Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the accuracy of six intraocular lens (IOL) calculation formulas using total keratometry (TK) and standard keratometry (K) measurements from the IOLMaster 700 in various ocular subgroups. A total of 212 eyes were analyzed. The mean absolute error (MAE), standard deviation (SD) of prediction error, and the median absolute error (MedAE) were calculated for each formula. and the prediction accuracy was compared across different subgroups categorized by axial length (AL), anterior chamber depth (ACD), lens thickness (LT), and other ocular parameters. Results showed that the Barrett Universal II (BU II) formula consistently had the lowest MAEs and MedAEs in the overall sample and most subgroups. The BU II formula performed particularly well in subgroups with thin LT when using TK mode and in medium LT subgroups using K mode. Comparison between TK and K modes showed no consistent superiority, with each mode outperforming the other in specific subgroups. The accuracy of the BU II formula was not influenced by ocular parameters, suggesting its robustness across different patient groups. In conclusion, the BU II formula demonstrated superior accuracy compared to other formulas, especially in specific subgroups, and its performance remained consistent regardless of ocular measurement variations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intraocular lens (IOL) cataract surgery implantation is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures. Cataract surgery is not only an extraction technique but also has become a refractive treatment1,2. The demand for excellent post-operative visual and refractive outcomes from patients is increasing. The improvement of the refractive outcomes of cataract surgery needs advanced optical biometry measurement and accurate IOL power calculation formulas. Advanced optical biometry measurement technologies such as partial coherence interferometry, optical low-coherence reflectometry, and swept-source optical coherence tomography (SS-OCT) have increased the precision of biometric measurements3,4. The IOLMaster 700 is a widely used biometry device that uses SS-OCT to produce measurements of optical biometry parameters. This new biometric instrument is faster and more sensitive in measurement compared to its predecessor, the IOLMaster 5005. Those measurements affect the accuracy of modern IOL power calculation formulas, which aim to improve the accuracy of their predictions of effective lens position (ELP). Keratometry (K) value is one of the foundational variables in all IOL power calculation formulas. Standard K value is based only on the anterior corneal surface measurement. Posterior corneal refractive power also influences the total corneal refractive power. The combination of anterior and posterior corneal curvatures, along with corneal thickness, contributes to the eye’s total refractive power6. Total Keratometry (TK) is an innovative measurement that integrates telecentric keratometry and SS-OCT to assess both anterior and posterior corneal surfaces, now included in the IOLMaster 7005,7. This method, along with standard K, is utilized in research evaluating IOL power calculation formulas for eyes undergoing IOL implantation6,8,9,10. Axial length (AL) is another primary variable in traditional IOL formulas such as Hoffer Q, Holladay 1, and SRK/T. Modern formulas incorporate additional biometric parameters beyond AL and K. For example, Haigis uses preoperative anterior chamber depth (ACD) along with AL and K; Holladay 2 incorporates ACD, lens thickness (LT), WTW, preoperative refraction, and age; and Barrett Universal II (BU II) includes AL, ACD, LT, K, and horizontal white-to-white (WTW) distance to improve predictive accuracy. Research indicates that the BU II formula provides better predictability in refractive outcomes than other formulas4,11,12,13, and is now integrated into the IOLMaster 700.

How to choose the best IOL calculation formula or keratometry method based on a patient’s varied preoperative measurement parameters still merits further research. It is also worth researching whether different preoperative measurement parameters or keratometry methods affect the predictive accuracy of IOL calculation formulas. Therefore, our study is aimed to analyze the performance of current IOL power calculation formulas across various subgroups. These subgroups are categorized into low, medium, and high based on preoperative parameters measured by the IOLMaster 700, including AL, ACD, LT, WTW, and K values. Within each subgroup, both TK and K modes are utilized to calculate the predicted refractive outcomes using different IOL formulas. The study subsequently compares the predictive accuracy of these formulas within each subgroup, thereby providing a detailed assessment of their performance.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (ID 2023-0013). All procedures adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. A retrospective chart review consisting of 212 cataract patients (212 eyes) who underwent uneventful single focus PCIOL Hoya iSert® 250 (Hoya Surgical Optics, Inc., Singapore) implantation between September 2020 and March 2022 was performed. The study followed the previously reported protocol to compare the accuracy of IOL formulas14. Patients were excluded if they had corneal opacity, pterygium, glaucoma, uveitis, severe dry eye, retinopathy, lens subluxation, severe systemic diseases, operation-related complications, and postoperative best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) worse than 20/40. For patients with bilateral cataract surgery, one eye was randomly selected. All patients underwent standard cataract phacoemulsification (2.0 mm transparent corneal incision, approximately 5.2 mm continuous circular capsulorhexis, no sutures) performed by a single experienced surgeon (W.X.). Postoperative follow-up was conducted for all patients over a period of 3 months. For analysis, refractive data obtained at 1 month postoperatively were used. Manifest refraction was performed under a standard 5-meter lane length. Eyes presenting with postoperative corneal edema, abnormal intraocular pressure, or retinal pathology were excluded to ensure data reliability and consistency.

