Abstract

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a rising worldwide health concern, with an estimated 366 million cases by 2030 including 11.1 million in Bangladesh. The KCNJ11 (rs5219) polymorphism has been associated with T2DM in different populations, but its role in T2DM in Bangladesh remains quite unexplored. This study explores the genetic association between the KCNJ11 (rs5219) and T2DM and its relationship to CVD and CKD in the Bangladeshi population. A case–control study was conducted in Noakhali, Bangladesh where genomic and biochemical analyses were performed, including serum creatine, lipid profile and blood glucose levels. DNA was analyzed using ARMS-PCR and gel electrophoresis. The TT genotype was more prevalent in T2DM (68.2%), CVD (67.2%), and CKD (62.5%) groups. Significant associations (p < 0.05) were found between genotype and metabolic markers. The CT genotype in diabetic patients was showed increased risks for BMI (OR 3.43; 95% CI 1.07–1.91). For CVD patients, the TT genotype imposed higher risks for C-reactive protein (OR 1.3; 95% CI 0.79–2.03). For CKD patients, the TT genotype showed higher risk (OR 1.9; 95% CI 0.81–1.62) for serum creatinine as well as with some other parameters. The KCNJ11 (rs5219) polymorphism is significantly associated to T2DM and its complications in Bangladesh.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes affects an estimated 422 million people globally, making it a leading causes of death and morbidity1. Type 2 diabetes mellitus development is caused by both inherited and environmental factors including age, obesity, inactivity, hypertension, diet, and tobacco use2. Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) affects ten times as many people as type 1 diabetes3,4. The number of persons with diabetes has quickly increased over the last 20 years5 with its heritability, predicted to be between 20 and 80%6. Factors like insulin resistance, decreased insulin secretion, increased hepatic glucose production, sedentary lifestyle, and excessive calorie intake leading to obesity contribute to T2DM pathogenesis7. Nearly 80% of diabetes live in developing countries, with India and China contributing significantly8. Between 1980 and 2014, the number of diabetes cases doubled globally9 with diabetes being the nineth leading cause of mortality (almost 1 million) in 201710. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) reported 425 million diabetic people with an estimated $727 billion cost for its treatment and prevention in 201711. South Asians have a prevalence nearly four times higher than other ethnic groupings8. Diabetes is expected to impact 537 million people in 2021, rising to 643 million in 2030 and 783 million by 204512. SNPs have made genetic variables more important in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus13. A significant mutation, rs5219 in the KCNJ11 gene, has been associated with T2DM risk14. The KCNJ11 gene, found on chromosome 11p15.1, regulates glucose-induced insulin production and is a key candidate for T2DM15. The rs5219 polymorphism may impair KATP channel sensitivity to ATP, preventing insulin release and causing diabetes16,17,18,19. Meta-analyses demonstrate a substantial connection between rs5219 and T2DM across multiple populations, including UK20, US21, China22, Japan23, France24, Sweden25, Japan26, and Saudi Arabia27. This variant has been studied in a variety of ethnic groups, including Caucasians and Asians28, implying that it may have broader implications. HTN has been associated with KATP single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in both non-Caucasian groups (like Japanese people) and Caucasians (such Americans, Mexicans, and French people)29,30. Similarly, in East Asians, Europeans, and African Americans, KATP polymorphisms are associated different types of dyslipidemia (like increased triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels29. In Western countries, T2DM is the primary cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and renal failure, with over 40% of long-term diabetics acquiring diabetic nephropathy31,32. Furthermore, 60% of T2DM patients have hypertension contributing to nephropathy33,34. Diabetes and hypertension are linked to the development of diabetic nephropathy35. In the U.S, up to 40% of T2DM patients have indications of CKD36 whereas in India, 34.4% have diabetic renal disease37. Bangladesh is home to more than one-third of the 48 LDCs’ diabetic population, accounting 40% of diabetes in underdeveloped countries38. Bangladesh ranks second in South East Asia for adults (20–79 years) with diabetes1. The Dhaka region has seen the greatest growth in diabetes prevalence (54%), followed by Khulna (53%)39. Bangladesh will be among the top five countries with the highest diabetic populations by 203040. Diabetics in Bangladesh have a 7.5 times higher mortality rate from cardiovascular disease (CVD) than non-diabetics41. A 2013 study found that 55.2% of diabetics with less than five years had chronic kidney disease (CKD) in Bangladesh42. Significant associations between the rs5219 polymorphism and T2DM susceptibility in Asian and Caucasian subgroups underscore the need to investigate this polymorphism in other populations, including Bangladesh43. While some studies have revealed a substantial relationship between rs5219 and T2DM in Bangladesh44,45, however, previous researches have not investigated how the KCNJ11 (rs5219) polymorphism affects major biochemical markers associated with diabetes, such as fasting blood sugar (FBS), random blood sugar (RBS), serum creatinine, and lipid profiles.

These gaps highlight the need for additional research into how the KCNJ11 polymorphism contributes to T2DM and its complications, as these biochemical profiles could provide valuable insights for personalized treatment and prevention strategies in Bangladesh. To fill these gaps this study explores the association and distribution of the KCNJ11 (rs5219).

polymorphism with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and its progression to cardiovascular disease (CVD) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) in a Bangladeshi population offering valuable insights for public health activities for better clinical care of T2DM, ultimately helping to lower Bangladesh’s growing burden of diabetes and accompanying consequences.

Methodology

Ethical statement

This study adhered to all applicable ethical guidelines. The ethical committee of Noakhali Science & Technology University (Approved No: NSTU/SCI/EC/2023/208) reviewed and approved all methodologies employed in the research, ensuring compliance with the ethical principles outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. The committee ensured that the rights, safety and well-being of all participants were protected throughout the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The ethical committee’s approval permits the study to proceed without requiring additional ethical clearance.

Study population

A case–control study was conducted in Noakhali Sadar Upazila, Chattogram Division, between November 2023 to December 2024. The study included 192 cases, individuals over the age of 18 with T2DM and coexisting CVD and CKD problems. The controls were 192 healthy individuals recruited from local hospitals in Noakhali.

