Abstract

Burnout is common among nurses and undermines their health, well-being and job performance. The purpose of this two-wave longitudinal study was to analyze the relationships between loneliness and three dimensions of burnout (i.e. exhaustion, cynicism and professional efficacy) in this professional group and to test whether these relationships are mediated by insomnia. A total of 520 nurses were assessed at two time points, T1 and T2, six months apart, with a set of self-reported questionnaires including the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale (DJGLS), the Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS) and the Maslach Burnout Inventory – General Survey (MBI-GS). Socio-demographic and work-related characteristics were also recorded. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to analyze the data. The findings indicate that loneliness was positively associated with cynicism and negatively with professional efficacy, with both direct and total effects being statistically significant. However, the direct effect of loneliness on exhaustion was not confirmed, while the total effect was significant. Insomnia emerged as a significant mediator in each of these relationships. The present study clearly demonstrates the significance of the subjective appraisal of social connections and sleep problems in the development of burnout syndrome among nurses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Job burnout has been one of the most extensively studied work-related outcomes of job stress over the past 50 years1. For instance, a search combining the terms “occupational stress” and “job burnout” in the EBSCOhost database (PsycINFO and PsycEXTRA; 17/06/2024) yields 13,252 results. Both researchers and practitioners show considerable interest in this phenomenon due to its potentially serious negative consequences–at both the individual level (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular diseases2,3) and the organizational level (e.g., absenteeism, employee turnover4,5).

Although scholars have not reached full consensus regarding the conceptualization of burnout, the classical approach defines it as a psychological syndrome that emerges as a prolonged response to chronic stressors on the job and is characterized by three key dimensions: exhaustion, cynicism, and lack of professional efficacy6. Exhaustion is a state of physical, emotional, and mental fatigue, leading to a sense of overload and a depletion of emotional and cognitive resources. Cynicism is a distant, indifferent, or negative attitude toward work, colleagues, or service recipients, often serving as a defense mechanism in response to emotional strain. Lack of professional efficacy denotes a reduced sense of competence, achievement, and effectiveness at work, typically accompanied by feelings of inadequacy and a diminished belief in one’s ability to successfully perform job-related tasks. Within this framework, job burnout is perceived as a consequence of prolonged stress caused by dysfunctional interactions between the individual and their organizational environment5, including “poor” interpersonal relationships with other members of the organization7,8.

Nurses are particularly vulnerable to experiencing burnout syndrome due to the high demands of their job and sustained exposure to occupational stress, which may compromise their health, well-being and work performance9,10,11,12. Meta-analyses indicate that the prevalence of burnout in this professional group may reach as high as 56%13,14, with particularly elevated levels observed during the COVID-19 pandemic15. Beyond its detrimental effects on nurses’ own health, burnout can also undermine patient health and safety. For instance, a meta-analysis of 85 studies found that nurse burnout is associated with decreased quality of care, increased medical errors, higher rates of hospital-acquired infections, more frequent patient falls, and lower patient satisfaction14. In the light of these findings, a better understanding of the causes and mechanisms underlying the development of burnout among nurses appears to be well justified.

A wide range of factors, both situational and individual, have been identified as affecting the prevalence and severity of burnout4,6,16. However, loneliness, i.e. perceived social isolation, is definitely one of the under-researched potential contributors to burnout among nurses17,18. Loneliness is increasingly recognized as a global public health concern19. Numerous studies showed that it has harmful effects on various mental and physical health outcomes and significantly increases the risk of premature mortality20,21,22,23,24,25,26. However, the role of loneliness in the workplace and its impact on workers and employers have thus far received relatively little attention from researchers. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Bryan et al.27 revealed that in various professions loneliness at work is associated with lower job performance, reduced job satisfaction, worse worker-manager relationships and elevated levels of burnout. The authors indicate, though, that the robustness of these findings remains questionable since most of the studies included were cross-sectional.

Another review by Wood et al.28 focused on the evidence for an association between loneliness and burnout in nurses. Nevertheless, although the primary intent of this review was to explore the concept of loneliness, the authors surprisingly found that this concept has hardly been studied among nurses in the context of burnout. Therefore, they used the social support construct as a proxy for loneliness. Their analyses revealed that lower social support predicted higher levels of burnout in nurses, with social support explaining about a third of the variance in burnout. It needs to be noted here that social support and loneliness are closely related yet distinct phenomena29,30,31,32. The main difference between the two lies in the fact that the notion of social support emphasizes the importance of help provided through social relationships, whereas the loneliness concept calls attention to the role of pleasurable companionship and intimacy29. In turn, two recent pieces of research by Wood et al.17,18 demonstrated that rates of loneliness and burnout among nurses are positively correlated, and highlighted the importance of social connectedness for improving nurse well-being. However, these studies were rather modest-scale, utilizing cross-sectional and qualitative data.