Biometry and IOL power calculation

Preoperative measurements, including AL, ACD, LT, WTW, average K value, average TK value, corneal astigmatism (ΔK) value, and total corneal astigmatism (ΔTK) value, were obtained with the IOLMaster 700 (Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany). To ensure measurement standardization and consistency, all biometric evaluations were performed by a single experienced examiner using the IOLMaster 700. Prior to each measurement, patients were instructed to blink several times to promote a uniform tear film. Measurements were only accepted if all parameter indicators on the device were displayed in green, indicating high-quality and reliable data. IOL power was calculated using the device’s integrated software (version 1.88.1.64861) with optimized constants from the User Group for Laser Interference Biometry (ULIB)15. Calculations were performed using both TK and K values across the BU II, SRK/T, Haigis, Hoffer Q, Holladay 1, and Holladay 2 formulas. The constants used were as follows: lens factor for BU II = 1.62; Haigis a0 = − 0.542, a1 = 0.161, a2 = 0.204; Holladay 1 surgeon factor = 1.52; Hoffer Q pACD = 5.30; and SRK/T A-constant = 118.50. Prediction error (PE) was defined as the difference between the postoperative spherical equivalent refraction and the predicted refraction for each eye. The mean absolute error (MAE) was calculated as the arithmetic mean of the absolute PE values across all cases, while the median absolute error (MedAE) was defined as the median of those absolute values. Refractive accuracy was assessed using MAE, MedAE, and standard deviation (SD) of PE. In accordance with established protocols for evaluating IOL formula performance, MedAE was selected as the primary metric for inter-formula statistical comparisons14,16,17. This is because absolute errors do not follow a Gaussian distribution and the MAE is particularly sensitive to outliers, which may skew results. In contrast, the MedAE better represents the central tendency of the absolute PE and is less affected by extreme values. Therefore, to provide a comprehensive evaluation of each formula’s performance and to ensure consistency with prior publications, we report MAE, MedAE, and SD across all formulas, and proportion of eyes with PE within ± 0.25 D, ± 0.50 D, ± 0.75 D, and ± 1.00 D was calculated to evaluate the refractive outcomes of each formula.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 26.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Friedman test of the MedAE with Wilcoxon signed rank post hoc analyses and Bonferroni correction was used to analyze and compare the accuracies of the six formulas. The Wilcoxon test of the MedAE was used to compare the accuracy of each formula using TK or K mode. Cochran’s Q test with Dunn’s post-hoc test was used to compare the percentage of eyes within a certain range of PE between the six formulas. The McNemar’s test was performed to compare the percentage of eyes within a certain range of PE between each formula using TK or K mode. Backward stepwise multivariate linear regression was performed to investigate the associations between PE and preoperative biometric variables, including AL, ACD, LT, average K, average TK, ΔK, ΔTK, age, sex, laterality, and WTW. Multicollinearity analysis was used to assess the independence of each predictor variable in the regression model. Although not all parameters are utilized by each IOL formula, this analysis aimed to identify independent predictors of refractive accuracy across the dataset. PE was analyzed separately for each formula. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Result

Table 1 shows the general information and mean values of the parameters measured by the iolmaster 700 for 212 patients undergoing IOL implantation.

Refractive PEs of the study cohort

Comparison of six formulas in entire sample are shown in Table 2; Fig. 1. In TK mode, significant MedAE variations were observed across formulas (P = 0.000), with BU II-TK achieving the lowest MedAE, surpassing SRK/T-TK (P = 0.018), Holladay 2-TK (P = 0.008), Haigis-TK (P = 0.001), Hoffer Q-TK (P = 0.000), and Holladay 1-TK (P = 0.000). K mode analyses showed similar results (P = 0.000), with BU II-K recording the lowest MedAE, significantly less than SRK/T-K (P = 0.000), Holladay 2-K (P = 0.002), Haigis-K (P = 0.006), Hoffer Q-K (P = 0.000), and Holladay 1-K (P = 0.000). Additionally, BU II (P = 0.035) and Hoffer Q (P = P = 0.017) formulas had lower MedAEs in K mode compared to TK mode. Detailed pairwise comparisons for other significant differences are presented in Table 2 and the associated footnotes.

Percentage of eyes with a PE within ± 0.25, ± 0.50, ± 0.75, and ± 1.00 D

Table 3 and Fig. 2 show the percentage of eyes within the diopter range indicated for each formula. In the analysis of the entire sample, no statistically significant differences were found among the formulas for the percentage of eyes with a PE within ± 0.25 D under the TK mode (P = 0.184). Similarly, no significant differences were observed among formulas for PEs within ± 1.00 D under both TK (P = 0.133) And K (P = 0.101) modes. However, statistically significant differences in the percentages of eyes were noted among formulas for PEs within ± 0.25 D in K (P = 0.032) mode, ± 0.50 D in both TK (P = 0.000) And K (P = 0.000) modes, And ± 0.75 D in both TK (P = 0.000) And K (P = 0.001) modes, with the BU II formula exhibiting the highest percentages. Notably, within a PE of ± 0.75 D, the proportions of eyes for Haigis-TK, hoffer Q-TK, And holladay 2-TK were lower than those for Haigis-K (P = 0.016), hoffer Q-K (P = 0.039), And holladay 2-K (P = 0.001) formulas, respectively. For other statistically significant differences among formulas, pairwise comparison results are detailed in Tables 3 And the corresponding footnotes below.