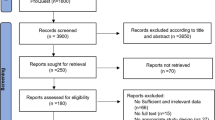

Sample size calculation and sampling

The sample size was calculated using the Cochran formula, with a 5% margin of error and a 95% confidence range. The desired population percentage is set at 50%46, since the T2DM prevalence in Noakhali is unknown. The study included 192 cases and 192 controls through stratified random sampling (Fig. 1).

Data collection

Face-to-face interviews were done with a structured questionnaire to collect data on some identified risk factors from cases and controls meeting the inclusion criteria and provided consent for voluntary participation. Anthropometric, biochemical (CRP and blood) and demographical (age, gender) data were collected. Data on the duration of T2DM and the onset of related complications (CVD and CKD) were collected exclusively from cases.

Data analysis

Anthropometric and biochemical analysis

Weight (to the nearest 0.1 kg), height (to the nearest 0.1 cm), waist and hip circumference (to the nearest 0.1 cm), and mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) (to the nearest 1 mm) were measured by trained personnel during outpatient visits (cases) and scheduled sessions (controls) using calibrated instruments and standard procedures47. Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) was calculated as waist circumference divided by hip circumference, and body mass index (BMI) as weight (kg) divided by height (m2). Systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were assessed by an automated blood pressure monitor. All anthropometric and clinical data were directly measured. Venous blood (5 mL) was collected from each participant, centrifuged for serum separation and stored at − 20 °C for biochemical analysis. FBS, RBS, total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), high density lipoprotein (HDL), and serum creatinine (SCr) levels were assessed using an enzymatic colorimetric technique except for low density lipoprotein (LDL)48. C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were collected from hospitals diagnostic reports.

Gnomic analysis

After separating serum, the blood cells were employed for DNA extraction. DNA was extracted from blood using FavorPrep™ Blood/Cultured Cell Genomic DNA Extraction Kit. Using the Amplification Refractory Mutation System Polymerase Chain Reaction (ARMS-PCR) and allele-specific primers, the rs5219 polymorphism was genotyped (Table 1)49, owing to its previous history to detect single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in blood cells from individuals in the Noakhali region50.

The PCR mixture was consisted of 12.5µl master mix, 7.5µl nuclease-free water, 1µl inward and forward primers, and 1µl extracted DNA template. Gradient PCR was initially used to determine annealing temperature (Tm). The ARMS-PCR was then performed using a PCR tube containing the PCR mixture. When the reaction was complete, the PCR tubes were stored at -20 °C for further analysis. Gel electrophoresis (45 min at 110 V and 100 current) with a 100 bp DNA ladder (cat. 11,800) and a 1% agarose gel were employed to separate PCR products. To ensure that the electrophoresis technique was consistent, samples were conducted on multiple gels. On a UV transilluminator (UVstar, USA), DNA bands were visible.

Statistical analysis

The chi-square (χ2) test was performed to analyze differences between various characteristics of individuals at risk of T2DM with a significance level set at p < 0.05. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to calculate adjusted odd ratios, controlling for gender and age.

Results

ARMS PCR analysis of KCNJ11 (rs5219) polymorphism with agarose gel electrophoresis

Tetra-primer ARMS PCR was used to identify three-point mutations in the KCNJ11 gene. PCR fragments responded as expected, with distinct sizes on agarose gel electrophoresis, allowing for evident genotype separation. Figure 2 represents DNA fragments ranging from 154 to 300 base pairs that were resolved on a 2% agarose gel. The figure displays a full ranger 100 bp DNA ladder (Fig. 2: A). The gel pattern shows lanes 1, 6, and 7 for CC homozygous wild-type samples, lanes 2, 3, and 4 for CT heterozygotes, and lane 8 for a negative control (Fig. 2: B). TT homozygous mutants were detected in other samples and included in the analysis, but are not shown in the Fig. 2.

Figure 3 demonstrates the genotype frequency of KCNJ11 (rs5219) in T2DM and associated complications (CVD and CKD) and controls. The TT genotype (homozygous) was most common in T2DM (68.2%), followed by heterozygous CT (19.3%). This pattern was similar for T2DM patients with CVD (TT: 67.20%, CT: 15.60%) and CKD (TT: 62.5%, CT: 18.80%). In contrast, CC (68.8%) genotype was most common in controls, with TT being least frequent.

Demographic distribution of T2DM and associated comorbidities (CVD and CKD) compared to controls

Figure 4 depicts the distribution of T2DM and associated consequences (CVD and CKD) across age groups, along with controls. The bulk of diabetic patients were in middle adulthood (37.5%). Controls had majority in middle adulthood (40.1%). Diabetic patients with CVD were predominantly early-adult, while those with CKD were primarily middle-adult.

Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of T2DM, its comorbidities (CVD and CKD), and the control group across gender categories. Male outnumbered female in all groups with 52.1% of T2DM cases in male compared to 47.9% in female. The control group had more balanced male-to-female ratio.

Duration of T2DM and onset of CVD and CKD complications

Figure 6 shows the distribution of diabetes duration and the timing of complications development. Nearly half of T2DM cases (47.4%) had diabetes for more than 10 years, 38% for 5–10 years, and 14.6% for less than 5 years. CVD developed in 45.3% of cases within 5–10 years of T2DM diagnosis, and 31.4% during the first 5 years. CKD onset was more afterwards, occurring in 53.1% of patients after more than 10 years and in 32.8% of cases between 5–10 years following T2DM diagnosis.

Association of KCNJ11 (rs5219) polymorphism with anthropometric and biochemical parameters in T2DM and related comorbidities (CVD and CKD)

Table 2 shows the association between the KCNJ11 (rs5219) and anthropometric measures in T2DM with CVD/CKD comorbidities. Significant associations (p < 0.05) were observed across all anthropometric markers. The TT genotype had the highest MUAC (73.50%) in T2DM, while CC genotype in controls had the highest (60.9%). MUAC was elevated in TT genotype for T2DM with CVD (66.7%) and CKD (68.9%). The TT genotype was associated with severe WHR in diabetes (59.5%). Most control with CC genotype had normal BMI. In T2DM, hypertension was common in the TT genotype for both SBP and DBP. The situation was similar for T2DM with comorbidities. In controls, CC genotype was associated with the most normal SBP and DBP.