The literature reviewed above clearly shows that the empirical evidence for the role of loneliness in shaping the intensity of burnout in the nursing profession is scarce and weak. In order to be able to work out successful interventions targeting burnout in nurses, these drawbacks have to be addressed by performing longitudinal studies on substantial samples, exploring links between appropriately measured loneliness and burnout. Although the exact mechanism through which loneliness negatively affects health and well-being is not well understood, it is believed to act via both direct and indirect pathways. One of the most commonly acknowledged mediators of the impact of loneliness on mental and physical health is sleep impairment, which impedes its restorative functions20,21,22,23,24,25,26. A systematic review and meta-analysis aiming to synthesize the research on the relationship between loneliness and sleep showed a medium-sized correlation between loneliness and sleep disturbance (defined as sleep quality and insomnia symptoms) across a wide array of measures and samples33. In this review loneliness was also found to be associated with inadequacy of sleep and dissatisfaction with it, but not sleep duration. There is, then, sufficient evidence to consider loneliness as a potential risk factor for sleep problems. However, the directionality of this relationships has not yet been fully established and it is possible that feelings of social isolation and sleep impairments mutually reinforce each other23,33,34.

There is also a considerable body of evidence demonstrating the association of sleep disturbances with burnout among healthcare professionals35,36,37,38. Nurses typically work shifts and extended working hours, which may alter their circadian rhythm and sometimes lead to the abuse of caffeine and benzodiazepines39,40. Such functioning may result in changes in sleep architecture, reduction in the amount and deterioration of sleep quality41 and, in the long term, insomnia36. Indeed, Huang and Zhao42 reported that in the initial phase of the COVID-19 epidemic, the problem of insomnia was the most serious among healthcare workers compared to other professional groups. Insomnia weakens the employee’s physical and mental strength36, and also drains the personal resources needed to cope with stress43, which may intensify the symptoms of physical and mental fatigue and consequently lead to burnout44.

An additional problem may be difficulties in recovery45, caused by irregular working patterns and variable sleep–wake cycles. According to the effort-recovery model46, in order to maintain “good” health at work, an employee should balance the time devoted to work and rest47. Therefore, after intense work-related effort, there should be a break for regeneration, e.g. sleep. However, full recovery can occur only when no job-related demands arise during non-work time45,46. Insufficient time for regeneration (especially after a heavy or long-term workload) may cause employees to incur greater costs associated with coping with new demands (e.g. the need to put more effort into work or greater fatigue) and become more susceptible to stress, which may result in burnout48. In this context, it should be emphasized, however, that despite the fact that both the theoretical rationale and empirical evidence indicate that impaired sleep may be a factor contributing to the development of burnout among healthcare professionals, most of the studies investigating this issue use a cross-sectional design and preclude the disentangling of the possibly complex relations between the two phenomena.

Thus, in this research, our main aim is to shed more light on the relationships between loneliness, insomnia and burnout among nurses. In view of the relevant literature, we postulate that insomnia may act as mediator in the relationship between loneliness and dimensions of burnout and we test this assumption in a two-wave longitudinal study including a relatively large sample of nurses. More specifically, we hypothesize that:

H1

Higher loneliness will be linked over time to higher exhaustion (H1a), higher cynicism (H1b), and lower professional efficacy (H1c);

H2

Insomnia will mediate the relationship between loneliness and burnout, such that higher loneliness will lead to higher insomnia, which in turn will increase exhaustion (H2a), increase cynicism (H2b), and reduce professional efficacy (H2c).

Methods

Participants

The participants were 520 nurses, 480 (92.3%) women and 40 (7.7%) men. Respondents’ ages ranged from 26 to 78 years (M = 51.21; SD = 10.15) and seniority from less than one year to 53 years (M = 25.26; SD = 11.77). Other socio-demographic and job-related characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 1.

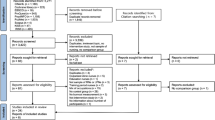

Procedures

The ethical approval for this project was granted by the Bioethical Committee of the Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology in Warsaw (21/2020). Recruitment took place in two stages. In the first stage, a request was sent to people managing the nursing departments (Nursing Directors or Chief Nurses) of ten hospitals in the Masovian Province in Poland. After an initial interview explaining the objectives of the study, seven hospitals joined the project. Consent to conduct a survey among nurses employed in these facilities was obtained after submitting an official letter to the directors. The further course of recruitment was agreed with the managing nurses in accordance with the assumptions of the project. Informed consent was obtained from all individuals taking part in the study. Participants were assessed at two time points, T1 and T2, six months apart. The first part of the study was carried out between May and July 2021.

Measures

Professional burnout was assessed with the Maslach Burnout Inventory–General Survey (MBI-GS), a self-report tool developed by Schaufeli et al.49 and validated for use in research in the Polish language by Chirkowska-Smolak and Kleka50. The questionnaire comprises sixteen items, scored from 0 to 6, divided into three subscales: exhaustion, cynicism (understood as a feeling of indifference towards one’s job) and sense of professional efficacy. Each subscale is interpreted separately. High indices of exhaustion and cynicism and low professional efficacy indicate burnout syndrome. The McDonald’s omega values for the individual subscales at each measurement point were as follows: Exhaustion T1 = 0.909 [95% CI 0.894–0.921]; Exhaustion T2 = 0.893 [95% CI 0.872–0.907]; Cynicism T1 = 0.836 [95% CI 0.808–0.860]; Cynicism T2 = 0.810 [95% CI 0.773–0.841]; Professional Efficacy T1 = 0.786 [95% CI 0.749–0.817]; Professional Efficacy T2 = 0.826 [95% CI 0.787–0.859].

Loneliness was measured by means of the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale (DJGLS) devised by De Jong Gierveld and Kamphuis51. The Polish version was validated by Grygiel et al.52 The scale consists of 11 items, to which interviewees respond by using a five-point scale ranging from 1 (yes!) to 5 (no!). It can be used to assess both the overall level of loneliness and its two dimensions: the emotional (6 items) and the social (5 items). After recoding the items that refer to the emotional aspects of loneliness, a higher total score denotes a more severe global sense of loneliness. McDonald’s omega: T1 = 0.914 [95% CI 0.897–0.924]; T2 = 0.919 [95% CI 0.906–0.929].

The Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS) was used. The instrument was elaborated by Soldatos et al.53 and validated in Polish by Fornal-Pawłowska et al.54 This eight-item self-report questionnaire is grounded in the ICD-10 criteria and assesses symptoms of insomnia, such as difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep or poor quality of sleep, and their impact on daily functioning. To meet the criteria, symptoms must occur at least three times a week and persist for at least one month. Each item is rated on a scale from 0 (no problem at all) to 3 (very serious problem), with higher total score indicating greater insomnia severity. McDonald’s omega: T1 = 0.852 [95% CI 0.825–0.874]; T2 = 0.860 [95% CI 0.839–0.879].

Data regarding socio-demographic and work-related characteristics of the participants were collected using a questionnaire prepared specifically for the purpose of this project.

Statistical analyses

There were no missing data in the dataset. Outliers were assessed via boxplots and casewise Mahalanobis distance (p < 0.001 threshold), with no observations exceeding the critical value. Preliminary analyses included descriptive statistics for the mean scores of the instruments used and their correlations and group differences. To examine group differences, non-parametric tests were conducted due to unequal group sizes. The Mann–Whitney U test was used for two-group comparisons, and the Kruskal–Wallis test for comparisons involving more than two groups. Effect sizes were also calculated: Glass’s rank-biserial correlation (rg) for the Mann–Whitney U test and epsilon squared (ε2) for the Kruskal–Wallis test. The reliability of the scales and subscales was also assessed. Given that Cronbach’s alpha (α) has been criticized for underestimating reliability when items are not tau-equivalent55,56,57, we opted to use McDonald’s omega (ω) coefficient, computed for each scale and subscale under a single-factor model56. Reliability was considered acceptable if the coefficient reached at least 0.7055. Estimates were supplemented with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) calculated using bootstrapping with 1000 samples. The results are reported in Section "Measures". Additionally, we examined the potential impact of common method bias using Harman’s single-factor test, with a variance explained by a single factor exceeding 50% indicating the presence of common method bias58.

The main analyses were conducted using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), with observed variables being items of scales that served as indicators of latent variables. We employed the ULSMV estimator (Unweighted Least Squares Mean and Variance Adjusted), which, as demonstrated by Rhemtulla et al.59, is appropriate for medium-sized samples when variables have four response categories (AIS), and remains acceptable for five (DJGLS) and seven categories (MBI-GS). All latent and observed variables were standardized. The structural model was estimated in R, version 4.2.360 using the lavaan package61. Model fit was evaluated on the basis of the following criteria: Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) values above 0.95, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) below 0.05, p-value for Close Fit (Pclose) above 0.05, and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) below 0.0862,63. Convergent validity was assessed using Average Variance Extracted (AVE)64, with a threshold of 0.50, while discriminant validity was evaluated using the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations, which should not exceed 0.8565,66. Age and seniority were tested as covariates in preliminary SEM runs; however, their inclusion did not materially change the path coefficients, so they were not retained in the final model. Path coefficients between latent variables were examined to test the hypotheses. To verify mediation effects, indirect effect estimates were computed67,68. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, with CI not encompassing 0.

We assumed a statistical power of 0.80 and an effect size of 0.20, based on findings from previous studies involving our variables28,69,70,71,72,73. Using these assumptions, we calculated that a minimum sample size of 376 was required to detect the effect in our model74,75. Additionally, given our model’s high degrees of freedom, the RMSEA index achieves a power of 0.80 for detecting poor fit with a sample size of n = 6776,77.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Before conducting the analyses the data were pre-checked. No missing data were observed, and no significant outliers were identified. Descriptive statistics, reliability, and correlation analysis results are presented in Table 2. The findings indicated that each scale demonstrated good internal consistency. Correlation analysis revealed a positive association between loneliness and insomnia, exhaustion, and cynicism, as well as a negative correlation with professional efficacy. Furthermore, insomnia was positively correlated with exhaustion and cynicism, and negatively correlated with professional efficacy. These findings provide the foundation for testing more advanced hypotheses.

No significant differences were observed between women and men regarding loneliness (U = 8600; p = 0.273; rg = 0.104), insomnia (U = 9490; p = 0.904; rg = 0.012), exhaustion (U = 9084; p = 0.572; rg = 0.054), and cynicism (U = 8977; p = 0.494; rg = 0.065). The difference in professional efficacy was statistically significant (U = 7579; p < 0.05; rg = 0.211), with men rating their professional efficacy higher than women (M = 4.38; Me = 4.58; SD = 0.97 vs. M = 4.02; Me = 4.00; SD = 1.02). No differences were noted between individuals with different marital statuses regarding loneliness (H = 3.46; df = 4; p = 0.485; ε2 = 0.007), exhaustion (H = 4.20; df = 4; p = 0.380; ε2 = 0.008) and cynicism (H = 5.78; df = 4; p = 0.216; ε2 = 0.011). However, for insomnia (H = 14.16; df = 4; p < 0.01; ε2 = 0.027) and professional efficacy (H = 9.94; df = 4; p < 0.05; ε2 = 0.019) the result of the H-Kruskal–Wallis test was statistically significant, but the effect sizes were small, and the results of all pairwise comparisons using the Dwass-Steel-Critchlow-Fligner method were not statistically significant. Similarly, no differences were found between nurses employed in different workplaces (loneliness: H = 9.63; df = 9; p = 0.381; ε2 = 0.019; insomnia: H = 14.06; df = 9; p = 0.120; ε2 = 0.027; exhaustion: H = 13.99; df = 9; p = 0.123; ε2 = 0.027; cynicism: H = 8.87; df = 9; p = 0.450; ε2 = 0.017; professional efficacy: H = 6.36; df = 9; p = 0.703; ε2 = 0.012).

