Abstract

Protein solubility problems arise in a wide range of applications, from antibody development to enzyme production, and are linked to several major disorders, including cataracts and Alzheimer’s diseases. To assist scientists in designing proteins with improved solubility and better understand solubility-related diseases, we introduce SOuLMuSiC, a computational tool for the fast and accurate prediction of the impact of single-site mutations on protein solubility. Our model is based on a simple artificial neural network that takes as input a series of features, including biophysical properties of wild-type and mutated residues, energetic values computed using various statistical potentials, and mutational scores derived from protein language models. SOuLMuSiC has been trained on a curated dataset of about 700 single-site mutations with known solubility values, collected and manually verified from original literature. It significantly outperforms current state-of-the-art predictors in strict cross validation: the Spearman correlation reaches 0.5 when solubility changes are represented categorically; for the subset with quantitative values, it increases to 0.7. SOuLMuSiC also shows good performance on external datasets containing high-throughput enzyme solubility-related data as well as protein aggregation propensities. In summary, SOuLMuSiC is a valuable tool for identifying mutations that impact protein solubility, and can play a major role in the rational design of proteins with improved solubility and in understanding genetic variants’ effect. It is freely available for academic use at http://babylone.ulb.ac.be/SoulMuSiC/.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Solubility is a key biophysical property of proteins, the lack of which is often a major bottleneck for their production and storage1,2,3. Numerous applications in protein structure determination1, pharmaceutics (e.g., production of protein-based therapeutics)4,5, and biotechnology (e.g., protein heterologous expression)6,7 require high-concentration protein formulation. Moreover, problems related to poor protein solubility and aggregation are central in a wide series of protein misfolding-related diseases, also known as proteinopathies. For example, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases8,9 are characterized by the growth of insoluble deposits of misfolded proteins, cataracts are related to a decrease in the solubility of human \(\gamma\)-crystallin10,11, and amylin (Islet amyloid polypeptide - IAPP) is involved in diabetes12. The different solubility states of these proteins are also important for understanding how they spread and propagate between cells13.

Despite the crucial importance of protein solubility and the considerable efforts made by the scientific community, a full comprehension of the mechanisms behind protein solubility remains out of reach. Solubility is influenced by a complex interplay of intrinsic factors such as residue-residue interactions, protein flexibility, amino-acid composition, and hydrophobicity, as well as extrinsic variables such as pH, environmental temperature, ionic strength, and protein concentration2,14,15,16,17.

In recent decades, multiple experimental and computational approaches have been developed to engineer proteins with improved solubility properties3,18,19. For example, when inclusion bodies form in heterologous expression, experimental protocols, including the solubilization of these bodies through the addition of denaturant compounds followed by the refolding of the solubilized proteins, have been designed to get bioactive recombinant proteins20,21. Another experimental approach to enhance the solubility of a target protein involves fusing it with solubility-enhancing tags, even though this requires additional chromatographic steps to obtain tag-free recombinant proteins22.

All these procedures remain, however, labor-intensive and quite unsatisfactory. Therefore, computational methods have been designed to speed up and complement the experimental approaches. A series of methods for predicting the solubility of a full protein have been developed, which leverage experimental solubility data23 to train computational models15,24,25,26,27,28,29,30.

The challenge of predicting the impact of mutations on protein solubility has been underinvestigated due to the scarcity of mutagenesis data. Indeed, only recently has a database of mutations with known changes in solubility been collected31. Moreover, the variability in environmental conditions and in the methods used for variant characterization make constructing datasets and testing variant predictors challenging.

Over the past decade, a few methods have been developed to address this challenge, ranging from simple linear combinations of features to machine learning approaches, either considering the amino-acid sequence or the three-dimensional structure. Renowned methods include CamSol32, SODA33 and PON-Sol234. However, these methods do not achieve satisfactory performance and moreover, the limited datasets they use for training make them prone to overfitting. A rigorous benchmark of their performances does not exist at the moment in the literature. For these reasons, we proceeded in this study to collect and manually curate a new dataset of mutations with an experimentally determined solubility value, and used it to develop a new method called SOuLMuSiC for the prediction of the impact of mutations on solubility. We compared SOuLMuSiC’s performance with the above mentioned algorithms and tested its ability to generalize to unseen data.

Methods

Dataset construction and curation

We collected a set of mutations whose effects on protein solubility have been experimentally characterized. Although protein solubility can be rigorously defined in thermodynamics as the protein concentration in a saturated solution that is in equilibrium with a solid phase2, its experimental measurement is far from trivial. Different techniques were used to estimate the solubility of proteins, either directly or indirectly35,36. They include measuring protein activity in a pellet after centrifugation37, sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)38, and dynamic light scattering39.

To set up our first mutation dataset \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\), we started to collect mutations and their experimentally measured solubility changes :

from the mutational solubility database SoluProtMutDB31. We then performed a literature search involving manually reviewing and curation of each SoluProtMutDB entry in the original literature to correct possible errors. Additionally, we extended the search to incorporate recent literature and patent data that were not included in SoluProtMutDB. We excluded data originating from high-throughput techniques such as fluorescence-activated cell sorting, and from mutations in membrane proteins. We focused exclusively on single-site mutations. This led to a total of 702 curated entries in \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\).

Due to the heterogeneity of experimental approaches and the dependence of solubility on the environmental conditions used in the experiments, such as pH, temperature, and ion buffer, the quantitative values of the changes in solubility upon mutation are often not precisely reported in the original articles. Only 225 entries out of 702 have a numerical estimation of \(\Delta S\) (in %). The remaining entries are annotated by their authors with qualitative labels such as ’strongly decrease/increase solubility’, ’decrease/increase solubility,’ or ’no impact.’ We therefore decided to use five discrete solubility scores (−3, −1, 0, 1, 3) or equivalently, five solubility classes (− −, −, =, +, ++). We classified the effects of mutations into these classes according to qualitative labels or, when available, based on their reported \(\Delta S\) values, as defined in Table 1. Negative solubility scores represent a decrease in solubility upon mutation and positive values, an increase. A value of zero indicates no significant change in solubility. We also defined the subset of \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\) that contains the 225 entries with quantitative \(\Delta S\) values, called \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}^Q\).