Subgroup analysis with different AL, ACD, LT and WTW values

Table 4 Shows the maes, SDs and medaes.calculated using the six formulas for the three AL subgroups. For the subgroup within the al > 26 mm (n = 46), significant differences in medaes.were observed across the formulas in both TK (P = 0.000) and K modes (P = 0.000), with the BU II-TK and BU II-K formulas achieving the lowest medaes, respectively. In the 22.5 ≤ al ≤ 26 mm subgroup (n = 122), medaes.also differed significantly (P = 0.000) in both TK and K modes, with holladay 2-TK and BU II-K formulas presenting the lowest medaes. Notably, for BU II, the medae in K mode was significantly lower than in TK mode (P = 0.044). Within the al < 22.5 mm subgroup (n = 44), significant medae differences were found among formulas in TK mode (P = 0.028) and in K mode (P = 0.001), with the Haigis formula recording the lowest medae in both. For other statistically significant differences among formulas, pairwise comparison results are detailed in Tables 4 and the corresponding footnotes below.

Table 5 shows the maes, SDs and medaes calculated using the six formulas for the three ACD subgroups. In the acd > 3.50 mm subgroup (n = 30), medaes differed significantly across formulas in TK and K modes (P = 0.000), with the lowest medaes found for BU II in both modes. The 2.75 ≤ acd ≤ 3.50 mm subgroup (n = 130) also displayed significant medae differences (P = 0.000) across formulas in both modes, with BU II registering the lowest medaes. Conversely, in the acd < 2.75 mm subgroup (n = 52), there were no significant medae differences among the formulas in either mode (TK P = 0.630, K P = 0.381).

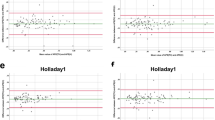

Table 6 shows the maes, SDs and medaes calculated using the six formulas for the three LT subgroups. In the lt > 4.8 mm subgroup (n = 46), no significant medae differences were found among formulas in either TK or K mode (TK P = 0.794, K P = 0.700). For the 4.2 ≤ lt ≤ 4.8 mm subgroup (n = 115), significant medae differences were observed across formulas in both TK and K modes (P = 0.000), with the BU II formula achieving the lowest medaes. Particularly in K mode, the BU II-K formula demonstrated the lowest medae, significantly differing from all other formulas: hoffer Q-K (P = 0.000), holladay 1-K (P = 0.000), holladay 2-K (P = 0.009), SRK/T-K (P = 0.009), and Haigis-K (P = 0.012). Additionally, BU II (P = 0.007) and hoffer Q (P = 0.033) formulas had lower medaes in K mode compared to TK mode. In the lt < 4.2 mm subgroup (n = 51), significant medae differences were noted across formulas in both TK and K modes (P = 0.000). In TK mode, the BU II-TK formula achieved the lowest medae, showing significant differences compared to all other formulas: hoffer Q-TK (P = 0.006), holladay 1-TK (P = 0.000), holladay 2-TK (P = 0.011), SRK/T-TK (P = 0.027), and Haigis-TK (P = 0.046). In K mode, the BU II-K formula exhibited the lowest medae, significantly differing from all other formulas except Haigis-K (P = 0.013), including hoffer Q-K (P = 0.003), holladay 1-K (P = 0.000), holladay 2-K (P = 0.002), and SRK/T-K (P = 0.003).

Table 7 shows the maes, SDs and medaes calculated using the six formulas for the three WTW subgroups. In the wtw > 12 mm subgroup (n = 50), significant differences in medae were noted across formulas in both TK (P = 0.037) and K (P = 0.003) modes, with BU II showing the lowest medaes. holladay 1 in TK mode had a lower medae compared to holladay 1 in K mode (P = 0.034), and holladay 2 in K mode had a lower medae compared to holladay 2 in TK mode (P = 0.012). Within the 11 ≤ wtw ≤ 12 mm subgroup (n = 138), significant medae differences were observed (P = 0.000) across formulas in both TK and K modes, with BU II again achieving the lowest medaes. For the wtw < 11 mm subgroup (n = 24), there were no significant differences in medae among formulas in either TK (P = 0.477) or K (P = 0.106) modes

Subgroup analysis with different average K value and ΔK values

Table 8 presents the MAEs, SDs and MedAEs for the three average K value subgroups using six formulas. For the subgroup with average K value > 46 D (n = 31), MedAE differences among formulas were not significant (P = 0.383), nor were they for the average K value < 42 D subgroup (n = 24) (P = 0.056). However, in the 42 ≤ average K value ≤ 46 D subgroup (n = 157), significant MedAE variations were found (P = 0.000), with the BU II formula yielding the lowest MedAE.

