properties with precision, reducing experimental effort, facilitating efficient mix design optimisation for 3DCP, and paving the way for more efficient and data-driven construction practices.

Research significance and motivation

The anisotropic nature of 3DCP, resulting from its layer-by-layer deposition process, complicates accurate prediction of key mechanical properties such as CS21. Consequently, 3DCP elements may underperform compared to those produced by conventional casting and reinforcement methods. While traditional reinforcement can be integrated into 3DCP, it introduces complexities that can undermine the automation benefits of 3DP. Fibre-reinforced concrete (FRC) addresses these limitations by enhancing strength and durability through fibre inclusion; however, optimising the composition 3DP-FRC remains challenging and requires extensive experimentation involving variables such as fibre type, dosage, and material selection. To overcome these challenges, this study applies machine learning (ML) algorithms to predict the CS of 3DP-FRC based on mixture composition. Specifically, three neural network models, Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), Radial Basis Function Neural Network (RBFNN) and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), were chosen for their superior predictive performance compared to other algorithms such as Random Forest, XGBoost, Support Vector Machines and Decision Trees43. These models effectively handle large datasets and capture complex nonlinear patterns, making them suitable for performance prediction. Recognising the “black box” nature of these models as a barrier to practical application, this study incorporates explainable machine learning techniques, including SHAP and Individual Conditional Expectation (ICE) analyses, to provide transparency by identifying the influence of input variables and visualising feature interactions. To demonstrate practical applicability of this study, an interactive Graphical User Interface (GUI) was developed, enabling stakeholders to predict outcomes and supporting data-driven decision-making. This study highlights the transformative potential of explainable machine learning in advancing efficient, resilient and sustainable construction practices.

Methodology

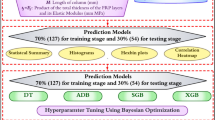

The research methodology for this study is structured into six sequential steps, as illustrated in Fig. 2. In Step 1, a dataset comprising 200 experimental results of the CS of 3DP-FRC is collected from existing literature. This is followed by Step 2, where the data undergoes correlation analysis, distribution analysis, encoding, and splitting to prepare it for further processing. In Step 3, three machine learning models are employed: MLP, CNN, and RBFNN. Subsequently, Step 4 involves evaluating the models using statistical error metrics, K-fold cross-validation, and scatter plots to ensure accuracy and reliability. Based on this validation, the Step 5 identifies the optimal model using a Taylor plot. Finally, in Step 6 the best-performing model is analysed in detail using explanatory analysis (SHAP and ICE) techniques, and the development of a GUI tailored to the selected model.

Database development and analysis

Experimental data collection

The CS of conventional concrete is typically determined through laboratory testing, involving uniaxial compression tests conducted using a universal testing machine. This process is time intensive and requires significant resources to cast, cure, and test the concrete samples for their CS44. In contrast, for 3DCP, the process involves fabricating 3DP concrete specimens, which are then subjected to compressive forces until failure. However, the accurate determination of CS of 3DCP having fibre reinforcement and various industrial wastes as a replacement of cement is particularly challenging because a lot of concrete samples having different fibre dosage and various proportions of industrial wastes needs to be tested to get a fair idea about the behaviour of CS of 3DP-FRC in relation to its mixture composition45. Printing such a vast number of samples would result in waste of resources, time, and effort. Thus, in the present study, predictive models based on ML and DL were developed to predict CS of 3DP-FRC based on its mixture composition. The data to be used for models’ development was sourced from experimental studies available in existing literature, focusing on published research that conducted CS testing of 3DCP having fibre reinforcement43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54. A total of 200 data points were compiled, representing a diverse range of experimental results. The dataset encompasses ten key input variables known to significantly influence the CS of 3DP-FRC. These variables include the W/C ratio, fly ash content, slag content, sand content, superplasticiser dosage, curing age, fiber aspect ratio, fiber type, loading direction, and fiber volume fraction. There are five distinct fiber types considered in this study and are incorporated into the database, including PE, steel, PVA, PP, and basalt fibres since these are some of the most commonly used fibres in the realm of 3DPC45. In addition, it was highlighted in the literature that the CS of 3DP-FRC is influenced by the application of three loading orientations: X, Y, and Z axes55. The X and Y axes correspond to directions aligned and perpendicular to the filament’s printing path respectively. For the purpose of incorporating the effect of this orientation into the developed predictive models, the directions X and Y are denoted as 1 and 2 in the database while the Z-axis which represents the vertical direction, is designated as 3 as shown in Fig. 5. In the same way, the different fiber types considered in this study are also encoded into numerical values as shown in Fig. 3.

Data analysis

Data distribution

Data collection is a crucial step in developing ML based predictive models. The compiled database will be used to train ML algorithms, and the accuracy of these models heavily relies on the quality of the data gathered56. Figure 4 illustrates the histogram distribution of 3DP-FRC input and output data collected from experimental results reported in the literature. The histograms also depict the cumulative frequency of the variable values, indicating the proportion of samples that exceed or fall below specific thresholds. Generally, a more robust and generalised model can only be achieved if the input and output values span a broader range. Therefore, during data collection, emphasis was placed on ensuring that input and output values covered a wide spectrum. As shown in Fig. 4, the maximum concrete age recorded in the database is 28 days, as limited studies have reported the CS of 3DP-FRC beyond this period. Conversely, the minimum concrete age is 1 day, reflecting the layer-by-layer nature of 3DP construction, where early-age CS is critical. The figure also reveals that sand, fly ash, slag, and superplasticiser content are present in varying proportions within the collected data. Having diverse values for these parameters is essential, as they significantly influence the CS of 3DP-FRC. To improve data comprehension and facilitate model training, Table 2 summarises descriptive statistics for the dataset’s input and output variables. The table presents the mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, and quartile values (25%, 50%, and 75%), offering insight into the variability and distribution of the data. The table highlights that the W/C ratio of the concrete samples used in this study ranges from 0.32 to approximately 1.5, with most values clustering around 0.47. Similarly, sand content ranges from 246 kg/m³ to over 1900 kg/m³, while superplasticiser content varies between 0 and 20 kg/m³. Fly ash and slag values are also distributed across a broad range. The output, represented by CS, ranges from 12 MPa to 153 MPa, which aligns with typical values for concrete. This extensive distribution of input and output variables ensures that the resulting predictive models are applicable to a wide array of practical scenarios.

