Abstract

The rapid adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) has driven the continuous evolution of traction systems, necessitating efficiency, reliability, and performance improvements. Conventional motor designs, such as single-stator permanent magnet synchronous machines (PMSMs) and induction motors, often suffer from limited torque density, inefficient thermal dissipation, high torque ripple, and reduced fault tolerance. These challenges hinder optimal EV performance, particularly under varying load conditions. Dual-stator machines (DSMs) have emerged as a promising alternative. They offer higher torque density, improved power distribution, enhanced thermal management, and increased redundancy, making them more resilient to faults. This paper presents a comprehensive mathematical modelling and operational analysis of DSMs, emphasizing their advantages over traditional motor architectures. Furthermore, the Field-Oriented Control (FOC) strategy, a widely adopted method for high-performance motor control, is explored in depth for its suitability in DSM applications. The challenge here is to designate one stator as the primary induction system, ensuring its power is effectively controlled. When the first stator reaches its maximum power capacity, the second stator compensates accordingly. The control design was specifically developed to achieve this objective. MATLAB-based simulations are conducted to assess efficiency, torque response, and fault-tolerant capability, demonstrating the superior performance of DSMs in EV traction systems. The findings highlight the potential of DSMs to redefine next-generation EV propulsion by enhancing power efficiency, reliability, and operational stability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrical machines play a critical role in defining the features and efficiency of electric vehicle systems. In the context of transportation, the selection of driver machines and their characteristics is a decisive factor for the success of any electric vehicle (EV) model1,2. Over time, researchers have explored various machine designs to enhance performance, autonomy, and efficiency. Historically, DC machines were among the first used in EVs but were soon found to have significant limitations regarding autonomy, weight, and overall efficiency3. AC machines were introduced, particularly those based on the induction phenomenon, demonstrating better efficiency and performance. However, their control complexity and limited high-speed range presented challenges, prompting further advancements in electric motor technology4,5. The evolution of electric machines eventually led to brushless designs incorporating permanent magnets within the rotor, providing higher torque density, compact size, and improved performance6,7. However, these designs still faced limitations, particularly regarding system complexity, scalability, and cost-effectiveness8.

Conventional Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines (PMSMs), widely used in EV applications, have several limitations that restrict overall efficiency and system reliability. These limitations include low torque density, which limits power output without increasing motor size, and inefficient thermal dissipation, which leads to excessive heating in stator windings and rotor magnets, reducing efficiency and long-term durability. Additionally, PMSMs exhibit high torque ripple, resulting in vibrations and noise that negatively impact drivability, particularly at low speeds9. Another significant drawback is their reduced fault tolerance, as failures in the winding or inverter can lead to a complete loss of function, making these systems less reliable for demanding EV applications10.

Dual-stator machines have emerged as a groundbreaking solution in EV technology to address these challenges. These machines, characterized by their two independent stator windings, offer numerous advantages, including enhanced power density, better thermal management, and improved fault tolerance.

Dual-stator machines (DSMs) have emerged as a promising alternative, offering significant improvements in motor performance and operational reliability. With their dual-winding architecture, DSMs achieve higher torque density by effectively doubling torque production without increasing current levels, making them well-suited for high-performance EV applications. The improved thermal management in DSMs ensures better heat distribution, reducing localized overheating and enhancing the overall system lifespan. Dual magnetic fields result in smoother flux interaction, minimizing torque ripple and improving overall efficiency, leading to quieter operation and enhanced driver comfort11. Additionally, DSMs provide increased fault tolerance12, as the motor can continue operating even if one stator winding or inverter fails, ensuring greater system resilience. This paper presents a comprehensive mathematical modelling and operational analysis of DSMs, emphasizing their advantages over traditional PMSM architectures.

Furthermore, the Field-Oriented Control (FOC) strategy, a widely adopted method for high-performance motor control, is explored in depth for its suitability in DSM applications. This choice was based on, Previous studies on Field-Oriented Control (FOC) strategies, which have primarily focused on enhancing the dynamic response and overall efficiency of electric drive systems, particularly for electric vehicle (EV) propulsion13. Simulation environments such as MATLAB/Simulink have been extensively used to model and analyze the performance of FOC in controlling Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors (PMSMs)14. The results from these investigations have consistently demonstrated improvements in torque regulation, reduced harmonic distortion, and enhanced system stability15. Additionally, recent research has emphasized the development of sensorless control techniques, employing observer-based algorithms to estimate rotor position and speed16,17. This approach not only reduces system cost but also simplifies hardware implementation. These advancements contribute significantly to the design of robust and efficient FOC strategies that meet the stringent performance demands of modern electric mobility and industrial applications.

MATLAB-based simulations are conducted to assess efficiency, torque response, and fault tolerance, demonstrating the superior performance of DSMs in EV traction systems. The findings highlight the potential of DSMs to redefine next-generation EV propulsion by enhancing power efficiency, reliability, and operational stability.

By leveraging their unique architecture, Dual-stator machines increase the overall performance of EVs and simplify certain design aspects, reducing the dependency on additional mechanical components. In the literature, dual-stator machines have been highlighted for overcoming key limitations of conventional motor designs. They are particularly effective in addressing the challenges of size, power output, torque capability, and cost-efficiency, making them ideal for modern EV applications. This paper explores dual-stator machines’ design, operational principles, and control strategies, providing a comprehensive understanding of their potential in advancing electric vehicle technology. Dual-stator machines are designed to minimize the vehicle’s weight by integrating a second stator instead of relying on a separate electric motor to serve as a generator18,19. These machines are classified as AC machines and typically incorporate permanent magnet materials within, on, or beneath the rotor. Each model features two stator parts equipped with windings, generally forming three-phase coils placed in the stator slots20,21. While the stator structure is consistent across AC machines, the unique Dual-stator configuration introduces complexities in control. Specialized control techniques are required to ensure the independence of parameters such as speed and torque, making managing these machines more challenging.