We collected the 3-dimensional (3D) structures of all wild-type proteins in \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\). We considered the experimental structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB)40 when available, but only if their resolution was smaller than 2.5 Å and their sequence 100% identical to the one considered. Otherwise, we modeled the structure using AlphaFold 241. In the few cases in which the oligomeric structures were too large to be modeled with AlphaFold, we used the homology modeling algorithm SWISS-MODEL42. The final dataset \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\) consists of 702 mutations with experimentally characterized effects on protein solubility, inserted in 80 proteins with experimental or modeled structures. For more details about the \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\) dataset, see Supplementary Section 1.

We set up a second dataset, called \(\mathcal {D}_{Inv}\), containing the reverse mutations of \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\). More precisely, for each mutation (wt \(\rightarrow\) mut) in \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\) with a given \(\Delta S\) value, we included the reverse mutation (mut \(\rightarrow\) wt) in \(\mathcal {D}_{Inv}\) and assigned it a value of \(-\Delta S\). We created this dataset to test the antisymmetry properties of our predictor, as non-symmetric models that are biased towards the training set are often constructed, as shown in43. The structures of the 702 mutant proteins in \(\mathcal {D}_{Inv}\) were modeled with the homology algorithm Modeller44 using as template the structures contained in \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\).

As an additional test mutation dataset, called \(\mathcal {D}_{LGK}\), we used solubility data of Levoglucosan kinase (LGK) from Lipomyces starkeyi. This enzyme catalyzes the phosphorylation of levoglucosan45. Deep mutational scanning was performed on LGK using yeast surface display (YSD)46: proteins were fused with an N-terminal domain to localize the protein on the outer cell surface, and with a C-terminal epitope tag, which binds to a fluorescent antibody, enabling the identification of only the variants expressed on the cell surface. Misfolded protein variants are less expressed on the cell surface as the proteasome degrades them to ensure protein quality control. In total, \(\mathcal {D}_{LGK}\) consists of 6,246 single-site mutations with known solubility values. Note that these values are only partially related to real solubility as the proteasome can also degrade misfolded soluble proteins. The structure that we used for LGK is homodimeric and has the PDB code 4ZFV.

In the last dataset, referred to as \(\mathcal {D}_{A\beta }\), we collected the aggregation propensity of variants of A\(\beta\)42, a protein known to play a key role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. The variant scores were measured47 using a yeast-based selection assay in which A\(\beta\) is fused to the essential protein dihydrofolate reductase. Consequently, the aggregation of the variants is inversely related to the yeast growth. In total, we collected 790 variants with known changes in aggregation propensity. These scores are only partially related to solubility, as aggregation phenomena differ from poor solubility precipitation. The structure that we used for A\(\beta\)42 has the PDB code 1IYT.

The datasets \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\), \(\mathcal {D}_{Inv}\), \(\mathcal {D}_{LGK}\) and \(\mathcal {D}_{A\beta }\), as well as all structures used in this study, can be retrieved from our GitHub repository at github.com/3BioCompBio/SOuLMuSiC.

Features

In our SOuLMuSiC model, we used two types of features: structure-based and sequence-based. The former are mainly based on statistical potentials, and the latter, on various amino-acid scales and on protein large language models. Below, we provide a brief description of these features.

\(\bullet\) Statistical potentials, which are well-known mean force potentials extracted from frequencies of associations between sequence elements, se, and structure motifs, st, in datasets of protein structures48,49. Using this formalism, the folding free energy \(\Delta W(st, se)\) of the sequence-structure pair (st, se) can be computed in terms of the probabilities of se, st and (st, se) using the inverse Boltzmann law, as defined in the first equality :

where \(k_B\) is the Boltzmann constant and \(T\) the absolute temperature taken to be room temperature49. As shown in the second approximate equality, the probabilities P can be estimated from the frequencies F of observation of se, st and (st, se) in a high-quality, non-redundant dataset of experimental protein 3D structures.

In our model, we used four types of statistical potentials, differing in the structure and sequence elements considered. Their list and characteristics are given in Table 2. Among these four potentials, two describe local interactions along the polypeptide chain and two are distance potentials that describe tertiary interactions and the likelihood of amino acids being separated by specific spatial distances. Note that more potentials can be defined, but we combined some of them to limit the number of free parameters that we have to optimize and thus to avoid overfitting.

Once these potentials were derived, we used them to compute the change in folding free energy \(\Delta \Delta G\) between the wild type (wt) and mutant (mut) proteins. Considering for example the distance potentials \(\Delta W_{sds}\) defined in Table 2, the associated free energy change \(\Delta \Delta G_{SDS}\) is defined as:

where

with N the protein length, \(s_{i}\) and \(s_{j}\) the sequence types of residues i and j, and \(d_{ij}\) the distance between the geometric side chain centers of residues i and j. The sum is thus over all residue pairs in the protein. Analogous expressions can be derived for the other potentials. In total, we considered four types of folding free energy terms: \((\Delta \Delta G_{SA} + \Delta \Delta G_{SSA})\), \((\Delta \Delta G_{ST} + \Delta \Delta G_{SST})\), \(\Delta \Delta G_{SDS}\), and \(\Delta \Delta G_{STD}\). They constitute four of the input features of our model.

For technical details on the construction and implementation of statistical potentials,we refer the reader to50,51.

-

Amino-acid scale-based features. We used four sequence-based features that are essentially amino-acid scales, and a fifth one corresponding to the large language model (LLM) ESM-1v. They are described below; the values for the four former scales can be found in our GitHub repository github.com/3BioCompBio/SOuLMuSiC.

-

\(\Delta\)Hydro is the difference between the hydrophobicity of the mutant and wild-type residues. The hydrophobicity scale we used is taken from55. It shows the best correlation with experimental solubility values, compared to the other tested scales such as the Kyte-Doolittle scale56 and the Janin scale57.

-

\(\Delta\)Aro is the difference in aromaticity between the mutant and wild-type residues. The aromaticity is considered equal to one for PHE, TYR, and TRP, and equal to zero for all other amino acids.

-

\(\Delta\)Iso is related to the isoelectric point Iso of the amino acid under consideration. As the solubility of proteins is minimal near the isoelectric pH58,59 and our predictions are for neutral pH, i.e. seven, we defined the feature \(\Delta\)Iso as the difference of (Iso\(-7\))\(^2\) for mutant and wild-type proteins:

$$\begin{aligned} \Delta \text {Iso}= ( \text {Iso}_{mut} - 7)^2 - ( \text {Iso}_{wt} - 7)^2 \end{aligned}$$(5) -

\(\Delta \Delta\)Apaac is defined from the amphiphilic pseudo amino-acid composition. Apaac describes the hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity distribution patterns along the protein chain and therefore includes sequence-order effects60. For a given protein, the Apaac per residue type is its frequency normalized by a factor that includes the correlation effects between hydrophobic or hydrophilic residues along the chain. We downloaded the dataset15, in which about 11,000 protein sequences were experimentally identified as soluble or insoluble. For each of these two sets, we calculated the Apaac score per amino-acid type using the protr package61 and averaged them over all sequences in each of the two sets. The logarithm of the ratio between Apaac scores of soluble and insoluble sets yields the \(\Delta\)Apaac index. \(\Delta \Delta\)Apaac is then computed as the difference between the mutant and wild-type \(\Delta\)Apaac values.