Data correlation and partitioning

The literature highlights that the collected data should be divided into two datasets namely training and validation57. Initially, the ML model is developed using the training dataset, while the validation dataset is exclusively utilised to evaluate the model’s predictive accuracy. An 80:20 split between training and validation datasets is widely recognised as a standard practice in the literature and has been adopted in this study to maintain methodological consistency57. Similarly, it is essential to examine the interdependence among variables prior to initiating any training or testing procedures. This step is critical because a phenomenon known as “multi-collinearity” can occur when the correlation between variables exceeds their correlation with the target output, adversely affecting the performance of the ML model58. Therefore, it is imperative to examine the interdependence of all possible parameter combinations thoroughly. To facilitate this, Fig. 5 presents the Pearson correlation matrix, illustrating the relationships between dependent and independent variables. The correlation coefficient (R) ranges from − 1 to + 1, representing the strength and direction of the relationship between two variables. A positive (+) sign indicates a direct relationship, while a negative (−) sign denotes an inverse relationship. An R value of “0” signifies no correlation between the variables under consideration. Correlation values of 0.9 or higher suggest a significant relationship, and values of 0.9 or above indicate an exceptional and highly robust correlation59. It is critical to ensure that the correlation between any two variable combinations remains below 0.9 to avoid the detrimental effects of multicollinearity on model performance. As depicted in Fig. 5, all correlation values are well within this threshold, providing confidence that multicollinearity will not interfere with the predictive accuracy or reliability of the model. The correlation value between fly ash and W/C is 0.86 while it is −0.78 between sand and fly ash. Apart from that, all other values are well below the recommended threshold of 0.9. It is an indication that the collected dataset has no problem of multi-collinearity.

Model background, development and validation

Model background

RBFNN is categorised as feedforward model that is trained using supervised learning algorithms, first introduced by Broomhead and Lowe60. The structure of these neural networks consists of three main layers: an input layer, a hidden layer, and an output layer, as illustrated in Fig. 6(a). Various types of RBFs exist, including Gaussian, Hardy multi-quadratic, inverse multi-quadratic, and sigmoid functions. The Gaussian RBF is among the most commonly used, defined by a central point and a spread parameter. Following the application of RBFs to an input vector, the outputs from the hidden layer nodes are transmitted to the output layer, where they are aggregated using a simple regression process61.

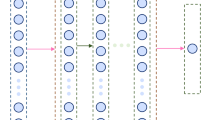

CNN is a typical deep learning neural network that has been extensively recognised as a strong method among data mining techniques. The core strength of CNNs lies in their layered architecture, as shown in Fig. 6(b), which consists of convolutional, pooling, and fully connected layers62. These layers often utilise activation functions like ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit), introducing nonlinearity to allow the network to learn complex relationships between inputs and outputs63. The application of CNNs to 3DP-FRC represents a paradigm shift in material property prediction. By leveraging their hierarchical feature extraction capabilities, CNNs provide unparalleled insights into the interplay between composition, structure, and performance. This approach not only advances the accuracy of predictive modelling but also contributes to optimising material design and structural performance in civil engineering.

MLP is a supervised feedforward neural network comprising an input layer, an output layer, and at least one hidden layer. Each layer consists of multiple neurons, with no direct connections between neurons within the same layer. Neurons in adjacent layers are fully connected through weighted connections, enabling efficient information flow. Except for the input layer, all neurons utilise nonlinear activation functions to process data64. The MLP processes data by first receiving input features through the input layer, which are then analysed and transformed by the hidden layers. The final output layer produces the predictions, achieving a multi-layered optimisation of data65. The MLP excels in modelling complex nonlinear relationships, demonstrating high parallelism and fault tolerance. It performs robustly in scenarios with noise, nonlinearity, and high-dimensional data. Additionally, the MLP’s architecture is highly adaptable, allowing modifications to the number of layers and neurons to address specific problem requirements66.

Model development

The Fig. 7 outlines a systematic approach for the development and validation of CNN, RBFNN, and MLP models, emphasising performance optimisation at each step. The process begins with the dataset being divided into training (80%) and validation (20%) subsets. The training phase starts by defining the model architecture, choosing among CNN, RBFNN, or MLP. Once the architecture is selected, hyperparameters are configured to tailor the model to the specific task. The model is then trained iteratively, with its performance evaluated against two key criteria: MAE and R2. If the MAE of the current model improves compared to the previous iteration, the R2 score is further analysed to confirm performance enhancement. This iterative process ensures continuous refinement, with model adjustments made until the optimal architecture and parameters meet the predefined performance benchmarks, validating the reliability and robustness of the developed model. Details of the model development are provided in the supplementary materials, and the hyperparameter settings for MLP, CNN, and RBFNN are presented in Table 1-B of the supplementary materials.

The Loss vs. Epochs plots for the RBFNN, MLP, and CNN models provide a comprehensive comparison of their training and validation loss behaviours as illustrated in Fig. 8. In the MLP plot (8(a)), the training and validation loss initially start at a high value approximately 60 but rapidly decrease within the first 50 epochs. After this rapid reduction, the loss curves gradually converge and stabilise around a value of 10 MAE. Notably, the training and validation loss curves are closely aligned throughout the epochs, indicating minimal overfitting and good generalisation ability. The MLP achieves convergence at a steady pace, reflecting its more complex architecture and capacity to learn intricate data relationships effectively. The RBFNN plot (8(b)) demonstrates a similar initial loss reduction within the first 50 epochs, dropping steeply from approximately 70 MAE to below 10 MAE. However, compared to the MLP, the RBFNN exhibits slightly larger oscillations in the validation loss during the early epochs, likely due to the sensitivity of the model to hyperparameter settings, such as the initialisation of centres and widths, as well as its localised activation functions. By the end of the 500 epochs, the training and validation loss curves stabilise at around 9 MAE. The proximity of the two curves suggests that the RBFNN generalises well, although the slight initial fluctuations may indicate sensitivity to hyperparameter choices such as learning rate or batch size. The CNN plot (8(c)) shows the most rapid loss reduction within the first 50 epochs, similar to the MLP, but with slightly smoother behaviour. The training loss consistently decreases to a lower final value compared to both the RBFNN and MLP, stabilising around 8 MAE. The validation loss closely follows the training loss throughout the epochs, with minimal divergence, indicating strong generalisation and robustness. The CNN’s superior performance can be attributed to its ability to extract hierarchical features, particularly in capturing complex spatial and material relationships with in 3DP-FRC, making it highly effective for CS. All models show closely aligned training and validation loss curves, indicating good generalisation, though the MLP exhibits more noticeable early fluctuations in validation loss. The RBFNN demonstrates rapid convergence and effective generalisation for simpler tasks, making it suitable for less complex datasets. The MLP, with its slightly higher final loss and early fluctuations, provides a balance between complexity and performance. The CNN, while computationally more demanding, outperforms the other models by achieving the lowest loss and demonstrating superior stability and generalisation, making it the most robust and accurate model for tasks requiring hierarchical feature extraction or more complex data representations.

Model validation

After training the algorithms, their ability to predict the desired outcome will be evaluated using testing data which was not exposed to the algorithms during training phase, by means of some error evaluation metrics commonly used in the literature. This step is particularly important to ensure that the model’s predictions are close to actual values and that there aren’t significant differences between actual and algorithmic predictions. The detailed explanation of the error metrics used to determine model accuracy is given in Table A in the appendix. Table A describes in detail the significance of each metric, the recommended criteria in the literature for the models to be acceptable, and the mathematical formulae used to determine these metrics from actual and predicted values.

