Abstract

In this study, we report the synthesis and biological evaluation of a novel series of chromone-isoxazoline hybrids. These conjugates were successfully synthesized through N-alkylation and 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions, and their structures were determined by spectroscopic analysis (1H and 13C-NMR), mass spectrometry (MS), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. The XRD study showed that the compound crystallizes in the monoclinic system (S.G: P21/c). The antibacterial activity of the hybrid compounds was assessed in vitro against the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 and three Gram-negative bacteria (Klebsiella aerogenes ATCC 13,048, Escherichia coli ATCC 27,853, and Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi) using the disk diffusion technique, MIC and MBC assays. The results showed that some tested compounds exhibited promising efficacy compared to the standard antibiotic chloramphenicol, underscoring their potential as antibacterial agents. These results were further validated through the determination of MIC and MBC values using the microdilution test, which showed a strong bactericidal effect of some compounds against the selected bacterial strains. Additionally, the studied compounds showed good anti-inflammatory potential by effectively inhibiting 5-LOX enzyme, with compound 5e was the most active, presenting an IC50 value of 0.951 ± 0.02 mg/mL. These in vitro results were complemented by in silico studies, including ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) predictions and molecular docking simulations. The docking analyses provided insights into the inhibition mechanisms, revealing specific interactions of the synthesized molecules with target proteins relevant to both their antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities. Finally, density functional theory (DFT)-based calculations were performed to optimize the geometric structures and analyze the structural and electronic properties of the hybrid compounds. While the results are promising, further optimization of compound potency is necessary to enhance their therapeutic potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The immune system’s response to pathogens, injured cells, or irritants manifests as inflammation, a critical process aimed at eliminating harmful sources, clearing damaged cells, and initiating tissue repair1,2. This complex response can be classified into acute and chronic inflammation, each with distinct characteristics and implications for health. Central to this inflammatory response is the enzyme lipoxygenase (5-LOX), which catalyzes the production of leukotrienes from arachidonic acid3,4,5,6. These lipid mediators play a significant role in promoting inflammation through mechanisms such as chemotaxis, increasing blood vessel permeability, and triggering pro-inflammatory reactions7. Understanding the intricacies of inflammation not only sheds light on immune responses but also highlights the need for innovative therapeutic approaches, particularly in the context of rising challenges such as antibacterial resistance8,9.

This brings us to the pressing issue of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which remains a pressing global health threat, undermining decades of progress in the treatment of infectious diseases10,11. While previous reports highlighted the alarming trajectory of AMR, recent data have made the issue even more urgent12,13. According to the latest WHO global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system (GLASS) report (WHO, 2024)14, resistance rates for Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica continue to rise, with certain regions reporting over 50% resistance to third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones. Particularly concerning is the emergence and spread of multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains, which exhibit resistance to multiple antibiotic classes and significantly complicate treatment strategies15. This rising prevalence of MDR pathogens underscores the critical need to explore alternative therapeutic agents, including bioactive compounds with broad-spectrum antimicrobial potential.

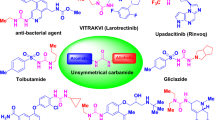

In this context, the heterocyclic family of compounds represents a highly attractive area of research for discovering promising new drug candidates capable of addressing a wide range of pathologies16. These compounds occupy a significant position in organic chemistry due to their remarkable structural characteristics and diverse applications17. Among heterocyclic compounds, isoxazolines are crucial for the synthesis of a wide range of valuable chemical molecules18,19, which are extensively utilized in various fields, particularly in the biological sciences20,21,22. These heterocycles are found in the skeletons of many insecticides and acaricides, including afoxolaner (A) and its derivatives, fluralaner (B), as well as antibacterial agents (C) and antidiabetic drugs (D) (Fig. 1)23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. Isoxazoline derivatives have continued to capture the attention of many scientists and represent a very attractive source of motivation for developing new therapeutic agents31. Many research investigations substantiate the pharmacological importance of these heterocyclic motifs32.

Furthermore, oxygen-containing heterocycles with a benzopyrone ring system form the core of several flavonoids, such as flavones and isoflavones33,34,35. The rigid bicyclic chromone framework has been identified as a preferred structure for drug development due to its utility in a wide range of pharmacologically active compounds, including anticancer agents36,37, anti-HIV, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory agents38,39,40,41,42,43.

To further enhance drug discovery, molecular hybridization remains an attractive and promising strategy for designing and developing new biologically active molecules44,45. For this reason, several research laboratories have focused on the synthesis and development of heterocycle-based hybrid compounds in the search for new drug candidates capable of addressing a variety of infections and pathologies46. Given the significance of the molecular hybridization strategy documented in the literature, along with our previous research on chromone-based heterocyclic systems aimed at discovering potent new agents47, this study aims to synthesize novel heterocyclic hybrid systems that integrate chromone and isoxazoline pharmacophores. These structures have been chosen for their promising biological activities. We will regularly evaluate their antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties, to determine their potential as innovative therapeutic agents in the treatment of infections and inflammatory diseases.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

The new chromone-isoxazoline hybrids were synthesized through an efficient and gentle 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition based approach, exploiting the high reactivity of the allyl group in compound 3 with arylnitrile oxides as 1,3-dipoles. Allylchromone 3 was synthesized following the strategy outlined in our previously published research. This approach utilizes chromone aldehyde and aminoaldehyde 1 (2-amino-4-oxo-4H-chromene-3-carbaldehyde) as precursors to prepare dipolarophile 348,49,50, as illustrated in Scheme 1, 2 and 3. The analysis of the 1H and 13C-NMR spectra of allylchromone allowed the assignment of characteristic signals to the hydrogen and carbon atoms of compound 3. In the 1H-NMR spectrum, a triplet at 4.21 ppm is attributed to the two protons of the CH2 group bound to the nitrogen atom. The two terminal protons of the allyl group appear as a doublet at 5.30 ppm, while the allylic proton –CH= appears as a broad signal at 5.91 ppm. Additionally, the 13C-NMR spectrum reveals a signal at 43.25 ppm, characteristic of the N-CH2- methylene carbon. Two other signals at 118.08 ppm and 133.71 ppm can be attributed to the allyl group carbons –CH= and =CH2, respectively51,52,53.

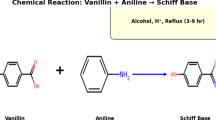

The arylnitrile oxides used as 1,3-dipoles were generated in situ by dehalogenation of the corresponding aldoximes54 (Scheme 4). The bromination of (E)-N-bromo-1-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)methanimine represents a unique case where only the formed oxime undergoes ortho bromination, unlike other oximes that do not exhibit this reactivity. In this process, the bromo group of the initial imine facilitates the formation of the oxime, which is then subjected to electrophilic substitution, favored by the activating effect of the trimethoxy groups on the aromatic ring. This specificity leads to the synthesis of (Z)-N,2-dibromo-3,4,5-trimethoxybenzimidoyl bromide, thereby illustrating how structure and substituents influence chemical reactivity and highlighting the significance of this reaction in the development of bioactive compounds55,56 (Scheme 5).

The 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction proceeded smoothly in dichloromethane in the presence of triethylamine at ambient temperature, leading to the hybrid compounds 5a-e in encouraging yields (Scheme 6). All the molecular hybrids of chromone-isoxazoline have been obtained as 3,5-disubstituted regioisomers. Their structures were identified using various spectroscopic techniques, including 1H-NMR, and 13C-NMR in CDCl3 solution, also validated by mass spectrometry and X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis.

