Abstract

Rock burst events are frequently accompanied by the formation of extensive tensile cracks, with bedding plane dip angles fundamentally determining the tensile strength characteristics, crack propagation, and failure modes of coal measures. This study investigates the influence of bedding plane angles on the tensile mechanical behavior of coal rocks using PFC2D numerical simulations. Models with four distinct bedding angles (0°, 30°, 60°, 90°) were developed to analyze failure mechanisms under tensile loading. The results demonstrate three key findings: (1) both tensile strength and elastic modulus exhibit positive correlations with increasing bedding angle, with tensile strength showing greater sensitivity compared to the more gradual enhancement of elastic modulus. (2) failure patterns evolve characteristically with bedding orientation: (i) 0° specimens fail through horizontal tensile-shear composite fractures, (ii) 30° models display preferential brittle shear failure along bedding planes, (iii) 60° cases show 78% shear-dominated crack propagation parallel to bedding, while (iv) 90° configurations develop multidirectional cracking networks due to constrained bedding-parallel shear. (3) micromechanical analysis reveals that stress transfer mechanisms transition from loading-axis dominance at low angles (0°-30°), through bedding-aligned force chain concentration at intermediate angles (60°), to complex three-dimensional force redistributions at 90° where matrix-bedding interactions dominate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As coal mining progresses to greater depths, dynamic hazards such as rockbursts are becoming increasingly frequent, posing a significant threat to the safe mining of coal1,2,3. Rockburst is a dynamic phenomenon that occurs when the elastic deformation energy stored in the surrounding rock and coal mass of a mine roadway is released instantaneously, often accompanied by ejection of coal and rock, loud noises, and air blasts4,5,6,7. In China, rockbursts can be classified into three main types8: (1) Compression-induced rockburst. Under high stress, the stress state of coal and rock reaches or exceeds the peak strength and enters the plastic deformation stage. When subjected to mining-induced disturbances, the coal/rock structure becomes unstable, leading to a rockburst. (2) Roof failure-induced rockburst. The stability of the roof is governed by tensile stress. Under continued disturbance, microcracks propagate until the stability limit is reached, triggering a rockburst. (3) Fault-slip-induced rockburst. This type of rockburst is formed by shear instability of the faulted rock mass. When mining activities disturb the fault zone, fault slip is triggered, leading to a rockburst. Although different types of rockburst have distinct failure mechanisms (compression, tension, and shear)9,10,11 all involve rapid crack propagation during the sudden release of energy12,13,14 with tensile failure being a critical step for crack penetration. Notably, coal and rock are typical laminated sedimentary rocks characterized by well-developed bedding structures. As natural weak planes, bedding surfaces have lower bonding strength than the coal and rock matrix, resulting in significant anisotropy in the tensile strength of coal and rock. The degree of bedding development, dip angle, and bonding characteristics directly determine the strength characteristics, deformation behavior, and failure modes of coal and rock.

Current research on the bedding effect of rocks has predominantly focused on physical experiments and numerical simulations. In terms of physical experiments, Zhao et al.15 found that tensile strength depends on impact velocity and bedding orientation, while bedding roughness and discontinuity also influence tensile strength. Sun et al.16 observed that fracture propagation direction in coal is influenced by bedding dip angle, strength, and elastic modulus, whereas peak load correlates with bedding dip angle, thickness, and spacing. Song et al.17 reported a U-shaped relationship between cumulative AE energy and bedding dip angle, with time series fractal dimension (TRFD) positively correlating with AE counts. Li et al.18 demonstrated that AE energy exhibits a step change at the peak dynamic load, and the relationship between AE counts and time can be determined based on failure modes. Li et al.19 demonstrated that under similar strain rates, peak stress varies in a “U” shape with bedding dip angle, and the bedding effect weakens with increasing strain rate. Wang et al.20 revealed significant anisotropy in mechanical properties, with uniaxial compressive strength initially decreasing and then increasing with bedding angle, reaching its minimum at 60°. Additionally, 60° coal samples fail faster and exhibit the lowest dissipated energy. Regarding numerical simulations, Sun et al.21 employed a four-dimensional lattice spring model (4D-LSM) to establish coal-rock models with bedding angles ranging from 0° to 90° for modified semi-circular bending tests. Wang et al.22 used CDEM to develop numerical models of coal-rock containing bedding planes. Cong et al.23 applied the finite-discrete element method (FDEM) to create three-dimensional CMS models considering bedding dip angle and bedding strength. Yin et al.24 utilized PFC2D software to establish models of coal-rock combinations with single joints at various angles. Li et al.25 developed a bedding-containing rock model based on the discrete element method for notched semi-circular bending tests. Shen et al.26 employed FRACOD to develop anisotropic functions and suggested that strength anisotropy is generally considered more significant and important than modulus anisotropy, dominating the stability and failure modes of rock masses. Duan et al.27 established a numerical rock model capable of characterizing anisotropy based on DEM and conducted Brazilian splitting tests.