Results and discussion

MLP result

The predictive capabilities of algorithms on training and validation datasets are evaluated visually in Fig. 9 using scatter plots. The proximity of data points to the linear fit line indicates the accuracy of the model’s predictions. From Fig. 9(a), it can be seen that a significant number of points of in both training and testing sets lie close to the ideal fit line and within the ± 20% band, suggesting that the model generally predicts CS values with reasonable accuracy. However, some points fall outside the ± 20% bands, indicating some outliers. The error evaluation metrics from Table 3 further support this observation. For training, MAE is 5.884, and the RMSE is 8.381, reflecting minimal deviation between predicted and actual values. The high R² value of 0.9347 also indicates a strong correlation. During validation, the MAE increases to 8.695, and the RMSE rises to 9.08, signifying a slight increase in prediction error. The R² value drops to 0.904, and the a20 index decreases to 0.79 from 0.843, highlighting a marginal decline in predictive accuracy. However, according to performance index (PI), the model is still reliable to be used for prediction since PI values are substantially lower than 0.2 for both training and testing sets. The OF value being extremely close to zero also reinforces this conclusion.

RBFNN result

The scatter plots for RBFNN in Fig. 9(b) offer insight into the model’s predictive performance. In the training plot, the data points align closely along the ideal fit line. This tight clustering indicates that the RBFNN model performs with high accuracy during training, however, the validation scatter plot displays a slightly broader spread, suggesting a modest decrease in accuracy on unseen data. This slight performance drop is typical, reflecting the challenge of generalising beyond the training dataset. The quantitative results presented in the Table 3 further substantiate the visual evidence of RBFNN’s efficacy. For training phase, RBFNN achieves a MAE of 4.902 and R² value of 0.947 in training, indicating a stronger correlation between predicted and actual values. Furthermore, 85% of RBFNN’s predictions during training fall within ± 20% of the actual values, as reflected by the a20 index of 0.85, slightly surpassing MLP. In validation, RBFNN continues to outperform MLP, with an MAE of 5.42 and R² value of 0.9488. RBFNN achieves lower PI values of 0.060 and 0.061 during training and validation respectively outperforming MLP, indicating consistently lower prediction errors. Likewise, RBFNN demonstrates enhanced predictive accuracy with OF values of 0.057 compared to MLP’s 0.0686. RBFNN consistently demonstrates lower error rates and stronger performance across both training and validation phases. Thus, RBFNN proves to be more effective than MLP, offering greater accuracy and reliability in predicting CS.

CNN result

The scatter plots for the CNN model’s training and validation phases are shown in Fig. 9(c). In the training plot, most of the predictions lie within the ± 20% deviation range. This indicates high accuracy during training, suggesting that the CNN model effectively captures the underlying data patterns. The validation plot also demonstrates a strong alignment along the ideal line, although a slight dispersion is observed. Nonetheless, a significant number of points remain within the ± 20% range, highlighting the model’s robust generalisation capabilities. Table 3 further substantiates these observations by presenting CNN’s error evaluation metrics. During training, CNN achieves a MAE of 4.712 and a RMSE of 6.510, indicating the lowest error rates among the MLP and RBFNN. This signifies that CNN predictions show minimal deviation from actual values. Additionally, CNN records the highest R² value of 0.957 during training and 0.9544 during testing, reflecting a very strong correlation between predicted and actual CS values. The a20 index of 0.918 reveals that 91.8% of CNN’s predictions fall within ± 20% of actual measurements. In validation phase, CNN maintains its superior performance, with a MAE of 5.389 and RMSE of 7.488. Furthermore, CNN achieves the lowest PI at 0.049 during training and 0.051 in validation, indicating that CNN consistently minimises overall prediction errors. Similarly, CNN’s OF value of 0.0498 further demonstrate its superior optimisation and predictive efficiency. From the scatter plots and Table 3 analysis, t can be concluded CNN is the most accurate and reliable model for CS prediction. CNN consistently demonstrates superior performance across all key metrics, outperforming MLP and RBFNN in both training and validation phases.

K-fold cross validation

The performance assessment of the developed predictive models for CS, as outlined through the error metrics in Table 3, highlights their strong potential for accurately predicting unseen data, attributed to their consistent performance during testing. To further confirm their practical applicability across diverse datasets and distributions, this study employs K-fold cross-validation, a widely accepted statistical approach. This method involves partitioning the dataset into k equal subsets, or folds67. One-fold is designated for validating the algorithm’s accuracy, while the remaining folds are collectively used for training. Unlike traditional data splitting, which evaluates models on a fixed train-test split, K-fold cross-validation provides a more comprehensive performance evaluation by allowing the model to be trained and tested on multiple dataset subsets. This iterative process ensures that each fold serves as the testing set at least once, as depicted in Fig. 10. Such an approach ensures accuracy across varying data configurations and minimises the risk of overfitting to the training data. To rigorously evaluate the robustness of employed algorithms, a 10-fold cross-validation system is utilised, employing R2 and MAE metrics to measure performance across different training and testing datasets. These metrics were selected due to their widespread use in evaluating machine learning-based predictive models (see also Table 1-A of the supplementary materials).

The result of performance assessment of three models using MAE and the R2 across 10 folds is illustrated in Fig. 11. CNN achieved the lowest MAE values across both training and validation datasets, with minimal variation across the folds as shown in Fig. 11(a) and (b). The values for CNN remained nearly constant across all folds which indicates minimal error, highlighting CNN’s stable predictive capability. RBFNN followed closely, exhibiting moderate MAE values that were slightly higher than those of CNN. However, it showed occasional variability in certain folds such as folds 5 and 9, suggesting sensitivity to specific data splits. In contrast, MLP exhibited the highest and most variable MAE values. In case of validation data, MLP displayed significant discrepancies between training and validation performance, with a noticeable spike in fold 8, highlighting its challenges with generalisation and a tendency to overfit the training data. When analysing R2, CNN again demonstrated superior performance with consistently high values as illustrated in Fig. 11(c) and (d). RBFNN achieved comparable R2 values, though it exhibited slightly greater variability across folds, particularly in folds 4 and 9. MLP, however, showed the lowest and most inconsistent R2 values, with pronounced gaps between training and validation, reflecting its instability and limited generalisation capability. The findings indicate that CNN is the most reliable model, capable of maintaining accuracy and performance across diverse data distributions and variations. RBFNN demonstrated slightly less consistent performance, while MLP requires significant optimisation to improve its generalisation and stability. Also, Table 4 summarise the mean values of MAE and R2 for both training and validation datasets across the 10 folds of K Fold cross-validation, highlighting the comparative performance of MLP, RBFNN, and CNN. These results are almost consistent with the values presented in Table 3, which summarises the error evaluation for the 80% training dataset and 20% validation dataset. The accuracy of the trained predictive models remains robust against varying data distributions and configurations.