The analysis of the 1H-NMR spectra of the synthesized chromone-isoxazoline hybrids revealed a multiplet signal observed between δ = 3.84 and δ = 3.90 ppm, which is attributed to the two CH2 protons attached to the secondary amine (–N-CH2–), and a triplet signal at δ = 10.87 ppm belonging to the proton of the (NH) group. The two diastereotopic hydrogen atoms attached to the groups C4’HaHb of the isoxazoline ring resonate as two doublets at δ = 3.21 ppm and δ = 3.58 ppm, forming an AB system due to the presence of vicinal protons (Fig. 2). A multiplet signal appeared between δ = 5.05 and δ = 5.12 ppm, indicating the existence of the methine group (CH5’) at the stereogenic center of the isoxazoline ring. The chemical shift values of protons H5’ and H4’ in the isoxazoline ring confirm the formation of the 3,5-disubstituted isoxazoline as a unique regioisomer52,57,58. Additionally, in the 13C-NMR spectra, two consecutive signals are observed at δ = 175 and δ = 189 ppm, corresponding to the carbons of the ketone (C=O) and aldehyde (CHO) groups, respectively. Another signal at δ = 43 ppm is associated with the carbon of the methylene group linked to the nitrogen atom (N-CH2), and a signal between δ = 38 and 40 ppm is attributed to the methylene carbon (C4HaHb) of the isoxazoline ring for all hybrids 5a-e. In contrast, the asymmetric carbon of the methine group (C5’) resonates at around δ = 79 ppm (Fig. 2). The chemical shift resulting from the asymmetric carbon C5’ of the isoxazoline ring (79 ppm) is in good agreement with the expected regiochemistry, as well as with published data51,59,60,61. The deshielded chemical shift observed for an aliphatic CH2 carbon of the isoxazoline ring could be attributed to an electronegative atom such as nitrogen (N). This implies that the 3,5-disubstituted regioisomer 5 was obtained in this reaction. In the case of regioisomer 5’, the signal of the stereogenic carbon would have a lower chemical shift value as it would be further from the oxygen atom (O). The spectral data support the 3,5-regioisomer and confirm the regioselectivity of the reaction. This regioselective process may be attributed primarily to the steric effects exerted by the approach of nitrile oxide 4 on both faces of allylchromone 3, resulting in the selective formation of the 3,5-regioisomer, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

The mass spectra of the new chromone-isoxazoline hybrids show a molecular ion peak [M+H]+, which corresponds precisely to the expected mass of a single molecule, confirming the chemical formulae of the proposed structures. For example, the mass spectrum of hybrid 5a shows a peak corresponding to the protonated molecular ion [M+H]+ at m/z = 417.107 is observed, confirming the molecular formula of the proposed structure [C21H15F3N2O4+H]+ (Fig. S7).

Structural study

The solid-state structure of 5d was investigated by single-crystal X-ray diffraction. The ORTEP-like diagram with the atom numbering scheme is illustrated in Fig. 4. The compound crystallized in the monoclinic P21/c space group, and the molecular structure shows the expected bond lengths for the central five-membered isoxazoline ring [N2-O8 1.433(6) Å, O8-C12 1.457(6) Å, C12-C13 1.523(6) Å, C13-C14 1.505(7) Å and C14-N2 1.281(6) Å, respectively], as observed in the literature for such compounds62. A detailed examination of the crystal structure, revealed the formation of dimeric associations between two neighboring molecules, in a head-to-tail manner, between the two chrome-4-one fragments, by π∙∙∙π interactions [Cg1(O1C1C6-C9)∙∙∙Cg2’ and Cg2(C1-C6)∙∙∙Cg1’ 3.52 Å, less than 6 Å63. Further O∙∙∙H interactions (O2∙∙∙H23B 2.63 Å, O3∙∙∙H22A 2.62 Å, O6∙∙∙H2 2.56 Å, O8∙∙∙H22C 2.43 Å cf. ΣrvdW(O,H) 2.72 Å64 are sustaining the formation of a 3D supramolecular architecture (Fig. S1a and b).

Anti-inflammatory study

The synthesized compounds 3 and 5a-e were investigated for their anti-inflammatory potential following the inhibition of 5-LOX enzyme. a key mediator in leukotriene biosynthesis. The results presented in Table 1 suggest that only the hybrid compounds bearing electron-withdrawing substituents exhibit an anti-inflammatory activity against the 5-LOX enzyme. Especialy, conjugate 5e showed the strongest 5-LOX inhibitory activity among the tested derivatives (IC50 = 0.951 ± 0.02 mg/mL), although it was less potent than of the used standard quercetin (IC50 = 0.018 ± 0.007 mg/mL; p < 0.05) (Table 1). This powerful anti-inflammatory effect observed for conjugate 5e is likely attributed to the existence of a bromine atom (R = 4-Br) at the para position of the aromatic ring. The substitution of the bromine atom by a trifluoromethyl CF3 group in hybrid compound 5a (R = 4-CF3) leads to a decrease of the efficacy. Similarly, the replacement of the para-position bromine substituent with chlorine or a nitro group at the ortho position in the hybrid compounds 5b (R = 2-Cl) and 5c (R = 2-NO2) resulted to a slight decrease in the anti-inflammatory effect, suggesting that the presence of bromine atom in the para-position of aromatic ring is most favorable for 5-LOX enzyme inhibition. However, the incorporation of the three methoxy groups as electron-donating substituents in hybrid 5d (R = 3,4,5-OCH3) resulted in no inhibition of 5-LOX enzyme, reinforcing the importance of electron-withdrawing substituents in enhancing the anti-inflammatory potential of this series. Additionally, the starting material compound 3 showed no activity against the 5-LOX enzyme. This suggests that the structural modifications enhanced the activity compared to the starting material compound 3, however, further optimization is required to achieve potency comparable to known standards. Taken together, although the synthesized compounds showed promising anti-inflammatory activity via 5-LOX inhibition, their potency is still lower compared to the reference compound quercetin. This difference may be due to structural factors affecting their binding affinity or bioavailability. To improve their efficacy, future work could explore structural optimization through medicinal chemistry approaches, such as modifying functional groups to enhance target interaction or pharmacokinetic properties. Additionally, combination strategies with other anti-inflammatory agents could be considered to achieve synergistic effects.

The tested derivatives represent promising scaffolds that require further chemical refinement and structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies to enhance their anti-inflammatory potential. Additionally, since 5-LOX represents only one pathway in the complex inflammatory cascade, future work should expand the biological evaluation to include other key mediators, such as cyclooxygenase isoforms (COX-1, COX-2) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6), to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the compounds’ anti-inflammatory mechanisms.

Due to variations in their chemical structures, the investigated substances’ inhibitory activities differed from one another, interactions with specific biological targets, or varying mechanisms of action65. The presence of functional groups, ring systems, and overall molecular geometry impact how each compound interacts with biological targets. In addition, variations in the chemicals’ Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) could impact their overall effectiveness66. A compound with superior Absorption and a longer half-life could display a better anti-inflammatory effect than one with poor pharmacokinetic properties. On the other hand, the effectiveness of each compound can be influenced by its chemical stability in physiological conditions. More stable compounds tend to maintain their activity for a longer duration, while less stable ones may break down before fully exerting their anti-inflammatory effects67,68.

Antibacterial activities

The results of the preliminary antibacterial screening of conjugates compounds 5a-e using the disc diffusion assay are listed in Table 2. Based on the outcomes, compounds 5b, 5c, and 5d were active against the tested bacterial strains. The differences observed in the inhibitory activity of the studied hybrid compounds against the tested pathogenic microorganisms, despite their structural similarity, may be attributed to the nature and electronic effects of the substituents on the phenyl ring of the isoxazoline nucleus. This observation is consistent with literature reports, which highlight the significant impact of substituent natures—whether electron-donating or electron-withdrawing—on the antibacterial action of chromone-isoxazoline hybrids against specific bacterial strains51,69. As proven by the results, certain conjugates bearing specific substituents exhibited noteworthy activity against the tested microorganisms. Among the hybrid compounds, only 5c (R = 2-NO₂) displayed significant antibacterial activity against Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 a Gram-positive bacterium, with an inhibition zone of 20.16 ± 1.34 mm. This value is particularly remarkable, as it surpasses that of the reference antibiotic, chloramphenicol, which exhibited an inhibition zone of 18.68 ± 0.33 mm. The Gram-negative bacterium Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi was inhibited exclusively by the hybrid compound 5d, which contains three methoxy groups (–OCH₃) as electron-donating substituents at the 3, 4, and 5 positions of the aromatic ring. Compound 5d (R = 3,4,5-OCH₃) showed strong antibacterial activity, with an inhibition zone of 13.04 ± 0.16 mm, compared to the reference antibiotic used (IZ = 15.00 ± 1.02 mm). In addition, conjugates 5c (R = 2-NO₂) and 5d (R = 3,4,5-OCH₃) exhibited notable antibacterial activity against the Gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli ATCC 27,853, with inhibition zones of 11.07 ± 2.25 mm and 11.38 ± 0.34 mm, respectively, compared to the reference standard (IZ = 15.70 ± 0.65 mm). Lastly, the bacterial strain Klebsiella aerogenes ATCC 13,048 exhibited sensitivity to compounds 5b (R = 2-Cl) and 5c (R = 2-NO₂), which demonstrated antibacterial activity with inhibition zones of 10.17 ± 0.20 mm and 12.00 ± 0.93 mm, respectively. Overall, conjugate 5c (R = 2-NO₂) exhibited the strongest antibacterial activity against all tested strains except Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi. This potent inhibitory effect is most likely due to the nitro (NO₂) substituent at the ortho position of the aromatic ring in the isoxazoline moiety.