Table 3 indicates the connection between genotype and biochemical markers in T2DM with CVD and CKD complications. (p < 0.05). Significant associations (p < 0.05) were observed across all biochemical markers. In T2DM, 70.4% of the TT genotype had diabetes (FBS). It is also similar for T2DM with CVD and CKD. However, in controls 73.9% of CC genotypes had normal FBS level. The same scenario was observed for RBS in T2DM. The TT genotype had the greatest TC (72%), TG (74%), and LDL (90%) in T2DM while CC genotype in controls had the highest HDL (88.8%). Elevated SCr was found in 71.8% of TT genotype in CKD individuals, whereas in controls CC showed the highest normal values (77.1%). In T2DM with CVD, 74.4% of the TT genotype had CRP, whereas CRP was absent in 84.2% of the CC genotype in controls.

Table 4 shows a multivariate logistic regression analysis of diabetes risk factors related with the KCNJ11 (rs5219) genotype in diabetic patients, adjusted for age and gender. The heterozygous (CT) genotype showed significant associations (p < 0.05) with all measures except for TC including 3.43-fold higher risk of BMI (OR 3.43; 95% CI 1.07–1.91) and a 2.58-fold higher risk of SBP (OR 2.58; 95% CI 1.19–2.1) than CC genotype. The CT genotype also had a 4.37-fold higher risk of TG (OR 4.37; 95% CI 1.07–1.81) and a comparable risk of SCr. In the control group, significant associations (p < 0.05) were found for WHR, MUAC, BMI, TC, TG, HDL and SCr in both genotypes, while FBS and RBS revealed no significant associations. SBP and DBP were only significantly associated with the TT genotype.

Figure 7 represents a multivariate logistic regression study of diabetes risk variables related with the KCNJ11 (rs5219) genotype in diabetic people with CVD problems, controlling for age and gender. Significant associations (p < 0.05) were found for WHR, MUAC, SBP, FBS, RBS, HDL, and SCr for both homozygous and heterozygous genotypes. The CT genotype conferred a 6.36-fold (OR 6.36; 95% CI 1.79–22.54) increased risk compared to CC for MUAC. BMI was only significant for TT genotype (OR 1.13; 95% CI 0.62–2.05). Both genotypes (TT and CT) presented nearly comparable risks for SBP, RBS, and HDL. Only the TT genotype showed a significant association (p < 0.05) with CRP (OR 1.3; 95% CI 0.79–2.03). No significant associations (p > 0.05) were found for DBP, TC, TG, and LDL in either genotype.

Figure 8 illustrates a multivariate logistic regression study of diabetes risk factors associated with KCNJ11 (rs5219) genotypes in diabetic participants with CKD complications, controlling for age and gender. Significant associations (p < 0.05) were found for DBP and LDL for both homozygous and heterozygous genotypes. BMI and TG showed no significant association (p > 0.05) with either genotype. The TT genotype raised the risk of DBP (OR 1.12; 95% CI 0.82–1.52) and LDL (OR 1.7; 95% CI 0.77–1.75) compared to CC. The TT genotype also had higher risk compared to CC genotype for MUAC (OR 1.04; 95% CI 0.74–1.46). FBS, RBS, TC and SCr were significantly associated (p-value < 0.05) with only the TT genotype, which posed 1.9-fold higher risk (OR 1.9; 95% CI 0.81–1.62) compared to CC for SCr. HDL exhibited a significant association solely for the CT genotype (OR 1.3; 95% CI 0.68–1.51).

Discussion

The mechanism behind type 2 diabetes and associated problems are still poorly understood51. Our findings highlight the KCNJ11 (rs5219) polymorphism as a key genetic risk factor for T2DM in the Bangladeshi population. The C-to-T transition at rs5219 decreases insulin production in pancreatic β-cells via affecting ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels17,52.

The predominance of long-term diabetes (> 10 years) among individuals indicates the chronic nature of T2DM53. The earlier onset of CVD problems, primarily within 5–10 years of diagnosis, is consistent with findings that CVD risk increases rapidly after T2DM development due to mechanisms such as insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction54,55. CKD problems, on the contrary, often develop later, usually after more than ten years, most likely as a result of the cumulative effects of chronic hyperglycemia and hypertension, which gradually compromise renal function56,57. These temporal trends highlight the necessity of early cardiovascular risk management in addition to long-term renal monitoring in T2DM patients58. The TT genotype was prevalent in T2DM patients (68.2%), CVD (67.2%) and CKD patients (62.5%) while the CC genotype was more common in healthy controls (68.8%), implying the TT genotype significance in T2DM and its complications. Our findings are consistent with research in China and Korea associating KCNJ11 polymorphisms to T2DM, where the TT genotype (homozygous), is related with glucose intolerance and insulin resistance59,60. Similarly, the greater frequency of the TT genotype in T2DM patients with CKD is consistent with results in Japan and China indicating KCNJ11 variant contribute to renal impairment via effects on glucose metabolism and vascular tone26,61. However, in control group the higher prevalence of the CC genotype that differs from studies in Korea and Japan, could be due to ethnic differences. The TT genotype was associated with a greater prevalence of severe WHR in T2DM patients (59.5%), suggesting a susceptibility to central obesity. In T2DM patients, the TT genotype showed the largest frequency of high MUAC (73.5%), indicating higher muscle mass and nutritional health than the CC genotype controls (60.9%) aligning with study indicating elevated MUAC means less visceral fat better metabolic62. The TT genotype in T2DM patients was related with an increased risk of obesity Class I and II, which is consistent with previous research associating KCNJ11 variants to greater fat storage63. So, the TT genotype is expected to induce insulin resistance, resulting in fat deposition, whereas the CC genotype in controls was connected to decreased obesity, indicating a protective role. Similar relationships between BMI, blood pressure, and KCNJ11 polymorphisms were found in the Emirati population64. However, a study contradicts our findings, reporting a lower frequency of the TT genotype in T2DM65, possibly due to geographical or methodological differences. Our findings align with previous studies in China66 linking KCNJ11 polymorphisms to hypertension and cardiovascular issues in T2DM. Similarly, Syrian research identified a strong relationship between KCNJ11 polymorphisms, T2DM, and obesity, with the CC genotype link to lower obesity risk67. A Jordanian study on the rs5219 variant reported protective effects of the CC genotype in healthy individuals, similar to our findings68. A meta-analysis of Caucasian and Asian populations69 confirms the association between the rs5219 variant and increased T2DM risk in obese people, supporting our claim that the TT genotype is associated with obesity. TT genotype showed high prevalence of grade 1 hypertension in T2DM (SBP 84.5%, DBP 78%) and CVD (SBP 58.6%, DBP 90.9%), consistent with study on Chinese Han population where the KCNJ11 polymorphism promotes hypertension by affecting vascular tone and blood pressure management70. The TT genotype predisposes individuals with insulin resistance and hypertension, particularly in T2DM and its comorbidities (CVD and CKD). Conversely in controls, the CC genotype had higher rates of normal blood pressure (SBP 76.9%, DBP 76.7%) and no hypertension (Grade 2 or 3), showing genomic resilience against metabolic problems, as reported in a study focusing Chinese population59. Chinese T2DM patients reported similar findings where the TT genotype had concerning high rate of hypertension and the CC genotype protecting against hypertension, emphasizes its importance in CVD and CKD like our study71.