Best model selection

The performance of RBFNN and CNN has been exceptional, as evidenced by error metrics, scatter plots, and external validation criteria. To determine the most accurate algorithm, a Taylor diagram is used to compare the performance of three models. The Taylor diagram, illustrated in Fig. 12, incorporates standard deviation and correlation coefficient to visually compare the models with the actual reference values. The actual data point is represented by a red circle, positioned at an R value of 1 and a standard deviation of approximately 32 MPa. This point serves as the benchmark for evaluating model accuracy. A model’s proximity to this point indicates its predictive capability, with closer markers demonstrating superior performance. Furthermore, the vertical or horizontal distance of a model from the reference curve reflects the variation in its standard deviation compared to the actual data. Figure 12 reveals that the CNN model, represented by a light blue square, is the closest to the actual data point, affirming its outstanding performance. Following CNN is RBFNN with an R value exceeding 0.957. Conversely, the MLP model performs least effectively among the algorithms studied. Despite these differences, all models exhibit a standard deviation of approximately 32 MPa, as their markers align closely with the reference curve. The overall ranking of the models is CNN > RBFNN > MLP. The findings from the Taylor diagram are consistent with earlier results and confirm that CNN is the most proficient algorithm among those studied.

Comparison with existing models

It is evident from the preceding sections that the ML models presented in this study are reliable for predicting the CS of concrete. However, it remains essential to compare their accuracy with closely related previous studies. This comparison ensures that the developed models are as precise as those proposed in earlier research. Since 3DCP is still in its early stages, there are limited studies available on predicting the compressive strength of 3DP-FRC. Consequently, previous studies focusing on the prediction of different 3DCP properties have been considered in this study. Table 5 provides a comparative analysis of the R2 values of the models presented in the current study alongside the earlier studies listed in Table 1. The studies presented in Table 5 demonstrate a wide range of R2 values. For instance, the study by Chang et al.38 reports a relatively low R2 of 0.75, indicating that the model’s predictive capacity was not particularly strong. In contrast, research conducted by Mütevelli Özkan and Aldemi39 and Rehman et al.36 achieved high R2 values of 0.99 and 0.982, respectively, reflecting a significantly better fit between model predictions and actual data. The current study reports an R2 value of 0.957, highlighting that it also employs a highly reliable model. Although slightly lower than the value reported by Mütevelli Özkan and Aldemi39, the current study demonstrates a near-perfect correlation, indicating that the predictive model has been effectively optimised. Overall, the table underscores that the current study ranks among the most accurate, outperforming the majority of earlier research. The relatively high coefficient of 0.957 signifies a strong degree of precision in the predictive analysis, showcasing notable advancements in methodology and substantial improvements in accuracy compared to prior studies. Although some previous studies may exhibit slightly higher accuracy, the novel deep learning algorithms implemented in this research distinguish it from earlier work. Furthermore, this study integrates comprehensive explanatory analysis techniques, including SHAP and ICE analysis, to examine the relationship between input variables and outputs, adding uniqueness and value. Additionally, the development of a GUI to apply the study’s findings in practice sets it apart from similar research. This GUI aids in reducing the trial-and-error approach traditionally used in mix design for 3DCP, contributing to more efficient and precise design processes for specific objects.

Explanatory analyses

The demand for greater transparency and interpretability in ML-based predictive models is rising alongside the widespread adoption of ML techniques69. Conducting explanatory analysis on developed ML models has become essential, as it enhances the transparency of complex black-box models by offering insights into the predictions generated by the algorithms. Within the field of civil and structural engineering, the most commonly utilised explanatory analysis methods include SHAP and ICE analysis70,71,72. Consequently, these two techniques are applied in this study to examine the influence of input variables on the strength of 3DCP. SHAP provides a comprehensive overview of the most significant variables influencing the predictions, while ICE analysis aid in visualising the relationship between the output and individual inputs.

SHAP analysis

Shapley analysis, developed by Lundberg73, enhances the interpretability of non-transparent machine learning models using coalition game theory concepts, where features act as players and model outputs as payouts. The global interpretation, emphasising the overall importance of each input feature, is commonly used and adopted in this study. Results are presented via a mean absolute SHAP plot and SHAP summary plot, as shown in Fig. 13. In Fig. 13(a), the y-axis ranks the features by importance, while the x-axis represents the mean absolute SHAP values, indicating each feature’s overall influence on the model. Higher mean absolute SHAP values signify greater influence, while lower values indicate lesser impact. The W/C ratio is the most critical factor, with the highest mean SHAP value of 31.64, due to its direct effect on porosity and density, which significantly affect concrete CS. Loading direction follows with a mean value of 2.02, influencing stress orientation and mechanical performance. Fiber volume fraction and aspect ratio also play important roles by affecting fiber distribution and interaction within the concrete matrix. Other features such as superplasticiser, age, sand, and fiber type have lesser influence, while fly ash and slag exhibit minimal impact with mean SHAP values of 0.1 and 0, respectively.

While the mean absolute SHAP plot highlights the most influential variables in predicting outcomes, the SHAP summary plot provides a more detailed understanding of how input feature values affect predictions, as illustrated in Fig. 13(b). The features are ranked from most to least influential, with dots colour-coded to represent high (red), low (blue), and moderate (purple) input values. For instance, lower W/C ratios (blue) are associated with decreased predictions, while higher ratios (red) increase predictions. Similarly, low dosages of superplasticiser and early curing ages correspond to negative SHAP values, reflecting their tendency to reduce CS due to increased water content and ongoing hydration processes. Features such as W/C exhibit a wide range of influence depending on their values, whereas others like fly ash and slag have a narrower, more consistent, yet less significant effect. These observations align with those from the mean absolute SHAP plot and offer valuable insights into the key factors driving the model’s predictions, thereby enhancing interpretability and trust in its decision-making process.

Although Fig. 13 provides a comprehensive overview of the most significant inputs influencing CS prediction, it is essential to complement this with a local interpretation to understand how the algorithm made individual predictions. Figure 14 provides detailed insight into the model’s prediction using a SHAP waterfall plot, showing a predicted CS value of 87.2 MPa. The plot shows the predicted value f(x), at the top and the base value, or average model prediction, at the bottom (69.852 MPa). Feature values for the instance are shown in grey next to each variable. The arrows indicate each input’s effect on the prediction, with red showing positive contributions and blue indicating negative impacts. Figure 14 shows that the W/C ratio has the greatest positive influence on the prediction, pushing the value higher. This aligns with the SHAP summary plot, as lower W/C ratios, such as 0.37 in this instance, correspond to higher CS. Additionally, loading in the X direction (coded as 1) and a higher curing age (28 days) also contribute positively to the predicted CS. Conversely, sand content, fly ash, and fibre volume fraction exert negative effects. Notably, the variable rankings in this local interpretation closely match those in the SHAP summary plot, confirming the model’s robustness at both local and global levels in predicting the CS of 3DCP.