Objective of the paper

Extensive research and statistical analyses from various publications11,12,13 indicate that adopting a Dual-stator machine provides significant advantages over a standard Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machine (PMSM), particularly in electric vehicle (EV) applications22. One of the primary benefits is space optimization, as the Dual-stator configuration allows for a more compact and integrated drivetrain, freeing up valuable internal space within the vehicle. Beyond spatial efficiency, the dual-stator machine enhances overall system performance. Studies show this architecture contributes to a smoother vehicle design by enabling better power distribution and reducing mechanical constraints14. Additionally, it offers higher available traction power, which is critical for urban mobility and high-efficiency electric drivetrains. Maintenance and servicing are also simplified due to the modular nature of the design, allowing for faster and more accessible interventions than conventional PMSMs. Given these advantages, this study focuses on the design, control, and optimization of the Dual-stator machine for traction applications, aiming to highlight its superiority in efficiency, performance, and adaptability in modern electric vehicle systems. The following sections will provide a detailed analysis of these benefits and the necessary adaptations for real-world implementation.

One of the article’s objectives is to disclose their internal form to determine their operating mode. This is accomplished by analyzing their connected mathematical equations and specifying their associated parameters and variables. However, simply knowing about this type of machine is insufficient because it is extremely tough to operate. Because the control process is dependent on numerous conditions and criteria, such as the requirement for the separation of internal variables. Ensuring the independence of speeds, fluxes, and currents in each type of machine can benefit from a ready-to-use kit for this type of operation. A significant difficulty with the Dual-stator system is that it raises the temperature within the internal rotor and fails to render the control method better than modifying the parameters, such as the stator resistance15,16. As a result, controlling the precise mathematical model that explains the link between the associated parameters.

Since this is a three-phase machine, the control loop is inherently more complex than a DC system. Optimal control strategies, in general, remain an area of active research. Vector control theory highlights the need for precision across a wide speed range compared to conventional control techniques. Several methods were presented, and intelligent controllers and the fuzzy approach were considered suitable, as mentioned in23,24,25. In contrast, adapted controllers, like the model adaptive reference system (MRAS) technique, were assessed for controlling a dual rotor machine, and it was determined that this method had several problems due to the interaction of the two rotor speeds. The works have proved this are26,27. Direct voltage control (DVC) was used to control the Dual-stator machine in generator mode, and the results showed good performance. However, this method is not suggested for use in motor mode. A modified version of the Field Oriented Control (FOC) strategy based on Four-Vector 24-Sector Modulation (FV24SM) and employing the VSD method (Vector Space Decomposition) is suggested in22,23 and determined to minimize the stator current with harmonic components. However, the time calculation approach requires high processor performance, which raises the cost of the global control loop. Another test based on the vector control method was used to manage the same machine, and it produced a low precision response due to the regulator parameters, which require adjustment and optimization28.

Other emerging techniques have been explored to overcome such limitations. Sliding Mode Control (SMC) has shown strong robustness against parameter variations and external disturbances, particularly in electric vehicle traction systems29. Predictive Current Control (PCC) is another promising method that enables fast dynamic response and easy handling of constraints but demands accurate models and high sampling rates30. Reinforcement Learning-Based Control is gaining attention for its capacity to learn optimal policies without explicit system modelling, which is particularly valuable in uncertain or nonlinear environments31. H-infinity Control (H∞) provides a structured way to design controllers that minimize the worst-case gain from disturbances to performance outputs, ensuring robustness in highly dynamic systems32. Lastly, backstepping control, a Lyapunov-based nonlinear control design, is increasingly being applied to electric machines due to its ability to systematically handle system nonlinearities and maintain stability under varying loads33.

All of these control approaches employ multiple PI controllers within the control loop. If not adequately supervised, these regulators can lead to divergence. This causes an unstable stator current and may cause the machine to fail. This is unique inside the twin-stator machine. The FOC control topology was then found to be the most adaptable for the induction machine. Still, it is important to mention that A standard machine employs a single stator and rotor, with the FOC control managing only two current vectors—the direct (d) and quadrature (q) components. Managing these two vectors is relatively straightforward. However, the dual-stator concept requires control over four current vectors—two for each stator. These vectors are strongly interconnected, meaning that if the control strategy is not properly configured, variations can cause undesirable interactions among them. The proposed FOC topology was specifically designed for a dual-stator machine to address all these specifications, setting it apart from the conventional single-stator approach. In this design, one stator is activated within a certain speed range, and the second stator is engaged if that range is exceeded. This is just one of several potential FOC configurations that can be implemented. Importantly, the proposed topology also enhances energy efficiency by minimizing energy losses due to heating from stator resistance.

So, in this version, we suggest a modified FOC operation that considers the active power inside the inner stator to aid in supervising the stator current. Actually, the distinction between the two control loops for double stator and double rotor machines is not entirely evident to readers and researchers. So, one of the goals of this study is to clarify the differences between the two versions and provide the appropriate design for each control approach.