The significant incidence of FBS (70.4% in TT carriers) and RBS (71% in TT carriers), shows an involvement in diabetes etiology, which is consistent with findings from Morocco and China on KCNJ11’s role in insulin secretion and glucose metabolism72,73, connected to KATP channels dysfunction. In contrast, the CC genotype, prevalent in hypoglycemic controls (FBS 79.9%, RBS 80%), indicates better insulin sensitivity and a lower risk of T2DM, as shown by a meta-analysis74. Patients with TT genotype showed high TC (72%), TG (74%), and very high LDL (90%), linking dyslipidemia to cardiovascular risk75. Conversely, the CC genotype in controls associated with increased HDL (88.8%), indicating a healthier lipid profile that may reduce CVD and CKD risk, supporting HDL’s preventative effect on heart health76. In North India, the TT genotype was more prevalent in T2DM patients and linked to higher FBS and TC, reflecting our results. However, unlike their study, we assess LDL levels. Their study had 77.3% male T2DM patients, compared to 52.1% in ours, indicating gender distribution differences but not affecting biochemical alignment77. Additionally, Nigerian study observed the TT genotype in both T2DM cases (45.9%) and controls (46.6%), but we found higher frequency of TT in T2DM cases (68.2%) and lowest in controls (13%) with a notable presence of CT genotype (19.3% in T2DM and 18.2% in controls). Contrary to our findings, they discovered insignificant link between the polymorphism and BMI, TC, TG, or LDL levels in T2DM78. Meanwhile, 71.8% of TT genotype patients had high SCr levels, indicating potential connection to kidney failure due to inadequate insulin secretion, whereas 77.1% of CC genotype controls had normal creatinine levels, demonstrating prevention of impaired kidney function because of greater insulin sensitivity, particularly in T2DM, where CKD is common76. Inflammatory marker CRP was present in 74.4% of T2DM patients with CVD, underscoring the link with the TT genotype. This supports findings linking CRP to an increased risk of CVD79. Conversely, CRP was absent in 84.2% of CC genotype controls, implying a potential anti-inflammatory effect due to better metabolic control. Our findings are consistent with studies in European and Hispanic populations, where KCNJ11 significantly contribute to T2DM risk, due to its effects on insulin secretion79. Furthermore, another investigation on the south Indian population80 found a link between KCNJ11 variants and T2DM-related complications reflecting our findings. The metabolic differences across genotypes are most likely due to KCNJ11 (rs5219) polymorphisms influencing insulin secretion and sensitivity.

A meta-analysis found that KCNJ11 polymorphisms increased T2DM risk, with the T-allele showing an OR of 1.5 (95% CI 1.2–1.9) across several communities. In our study the high prevalence of the TT genotype (68.2%) in T2DM population is connected to poor metabolic parameters and higher comorbidities (CVD, CKD), consistent with previous research indicating the TT genotype as a risk factor for T2DM81. In Tamil Nadu, the CC genotype was more common (77.06%) than in our study (12.5%), while CT (16.51%) and TT (6.41%) were less prevalent. In contrast, in our study TT was predominant. Their study found significant associations with uric acid, underlining the study scope because we did not consider uric acid as risk factor82. The study in West Bengal, India (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.3–2.5)83 and two independent German cohorts (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.2–2.1)84, found that KCNJ11 gene variant increase the risk of T2DM for the TT genotype across various populations, supporting our findings. A study on Mexican Mestizos found an OR of 1.9 (95% CI 1.4–2.5) for KCNJ1185, but it is unclear whether this is specific to the TT genotype. These findings are similar to ours, but still lower possibly due to external factors, lifestyle, or genetic factors placing Bangladeshi population at higher risk. Reports from West Bengal and South India highlighted the significance of KCNJ11 polymorphisms in T2DM pathogenesis, specifically their impact on glucose control, lipid metabolism, and comorbidities83,86,87. This could explain the increased OR found in our study.

Our findings on the TT genotype of KCNJ11 (rs5219) in T2DM, CVD, and CKD coincide with studies on southern Punjab and Pakistani Pashtun people, associating KCNJ11 polymorphisms to metabolic abnormalities such as higher cholesterol and triglycerides, suggesting a genetic predisposition to T2DM and associated issues88,89. However, they did not consider the various stages of hypertension, and the TT genotype was more common in T2DM patients (88%) than ours88. Studies on the Kinh Vietnamese population90 and UAE population91, and showed significant associations between KCNJ11 and T2DM90, underlining the significance of population-specific research. A Chinese She community18 confirmed KCNJ11’s effect on insulin secretion and another Chinese study found an OR of 2.0 (95% CI 1.3–3.1) for the TT genotype92, similar to our findings, but with a lesser vulnerability to metabolic diseases. In contrast, an Iranian study found insignificant association of the KCNJ11 (rs5219) polymorphism with T2DM93, indicating varying effects based on population. A Japanese study reported an OR of 1.8 (95% CI 1.2–2.5) for KCNJ11 and T2DM risk94, while studies in Mongolia (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.5–2.7)95, Tunisia (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.5–3.0)96, and Turkey (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.4–2.5)97 associated the TT genotype to poor metabolic control and comorbidities such as CVD and CKD reinforcing our study. A meta-analysis on KCNJ11 and glucose intolerance revealed an OR of 1.6 (95% CI 1.3–2.0)98, and the HUNT study in Norway found an OR of 1.7 (95% confidence interval 1.2–2.3) both suggesting the associating of the TT genotype with metabolic issues99. As the OR we found for the TT genotype was greater, suggesting a greater impact in our population. These findings reinforce KCNJ11’s significance in beta-cell activity, insulin sensitivity, and glucose metabolism across various demographics. A study in American Indian communities100 identified a link between KCNJ11 and CKD using serum creatinine aligning with our findings. and emphasizing the importance of our findings in understanding the link between KCNJ11 polymorphisms, T2DM, and CKD. A Russian study also found the TT genotype as a risk factor for diabetic nephropathy (DN) and the CC genotype as protective against CKD in T2DM, consistent with our findings101. In Iraq, a higher frequency of the TT genotype in DN patients supports our findings93. A Thai study though similarity in male patient distribution, reported contradicting result with T2DM patient showing higher BMI, FBS, and TG than controls with no significant link between T2DM and KCNJ11 polymorphism102. In Japan, KCNJ11 was associated with DN, with the CC genotype serving as a protective factor103. A study in Lucknow, India, found that the TT genotype was a risk factor for T2DM and DN, consistent with our findings, although they reported a lower TT frequency (30%) and a higher CC frequency (15.33%) than our study104.