ICE analysis

The results of the ICE analysis, which illustrate the relationship between input predictors and the output, are presented in Fig. 15. This figure contains ten plots, each corresponding to one of the ten input parameters used in this study to develop the ML-based predictive models. Each plot varies the value of a single input variable across its range while keeping all other variables fixed at their average values, showing how changes in that variable affect the predicted CS. The ICE curves represent the average response across all instances. Figure 15(a) shows that at lower W/C ratio, the predicted CS remains consistently high with minimal variation. However, once the W/C ratio exceeds the critical threshold of 0.4, a sharp decline in CS is observed, reflecting increased porosity and reduced structural integrity due to excess water. These results align with previous studies74,75, which demonstrate that higher W/C ratios lead to increased porosity, thereby compromising both strength and durability. 15(b) illustrates the effect of superplasticiser dosage on CS. Significant improvements occur at lower dosages, after which the predicted CS stabilises. This behaviour reflects the role of superplasticisers in reducing water content, thereby lowering the W/C ratio, improving hydration, and enhancing the uniformity and mechanical properties of the concrete mix. This aligns well with the findings of Kaya et al.76, as the addition of a superplasticiser reduces the water demand in concrete, lowering the W/C ratio. This results in denser, more compact concrete, significantly enhancing its CS.

In the same way, Figs. 15(c), (d), (e), and (f) illustrate the effect of age, sand, fiber volume fraction and the fiber type on the predicted CS respectively. The CS increases over time, with strength remaining relatively low during the initial 5 days due to slow hydration. Between days 5 and 25, CS stabilises around 69 to70 MPa, followed by a significant increase reaching approximately 72 MPa by day 28. Beyond this point, strength gains may continue but at a considerably slower and more gradual rate. This is perfectly aligned with the findings of Najvani et al.77, who demonstrated that most CS development in 3DCP occurs within the first 28 days due to cement hydration and the densification of the concrete mix. The CS of the 3DP-FRC shows a slight dependency on the quantity of sand in the mix. At lower sand contents, the CS is relatively high, reaching approximately 72.8 MPa, attributed to an optimal balance of fine aggregates enhancing packing density and cohesion within the matrix. The relationship between fibre volume fraction and CS exhibits a segmented curve with distinct trends. At zero fibre content, CS is relatively low at around 71 MPa, with minimal variation nearby. Between 0.006 and 0.010, the curve stabilises, showing consistent strength. However, a decrease in CS occurs between 0.010 and 0.015, likely due to poor fibre bonding or dispersion reducing matrix cohesion. At 0.015, a significant increase is observed, with CS peaking at approximately 77 MPa. Beyond this threshold, no further significant gains are observed, as the curve plateaus, highlighting the importance of achieving a critical fibre volume fraction for optimal mechanical performance. This is in accordance with the findings of previous literature which reported minimal strength gains at low fibre contents and improved strength at moderate levels due to enhanced crack bridging and stress distribution78,79,80. The effect of fibre type on CS is relatively minor within the studied range, yet fibres remain crucial for enhancing the mechanical properties of 3DCP. PE, steel, and PVA fibres yield similar strengths of approximately 73 MPa, while PP and basalt fibres show a slight reduction to around 70.5 MPa. These differences likely stem from variations in fibre stiffness and bonding efficiency.

Figure 15(g) illustrate that at lower aspect ratios, the CS remains relatively low, around 71 MPa. However, beyond an aspect ratio of 0.2, CS improves noticeably, reaching approximately 73 MPa, after which it plateaus. In Fig. 15(h), the effect of loading direction on the model’s output is analysed Loading in the X direction yields the highest CS, approximately 74.5 MPa, reflecting effective resistance along printed layers. Loading in the Y direction reduces CS to about 70.5 MPa, while the Z direction shows a slight recovery approximately 71 MPa, but it remains lower than the X direction. This anisotropic behaviour closely corresponds to the findings of Nima et al.81 who argued that CS is higher when the load aligns with the filament direction due to stronger alignment, and reduced strength occurs perpendicular to the layers because of weaker interlayer bonding. Figure 15(i) illustrates the effect of fly ash on compressive strength (CS). At moderate fly ash contents, up to approximately 600 kg/m³, CS remains relatively high, stabilising around 0.0060. This reflects the pozzolanic reaction producing additional calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel, which enhances mix density and strength. Beyond 600 kg/m³, CS declines significantly, stabilising near 0.0035, likely due to excessive fly ash replacing cement, reducing primary hydration products and weakening binding properties. Figure 15(j) shows that slag content from 0 to 400 kg/m³ has little effect on CS, which remains around 72 MPa. This suggests slag contributes to hydration and densification but has a less pronounced impact compared to other factors, allowing its use for sustainability without compromising mechanical performance when used optimally. These results align with previous studies82,83,84, which observed that moderate additions of supplementary cementitious materials improve performance, whereas excessive amounts weaken matrix cohesion and CS. To conclude, the findings from ICE analysis align seamlessly with those from SHAP global and local interpretations, further reinforces the reliability of the trained CNN model.

Practical implications, economic viability, and GUI

3DCP presents significant benefits for the construction industry by offering faster production times, reduced material waste, and greater design flexibility. This innovative technology aligns with sustainable construction practices by minimising resource consumption and enabling complex, customised structures that would be challenging to achieve with traditional methods. Additionally, the integration of fibre reinforcement enhances the mechanical properties of 3DCP, making it a promising alternative for structural applications. However, the widespread adoption of 3DCP is hindered by several limitations. The absence of standardised building codes, robust mix designs, and optimised reinforcement strategies poses significant challenges for ensuring consistency and reliability in 3DCP structures. The anisotropic nature of 3DCP, resulting from the layer-by-layer deposition process, further complicates the prediction of mechanical properties such as CS. These factors collectively create uncertainty, limiting the confidence of industry professionals in fully embracing 3DPC for large-scale construction projects. Experimental determination of the CS of 3DP-FRC is costly, time-consuming, and demands substantial resources. Consequently, this study utilises ML techniques including MLP, RBFNN, and CNN to predict the CS of 3DP-FRC concrete by analysing its mixture composition. The prediction models proposed in this study offer substantial practical benefits to industry professionals by enabling accurate prediction of the CS of 3DP-FRC, thereby minimising the need for extensive and resource-intensive experimental testing. Additionally, this study serves as a valuable tool for optimising the mixture design of 3DP-FRC to enhance CS leveraging insights into the relationships between input variables and CS derived from SHAP and ICE analyses. The use of explanatory analysis techniques like SHAP and ICE provides valuable insights into the key variables influencing the prediction of CS and their respective positive or negative correlations with the output. This information can be utilised to optimise the mixture design of 3DP-FRC, ensuring enhanced performance and alignment with specific project requirements. Although the models developed in this study demonstrate high accuracy, particularly with the CNN model outperforming other algorithms as outlined in Sect. "Best Model Selection", making it the most effective for output prediction. However, the black-box nature of the models poses a significant challenge for industry professionals aiming to apply it effectively. To address this and ensure the practical application of the current study findings, an interactive GUI has been developed. This GUI facilitates the prediction of CS for 3DP-FRC based on mixture composition, utilising the CNN model as illustrated in Fig. 16. Designed with accessibility in mind, the GUI allows users with limited technical expertise to input feature values and obtain predictions by simply pressing a button. The Python code for this GUI has been uploaded to an open-source repository and can be accessed at (https://github.com/Imtiaz-Iqbal/Anisotropic-CS-of-3DPC.). This GUI will enable people with limited expertise in machine learning to leverage the benefits of this study by getting the anisotropic compression strength of 3D printed concrete by simply placing the input variable values in the GUI and hitting the predict button. By bridging the gap between advanced ML models and practical application, the GUI highlights the transformative role of ML in enabling data driven decision making in the construction industry. Ultimately, it serves as a vital tool for translating the study’s outcomes into real world scenarios, supporting the optimisation and implementation of 3DP-FRC.