Table 8 also details the MAEs and MedAEs for the three ΔK value subgroups. In the ΔK value > 1.0 D subgroup (n = 49), BU II formula had the lowest medae, with significant differences noted across formulas (P = 0.001). For the 0.5 ≤ ΔK value ≤ 1.0 D subgroup (n = 91), holladay 2 formula demonstrated the lowest medae, with significant differences observed (P = 0.003). In the ΔK value < 0.5 D subgroup (n = 72), BU II formula again showed the lowest medae, with significant differences across formulas (P = 0.002).

Subgroup analysis with different average TK value and ΔTK value

Table 9 presents the MAEs, SDs and MedAEs for the three average TK value subgroups using six formulas. For the subgroup with average TK value > 46 D (n = 32), MedAE differences among formulas were not significant (P = 0.444), nor were they for the average TK value < 42 D subgroup (n = 22) (P = 0.097). However, in the 42 ≤ average TK value ≤ 46 D subgroup (n = 158), significant MedAE variations were found (P = 0.000), with the BU II formula yielding the lowest MedAE.

Table 9 also details the MAEs and MedAEs for the three ΔTK value subgroups. In the ΔTK value > 1.0 D subgroup (n = 59), Haigis formula had the lowest MedAE, with significant differences noted across formulas (P = 0.020). For the 0.5 ≤ ΔTK value ≤ 1.0 D subgroup (n = 87), BU II formula demonstrated the lowest MedAE, with significant differences observed (P = 0.027). In the ΔTK value < 0.5 D subgroup (n = 66), BU II formula again showed the lowest MedAE, with significant differences across formulas (P = 0.003).

Factors influencing refractive errors of the formulas

Multicollinearity analysis revealed significant collinearity between average K and average TK; therefore, only average TK was retained in the final regression model. The refractive errors predicted by BU II formula, whether using TK or K mode, showed no significant correlation with any preoperative biometric factors. The SRK/T-TK mode was correlated with ACD (β = 0.341, p = 0.001), LT (β = 0.303, p = 0.000), and average TK value (β=-0.299, p = 0.000). The SRK/T-K mode was correlated with ACD (β = 0.357, p = 0.000), LT (β = 0.314, p = 0.000), and average TK value (β=-0.367, p = 0.000). The Haigis-TK mode was correlated with AL (β = 0.328, p = 0.000), ACD (β = 0.275, p = 0.007), LT (β = 0.284, p = 0.001), and average TK value (β = 0.382, p = 0.000). The Haigis-K mode was correlated with AL (β = 0.241, p = 0.008), ACD (β = 0.321, p = 0.002), LT (β = 0.316, p = 0.000), and average TK value (β = 0.278, p = 0.001). The Hoffer Q-TK mode was correlated with AL (β = 0.456, p = 0.000), ACD (β = 0.370, p = 0.000), LT (β = 0.245, p = 0.001), and average TK value (β = 0.261, p = 0.001). The Hoffer Q-K mode was correlated with AL (β = 0.400, p = 0.000), ACD (β = 0.401, p = 0.000), LT (β = 0.268, p = 0.001), and average TK value (β = 0.181, p = 0.020). The Holladay 1-TK mode was correlated with AL (β = 0.380, p = 0.000), ACD (β = 0.314, p = 0.001), and LT (β = 0.279, p = 0.000). The Holladay 1-K mode was correlated with AL (β = 0.323, p = 0.000), ACD (β = 0.334, p = 0.001), and LT (β = 0.294, p = 0.000). The Holladay 2-TK mode was correlated with AL (β = 0.452, p = 0.000), WTW (β = 0.195, p = 0.014), and LT (β = 0.249, p = 0.002). The Holladay 2-K mode was correlated with AL (β = 0.394, p = 0.000), and LT (β = 0.271, p = 0.001).

Discussion

IOL power calculation accuracy depends on precise biometric measurements such as AL, K, ACD, LT, and WTW, as well as the formula used. The IOLMaster 700 measures these parameters and calculates IOL power using embedded formulas. It also features TK, accounting for both the anterior and posterior corneal curvatures and corneal thickness, allowing for complete corneal assessments6.

This study’s outcomes are consistent with those reported by Melles et al.,11 showing similar refractive accuracy and proportions of eyes within the ± 0.25 D to ± 1.00 D PE range for each formula. The BU II formula maintains its established high accuracy, consistent with numerous previous studies3,4,11,12. Our findings also confirm that the BU II formula has greater predictive accuracy than other formulas, evidenced by the lowest MedAEs and optimal PE distribution for both ± 0.50 D and ± 0.75 D.

Although TK incorporates both anterior and posterior corneal surfaces to provide a more comprehensive assessment of corneal power, its refractive advantage over K remains uncertain. While some studies have reported improved accuracy with TK when using formulas such as BU II and Haigis6, our results demonstrated that the BU II formula achieved greater predictive accuracy with K mode. Multiple investigations have shown that K provides more consistent refractive outcomes than TK when applied with formulas embedded in the IOLMaster 70018,19,20,21. We speculate that the reduced performance of TK mode may be attributed to incomplete optimization of formula constants for TK-derived values and to variability in posterior corneal measurements obtained via swept-source OCT. Additionally, TK-based prediction accuracy appears to be influenced by IOL design. Certain IOL models have been associated with significantly larger PEs when TK mode is used, particularly with BU II, Haigis, and Holladay 2 formulas19. The substitution of TK for K in the IOLMaster 700 has been reported to decrease the accuracy of several formulas20. In the context of multifocal IOL implantation, K mode has consistently demonstrated superior refractive performance compared to TK21.