In Bangladesh, studies found KCNJ11 (rs5219) polymorphisms contribute to T2DM and cardiovascular risks supporting our results, linking the KCNJ11’s TT genotype to poor metabolic control and comorbidities like CVD44,45. Our study distinguishes itself by incorporating a broader range of biomarkers, including glucose, lipid profiles, kidney markers like creatinine, and CRP (atherosclerosis biomarker), providing a more comprehensive view of KCNJ11’s impact on metabolism, renal health, and cardiovascular dysfunction, addressing gaps left by previous research. With the rising frequency of T2DM in Bangladesh over the last few decades39,105, our findings highlight the significance of the KCNJ11 polymorphism in the Bangladeshi community and suggest that genetic screening could be an effective technique for identifying individuals at increased risk for T2DM and associated complications including CVD and CKD. Although some private diagnostic institutions provide genetic testing, samples are frequently outsourced overseas. Public institutions including ICDDR, B, and BIRDEM perform molecular genetics research106, however, they are rarely integrated into clinical diagnosis. Over 20 universities in Bangladesh have genomic laboratories with skilled graduates107. Notably, Noakhali Science and Technology University previously examined the KCNJ11 variation45, although not as broadly as this research. Despite this capacity, institutional coordination with healthcare services is still constrained. Currently, SNP-based testing, including for KCNJ11, is mostly offered through urban-based private providers, with prices ranging from reasonable to expensive. While screening expenses range from reasonable to expensive. Research from Singapore108 and India109 shows cost-effectiveness through early risk detection. Evidence from India and Israel110, and a recent systematic review111, support population-level screening for diabetes and cardiovascular risk in low- and middle-income countries. Advancing genetic screening in Bangladesh requires public–private investment, integration of academic research into clinical practice, and broader genetics education. When combined with lifestyle interventions such as diet and physical activity, genetic testing can enable more personalized and effective strategies for T2DM prevention and management.

This study contributes importance evidence on linking the KCNJ11 (rs5219) polymorphism to T2DM and its effects in the Noakhali population of Bangladesh. By examining key clinical and biochemical indicators, the study highlights how mutation may impact cardiovascular and kidney health. Including both T2DM patients with complications and healthy controls allow for a more accurate assessment of genotype distribution and associated risks. However, some limitations must be acknowledged. The study’s small sample size and geographic focus (Noakhali, Bangladesh) limit generalizability. Its cross-sectional design restricts causal inference, and environmental factors such as diet, physical activity, and treatment history were not comprehensively assessed. These areas should be explored in future research.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides convincing confirmation that the TT genotype of the KCNJ11 rs5219 polymorphism is associated with a higher risk of T2DM and its consequences, such as CVD and CKD in the population of Noakhali, Bangladesh. These findings are comparable with those from other South Asian groups, indicating that the TT genotype is a potential genetic risk factor for T2DM. In contrast, the CC genotype appears to be protective and was more common among healthy controls. Significant relationships with blood glucose, lipid profiles, and kidney function markers validate KCNJ11 polymorphisms as possible biomarkers for T2DM and related consequences. Future study should clarify these findings in larger populations, investigate gene-environment interactions, and evaluate the functional significance of these polymorphisms.

Data availability

The corresponding author can provide the dataset produced and/or paralyzed during the current investigation upon reasonable request.

References

Atlas, D. International Diabetes Federation, 7th edn. Brussels, Belgium. International diabetes federation 33 (2015).

Kolb, H. & Martin, S. Environmental/lifestyle factors in the pathogenesis and prevention of type 2 diabetes. BMC Med. 15, 1–11 (2017).

van Susan, D. The global burden of diabetes and its complications: An emerging pandemic. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prevent. Rehabil. 17(1), s3–s8 (2010).

Guariguata, L. et al. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 103, 137–149 (2014).

Cho, N. H. et al. IDF diabetes atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 138, 271–281 (2018).

Sriwijitkamol, A., Moungngern, Y. & Vannaseang, S. Assessment and prevalences of diabetic complications in 722 Thai type 2 diabetes patients. J. Med. Assoc. Thailand 94, 168 (2011).

Al-Rubeaan, K. et al. Epidemiology of abnormal glucose metabolism in a country facing its epidemic: SAUDI-DM study. J. Diabetes 7, 622–632 (2015).

Rosella, L. C. et al. The role of ethnicity in predicting diabetes risk at the population level. Ethnicity Health 17, 419–437 (2012).

Beagley, J., Guariguata, L., Weil, C. & Motala, A. A. Global estimates of undiagnosed diabetes in adults. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 103, 150–160 (2014).

Abdul Basith Khan, M. et al. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes—Global burden of disease and forecasted trends. J. Epidemiol. Global Health 10, 107–111 (2020).

Cho, N. et al. IDF diabetes Atlas-8th. 160 (2015).

Sun, H. et al. IDF diabetes atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 183, 109119 (2022).