Conclusions

3DCP demonstrates substantial advantages over conventional construction techniques, including faster production times, reduced labour costs, minimised material waste, and enhanced design flexibility. In addition to these practical benefits, 3DCP contributes to sustainability targets by facilitating the incorporation of industrial by-products as partial replacements for cement. The mechanical performance of 3DP-FRC can also be improved significantly through the inclusion of various types of fibres within the cementitious matrix. Thus, this study was conducted to provide reliable empirical prediction models for CS of 3DP-FRC based on various ML and DL models such as RBFNN, MLP, and CNN on a database of 200 experimental instances collected from published literature. The key findings of this study are as follows:

-

The predictive accuracy of the algorithms was assessed through scatter plots, different error metrics, 10-fold cross-validation, and residual analysis. All trained models demonstrated consistent reliability in estimating the compressive strength of 3D-printed concrete.

-

The CNN algorithm outperformed the other models, achieving a testing R² of 0.95, followed by RBFNN at 0.94 and MLP at 0.90. It also yielded the lowest objective function value, 0.0498. This performance ranking was further confirmed through Taylor plot analysis.

-

The accuracy of the developed predictive models was compared with closely related previous studies, which showed that the algorithms presented in this study are more accurate than most existing machine learning models.

-

SHAP and ICE analyses were employed to identify the most influential input parameters and to examine the effect of individual inputs on the predicted outcome. The results showed that W/C, loading direction, and fibre content were among the most significant variables.

-

An interactive and user-friendly GUI has been made which can be used by different stakeholders to practically use the trained algorithms to predict the CS of 3DCP.

Limitations and future direction

While this study represents a significant contribution to the literature on the application of ML and DL algorithms for predicting key mechanical properties of concrete 3DP-FRC, it is important to acknowledge its limitations and suggest directions for future research. The study focuses on the accurate prediction of compressive strength using explainable machine learning models, providing a foundation for broader structural applications. The use of explainable AI techniques, such as SHAP values, enables the identification of critical process and material parameters influencing compressive strength. This interpretability is crucial for informing early-stage design decisions, particularly in optimising mix compositions or print parameters to achieve target strength values. Although the current study does not directly model structural behaviour or code compliance, the predictive insights generated can be integrated into structural design workflows or performance-based assessment frameworks. By bridging material-level prediction with explainability, the research contributes to safer and more informed decision-making in 3D printed concrete construction and paves the way for future studies to link machine learning-based predictions with design codes and safety standards. The predictive models developed in this study were trained on a dataset comprising 200 experimental results related to the anisotropic compressive strength of 3D-printed concrete reinforced with various fibre types. To enhance the applicability and robustness of future models, it is recommended that larger datasets with broader input and output ranges be utilised. Additionally, future research should investigate other critical mechanical and rheological properties, including flexural strength, slump flow, pumping speed, static and dynamic yield stress, and both plastic and dynamic viscosity, to gain a comprehensive understanding of the behaviour of 3DCP. Furthermore, the exploration of alternative ML techniques, such as multi-objective optimisation (MOO) and stacking ensemble models, is advised to improve prediction accuracy. Lastly, the properties of 3DCP are influenced by numerous factors beyond those considered in this study. These include material-related factors, such as cement type and fineness, superplasticiser type, accelerators, and the chemical properties of supplementary cementitious materials. Additionally, physical conditions, such as temperature, pumping speed, flow rate, and open time, can significantly impact concrete performance. Although these variables were not explicitly addressed in the current research, their inclusion in future studies is strongly recommended to develop more comprehensive and reliable predictive models.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 3DCP:

-

3D concrete printing

- 3DP-FRC:

-

3D printed fiber-reinforced concrete

- CS:

-

CS Compressive Strength

- ML:

-

Machine Learning

- DT:

-

Decision tree

- GEP:

-

Gene expression programming

- SVM:

-

Support vector machines

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural network

- GPR:

-

Gaussian Process Regression

- RF:

-

Random Forest

- NGBoost:

-

Natural Gradient Boosting

- XGBoost:

-

Extreme Gradient Boosting

- CNN:

-

Convolutional Neural Network

- MLP:

-

Multilayer Perceptron

- ICE:

-

Individual Conditional Expectation

- ReLU:

-

Rectified Linear Unit

- R:

-

Correlation coefficient

- MAE:

-

Mean Absolute Error

- R2:

-

Coefficient of determination

- a20:

-

a20-index

- RBFNN:

-

Radial Basis Functional Neural Network

- DL:

-

Deep learning

- 3DP:

-

3D printed

- AM:

-

Additive manufacturing

- FRC:

-

Fibre reinforced concrete

- PE:

-

Polyethylene

- PVA:

-

Polyvinyl Alcohol

- PP:

-

Polypropylene

- UHPC:

-

Ultra high-performance concrete

- AI:

-

Artificial intelligence

- GPR:

-

Gaussian Process Regression

- LGBM:

-

Light Gradient Boosting Machine

- ETR:

-

Extra Trees Regressor

- GUI:

-

Graphical user interface

- SHAP:

-

Shapely analysis

- RBFs:

-

Radial basis functions

- RMSE:

-

Root mean squared error

- OF:

-

Objective Function

- P1:

-

Performance Index

- W/C:

-

Water to cement ratio

References

Ning, X., Liu, T., Wu, C. & Wang, C. 3D Printing in Construction: Current Status, Implementation Hindrances, and Development Agenda, Advances in Civil Engineering, vol. 2021, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6665333

Othuman Mydin, M. A., Sani, N. M. & Phius, A. F. Investigation of industrialised building system performance in comparison to conventional construction method, MATEC Web of Conferences, vol. 10, pp. 1–6, (2014). https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/20141004001

Josa, I. & de la Fuente, A. Traditional and modern methods of construction: comparative study of the sustainability of single-family homes. Structural Concrete No June. 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.202400802 (2024).

Kang, F., Han, S., Salgado, R. & Li, J. System probabilistic stability analysis of soil slopes using Gaussian process regression with Latin hypercube sampling. Comput. Geotech. 63, 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2014.08.010 (2015).