The article begins with an introduction and then analyzes the interaction between electrical machines and electric or hybrid automobiles, focusing on alternative electrical machine interior designs. A separate part discusses the benefits of employing specialized machines such as twin-stator models, demonstrating the gains possible with such designs. The Dual-stator-PMSM model is then detailed, including its mathematical form and the Field-Oriented Control (FOC) method34,35. Simulation results are presented to evaluate and validate the efficiency and robustness of the FOC approach for the Dual-stator-PMSM, proving that each stator can be controlled separately without relying on the other portion. The report finishes with a summary and suggestions for future research topics.

Efficient design and sizing of electric machines for vehicles

Assuming that the relationship between motor power and motor size is nearly linear, it is easy to conclude that as power increases, so does motor size. Based on this knowledge, it is certain that the vehicle size for the three listed examples will be larger than the others. Using the new architectures of electrical machines, which guarantee especially a high torque (the permanent magnet machine), it is possible to ensure the same traction performance or recharge mode as it characterizes the previous architecture, using the double rotor machine36, and the double stator machine37,38. The two-stator machine has twice the mechanical power of the simple architecture since it can be agitated twice.

Table 1 compares the dual-stator and simple design of PM machines that can be employed for traction and power generation in hybrid car architectures or wind power applications39. These statistics are related to the required power, which is 100 kW. Two basic PM machines or one dual-stator machine can ensure this power margin. Combining these two motors will take up 10.5 L of empty space inside the automobile and weigh 250 kg. However, when utilizing the twin stator version, the required space will be less than 25% of the first instance, and the weight will be less than that of the first case.

Because these machines offer the advantages mentioned above, it is necessary to understand the internal mathematical model of each version to control them. As a result, the following sections provide a complete mathematical analysis of each version and describe how each model might be applied in the transportation system.

The interior design of both the single-stator and dual-stator machines is illustrated in Fig. 1. Figure 1a presents the dual-stator configuration, which requires using dual converters for operation. In contrast, Fig. 1b depicts the single-stator machine, where only one converter is needed, as it consists of a single three-phase coil housed within a single stator. Unlike the dual-stator machine, which necessitates a more complex converter setup, the single-stator design operates with a simplified electrical structure.

Dual-stator single-rotor permanent magnet machine (DSM)

Interior design of the dual-stator machine

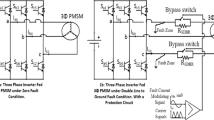

Dual-stator permanent magnet machines are still widely utilized for traction applications due to their high performance and integrated design23. This machine type was proven acceptable for usage inside the vehicle’s wheels. This design can produce high torque when required, particularly in certain acceleration situations. It can be employed within a HEV or EV, and the mechanical power output from this motor can reach two high levels. However, this machine can also function as a second generator, powering some auxiliary electric components or charging the battery box. As a result, this machine can come in two different designs. The first design includes a bigger stator that is used to power the vehicle’s main traction motor using a power converter. The second component contains the lower stator, which will power the battery system via another rectifier. The second design uses two stators to provide electromagnet force for a single rotor. Figure 2 depicts the second design, in which two separate converters provide electric power to the two stators. Figure 2 depicts the identical equipment, which is being used to demonstrate stators and rotor designs from another angle. This machine has one rotor with magnets. This rotor is located between the two stators, denoted as the outer stator and the inner stator20.

Modelling of the dual-stator machine

The quantitative formulation of this model involves identifying the voltage equation system, as illustrated in equation system (1).

Vs, R, I, and ø represent the stator voltage, resistance, current, and flux for each phase “a”, “b”, and “c” in the first and second stators, denoted by “j”. We assume that the resistance of the Dual-stator is equivalent. In Eq. (2), we present the flux equation system. All the internal matrices and vectors are cited in Eqs. (2a) to (2f).

The translation of the equation system revealed in (1) to the Park model is implied in the equation systems (3a) and (3b). Based on the park frame, the flux equations are summarized in Eq. (4).

Based on this reduction, the mechanical equations for this system are as shown in Eq. (5).

It is important to note that the form of the motor torque is variable, and this part can be produced using simply the stator’s first components, as shown in Eq. (6). However, it can also be stated regarding additional secondary stator winding currents, as shown in Eq. 7.

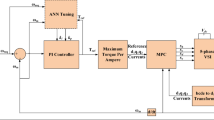

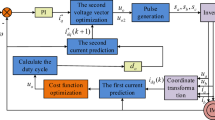

Adapted field oriented vector control

Referring to previous works, various control architectures have been applied to induction machines, primarily for achieving simple motor control objectives. Table 2 presents the major control techniques adapted for induction machines. Many of these techniques have been further developed to address the control challenges of dual-stator machines. One such adaptation is the dual-stator FOC approach, which extends the conventional Field-Oriented Control (FOC) design originally developed for single-stator induction machines. The proposed FOC control method is based on the traditional FOC framework but is modified to regulate active and reactive power within one stator, while the second stator is controlled independently using the conventional FOC strategy. The overall control scheme is summarized in Fig. 3.

Conventional control systems for typical alternating current machines, such as Direct Torque Control (DTC) or Field-Oriented Control (FOC), have been widely explored in numerous references, just like for any other induction machine48. While managing a Dual-stator machine may appear simple, comprising independent control of each stator, the system must consider special constraints. The system must operate under a single reference speed, and six reference signals must be measured. This methodology is more sophisticated than typical methods, which use a single reference speed to generate three reference signals for a single stator. As a result, the control architecture must follow an organized procedure. The first step is to define the relationship between the stators’ winding angles and the mechanical angle, as shown in Eq. (8). Consequently, Eq. (9)

The primary or secondary stator can be powered by either AC or DC electricity. When a DC current flows through one of the stators, its corresponding electrical angular position becomes zero, simplifying the control procedure. However, this research focuses on the AC excitation approach. The control procedure is based on a fundamental principle that demands the primary stator’s reference currents as well as the rotor’s reference speed. Equations (8) and (9) are used to derive the secondary stator’s reference frequency and angle. With this information, current vectors may be precisely positioned in the “dq” reference frame. The necessary voltage vectors are then generated using PI controllers and translated into the “abc” reference frame.