-

-

Protein Language models (pLM). As last sequence-based feature, we leveraged ESM (ESM-1v), a freely available unsupervised pLM machine learning model that predicts the variant effects from the amino-acid sequence. It is based on a 650M parameter transformer language model with zero-shot inference62 trained on UniRef90 2020-0363. Including this model in our predictors allows us to leverage the evolutionary information embedded in the complex architecture of the pLM model64, without the need of performing a multiple sequence alignment for the target protein, thus preserving speed and scalability.

The correlations between the different features used are examined in Supplementary Section 3.

Artificial neural network models

Our model’s input are the nine features described in the previous subsection: four folding free energy terms computed from statistical potentials: \((\Delta \Delta G_{SA} + \Delta \Delta G_{SSA})\), \((\Delta \Delta G_{ST} + \Delta \Delta G_{SST})\), \(\Delta \Delta G_{SDS}\), and \(\Delta \Delta G_{STD}\); four sequence-based features that depend on the similarity of the wild-type and mutant amino acids, i.e. their change in hydrophobicity (\(\Delta\)Hydro), aromaticity (\(\Delta\)Aro), isoelectric point (\(\Delta\)Iso), and amphiphilic pseudo amino-acid composition (\(\Delta \Delta\)Apaac); ESM that represents the predicted effect of the mutation on protein fitness estimated using the ESM-1v pLM.

We chose to combine this set of features using a simple artificial neural network. We explored more complex architectures but they potentially lead to overfitting due to the limited size of the dataset. This point is discussed in Supplementary Section 2. Our approach is analogous to that of the PoPMuSiC and HoTMuSiC algorithms50,65, i.e., we defined the perceptron activation functions to be sigmoid functions of the solvent accessibility A of the mutated residues. This involves weighting the input features differently in terms of the per-residue solvent accessibility, as different potentials and features of amino acids are known to contribute differently in the protein core and on the surface66.

More precisely, the SOuLMuSiC model reads as:

where \(\beta\) can be equal to 1 or \(-1\), depending on whether the input structure is a globular protein or an insoluble supramolecular homopolymer of proteins, such as amyloid fibrils, and \(\alpha _i(A)\) \((i=1,.., 9)\) are sigmoid functions expressed as :

This yields 27 free parameters \((a_i, b_i, c_i)\), which were identified by minimizing the root mean square error (RMSE) between experimental and predicted changes in solubility \(\Delta S\) upon mutations in the \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\) dataset used as training set:

where N is the number of mutations in \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\). Minimization is performed using the NMinimize routine implemented in67, which employs a standard gradient descent algorithm with default settings and random parameter initialization. Performance is evaluated using a strict leave-one-out cross-validation process, where all mutations in one protein are, in turn, excluded from the training set and then predicted.

Results

Prediction performances

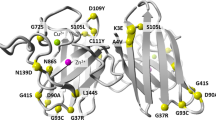

We tested the prediction performance of SOuLMuSiC on different datasets. We started with the training set \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\), and evaluated the performance in leave-one-out cross-validation at protein level. The distributions of the cross-validated SOuLMuSiC scores for all \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\) entries, separated as a function of their experimentally characterized solubility score defined in Table 1, are shown in Fig. 1. We clearly observe that SOuLMuSiC can distinguish between different solubility classes and identifies with fair accuracy which mutations make proteins more soluble or less soluble.

One of the metrics that we used to evaluate the overall performance of SOuLMuSiC is the Spearman correlation coefficient \(\rho\) between the predicted and experimental \(\Delta S\) score values (\(-3\), \(-1\), 0, 1, 3). SOuLMuSiC achieves a \(\rho\) value of 0.49 in the dataset \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\) with the above-mentioned strict cross-validation procedure. This is a fairly strong correlation considering the variability in experimental setups used to determine the \(\Delta S\) values.

Notably, when computing the correlation on the subset \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}^Q\) of \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\) consisting of 225 entries for which a quantitative \(\Delta S\) value is available (see Section 2.1), we observe a significantly higher agreement, with a Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.70. This represents a strong performance, especially considering the simplicity of the model and the limited size of the training dataset.

Our SOuLMuSiC model was only trained on single-site mutations of \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\). Nevertheless, we tested it on a small set of multiple mutations collected from the literature. The correlation coefficient of course dropped but remained good, as shown in Supplementary Section 4.

We also used other performance metrics to evaluate SOuLMuSiC, i.e. multiclass precision, recall, and balanced accuracy (BACC). They are defined and given in Table 3. To convert the SOuLMuSiC score into a multiclass prediction, we set thresholds at the midpoint between the average SOuLMuSiC scores of each pair of adjacent classes. The global value of each metric is obtained by averaging the metric value over each of the five classes.

The global BACC, that in the case of multiclass classification is defined as the average recall, is equal to 0.36, which has to be compared to the expected BACC of 0.2 for a random prediction by a five-class classifier. Although this score is not outstanding, a closer look at the data reveals that the classes of variants with a significant impact on solubility are well predicted, with recall scores equal to 0.64. Other classes are, however, less accurately predicted, which may be partly due to the way we defined these classes. For example, we labeled a change in solubility as “neutral” if it ranges between −10% and +10% compared to the wild type, while the “+” and “−” classes cover changes between +10% to +50% and −10% to −50%, respectively. Given that solubility values can greatly vary according to the experimental methods and environmental conditions, it is unsurprising that the model has more difficulty distinguishing classes with small changes in solubility values, as some misclassifications may arise from inherent experimental uncertainty.

The neutral class has much better precision and much worse recall, meaning that the number of false negatives is much larger than the number of false positives. This is due to the choice of the classification thresholds, chosen to favor the prediction of the extreme classes over the neutral class.