Harman’s single factor test showed that a single factor explained 24.49% of the variance in the items from all scales. This suggests that our results are not affected by common method bias.

Structural equation modeling

In the next step of the analyses, we developed a structural model according to the effects postulated in the hypotheses. The fit statistics are presented in Table 3.

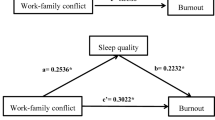

The results confirm the good fit of the model. Therefore, no covariances between observed variables were included in the model. AVE values ranged from 0.502 for loneliness to 0.656 for exhaustion. Additionally, the HTMT values ranged from 0.132 for the relationship between exhaustion and professional efficacy to 0.760 for the relationship between cynicism and exhaustion. Thus, it can be concluded that there are no issues with the validity of the model. The structural model is presented in Fig. 1.

Hypothesis 1 examined the relationships between loneliness and burnout. As shown in Table 4, Hypothesis 1a was not confirmed for the direct effect but was supported for the total effect. The effect of loneliness on cynicism (positive) and professional efficacy (negative) was statistically significant for both the direct paths and total effects, supporting H1b and H1c. Furthermore, the results indicate that loneliness was significantly associated with insomnia, which, in turn, was significantly related to exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy. The indirect effect of loneliness on exhaustion via insomnia, as hypothesized in H2a, was confirmed. These findings suggest that the effect of loneliness on exhaustion was fully mediated by insomnia. Additionally, the indirect path from loneliness to cynicism through insomnia was statistically significant, confirming H2b. Similarly, the mediating role of insomnia in the relationship between loneliness and professional efficacy was confirmed, supporting H2c. However, while the mediation was full in the case of exhaustion, for cynicism and professional efficacy, it was only partial.

Discussion

Designing effective interventions through which to prevent or reduce burnout syndrome among nurses requires a good understanding of the factors underlying its development in this professional group and disentangling their interrelationships. Much is already known about the antecedents and possible causes of burnout4,6,16. However, to the best of our knowledge the present study is the first to explore the prospective associations between loneliness and burnout and to test the mediating role of insomnia in this relationship. We used a relatively large sample of Polish nurses and advanced statistical methods to verify our hypothesized model. The results support the notion that loneliness contributes to the intensification of burnout among nurses, with insomnia fully mediating the relationship between loneliness and exhaustion, and partially mediating its effects on cynicism and professional efficacy.

In accordance with our predictions, more severe loneliness turned out to be directly related to higher cynicism and lower professional efficacy. Instead, and contrary to our expectations, the direct effect of loneliness on exhaustion was not significant. As for the positive relationship between loneliness and cynicism, it may be the case that loneliness predisposes a person to having a detached attitude towards clients/patients and the work environment, since lonely people suffer from biased social information processing. For example, it has been demonstrated that loneliness is associated with increased attention being paid to socially threatening stimuli, negative and hostile intent attributions, expectations of rejection or a tendency to evaluate characteristics and behaviors of others negatively78. These distorted social cognitions may elicit unfavorable reactions from others, thus reinforcing the feelings of loneliness and cynicism. Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that insomnia is also associated with impaired cognitive performance, both generally and across multiple specific cognitive domains79. Moreover, sleep has far-reaching effects on social processes from basic social cognition to complicated social interactions80. This suggests that loneliness and insomnia may interact in their impact on cynicism in a very complex way, which merits further investigation. As for professional efficacy, it seems plausible to assume that for nurses who feel lonely it may be particularly challenging to maintain a satisfactory level of professional efficacy in a job that, by its very nature, demands frequent, intensive and often intimate contact with others. Furthermore, loneliness has been found to be related to negative self-evaluations and diminished self-efficacy78.

However, all three intermediate effects tested in the model were confirmed. The mechanism through which loneliness impairs sleep is probably complex. One may speculate that loneliness leads to sleep disturbances both directly, by activating the stress response and causing physiological arousal, and indirectly, by negatively affecting health practices and health-promoting behaviors (e.g., alcohol and drug use, less exercise, less relaxation, poor nutrition and obesity)21,23.

The associations between insomnia and the three components of job burnout are not uniform. In the case of exhaustion, a complete mediation effect can be observed — when insomnia is introduced as a mediator, the direct relationship between predictor and exhaustion becomes non-significant. This effect stems from the particularly strong association between insomnia and exhaustion. These findings are consistent with theoretical expectations as well as with prior studies35,36,37,38. For instance, a meta-analysis of 12 studies examining the relationship between insomnia and burnout among nurses reported a mean correlation coefficient of r = 0.39 between overall burnout levels and sleep disturbances36. Other studies involving this professional group have similarly demonstrated that insomnia is associated with two core components of occupational burnout–exhaustion (r = 0.30) and depersonalization (r = 0.26). Furthermore, it has been observed that insomnia increases the likelihood of experiencing job burnout by more than 2.5 times.