Although extensive research has been conducted on bedding-plane coal-rock, most studies have focused on its compressive failure, leaving the tensile mechanical properties inadequately explored. For investigating the tensile behavior of rocks, both direct and indirect tensile testing methods are commonly employed. Zhang et al.28 evaluated tensile strength using direct tension, curved compression splitting, and angular compression splitting tests. Their results demonstrated that indirect tensile tests tend to underestimate the actual tensile strength, thus recommending direct tension as the preferred method for accurate measurement. However, direct tensile testing of rocks remains challenging due to limitations in experimental setups, including difficulties in specimen gripping and procedural complexity. Despite significant improvements in testing apparatus by researchers29,30 physical experiments still entail high costs and time-consuming processes. In contrast, numerical simulations offer an effective solution to these challenges. Since the 1970s, the Discrete Element Method (DEM) has been applied to analyze rock mechanics problems, proving particularly advantageous for studying fracture propagation31. Consequently, DEM-based simulation of tensile failure in bedding-plane coal-rock emerges as an efficient and reliable alternative.

This study conducts numerical direct tension simulations on coal-rock specimens with different bedding angles. Using PFC2D7.0, we established four coal-rock models with bedding angles of 0°, 30°, 60°, and 90°. Through direct tension applied to the top and bottom of the models, we investigated the stress-strain relationships, elastic modulus, tensile strength, failure patterns, and force chain transmission characteristics across different bedding angles. The findings provide significant theoretical insights for understanding the formation mechanisms of rock bursts and establishing accurate disaster prediction methods, offering substantial engineering value.

Numerical modeling and micro parameter assignment

This study employs PFC2D7.0 to establish numerical coal-rock models with different bedding plane angles (0°, 30°, 60°, 90°), as shown in Fig. 1, to investigate the influence of bedding structures on the mechanical behavior of coal-rock under tensile loading. This article considers coal rock as a homogeneous body and begins research based on this assumption. The model parameters are adopted from Reference32 with the coal-rock model dimensions set at 100 mm in height and 50 mm in width. The particle radius in the model range from 0.28 mm (minimum) to 0.465 mm (maximum), comprising a total of 8,266 particles. A global damping coefficient of 0.7 was applied to facilitate model convergence. To account for the distinct mechanical properties between the coal-rock matrix and bedding plane weak interfaces, the parallel bond model (PBM)33,34 was employed to simulate the coal-rock matrix, while the smooth joint model (SJM)35,36 was used to represent the bedding media. The PBM consists of linear and parallel bond components. The SJM permits frictionless or low-friction sliding along predefined joint orientations while maintaining normal contact in the perpendicular direction. The modeling procedure involved: (1) generating the bulk model through random particle generation with PBM assignments for the coal-rock matrix; (2) determining bedding plane locations using discrete fracture network (DFN) methodology; and (3) assigning SJM properties to the bedding planes. By adjusting the bedding plane angles, four distinct coal-rock models were constructed with θ = 0°, 30°, 60°, and 90°, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The contact parameters were adopted from Reference32 with specific values provided in Table 1. The loading method of the model is displacement loading, with a loading speed of 10e-3 m/s.

