Abstract

The outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic is a breach of health protection worldwide. Complications in people who limit the risk of COVID-19 can be associated with physical and mental health. Identification of states associated with anxiety and depression and threats that may occur in patients after COVID-19 is a very important aspect that occurs on the selection of therapeutic methods, and thus recovery occurs. The aim of the study was to assess the penalty in the treatment of anxiety symptoms and depressiveness in a patient after COVID-19. The study includes the effects resulting from brain-derived neurotrophic factor, irisin and other problems related to problems and depressive symptoms in patients after COVID-19. included in the study participation in the rehabilitation education program in stationary conditions. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire was used to solve anxiety problems. The Beck Depression Inventory was used to assess the effects of depression. To assess the update of the irisin (ng/mL) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (ng/mL) configuration on the day of treatment initiation from each patient’s blood was collected from a female venous sample. After rehabilitation, patients scored lower in both depression and anxiety assessments. Women had higher scores in the assessment of anxiety disorders and depression. The longer the period from the end of COVID-19 treatment to the start of rehabilitation, the higher the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire and The Beck Depression Inventory scores. The higher the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire and The Beck Depression Inventory scores, the lower the handgrip strength values. With increasing irisin concentration, The Beck Depression Inventory values also increased. Comprehensive rehabilitation may be associated with a reduction in the severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients after COVID-19. Earlier initiation of rehabilitation may be associated with better emotional well-being in patients after COVID-19. The severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms may be associated with gender, age, and hospitalization during COVID-19 treatment. Increased irisin levels in patients after COVID-19 may be associated with inflammatory and metabolic complications after infection. However, interpretation of these relationships requires further studies taking into account additional biological variables and prospective analyses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

COVID-19 infection can lead to numerous complications, resulting in multifaceted disability. While significant clinical attention and research have focused on addressing the physiological consequences of the disease, the psychological effects of the virus in infected patients must also be considered1,2. Identifying anxiety- and depression-related conditions, along with risk factors for their occurrence in post-COVID-19 patients, is a crucial aspect in selecting appropriate therapeutic approaches, thereby facilitating a faster recovery3.

Studies have demonstrated that hospitalization in intensive care units and the use of mechanical ventilation are risk factors for the development of mental disorders and post-intensive care syndrome (PICS). Given this, it is possible that COVID-19 patients requiring intensive care may be at high risk of developing psychiatric disorders4,5,6. Moreover, mental health issues are exacerbated by social isolation and mandatory quarantine aimed at controlling viral spread. Previous population-based studies have shown that individuals affected by the COVID-19 pandemic exhibited increased alcohol consumption, eating disorders, sleep disturbances, and episodes of anxiety and depression7,8.

Despite recovery from COVID-19 and hospital discharge, persistent complications and health problems can significantly impact patients’ quality of life. This underscores the importance of rehabilitation for both physical and mental health9,10,11. Numerous studies indicate that regular physical activity can reduce the risk of various diseases, including depression and anxiety12,13.

Regular exercise promotes neurogenesis, angiogenesis, and synaptogenesis, positively affecting brain function. This is partly facilitated by neurotrophins. One of them is brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF has been associated with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, intellectual disability, autism, and mood disorders, including depression and anxiety. Studies have suggested that BDNF may serve as a potential biomarker for COVID-19 severity. For example, BDNF levels in patients with severe and moderate COVID-19 were lower than in those with mild cases. Lower BDNF concentrations have been linked to unfavorable COVID-19 outcomes14,15,16. Research indicates that decreased BDNF levels result from the SARS-CoV-2 virus inhibiting the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor, which may lead to neurodegeneration and psychiatric disorders such as anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment, thereby contributing to a more severe course of COVID-1915,17.