Several mechanisms may underlie the relationship between insomnia and exhaustion. First, sleep disturbances can induce an excessive activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in elevated cortisol levels81,82. Chronic overactivation of the stress response system may, over time, contribute to the development of exhaustion6,48. Moreover, sleep disturbances can impair emotional self-regulation83,84. Deficits in emotion regulation heighten vulnerability to stress and increase the likelihood of responding to challenging work situations with negative emotions — a process that itself may be emotionally depleting85,86. Finally, chronic insomnia progressively depletes employees’ personal resources and disrupts the recovery processes required to restore resources eroded by stress43. An insufficiency of resources with which to cope with which job demands directly contributes to the experience of exhaustion5.

Significant mediating effects of insomnia were also observed for the other two components of job burnout, namely depersonalization and low professional efficacy. The weakest indirect effect was found for the third component–low professional efficacy. This relatively weak effect was primarily due to the low, albeit statistically significant, relationship between insomnia and low professional efficacy. In this case, a considerable proportion of the total effect was explained by the direct effect. It is possible that in professions with a strong social mission–such as nursing–where the core job tasks involve establishing and maintaining close emotional relationships with others, the sense of high professional competence is strongly linked to the ability to build and sustain these interpersonal bonds. Consequently, a sense of social isolation at work may undermine professional efficacy.

Theoretical and practical implications

The present study offers several important theoretical and practical contributions. First, the results reveal alternative mechanisms underlying the development of job burnout. The widely recognized and extensively studied Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) theory87 identifies an imbalance between job demands present in the work environment and the resources available to employees to cope with these demands as the primary driver of burnout. However, the findings of the current study suggest that the onset of burnout can also be triggered by feelings of loneliness. Although loneliness is not directly associated with all components of burnout — including exhaustion, which is considered the core element of this construct — it leads to increased insomnia, which disrupts recovery processes45 and, consequently, contributes to resource depletion — a central feature of job burnout87.

These findings are particularly relevant in the context of nurses’ occupational functioning. Nursing is typically shift-based work, often performed at irregular hours, including night shifts. Such irregular schedules disrupt the sleep–wake cycle, contributing to sleep disturbances, chronic fatigue, and impaired recovery88,89. Long-term disruption of biological rhythms has been linked to difficulties in maintaining mental health, including an elevated risk of burnout90,91. The present results are also relevant to the current situation of Polish nurses in the labor market, in which working conditions are extremely challenging. According to the OECD report Health at a Glance: Europe 2020, Poland has one of the lowest nurse-to-population ratios in Europe, with only 5.1 nurses per 1000 residents. This figure is significantly below the EU average of 8.2 and far behind Norway, which leads with 17.7 nurses per 1,000 residents. Projections from the Supreme Chamber of Nurses and Midwives (2017) suggest that by 2030, this ratio could decline further to just 3.81. Another cause for concern is the relatively high average age of Polish nurses, which currently stands at 52.2 years. Nearly 52% of all nurses are over the age of 51, while those under 30 account for only 5.5% of the workforce. This aging workforce is largely the result of the emigration of younger, highly qualified Polish nurses to Western European countries, coupled with declining interest in nursing programs in Poland in recent years.

Our findings point to loneliness and insomnia as potential targets of interventions aiming to mitigate burnout and its harmful sequelae in the nursing profession. Researchers identify four main strategies of loneliness reduction interventions: improving social skills, enhancing social support, increasing opportunities for social contact, and addressing maladaptive social cognition92. Employers should be aware of the significance of social connectedness for nurses’ well-being and make efforts to adapt these interventions to the occupational health setting and to build a supportive work environment17,18,27,28. In turn, for the amelioration of sleep problems, Membrive-Jiménez et al.36 in their review of the literature found that both psychological interventions and modifications in nurses’ working conditions may be beneficial. The former may include, for example, a rehabilitation program based on psychoeducation for stress management or a personal self-care program based on changing night-time habits and stress management. Among the latter, the authors recommend developing turnicity strategies that limit alterations in circadian rhythm, using warmer lights in hospital units during night shifts and, where possible, elimination of the fixed night shift.

Limitations

Several methodological limitations of this study need to be mentioned. First, the follow-up was relatively short. Studies with an observation period longer than half a year would provide stronger evidence supporting the hypothesized theoretical model. Our data do not allow for the inference of definite conclusions about the direction of the relationships observed or causality. Furthermore, because the sample was restricted to urban hospitals in the Masovian Province, caution is needed when extending results to nurses in rural regions or other countries. Next, all the components of our model were measured using self-report instruments. It cannot be ruled out either that some unmeasured variables may have influenced the strength of the associations between loneliness, insomnia and the dimensions of burnout.

Another limitation concerns the number of measurement points in the present study. When testing mediation models involving at least three constructs, it is recommended to conduct at least three measurement waves, ensuring that all study variables are assessed at each time point93. This approach allows for cross-lagged analyses, which enable the examination of relationships between variables over time while controlling for their prior values. In the current study, only two measurement waves were conducted, necessitating a decision regarding which mediator value (from the first or second measurement) should be included in the model tested. We selected the insomnia (as well as loneliness) values from the first measurement, as our primary interest was in examining the short-term relationship between loneliness and insomnia, as well as the delayed effects of these variables on job burnout—a process that develops gradually over an extended period.