Analysis and discussion of results

Stress-strain curves and key mechanical parameters

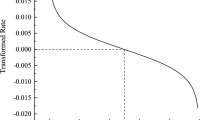

Measurement circles were set in the model to monitor the internal stress-strain conditions, and the stress-strain curves are plotted in Fig. 2. The Fig clearly shows that the bedding angle has a significant influence on the tensile mechanical behavior of coal-rock. The stress-strain curves of 0°, 60° and 90° bedding coal-rock are similar, showing certain plasticity after reaching peak strength. The stress-strain curve of 30° bedding coal-rock shows strong brittleness, with stress suddenly dropping to 0 after reaching peak strength. It can also be observed from the Fig that the 0° specimen has the lowest elastic modulus and peak strength, and its stress-strain curve shows typical plastic failure characteristics; the 30° specimen has slightly higher elastic modulus and peak strength than the 0° specimen; the 60° specimen shows more obvious growth in elastic modulus and peak strength; the 90° specimen has the highest elastic modulus and peak strength. The stress-strain curve of the 90° bedding angle sample in Fig. 2 is unusual. This discrepancy arises because the experiment used the measure function in PFC2d to monitor stress-strain behavior. In PFC2d, strain is calculated by measuring the strain increase rate and multiplying it by the time step. For the 90° sample, the post-failure strain appears to decrease because the strain growth rate becomes negative after failure. The mechanical behavior of the 90° bedding angle differs fundamentally from other angles: although the tangential bedding fails, it still retains some load-bearing capacity, leading to a more complex failure mode as shown in Fig. 4. In reality, the strain of the 90° model continues to increase after failure, but the strain growth rate slows significantly due to its remaining load-bearing capacity, causing the apparent decrease in measured strain.

To further analyze the influence of bedding angle on the mechanical properties of coal rock, Fig. 3 plots the elastic modulus and peak strength from Fig. 2 against bedding angle. The results demonstrate significant bedding effects on tensile strength variation. When θ = 0°, the tensile strength reaches its minimum value of 1.09 MPa. As θ increases, the tensile strength shows an upward trend, reaching its maximum value of 4.5 MPa at θ = 90°, representing a 57.1% decrease. The growth rates are 12.12% when θ increases from 0° to 30°, 72.37% from 30° to 60°, and reaches the maximum growth rate of 112.13% from 60° to 90°. These results indicate that bedding angle significantly affects tensile strength, with negligible bedding effects (growth rate < 12.23%) when θ ≤ 30°. In bedded coal rock, both the shear and tensile strengths of the coal matrix exceed those of the bedding planes, leading to stress concentration at bedding interfaces. Since the bedding planes’ shear strength exceeds their tensile strength, the overall tensile strength is controlled by the bedding planes’ tensile strength. With increasing θ, the normal component of tensile stress on bedding planes gradually decreases while the tangential component increases. Equation (1) calculations show decreasing normal stress and increasing shear stress at bedding interfaces, indicating a transition from pure tension to pure shear. Consequently, the overall tensile strength increases with θ.

where σc is the tensile stress on the coal rock, σn is the normal stress at the interface of the strata, τ is the tangential stress at the interface of the strata, and θ is the angle between the strata and the horizontal.

Figure 3 shows that the elastic modulus increases with bedding angle, though its growth rate is smaller than that of tensile strength, exhibiting a gentler curve. The measured elastic modulus values are 0.265 GPa (0°), 0.292 GPa (30°), 0.360 GPa (60°), and 0.409 GPa (90°). The corresponding growth rates are 10.10% (0°-30°), 23.29% (30°-60°), and 13.57% (60°-90°). This behavior reflects the controlling mechanism of bedding planes on stiffness: (1) At low angles (θ < 30°), tensile deformation is mainly resisted by bedding plane extension; (2) At moderate angles (30°≤θ ≤ 60°), deformation resistance comes from combined tension and slip along bedding planes; (3) At high angles (approaching 90°), where bedding planes align with the tensile direction, slip becomes the dominant deformation resistance mechanism, resulting in partial stiffness recovery. It can also be observed from Fig. 3 that when the bedding angle increases from 60° to 90°, the compressive strength of the model increases significantly, while the upward trend of the elastic modulus does not change much. According to Eq. (1), when the bedding angle is 90°, the bedding model undergoes the maximum shear, while the normal tension is almost zero. The shear strength between the bedding and coal rock is greater than the tensile strength. A bedding angle of 0° corresponds to a pure tensile state of the bedding, and 90° corresponds to a pure shear state. Thus, when the bedding angle is 60°—where the transition from tensile-shear composite to pure shear occurs—the strength increases significantly. Moreover, since the tangential stiffness of the coal rock is lower than the normal stiffness, the increase in the elastic modulus does not show a significant change.