Recent studies suggest that irisin (IRIS) plays a role in improving brain damage and depressive behaviors. IRIS is an adipomyokine primarily released into the bloodstream by skeletal muscles. It has been demonstrated that IRIS crosses the blood-brain barrier and influences neuronal function in the prefrontal cortex18,19. Studies suggest that IRIS may contribute to mood improvement and alleviate depressive symptoms by promoting BDNF expression in the brain20. The suppression of depressive symptoms may also be explained by the effect of IRIS on the activation of the PGC-1α-FNDC5/irisin pathway in the hippocampus21,22. However, no direct evidence has been found regarding the role of IRIS in modulating emotional states in post-COVID-19 patients.

The aim of this study was to assess the significance of rehabilitation in reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms in post-COVID-19 patients. Additionally, the study aimed to investigate the relationships between BDNF levels, IRIS concentrations, and other clinical factors and the severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms in post-COVID-19 patients.

Materials and methods

Patient eligibility for the study

Recruitment of patients for the study was conducted from May 2021 to September 2022. Patients were recruited at the St. Charles Borromeo Rehabilitation Hospital in Szczecin, where inpatient therapeutic rehabilitation was provided after SARS-CoV-2 infection. The Post-COVID-19 Rehabilitation Ward accepted patients recovering from COVID-19, based on a referral issued by a general practitioner. The final qualification for post-COVID-19 rehabilitation was made by a medical rehabilitation physician from the Rehabilitation Hospital based on specific criteria specified in the guidelines of the National Health Fund (NFZ), in accordance with Order No. 42/2021/DSOZ of the President of the National Health Fund of March 5, 202123.

Inclusion in the rehabilitation program required the presence of post-COVID-19 complications, assessed based on:

-

The Post-COVID-19 Functional Status (PCFS) Scale (score 1–4).

-

The Medical Research Council (MRC) Scale (score < 5).

-

The Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) Scale (score ≥ 1).

The Post-COVID-19 Functional Status Scale is a five-point scale used to identify patients with functional limitations related to various aspects of health following COVID-1924. The Medical Research Council Scale is used to assess muscle strength on a scale from 0 to 5, where 0 indicates no muscle contraction and 5 represents normal muscle strength25. The Modified Medical Research Council Scale is a five-point scale evaluating the severity of dyspnea, where 0 represents breathlessness only during physical exertion, and 4 denotes breathlessness preventing the patient from leaving home26.

A total of 167 patients were included in the study based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The study was open to participants over 18 years of age who had previously been confirmed to be infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus based on a positive PCR test result. Eligibility also required that no more than 12 months had passed since the end of COVID-19 treatment and that participants had given informed consent to participate in the study, including consent to collect biological material (blood). Minors, people who did not consent to blood collection, and participants whose health condition prevented them from giving informed consent or understanding the purpose and conditions of participation in the project were excluded from the study. Additional exclusion factors included: neurodegenerative or neurodevelopmental disorders, musculoskeletal disorders that prevented participation in rehabilitation, and severe cardiovascular diseases, including heart failure in class III or IV according to the NYHA classification, having had an acute coronary syndrome in the last three months, and uncontrolled hypertension. People with epilepsy, malignant tumors, or who had undergone surgery less than 30 days before starting the study were also excluded from participation.

Each patient gave written informed consent to participate in this study and to use data from their medical records. Every effort has been made to protect the privacy and anonymity of patients. The study was conducted in accordance with the current version of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Bioethics Committee of the Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin (decision no. KB-0012/15/2021).

Study process

Patients included in the study participated in a comprehensive inpatient rehabilitation program. The type and scope of rehabilitation procedures are presented in Fig. 1. Exercises were conducted six times per week for a period ranging from 2 to 6 weeks. The length of stay in the Post-COVID-19 Rehabilitation Unit was determined by the attending physician. Throughout the rehabilitation period, the patient was under medical, nursing, and physiotherapeutic supervision.

To assess anxiety and depressive symptoms, participants completed diagnostic questionnaires before and after rehabilitation. Standardized tools adapted to Polish conditions were used.