Conclusions

The present study clearly demonstrates the significance of the subjective appraisal of social connections in the development of burnout syndrome among nurses. This indicates that alleviating nurses’ loneliness through targeted interventions is one of the promising routes to improving their well-being. No less important is counteracting insomnia in the nursing profession, which emerged as a mediator of the effects of loneliness on burnout. Managers should take it into account and adapt nurses’ working conditions so as to minimize the risk of sleep problems related to the performance of this stressful and demanding job.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Dreison, K. C. et al. Job burnout in mental health providers: A meta-analysis of 35 years of intervention research. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 23, 18–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000047 (2018).

Melamed, S., Shirom, A., Toker, S., Berliner, S. & Shapira, I. Burnout and risk of cardiovascular disease: Evidence, possible causal paths, and promising research directions. Psychol. Bull. 132, 327–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.3.327 (2006).

Salvagioni, D. A. J. et al. Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS ONE 12, e0185781. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185781 (2017).

Schaufeli, W. & Enzmann, D. The Burnout Companion to Study and Practice: A Critical Analysis. (Taylor & Francis, London, 1998).

Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. & Maslach, C. Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Dev. Int. 14, 204–220. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430910966406 (2009).

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B. & Leiter, M. P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397 (2001).

Maslach, C. & Leiter, M. P. Burnout. In Stress Consequences: Mental, Neuropsychological and Socioeconomic (ed. Fink, G.) 726–729 (Elsevier Academic Press, London, 2010).

Aronsson, G. et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health 17, 264. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4153-7 (2017).

Li, H., Cheng, B. & Zhu, H. P. Quantification of burnout in emergency nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 39, 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2017.12.005 (2018).

Buckley, L., Berta, W., Cleverley, K., Medeiros, C. & Widger, K. What is known about paediatric nurse burnout: A scoping review. Hum. Resour. Health 18, 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-0451-8 (2020).

Dall’Ora, C., Ball, J., Reinius, M. & Griffiths, P. Burnout in nursing: A theoretical review. Hum. Resour. Health 18, 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-00469-9 (2020).

Chen, C. & Meier, S. T. Burnout and depression in nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 124, 104099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104099 (2021).

Hall, L. H., Johnson, J., Watt, I., Tsipa, A. & O’Connor, D. B. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 11, e0159015. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159015 (2016).

Li, L. Z. et al. Nurse burnout and patient safety, satisfaction, and quality of care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2443059. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.43059 (2024).

Ghahramani, S. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of burnout among healthcare workers during COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 12, 758849. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.758849 (2021).

Demerouti, E. Burnout: A comprehensive review. Zeitschrift für Arbeitswissenschaft 78, 492–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41449-024-00452-3 (2024).

Wood, R. E. et al. A mixed-methods exploration of nurse loneliness and burnout during COVID-19. Appl. Nurs. Res. 73, 151716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2023.151716 (2023).

Wood, R. E., Paulus, A. B. & Elswick, R. K. M. Exploring loneliness and burnout in nephrology nurses: A mixed-methods analysis. Nephrol. Nurs. J. 51, 433–442. https://doi.org/10.37526/1526-744X.2024.51.5.433 (2024).

Cacioppo, J. T. & Cacioppo, S. The growing problem of loneliness. Lancet 391, 426. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30142-9 (2018).

Cacioppo, J. T. et al. Loneliness and health: Potential mechanisms. Psychosom. Med. 64, 407–417. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200205000-00005 (2002).

Heinrich, L. M. & Gullone, E. The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 26, 695–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002 (2006).

Cacioppo, J. T. & Hawkley, L. C. Loneliness. In Handbook of Individual Differences in Social Behaviour (eds. Leary, M. R. & Hoyle, R. H.) 227–240 (Guilford Press, New York, 2009).

Hawkley, L. C. & Cacioppo, J. T. Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 40, 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8 (2010).

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T. & Stepheson, D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10, 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352 (2015).

Park, C. et al. The effect of loneliness on distinct health outcomes: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 294, 113514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113514 (2020).

Hawkley, L. C. Loneliness and health. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 8, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-022-00355-9 (2022).

Bryan, B. T. et al. Loneliness in the workplace: A mixed-method systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup. Med. (Lond) 73, 557–567. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqad138 (2023).

Wood, R. E., Brown, R. E. & Kinser, P. A. The connection between loneliness and burnout in nurses: An integrative review. Appl. Nurs. Res. 66, 151609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2022.151609 (2022).

Rook, K. S. The functions of social bonds: Perspectives from research on social support, loneliness and social isolation. In Social Support: Theory, Research and Applications (eds. Sarason, I. G. & Sarason, B. R.) 243–267 (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Dordrecht, 1985).

Newcomb, M. D. & Bentler, P. M. Loneliness and social support: A confirmatory hierarchical analysis. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 12, 520–535. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167286124015 (1986).

Penninx, B. W. J. H. et al. Social network, social support, and loneliness in older persons with different chronic diseases. J. Aging Health 11, 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/089826439901100202 (1999).

Tomaka, J., Thompson, S. & Palacios, R. The relations of social isolation, loneliness, and social support to disease outcomes among the elderly. J. Aging Health 18, 359–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264305280993 (2006).

Griffin, S. C., Williams, A. B., Ravyts, S. G., Mladen, S. N. & Rybarczyk, B. D. Loneliness and sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Open 7, 2055102920913235. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102920913235 (2020).