SOuLMuSiC’s score distribution in the \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\) dataset, obtained in protein-level leave-one-out cross validation, for the five classes of mutations experimentally shown to affect solubility from strongly increasing (++) to strongly decreasing (− −), as defined in Table 1.

Comparison with other predictors

We compared SOuLMuSiC’s performance on the \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\) dataset with state-of-the-art solubility predictors. Note that, as described in the previous subsection, a strict leave-one-out cross validation was performed to provide a reliable assessment of SOuLMuSiC’s performance and thus ensure a fair comparison with other methods. Most of the latter methods use biophysical data at amino-acid level such as hydrophobicity or isoelectric point, and sequence-based information such as residue propensities to adopt secondary structures or residue flexibility in a given sequence window. Only few use structural information (i.e., SOuLMuSiC, CamSol32, SOLart27). Recent tools, such as SOuLMuSiC, NetSolP30, and PON-Sol234, also integrate pLM-based predictions, following recent advances in the pLM field62.

Among the tested prediction methods, only 4 (SOuLMuSiC, PON-Sol234, CamSol32, SODA33) directly predict solubility changes upon mutations, with the former three providing a continuous score and the latter being a binary classifier. Seven others (Protein-Sol26, SoDoPE15, SoluProt28, ccSOLomics25, NetSolP30, Skade29, SOLart27) predict protein solubility values S; in these cases, the \(\Delta S\) values were obtained by subtracting the S values of wild-type and mutated proteins. Two predictors, PoPMuSiC and ESM, predict the folding free energy changes upon mutation (\(\Delta \Delta G\)s) and the fitness changes upon mutation, respectively.

For all these predictors, we computed the Spearman correlation coefficients \(\rho\) between the predicted and experimental \(\Delta S\) values for all the entries in the \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\) dataset. We see that SOuLMuSiC largely outperforms the other predictors, achieving a solid Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.49 in leave-one-out cross-validation. Note that PON-Sol2 is trained on a dataset that largely overlaps with \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\), while all other predictors are essentially blind to it. Although predictors claim higher accuracy in their papers, when these models are tested on new, larger, and highly curated datasets such as \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\), their performance often drops significantly.

It must be noted that the number of entries in solubility datasets remains limited (approximately 700 for \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\) and only a few hundreds for other datasets used in the literature to train models), which hinders the development of sufficiently robust methods and limits the possibility of avoiding overfitting. Moreover, most methods do not predict the change in solubility \(\Delta S\) but rather the solubility S of the input sequence, a slightly different problem that makes predicting changes in solubility more challenging for them. Indeed, almost half of the predictors mentioned above do not show a statistically significant correlation with \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\) values and are thus not reported in Table 4. The last three methods tested, ESM-1v, SaProt, and PoPMuSiC—predict changes in fitness (the first two) and thermodynamic stability upon mutation (the latter), which are only partially related to solubility. Despite this, their correlation of 0.3 is surprisingly among the highest after SOuLMuSiC’s correlation, indicating a close relationship of their descriptors with solubility.

Test on reverse mutations and antisymmetry properties

To test SOuLMuSiC’s antisymmetry properties, we evaluated it on the dataset of reverse mutations, \(\mathcal {D}_{Inv}\). If the change in protein solubility due to a mutation from protein “wt” to protein “mut” is given by Eq. 1, the reverse mutation from protein “mut” to protein “wt” should, by construction, satisfy

This antisymmetry property has already been thoroughly studied and discussed in the field of predicting changes in protein stability and protein-protein binding affinity upon mutations43,69,70.

To quantify how much the predictions deviate from perfect antisymmetric behavior, we introduced two measures43. The first, \(r_{dir,inv}\), is the Pearson correlation coefficient between the predictions on the datasets of direct and reverse mutations, which is equal to \(-1\) for a perfectly antisymmetric predictor. The second score, \(\langle \delta \rangle\), is defined as:

where the sum is over all N mutations of the dataset considered. For a perfectly antisymmetric predictor, \(\langle \delta \rangle\) is equal to 0.

We evaluated SOuLMuSiC and its features on the datasets of direct and reverse mutations \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\) and \(\mathcal {D}_{Inv}\). Table 5 provides the values of the two metrics \(\langle \delta \rangle\) and \(r_{dir,inv}\), along with \(\rho _{dir}\) and \(\rho _{inv}\), the Spearman correlation coefficients between predicted and experimental values on these two datasets. SOuLMuSiC shows rather good performance in terms of antisymmetry with \(r_{dir,inv}=-0.90\) and \(\langle \delta \rangle = -0.37\). Indeed, \(r_{dir,inv}\) is rather close to the expected value of \(-1\) and \(\langle \delta \rangle\) is small compared to the standard deviation of the predicted score distributions, which is in the 0.8-0.9 range for \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\) and \(\mathcal {D}_{Inv}\). The Spearman correlation coefficients \(\rho _{dir}\) and \(\rho _{inv}\) of SOuLMuSiC predictions for \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\) and \(\mathcal {D}_{Inv}\) are also good, although somewhat better for the direct mutation set than for the reverse mutation set, with values of 0.56 and 0.49, respectively.

To better understand where the deviation from an antisymmetric behavior comes from, we analyzed the properties of each of the nine components of SOuLMuSiC. The features defined from amino-acid scales are perfectly symmetric but correlate poorly with experimental data (\(\rho _{dir}\) and \(\rho _{inv}\) between 0.1 and 0.2). The statistical potentials are almost symmetric in terms of \(\langle \delta \rangle\). They are, however, not totally symmetric in terms of \(r_{inv,dir}\), because they incorporate some inaccuracies in the statistical potential derivation and because the mutated structures are modeled rather than experimental. In contrast, the pLM feature has good antisymmetry properties in terms of \(r_{inv,dir}\), but not at all in terms of \(\langle \delta \rangle\). It is biased toward negative values, which means that neutral mutations are not defined by a score of 0. Both the statistical potentials and pLM correlate significantly better with experimental data than amino-acid scales on both direct and reverse mutations. Indeed, \(\rho _{dir}\) and \(\rho _{inv}\) are between 0.2 and 0.3 for all statistical potentials except the “std” potential, and are equal to 0.3 for pLM.

Application to LGK and trade-off between solubility and stability

As an additional test of SOuLMuSiC, we studied the solubility of Levoglucosan kinase (LGK) from Lipomyces starkeyi, an enzyme that catalyzes the phosphorylation of levoglucosan45. In more detail, we analyzed the interplay between protein solubility and stability, which generally exhibits a trade-off71. In general, increasing thermodynamic stability of proteins tends to reduce their aggregation propensities and make them more soluble, but there are examples of proteins with enhanced stability and reduced solubility72.