Equations (5) and (7) derive the reference currents, with the reference torque determined by the reference speed. This torque is defined in terms of the secondary stator’s direct and quadrature (transversal) currents and the primary stator’s flux components. The primary flux, in turn, is defined by the primary winding current. Given the intricacy of this equation, the control strategy assumes that the direct current components are zero and focuses solely on the quadrature current components. Consequently, decoupling the torque equation becomes crucial.

The two inverters operate separately. Equation (10) describes the power output from the primary inverter, with the maximum output being a known value.

The reactive power equation can be resumed in Eq. (11). The active power equation can be formed as in Eq. (12)

Therefore, employing Eq. (10), we can compute the primary winding’s transversal reference current. As a result, the final control scheme for this machine will be as shown in Figure 3a.

Remark

In the control system, if Eq. (6) rather than (7) is employed, the coupling effect is eliminated, and each stator is regulated separately. This is not applicable in an electric vehicle because the machine must not switch on if the reference speed is set to zero. In this case, the machine will have a mechanical speed equal to \({\omega _{s,1}}\). This is an input reference set to 50 Hz in general.

Figure 3b illustrates the general control architecture of an electric vehicle (EV), starting from the driver’s command, which generates a speed reference signal. This reference is processed by the control system to determine the required torque and speed of the electric machine. The Field-Oriented Control (FOC) strategy is implemented within the block that controls the electric machine, acting as the core of the motor control loop. It processes the speed reference, estimates rotor position (or receives it from sensors), and regulates the stator current components to achieve precise torque and flux control. The output of the FOC generates voltage references for the power converter (inverter), which drives the electric machine accordingly. The electric machine then interacts with the vehicle dynamics/load, completing the drivetrain loop. The battery management system (BMS) monitors and controls energy flow between the power converter and battery, ensuring safe and efficient power delivery throughout the system.

Application and results

In this section, we intend to verify and validate the efficacy of the FOC techniques. As a result, we have integrated the machines and their control loops into two specialized applications. The applications were based on the machine specifications listed in Table 3. The remaining portion of this section contains a more detailed description of the tests used.

To assess the effectiveness of the FOC method in managing the DSSRPM, the machine’s model was evaluated in a simulated environment on the MATLAB platform. In this simulation, the DSSRPM was used during the traction phase to provide the vehicle with the necessary traction power. The machine has a single rotor; therefore, only one speed needs to be maintained. However, when two stators are present, two stator currents and their associated electric powers are tracked. The machine is controlled by a specific control block that manages the vehicle’s speed using two stators. Figure 4a depicts the vehicle speed, using this type of motor motor, under an applied acceleration form as it is in Figure 4b, whereas Figure 5 compares the reference motor speed profile to the observed motor speed profile. These findings support the FOC strategy’s precision and effectiveness. Small delays in the speed response, as shown in the zoomed-in parts, can be reduced by tweaking the PI controller parameters. The control loop handles both stators based on motor speed and the first stator’s maximum supported power, which is set to 10 kW. As a result, the stator currents represented in Figure 6 reveal that the maximum current in the first stator is 20 A. Beyond this threshold, the second stator is activated, with the current peaking at 60 A. The findings show that the two stator currents run independently, confirming the effectiveness of the FOC technique for this machine type. Figure 7 shows the total motor powers, which delineate each stator’s operating zones.

The dynamic performance of the Dual-stator Machine (DSM) has been thoroughly analyzed through its speed, power, and stator current behaviours during the acceleration and deceleration phases. The speed response exhibits a rapid increase from standstill to approximately 5000 rpm, achieving a settling time of less than 2 s with an overshoot limited to around 6% relative to the reference speed. This confirms the system’s responsiveness and stability. Initially, the first stator provides the required torque, with its current peaking at 30 A, while the motor power reaches 10 kW. Upon crossing 5000 rpm, the second stator engages seamlessly, scaling the motor power up to 40 kW. The second stator current takes dominance, ensuring the motor meets high-speed and high-torque demands efficiently. The transition between stators is well-managed, with no significant disturbances observed in speed or power profiles, and the speed tracking error remains below 2% during steady-state operation. During deceleration, both power and current diminish proportionally, and the motor maintains stability without oscillations, ensuring smooth operation. The adaptive current sharing between the stators also enhances thermal balance, minimizing the risk of localized overheating. Overall, the DSM demonstrates robust control dynamics, managing both acceleration and deceleration phases effectively, with quantitative indicators confirming fast response and minimal overshoot. This comprehensive dynamic analysis complements steady-state evaluations, providing a holistic view of motor performance and ensuring suitability for demanding applications like electric vehicles, where dynamic responsiveness is critical.