Griffin, S. C. et al. Reciprocal effects between loneliness and sleep disturbance in older Americans. J. Aging Health 32, 1156–1164. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264319894486 (2020).

Stewart, N. H. & Arora, V. M. The impact of sleep and circadian disorders on physician burnout. Chest 156, 1022–1030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.07.008 (2019).

Membrive-Jiménez, M. J. et al. Relation between burnout and sleep problems in nurses: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Healthcare (Basel) 10, 954. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10050954 (2022).

Shechter, A. et al. Sleep disturbance and burnout in emergency department health care workers. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2341910. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.41910 (2023).

Saintila, J., Soriano-Moreno, A. N., Ramos-Vera, C., Oblitas-Guerrero, S. M. & Calizaya-Milla, Y. E. Association between sleep duration and burnout in healthcare professionals: A cross-sectional survey. Front. Public Health 11, 1268164. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1268164 (2024).

Hsieh, M. L. et al. Sleep disorder in Taiwanese nurses: A random sample survey. Nurs. Health Sci. 13, 468–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00641.x (2011).

Cheng, H., Liu, G., Yang, J., Wang, Q. & Yang, H. Shift work disorder, mental health and burnout among nurses: A cross-sectional study. Nurs. Open 10, 2611–2620. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.1521 (2023).

Geiger-Brown, J. et al. Sleep, sleepiness, fatigue, and performance of 12-hour-shift nurses. Chronobiol. Int. 29, 211–219. https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2011.645752 (2012).

Huang, Y. & Zhao, N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 288, 112954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954 (2020).

Hobfoll, S. E. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 6, 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307 (2002).

Armon, G., Shirom, A., Shapira, I. & Melamed, S. On the nature of burnout-insomnia relationships: A prospective study of employed adults. J. Psychosom. Res. 65, 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.01.012 (2008).

Sonnentag, S., Cheng, B. H. & Parker, S. L. Recovery from work: Advancing the field toward the future. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 9, 33–60. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-091355 (2022).

Meijman, T. F. & Mulder, G. Psychological aspects of workload. In Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology, Volume 2: Work Psychology, Second Edition (eds. Drenth, P. J. D., Thierry, H. & de Wolff, C. J.) 5–33 (Psychology Press Ltd, Hove, 1998).

Geurts, S. A. & Sonnentag, S. Recovery as an explanatory mechanism in the relation between acute stress reactions and chronic health impairment. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 32, 482–492. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.1053 (2006).

McEwen, B. Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. In Molecular Aspects, Integrative Systems, and Clinical Advances. (eds. McCann, S. M. et al.) 33–44 (New York Academy of Sciences, New York, 1998).

Schaufeli, W., Leiter, M., Maslach, C. & Jackson, S. The MBI–General Survey. In Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, Third Edition (eds. Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E. & Leiter, M. P.) 19–26 (Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, 1996).

Chirkowska-Smolak, T. & Kleka, P. The Maslach Burnout inventory-general survey: Validation across different occupational groups in Poland. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 42, 86–94. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10059-011-0014-x (2011).

De Jong Gierveld, J. & Kamphuis, F. The development of a Rasch-type loneliness scale. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 9, 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662168500900307 (1985).

Grygiel, P., Humenny, G., Rebisz, S., Świtaj, P. & Sikorska, J. Validating the Polish adaptation of the 11-item De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 29, 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000130 (2013).

Soldatos, C. R., Dikeos, D. G. & Paparrigopoulos, T. J. Athens insomnia scale: Validation of an instrument based on ICD-10 criteria. J. Psychosom. Res. 48, 555–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(00)00095-7 (2000).

Fornal-Pawłowska, M., Wołyńczyk-Gmaj, D. & Szelenberger, W. Validation of the Polish version of the Athens insomnia scale. Psychiatr. Pol. 45, 211–221 (2011).

McNeish, D. Thanks coefficient alpha, we’ll take it from here. Psychol. Methods 23, 412–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000144 (2018).

Flora, D. B. Your coefficient alpha is probably wrong, but which coefficient omega is right? A tutorial on using R to obtain better reliability estimates. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 3, 484–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245920951747 (2020).

Malkewitz, C. P., Schwall, P., Meesters, C. & Hardt, J. Estimating reliability: A comparison of Cronbach’s α, McDonald’s ωt and the greatest lower bound. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 7, 100368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2022.100368 (2023).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 (2003).

Rhemtulla, M., Brosseau-Liard, P. É. & Savalei, V. When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychol. Methods 17, 354–373. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029315 (2012).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Available at http://www.r-project.org/ (2023).

Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 48, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02 (2012).

Hu, L. T. & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 (1999).

Kline, R. B. Principles and Practices of Structural Equation Modelling. (Guilford Press, New York, 2005)

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312 (1981).

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M. & Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 43, 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8 (2015).

Hair Jr., J. F. et al. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook. (Springer Nature, Cham, 2021).

MacKinnon, D. P., Fairchild, A. J. & Fritz, M. S. Mediation analysis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 58, 593–614. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542 (2007).

Gonzalez, O., Valente, M. J., Cheong, J. & MacKinnon, D. P. Mediation/indirect effects in structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling (ed. Hoyle, R. H.) 409–426 (Guilford Press, New York, 2012).

Hom, M. A., Chu, C., Rogers, M. L. & Joiner, T. E. A meta-analysis of the relationship between sleep problems and loneliness. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 8, 799–824. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702620922969 (2020).