In eyes categorized by AL, literature suggests that formulas like BU II, Haigis, and SRK/T offer improved accuracy for longer eyes22. Our findings confirm that for eyes with longer AL, the BU II formula achieves higher predictive accuracy over other formulas, regardless of using TK or K mode, and is evident through the lowest MAEs and MedAEs. The Haigis formula ranks second in performance following BU II. Conversely, Holladay 2 shows less predictive accuracy compared to others. Cooke et al. found that Haigis and BU II formulas provided superior accuracy in longer ALs4. Similarly, Carmona-Gonzalez et al. noted the BU II formula’s high precision in IOL power calculations for normal to long eyes23. Our study aligns with these findings, indicating that for medium ALs, the BU II formula achieved greater accuracy using K mode compared to others, while Holladay 2 was more precise with TK mode, both showing the lowest MAEs and MedAEs. Additionally, K mode yielded better results than TK mode within the BU II formula. These observations are consistent with those by Rocha-de-Lossada et al., who reported similar accuracy of BU II for medium ALs1. Kane et al. highlighted that BU II surpassed Haigis and Holladay 2 in precision for medium to long eyes, except in short eyes12. Notably, Haigis is recognized for its predictive accuracy in short eyes23. Our results indicate that BU II and Haigis are more precise than Hoffer Q and Holladay 2 for short ALs, specifically when utilizing K mode. These findings partly differ from previous reports which placed Haigis and Holladay 2 above BU II for short ALs22. Our analysis also revealed that among simple thin-lens vergence-based IOL formulas, none showed consistent superiority, apart from SRK/T, which exhibited greater accuracy than Holladay 1 in long ALs, irrespective of using TK or K mode, aligning with Aristodemou et al.'s research24. We speculate that the favorable performance of BU II in eyes with extreme AL, particularly in long eyes, may be attributed to its theoretical framework as an interactive thick-lens formula that integrates multiple biometric parameters in ELP prediction25. Haigis performed better in short eyes, possibly due to its greater emphasis on ACD and reduced dependence on AL, which may enhance its robustness when ELP prediction is more complex. Holladay 2 showed the best performance in eyes with medium AL, likely attributable to its multivariable regression model incorporating anatomical parameters such as LT, WTW, and ACD, which may allow for more individualized ELP estimation. Although Hoffer Q was originally developed for short eyes, its reliance on AL and K without incorporating additional anterior segment parameters may limit its adaptability across varying anatomical profiles. Similarly, SRK/T lacks direct consideration of ACD or LT, which may affect its performance in eyes with non-average biometry.

The role of ACD in ELP prediction has gained increasing attention with the progression of vergence-based IOL formulas. Earlier formulas such as Hoffer Q and SRK/T estimate ELP using non-linear equations based on AL, K, and personalized constants, without directly incorporating ACD. Holladay 1 applies a surgeon factor as a proxy rather than using actual ACD measurements26. Haigis improved upon this by including both ACD and AL in a linear regression model. More recently, BU II integrates ACD as one of several biometric inputs within a theoretical vergence-based framework to enhance ELP prediction27. Vega et al. emphasized the significance of ACD in BU II calculations28, whereas Savini et al. reported only a minimal effect29. In our study, BU II demonstrated superior accuracy in both deep and medium ACD subgroups, regardless of whether TK or K values were used, while Holladay 1 showed relatively lower performance. No single formula consistently outperformed others in shallow ACD eyes. We speculate that these differences may be attributed to how each formula models ELP in relation to ACD. BU II and Haigis, both of which directly incorporate ACD, may provide more individualized ELP estimates and improved accuracy in eyes with greater anterior segment variability. In contrast, formulas such as SRK/T and Hoffer Q, which do not explicitly include ACD, may be less adaptable in anatomically diverse eyes. The absence of significant differences in eyes with shallow ACD may warrant further investigation with larger sample sizes in future studies.

WTW distance, representing the horizontal corneal diameter, is incorporated into IOL power calculation formulas such as BU II and Holladay 2. While Vega et al. reported that omitting WTW from the BU II formula leads to only minimal changes28, our study found that BU II consistently achieved the lowest MAEs and MedAEs in both large and medium WTW subgroups, regardless of whether TK or K mode was used, outperforming Holladay 1, Hoffer Q, and Holladay 2. However, no formula demonstrated consistent superiority in eyes with small WTW. In Chinese cataract patients, larger WTW distances have been associated with flatter corneas, deeper ACDs, thicker lenses, and thinner central corneas30. Despite WTW being a parameter in Holladay 2, it did not confer an advantage in predictive accuracy across WTW subgroups in our data. We speculate that these findings may result from differences in how each formula incorporates WTW into ELP estimation. BU II, which integrates WTW within its theoretical model, may allow more individualized predictions in eyes with larger corneal diameters. Holladay 2 also includes WTW in its multivariable regression framework, though its performance varied between TK and K modes. In contrast, SRK/T, Hoffer Q, and Holladay 1 do not account for WTW, relying primarily on AL and K, which may limit their adaptability in eyes with atypical corneal sizes. The absence of significant differences in the WTW < 11 mm group may suggest limited variability in postoperative IOL positioning or reduced formula sensitivity in small corneal anatomies. Further investigation with larger cohorts may be warranted to confirm these trends.