Mao, C. et al. Cost analysis for sustainable off-site construction based on a multiple-case study in China. Habitat Int. 57, 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2016.08.002 (2016).

Jayawardana, J., Sandanayake, M., Jayasinghe, J. A. S. C., Kulatunga, A. K. & Zhang, G. A comparative life cycle assessment of prefabricated and traditional construction – A case of a developing country. J. Building Eng. 72, 106550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.106550 (2023). February.

Kibert, C. J. The next generation of sustainable construction. Building Res. Inform. 35 (6), 595–601. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613210701467040 (2007).

Liu, Y. et al. Variable fatigue loading effects on corrugated steel box girders with recycled concrete. J. Constr. Steel Res. 215, 108526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcsr.2024.108526 (2024).

El-Sayegh, S., Romdhane, L. & Manjikian, S. A critical review of 3D printing in construction: benefits, challenges, and risks. Archives Civil Mech. Eng. 20 (2), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43452-020-00038-w (2020).

Ghasemi, A. & Naser, M. Z. Tailoring 3D printed concrete through explainable artificial intelligence. Structures 56 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.07.040 (2023).

Uddin, M. N., Mahamoudou, F., Deng, B. Y., Elobaid Musa, M. M. & Tim Sob, L. W. Prediction of rheological parameters of 3D printed polypropylene fiber-reinforced concrete (3DP-PPRC) by machine learning. Mater Today Proc No Xxxx. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.03.191 (2023).

Ambily, P. S., Rajendran, N. & Kaliyavaradhan, S. K. Mix design, optimization and performance evaluation of extrusion-based 3D printable concrete, Proceedings of Institution of Civil Engineers: Construction Materials, pp. 1–19, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1680/jcoma.23.00077

Aramburu, A., Calderon-Uriszar-Aldaca, I. & Puente, I. 3D printing effect on the compressive strength of concrete structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 354 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129108 (2022).

Aramburu, A., Calderon-Uriszar-Aldaca, I. & Puente, I. Bonding strength of steel rebars perpendicular to the hardened 3D-printed concrete layers. Constr. Build. Mater. 340 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127827 (2022).

Zhang, K., Lin, W., Zhang, Q., Wang, D. & Luo, S. Evaluation of anisotropy and statistical parameters of compressive strength for 3D printed concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 440, 137417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.137417 (2024).

Singh, A., Liu, Q., Xiao, J. & Lyu, Q. Mechanical and macrostructural properties of 3D printed concrete dosed with steel fibers under different loading direction. Constr. Build. Mater. 323 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126616 (2022).

Xiao, J., Han, N., Zhang, L. & Zou, S. Mechanical and microstructural evolution of 3D printed concrete with polyethylene fiber and recycled sand at elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 293 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123524 (2021).

Sun, X., Zhou, J., Wang, Q., Shi, J. & Wang, H. PVA fibre reinforced high-strength cementitious composite for 3D printing: mechanical properties and durability. Addit. Manuf. 49 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2021.102500 (2022).

Pham, L., Tran, P. & Sanjayan, J. Steel fibres reinforced 3D printed concrete: influence of fibre sizes on mechanical performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 250 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118785 (2020).

Zhu, B. et al. Development of 3D printable engineered cementitious composites with ultra-high tensile ductility for digital construction. Mater. Des. 181 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2019.108088 (2019).

Aminpour, N. & Memari, A. Analysis of anisotropic behavior in 3D concrete printing for mechanical property evaluation, Journal of Building Engineering, vol. 99, no. October p. 111652, 2025, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.111652

Liu, C. et al. Analysis of the mechanical performance and damage mechanism for 3D printed concrete based on pore structure. Constr. Build. Mater. 314 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125572 (2022).

Wang, Y., Qiu, L., Hu, Y., Chen, S. & Liu, Y. Influential factors on mechanical properties and microscopic characteristics of underwater 3D printing concrete. J. Building Eng. 77 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107571 (2023).

Bin Inqiad, W. et al. Soft computing models for prediction of bentonite plastic concrete strength. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69271-0 (2024).

Chen, D. et al. Enhancement of underwater dam crack images using multi-feature fusion. Autom. Constr. 167, 105727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2024.105727 (2024).

Poluektova, V. A. & Poluektov, M. A. Artificial intelligence in materials science and modern concrete technologies: analysis of possibilities and prospects. Inorg. Mater. Appl. Res. 15 (5), 1187–1198. https://doi.org/10.1134/S2075113324700783 (2024).

Satyanarayana, A., Dushyanth, V. B. R., Riyan, K. A., Geetha, L. & Kumar, R. Assessing the seismic sensitivity of Bridge structures by developing fragility curves with ANN and LSTM integration. Asian J. Civil Eng. 25 (8), 5865–5888. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-024-01151-4 (2024).

Kumar, R., Rai, B. & Samui, P. Prediction of mechanical properties of high-performance concrete and ultrahigh-performance concrete using soft computing techniques: A critical review, Structural Concrete, no. February pp. 1309–1337, 2024, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.202400188

Inqiad, W. B. et al. Comparison of boosting and genetic programming techniques for prediction of tensile strain capacity of engineered cementitious composites (ECC). Mater. Today Commun. 39, 109222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2024.109222 (2024). March.

Liu, Z. et al. Modelling and parameter optimization for filament deformation in 3D cementitious material printing using support vector machine, Compos B Eng, vol. 193, no. June p. 108018, 2020, (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.108018

Kumar, R., Kumar, S., Rai, B. & Samui, P. Development of hybrid gradient boosting models for predicting the compressive strength of high-volume fly Ash self-compacting concrete with silica fume. Structures 66, 106850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2024.106850 (2024).

Lao, W., Li, M., Wong, T. N., Tan, M. J. & Tjahjowidodo, T. Improving surface finish quality in extrusion-based 3D concrete printing using machine learning-based extrudate geometry control. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 15 (2), 178–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/17452759.2020.1713580 (2020).

Malik, U. J. et al. Advancing mix design prediction in 3D printed concrete: predicting anisotropic compressive strength and slump flow. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 21, e03510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e03510 (2024).

Ali, A. et al. Machine Learning-Based predictive model for tensile and flexural strength of 3D-Printed concrete. Materials 16 (11). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16114149 (2023).

Sathvik, S. et al. Analyzing the influence of manufactured sand and fly Ash on concrete strength through experimental and machine learning methods. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88923-3 (2025).

Rehman, S. U., Riaz, R. D., Usman, M. & Kim, I. H. Augmented Data-Driven approach towards 3D printed concrete mix prediction. Appl. Sci. (Switzerland). 14 (16). https://doi.org/10.3390/app14167231 (2024).