Failure mode

The discrete fracture network (DFN) was used to monitor crack propagation during tension, where broken contacts are considered as fractures and can be classified as tensile or shear cracks based on stress conditions. Figure 4 shows the failure modes of coal-rock with different bedding angles. At θ = 0°, failure mainly consists of tensile fracture and shear damage between bedding planes in the middle of the model. At θ = 30°, two cracks appear, with a main fracture running from the middle left to the bottom right of the model, showing tension-shear composite failure along the bedding plane dominated by shear cracks. At this point the bedding planes begin to control the failure process, explaining the stress plunge observed in the section “Stress-strain curves and key mechanical parameters”. At θ = 60°, the model develops two main cracks and some scattered cracks (none penetrating the entire model), with cracks propagating along bedding planes showing shear slip failure and local tensile failure in some areas. At θ = 90°, shear cracks appear in the middle and lower parts of the model without full penetration of bedding, while horizontal tension-shear composite cracks develop on both sides of the coal-rock matrix, converging with the central shear crack. At θ = 90°, the bedding is mainly subjected to shear stress, and since the shear strength of bedding is greater than its tensile strength, partial coal-rock reaches maximum tensile stress before overall failure occurs.

Microcrack characteristics

The crack statistical results are shown in Fig. 5, and the proportions of the final shear cracks and tensile cracks after the model failure are plotted in Fig. 6. It can be seen from Fig. 5 that the crack number-strain curve is significantly affected by the bedding dip angle, and the curve shapes vary greatly. When θ = 0° (Fig. 5a), the crack evolution presents three-stage characteristics. In the initial stage (ε < 0.004), the model does not fail and no cracks are generated. In the crack propagation stage (0.004 < ε < 0.008), both shear cracks and tensile cracks start to increase sharply, and the number of shear cracks is more than that of tensile cracks. In the instability stage (0.008 < ε), the model failure reaches equilibrium, and the number of cracks no longer increases, with the final total number of cracks reaching 102. The crack proportions are shown in Fig. 6, where tensile cracks account for 43% and shear cracks account for 57%, indicating that coal rocks with parallel bedding are simultaneously subjected to shear and tensile effects during direct tension, with the shear effect being slightly stronger than the tensile effect.

When θ = 30° (Fig. 5b), the evolution pattern is completely different. When the strain is less than 0.0035, no damage occurs in the model. When the strain is between 0.0035 and 0.004, only some shear cracks appear. When the strain is between 0.004 and 0.0044, the number of cracks increases rapidly, with shear cracks outnumbering tensile cracks. When the strain exceeds 0.0044, the model undergoes unstable failure with no further increase in crack number, showing obvious brittleness as complete failure occurs within a short time, which is consistent with the stress-strain curve analysis results in the section “Stress-strain curves and key mechanical parameters”. The final total number of cracks reaches 122, with crack proportions shown in Fig. 6: 29% tensile cracks and 71% shear cracks. Compared with θ = 0°, the proportion of shear cracks increases significantly, and the overall model exhibits shear failure, indicating that the bedding planes begin to affect stress distribution and promote shear slip at this stage.