LT is a recognized parameter in modern IOL power calculation formulas such as BU II and Holladay 2. However, previous studies have shown that incorporating LT does not consistently improve the accuracy of these formulas31,32. In our study, BU II demonstrated the highest precision in eyes with thin LT when using TK measurements and in medium LT eyes with K measurements, outperforming all other formulas. Although Holladay 2 includes LT within a multivariable regression model, it did not show superior accuracy in any LT subgroup compared to traditional formulas. A strong inverse relationship between ACD and LT has been documented33, which aligns with our findings. BU II provided superior accuracy in both deep and medium ACD groups as well as in thin and medium LT subgroups. This may reflect the flexibility of BU II’s theoretical ELP prediction model, which integrates LT along with other biometric parameters to accommodate variations in anterior segment anatomy. Haigis, though it does not include LT directly, may benefit from its ACD-based modeling, contributing to its favorable performance in thin LT eyes. In contrast, formulas such as SRK/T and Hoffer Q do not account for LT, relying solely on AL and K for ELP prediction. This may limit their performance in eyes with atypical LT.

Prior studies have indicated that corneas with flatter or steeper curvature are associated with higher prediction errors than those with regular power profiles34. BU II has demonstrated improved refractive outcomes and reduced sensitivity to corneal shape variations when compared with SRK/T, particularly in eyes with flat or steep corneas11,35. Qin et al. further supported the utility of BU II in such eyes, showing better outcomes in TK mode for flat and steep K subgroups10. These findings demonstrate that in eyes with varying corneal curvature, differences in ELP estimation algorithms among formulas can affect the accuracy of refractive prediction. Our results corroborate these findings, though the lack of significance in extreme groups may reflect underrepresentation. In eyes stratified by average corneal power using either K or TK values, the BU II formula consistently achieved the lowest MAEs and MedAEs across flat, normal, and steep subgroups. However, statistically significant differences among formulas were primarily observed in the 42–46 D range, where BU II outperformed all others. When subgrouped by ΔK or ΔTK, reflecting the magnitude of corneal astigmatism, formula-dependent performance was observed. BU II yielded the lowest MedAEs in both low (< 0.5 D) and moderate (0.5–1.0 D) astigmatism groups, regardless of using K or TK values, with statistically significant advantages over other formulas. In high astigmatism eyes (> 1.0 D), the Haigis formula showed superior performance, particularly in ΔTK-based analysis. We speculate that these findings may be attributed to differences in how each formula models and compensates for variations in corneal asphericity and symmetry. BU II incorporates both anterior and posterior corneal data through TK and integrates multiple biometric inputs within a theoretical vergence-based framework, potentially enhancing ELP prediction across a wide range of astigmatic profiles. Haigis, though not explicitly incorporating corneal asymmetry, uses ACD in its linear model and may offer greater adaptability in eyes with high astigmatism due to its weighting of anterior segment depth. In contrast, traditional formulas such as SRK/T, Hoffer Q, and Holladay 1 rely heavily on AL and average K, lacking mechanisms to address corneal asymmetry, which may limit their precision in highly astigmatic eyes. Although Holladay 2 integrates additional anatomical parameters, its performance was not consistently superior in ΔK- or ΔTK-stratified analyses.

Kim et al. reported that the accuracy of the SRK/T, Hoffer Q, Haigis, and Holladay 2 formulas was influenced by factors such as AL, ACD, K, and LT, with the exception of the BU II formula3. Rong et al. found that in myopic eyes, the accuracy of the Haigis formula was correlated with AL and K, while the accuracy of the BU II formula was only affected by AL36. Our findings indicate that refractive errors predicted by all formulas, except for the BU II, were significantly associated with LT. This could be due to the BU II formula already considering LT as a calculation parameter. AL, ACD, WTW distance, and average TK values showed a significant correlation with refractive errors in some formulas. However, the accuracy of all formulas was unaffected by the changes in ΔK and ΔTK. Notably, BU II was the only formula that showed no significant correlation between PEs and any biometric parameter (all p > 0.05), highlighting its robust performance. Although parameters such as age or ΔK are not utilized by all formulas, we included them in the multivariate regression analysis to explore their independent association with PE. This approach was not intended to replicate formula-specific mechanisms, but rather to identify anatomical or demographic factors that may influence refractive outcomes across the dataset. Our findings suggest that even parameters not directly used by the formulas can contribute to PE variability and warrant further consideration in future algorithm development.