Ma, X. R., Wang, X. L. & Chen, S. Z. Trustworthy machine learning-enhanced 3D concrete printing: Predicting bond strength and designing reinforcement embedment length, Autom Constr, vol. 168, no. PA, p. 105754, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2024.105754

Chang, Z., Wan, Z., Xu, Y., Schlangen, E. & Šavija, B. Convolutional neural network for predicting crack pattern and stress-crack width curve of air-void structure in 3D printed concrete. Eng. Fract. Mech. 271 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2022.108624 (2022).

Mütevelli Özkan, İ. G. & Aldemir, A. Machine-learning networks to predict the ultimate axial load and displacement capacity of 3D printed concrete walls with different section geometries. Structures 66, no. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2024.106879 (July, 2024).

Zhu, Z. et al. Fracture damage and energy evolution of fissured coal subject to triaxial unloading condition. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 12 (1). https://doi.org/10.1007/S40789-025-00778-1 (Dec. 2025).

Van Tran, M., Ly, D. K., Nguyen, T. & Tran, N. Robust prediction of workability properties for 3D printing with steel slag aggregate using bayesian regularization and evolution algorithm. Constr. Build. Mater. 431, 136470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.136470 (2024).

Nazar, S. et al. An evolutionary machine learning-based model to estimate the rheological parameters of fresh concrete, Structures, vol. 48, pp. 1670–1683, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.01.019

Kumar, R. et al. Estimation of the compressive strength of ultrahigh performance concrete using machine learning models, Intelligent Systems with Applications, vol. 25, no. December p. 200471, 2025, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iswa.2024.200471

Taffese, W. Z. & Espinosa-Leal, L. Multitarget regression models for predicting compressive strength and chloride resistance of concrete. J. Building Eng. 72 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.106523 (Aug. 2023).

Ukwaththa, J., Herath, S. & Meddage, D. P. P. A review of machine learning (ML) and explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) methods in additive manufacturing (3D Printing). Mater. Today Commun. 41, 110294. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MTCOMM.2024.110294 (Dec. 2024).

Ma, G., Li, Z., Wang, L., Wang, F. & Sanjayan, J. Mechanical anisotropy of aligned fiber reinforced composite for extrusion-based 3D printing. Constr. Build. Mater. 202, 770–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.01.008 (2019).

Ding, T., Xiao, J., Zou, S. & Zhou, X. Anisotropic behavior in bending of 3D printed concrete reinforced with fibers. Compos. Struct. 254, 112808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.112808 (2020). July.

Van Der Putten, J., Vijayan, R. A., De Schutter, G. & Van Tittelboom, K. Development of 3d printable cementitious composites with the incorporation of polypropylene fibers. Materials 14 (16). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14164474 (2021).

Yu, J. & Leung, C. K. Y. Impact of 3D Printing Direction on Mechanical Performance of strain-hardening Cementitious Composite (SHCC)vol. 19 (Springer International Publishing, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99519-9_24

Arunothayan, A. R. et al. Fiber orientation effects on ultra-high performance concrete formed by 3D printing. Cem. Concr Res. 143, 106384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2021.106384 (2021). no. February.

Ye, J., Cui, C., Yu, J., Yu, K. & Xiao, J. Fresh and anisotropic-mechanical properties of 3D printable ultra-high ductile concrete with crumb rubber. Compos. B Eng. 211 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2021.108639 (2021).

Pham, L., Tran, P. & Sanjayan, J. Steel fibres reinforced 3D printed concrete: influence of fibre sizes on mechanical performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 250, 118785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118785 (2020).

Yu, K., McGee, W., Ng, T. Y., Zhu, H. & Li, V. C. 3D-printable engineered cementitious composites (3DP-ECC): fresh and hardened properties. Cem. Concr Res. 143, 106388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2021.106388 (2021).

Pham, L., Lin, X., Gravina, R. J. & Tran, P. Influence of pva and pp fibres at different volume fractions on mechanical properties of 3d printed concrete, vol. 101, no. January. Springer Singapore, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-8079-6_185

Wang, C., Chen, B., Vo, T. L. & Rezania, M. Mechanical anisotropy, rheology and carbon footprint of 3D printable concrete: A review. J. Building Eng. 76, 107309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107309 (2023).

Roh, Y., Heo, G. & Whang, S. E. A survey on data collection for machine learning: A big data-AI integration perspective. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 33 (4), 1328–1347. https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2019.2946162 (2021).

Gandomi, A. H. & Roke, D. A. Assessment of artificial neural network and genetic programming as predictive tools. Adv. Eng. Softw. 88, 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2015.05.007 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Organic petrology and geochemistry of the upper Ordovician-Lower silurian Renheqiao formation shales of the Baoshan block, Western yunnan, China. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 12 (1), 49. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40789-025-00795-0 (Dec. 2025).

Sarveghadi, M., Gandomi, A. H., Bolandi, H. & Alavi, A. H. Development of prediction models for shear strength of SFRCB using a machine learning approach. Neural Comput. Appl. 31 (7), 2085–2094. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-015-1997-6 (2019).

Lowe, D. & D. S. B. and Multivariable functional interpolation and adaptive networks. Complex. Syst. 2, 321–355 (1988).

Bugmann, G. Normalized Gaussian radial basis function networks. Neurocomputing 20, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-2312(98)00027-7 (1998).

Çakiroğlu, M. A. & Süzen, A. A. Assessment and application of deep learning algorithms in civil engineering. El-Cezeri J. Sci. Eng. 7 (2), 906–922. https://doi.org/10.31202/ecjse.679113 (2020).

Celik, G. & Ozdemir, M. Determination of concrete compressive strength from surface images with the integration of CNN and SVR methods. Meas. (Lond). 238, no. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2024.115331 (April, 2024).

Naskath, J., Sivakamasundari, G. & Begum, A. A. S. A study on different deep learning algorithms used in deep neural nets: MLP SOM and DBN. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 128 (4), 2913–2936. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11277-022-10079-4 (2023).

Pinkus, A. Approximation theory of the MLP model in neural networks. Acta Numerica. 8, 143–195. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0962492900002919 (1999).

Dong, C. Compressive strength prediction of high-performance concrete using MLP model. Smart Sci. 00 (00), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/23080477.2024.2418007 (2024).

Wong, T. T. & Yeh, P. Y. Reliable Accuracy Estimates from k-Fold Cross Validation, IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng, vol. 32, no. 8, pp. 1586–1594, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2019.2912815

Wang, X., Banthia, N. & Yoo, D. Y. Reinforcement bond performance in 3D concrete printing: explainable ensemble learning augmented by deep generative adversarial networks. Autom. Constr. 158 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2023.105164 (2024).

Kashem, A. et al. Hybrid data-driven approaches to predicting the compressive strength of ultra-high-performance concrete using SHAP and PDP analyses, Case Studies in Construction Materials, vol. 20, no. February, p. e02991, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e02991

Ekanayake, I. U., Meddage, D. P. P. & Rathnayake, U. A novel approach to explain the black-box nature of machine learning in compressive strength predictions of concrete using Shapley additive explanations (SHAP). Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 16, e01059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01059 (2022).