The microdilution test was used to determine the MIC and MBC values of the active compounds 5b, 5c and 5d, and the results are presented in Table 3. Compound 5b exhibited a bactericidal effect against K. aerogenes, with an MIC value of 5 mg/mL and an MBC value of 10 mg/mL. The compound 5c displayed bactericidal solid effect against E. coli (MIC = MBC = 5 mg/mL), and B. subtilis (MIC = 5 mg/mL, MBC = 10 mg/mL), while showing bacteriostatic action on strain K. aerogenes with an MIC value of 2.5 mg/mL and an MBC value of 10 mg/mL. Furthermore, compound 5d showed a bactericidal effect on both bacterial strains S. enterica serotype Typhi (MIC = MBC = 2.5 mg/mL), and E. coli (MIC = 1.25 mg/mL, MBC = 2.5 mg/mL).

While compound 5c showed superior inhibition zones in the disk diffusion assay, its MIC values (5–10 mg/mL) remain relatively high compared to standard antibiotics. This discrepancy may arise from differences in diffusion properties or compound solubility, and indicates that further structural optimization is required to improve potency. These findings should therefore be viewed as initial evidence of antibacterial potential, pending further refinement. The current study is limited by the use of standard reference strains only. Future work will expand the antibacterial testing to include clinically resistant isolates, such as MRSA and P. aeruginosa, to better evaluate the spectrum and robustness of antibacterial activity.

The antibacterial effect observed in this study, although promising, was characterized by relatively high MIC values. These findings should be interpreted as preliminary, reflecting the initial screening of the synthesized compounds under the current experimental conditions. The high MIC values indicate a need for further optimization to enhance antibacterial potency. Future studies may focus on structural modification of the compounds to improve their efficacy, as well as exploring synergistic combinations with existing antibiotics to lower effective concentrations and overcome bacterial resistance.

In-silico investigations

Physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties of synthesized compounds

The synthesized compounds labeled 3, 5a, 5b, 5c, 5d, and 5e were examined for the first time by their physicochemical properties, including molecular weight, molar refractivity (MR) index, partition coefficient in (octanol/water) solvent noted by Log P. Table 4 displays the results for hydrogen bond donors (HBD) and acceptors (HBA), which demonstrates that all examined characteristics are all satisfied by the five rules of Lipinski70,71,72. They were, therefore, predicted with good physicochemical profiles, which likely make them suitable for consideration as potent agents similar to drug candidates.

Furthermore, the selected ligands were thoroughly assessed for their ADME and toxicity profiles to pinpoint any compounds with unfavorable pharmacokinetics or elevated toxicity risks. This step, conducted before costly clinical trials, contributes to significant savings in both time and resources. Evaluating these pharmacokinetic characteristics is essential, as they influence the drug’s behavior within the body and are key determinants of its overall effectiveness and safety. The results demonstrated promising absorption properties, evidenced by a high human intestinal absorption rate (HIA of 90%), along with notable permeability across the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and into the central nervous system (CNS), positive inhibition to human cytochromes of 1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, and 3A4, especially for 5a, 5b, 5c, 5d, and 5e synthesized compounds. However, toxicity profiling revealed that both compounds 5c and 5e were likely to be positive based on the results of the AMES test, indicating a potential for mutagenicity, given that the AMES test is a widely accepted test for assessing a compound’s ability to induce genetic mutations in bacterial DNA, particularly in strains of Salmonella typhimurium or Escherichia coli that have been modified to be sensitive to mutations. Although a positive AMES test result does not immediately exclude a compound from further development, it highlights the need for additional safety assessments, such as in vivo genotoxicity testing, or strategic structural modifications to eliminate mutagenic substructures and mitigate risks. It is important to note that all synthesized compounds, including 5c and 5e, were predicted to be negative for skin sensitization, suggesting a low likelihood of causing allergic skin reactions. However, both compounds 5c and 5e were predicted to be hepatotoxic, raising concerns about a potential risk of liver damage, a particularly important consideration in the context of long-term treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Although both compounds retain acceptable ADME profiles, the toxicity risks associated with them, particularly the combination of mutagenicity and hepatotoxicity in 5e, underscore the importance of early toxicological screening (Table 5). This information is essential for guiding the optimization of lead compounds, either through chemical redesign or their exclusion from preclinical development pipelines.

Moreover, Egan’s boiled egg predictive model indicates that molecule 1 (3) belongs to the yellow portion of the egg, while all other molecules are part of the white portion. As a result, molecule 3 was predicted to passively permeate the blood–brain barrier, and molecules 5a, 5b, 5c, 5d, and 5e were predicted to passively absorb by the gastrointestinal tract, as shown in Fig. 573.

Molecular docking simulations

In light of In-vitro experimental results, it was observed that molecules 5b, 5c, and 5d were provided with potential antibacterial activity against the pathogenic strains of E. coli, B. subtilis, S. typhimurium and K. aerogenes, respectively. Compounds 5a, 5b, 5c, and 5e revealed an important anti-inflammatory activity tested using 5-LOX Lipoxygenase enzyme. For these reasons, 5b, 5c, and 5d were selected for molecular docking simulation to explore their inhibition mechanisms towards four antibacterial proteins coded in the protein data bank (PDB) by 6F86, 6CGQ, 2YM9, and 1FWE, respectively. So, 5a, 5b, 5c, and 5e were selected for molecular docking directed at the 1N8Q.pdb-coded anti-inflammatory protein.

The results illustrated in Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9 confirm that the synthesized ligands 5b, 5c, and 5d exhibit significant antibacterial potential against four pathogenic bacterial strains. Specifically, these ligands demonstrated notable binding affinities (in kcal/mol) against E. coli (− 6.59, − 6.06, and − 6.21, respectively), B. subtilis (− 7.02, − 7.47, and − 6.79), S. typhimurium (− 5.89, − 6.67, and − 5.75), and K. aerogenes (− 6.19, − 6.08, and − 5.44). These strong binding energies suggest a high likelihood of biological activity, further supported by favorable molecular interactions observed at the active sites of the respective bacterial target proteins, as shown in Fig. 10. Notably, key interactions were identified with Glu50 and Gly77 residues within the 6F86.pdb protein of E. coli, Asn85 and Asn186 in B. subtilis, multiple consistent interactions with the same 6F86.pdb protein in S. typhimurium, and critical contacts involving His219 and Ala363 residues at the active site of the 1FWE.pdb protein in K. aerogenes74,75.

The results obtained in Fig. 11, confirm that chemical compounds labeled 5a, 5b, 5c, and 5e are considered suitable anti-inflammatory inhibitors against the lipoxygenase enzyme, justified by the formation of common chemical bonds including Arg775, Arg336, Leu846, and Pro718 AARs, with the lowest and closest binding energies in Kcal/mol, ranging with -7.46 kcal/mol for 5a, − 7.12 kcal/mol for 5b, − 7.28 kcal/mol for 5c, and − 7.65 kcal/mol for 5e, which confirms the molecular stability of the candidate’s ligands after being complexed to the targeted receptor of Lipoxygenase enzyme.

Density functional theory study (DFT)

Molecular geometry, frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs) analysis, and global reactivity descriptors

DFT calculations were utilized to analyze the electronic structure and reactivity of the investigated molecules. Table 6 shows the results of the energies of the HOMO and the LUMO orbitals, as well as other relevant factors calculated at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level of theory in the gas phase and water. The energy gap (∆E) denotes the energy required for electronic transitions, which are vital for molecular reactivity. In this series, compound 5c exhibits the smallest energy gap both in gas phase (2.99 eV) and water (3.75 eV), suggesting greater reactivity because of its reduced energy requirement for electron transitions. On the other hand, compounds 5d and 5b have the highest energy gap (4.55 eV and 4.77 eV), in gas phase and solution, respectively, which indicates lower reactivity and, thus, higher stability. Most compounds exhibit a slight increase in ∆E in water, likely due to dielectric stabilization reducing orbital energy differences.

The results of the computed IPs and EAs of the selected compounds listed in Table 6 indicate that the values of these two parameters span from 5.96 to 6.12 and from 1.44 to 2.97 eV, respectively, in the gas phase. However, almost all of the compounds showed a slight increase in the values of IPs and a decrease in the values of EAs were observed in water. Moreover, compound 5c has the highest electron affinity in the gas phase and water, suggesting it has the greatest tendency to gain an electron and form a negative ion. This indicates that 5c is the most reactive in accepting an electron. On the other hand, 5b and 5d are the least reactive in this regard, with the different compounds exhibiting moderate tendencies to gain electron in water.

In addition to evaluating the HOMO and LUMO, we have calculated other essential parameters to characterize the electronic and chemical properties of compounds in investigation. The chemical hardness (η) indicates the resistance of the compounds to electron exchange; its values range from 1.50 to 2.28 eV in the gas phase. Similarly, the softness (S) highlights their electronic responsiveness to external perturbations, which fall between 0.22 and 0.33 eV−1. These trends persist in water, but with slight changes indicating the solvent effect. In this regard, compound 5c has the lowest value of hardness and the highest value of softness in the gas phase and water, which makes it more reactive and less stable. Conversely, compound 5d exhibits the highest hardness and the lowest softness values in both phases, making it more stable and less reactive. So, it resists changes in its electron density and is less polarizable.