At θ = 60° (Fig. 5c), the crack evolution shows the same three-stage characteristics as θ = 0°. In the initial stage (ε < 0.005), the model remains intact with no crack formation. During the crack propagation stage (0.005 < ε < 0.009), shear cracks appear first, followed by tensile cracks. In the instability stage (ε > 0.009), the model reaches failure equilibrium with no further crack increase, ultimately producing 260 total cracks, consisting of 22% tensile cracks and 78% shear cracks. Compared to θ = 0° and θ = 30°, the total number of cracks increases significantly, indicating more severe damage. Meanwhile, the proportion of shear cracks further rises, demonstrating enhanced shear slip in the model.

At θ = 90° (Fig. 5d), due to the hysteresis observed in strain monitoring, the crack development also exhibits hysteresis behavior. When strain is below 0.007, the model remains intact with no crack formation. As strain increases between 0.007 and 0.014, shear cracks emerge first, followed by tensile cracks. When strain exceeds 0.014, the model undergoes unstable failure with no further increase in crack number, ultimately reaching a total of 683 cracks. Notably, the strain required for initial crack formation is significantly delayed compared to specimens with other bedding angles, while the final number of cracks at failure is the highest among all tested angles.

The fracture orientation statistics are presented in Fig. 7, which shows rose diagrams illustrating the fracture development characteristics of coal-rock models with different bedding angles. In these diagrams, each sector’s central angle represents fracture azimuth (ranging from 0° to 360°), while the radial length or area of the sector corresponds to the quantity or density of fractures within that orientation range. Larger sector areas indicate greater numbers of fractures in that particular direction.

For horizontal bedding (θ = 0°), Fig. 7a reveals that fractures are predominantly distributed in vertical (0°-60°) and horizontal (120°-180°) orientations, indicating preferential development of vertical and horizontal fractures under horizontal bedding conditions due to combined effects of bedding structure and loading configuration. With increasing bedding angle, significant changes occur in fracture development patterns. At θ = 30° (Fig. 7b), fractures concentrate toward vertical orientations, with dominant directions clustered around northeast orientations (approximately 0°~90°). When θ = 60° (Fig. 7c), fracture orientations become more concentrated within 20°~90° northeast directions. Under θ = 60° conditions, fracture development intensifies with slightly increased total fracture counts, and the primary fracture directions align with the bedding angle, demonstrating that failure primarily initiates along bedding planes to form dominant orientation patterns. Finally, at θ = 90° (Fig. 7d), the coal-rock model reaches maximum total fracture counts but displays more dispersed fracture distributions across 20°-180° orientations. Under vertical bedding conditions, shear stresses dominate at bedding-matrix interfaces. Before bedding planes reach peak shear strength, portions of coal matrix attain their maximum tensile strength, consequently promoting fracture development along multiple preferential directions and yielding the highest overall fracture density.

In summary, the bedding angle is a crucial factor controlling both the density and directional distribution of fractures in coal rock. As the bedding angle increases, the total number of fractures increases while the anisotropy of fracture orientations becomes more pronounced. Particularly at medium-low angles (30° and 60°), the bedding planes exert significant control over fracture orientation, resulting in highly concentrated directional fracture patterns.

Force chain characteristics

Figure 8 presents the force chain distribution characteristics of coal-rock models with different bedding angles after tensile failure. In the diagrams, red force chains represent compressive states between particles, blue force chains indicate tensile states, and white fracture-like patterns denote major failure cracks. For horizontal bedding (θ = 0°, Fig. 8a), the upper part of model fractures mainly shows tensile states while the lower part exhibits compressive states. The corresponding force chain distribution reveals that compressive chains form a network-like arrangement, creating load-bearing chain columns. Macroscopic failure manifests as splitting cracks along horizontal bedding planes, with both compressive and tensile chains distributed near these cracks, indicating that horizontal bedding plane cracking primarily results from local tension-shear composite stresses. The fracture of force chain networks at horizontal cracks leads to interruption and redistribution of stress transmission paths. With increasing bedding angle, significant changes occur in force chain distribution and failure patterns. At θ = 30° (Fig. 8b), an inclined penetrating crack develops in the lower model section. The entire model shows tensile states with relatively uniform tensile chain distribution. Chain properties transition across the penetrating crack - compressive above and tensile below the crack. When bedding angle increases to 60° (Fig. 8c), bedding planes strongly influence force chain distribution. Compressive stress zones primarily concentrate along model edges or local interior regions, while tensile stresses distribute in the interior and lower sections. For vertical bedding (θ = 90°, Fig. 8d), the model demonstrates more complex force chain distribution. Major compressive chains concentrate in the upper-left section and around transverse cracks, alternating with tensile chains in central and bottom regions, creating intricate distribution patterns. This complexity indicates that under vertical bedding conditions, stress transmission along loading direction interacts with vertically-oriented bedding weaknesses, resulting in more complicated force chain networks and failure modes where stress distribution is no longer simply dominated by bedding orientation.