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7) was applied to identify anxiety disorders. It is a screening tool used to assess symptoms related to generalized anxiety disorder. The questionnaire consists of seven items, rated on a scale from 0 to 3. The total score is interpreted as follows: 0–4 (no anxiety), 5–9 (mild anxiety), 10–14 (moderate anxiety), and 15–21 (severe anxiety)27,28. The GAD7 version was translated into Polish by the MAPI Research Institute. Considering the results, the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for the questionnaire in our study was α = 0.94. The criterion validity of GAD 7 was confirmed in comparison with a clinical interview (SCID) – for a cut-off point of ≥ 10, a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 82% in diagnosing anxiety disorders were obtained27,29,30.

To assess depressive symptoms, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) was used. This questionnaire consists of 21 items, each with four response options scored from 0 to 3. The final score is calculated by summing the points obtained from each question and interpreted as follows: 0–13 (no depression or minimal depressive symptoms), 14–19 (mild depression), 20–28 (moderate depression), and 29–63 (severe depression)31,32. Numerous population and clinical studies have confirmed its high reliability (α ≈ 0.90–0.95) and test–retest repeatability (r = 0.73–0.96). The BDI II questionnaire demonstrates strong convergent validity – including a high correlation with the PHQ 9 (r = 0.85) and the CES D (r = 0.86)33,34.

Before and after rehabilitation, participants underwent a handgrip strength assessment using a Charder MG 4800 handheld dynamometer (Charder Electronic Co., Taichung, Taiwan). During the measurement, participants remained seated with their arms adducted and elbows flexed at a 90° angle. Measurements were performed on the dominant hand, and the recorded values were displayed digitally with an accuracy of 0.1 kg. Three trials were conducted, and the highest grip strength (kg) was considered for analysis.

On the first day of rehabilitation, an interview was conducted with each participant to obtain sociodemographic data. Information regarding the course of illness, treatment history, and comorbidities was obtained from medical records.

To evaluate IRIS (ng/mL) and BDNF (ng/mL) levels, blood samples were collected from the cubital vein on the first day of rehabilitation. Blood was drawn by qualified nurses following standard procedures and protocols. The blood was collected in tubes containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Plasma obtained through centrifugation was frozen and stored at −80 °C until laboratory analyses were performed. All measurements were conducted using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits from Sun Red Biotechnology Company, Shanghai, China, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 13.1 software (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). Descriptive statistics, including the number of patients, percentages, mean, and standard deviation, were used to characterize the study group. Normality of distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Differences between te two groups were analyzed using the Student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney U test. Correlation analysis was conducted using Spearman’s Rho test. Statistical significance was assigned to results with a p-value < 0.05.

Results

A total of 167 patients participated in the study. The mean age of the study group was 64.65 years. Table 1 presents a detailed characterization of the study group.

Given the complexity of the analyses conducted and the clarity of the results presented in the article, only statistically significant results are included.

Table 2 presents a comparison of BDI-II and GAD-7 scores before and after rehabilitation. After rehabilitation, patients demonstrated significantly lower scores for both depression and anxiety (< 0.001*).

Table 3 presents intergroup comparisons for BDI-II and GAD-7 scores before and after rehabilitation. Before the rehabilitation began, significant differences in the intensity of depression symptoms (BDI-II) and anxiety (GAD-7) were observed between the sexes — women showed higher scores on both scales (p = 0.011 for BDI-II and p = 0.017 for GAD-7). After the rehabilitation, significant differences in the intensity of anxiety (GAD-7) remained in relation to gender (p = 0.007) and age (p = 0.048). Significant differences after rehabilitation were also noted between hospitalized and non-hospitalized individuals, both in terms of depression (p = 0.022) and anxiety (p < 0.001).

Table 4 presents correlations between the time elapsed from COVID-19 treatment completion to the start of rehabilitation, BDNF, IRIS, and upper limb strength with BDI-II and GAD-7 scores measured before rehabilitation. The analysis showed that the time from the end of COVID-19 treatment to the start of rehabilitation is significantly associated with the severity of depression and anxiety symptoms (p = 0.019 and p = 0.038, respectively). The IRIS variable showed a significant correlation with the severity of depression symptoms (p = 0.012). Statistically significant correlations were observed between grip strength and the severity of depression and anxiety (p < 0.001 in both cases).