Basile, K. J., Johnson, M. E., Xia, Q. & Grant, S. F. Genetic susceptibility to type 2 diabetes and obesity: Follow-up of findings from genome-wide association studies. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 769671 (2014).

Sokolova, E. A., Bondar, I. A., Shabelnikova, O. Y., Pyankova, O. V. & Filipenko, M. L. Replication of KCNJ11 (p. E23K) and ABCC8 (p. S1369A) association in Russian diabetes mellitus 2 type cohort and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 10, e0124662 (2015).

Haghvirdizadeh, P. et al. KCNJ11: Genetic polymorphisms and risk of diabetes mellitus. PLoS ONE 2015, 908152 (2015).

Remedi, M. S. & Koster, J. C. K ATP channelopathies in the pancreas. J. Physiol. 460, 307–320 (2010).

Abdelhamid, I. et al. E23K variant in KCNJ11 gene is associated with susceptibility to type 2 diabetes in the Mauritanian population. Prim. Care Diabetes 8, 171–175 (2014).

Chen, G. et al. Association study of genetic variants of 17 diabetes-related genes/loci and cardiovascular risk and diabetic nephropathy in the Chinese S he population. J. Diabetes 5, 136–145 (2013).

Zhou, Y. et al. Genetic variants of OCT1 influence glycemic response to metformin in Han Chinese patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus in Shanghai. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 8, 9533 (2015).

Lyssenko, V., Nilsson, P. & Groop, L. Clinical risk factors, DNA variants, and the development of type 2 diabetes the authors reply. New England J. Med. 360, 1361–1361 (2009).

Qi, L., Van Dam, R., Asselbergs, F. & Hu, F. B. Gene–gene interactions between HNF4A and KCNJ11 in predicting Type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetic Med. 24, 1187–1191 (2007).

Liu, L. et al. Identification of susceptibility genes loci associated with type 2 diabetes. Wuhan Univ. J. Nat. Sci. 15, 171–175 (2010).

Doi, Y. et al. Impact of Kir6. 2 E23K polymorphism on the development of type 2 diabetes in a general Japanese population: The Hisayama Study. Diabetes 56, 2829–2833 (2007).

Hani, E. et al. Missense mutations in the pancreatic islet beta cell inwardly rectifying K+ channel gene (KIR6. 2/BIR): A meta-analysis suggests a role in the polygenic basis of Type II diabetes mellitus in Caucasians. Diabetologia 41, 1511–1515 (1998).

Florez, J. C. et al. Haplotype structure and genotype-phenotype correlations of the sulfonylurea receptor and the islet ATP-sensitive potassium channel gene region. Diabetes 53, 1360–1368 (2004).

Sakamoto, Y. et al. SNPs in the KCNJ11-ABCC8 gene locus are associated with type 2 diabetes and blood pressure levels in the Japanese population. J. Hum. Genet. 52, 781–793 (2007).

Alsmadi, O. et al. Genetic study of Saudi diabetes (GSSD): Significant association of the KCNJ11 E23K polymorphism with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res. Rev. 24, 137–140 (2008).

Schouten, B. J. et al. FGF23 elevation and hypophosphatemia after intravenous iron polymaltose: A prospective study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabol. 94, 2332–2337 (2009).

Smith, K. J. et al. Coronary spasm and acute myocardial infarction due to a mutation (V734I) in the nucleotide binding domain 1 of ABCC9. Int. J. Cardiol. 168, 3506–3513 (2013).

Reyes, S. et al. K ATP channel polymorphism is associated with left ventricular size in hypertensive individuals: a large-scale community-based study. Hum. Genet 123, 665–667 (2008).

Collins, A. J. et al. Excerpts from the United States Renal Data System 2004 annual data report: Atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 45, A5–A7 (2005).

Hussain, S. et al. Diabetic kidney disease: An overview of prevalence, risk factors, and biomarkers. Clin. Epidemiol. Global Health 9, 2–6 (2021).

Rasooly, R. S. et al. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Central Repositories: A valuable resource for nephrology research. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10, 710–715 (2015).

Meng, T., Qin, W. & Liu, B. SIRT1 antagonizes oxidative stress in diabetic vascular complication. Front. Endocrinol. 11, 568861 (2020).

Control, D. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. New Engl. J. Med. 329, 977–986 (1993).

Koro, C. E., Lee, B. H. & Bowlin, S. J. Antidiabetic medication use and prevalence of chronic kidney disease among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the United States. Clin. Therap. 31, 2608–2617 (2009).

Hussain, S., Habib, A. & Najmi, A. K. Limited knowledge of chronic kidney disease among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in India. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 1443 (2019).

Nordisk, N. J. B. C. P. Changing diabetes in Bangladesh through sustainable partnerships. BMJ Open 4, 1–24 (2012).

Chowdhury, M. A. B., Islam, M., Rahman, J., Uddin, M. J. & Haque, M. R. J. B. O. Diabetes among adults in Bangladesh: Changes in prevalence and risk factors between two cross-sectional surveys. BMJ Open 12, e055044 (2022).

Aguirre, F. et al. IDF diabetes atlas (2013).

Haffner, S. M., Lehto, S., Rönnemaa, T., Pyörälä, K. & Laakso, M. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. New England J. Med. 339, 229–234 (1998).

Khanam, P. et al. Hospital-based prevalence of chronic kidney disease among the newly registered patients with diabetes. J. Diabetol. 7, 2 (2016).

Cheung, C. Y. et al. The KCNJ11 E23K polymorphism and progression of glycaemia in Southern Chinese: a long-term prospective study. PLoS ONE 6, e28598 (2011).

Vaumik, A. Association of Genetic Variation in TCF7L2, SLC22A1 and KCNJ11 Genes with Risk for Type 2 Diabetes in Bangladeshi Population. (University of Dhaka, 2021).

Aka, T. D. et al. Risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular complications in KCNJ11, HHEX and SLC30A8 genetic polymorphisms carriers: A case-control study. Heliyon 7, 11 (2021).

Chaokromthong, K. & Sintao, N. Sample size estimation using Yamane and Cochran and Krejcie and Morgan and green formulas and Cohen statistical power analysis by G* Power and comparisions. Apheit. Int. J. Interdiscip. Social Sci. Technol. 10, 76–86 (2021).