Although this study focused on formulas embedded in the IOLMaster 700, these findings may help guide future development of AI-based IOL power calculation models. The observed variability in PE across K modes and biometric subgroups highlights the importance of multivariable modeling, which AI approaches may optimize by learning complex non-linear interactions beyond the scope of traditional formulas.

This study has several limitations. First, only a single IOL model was evaluated, which may limit the applicability of our findings to other lens types. Second, the sample distribution within subgroups was uneven, with larger numbers of cases in the “normal” biometric ranges and relatively fewer in extreme categories, potentially limiting the statistical power for subgroup comparisons. Third, the follow-up duration was relatively short, which may not fully reflect long-term refractive stability. Finally, all biometric measurements and IOL power calculations were based on the IOLMaster 700; thus, caution should be exercised when extrapolating these results to other biometry platforms beyond the IOLMaster 700.

In conclusion, the BU II formula demonstrated superior accuracy compared to other formulas in the overall sample as well as in the majority of conventional biometric subgroups. Particularly in cases with thin and medium LT, the BU II formula showed significant advantages. Conversely, the use of TK mode and K mode displayed no clear superiority in all subgroups, and in certain instances, K mode even outperformed TK mode. The accuracy of the BU II formula consistently remained unaffected by ocular parameters, further distinguishing it from other formulas.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Rocha-de-Lossada, C. et al. Intraocular lens power calculation formula accuracy: Comparison of 12 formulas for a trifocal hydrophilic intraocular lens. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 31, 2981–2988. https://doi.org/10.1177/1120672120980690 (2021).

Xu, J., Chen, X., Wang, H. & Yao, K. Safety of femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery versus conventional phacoemulsification for cataract: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Adv. Ophthalmol. Pract. Res. 2, 100027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aopr.2022.100027 (2022).

Kim, S. Y., Lee, S. H., Kim, N. R., Chin, H. S. & Jung, J. W. Accuracy of intraocular lens power calculation formulas using a swept-source optical biometer. PloS One. 15, e0227638. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227638 (2020).

Cooke, D. L. & Cooke, T. L. Comparison of 9 intraocular lens power calculation formulas. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 42, 1157–1164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2016.06.029 (2016).

LaHood, B. R. & Goggin, M. Measurement of posterior corneal astigmatism by the iolmaster 700. J. Refract. Surg. 34, 331–336. https://doi.org/10.3928/1081597X-20180214-02 (2018).

Fabian, E. & Wehner, W. Prediction accuracy of total keratometry compared to standard keratometry using different intraocular Lens power formulas. J. Refract. Surg. 35, 362–368. https://doi.org/10.3928/1081597X-20190422-02 (2019).

Akman, A., Asena, L. & Gungor, S. G. Evaluation and comparison of the new swept source OCT-based iolmaster 700 with the iolmaster 500. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 100, 1201–1205. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307779 (2016).

Srivannaboon, S. & Chirapapaisan, C. Comparison of refractive outcomes using conventional keratometry or total keratometry for IOL power calculation in cataract surgery. Graefe’s Archive Clin. Experimental Ophthalmol. = Albrecht Von Graefes Archiv fur Klinische Und Experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 257, 2677–2682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-019-04443-7 (2019).

Wang, L., Spektor, T., de Souza, R. G. & Koch, D. D. Evaluation of total keratometry and its accuracy for intraocular lens power calculation in eyes after corneal refractive surgery. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 45, 1416–1421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2019.05.020 (2019).

Qin, Y. et al. Accuracy of intraocular lens power calculation based on total keratometry in patients with flat and steep Corneas. Am. J. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2022.11.011 (2022).

Melles, R. B., Holladay, J. T. & Chang, W. J. Accuracy of intraocular lens calculation formulas. Ophthalmology 125, 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.08.027 (2018).

Kane, J. X., Van Heerden, A., Atik, A. & Petsoglou, C. Intraocular lens power formula accuracy: Comparison of 7 formulas. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 42, 1490–1500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2016.07.021 (2016).

Savini, G., Hoffer, K. J., Balducci, N., Barboni, P. & Schiano-Lomoriello, D. Comparison of formula accuracy for intraocular lens power calculation based on measurements by a swept-source optical coherence tomography optical biometer. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 46, 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2019.08.044 (2020).

Hoffer, K. J. et al. Protocols for studies of intraocular lens formula accuracy. Am. J. Ophthalmolo. 160, 403–405 e401 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2015.05.029

Zhang, Y. et al. Accuracy of intraocular Lens power calculation formulas for highly myopic eyes. J. Ophthalmol. 1917268. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/1917268 (2016).

Wang, L., Koch, D. D., Hill, W. & Abulafia, A. Pursuing perfection in intraocular lens calculations: III. Criteria for analyzing outcomes. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 43, 999–1002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2017.08.003 (2017).

Hoffer, K. J. & Savini, G. Update on intraocular Lens power calculation study protocols: The better way to design and report clinical trials. Ophthalmology 128, e115–e120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.07.005 (2021).