To analyze this trade-off, we applied our SOuLMuSiC predictor, along with PoPMuSiC50, the tool we previously developed to predict the impact of mutations on thermodynamic stability. We compared these predictions with deep mutagenesis scanning data where the effects of amino-acid substitutions on a combination of protein solubility and stability were systematically explored using yeast surface display (YSD)46. Solubility and stability are challenging to disentangle in high-throughput data, and that is why the YSD experiment considered measures a combination of both.

The results of the comparison are shown in Table 6. We first compared the results of the SOuLMuSiC and PoPMuSiC scores with the experimental YSD scores46, and found good Spearman correlation coefficients of \(\rho =0.36\) and \(\rho =-0.29\), respectively. Note that the solvent accessibility has also a good Spearman correlation of 0.30, which indicates the tendency of mutations in the protein core to have a larger impact than those at the surface. Note that this trend is, as expected, more marked for stability73 than for solubility.

Since the experimental YSD score reflects a mixture of the two quantities, stability and solubility, we combined our prediction scores in the following way:

where \(\text {PoP}\) and \(\text {SOuL}\) are the PoPMuSiC \(\Delta \Delta G\) value and the SOuLMuSiC score, respectively, and \(\sigma _P\) and \(\sigma _S\), their respective root mean square deviations on the LGK dataset. Note the minus sign between the two terms. Indeed, variants that increase stability (with a negative \(\Delta \Delta G\) in our conventions) are likely to also increase solubility, resulting in a positive SOuL score. As the YSD score arises from a combination of solubility and stability, we observe that the combined SOuLMuSiC and PoPMuSiC predictions perform better than each individually, reaching the correlation \(\rho =0.40\).

Note that solubility and stability are mildly correlated: the Spearman correlation coefficient between the SOuL scores and PoPMuSiC’s \(\Delta \Delta G\) values is equal to \(\rho =-0.31\) on the LGK dataset. We already observed a similar trend on the \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\) dataset (Table 4).

It is well known that mutations near the catalytic site are likely to disrupt enzyme activity but are often stabilizing74. To study the catalytic site in more detail, we analyzed the prediction scores for all possible mutations of residues located within a distance of less than 6 Å from the center of the catalytic site and compared them with those further away. We found that mutations in the catalytic site have an average \(\Delta \Delta G\) value of 0.47 kcal/mol, which is lower than the 1.20 kcal/mol observed for other residues, suggesting that these regions are inherently less impacted in terms of stability74. For solubility, however, there is essentially no difference, with the average score for residues close to and far from the catalytic site being equal to about −1.0.

Application to aggregation-prone proteins

Protein aggregation is a well-studied yet poorly understood phenomenon that leads to a series of pathological conditions75,76. A series of proteins end up in misfolded states that can trigger the formation of supramolecular assemblies such as amyloid fibrils. These insoluble assemblies are often observed as deposits in major neurodegenerative diseases: for example, the aggregation of \(\alpha\)-synuclein is considered as one of the hallmarks of Parkinson’s disease, the formation of amyloid beta (A\(\beta\)) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles composed of the Tau protein is strongly involved in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease, and Huntingtin fibrils are the toxic species involved in Huntington’s disease. Although amyloid formation and protein solubility are distinct phenomena, they are interrelated32,77. Thus, we evaluated our SOuLMuSiC predictor on its ability to predict the effects of variants on aggregation-prone proteins.

Aggregation-prone proteins are often characterized by flexible and intrinsically disordered regions, making it difficult to obtain high-quality structures of their folded form78. However, obtaining the structure of amyloid fibrils is comparatively easier and indeed, hundreds of them can be found in the PDB.

To study protein aggregation propensities, we applied SOuLMuSiC to the A\(\beta\)−42 protein, using both the amyloid fibril structure and the protein-in-solution structure as input. When the input structure is an insoluble aggregate, we set the parameter \(\beta\) in front of the structural terms in our model to \(\beta = -1\) (see Eq. 6). In contrast, SOuLMuSiC applied to folded proteins in solution uses \(\beta = 1\). This adjustment is thermodynamically intuitive: stabilizing the native globular form of a protein generally leads to increased solubility, while stabilizing an insoluble form, such as a fibril, further decreases the solubility of the assembly.

We applied SOuLMuSiC to the structure of the A\(\beta\)−42 fibrils identified with the PDB code 2NAO79 and to the structure of the in-solution A\(\beta\)−42 protein identified with the code 1IYT80. Note that both the 2NAO and 1IYT structures were derived from nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) data; we used as SOuLMuSiC scores the average of the scores on all 10 NMR structures in the PDB files. We then compared these scores with the solubility data47 derived from a yeast aggregation assay combined with deep mutational scanning. We focused on single amino-acid substitutions, excluding truncating and synonymous mutations, which amounts to a total of 790 mutations. We plotted the predicted scores versus the experimental values in Figure 2.

As shown in the figure, the predicted \(\Delta S^{SOuL}\) values are well correlated with the experimental \(\Delta S^{exp}\) values, with Spearman correlation coefficients of \(\rho =0.57\) and 0.62 for the 2NAO and 1IYT structures, respectively. The \(\beta\) parameter (in Eq. 6) is set to −1 for the fibril structure 2NAO and to +1 for the solution structure 1IYT. Interestingly, exchanging the \(\beta\) values results in a drastic drop in performance, with Spearman correlation \(\rho\) decreasing to around 0.2. Also note that the correlation between predictions obtained with the two structures is high with a Pearson correlation coefficient \(r=0.84\), although they have completely different conformations.

Webserver

To make SOuLMuSiC accessible to the broad academic community, we made it available through the webserver http://babylone.3bio.ulb.ac.be/SOuLMuSiC/. The SOuLMuSiC webserver version is the one trained on the entire \(\mathcal {D}_{Sol}\) dataset. As SOuLMuSiC is structure-based, users must provide a 3D structure of the target protein as input. The user has the choice among three different methods for this: provide the PDB code40 whose structure will be automatically retrieved from the PDB; the UniProt ID, in which case the corresponding structure will be retrieved from AlphaFold DB81; or upload his own structure in PDB format. Note that SOuLMuSiC takes into account all chains contained in the submitted structure file when computing the solubility score upon mutations, so users should provide only the chains of interest. The user also has to choose whether the provided structure is a globular protein or a insoluble macromolecular assembly.