The bedding angle significantly influences the force chain structure and stress transmission paths within coal-rock. Under horizontal bedding conditions (θ = 0°), force chains primarily align with the loading direction, resulting in splitting failures along bedding planes. As the bedding angle increases, force chains become progressively guided by bedding orientation, particularly at medium-low angles (30° and 60°), where major compressive stresses concentrate within shear bands formed along bedding directions, exhibiting strong force chain anisotropy. Under vertical bedding (θ = 90°), the force chain distribution and failure patterns reflect combined effects of both loading direction and vertical bedding planes, forming more complex force chain networks and failure paths.

Figure 9 presents the distribution characteristics of internal contact force magnitudes in coal-rock models with different bedding angles during loading until failure. Under significant external forces, relative deformation occurs between particles, forming force chains. Areas with stronger deformation develop high-force chains that transmit greater forces, while areas with weaker deformation form low-force chains that bear smaller forces.

For the coal-rock model with horizontal bedding (θ = 0°), as shown in Fig. 9a, after the formation of macroscopic horizontal cracks, larger contact forces are predominantly concentrated between the two cracks, forming the primary force chains that bear the remaining load. The strongest forces occur near crack tips or stress concentration zones, reaching a maximum value of 1.96 kN.

With increasing bedding angle, the distribution of contact forces and the morphology of force chain networks undergo significant changes. At a bedding angle of 30° (Fig. 9b), the penetrating crack shows no evident stress concentration. However, stress concentration appears at the tip of non-penetrating cracks, reaching a maximum value of 2.48 kN. Although force chains are not completely parallel to the macroscopic cracks, numerous high-force chains are observed at the tips and edges of non-penetrating crack regions, indicating that stresses begin to concentrate toward weak plane areas.

When the bedding angle reaches 60° (Fig. 9c), the bedding planes primarily control stress transmission and failure patterns. Macroscopic failure forms two inclined non-penetrating cracks that are essentially aligned with the bedding direction. The contact force distribution shows that larger contact forces are concentrated along these inclined cracks. These high-strength force chains constitute the main load-bearing framework, demonstrating that stresses are effectively “guided” and concentrated along the weak bedding planes. Contact forces in regions outside the non-penetrating cracks are relatively low, with loads mainly transmitted through the channel between the two non-penetrating cracks. The maximum contact force value in the Fig shows a significant increase compared to other angles, reaching 4.828 kN, indicating a high stress concentration effect on bedding planes at 60° bedding angle.

For vertical bedding (θ = 90°), as shown in Fig. 9d, the model’s failure mode may include both bedding-parallel splitting and bedding-perpendicular fractures, forming complex stair-step cracks. The contact force distribution reveals that forces no longer concentrate at crack tips but distribute throughout the model interior, with multi-directional force concentrations near stair-step cracks. The distribution features both vertically-oriented primary force chains and high-contact-force zones at transverse cracks or deflection regions. This pattern reflects how vertical bedding obstructs and deflects crack propagation paths, causing stress concentrations within the complex fracture network and resulting in higher overall load-bearing capacity. Unlike the complete stress concentration observed at 0°, 30° and 60°, the 90° case shows more dispersed high-contact-force distribution with localized peaks, while the maximum contact force decreases compared to 60°.