Figure 8 illustrates the evolution of direct and transversal flux in two different scenarios: when only one stator is active and when both stators are simultaneously energized. Since the primary active stator is the first one, its corresponding flux is expected to be close to unity in the main stator, as shown in Figure 8b, while it remains nearly null in the second stator, which is inactive. Figure 8c depicts the flux in the second stator when it is turned off. The recorded value is approximately 10⁻¹⁷, indicating that the existing flux is primarily due to the magnetic reaction from the first stator. These results confirm the effectiveness of the proposed control approach, as it ensures the decoupling of the magnetic flux between the two stators. When both stators are activated, the second stator, operating outside its optimal range, exhibits a flux pattern resembling a circular shape, as shown in Figure 8d. In this case, the second stator operates alongside the first stator, which maintains the behaviour depicted in Figure 8a. Consequently, the total flux within the machine approximates the sum of the fluxes generated by both stators. The results confirm the independence of the flux in each stator, as evidenced by the well-defined circular flux pattern, particularly when both stators are active. The only instance of flux imbalance occurs in the second stator when it is off, which does not pose any operational drawbacks to the machine. These promising performance results highlight the robustness of the proposed control strategy.

The FOC control method was developed and tested specifically for the twin stator machine, yielding outstanding results in speed tracking with minimal disturbances during transitions, owing mostly to the non-optimized PI controller parameters. Because these values were calculated using traditional calculation methods, using intelligent techniques for parameter optimization is strongly advised to improve performance. Despite this constraint, the control approach efficiently maintains the independent operation of the two stator currents, considerably increasing the efficiency and versatility of the Dual-stator machine for complicated applications like robotics and other specialized activities49. Table 4 summarizes the strengths and limits of the FOC control technique when applied to Dual-stator machines, highlighting its advantages over typical machine setups.

Limitations on DSM

The adaptation of Field-Oriented Control (FOC) to DSM introduces several technical challenges and limitations that differentiate it significantly from conventional three-phase implementations. One of the primary concerns is the increased control complexity. DSM possess additional degrees of freedom that must be managed using extended mathematical models. The traditional d–q transformation is no longer sufficient; instead, the control system must decompose the stator currents into multiple orthogonal subspaces, typically d–q, through advanced Clarke and Park transformations. This significantly raises the computational burden on the digital signal processors (DSPs) or microcontrollers responsible for real-time control. Another limitation arises from the presence of low-order spatial harmonics in these additional subspaces, which can induce torque pulsations and reduce overall system efficiency. Standard FOC schemes, which primarily target the fundamental d–q subspace, are not inherently designed to suppress these harmonic effects, requiring additional compensation techniques. Sensorless control in this system is also more challenging due to the increased complexity of accurately estimating rotor position and speed. Observer-based approaches must account for the interactions between harmonic planes, which can degrade the estimation quality under varying load and speed conditions. Furthermore, implementing FOC for DS machines entails higher hardware costs, as the system requires more inverter legs, sensors, and processing capabilities compared to their three-phase counterparts. Finally, while DS machines are inherently more fault-tolerant, conventional FOC strategies do not fully exploit this benefit. Under fault conditions such as open-phase or unbalanced operations, significant modifications to the control strategy are required to maintain performance. These limitations highlight the need for more advanced control algorithms and robust hardware design to fully leverage the potential of DSM in high-performance and fault-tolerant applications.

Heat analysis and thermal effect on the DSM

Heat analysis for the DSM and SSM

When comparing Dual-stator induction machines (DSMs) and single stator induction machines (SSIMs) regarding thermal management, DSMs offer notable thermal advantages. In DSMs, the thermal load is evenly distributed across two stator windings, significantly reducing current density and copper losses in each stator. This leads to lower hotspot formation and enhances the machine’s thermal stability and reliability, especially under high-power conditions. In contrast, SSMs concentrate all thermal stresses within a single stator, resulting in higher heat fluxes and requiring more robust cooling systems to prevent overheating. Although the SSIM’s cooling design is mechanically simpler, it must handle more intense localized heating, often demanding increased airflow or coolant circulation. DSMs, despite their more complex cooling requirements (as they involve two stators), benefit from reduced heat per unit area in each stator, allowing for more efficient thermal control .

Additionally, the shared thermal load in DSMs contributes to improved efficiency and extended lifespan of the machine components. However, DSMs may experience higher rotor core losses due to the interaction of two stator fields, necessitating careful rotor cooling design. Overall, the primary thermal advantage of DSMs lies in their ability to mitigate thermal stress effectively, making them more suitable for high-power density applications where managing heat generation is critical to maintaining performance and reliability. Table 5 can give an estimation for thermal metrics for the two kind of machine for a similar power range (50 Kw).

Heat performances with the motor speed

In the Dual-stator Machine (DSM), the observation that the overall motor temperature remains lower than the first stator temperature during low-speed operation is consistent with the machine’s thermal management design. Only the first stator is active at lower speeds, supplying the required torque, which leads to localized heating within that stator winding. In contrast, the second stator remains inactive during this phase, contributing negligible heat and effectively acting as a heat sink. The overall motor temperature is typically calculated as the average of the two stator temperatures, so even if the first stator reaches elevated temperatures (e.g., 50–55 °C), the cooler second stator (e.g., 30 °C) lowers the combined thermal reading. This thermal averaging effect ensures that the overall temperature remains moderate, reducing the risk of hotspot formation. This design strategy enhances thermal efficiency and system longevity, preventing excessive thermal stress on any single stator. Once the motor transitions to higher speeds, the second stator engages, sharing the load and distributing the thermal generation more evenly. This adaptive stator activation strategy ensures optimal thermal behavior across different speed ranges, supporting efficient operation and improved reliability of the DSM under varying load conditions. This can be shown in Fig. 9.