Hammond, K. & Litchford, M. D. Clinical: Inflammation, physical, and functional assessments. Krause Food Nutr. Care Process 13, 165–167 (2012).

Friedewald, W. T., Levy, R. I. & Fredrickson, D. S. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 18, 499–502 (1972).

Ye, S., Dhillon, S., Ke, X., Collins, A. R. & Day, I. N. An efficient procedure for genotyping single nucleotide polymorphisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, e88–e88 (2001).

Shill, L. C. & Alam, M. R. Crosstalk between FTO gene polymorphism (rs9939609) and obesity-related traits among Bangladeshi population. Health Sci. Rep. 6, e1414 (2023).

Abubakar, I., Tillmann, T. & Banerjee, A. J. L. Global Burden of Disease 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 385, 117–171 (2015).

Bonfanti, D. H. et al. ATP-dependent potassium channels and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin. Biochem. 48, 476–482 (2015).

Diagnosis and classification of diabetes: standards of care in diabetes—2025 %J Diabetes Care. 48, S27-S49 (2025).

Fox, C. S. et al. Trends in cardiovascular complications of diabetes. JAMA 292, 2495–2499 (2004).

Beckman, J. A., Creager, M. A. & Libby, P. J. J. Diabetes and atherosclerosis: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. JAMA 287, 2570–2581 (2002).

Gross, J. L. et al. Diabetic nephropathy: Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Diabetes Care 28, 164–176 (2005).

Ritz, E. & Zeng, X. Diabetic nephropathy–epidemiology in Asia and the current state of treatment. J. Nephrol. 21, 75–84 (2011).

Zoungas, S. et al. Follow-up of blood-pressure lowering and glucose control in type 2 diabetes. New England J. Med. 371, 1392–1406 (2014).

Zhuang, L. et al. The E23K and A190A variations of the KCNJ11 gene are associated with early-onset type 2 diabetes and blood pressure in the Chinese population. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 404, 133–141 (2015).

Koo, B. et al. Polymorphisms of KCNJ11 (Kir6. 2 gene) are associated with Type 2 diabetes and hypertension in the Korean population. Diabetic Med. 24, 178–186 (2007).

Tian, D. et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms: Implications in the early diagnosis and targeted intervention of coronary microvascular dysfunction. Genes Dis. 12, 101249 (2024).

Mahan, L., Raymond, J. & Escott-Stump, S. (Elsevier, 2012).

Cauchi, S. et al. The genetic susceptibility to type 2 diabetes may be modulated by obesity status: Implications for association studies. BMC Med. Genet. 9, 1–9 (2008).

Al Ali, M. et al. Investigating the association of rs7903146 of TCF7L2 gene, rs5219 of KCNJ11 gene, rs10946398 of CDKAL1 gene, and rs9939609 of FTO gene with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Emirati population. Meta Gene 21, 100600 (2019).

Sorokina, E. Y., Pogozheva, A., Peskova, E., Makurina, O. & Baturin, A. J. Evaluation of an association between rs5219 polymorphism of kcnj11 gene and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Almanac Clin. Med. 44, 414–421 (2016).

Li, J.-Y. et al. Mutational analysis of KCNJ11 in Chinese elderly essential hypertensive patients. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 9, 153 (2012).

Makhzoom, O., Kabalan, Y. & Al-Quobaili, F. Association of KCNJ11 rs5219 gene polymorphism with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a population of Syria: A case-control study. BMC Med. Genet. 20, 1–6 (2019).

Al-Khalayfa, S. et al. Association of E23K (rs5219) polymorphism in the KCNJ11 gene with type 2 diabetes mellitus risk in Jordanian population. Hym. Gene 37, 201201 (2023).

Nielsen, E.-M.D. et al. The E23K variant of Kir6. 2 associates with impaired post-OGTT serum insulin response and increased risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 52, 573–577 (2003).

Duan, R.-F., Cui, W.-Y. & Wang, H. Association of the antihypertensive response of iptakalim with KCNJ11 (Kir6. 2 gene) polymorphisms in Chinese Han hypertensive patients. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 32, 1078–1084 (2011).

Han, Y. Y. et al. Association between potassium channel SNPs and essential hypertension in Xinjiang Kazak Chinese patients. Exp. Therap. Med. 14, 1999–2006 (2017).

Benrahma, H. et al. Association analysis of IGF2BP2, KCNJ11, and CDKAL1 polymorphisms with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a Moroccan population: A case–control study and meta-analysis. Biochem. Genet. 52, 430–442 (2014).

Hu, C. et al. PPARG, KCNJ11, CDKAL1, CDKN2A-CDKN2B, IDE-KIF11-HHEX, IGF2BP2 and SLC30A8 are associated with type 2 diabetes in a Chinese population. PLoS ONE 4, e7643 (2009).

Zeggini, E. et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data and large-scale replication identifies additional susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 40, 638–645 (2008).

Wang, Y., Zhou, X., Zhang, Y., Gao, P. & Zhu, D. L. Association of KCNJ11 with impaired glucose regulation in essential hypertension. Genet Mol. Res. 10, 1111–1119 (2011).

Barter, P. J. et al. Cholesteryl ester transfer protein: A novel target for raising HDL and inhibiting atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23, 160–167 (2003).

Raza, S. T. et al. Association of eNOS (G894T, rs1799983) and KCNJ11 (E23K, rs5219) gene polymorphism with coronary artery disease in North Indian population. Afr. Health Sci. 21, 1163–1171 (2021).

Engwa, G. A. et al. Predominance of the a allele but no association of the KCNJ11 rs5219 E23K polymorphism with type 2 diabetes in a Nigerian population (2018).

Ridker, P. M., Hennekens, C. H., Buring, J. E. & Rifai, N. C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. New England J. Med. 342, 836–843 (2000).

Reddy, S. et al. Association of ABCC8 and KCNJ11 gene variants with type 1 diabetes in south Indians. PLoS ONE 22, 1–11 (2021).

Phani, N. M. et al. Population specific impact of genetic variants in KCNJ11 gene to type 2 diabetes: A case-control and meta-analysis study. PLoS ONE 9, e107021 (2014).

Aswathi, R. et al. Influence of KCNJ11 gene polymorphism in T2DM of south Indian population. Front. Biosci. 12, 199–222 (2020).