The bedding angle significantly influences the magnitude, spatial distribution, and structural evolution of internal contact forces in coal-rock models. Horizontal bedding (θ = 0°) leads to stress concentration above and below horizontal cracks, while inclined bedding (θ = 30°~60°) facilitates high stress concentration along bedding planes, forming dominant force chains that reveal the mesoscopic mechanism of weak-plane-guided shear failure. Vertical bedding (θ = 90°) generates complex stress distributions and stair-step cracks, reflecting the interaction between vertical bedding planes and the coal-rock matrix. These mesoscale contact force distribution characteristics provide direct explanations for the differences in macroscopic strength and failure patterns of bedded coal-rock under tensile loading.

Conclusions

This study is based on the discrete element method of PFC2D. Numerical models of coal rocks with different bedding dip angles (0°, 30°, 60°, 90°) are constructed. The influence of the bedding structure on the tensile mechanical behavior of coal rocks is systematically analyzed, and the failure mechanism is revealed. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

Both tensile strength and elastic modulus exhibit significant enhancement with increasing bedding angle. The 90° bedding specimen achieves maximum tensile strength. The elastic modulus demonstrates more gradual growth, indicating distinct control mechanisms for stiffness versus strength, primarily governed by coupled slip-tension interactions along bedding planes.

-

(2)

With the increase of bedding angle, the failure mode undergoes significant changes. The larger the bedding angle, the more severe the failure, manifested as the controlling effect of bedding shear strength on overall failure.

-

(3)

The transmission characteristics of the force chain are also significantly related to the bedding angle. As the bedding angle increases, the force chain exhibits a transition from obvious stress concentration to uniform stress distribution. The uniform force chain distribution improves the load-bearing capacity of the model, and therefore, the overall strength also increases.

Data availability

The related data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

References

Li, H. R. et al. Granite strainbursts induced by true triaxial transient unloading at different stress levels: insights from excess energy ∆E. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2025.01.020 (2025).

Gale, W. J. A review of energy associated with coal bursts. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 28, 755–761 (2018).

Pan, Y., Song, Y., Luo, H. & Xiao, Y. Coalbursts in china: theory, practice and management. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 16, 1–25 (2024).

Li, H. R., He, M. C., Qiao, Y. F., Cheng, T. & Han, Z. Y. Assessing burst proneness and seismogenic process of anisotropic coal via the realistic energy release rate (RERR) index. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 58, 2999–3013 (2024).

Hu, J. et al. Rockburst hazard control using the excavation compensation method (ECM): A case study in the Qinling water conveyance tunnel. Engineering 34, 154–163 (2024).

Cheng, T. et al. Experimental investigation on the influence of a single structural plane on rockburst. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 132, 104914 (2023).

Hu, J. et al. Control effect of negative poisson’s ratio (NPR) cable on Impact-Induced rockburst with different strain rates: an experimental investigation. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56, 5167–5180 (2023).

Pan, Y. S., Li, Z. H. & Zhang, M. T. Distribution, type, mechanism and prevention of rockburst in China. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 1844–1851 (2003).

Gao, X., Pan, Y. & Zhao, T. The critical stress of roadway coalburst based on the general energy criterion. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. (2025).

Dai, L. et al. New criterion of critical mining stress index for risk evaluation of roadway rockburst. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 55, 4783–4799 (2022).

Dai, L. et al. Parameter design method for destressing boreholes to mitigate roadway coal bursts: theory and verification. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 57, 9539–9556 (2024).

Ma, G. et al. Mechanical and damage properties study of rocks with different joint inclinations under seepage–stress coupling: insights based on energy theory. Comput. Part. Mech. (2025).

Li, H. R. et al. Effect of water on mechanical behavior and acoustic emission response of sandstone during loading process: phenomenon and mechanism. Eng. Geol. 294, 106386 (2021).

Li, H. R. et al. Effect of water saturation on dynamic behavior of sandstone after wetting-drying cycles. Eng. Geol. 319, 107105 (2023).

Zhao, Y., Zhao, G. F., Jiang, Y., Elsworth, D. & Huang, Y. Effects of bedding on the dynamic indirect tensile strength of coal: laboratory experiments and numerical simulation. Int. J. Coal Geol. 132, 81–93 (2014).

Sun, Z. et al. Effects of bedding characteristics on crack propagation of coal under mode II loading: laboratory experiment and numerical simulation. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 17, 1037–1052 (2025).