The overall motor temperature (T_motor) is calculated as the weighted average of the temperatures of the two stators based on their power contributions (13):

where T_motor = Overall motor temperature; T1 = First stator temperature; T2 = Second stator temperature; P1 = Power contribution of the first stator; P2 = Power contribution of the second stator.

During low-speed operation, only the first stator is active (P1 ≠ 0, P2 ≈ 0), simplifying the equation to:

However, due to thermal conduction and ambient cooling affecting the inactive stator, a simplified average can be used:

With T2 near ambient temperature (e.g., 30 °C) and T1 elevated (e.g., 50–55 °C), the overall motor temperature remains lower than T1. This confirms the observed thermal behavior, where thermal balancing between the two stators prevents localized overheating and ensures efficient operation across varying speed ranges.

Heat effect for the DSM

One of the significant challenges affecting the robustness of electric machines is related to the heat dissipation and cooling methods, which can significantly impact the machine’s stator performance. It is well known that as the temperature increases, the stator resistance also rises, directly affecting the Field-Oriented Control (FOC) strategy. Since the FOC design relies on accurate motor specifications, particularly the stator resistance used in the PI controller tuning, any variation in this parameter can lead to performance degradation. Specifically, equations (3a, 3b, and 12) in the control design incorporate the stator resistance, meaning that changes in this parameter can render the existing PI controllers ineffective, compromising the stability and precision of the FOC. As a result, the designed FOC method may lack sufficient robustness under varying thermal conditions. A modified FOC approach with online PI parameter adjustment is required to address this issue and compensate for the resistance changes. Various adaptive methods have been proposed in the literature to enhance control performance under such scenarios. Notably, one relevant study was published by the same research team, offering a foundation for further improving the proposed control strategy53.

Future endeavours

The proposed control approach has demonstrated promising results in ensuring the decoupling and independent operation of the dual-stator flux, highlighting its robustness and effectiveness. However, future work will focus on the experimental validation of the proposed methodology. The unique configuration of the designed machine, featuring a dual-stator topology with one stator enclosed within another, presents manufacturing challenges that necessitate specialized construction. Currently, efforts are directed towards the mechanical research team’s fabrication and validation of the machine. Once the physical prototype is realized, comprehensive testing will be conducted to assess the real-time performance of the control strategy, incorporating advanced measurement techniques and power electronic converters. This validation phase will enable further refinement of the control framework, addressing potential implementation constraints and optimizing system efficiency. Additionally, future research will explore the integration of fault-tolerant strategies and adaptive control mechanisms to enhance the machine’s reliability and operational flexibility54,55. The anticipated experimental results will provide valuable insights into the practical feasibility of the proposed approach, paving the way for further advancements in multi-stator machine control and expanding its applicability in high-performance electromechanical systems.

On the other hand, several key areas for future research and development can be identified, such as Controller Optimization – Implementing Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) or other metaheuristic algorithms to enhance response time and efficiency in real-world conditions56. Adaptive Control Strategies – Develop real-time motor parameter estimation techniques, such as Model Reference Robust Adaptive Control (MRRAC) or Model Reference Adaptive System (MRAS), to improve adaptability under varying loads and environmental conditions. Dynamic Parameter Adjustment – Using online optimization methods to fine-tune control parameters dynamically, reducing system inefficiencies. Advanced Thermal Management Solutions – Investigating liquid cooling techniques or heat pipe integration to mitigate thermal constraints57.

Conclusion

This study explores the Dual-stator synchronous permanent magnet machine, a specialized electrical machine designed for urban transportation applications, particularly in two- and four-wheel vehicles. A comprehensive mathematical analysis of the machine is conducted to develop an optimized control architecture that enhances performance and operational efficiency. The control strategies for the Dual-stator machine are developed using the Field-Oriented Control (FOC) methodology and validated through MATLAB simulations. While the proposed design demonstrates improved power distribution, torque ripple reduction, and enhanced fault tolerance58,59, certain limitations still exist to have a perfect situation. The limitations can be cited as:

Compared to traditional single-stator designs, dual-stator machine require additional power electronics, increasing cost and overall system weight. While the dual winding structure offers notable thermal advantages, such as improved heat dissipation and higher power density, the cooling system design becomes more complex thanks to the thermal crossover between the two stator windings. Additionally, the motor’s internal configuration can present construction challenges due to the intricate arrangement of the Dual-stators.

Data availability

Data are available from corresponding authors on request.

References

Pei, J. Z., Su, Y. X. & Zhang, D. H. Fuzzy energy management strategy for parallel HEV based on pigeon-inspired optimization algorithm. Sci. China Technol. Sci., pp. 1–9, (2016).

Wang, Z., Wang, S., Wang, X. & Luo, X. Permanent Magnet-Based superficial flow velometer with ultralow output drift. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 72, 1–12 (2023).

Ulatowski, A. & Bazzi, A. M. A Combinational-Logic method for electric vehicle drivetrain fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 52 (2), 1796–1807 (2016).

Abraham, P. K. & Ashok, S. Design and implementation of an efficient regenerative braking system for a vector controlled PMSM drive, 2016 3rd International Conference on Electrical Energy Systems (ICEES). pp. 312–317, (2016).

Koohi, I. & Groza, V. Z. Optimizing Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm, 2014 IEEE 27th Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE). pp. 1–5, (2014).

Un-Noor, F., Padmanaban, S., Mihet-Popa, L., Mollah, M. N. & Hossain, E. A comprehensive study of key electric vehicle (EV) components, technologies, challenges, impacts, and future direction of development. Energies 10 (8), 1–82 (2017).