Mäkiniemi, J. P., Oksanen, A. & Mäkikangas, A. Loneliness and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: The moderating roles of personal, social and organizational resources on perceived stress and exhaustion among Finnish university employees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 7146. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137146 (2021).

Mokros, Ł, Świtaj, P., Bieńkowski, P., Święcicki, Ł & Sienkiewicz-Jarosz, H. Depression and loneliness may predict work inefficiency among professionally active adults. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 95, 1775–1783. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-022-01869-1 (2022).

Zarei, S. & Fooladvand, K. Mediating effect of sleep disturbance and rumination on work-related burnout of nurses treating patients with coronavirus disease. BMC Psychol. 10, 197. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00905-6 (2022).

Kuzey, C., Sait Dinc, M., Güngörmüş, A. H. & Antony, S. The mediating role of loneliness on the relationship between internet addiction and burnout levels: A PLS-SEM approach. J. Account. Fin. Audit. Stud. 9, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.32602/jafas.2023.001 (2023).

Westland, J. C. Lower bounds on sample size in structural equation modeling. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 9, 476–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2010.07.003 (2010).

Soper, D. S. A-priori sample size calculator for Structural Equation Models [Software]. Available at https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc (2024).

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W. & Sugawara, H. M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Methods 1, 130–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130 (1996).

Preacher, K. J. & Coffman, D. L. Computing power and minimum sample size for RMSEA [Computer software]. Available at http://quantpsy.org/ (2006).

Spithoven, A. W. M., Bijttebier, P. & Goossens, L. It is all in their mind: A review on information processing bias in lonely individuals. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 58, 97–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.003 (2017).

Wardle-Pinkston, S., Slavish, D. C. & Taylor, D. J. Insomnia and cognitive performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 48, 101205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2019.07.008 (2019).

Gordon, A. M., Mendes, W. B. & Prather, A. A. The social side of sleep: Elucidating the links between sleep and social processes. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 26, 470–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417712269 (2017).

Balbo, M., Leproult, R. & Van Cauter, E. Impact of sleep and its disturbances on hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis activity. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2010, 759234. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/759234 (2010).

Elder, G. J., Altena, E., Palagini, L. & Ellis, J. G. Stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: How can the COVID-19 pandemic inform our understanding and treatment of acute insomnia?. J. Sleep Res. 32, e13842. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13842 (2023).

Frank, M. G. & Heller, A. R. Sleep and emotional regulation. Sleep Med. Rev. 7, 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1087-0792(03)90047-1 (2003).

Zohar, A. & Tzischinsky, O. Sleep disturbances and emotional regulation: The role of the autonomic nervous system. Sleep Med. Rev. 44, 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2018.09.002 (2019).

Bakker, A. B. & de Vries, J. D. Job Demands-Resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety Stress Coping 34, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1797695 (2020).

Roczniewska, M. & Bakker, A. B. Burnout and self-regulation failure: A diary study of self-undermining and job crafting among nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 77, 3424–3435. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14872 (2021).

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E. & Sanz-Vergel, A. Job Demands-Resources theory: Ten years later. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 10, 25–53. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-053933 (2023).

James, S. M., Honn, K. A., Gaddameedhi, S. & Van Dongen, H. P. A. Shift work: Disrupted circadian rhythms and sleep-implications for health and well-being. Curr. Sleep Med. Rep. 3, 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40675-017-0071-6 (2017).

Boersma, G. J., Mijnster, T., Vantyghem, P., Kerkhof, G. A. & Lancel, M. Shift work is associated with extensively disordered sleep, especially when working nights. Front. Psychiatry 14, 1233640. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1233640 (2023).

Karatsoreos, I. N. Links between circadian rhythms and psychiatric disease. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 8, 162. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00162 (2014).

Walker, W. H. 2nd., Walton, J. C. & Nelson, R. J. Disrupted circadian rhythms and mental health. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 179, 259–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-819975-6.00016-9 (2021).

Masi, C. M., Chen, H.-Y., Hawkley, L. C. & Cacioppo, J. T. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 15, 219–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310377394 (2011).

Cain, M. K., Zhang, Z. & Bergeman, C. S. Time and other considerations in mediation design. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 78, 952–972. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164417743003 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Marta Robson for providing language assistance.

Funding

The study was supported by a grant of the National Centre for Research and Development (NCBR) No. I.PB.08 ‘Occupational burnout and depression in professions with exposure to high levels of occupational stress: determinants, prevalence, interrelations and mechanisms of impact on selected indicators of health, psychosocial functioning and occupational effectiveness’, implemented within the long-term program ‘Improvement of safety and working conditions’ coordinated by the Central Institute for Labour Protection – National Research Institute (CIOP-PIB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.Ś. and H.S.-J. devised the concept and procedures of the study. Ł.B., J.B. and J.J. consulted the concept and procedures of the study. J.J. supervised the data collection and prepared the database. Ł.K. and Ł.B. performed the statistical analysis. P.Ś., Ł.B., Ł.K. and H.S.-J. interpreted the data. P.Ś., Ł.B. and Ł.K. drafted the manuscript. All authors made revisions and approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Świtaj, P., Baka, Ł., Kapica, Ł. et al. Insomnia mediates the longitudinal association between loneliness and burnout among nurses. Sci Rep 15, 25384 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11264-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11264-8