Discussion

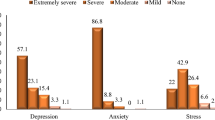

Depression and anxiety are significant public health concerns. Post-COVID-19 patients may be at an increased risk of developing mental health issues. Studies on anxiety and depression in COVID-19 patients indicate that the prevalence of anxiety disorders ranges from 6 to 63%, while depressive symptoms occur in 4–31% of cases35. Comparable prevalence rates have been observed even up to six months after the acute infection36,37. Our study confirmed that as many as 52.7% of participants exhibited at least mild depressive symptoms, and 61.1% experienced at least mild anxiety symptoms up to 12 months after the acute phase of the disease. The presence of negative consequences of infection, posing a significant threat to psychological well-being, particularly in the context of the long-term course of COVID-19, has led to the search for predictive factors associated with an increased risk of developing mental health disorders. Additionally, this study assessed the role of physical activity as a potential protective factor against anxiety and depressive symptoms.

According to the results of this study, comprehensive rehabilitation may be associated with a reduction in the severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients after COVID-19. Reports by other authors indicate that physical activity may play an important role in alleviating mental disorders in patients after COVID-1938,39,40. Physical exercise may affect anxiety and depressive symptoms through various biological mechanisms. Studies suggest that regular physical activity may reduce oxidative stress and chronic inflammation, while improving mitochondrial function41,42. In addition, it has been shown that physical exercise can modulate the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which is crucial for mood regulation43. Another theory relates to disorders of the gut microbiota and the beneficial effect of physical activity on its composition44,45. Based on the available literature data, it can be assumed that exercise therapy is a potentially effective complement to mental support in patients after COVID-19. There is also evidence indicating that regular physical activity may bring comparable effects to psychotherapy or pharmacological treatment in terms of relieving symptoms of mental disorders46,47. However, further prospective and experimental studies are necessary to confirm the effectiveness of such an intervention in the context of post-traumatic stress associated with COVID-19.

Our study demonstrated a positive correlation between the severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms and the time elapsed from COVID-19 treatment completion to the start of rehabilitation. This indicates that individuals who began rehabilitation later, up to 12 months after treatment completion, exhibited higher levels of depressive and anxiety-related behaviors, as measured by the BDI-II and GAD-7 scales. This finding highlights the importance of initiating rehabilitation as early as possible in the recovery process.

The findings regarding sociodemographic predictors of depression and generalized anxiety are particularly noteworthy. In our study, significant differences in the severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms were observed depending on sex. Women exhibited higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms before rehabilitation, as well as higher anxiety levels after rehabilitation. Numerous studies confirm that women are more susceptible to developing mental health disorders48,49,50. Several theories attempt to explain these sex-based differences. One hypothesis attributes them to biological differences in brain structures and fluctuations in sex hormones. Additionally, women tend to show greater vulnerability to stressful life events51.

Our study also revealed that individuals over 65 years of age experienced greater anxiety symptom severity after rehabilitation compared to those under 65 years old. Similar observations were highlighted by Smolarczyk-Kosowska et al.40, who found that the severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic had a negative correlation with age. However, some contradictory findings suggest that older age is associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety52. These discrepancies warrant further research into predictors of depression and anxiety, as well as the underlying causes of these differences.

The results of this study suggest that people who were not hospitalized due to COVID-19 showed higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms compared to those who were hospitalized. Although this may seem inconsistent with previous reports suggesting that prolonged hospitalization, including intensive care unit stay, increases the risk of developing mental disorders4,5,6, the obtained results may indicate a different mechanism. It can be speculated that people who were not hospitalized may have experienced greater uncertainty about their health status, lack of formal medical care, or social isolation. However, it should be noted that these factors were not directly measured in this study, so their influence on the obtained results cannot be unequivocally confirmed. Therefore, the presented interpretation remains a hypothesis that should be verified in future studies using appropriate tools to assess the level of isolation, social support, and health risk perception.