Fang, L., Li, D. & Qu, R. Torque improvement of Vernier permanent magnet machine with larger rotor pole pairs than Stator teeth number. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 70 (12), 12648–12659 (2023).

Brooker, A., Thornton, M. & Rugh, J. Technology Improvement Pathways To cost-effective Vehicle Electrification ( SAE Tech. Pap, 2010).

He, D. et al. Research on vertical vibration characteristics of rolling mill based on magnetorheological fluid damper absorber. Mech. Syst. Signal. Process. 224, 112203 (2025).

Zhang, R. et al. An asymmetric hybrid Phase-Leg modular multilevel converter with small volume, low cost, and DC Fault-Blocking capability. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 40, 5336–5351 (2025).

Chen, C., Wu, X., Yuan, X. & Zheng, X. Prediction of magnetic field for PM machines with irregular rotor cores based on an enhanced conformal mapping model considering magnetic-Saturation effect. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 11 (1), 2516–2528 (2025).

Hang, J., Wang, X., Li, W. & Ding, S. Interturn Short-Circuit fault diagnosis and fault-Tolerant control of DTP-PMSM based on subspace current residuals. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 40, 3395–3404 (2025).

Lu, Y., Jiang, Z., Chen, C. & Zhuang, Y. Energy efficiency optimization of field-oriented control for PMSM in all electric system. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 48, 101575 (2021).

Megrini, M., Gaga, A., Mehdaoui, Y. & Khyat, J. Design and PIL test of extended Kalman filter for PMSM field oriented control. Res. Eng. 24, 102843 (2024).

You, Z., Bian, Y., Zhang, Y. & Chen, L. An intelligent optimization algorithm with novel fitness function for high-performance PMSM FOC. Alex. Eng. J. 115, 286–296 (2025).

Usha, S. et al. Performance enhancement of sensorless induction motor drive using modified direct torque control techniques for traction application. Alex. Eng. J. 108, 518–538 (2024).

Ramesh, P., Umavathi, M., Bharatiraja, C., Ramanathan, G. & Athikkal, S. Development of a PMSM motor field-oriented control algorithm for electrical vehicles. Mater. Today Proc. 65, 176–187 (2022).

Rizuan, S. et al. Modeling and analysis of double Stator slotted rotor permanent magnet generator. Energies 10 (411), 1–16 (2017).

Liu, C., Chau, K. T., Zhong, J., Li, W. & Li, F. Quantitative comparison of double-stator permanent magnet Vernier machines with and without HTS bulks. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond, 22, 3, (2012).

Dikshit, U. C. & Tripathi, R. K. Direct torque control for dual three-phase induction motor drives. In 2012 Students Conf. Eng. Syst. SCES 2012. (2012).

Luo, Y., Liu, C., Yu, F. & Lee, C. H. T. Design & evaluation of an efficient three-phase four-leg voltage source inverter with reduced IGBTs. Energies, 10, 4, (2017).

Jiang, J., Niu, S., Zhao, X. & Fu, W. N. A novel winding switching control strategy of a Consequent-Pole Ferrite-PM Hybrid-Excited machine for electric vehicle application. IEEE Trans. Magn. 58 (2), 1–5 (2022).

Flah, A., & Novák, M. N. Estimation of motor parameters for an electrical vehicle application. Int. J. Model. Identif. Control. 22 (2), 150–158 (2014).

Gadoue, S. M., Giaouris, D. & Finch, J. W. Stator current model reference adaptive systems speed estimator for regenerating-mode low-speed operation of sensorless induction motor drives. IET Electr. Power Appl. 7 (7), 597–606 (2013).

Flah, A., Novak, M., Sbita, L. & Novak, J. Online PMSM parameters estimation for 32000 rpm, in CEIT-13, pp. 148–152. (2013).

Saad, N. H., El-Sattar, A. A. & Gad, M. A. Sensorless Field Oriented Control based on improved MRAS speed observer for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor drive. In 2016 Eighteenth International Middle East Power Systems Conference (MEPCON). pp. 991–998, (2016).

Flah, A., Novak, M. & Lassaad, S. An improved reactive power MRAS speed estimator with optimization for a hybrid electric vehicles application. ASME J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control. 140 (6), 061016 (2018).

Ullah, F. et al. A comprehensive review of wind power integration and energy storage technologies for modern grid frequency regulation. Heliyon 10 (2023).

Li, K., Ding, J., Sun, X. & Tian, X. Overview of sliding mode control technology for permanent magnet synchronous motor system. IEEE Access. 12, 71685–71704 (2024).

Schwenzer, M., Ay, M., Bergs, T. & Abel, D. Review on model predictive control: an engineering perspective. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 117 (5), 1327–1349 (2021).

Rossi, F., Gruosso, G. & Gajani, G. S. A Reinforcement Learning based controller for optimal speed control of a DC motor using deep Q-network algorithm. In IEEE EUROCON 2023–20th International Conference on Smart Technologies, pp. 181–186. (2023).

Messirdi, M., Abdelmadjid, B. & Oudjamaa, F. New approach for nonlinear robust H-Infinity control of an induction motor. J. Control Autom. Electr. Syst. 34 (4), 743–751 (2023).

Trabelsi, R., Khedher, A., Mimouni, M. F. & M’sahli, F. Backstepping control for an induction motor using an adaptive sliding rotor-flux observer. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 93, 1–15 (2012).

Njajra, Z., Elhak Chariag, D., Ayman, F. & Sbita, L. Model reference adaptive sliding mode control for permanent magnet double rotor motor. J. Autom. Syst. Eng. 11 (1), 45–55 (2017).