Electronegativity (χ) indicates how strongly a molecule can pull electrons towards itself when interacting with other molecules. Higher electronegativity values correspond to a more remarkable ability to attract electrons. The electronegativity values of the five compounds range from 3.72 to 4.47 eV (gas phase) and 3.67 to 4.60 eV (water), with compound 5c having the highest electronegativity value in the gas and solution states. The electronic chemical potential (μ), with values between − 4.47 and − 3.72 eV (gas phase) and − 4.60 to − 3.67 eV (water), provides insight into the charge distribution within a molecule and helps predict how the molecule will interact with other chemical species. Electrophilicity indices, ranging from 3.03 to 6.66 eV (gas phase) and 3.09 to 5.63 eV (water), measure a molecule’s ability to accept electrons during a chemical reaction. It quantifies the molecule’s propensity to act as an electrophile.

The spatial distributions of the HOMO and LUMO orbitals are illustrated in Fig. 12. Compound 5c exhibits a distinct electronic profile since its HOMO is distributed across the entire molecule, rather than covering specific substituents. This unique distribution of the electronic density likely enhances its reactivity and antibacterial activity, as widespread HOMO orbital promotes stronger interactions with bacterial cellular targets via electron donation or disruption of bacterial membranes. In contrast, the other four compounds showed that their HOMOs are mainly distributed over the substituted functional groups, indicating that these regions are subjected to nucleophilic attacks. However, Their LUMOs are mainly concentrated on the carbonyl groups of the pyran ring and aldehyde moieties, making these sites regions for electrophilic interactions. Moreover, 5c further distinguishes itself through its LUMO distribution, which is placed on its substituted groups rather than on carbonyls. This shows 5c’s unique reactivity and explains its superior antibacterial performance compared to the other compounds.

Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surfaces

The MEP is a great tool for visualizing regions of a molecule that are likely to be sites of electrophilic or nucleophilic attack. In most MEPs, the red region (negative) indicates areas of high electron density, which are attractive to electrophiles, while the blue regions (positive) indicate areas of low electron density, which are attractive to nucleophiles. The MEP helps in understanding the reactivity, polarity, and intermolecular interactions of a molecule by illustrating its size, shape, and the distribution of electrostatic potential. Figure 13 depicts the MEP of the studied compounds in water. The most negative region is concentrated around the two carbonyl groups linked to the cycle, indicating that this region is favorable for electrophilic attacks. In contrast, the positive potentials are primarily found around the hydrogens of the isooxazoline cycle, suggesting that this area is suitable for nucleophilic attacks.

Non-covalent interactions (NCI) analysis

The NCI analysis is a computational technique used to study and visualize various non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions, and π-π stacking. This analysis helps in understanding the nature, strength, and role of these interactions in molecular systems. The different colors of isosurfaces in NCI plots are classified based on the type and strength of interactions: blue indicates strong, attractive interactions, green denotes van der Waals interactions, and red signifies strong repulsion76,77. Therefore, the appearance of green and red isosurfaces in Fig. 14 designates van der Waals and steric interactions. The absence of blue suggests that the five compounds do not engage in intramolecular hydrogen bonding.

Electron localized function (ELF)

Covalent bonding can be studied by topological analyses of the ELF, which identify regions of molecular space where the likelihood of discovering electron pairs is high78. A two-dimensional representation of this is shown in Fig. 15.

Figure 15 shows a two-dimensional (2D) representation of the ELF on a scale from 1.0 to 0.0. The color codes begin with red for high ELF levels, progress through yellow to green for moderate levels, and end with blue hues for low ELF levels. Low ELF values indicate little electron repulsion, while high ELF values indicate more electron localization in a specific area78.

The 5a to 5e molecules in Fig. 15 have red patches focused on the oxygen atoms, indicating that electron localization is most noticeable in the oxygen atom region. The presence of blue areas in these molecules suggests the presence of both electrophilic and nucleophilic sites.

Materials and methods

General information

All chemicals used were of analytical grade and were used without further purification and were purchased from commercial suppliers. The progress of the reactions was monitored by TLC (Merck, silica gel 60 F254), and spots were visualized under UV light (Vilber Lourmat, VL-215.LC). The melting points were determined in capillaries with an Electrothermal 9100 instrument. NMR spectra (1D, 2DHSQC and 2D-HMBC) were recorded at room temperature on Bruker Avance instruments (1H-NMR/13C-NMR: 400 MHz/100 MHz or 600 MHz/150 MHz) in solution (deuterated solvents (CDCl3 or DMSO). For the 13C NMR spectra, the APT experiment was used, which provide information on the multiplicity of the 13C signals (CH3, CH2, CH and Cq). The chemical shifts are euhxpressed in ppm and the coupling constants J are expressed in Hertz (Hz). HRMS spectra recorded on Thermo Scientific LTQ Orbitrap XL.

Synthesis procedures

Preparation of 4-oxo-2-(prop-2-yn-1-ylamino)-4H-chromene-3-carbaldehyde 3

In a 100-ml flask, 1 mol of compound 2 and 1.2 mol of potassium bicarbonate were dissolved in 20 ml of N,N Dimethylformamide with magnetic stirring for 20 min. Then, one mole of allyl bromide and 0.5 mol of tetrabutylammonium bromide were added. The reaction mixture was continuously stirred, and the progress was monitored using TLC. After completion, the mixture was poured into ice-cold water. The resulting solid was filtered and purified by recrystallization in ethanol to obtain compound 3.

Brown solid, yield (97%), m.p = 161 °C; 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz δ in ppm): 10.67 (s, 1H, NH), 10.24 (s, 1H, CHO), 8.22 (dd, Ar–H, J = 12.04, 4.24 Hz), 7.61 (tt, Ar–H, J = 8.64, 1.64 Hz), 7.38 (t, Ar–H, J = 7 Hz), 7.29 (d, Ar–H, J = 7.28 Hz), 5.92–5.99 (m, -CH=), 5.32 (dd, –NCH2, J = 19.8, 10.24 Hz), 4.21 (t, =CH2, J = 5.76 Hz). 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz δ in ppm): 189.58 (CHO), 175.83 (C=O), 164.40 (C2), 153.31, 133.72 (–CH=), 131.84, 126.33, 125.77 122.79, 118.09, 116.61 (=CH2), 99.49 (C3), 43.26 (–NCH2). (See GCMS). Mass found for (C13H11NO3): 228.

Reaction of 2-(allylamino)-4-oxo-4H-chromene-3-carbaldehyde 3 with arylnitrile oxides 4a-e

To a solution of 3 (1 equivalent) in 20 ml of dichloromethane, arylnitrile oxides 4 (1.4 equivalents) were added with stirring. After 20 min, two to four drops of trimethylamine (Et3N) were added to the mixture. The reaction progress was monitored by TLC. The mixture was then extracted with CH2Cl2, evaporated, and dried. The resulting crude product was subjected to column chromatography (using silica gel and a toluene/ether ratio of 8/2) to yield isoxazoline 5(a-e).

-

a)

4-oxo-2-(((3-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-4,5-dihydroisoxazol-5-yl)methyl)amino)-4H-chromene-3-carbaldehyde 5a.

Solid white, yield (83%), m.p = 204 °C, 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz δ in ppm): 10.87 (t, NH, J = 7.98 Hz), 10.21 (s, CHO), 8.21 (dd, Ar–H, J = 7.68, 1.5 Hz), 7.78 (d, Ar–H, J = 8.22 Hz), 7.67 (d, Ar–H, J = 8.16 Hz ), 7.62 (tt, Ar–H, J = 8.34, 1.74 Hz), 7.40 (t, Ar–H, J = 7.2 Hz), 5.10 (six, H5’), 3.88 (t, –NCH2, J = 5.94 Hz), 3.59–3.21 (dd, 2H4’iso, J = 16.68, 10.62–16.68, 6.78 Hz). 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz δ in ppm): 189.83 (CHO), 175.77 (C=O), 164.65 (C2), 155.54, 153.36 (C3’), 133.95, 132.36, 132.23, 127.18, 126.54, 126.10, 125.97, 122.97, 116.70, 99.74 (C3), 79.17 (C5’iso), 43.87 (–NCH2), 38.03 (C4’iso). HRMS (m/z) [C21H15F3N2O4+H]+: Mass calculated for: 417.1057, Mass found 417.1067.