Bankura, B. et al. Implication of KCNJ11 and TCF7L2 gene variants for the predisposition of type 2 diabetes mellitus in West Bengal, India. Diabetes Epidemiol. Manag. 6, 100066 (2022).

Fischer, A. et al. KCNJ11 E23K affects diabetes risk and is associated with the disposition index: Results of two independent German cohorts. Diabetes Care 31, 87 (2008).

Gamboa-Meléndez, M. A. et al. Contribution of common genetic variation to the risk of type 2 diabetes in the Mexican Mestizo population. Diabetes 61, 3314–3321 (2012).

Bhargave, A., Ahmad, I., Yadav, A. & Gupta, R. J. Correlating the role of KCNJ11 polymorphism (rs5219) and T2DM: A case control study. Curr. Mol. Med. 44, 175–181 (2024).

Phani, N. M. et al. Genetic variants identified from GWAS for predisposition to type 2 diabetes predict sulfonylurea drug response. Curr. Mol. Med. 17, 580–586 (2017).

Shaheen, S. et al. Association study of KCNJ11 and TCF7L2 genetic variants with type 2 diabetes mellitus in southern Punjab. Clin. Case Rep. Int. 7, 1555 (2023).

Jan, A., Khuda, F. & Akbar, R. Validation of genome-wide association studies (GWAS)-identified type 2 diabetes mellitus risk variants in Pakistani Pashtun population. J. ASEAN Fed. Endocrine Soc 38, 55 (2022).

Tran, N. Q. et al. Association of KCNJ11 and ABCC8 single-nucleotide polymorphisms with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a Kinh Vietnamese population. Medicine 101, e31653 (2022).

Al Ali, M. J. Genome architecture of Arab subpopulations of the United Arab Emirates (2018).

Xiong, C. et al. The E23K polymorphism in Kir6. 2 gene and coronary heart disease. Clin. Chim. Acta 367, 93–97 (2006).

Keshavarz, P. et al. Lack of genetic susceptibility of KCNJ11 E23K polymorphism with risk of type 2 diabetes in an Iranian population. Endocrine Res. 39, 120–125 (2014).

Omori, S. et al. Association of CDKAL1, IGF2BP2, CDKN2A/B, HHEX, SLC30A8, and KCNJ11 with susceptibility to type 2 diabetes in a Japanese population. Diabetes 57, 791–795 (2008).

Odgerel, Z. et al. Genetic variants in potassium channels are associated with type 2 diabetes in a Mongolian population. J. Diabetes 4, 238–242 (2012).

Lasram, K. et al. Evidence for association of the E23K variant of KCNJ11 gene with type 2 diabetes in Tunisian population: Population-based study and meta-analysis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 265274 (2014).

Gonen, M. S. et al. Effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms in KATP channel genes on type 2 diabetes in a Turkish population. Arch. Med. Res. 43, 317–323 (2012).

Van Dam, R. et al. Common variants in the ATP-sensitive K+ channel genes KCNJ11 (Kir62) and ABCC8 (SUR1) in relation to glucose intolerance: Population-based studies and meta-analyses 1. Diabetic Med. 22, 590–598 (2005).

Thorsby, P. et al. Comparison of genetic risk in three candidate genes (TCF7L2, PPARG, KCNJ11) with traditional risk factors for type 2 diabetes in a population-based study—The HUNT study. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 69, 282–287 (2009).

Franceschini, N. et al. The association of genetic variants of type 2 diabetes with kidney function. Kidney Int. 82, 220–225 (2012).

Zheleznyakova, A. V., Vikulova, O. K., Savelyeva, S. A., Nosikov, V. V. & Shestakova, M. V. An analysis of the association between a polymorphism rs5219 of KCNJ11 and GFR in CKD development in patients with type 2 diabetes in Russian population. Problems Endocrinol. 62, 11–12 (2016).

Rattanatham, R. et al. Association of combined TCF7L2 and KCNQ1 gene polymorphisms with diabetic micro-and macrovascular complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metabol. J. 45, 578–593 (2021).

Yoshida, T. et al. Association of genetic variants with chronic kidney disease in individuals with different lipid profiles. Int. J. Mol. Med. 24, 233–246 (2009).

Rizvi, S., Raza, S. T. & Rashid, G. Association of NPHS2, PON1 and KCNJ11 gene polymorphisms with diabetic nephropathy (2023).

Akhtar, S. et al. Prevalence of diabetes and pre-diabetes in Bangladesh: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 10, e036086 (2020).

Sultana, T. A. et al. Molecular diagnostic tests in Bangladesh: Opportunities and challenges. Pulse 8, 51–61 (2015).

Hosen, M. J. et al. Genetic counseling in the context of Bangladesh: Current scenario, challenges, and a framework for genetic service implementation. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 16, 168 (2021).

Van Nguyen, H., Finkelstein, E. A., Mital, S. & Gardner, D.S.-L. Incremental cost-effectiveness of algorithm-driven genetic testing versus no testing for Maturity Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY) in Singapore. J. Med. Genet. 54, 747–753 (2017).

Kaur, G. et al. Cost-effectiveness of population-based screening for diabetes and hypertension in India: An economic modelling study. Lancet Public Health 7, e65–e73 (2022).

Marseille, E. et al. The cost-effectiveness of gestational diabetes screening including prevention of type 2 diabetes: Application of a new model in India and Israel. J. Mater. Fetal Neonatal Med. 26, 802–810 (2013).

Sharma, M. et al. Cost-effectiveness of population screening programs for cardiovascular diseases and diabetes in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Front. Public Health 10, 820750 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: L.C.S., P.Sa.; Methodology: P.Sa., S.S.A., I.J., L.C.S.; Investigation: P.Sa., P.Se.; Formal analysis: P.Sa., S.S.A., P.Se.; Supervision: S.S.A., I.J., L.C.S.; Writing—original draft: P.Sa.; Writing—review and editing: P.Sa., S.S.A., I.J., L.C.S., P.Se.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saha, P., Alam, S.S., Jahan, I. et al. Association of KCNJ11 rs5219 polymorphism with risk of type 2 diabetes and its cardiovascular and renal complications in Noakhali, Bangladesh. Sci Rep 15, 33963 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11162-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11162-z