Ryu, S., Jun, I., Kim, T. I., Seo, K. Y. & Kim, E. K. Prediction accuracy of conventional and total keratometry for intraocular lens power calculation in femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery. Sci. Rep. 11, 12869. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92354-1 (2021).

Lee, H., Chung, J. L., Kim, Y. J., Kim, J. Y. & Tchah, H. Prediction accuracy of standard and total keratometry by swept-source optical biometer for multifocal intraocular lens power calculation. Sci. Rep. 11, 4794. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84238-1 (2021).

Danjo, Y., Ohji, R. & Maeno, S. Lower refractive prediction accuracy of total keratometry using intraocular lens formulas loaded onto a swept-source optical biometer. Graefe’s Archive Clin. Experimental Ophthalmol. = Albrecht Von Graefes Archiv fur Klinische Und Experimentelle Ophthalmologie. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-022-05777-5 (2022).

Chung, H. S. et al. Comparing prediction accuracy between total keratometry and conventional keratometry in cataract surgery with refractive multifocal intraocular lens implantation. Sci. Rep. 11, 19234. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-98491-x (2021).

Hoffer, K. J. & Savini, G. I. O. L. Power calculation in short and long eyes. Asia Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 6, 330–331. https://doi.org/10.22608/APO.2017338 (2017).

Carmona-Gonzalez, D., Castillo-Gomez, A., Palomino-Bautista, C., Romero-Dominguez, M. & Gutierrez-Moreno, M. A. Comparison of the accuracy of 11 intraocular lens power calculation formulas. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 31, 2370–2376. https://doi.org/10.1177/1120672120962030 (2021).

Aristodemou, P., Knox Cartwright, N. E., Sparrow, J. M. & Johnston, R. L. Formula choice: Hoffer Q, holladay 1, or SRK/T and refractive outcomes in 8108 eyes after cataract surgery with biometry by partial coherence interferometry. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 37, 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2010.07.032 (2011).

Stopyra, W., Langenbucher, A. & Grzybowski, A. Intraocular lens power calculation formulas—a systematic review. Ophthalmol. Ther. 12, 2881–2902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-023-00799-6 (2023).

Langenbucher, A., Haigis, W. & Seitz, B. Difficult lens power calculations. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 15, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00055735-200402000-00002 (2004).

Muniz Castro, H. et al. Accuracy of intraocular Lens power calculation using anterior chamber depth from two devices with Barrett universal II formula. J. Ophthalmol. 2019 (8172615). https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/8172615 (2019).

Vega, Y. et al. High agreement between Barrett universal II calculations with and without utilization of optional biometry parameters. J. Clin. Med. 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10030542 (2021).

Savini, G. et al. Comparison of 13 formulas for IOL power calculation with measurements from partial coherence interferometry. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 105, 484–489. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-316193 (2021).

Wei, L. et al. Evaluation of the White-to-White distance in 39,986 Chinese cataractous eyes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 62, 7. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.62.1.7 (2021).

Taroni, L., Hoffer, K. J., Lupardi, E., Barboni, P. & Savini, G. Accuracy of new intraocular Lens power calculation formulas: A Lens thickness study. J. Refract. Surg. 37, 202–206. https://doi.org/10.3928/1081597X-20210104-01 (2021).

Srivannaboon, S., Chirapapaisan, C., Chirapapaisan, N., Lertsuwanroj, B. & Chongchareon, M. Accuracy of holladay 2 formula using iolmaster parameters in the absence of lens thickness value. Graefe’s Archive Clin. Experimental Ophthalmol. = Albrecht Von Graefes Archiv fur Klinische Und Experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 251, 2563–2567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-013-2439-8 (2013).

Feng, X. et al. Analysis of lens thickness distribution based on swept-source optical coherence tomography (SS-OCT). J Ophthalmol 4717996 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/4717996

Kim, J. W. et al. Algorithmic intraocular lens power calculation formula selection by keratometry, anterior chamber depth and axial length. Acta Ophthalmol. 100, e701–e709. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.14956 (2022).

Iijima, K., Kamiya, K., Iida, Y. & Shoji, N. Comparison of predictability using Barrett universal II and SRK/T formulas according to keratometry. J. Ophthalmol. 2020 (7625725). https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7625725 (2020).

Rong, X. et al. Intraocular lens power calculation in eyes with extreme myopia: comparison of Barrett Universal II, Haigis, and Olsen formulas. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 45, 732–737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2018.12.025 (2019).

Funding

This study was supported by research grants from the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (LMS25H120001), the National Nature Science Foundation of China (82271042) and the Zhejiang Province Key Research and Development Program (2023C03090).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design SN, JW; data collection DL, ZX; statistical expertise JWX YF; analysis and interpretation SZ, CS; writing the article SN, JW; critical revision of the article SN, WX; final approval of the article WX; All authors reviewed the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (ID 2023-0013). All procedures adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the need to obtain the informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ni, S., Wang, J., Lyu, D. et al. Accuracy comparison of six intraocular lens formulas using total and standard keratometry measurements with the iolmaster 700. Sci Rep 15, 26095 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11332-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11332-z