-

b)

2-(((3-(2-chlorophenyl)-4,5-dihydroisoxazol-5-yl)methyl)amino)-4-oxo-4H-chromene-3-carbaldehyde 5b.

Solid white, yield (78%), m.p = 167 °C, 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz δ in ppm): 10.87 (t, NH, J = 5.1 Hz), 10.21 (s, CHO), 8.22 (dd, Ar–H, J = 7.8, 1.68 Hz), 7.62–7.63 (m, Ar–H), 7.42 (t, Ar–H, J = 12 Hz ), 7.38 (tt, Ar–H, J = 7.98, 1.8 Hz), 7.32 (tt, Ar–H, J = 8.7, 1.2 Hz), 5.05 (six, H5’), 3.88 (m, –NCH2), 3.72–3.36 (dd, 2H4’iso, J = 17.4, 10.56–17.28, 6.36 Hz). 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz δ in ppm): 190.00 (CHO), 176.02 (C=O), 165.17 (C2), 156.74, 153.60 (C3’), 156.7, 153.60, 134.11, 133.18, 131.62, 131.04, 130.92, 128.70, 127.54, 126.74, 126.23, 123.23, 116.94, 99.96 (C3), 79.17 (C5’iso), 44.04 (–NCH2), 40.98 (C4’iso). HRMS (m/z) [C20H15ClN2O4+H]+: Mass calculated for: 383.0793, Mass found 383.0803.

-

c)

2-(((3-(2-nitrophenyl)-4,5-dihydroisoxazol-5-yl)methyl)amino)-4-oxo-4H-chromene-3-carbaldehyde 5c.

Solid brown, yield (93%), m.p = 158 °C, 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz δ in ppm): 10.87 (t, NH, J = 7.68 Hz), 10.26 (s, CHO), 8.22 (d, Ar–H, J = 11.76 Hz ), 8.13 (d, Ar–H, J = 12.18 Hz ), 7.73 (tt, Ar–H, J = 11.22, 2.4 Hz), 7.58–7.65 (m, 3Ar-H), 7.41 (t, Ar–H, J = 10.92 Hz), 7.35 (d, Ar–H, J = 12.48 Hz), 5.12 (six, H5’), 3.88–4.01(m, –NCH2), 3.13–3.47 (dd, 2H4’iso, J = 25.26, 15.66–25.26, 8.4 Hz). 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz δ in ppm): 189.74 (CHO), 175.81 (C=O), 164.86 (C2), 155.47, 153.29 (C3’), 134.01, 133.85, 131.27, 131.06, 126.32, 125.88, 125.24, 125.08, 122.82, 116.78, 99.63 (C3), 79.23 (C5’iso), 43.58 (–NCH2), 40.73 (C4’iso). HRMS (m/z) [C20H15N3O6+H]+: Mass calculated for: 394.1034, Mass found 394.1030.

-

d)

2-(((3-(2-bromo-3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydroisoxazol-5-yl)methyl)amino)-4-oxo-4H-chromene-3-carbaldehyde 5d.

Crystal white, yield (90%), m.p = 144 °C, 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz δ in ppm): 10.89 (t, NH, J = 9.06 Hz), 10.27 (s, CHO), 8.24 (dd, Ar–H, J = 11.7, 2.52 Hz), 7.65 (tt, Ar–H, J = 10.86, 2.64 Hz), 7.42 (tt, Ar–H, J = 11.16, 1.62 Hz), 7.35 (d, Ar–H, J = 10.92 Hz), 6.94 (s, Ar–H), 5.11 (six, H5’), 3.95–3.93 (m, –NCH2), 3.93, 3.92, 3.89 (s, 3OCH3), 3.79–3.39 (dd, 2H4’iso, J = 26.04, 15.09–26.04, 9.18 Hz). 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz δ in ppm): 189.65 (CHO), 175.73 (C=O), 164.83 (C2), 157.87, 153.23 (C3’), 153.23, 153.00, 151.34, 144.57, 133.84, 125.94, 125.71, 122.81, 116.63, 109.67, 108.96, 99.63 (C3), 79.06 (C5’iso), 61.21, 61.16, 56.30 (3CH3), 43.70 (–NCH2), 40.72 (C4’iso). HRMS (m/z) [C23H21BrN2O7+H]+: Mass calculated for: 517.0605, Mass found 517.0599.

-

e)

2-(((3-(4-bromophenyl)-4,5-dihydroisoxazol-5-yl)methyl)amcheno)-4-oxo-4H-chromene-3-carbaldehyde 5e.

Solid white, yield (64%), m.p = 208 °C, 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz δ in ppm): 10.86 (t, NH, J = 4.8 Hz), 10.22 (s, CHO), 8.22 (dd, Ar–H, J = 7.8, 1.68 Hz), 7.63 (tt, Ar–H, J = 13.2, 6.3 Hz), 7.52–7.56 (m, 4Ar-H), 7.41 (t, Ar–H, J = 7.44 Hz), 7.29 (d, Ar–H, J = 8.34 Hz), 5.05 (six, H5’), 3.84–6.86 (m, –NCH2), 3.16–3.54 (dd, 2H4’iso, J = 16.68, 10.56–16.68, 6.72 Hz). 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz δ in ppm): 189.73 (CHO), 175.65 (C=O), 164.82 (C2), 155.59, 153.24 (C3’), 133.80, 132.14, 128.21, 127.74, 126.44, 125.95, 124.95, 116.58, 99.61 (C3), 78.74 (C5’iso), 43.76 (–NCH2), 38.06 (C4’iso). HRMS (m/z) [C20H15BrN2O4+H]+: Mass calculated for: 429.0267, Mass found 429.0275.

Single–crystal XRD

The details of the crystal structure determination and refinement data are given in Tables S1. The crystal 5d was mounted on MiTeGen microMounts cryoloop and data were collected on a Bruker D8 VENTURE diffractometer using Mo-Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) from an IμS 3.0 microfocus source with multilayer optics, at 100 K. The structure was refined with anisotropic thermal parameters for non-H atoms. Hydrogen atoms were placed in fixed, idealized positions and refined with a riding model and a mutual isotropic thermal parameter. For structure solving and refinement the Bruker APEX4 Software Package was used79. The drawings were made using the Diamond program80. The CCDC reference number is 2,420,417. The supplementary crystallographic data for this article can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/.

Anti-inflammatory essay

To explore the in vitro anti-inflammatory effects of synthesized compounds 3 and 5(a-e), we used a lipoxygenase (5-LOX) inhibition assay, as described in our previous studies81,82. To achieve this, 0.05 ml of the investigated compounds (at different concentrations) and 0.05 ml of glycine max 5-LOX (100 U/ml) were combined with 0.5 ml of phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH = 9) and incubated at 25 °C for 8 min. Next, 0.05 ml linoleic acid (4.18 mM in ethanol) was added to the mixture, and the reaction was monitored for 3 min at 234 nm. Results have been expressed as IC50 ± SD based on three repeats, with Quercetin as the reference.

Antibacterial evaluation

Bacterial strains

Four bacterial strains were employed to assess the antibacterial efficacity of the conjugate, products, encompassing one Gram-positive bacterium, Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633, and three Gram-negative bacterial species: Klebsiella aerogenes ATCC 13,048, Escherichia coli ATCC 27,853, and Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi. These strains were selected based on their clinical relevance and representation of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. In this study, standard reference bacterial strains were selected to provide a broad-spectrum preliminary screening of the synthesized compounds in a reproducible and controlled manner. Although the clinical relevance of multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains is well recognized, their inclusion was not within the scope of this preliminary investigation. The use of MDR strains requires additional biosafety procedures and specific resistance profiling, which were beyond the logistical and technical constraints of this study. All bacterial strains used in this study were obtained from the Microbiology Laboratory at the Faculty of Sciences and Techniques in Fes, Morocco.

Disk diffusion test

Preliminary screening of the antibacterial activity of the six synthesized compounds 3 and 5(a-e) was carried out using the disk diffusion screening method, incorporating minor modifications as reported by El Bouzidi et al.83. Luria Broth (LB) agar medium was inoculated with the bacterial culture suspension. Next, sterile 6 mm filter paper discs, filled with 10 μL of the tested compounds were placed on the respective plates. Chloramphenicol (15 μg/disc) served as the bacteria’s reference drug (positive control). The inoculated plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, after which the inhibitory diameters were measured in millimeters. The results are expressed as mean ± SD, based on three independent replicates (n = 3). Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

The MIC of the synthesized compounds against the examined bacteria was determined using the microdilution technique in 96-well microplates, with slight modifications as previously mentioned84. Two-fold serial dilutions of 100 μL of the synthesized compounds (diluted in 1% DMSO) and the antibiotic (chloramphenicol) were prepared in individual wells in each row of the 96-well microplate. The microplates were then filled with 10 μL of microbial suspension adjusted to McFarland’s 0.5 standard and 95 μL of double-strength LB broth medium for bacteria. Incubation took place at 37 °C for 24 h. 40 μL of 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) at 0.2 μg/mL was added to each well to detect microbial growth. TTC is colorless in its oxidized form and turns red when reduced by microorganisms. MIC values were determined as the lowest concentrations at which no microbial growth was detected in the wells.

Minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) and MBC/MIC values

Following the completion of the MIC test, MBC assessments were conducted as previously described82. Briefly, 50 μL samples from each MIC well were plated onto Mueller–Hinton agar and incubated at 35 °C for 24 h. After incubation, plates were examined for bacterial growth. The MBC was identified as the lowest MIC with no observable growth. The MBC/MIC ratio was also calculated to classify the compounds as either bacteriostatic or bactericidal85.

In silico studies

The synthesized compounds with notable anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties were examined through in silico investigations, including molecular docking processes towards various relevant proteins and the prediction of physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties associated with Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADME-Tox). In the initial phase, the physicochemical and pharmacokinetic characteristics of ADME-Tox were estimated following Lipinski’s rules of five86,87, with the aid of online Pkcsm and Swissadme servers88,89. Next, molecular docking simulations, widely employed in the drug discovery90,91, were applied to the ligands synthesized in complex with the bacterial proteins of E. coli (6F86.pdb)48,92,93, B. subtilis (6CGQ.pdb)94, S. typhimurium (2YM9.pdb)95, and K. aerogenes (1FWE.pdb)96, as well as the Lipoxygenase (5-LOX) enzyme (1N8Q.pdb)81. The 3D structures of each receptor protein were converted from PDB to PDBQT format using standard protocols97,98. This process involved removing water molecules (H2O) and all other co-crystallized ligands and adding Gasteiger charges90,91. The candidate ligands were then docked to the active sites of the targeted proteins using Autodock 1.5.6 software99. Finally, the protein–ligand interactions obtained were visualized via Discovery Studio 2021 (DS 2021) software100.

DFT study

All calculations were performed using Gaussian09 software package101. DFT optimized molecular structures with the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level of theory in the gas phase were performed. To further assess the effect of the solvent on the stability and reactivity of these compounds, single point energy calculations were performed in water using the SMD solvation model at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level of theory. The energies of the frontier molecular orbitals HOMO (Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital) and LUMO (Lower Unoccupied Molecular Orbital) were calculated. They were used to compute the global reactivity descriptors like Electron Affinity (EA), Ionization Potential (IP), chemical potential (μ), electronegativity (χ), hardness(η), softness (S) and electrophilicity index (ω). The Multiwfn102, paired with VMD software103, were used to plot the Non-Covalent Interactions (NCI) and Electron localized function (ELF).

Conclusion

To sum up, a new series of chromone-isoxazoline hybrids was successfully synthesized, characterized, and evaluated for their biological activites using both in vitro and in silico approaches. The 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction used enabled the efficient synthesis of the desired products in good yields, and the chemical structures as well as the regiochemistry of the synthesized compounds were properly established. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction was then used to establish the crystal structure of the compound studied, showing that it crystallizes in a monoclinic system (S.G: P21/c). The findings of the antibacterial screening tests showed that conjugates 5b, 5c, and 5d exhibited significant antibacterial efficacy compared to the reference antibiotic, chloramphenicol. Furthermore, certain hybrid compounds demonstrated a bactericidal effect against specific tested strains, as evidenced by the results of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) tests. Regarding anti-inflammatory activity, the assays revealed that the hybrid compounds displayed remarkable effectiveness against the lipoxygenase enzyme (5-LOX), with conjugate 5e emerging as the most potent, showing an IC₅₀ value of 0.951 ± 0.02 mg/mL. The in vitro experimental results were further supported by in silico studies, including ADMET predictions and molecular docking simulations conducted against target proteins. These docking studies revealed good binding affinity of the examined hybrids toward bacterial strain proteins (E. coli 6F86, B. subtilis 6CGQ, S. typhimurium 2YM9, and K. aerogenes 1FWE) as well as with the lipoxygenase enzyme (5-LOX) (1N8Q). ADMET analyses also suggested low toxicity, non-carcinogenicity, and favorable drug-like and bioavailability profiles. Quantum chemical calculations at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level of theory in both gas phase and water provided additional insight into the electronic and chemical structure of the studied compounds. However, some important limitations should be acknowledged. The biological evaluation was limited to standard laboratory bacterial strains; therefore, further studies involving multidrug-resistant clinical isolates are necessary to assess the full therapeutic potential of these compounds. Moreover, although the observed anti-inflammatory and antibacterial activities are promising, the potency of these hybrids needs to be further optimized to match or surpass that of conventional drugs. Additionally, the theoretical results from quantum calculations require experimental validation. Finally, comprehensive in vivo studies, including pharmacokinetic and toxicity assessments, will be essential before considering clinical applications. Altogether, despite these limitations, the combined experimental, theoretical, and in silico findings strongly suggest that chromone-isoxazoline hybrids are promising candidates for further development as potent and selective agents targeting both pathogenic bacteria and the lipoxygenase enzyme (5-LOX).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The rest of the data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Boshtam, M., Asgary, S., Kouhpayeh, S., Shariati, L. & Khanahmad, H. Aptamers against pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines: A review. Inflammation 40, 340–349 (2017).

Pahwa, R., Goyal, A. & Jialal, I. Chronic Inflammation (StatPearls Publishing, 2018).

Luo, Y. et al. Role of arachidonic acid lipoxygenase pathway in Asthma. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 158, 106609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2021.106609 (2022).

Broos, J. Y. et al. Arachidonic acid-derived lipid mediators in multiple sclerosis pathogenesis: Fueling or dampening disease progression?. J. Neuroinflammation 21(1), 1–20 (2024).

Rådmark, O. & Samuelsson, B. 5-Lipoxygenase: Mechanisms of regulation. J. Lipid Res. 50, S40–S45 (2009).

Rådmark, O., Werz, O., Steinhilber, D. & Samuelsson, B. 5-Lipoxygenase, a key enzyme for leukotriene biosynthesis in health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 1851, 331–339 (2015).

Meshram, D., Bhardwaj, K., Rathod, C., Mahady, G. B. & Soni, K. K. The Role of leukotrienes inhibitors in the management of chronic inflammatory diseases. Recent Pat. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Discov. 14, 15–31 (2020).

Yao, L., Liu, Q., Lei, Z. & Sun, T. Development and challenges of antimicrobial peptide delivery strategies in bacterial therapy: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 253, 126819 (2023).

Elalouf, A., Yaniv-Rosenfeld, A. & Maoz, H. Immune response against bacterial infection in organ transplant recipients. Transpl. Immunol. 86, 102102 (2024).

Prestinaci, F., Pezzotti, P. & Pantosti, A. Antimicrobial resistance: A global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog. Glob. Health 109, 309–318 (2015).

Salam, M. A. et al. Antimicrobial resistance: A growing serious threat for global public health. Healthc. 11, 1946 (2023).

Terreni, M., Taccani, M. & Pregnolato, M. New antibiotics for multidrug-resistant bacterial strains: Latest research developments and future perspectives. Molecules 26, 2671 (2021).

Bbosa, G. S., Mwebaza, N., Odda, J., Kyegombe, D. B. & Ntale, M. Antibiotics/antibacterial drug use, their marketing and promotion during the post-antibiotic golden age and their role in emergence of bacterial resistance. Health (Irvine. Calif). 6, 410–425 (2014).

World Health Organizationrganization. WHO bacterial priority pathogens list, 2024: Bacterial pathogens of public health importance, to guide research, development, and strategies to prevent and and control antimicrobial resistance (2024).

Sati, H. et al. The WHO bacterial priority pathogens list 2024: A prioritisation study to guide research, development, and public health strategies against antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(25)00118-5 (2025).

Rotella, D. P. Chapter four—heterocycles in drug discovery: Properties and preparation. in Applications of Heterocycles in the Design of Drugs and Agricultural Products (eds. Meanwell, N. A. & Lolli, M. L. B. T.-A. in H. C.) vol. 134, 149–183 (Academic Press, 2021).

Baranwal, J., Kushwaha, S., Singh, S. & Jyoti, A. A review on the synthesis and pharmacological activity of heterocyclic compounds. Curr. Phys. Chem. 13, 2–19 (2022).

Kumar, G. & Shankar, R. 2-Isoxazolines: A synthetic and medicinal overview. Chem. Med. Chem. 16, 430–447 (2021).