Once the structure is submitted, the computation starts. SOuLMuSiC is very fast and performs the prediction of solubility for all single-site mutations in a protein in less than a minute. Upon completion of the calculation, a CSV file containing the results is sent to the email address provided upon submission. The result file contains, for all single-site mutations in all chains of the submitted protein structure, the solvent accessibility of the mutated residue and the \(\Delta S^{SOuL}\) value.

Discussion

The optimization of protein solubility is one of the fundamental goals in any biotechnological process involving proteins. Despite considerable efforts over the last decades, it is still difficult to determine, whether experimentally or computationally, the impact of mutations on protein solubility. In this article, we have taken a step towards this goal by presenting SOuLMuSiC, our tool of the MuSiC suite50,65,82,83,84 dedicated to predict the effect of single-site mutations on protein solubility. Our tool outperforms state-of-the-art approaches when tested on a highly curated dataset of mutations manually collected from the literature and has also been successfully validated on external datasets to assess the generalizability of our approach.

Additional aspects should be explored to further improve our approach. The development of accurate solubility predictors is hindered by the limited availability of mutational data on solubility. Expanding the dataset in the near future could facilitate the training of more complex models with a larger number of features and parameters. Deep mutagenesis data are certainly helpful, though their precise link to protein solubility is complex; solubility, while related to stability and aggregation, is a distinct property, and disentangling these factors is challenging, as we observed in the Results section. Another issue is related to data variability, since solubility measurements are performed using various experimental setups. Even though we made efforts to standardize all collected information in constructing our dataset, this variability remains a source of noise. Finally, the impact of environmental variables, such as pH or temperature, plays a significant role in protein solubility. These factors are not currently taken into account in SOuLMuSiC, and incorporating them could improve its performance.

Although SOuLMuSiC can still be optimized, its current version already achieves good performance and can be used to rationally design new proteins with improved solubility. Given the significant challenges that solubility issues present in both academic and industrial processes, we are confident that SOuLMuSiC will be of great interest to the scientific community and could help optimize a wide variety of biotechnological processes.

Data availability

The curated datasets used to train and test our models, as well as all PDB structures analyzed, are available in our GitHub repository: github.com/3BioCompBio/SOuLMuSiC.

References

Castro, Filipa, & Ferreira, Joana. Advances in protein solubility and thermodynamics: quantification, instrumentation, and perspectives. CrystEngComm, (2023).

Kramer, Ryan M., Shende, Varad R., Motl, Nicole, Pace, C Nick & Scholtz, J Martin. Toward a molecular understanding of protein solubility: increased negative surface charge correlates with increased solubility. Biophysical journal 102(8), 1907–1915 (2012).

Vihinen, Mauno. Solubility of proteins. ADMET and DMPK 8(4), 391–399 (2020).

Shire, Steven J., Shahrokh, Zahra & Liu, J. U. N. Challenges in the development of high protein concentration formulations. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences 93(6), 1390–1402 (2004).

Jiskoot, Wim, Hawe, Andrea, Menzen, Tim, Volkin, David B. & Crommelin, Daan JA. Ongoing challenges to develop high concentration monoclonal antibody-based formulations for subcutaneous administration: Quo vadis?. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 111(4), 861–867 (2022).

Correa, Agustín & Oppezzo, Pablo. Overcoming the solubility problem in e. coli: available approaches for recombinant protein production. Insoluble Proteins: Methods and Protocols, pages 27–44, (2015).

Pouresmaeil, Mahin & Azizi-Dargahlou, Shahnam. Factors involved in heterologous expression of proteins in e. coli host. Archives of Microbiology 205(5), 212 (2023).

Haass, Christian & Selkoe, Dennis J. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the alzheimer’s amyloid β-peptide. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 8(2), 101–112 (2007).

Hijaz, Baraa A. & Volpicelli-Daley, Laura A. Initiation and propagation of α-synuclein aggregation in the nervous system. Molecular neurodegeneration 15, 1–12 (2020).

Vendra, Venkata Pulla Rao., Khan, Ismail, Chandani, Sushil, Muniyandi, Anbukkarasi & Balasubramanian, Dorairajan. Gamma crystallins of the human eye lens. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-General Subjects 1860(1), 333–343 (2016).

Boatz, Jennifer C., Whitley, Matthew J., Li, Mingyue, Gronenborn, Angela M. & Wel, Patrick CA van der. Cataract-associated p23t γd-crystallin retains a native-like fold in amorphous-looking aggregates formed at physiological ph. Nature Communications 8(1), 15137 (2017).

Mukherjee, Abhisek, Morales-Scheihing, Diego, Butler, Peter C. & Soto, Claudio. Type 2 diabetes as a protein misfolding disease. Trends in molecular medicine 21(7), 439–449 (2015).

Goedert, Michel, Clavaguera, Florence & Tolnay, Markus. The propagation of prion-like protein inclusions in neurodegenerative diseases. Trends in neurosciences 33(7), 317–325 (2010).

Hou, Qingzhen, Bourgeas, Raphaël, Pucci, Fabrizio & Rooman, Marianne. Computational analysis of the amino acid interactions that promote or decrease protein solubility. Scientific reports 8(1), 14661 (2018).

Bhandari, Bikash K., Gardner, Paul P. & Lim, Chun Shen. Solubility-weighted index: fast and accurate prediction of protein solubility. Bioinformatics 36(18), 4691–4698 (2020).

Warwicker, Jim, Charonis, Spyros & Curtis, Robin A. Lysine and arginine content of proteins: computational analysis suggests a new tool for solubility design. Molecular pharmaceutics 11(1), 294–303 (2014).

Chan, Pedro, Curtis, Robin A. & Warwicker, Jim. Soluble expression of proteins correlates with a lack of positively-charged surface. Scientific reports 3(1), 3333 (2013).

Esposito, Dominic & Chatterjee, Deb K. Enhancement of soluble protein expression through the use of fusion tags. Current opinion in biotechnology 17(4), 353–358 (2006).

Surinder Mohan Singh and Amulya Kumar Panda. Solubilization and refolding of bacterial inclusion body proteins. Journal of bioscience and bioengineering 99(4), 303–310 (2005).

Luis Felipe Vallejo and Ursula Rinas. Strategies for the recovery of active proteins through refolding of bacterial inclusion body proteins. Microbial cell factories 3, 1–12 (2004).