In our study, a negative correlation was observed between handgrip strength and the results obtained in the GAD-7 and BDI-II questionnaires. This means that lower grip strength values were statistically associated with higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms. These results are consistent with previous reports on the co-occurrence of reduced muscle strength with symptoms of mood disorders53,54. However, it should be emphasized that the observed relationships are correlational and do not allow for conclusions about causal relationships. Although physical activity is a known factor contributing to the improvement of muscle strength and performance, and may also play a role in reducing depressive and anxiety symptoms, these relationships require further research in prospective and interventional models. Nevertheless, these results may support the hypothesis about the potential role of physical activity as a factor supporting mental and physical health after COVID-19.

In this study, we analyzed the relationship between BDNF and IRIS levels and the severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients after COVID-19. In light of previous scientific reports, higher IRIS levels were usually associated with better mood and lower depression severity55,56. The obtained results showed a positive correlation between IRIS levels and the severity of depressive symptoms, which seems to be inconsistent with expectations. In interpreting this result, we referred to the hypothesis that in people after COVID-19, increased IRIS levels may reflect the body’s compensatory response to disturbed homeostasis, including chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, muscle tissue regeneration or other post-infectious complications. IRIS has anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects, and its increase may be a defensive reaction aimed at counteracting the negative consequences of COVID-1957,58,59. Moreover, as indicated by previous studies, depression in post-COVID-19 patients may be related to persistent inflammation, which itself may lead to increased production of IRIS. Buscemi et al.60 showed that patients with high levels of systemic inflammation had significantly higher levels of IRIS compared to the general population. However, it should be clearly emphasized that such an explanation is speculative. This analysis did not include direct measurements of inflammatory markers or metabolic parameters, which limits the possibility of inferring the biological mechanisms underlying the observed relationships. Further studies using a comprehensive assessment of inflammation, metabolism, and physical activity are necessary to clearly determine the significance of IRIS in the context of mood disorders after COVID-19. A better understanding of these mechanisms could help optimize support strategies for post-COVID-19 patients, potentially through targeted anti-inflammatory or metabolic interventions for individuals who, despite high IRIS levels, continue to experience depressive symptoms.

Limitations and strengths

The strengths of this study include a well-defined population of post-COVID-19 patients with comprehensive information, including hospital and personal data. However, this study also has certain limitations. The lack of data on the mental health and physical activity level of the participants before falling ill makes it impossible to establish a causal relationship between the past infection and the observed symptoms. Additionally, the varying time from the completion of COVID-19 treatment to rehabilitation – though not exceeding 12 months – may have influenced the reported results. One of the limitations of the study is the lack of information on the antidepressant and antianxiety pharmacotherapy used by the participants. The type of medication or the time of its administration was not analyzed, which could have influenced the results. It is recommended to control this factor as an important variable in future studies. Another limitation of the study is the lack of both a control group and a comparison group. This makes it difficult to clearly interpret whether the observed psychological and somatic symptoms are directly related to the SARS-CoV-2 infection. The mental state of the participants was assessed solely using standardized self-assessment questionnaires, without conducting a clinical interview by a psychiatrist. Although the instruments used are validated and commonly used in population studies, the lack of a diagnostic expert assessment is a methodological limitation. In this study, cognitive function was not assessed for participants aged 60 years and older, which should be considered a limitation. For participants aged 60 years and older, mental status may be partially determined by natural aging processes, including cognitive decline. Future studies are recommended to include screening tools for cognitive performance and control for age-related variables. Despite these limitations, this study provides important findings and may serve as a starting point for broader research on the role of comprehensive rehabilitation, BDNF levels, IRIS, and other clinical factors in relation to the mental health of post-COVID-19 patients.