Ahmed, S. et al. A modified Multi-Level inverter system for Grid-Tied DES applications. Sustain 14 (16545), 1–16 (2022).

Xiao, R., Yang, X., Zhu, W. & Cao, J. Modeling and simulation of dual-rotor permanent-magnet synchronous motor based on MATLAB. In Proc. – 12th Int. Conf. Electr. Mach. Syst. ICEMS , pp. 1–4 (2009).

Salihu, S. M., Misron, N. & Mariun, N. A Novel Double-Stator Permanent Magnet Generator Integrated with a Magnetic A Novel Double-Stator Permanent Magnet Generator Integrated with a Magnetic Gear, profgress. Electromagn. Res. 49, 69–80 (2016).

Ogunjuyigbe, A. S. O., Ayodele, T. R. & Adetokun, B. B. Modelling and Analysis of Dual-stator-Winding Induction Machine using Complex Vector Approach Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal Modelling and analysis of Dual-stator-winding induction machine using complex vector approach. Eng. Sci. Technol. an Int. J. 21, 351–363 (2018).

Kong, Y., Wang, T. & Chu, F. Meshing frequency modulation assisted empirical wavelet transform for fault diagnosis of wind turbine planetary ring gear. Renew. Energy. 132, 1373–1388 (2019).

N, V. N., Singh, S. P. & Panda, A. K. An interval Type-2 Fuzzy-Based DTC of IMD using hybrid duty ratio control. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 35 (8), 8443–8451 (2020).

Krzysztofiak, M., Skowron, M. & Orlowska-Kowalska, T. Analysis of the impact of stator inter-turn short circuits on Pmsm drive with scalar and vector control. Energies, 14, 1 (2021).

Sha, C., Luo, J. & Ziabari, M. T. A new robust decentralized approach based on adaptive fuzzy backstepping method for microgrid secondary voltage control. Sustain. Energy Grids Networks. 27, 100487 (2021).

Mohanty, S. et al. A novel electric spring with improved range of operation for isolated microgrid systems. IEEE Access. 75761–75781, (2023).

Rong, Q. et al. Virtual external Perturbance-Based impedance measurement of Grid-Connected converter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 72 (3), 2644–2654 (2025).

Wang, F. et al. Prescribed performance adaptive robust control for robotic manipulators with fuzzy uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 32 (3), 1318–1330 (2024).

Jasim, A. M., Jasim, B. H., Alhasnawi, B. N., Flah, A. & Kraiem, H. Coordinated Control and Load Shifting-Based Demand Management of a Smart Microgrid Adopting Energy Internet. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 6615150 (2023).

Mehedi, F., Taleb, R., Djilali, A. B. & Yahdou, A. SMC based DTC-SVM control of five-phase permanent magnet synchronous motor drive. Indones J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 20 (1), 100–108 (2020).

Jiang, J., Niu, S. & Zhang, X. Torque improvement of a Hybrid-Excited Vernier reluctance machine with High-Order-Harmonic winding design for electric vehicle application. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 10 (2), 2397–2407 (2024).

Gao, J. et al. Design and optimization of a novel Double-Layer Helmholtz coil for wirelessly powering a capsule robot. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 39 (1), 1826–1839 (2024).

Zhao, A., Zanuso, G. & Peretti, L. Transient thermal models of induction machines under Inter-turn short-circuit fault conditions. IET Electr. Power Appl. 17(10), 1304–1320 (2023).

Roy, R., Ramasami, S. & Chokkalingam, L. N. Review on thermal behavior and cooling aspects of axial flux permanent magnet Motors–A mechanical approach. IEEE Access. 11, 6822–6836 (2023).

Madhavan, S. et al. Thermal management analyses of induction motor through the combination of air-cooling and an integrated water-cooling system. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 10125 (2023).

Alrashed, M., Elnaggar, M. F., Flah, A. & El-Bayeh, C. Z. Online intelligent parameter and speed Estimation of permanent magnet synchronous motors using bacterial foraging optimization. Sci. Technol. Energy Transit. 80, 1–19 (2025).

Hang, J., Qiu, G., Hao, M. & Ding, S. Improved fault diagnosis method for permanent magnet synchronous machine system based on lightweight multisource information data layer fusion. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 39, 13808–13817 (2024).

He, W., Hang, J., Ding, S., Sun, L. & Hua, W. Robust diagnosis of partial demagnetization fault in PMSMs using radial Air-Gap flux density under complex working conditions. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 71 (10), 12001–12010 (2024).

Zou, Z., Yang, S. & Zhao, L. Dual-loop control and state prediction analysis of QUAV trajectory tracking based on biological swarm intelligent optimization algorithm. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 19091 (2024).

Zheng, J. et al. Flight verification of cooling self-sustaining high-temperature superconducting motor. Supercond Sci. Technol. 37 (7), 07LT02 (2024).

Li, J., Wu, X., Wu, L., Computationally-Efficient, A. & Analytical model for SPM machines considering PM shaping and property distribution. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 39, 1034–1046 (2024).

Zhi, S., Shen, H. & Wang, T. Gearbox localized fault detection based on meshing frequency modulation analysis. Appl. Acoust. 219, 109943 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for funding this research work through the project number (PSAU/2024/01/32001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contribute equalliy in this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elnaggar, M.F., Flah, A., El-Bayeh, C.Z. et al. Optimized FOC control strategy for dual stators permanent magnet machine. Sci Rep 15, 34010 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11435-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11435-7