Sedenkova, K. N. et al. Bicyclic isoxazoline derivatives: Synthesis and evaluation of biological activity. Molecules 27, 3546 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of novel osthole-based isoxazoline derivatives as insecticide candidates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 70, 7921–7928 (2022).

Zhang, P. et al. Synthesis and biological activities of novel isoxazoline-linked pseudodisaccharide derivatives. Carbohydr. Res. 351, 7–16 (2012).

Kalaria, P. N., Satasia, S. P. & Raval, D. K. Synthesis, identification and in vitro biological evaluation of some novel 5-imidazopyrazole incorporated pyrazoline and isoxazoline derivatives. New J. Chem. 38, 2902–2910 (2014).

Di Valentin, C., Freccero, M., Gandolfi, R. & Rastelli, A. Concerted vs stepwise mechanism in 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of nitrone to ethene, cyclobutadiene, and benzocyclobutadiene. A computational study. J. Org. Chem. 65, 6112–6120 (2000).

K. T. No & 1988, undefined. Nitrile oxides, nitrones, and nitronates in organic synthesis: Novel strategies in synthesis. cir.nii.ac.jp (1988).

Gothelf, K. V. & Jørgensen, K. A. Asymmetric 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions. Chem. Rev. 98, 863–910 (1998).

Baer, H. H. et al. The Nitro Group in Organic Synthesis (John Wiley & Sons, 2003).

Pearson, W. H. & Stoy, P. Cycloadditions of nonstabilized 2-azaallyllithiums (2-azaallyl anions) and azomethine ylides with alkenes: [3+2] approaches to pyrrolidines and application to alkaloid total synthesis. Synlett 2003, 903–921 (2003).

Srivastava, S. et al. In search of new chemical entities with spermicidal and anti-HIV activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 7, 2607–2613 (1999).

Browder, C. Recent advances in intramolecular nitrile oxide cycloadditions in the synthesis of 2-isoxazolines. Curr. Org. Synth. 8, 628–644 (2011).

Rane, D. & Sibi, M. Recent advances in nitrile oxide cycloadditions. Synth. Isoxazolines. Curr. Org. Synth. 8, 616–627 (2011).

Dofe, V. S. et al. Ultrasound assisted synthesis of tetrazole based pyrazolines and isoxazolines as potent anticancer agents via inhibition of tubulin polymerization. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 30, 127592 (2020).

Yousif, O. A., Mahdi, M. F. & Raauf, A. M. R. Design, synthesis, preliminary pharmacological evaluation, molecular docking and ADME studies of some new pyrazoline, isoxazoline and pyrimidine derivatives bearing nabumetone moiety targeting cyclooxygenase enzyme. J. Contemp. Med. Sci. 5, 41–50 (2019).

Manthey, J. A. & Buslig, B. S. Flavonoids in the living system: An introduction. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 439, 1–7 (1998).

Mohadeszadeh, M. & Iranshahi, M. Recent advances in the catalytic one-pot synthesis of flavonoids and chromones. Mini-Revi. Med. Chem. 17, 1377–1397 (2017).

Sosnovskikh, V. Y. Synthesis and reactions of halogen-containing chromones. Russian Chem. Rev 72(6), 489–516 (2003).

Middleton, E., Kandaswami, C. & Theoharides, T. C. The effects of plant flavonoids on mammalian cells: Implications for inflammation, heart disease, and cancer. Pharmacol. Rev. 52(4), 673–751 (2000).

García, A. et al. Flavonoids as anti-inflammatory agents: Implications in cancer and cardiovascular disease. Inflamm. Res. 58, 537–552. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-009-0037-3 (2009).

Pick, A. et al. Structure–activity relationships of flavonoids as inhibitors of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 19, 2090–2102 (2011).

Amaral, S., Mira, L., Nogueira, J. M. F., da Silva, A. P. & Florêncio, M. H. Plant extracts with anti-inflammatory properties—A new approach for characterization of their bioactive compounds and establishment of structure–antioxidant activity. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 17, 1876–1883 (2009).

Gong, J. et al. Preparation of two sets of 5, 6, 7-trioxygenated dihydroflavonol derivatives as free radical scavengers and neuronal cell protectors to oxidative damage. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 17(9), 3414–3425 (2009).

Yu, D. et al. Anti-HIV agents. Part 55: y 3 0 R,4 0 R-Di-(O)-(À)-camphanoyl-2 0 ,2 0-dimethyldihydropyrano[2,3-f]chromone (DCP), a novel anti-HIV agent. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 13, 1575–1576 (2003).

Ghani, S. B. A. et al. Convenient one-pot synthesis of chromone derivatives and their antifungal and antibacterial evaluation. Synth. Commun. 43, 1549–1556 (2013).

Xing, T. et al. Synthesis, anti-inflammatory activity, and conformational relationship studies of chromone derivatives incorporating amide groups. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 96, 129539 (2023).

Gontijo, V. S. et al. Molecular hybridization as a tool in the design of multi-target directed drug candidates for neurodegenerative diseases. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 18, 348–407 (2019).

Sampath Kumar, H. M., Herrmann, L. & Tsogoeva, S. B. Structural hybridization as a facile approach to new drug candidates. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 30, 127514 (2020).

Rodríguez, P. N., Ghashghaei, O., Bagán, A., Escolano, C. & Lavilla, R. Heterocycle-based multicomponent reactions in drug discovery: From hit finding to rational design. Biomedicines 10, 1488 (2022).

Shi, Q. Q. et al. Cimitriteromone A-G, macromolecular triterpenoid-chromone hybrids from the rhizomes of Cimicifuga foetida. J. Org. Chem. 83, 10359–10369 (2018).

Bouzammit, R. et al. Synthesis, characterization, DFT mechanistic study, antibacterial activity, molecular modeling, and ADMET properties of novel chromone-isoxazole hybrids. J. Mol. Struct. 1314, 138770 (2024).

Harnisch, H. Chromon-3-carbaldehyde. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 765, 8–14 (1973).

Ibrahim, S. S., Allimony, H. A., Abdel-Halim, A. M. & Ibrahim, M. A. Synthesis and reactions of 8-allylchromone-3-carboxaldehyde. ARKIVOC 14, 28–38 (2009).

Kanzouai, Y. et al. Design, synthesis, in-vitro and in-silico studies of chromone-isoxazoline conjugates as anti-bacterial agents. J. Mol. Struct. 1293, 136205 (2023).

Chalkha, M. et al. Synthesis, characterization, DFT mechanistic study, antimicrobial activity, molecular modeling, and ADMET properties of novel pyrazole-isoxazoline hybrids. ACS Omega 7, 46731–46744 (2022).

Kallitsakis, M. G. et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel hybrid molecules containing purine, coumarin and isoxazoline or isoxazole moieties. Open Med. Chem. J. 11, 196 (2017).

Grundmann, C. & Richter, R. Nitrile oxides. X. an improved method for the preparation of nitrile oxides from aldoximes. J. Org. Chem. 33, 476–478 (1968).

Li, H. J. et al. Regioselective electrophilic aromatic bromination: Theoretical analysis and experimental verification. Molecules 19(3), 3401–3416 (2014).

Appa, R. M., Naidu, B. R., Lakshmidevi, J., Vantikommu, J. & Venkateswarlu, K. Added catalyst-free, versatile and environment beneficial bromination of (hetero)aromatics using NBS in WEPA. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1–7 (2019).

Talha, A. et al. Ultrasound-assisted one-pot three-component synthesis of new isoxazolines bearing sulfonamides and their evaluation against hematological malignancies. Ultrason. Sonochem. 78, 105748 (2021).

Rhazi, Y. et al. Novel quinazolinone-isoxazoline hybrids: Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, and DFT mechanistic study. Chem. 4, 969–982 (2022).

Talha, A. et al. Ultrasonics sonochemistry ultrasound-assisted one-pot three-component synthesis of new isoxazolines bearing sulfonamides and their evaluation against hematological malignancies. Ultrason. Sonochem. 78, 105748 (2021).

Lobo, M. M. et al. Synthesis and cytotoxic activity evaluation of some novel 1-(3-(aryl-4,5-dihydroisoxazol-5-yl)methyl)-4-trihalomethyl-1H-pyrimidin-2-ones in human cancer cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 101, 836–842 (2015).

Filali, I., Bouajila, J., Znati, M., Bousejra-El Garah, F. & Ben Jannet, H. Synthesis of new isoxazoline derivatives from harmine and evaluation of their anti-Alzheimer, anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory activities. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 30, 371–376 (2015).

Chalyk, B. A., Zginnyk, O., Khutorianskyi, A. V. & Mykhailiuk, P. K. Functionalization of alkenes with difluoromethyl nitrile oxide to access the difluoromethylated derivatives. Org. Lett. 26, 2888–2892 (2024).