Conclusions

Comprehensive rehabilitation may be associated with a reduction in the severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients after COVID-19. Earlier initiation of rehabilitation may be associated with better emotional well-being in patients after COVID-19. The severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms may be associated with gender, age, and hospitalization during COVID-19 treatment. Increased IRIS levels in patients after COVID-19 may be associated with inflammatory and metabolic complications after infection. However, interpretation of these relationships requires further studies taking into account additional biological variables and prospective analyses.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Khan, S. et al. Impact of coronavirus outbreak on psychological health. J. Glob Health. 10 (1), 010331. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.10.010331 (2020).

Kim, H. C., Yoo, S. Y., Lee, B. H., Lee, S. H. & Shin, H. S. Psychiatric findings in suspected and confirmed middle East respiratory syndrome patients quarantined in hospital: A retrospective chart analysis. Psychiatry Investig. 15 (4), 355–360 (2018).

Salari, N. et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health. 6 (1), 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w (2020).

Hassett, C. E. et al. Neurologic complications of COVID-19. Cleve Clin. J. Med. 87 (12), 729–734 (2020).

Dinakaran, D., Manjunatha, N., Kumar, N. & Suresh, C. Neuropsychiatric aspects of COVID-19 pandemic: A selective review. Asian J. Psychiatr. 53, 102188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102188 (2020).

Chen, N. et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in wuhan, china: a descriptive study. Lancet 15 (10223), 507–513 (2020).

Devi, S. Travel restrictions hampering COVID-19 response. Lancet 25 (10233), 1331–1332 (2020).

Omarini, C. et al. Cancer treatment during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: do not postpone, do it! Eur. J. Cancer. 133, 29–32 (2020).

Si, M. Y. et al. Mindfulness-based online intervention on mental health and quality of life among COVID-19 patients in china: an intervention design. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 17 (1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-021-00836-1 (2021).

Beom, J. et al. Early rehabilitation in a critically ill inpatient with COVID-19. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil Med. 56 (6), 858–861 (2020).

Sun, T. et al. Rehabilitation of patients with COVID19. Expert Rev. Respir Med. 14 (12), 1249–1256 (2020).

Wu, C. et al. Effects of exercise training on Anxious-Depressive-like behavior in alzheimer rat. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 52 (7), 1456–1469 (2020).

Yates, B. E., DeLetter, M. C. & Parrish, E. M. Prescribed exercise for the treatment of depression in a college population: an interprofessional approach. Perspect. Psychiatr Care. 56 (4), 894–899 (2020).

Cassilhas, R. C., Tufik, S. & De Mello, M. T. Physical exercise, neuroplasticity, Spatial learning and memory. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 975–983 (2016).

Azoulay, D. et al. Recovery from SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with serum BDNF. Restor. J. Infect. 81 (3), e79–e81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.038 (2020).

Minuzzi, L. G. et al. COVID-19 outcome relates with Circulating BDNF, according to patient adiposity and age. 8, 784429 ; (2021). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.784429

Lu, B., Nagappan, G. & Lu, Y. BDNF and synaptic plasticity, cognitive function, and dysfunction. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 220, 223–250 (2014).

Carvalho, A. F. et al. Adipokines as emerging depression biomarkers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr Res. 59, 28–37 (2014).

Wang, S. & Pan, J. Irisin ameliorates depressive-like behaviors in rats by regulating energy metabolism. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 474, 22–28 (2016).

Papp, C. et al. Alteration of the irisin-brain-derived neurotrophic factor axis contributes to disturbance of mood in COPD patients. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 12, 2023–2033 (2017).

Schuch, F. B. et al. Exercise as a treatment for depression: a meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. J. Psychiatr Res. 77, 42–51 (2016).

Wrann, C. D. FNDC5/irisin - their role in the nervous system and as a mediator for beneficial effects of exercise on the brain. Br. Plast. 1, 55–61 (2015).