Song, H., Zhao, Y., Elsworth, D., Jiang, Y. & Wang, J. Anisotropy of acoustic emission in coal under the uniaxial loading condition. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 130, 109465 (2020).

Li, J., Zhao, J., Wang, H. C., Liu, K. & Zhang, Q. B. Fracturing behaviours and AE signatures of anisotropic coal in dynamic Brazilian tests. Eng. Fract. Mech. 252, 107817 (2021).

Li, J. et al. Mechanical anisotropy of coal under coupled biaxial static and dynamic loads. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 143, 104807 (2021).

Wang, Y., Zhao, Z., Hui, Z., Hao, J. & Zhang, J. Mechanical responses of bedding coals under uniaxial compression: insights from deformation, energy and acoustic emission characteristics. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 22, e04404 (2025).

Sun, Z. et al. Effect of size and anisotropy on fracture process zone of coal: an experiment and numerical simulation. Eng. Fract. Mech. 306, 110227 (2024).

Wang, W., Zhao, Y., Sun, Z. & Lu, C. Effects of bedding planes on the fracture characteristics of coal under dynamic loading. Eng. Fract. Mech. 250, 107761 (2021).

Cong, R. et al. Influence of interfacial properties on mechanical behaviors and failure patterns of coal–measure thin interbedded rocks under uniaxial compression using 3D FDEM. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 58, 3589–3610 (2025).

Yin, D., Chen, S., Liu, X. & Ma, H. Effect of joint angle in coal on failure mechanical behaviour of roof rock–coal combined body. Q. J. Eng. Geol.Hydrogeol. 51, 202–209 (2018).

Li, Y., Hu, Y. & Zheng, H. Influence of bedding on fracture toughness and failure patterns of anisotropic shale. Eng. Geol. 341, 107730 (2024).

Shen, B., Siren, T. & Rinne, M. Modelling fracture propagation in anisotropic rock mass. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 48, 1067–1081 (2015).

Duan, K. & Kwok, C. Y. Discrete element modeling of anisotropic rock under Brazilian test conditions. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 78, 46–56 (2015).

Zhang, S., Miao, X. & Zhao, H. Influence of test methods on measured results of rock tensile strength. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 28 (1999).

Okubo, S. & Fukui, K. Complete stress-strain curves for various rock types in uniaxial tension. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 33, 549–556 (1996).

Nova, R. & Zaninetti, A. An investigation into the tensile behaviour of a schistose rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 27, 231–242 (1990).

Peng, S., Li, X., Li, C., Liang, L. & Huang, L. Crack-closure behavior and stress-sensitive wave velocity of hard rock based on flat-joint model in particle-flow-code (PFC) modeling. Comput. Geotech. 170, 106320 (2024).

Ou, J. et al. Numerical simulation of coal’s mechanical properties and fracture process under uniaxial compression: dual effects of bedding angle and loading rate. Processes 12, 2661 (2024).

Potyondy, D. O. & Cundall, P. A. A bonded-particle model for rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 41, 1329–1364 (2004).

Fan, Z. et al. 3D anisotropic microcracking mechanisms of shale subjected to direct shear loading: A numerical insight. Eng. Fract. Mech. 298, 109950 (2024).

Pierce, M., Cundall, P., Potyondy, D. & Ivars D.M. A synthetic rock mass model for jointed rock. OnePetro (2007).

Noori, M. et al. An experimental and numerical study of layered sandstone’s anisotropic behaviour under compressive and tensile stress conditions. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 57, 1451–1470 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Key Research and Development Program of China under Grant 2023YFC3008901, in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 42230811.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Key Research and Development Program of China under Grant 2023YFC3008901, in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 42230811.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Zh. and E.W.; writing-original draft, H.Zh.; project administration, J.Y.; investigation, B.M. and D.X. and X.T.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Wang, E., Yue, J. et al. DEM simulation study on the mechanical and micro-fracture characteristics of jointed coal under direct tensile conditions. Sci Rep 15, 30812 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11287-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11287-1