Domenicano, A., Vaciago, A. & Coulson, C. A. Molecular geometry of substituted benzene derivatives. I. On the nature of the ring deformations induced by substitution. Struct. Sci. 31(1), 221–234 (1975).

Alvarez, S. A cartography of the van der Waals territories. Dalton Trans. 42(24), 8617–8636 (2013).

Srivastava, P. et al. Synthesis, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) inhibition activities, and molecular docking study of 7-substituted coumarin derivatives. Bioorganic Chem. 67, 130–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2016.06.004 (2016).

Lončarić, M. et al. Lipoxygenase inhibition activity of coumarin derivatives—QSAR and molecular docking study. Pharmaceuticals 13(7), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13070154 (2020).

Shrivastava, S. K. et al. Synthesis, evaluation and docking studies of some 4-thiazolone derivatives as effective lipoxygenase inhibitors. Chem. Pap. 72(11), 2769–2783 (2018).

Mittal, R., Sharma, S. & Kushwah, A. S. An overview of novel bioactive compounds with potent anti-inflammatory activity via dual COX-2 and 5-LOX enzyme inhibition. Curr. Bioact. Compd. 18(9), 4–21 (2022).

Zghab, I. et al. Regiospecific synthesis, antibacterial and anticoagulant activities of novel isoxazoline chromene derivatives. Arab. J. Chem. 10, S2651–S2658 (2017).

Ed-Dahmani, I. et al. Phytochemical, antioxidant activity, and toxicity of wild medicinal plant of melitotus albus extracts, in vitro and in silico approaches. ACS Omega 9, 9236–9246 (2024).

El Fadili, M. et al. An in-silico investigation based on molecular simulations of novel and potential brain-penetrant GluN2B NMDA receptor antagonists as anti-stroke therapeutic agents. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 42(12), 6174–6188. https://doi.org/10.1080/07391102.2023.2232024 (2024).

El Fadili, M. et al. In-silico investigations of novel tacrine derivatives potency against Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. African 23, e02048 (2024).

El Fadili, M. et al. 3D-QSAR, ADME-tox in silico prediction and molecular docking studies for modeling the analgesic activity against neuropathic pain of novel NR2B-selective NMDA receptor antagonists. Process. 10, 1462 (2022).

Kitchen, D. B., Decornez, H., Furr, J. R. & Bajorath, J. Docking and scoring in virtual screening for drug discovery: Methods and applications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3(11), 935–949 (2004).

Lionta, E., Spyrou, G., Vassilatis, D. & Cournia, Z. Structure-based virtual screening for drug discovery: Principles, applications and recent advances. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 14, 1923–1938 (2014).

Zhang, Y. et al. Investigations based on non-covalent interactions in 1-(4-chloromethylbenzoyl)-3-(4, 6-di-substituted pyrimidine-2-yl)thioureas: Synthesis, characterizations and quantum chemical calculations. J. Mol. Struct. 1169, 85–95 (2018).

Ugwu, D. I. et al. Synthesis, structure, Hirshfeld surface analysis, non-covalent interaction, and in silico studies of 4-hydroxy-1-[(4-nitrophenyl) sulfonyl] pyrrolidine-2-carboxyllic acid. J. Chem. Crystallogr. 53(3), 386–399 (2023).

Silvi, B. & Savin, A. Classification of chemical bonds based on topological analysis of electron localization functions. Nature 371(6499), 683–686 (1994).

Sheldrick, G. M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Cryst. Struct. Commun. C71, 3–8 (2015).

Diamond, R. DIAMOND—visual crystal structure information system. Cryst. Impact 1251, 53002 (2001).

El Hachlafi, N. et al. Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) mast essential oil as a promising source of bioactive compounds with antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and dermatoprotective properties: In vitro and in silico evidence. Heliyon 10, e23084 (2024).

El Hachlafi, N. et al. Antioxidant, volatile compounds; antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and dermatoprotective properties of cedrus atlantica (Endl.) manetti ex carriere essential oil: In vitro and in silico investigations. Mol. 28, 5913 (2023).

Elbouzidi, A. et al. Chemical profiling of volatile compounds of the essential oil of grey-leaved rockrose (Cistus albidus L.) and its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antifungal, and anticancer activity in vitro and in silico. Front. Chem. 12, 1334028 (2024).

Al-Mijalli, S. H. et al. Integrated analysis of antimicrobial, antioxidant, and phytochemical properties of Cinnamomum verum: A comprehensive In vitro and In silico study. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 110, 104700 (2023).

Mrabti, H. N. et al. Phytochemical profile, assessment of antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of essential oils of Artemisia herba-alba Asso., and Artemisia dracunculus L.: Experimental and computational approaches. J. Mol. Struct. 1294, 136479 (2023).

Lipinski, C. A., Lombardo, F., Dominy, B. W. & Feeney, P. J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 23, 3–25 (1997).

El Fadili, M. et al. In-silico screening based on molecular simulations of 3,4-disubstituted pyrrolidine sulfonamides as selective and competitive GlyT1 inhibitors. Arab. J. Chem. 16, 105105 (2023).

Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 42717 (2017).

Pires, D. E., Blundell, T. L. & Ascher, D. B. pkCSM: Predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. J. Med. Chem. 58(9), 4066–4072 (2015).

El Fadili, M. et al. QSAR, ADME-Tox, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations of novel selective glycine transporter type 1 inhibitors with memory enhancing properties. Heliyon 9, e13706 (2023).

Fadili, M. E. et al. QSAR, ADMET in silico pharmacokinetics, molecular docking and molecular dynamics studies of novel bicyclo (aryl methyl) benzamides as potent GlyT1 inhibitors for the treatment of schizophrenia. Pharmaceuticals 15, 670 (2022).

Nouioura, G. et al. Petroselinum crispum L., essential oil as promising source of bioactive compounds, antioxidant, antimicrobial activities: In vitro and in silico predictions. Heliyon 10, e29520 (2024).

Nouioura, G. et al. Coriandrum sativum L., essential oil as a promising source of bioactive compounds with GC/MS, antioxidant, antimicrobial activities: In vitro and in silico predictions. Front. Chem. 12, 1369745 (2024).

Al-Ghulikah, H. et al. Novel isoxazole linked 1,5- benzodiazepine derivatives: Design, synthesis, molecular docking and antimicrobial evaluation. J. Mol. Struct. 1272, 134235 (2023).

Ejaz, S. et al. Functionalized chitosan based nanotherapeutics to combat emerging antimicrobial resistance in bacterial pathogen. Mater. Today Commun. 37, 107050 (2023).

Anusionwu, C. G. et al. Ferrocene-bisphosphonates hybrid drug molecules: In vitro antibacterial and antifungal, in silico ADME, drug-likeness, and molecular docking studies. Results Chem. 7, 101278 (2024).

Jeddi, M. et al. Antimicrobial, antioxidant, α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities of a chemically characterized essential oil from Lavandula angustifolia Mill.: In vitro and in silico investigations. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 111, 104731 (2023).

Benkhaira, N. et al. Unveiling the phytochemical profile, in vitro bioactivities evaluation, in silico molecular docking and ADMET study of essential oil from Clinopodium nepeta grown in Middle Atlas of Morocco. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 54, 102923 (2023).

Morris, G. M. et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2785–2791 (2009).

BIOVIA Discovery Studio—BIOVIA—Dassault Systèmes®, (n.d.). https://www.3ds.com/products-services/biovia/products/molecular-modeling-simulation/biovia-discovery-studio/. Accessed October 22 (2023).

Sieffert, N. & Wipff, G. Uranyl extraction by N,N-dialkylamide ligands studied using static and dynamic DFT simulations. Dalt. Trans. 44, 2623–2638 (2015).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graphics 14(1), 33–38 (1996).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their profound gratitude to the "Cité de l’Innovation" staff members of the Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Fez, Morocco. The authors extend their appreciation to the Ongoing Research Funding program, (ORF-2025-628), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work.

Funding

This work is supported by the Ongoing Research Funding program, (ORF-2025-628), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.B: synthesized the compounds and drafted the manuscript. M.E.K and R.S: conducted the density functional theory (DFT) studies and contributed to writing the article. E.G and L.G.I: performed the spectroscopic analysis. A.M.P: performed the crystal structure study. N.E.H: was responsible for evaluating the biological activities of the compounds. M.E.F: carried out the molecular docking studies. G.A.H: supervised and guided the overall study. Y.K, M.C, and M.M.A: reviewed the manuscript and contributed to the preparation of the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bouzammit, R., El Hachlafi, N., El fadili, M. et al. Synthesis, crystal structure, DFT calculations, in-vitro and in-silico studies of novel chromone-isoxazoline conjugates as antibacterial and anti-inflammatory agents. Sci Rep 15, 31103 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11182-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11182-9