Singh, Anupam, Upadhyay, Vaibhav, Upadhyay, Arun Kumar, Singh, Surinder Mohan & Panda, Amulya Kumar. Protein recovery from inclusion bodies of escherichia coli using mild solubilization process. Microbial cell factories 14, 1–10 (2015).

Silva, Filipe SR. et al. In vivo cleavage of solubility tags as a tool to enhance the levels of soluble recombinant proteins in escherichia coli. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 118(11), 4159–4167 (2021).

Niwa, Tatsuya et al. Bimodal protein solubility distribution revealed by an aggregation analysis of the entire ensemble of escherichia coli proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106(11), 4201–4206 (2009).

Magnan, Christophe N. & Randall, Arlo. Solpro: accurate sequence-based prediction of protein solubility. Bioinformatics 25(17), 2200–2207 (2009).

Agostini, Federico, Cirillo, Davide, Livi, Carmen Maria, Delli Ponti, Riccardo & Tartaglia, Gian Gaetano. cc sol omics: A webserver for solubility prediction of endogenous and heterologous expression in escherichia coli. Bioinformatics 30(20), 2975–2977 (2014).

Hebditch, Max, Carballo-Amador, M Alejandro, Charonis, Spyros, Curtis, Robin & Warwicker, Jim. Protein–sol: a web tool for predicting protein solubility from sequence. Bioinformatics 33(19), 3098–3100 (2017).

Hou, Qingzhen, Kwasigroch, Jean Marc, Rooman, Marianne & Pucci, Fabrizio. SOLart: a structure-based method to predict protein solubility and aggregation. Bioinformatics 36(5), 1445–1452 (2020).

Hon, Jiri et al. Soluprot: prediction of soluble protein expression in escherichia coli. Bioinformatics 37(1), 23–28 (2021).

Raimondi, Daniele, Orlando, Gabriele, Fariselli, Piero & Moreau, Yves. Insight into the protein solubility driving forces with neural attention. PLoS computational biology 16(4), e1007722 (2020).

Thumuluri, Vineet, Martiny, Hannah-Marie., Almagro Armenteros, Jose J., Salomon, Jesper & Nielsen, Henrik. Netsolp: predicting protein solubility in escherichia coli using language models. Bioinformatics 38(4), 941–946 (2022).

Veleckỳ, Jan et al. Soluprotmutdb: A manually curated database of protein solubility changes upon mutations. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 20, 6339–6347 (2022).

Sormanni, Pietro, Aprile, Francesco A. & Vendruscolo, Michele. The CamSol method of rational design of protein mutants with enhanced solubility. Journal of Molecular Biology 427(2), 478–490 (2015).

Paladin, Lisanna, Piovesan, Damiano & Tosatto, Silvio CE. SODA: prediction of protein solubility from disorder and aggregation propensity. Nucleic Acids Research 45(W1), W236–W240 (2017).

Yang, Yang, Zeng, Lianjie & Vihinen, Mauno. PON-Sol2: Prediction of effects of variants on protein solubility. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22(15), 8027 (2021).

Ferreira, Joana & Castro, Filipa. Advances in protein solubility and thermodynamics: quantification, instrumentation, and perspectives. CrystEngComm 25(46), 6388–6404 (2023).

Trevino, Saul R., Scholtz, J Martin & Pace, C Nick. Measuring and increasing protein solubility. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences 97(10), 4155–4166 (2008).

Oeller, Marc et al. Sequence-based prediction of ph-dependent protein solubility using camsol. Briefings in Bioinformatics 24(2), bbad004 (2023).

Chrunyk, B. A., Evans, J., Lillquist, J., Young, P. & Wetzel, R. Inclusion body formation and protein stability in sequence variants of interleukin-1 beta. Journal of Biological Chemistry 268(24), 18053–18061 (1993).

Mirarefi, Amir Y. & Zukoski, Charles F. Gradient diffusion and protein solubility: use of dynamic light scattering to localize crystallization conditions. Journal of crystal growth 265(1–2), 274–283 (2004).

Berman, Helen M. et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Research 28(1), 235–242 (2000).

Jumper, John et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with alphafold. Nature 596(7873), 583–589 (2021).

Waterhouse, Andrew et al. Swiss-model: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic acids research 46(W1), W296–W303 (2018).

Pucci, Fabrizio et al. Quantification of biases in predictions of protein stability changes upon mutations. Bioinformatics 34(21), 3659–3665 (2018).

Fiser, András & Šali, Andrej. Modeller: generation and refinement of homology-based protein structure models. In Methods in enzymology, volume 374, pages 461–491. Elsevier, (2003).

Rother, Christina et al. Biochemical characterization and mechanistic analysis of the levoglucosan kinase from lipomyces starkeyi. ChemBioChem 19(6), 596–603 (2018).

Klesmith, Justin R., Bacik, John-Paul., Wrenbeck, Emily E., Michalczyk, Ryszard & Whitehead, Timothy A. Trade-offs between enzyme fitness and solubility illuminated by deep mutational scanning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114(9), 2265–2270 (2017).

Gray, Vanessa E. et al. Elucidating the molecular determinants of aβ aggregation with deep mutational scanning. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics 9(11), 3683–3689 (2019).

Miyazawa, Sanzo & Jernigan, Robert L. Residue–residue potentials with a favorable contact pair term and an unfavorable high packing density term, for simulation and threading. Journal of molecular biology 256(3), 623–644 (1996).

Dehouck, Yves, Gilis, Dimitri & Rooman, Marianne. A new generation of statistical potentials for proteins. Biophysical journal 90(11), 4010–4017 (2006).

Dehouck, Yves, Kwasigroch, Jean Marc, Gilis, Dimitri & Rooman, Marianne. PoPMuSiC 2.1: a web server for the estimation of protein stability changes upon mutation and sequence optimality.. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 1–12 (2011).

Hou, Qingzhen et al. Swotein: a structure-based approach to predict stability strengths and weaknesses of proteins. Bioinformatics 37(14), 1963–1971 (2021).

Dalkas, Georgios A., Teheux, Fabian, Kwasigroch, Jean Marc & Rooman, Marianne. Cation–π, amino–π, π–π, and h-bond interactions stabilize antigen–antibody interfaces. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 82(9), 1734–1746 (2014).

Rooman, Marianne J., Kocher, Jean-Pierre A. & Wodak, Shoshana J. Prediction of protein backbone conformation based on seven structure assignments: influence of local interactions. Journal of molecular biology 221(3), 961–979 (1991).