Order of the President of the National Health Fund No. 172/2021/DSOZ of 18 October 2021. Available online: March (2023). https://baw.nfz.gov.pl/NFZ/tabBrowser/mainPage (accessed on 9.

Klok, F. A. et al. The Post-COVID-19 functional status scale: A tool to measure functional status over time after COVID-19. Eur. Respir J. 56, 2001494 (2020).

Paternostro-Sluga, T. et al. Reliability and validity of the medical research Council (MRC) scale and a modified scale for testing muscle strength in patients with radial palsy. J. Rehabil Med. 40, 665–671 (2008).

Hayata, A., Minakata, Y., Matsunaga, K., Nakanishi, M. & Yamamoto, N. Differences in physical activity according to mMRC grade in patients with COPD. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 11, 2203–2208 (2016).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. & Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 1092–1097 (2006).

Basińska, B. A. & Kwissa-Gajewska, Z. Psychometric properties of the Polish version of the generalized anxiety disorder 7-Item scale (Gad-7) in a Non-Clinical sample of employees during pandemic crisis. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health. 36, 493 (2023).

Löwe, B. et al. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med. Care. 46 (3), 266–274 (2008).

Hinz, A. et al. Psychometric evaluation of the generalized anxiety disorder screener GAD-7, based on a large German general population sample. J. Affect. Disord. 210, 338–344 (2017).

Titov, N., Dear, B. F. & McMillan, D. Psychometric comparison of the PHQ-9 and BDI-II for measuring response during treatment of depression. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 40, 126–136 (2011).

Zawadzki, B., Popiel, A. & Pragłowska, E. Charakterystyka psychometryczna Polskiej Adaptacji Kwestionariusza Depresji BDI-II Aarona. T Becka Psychol. Etiol Genet. 19, 71–94 (2009).

Wang, Y. P. & Gorenstein, C. Psychometric properties of the Beck depression Inventory-II: a comprehensive review. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 35 (4), 416–431 (2013).

Dozois, D. J. A., Dobson, K. S. & Ahnberg, J. L. A psychometric evaluation of the Beck depression Inventory–II. Psychol. Assess. 10 (2), 83–89 (1998).

Shanbehzadeh, S., Tavahomi, M., Zanjari, N., Ebrahimi-Takamjani, I. & Amiri-Arimi, S. Physical and mental health complications post-COVID-19: Scoping review. J. Psychosom. Res.147:110525;10.1016/j.jpsychores.11052 (2021). (2021).

Premraj, L. et al. Mid and long-term neurological and neuropsychiatric manifestations of post-COVID-19 syndrome: A meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Sci. 434, 120162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2022.120162 (2022).

Deng, J. et al. The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID-19 patients: A meta-analysis. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1486, 90–111 (2021).

Tang, J., Chen, L. L., Zhang, H., Wei, P. & Miao, F. Effects of exercise therapy on anxiety and depression in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public. Health. 6, 12:1330521. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1330521 (2024).

Kupferschmitt, A. et al. Attention deficits and depressive symptoms improve differentially after rehabilitation of post-COVID condition - A prospective cohort study. J. Psychosom. Res. 175, 111540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2023.111540 (2023).

Smolarczyk-Kosowska, J. Assessment of the impact of a daily rehabilitation program on anxiety and depression symptoms and the quality of life of people with mental disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 3 (4), 1434. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041434 (2021).

Angulo, J., El Assar, M., Álvarez-Bustos, A. & Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Physical activity and exercise: strategies to manage frailty. Redox Biol. 35, 101513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2020.101513 (2020).

Wang, X., Wang, Z. & Tang, D. Aerobic exercise alleviates inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in mice with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 16, 1369–1379 (2021).

Dionysopoulou, S. et al. The role of hypothalamic inflammation in diet-induced obesity and its association with cognitive and mood disorders. Nutrients 13, 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020498 (2021).

Simpson, C. A. et al. The gut microbiota in anxiety and depression—a systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 83, 101943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101943 (2021).

Xia, W. J. et al. Antihypertensive effects of exercise involve reshaping of gut microbiota and improvement of gut-brain axis in spontaneously hypertensive rat. Gut Microbes. 13, 1–24 (2021).

Singh, B. et al. Skuteczność interwencji w Zakresie Aktywności Fizycznej w Celu Poprawy depresji, Lęku i stresu: Przegląd Przeglądów systematycznych. Br. J. Sports Med. 57, 1203–1209 (2023).

Piva, T. et al. Exercise program for the management of anxiety and depression in adults and elderly subjects: is it applicable to patients with post-covid-19 condition? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 15, 325, 273–281 (2023).

Taha, P. et al. Depression and generalized anxiety as Long-Term mental health consequences of COVID-19 in Iraqi Kurdistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 7 (13), 6319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136319 (2023).

Wu, Y. et al. Nervous system involvement after infection with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Brain Behav. Immun. 87, 18–22 (2022).

Halpin, S. J. Postdischarge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of COVID-19 infection: A cross-sectional evaluation. J. Med. Virol. 93, 1013–1022 (2021).

Farhane-Medina, N. Z., Luque, B., Tabernero, C. & Castillo-Mayén, R. Factors associated with gender and sex differences in anxiety prevalence and comorbidity: A systematic review. Sci. Prog. 105, 00368504221135469. https://doi.org/10.1177/00368504221135469 (2022).

Maier, A., Riedel-Heller, S. G., Pabst, A. & Luppa, M. Risk factors and protective factors of depression in older people 65+. A systematic review. PLoS One. 13 (5), e0251326. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251326 (2021).

Zasadzka, E., Pieczyńska, A., Trzmiel, T., Kleka, P. & Pawlaczyk, M. Correlation between handgrip strength and depression in older Adults-A systematic review and a Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 30 (9), 4823. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094823 (2021).

Zhang, X. M. et al. Handgrip strength and depression among older Chinese inpatients: A Cross-Sectional study. Neuropsychiatr Dis. Treat. 30, 17, 1267–1277 (2021).

Jo, D. & Song, J. Irisin acts via the PGC-1α and BDNF pathway to improve Depression-like behavior. Clin. Nutr. Res. 20 (4), 292–302 (2021).

Zhang, Q. X., Zhang, L. J., Zhao, N. & Yang, L. Irisin in ischemic stroke, alzheimer’s disease and depression: a narrative review. Brain Res. 15, 1845 (2024).

Arhire, L. I., Mihalache, L., Covasa, M. & Irisin A hope in Understanding and managing obesity and metabolic syndrome. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 10, 524 (2019).

Eslampour, E. et al. Association between Circulating Irisin and C-Reactive protein levels: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Endocrinol. Metab. (Seoul). 34 (2), 140–149 (2019).

Slate-Romano, J. J., Yano, N. & Zhao, T. C. Irisin reduces inflammatory signaling pathways in inflammation-mediated metabolic syndrome. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 552, 111676 (2022).

Buscemi, S. et al. Serum Irisin concentrations in severely inflamed patients. Horm. Metab. Res. 52 (4), 246–250 (2020).

Funding

This research was funded by Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin, grant number FSN-321-06/23. The APC was funded by Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and I.R.; methodology, A.M. and A.T.-S.; software, A.M. and A.R.; validation, A.R. and A.T.-S.; formal analysis, A.R.; investigation, A.M.; resources, A.M. and A.T.-S.; data curation, A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.; writing—review and editing, A.M. and A.T.-S.; visualization, A.M.; supervision, I.R.; project administration, A.M. and I.R.; funding acquisition, I.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Pomeranian Medical University (protocol code KB-0012/15/2021 of 28 June 2023).

Informed consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mińko, A., Turoń-Skrzypińska, A., Rył, A. et al. Emotional state in patients after COVID-19 in relation to comprehensive rehabilitation, Brain-Derived neurotrophic factor, Irisin levels, and selected clinical factors. Sci Rep 15, 25617 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11389-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11389-w