Kocher, Jean-Pierre A., Rooman, Marianne J. & Wodak, Shoshana J. Factors influencing the ability of knowledge-based potentials to identify native sequence-structure matches. Journal of molecular biology 235(5), 1598–1613 (1994).

Wimley, William C. & White, Stephen H. Experimentally determined hydrophobicity scale for proteins at membrane interfaces. Nature structural biology 3(10), 842–848 (1996).

Kyte, Jack & Doolittle, Russell F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. Journal of molecular biology 157(1), 105–132 (1982).

Janin, J. O. E. L. Surface and inside volumes in globular proteins. Nature 277(5696), 491–492 (1979).

Tanford, Charles. Physical chemistry of macromolecules (John Wiley & Sons, 1966).

Shaw, Kevin L., Grimsley, Gerald R., Yakovlev, Gennady I., Makarov, Alexander A. & Pace, C Nick. The effect of net charge on the solubility, activity, and stability of ribonuclease sa. Protein Science 10(6), 1206–1215 (2001).

Chou, Kuo-Chen. Using amphiphilic pseudo amino acid composition to predict enzyme subfamily classes. Bioinformatics 21(1), 10–19 (2005).

Xiao, Nan, Cao, Dong-Sheng., Zhu, Min-Feng. & Qing-Song, Xu. protr/protrweb: R package and web server for generating various numerical representation schemes of protein sequences. Bioinformatics 31(11), 1857–1859 (2015).

Meier, Joshua et al. Language models enable zero-shot prediction of the effects of mutations on protein function. Advances in neural information processing systems 34, 29287–29303 (2021).

Suzek, Baris E., Huang, Hongzhan, McGarvey, Peter, Mazumder, Raja & Wu, Cathy H. UniRef: comprehensive and non-redundant uniprot reference clusters. Bioinformatics 23(10), 1282–1288 (2007).

Bepler, Tristan & Berger, Bonnie. Learning the protein language: Evolution, structure, and function. Cell systems 12(6), 654–669 (2021).

Pucci, Fabrizio, Bourgeas, Raphaël & Rooman, Marianne. Predicting protein thermal stability changes upon point mutations using statistical potentials: Introducing hotmusic. Scientific reports 6(1), 23257 (2016).

Gilis, Dimitri & Rooman, Marianne. Predicting protein stability changes upon mutation using database-derived potentials: solvent accessibility determines the importance of local versus non-local interactions along the sequence. Journal of molecular biology 272(2), 276–290 (1997).

Wolfram Research, Inc. Mathematica, Version 14.0. URL https://www.wolfram.com/mathematica. Champaign, IL, (2024).

Su, Jin, Han, Chenchen, Zhou, Yuyang, Shan, Junjie, Zhou, Xibin & Yuan, Fajie. SaProt: Protein language modeling with structure-aware vocabulary. bioRxiv, pages 2023–10, (2023).

Usmanova, Dinara R. et al. Self-consistency test reveals systematic bias in programs for prediction change of stability upon mutation. Bioinformatics 34(21), 3653–3658 (2018).

Tsishyn, Matsvei, Pucci, Fabrizio & Rooman, Marianne. Quantification of biases in predictions of protein–protein binding affinity changes upon mutations. Briefings in bioinformatics, 25(1): bbad491, (2024a).

molecules defined by their trade-offs. Lavi S Bigman and Yaakov Levy. Proteins. Current opinion in structural biology 60, 50–56 (2020).

Broom, Aron, Jacobi, Zachary, Trainor, Kyle & Meiering, Elizabeth M. Computational tools help improve protein stability but with a solubility tradeoff.. Journal of Biological Chemistry 292(35), 14349–14361 (2017).

Hermans, Pauline, Tsishyn, Matsvei, Schwersensky, Martin, Rooman, Marianne & Pucci, Fabrizio. Exploring evolution to uncover insights into protein mutational stability. Molecular Biology and Evolution, page msae267, (2024).

Hou, Qingzhen, Rooman, Marianne & Pucci, Fabrizio. Enzyme stability-activity trade-off: new insights from protein stability weaknesses and evolutionary conservation. Journal of chemical theory and computation 19(12), 3664–3671 (2023).

Chiti, Fabrizio & Dobson, Christopher M. Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem 75(1), 333–366 (2006).

Louros, Nikolaos, Schymkowitz, Joost & Rousseau, Frederic. Mechanisms and pathology of protein misfolding and aggregation. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 24(12), 912–933 (2023).

Agostini, Federico, Vendruscolo, Michele & Tartaglia, Gian Gaetano. Sequence-based prediction of protein solubility. Journal of molecular biology 421(2–3), 237–241 (2012).

Dyson, H Jane & Wright, Peter E. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 6(3), 197–208 (2005).

Wälti, Marielle Aulikki et al. Atomic-resolution structure of a disease-relevant aβ (1–42) amyloid fibril. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113(34), E4976–E4984 (2016).

Crescenzi, Orlando et al. Solution structure of the alzheimer amyloid β-peptide (1–42) in an apolar microenvironment: Similarity with a virus fusion domain. European journal of biochemistry 269(22), 5642–5648 (2002).

Varadi, Mihaly et al. AlphaFold protein structure database in 2024: providing structure coverage for over 214 million protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Research 52(D1), D368–D375 (2024).

Dehouck, Yves, Kwasigroch, Jean Marc, Rooman, Marianne & Gilis, Dimitri. BeAtMuSiC: prediction of changes in protein-protein binding affinity on mutations. Nucleic Acids Research 41(W1), W333–W339 (2013).

Ancien, François, Pucci, Fabrizio, Godfroid, Maxime & Rooman, Marianne. Prediction and interpretation of deleterious coding variants in terms of protein structural stability. Scientific reports 8(1), 4480 (2018).

Tsishyn, Matsvei et al. Fitmusic: leveraging structural and (co) evolutionary data for protein fitness prediction. Human genomics 18(1), 36 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the Belgian Fund for Scientific Research (F.R.S.-FNRS) through a PDR project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A. (Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing original draft, Writing review & editing), J.K. (Validation, Software, Writing review & editing), M.R (Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing original draft, Writing review & editing) and F.P (Investigation, Methodology, Software, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing original draft, Writing review & editing)

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.βαγπ

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Attanasio, S., Kwasigroch, J., Rooman, M. et al. SOuLMuSiC, a novel tool for predicting the impact of mutations on protein solubility. Sci Rep 15, 27531 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11326-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11326-x