Abstract

Tactile illusion is a promising concept for navigation, sensory augmentation for assistance, virtual reality (VR), and mobile haptic interaction applications enabling efficient feedback with a limited number of actuators. Through the funneling illusion, directional cues can be generated using a tactor array-based system, transmitting cues even at locations where actuators are not physically mounted. This technique has been applied to various research objectives according to modality, mapping methods, body part, and other factors. Accordingly, experimental studies analyzing the perceptual characteristics of the funneling illusion mapping methods across different modalities are necessary. We examined the effectiveness of funneling illusion mapping methods using vibrotactile and electrotactile modalities on the trunk and shank. The study involved two types of experiments, circle tracking (continuous cue) and directional accuracy (discrete cue) experiments with 20 healthy participants. The experimental results showed that for the electrotactile modality, Power law-based mapping provided the most accurate and continuous cue on the shank for both cue types. Square and Power law-based mappings provided the most accurate and continuous cue on the trunk during the circle tracking experiment. For the vibrotactile modality, Linear mapping provided the most accurate and continuous cues during the circle tracking experiment. These results demonstrate that mapping method performance varies across experimental conditions. Our findings can guide the selection of experimental parameters when utilizing a tactor array-based system for the trunk and shank.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tactile feedback can provide effective cues by transmitting sensation along the skin with minimal interference to daily activities. Additionally, it offers advantages in terms of weight and size for transmitting sensations1,2. It provides sensory information via mechanical or electrical tactile actuators, which are perceived by receptors in the skin3,4. Vibrotactile feedback (VTF) systems have been actively researched due to their diverse applications in rehabilitation training or navigation for blind people5,6,7,8,9. The efficacy of VTF may be reduced by decreased skin sensitivity under muscle fatigue, which can easily occur during training or daily activities1,10. However, electrotactile feedback (ETF) can effectively provide sensation under muscle fatigue1. In addition, ETF has also been reported to provide more localized sensations11, silent operation, and low power consumption12. In this regard, electrotactile feedback (ETF) is a viable alternative to VTF.

These tactile feedback systems can be implemented using surrounding circular array-type actuators to provide feedback. A trunk-mounted tactor array can provide cues as biofeedback for balance during standing5, sitting13, or gait8 in individuals with vestibular deficits, helping to improve balance and facilitate rehabilitation training by preventing imbalance caused by balance disorders. Afzal et al. utilized vibrotactor arrays to provide biofeedback to improve gait symmetry in stroke survivors during the swing phase of gait2,14. Likewise, tactile biofeedback systems can support rehabilitation training tailored to individual symptoms such as balance deficits, asymmetry, and other impairments. In addition, tactile systems can be utilized as navigation aids for blind users. Katzschmann et al. applied a vibrotactor array and infrared sensor array system to the trunk of blind individuals, providing feedback about surrounding obstacles and guiding direction through vibration patterns. Through this system, blindfolded individuals reached their destination faster compared to when using a cane6. Liao et al. utilized a vibrotactor array on the shank to guide users toward a goal area and it was as effective in guiding the user, comparable to providing visual feedback of the goal position7.

However, in tactile actuator array-based systems, the size of actuators and the two-point discrimination capability of humans restrict the number of cues that can be provided to users15. Thus, the resolution for directional feedback is limited. To provide efficient feedback with a limited number of actuators, tactile illusion has been utilized as a promising concept for blind navigation7,16,17, sensory augmentation for assistance1,18,19,20,21, virtual reality (VR)22,23,24,25, and mobile haptic interaction26,27 applications. In particular, navigation and rehabilitation applications mostly apply tactor systems to the shank1,7 or trunk19,20, while VR and mobile haptic interaction studies apply them to hands22, fingers23,26,27, forearms25, or face24. Tactile illusions are generated by actuating two or more actuators using amplitude modulation (funneling), time delay (saltation), or overlapping (tactile apparent motion). Through these tactile illusions, tactile perception can occur even in areas where actuators are not directly attached to the skin22,23. Tactile apparent motion focuses on the movement of sensation and is suitable for continuous information transmission (trajectory), such as in navigation applications16,17. The funneling illusion utilizes simultaneous actuator activation and can generate immediate and continuous information transmission by adjusting the amplitude of actuators7,17,28.

Related works: Funneling illusion mapping methods

Various mapping methods have been applied for the vibrotactile funneling illusion to accurately target desired stimulation points. Funneling illusion mapping methods differ in how they modulate the intensity provided by adjacent actuators. Alles proposed the funneling illusion with Linear and Logarithmic mappings, which modulate actuators’ intensity linearly and logarithmically, respectively, according to the position of the illusion using two vibration motors mounted on the upper arm29. In that study, Logarithmic mapping provided more uniform sensation than Linear mapping. Israr et al. proposed Square mapping, which modulates actuator intensity according to the square root of the illusion position to control the location of the funneling illusion while using a grid distribution of vibrotactile actuators30. They confirmed that Square mapping provided a more accurate illusional sensation than Linear and Logarithmic mappings. In addition, Schafer et al. reported the intuitiveness for guiding wrist angle while using Square mapping based on a forearm-mounted 4-vibrotactor array31. However, Lin et al. successfully generated funneling illusion with Linear mapping using array-type actuator placement on the forearm25. Additionally, Yun et al. utilized perceived intensity-based Linear and Gaussian mappings (PI-Linear, PI-Gaussian) which are based on perceived intensity to move the funneling illusion over large distances from the upper back to the thigh. The perceived intensity of each body site was pre-measured, and standardized parameters were applied for each participant. They confirmed that considering perceived intensity can compensate for the differences in sensitivity across body sites32. Recently, Luo et al. utilized Linear mapping to generate the funneling illusion from the palm to finger (1D) and at arbitrary locations on the hand (2D) based on a 6 CH vibrotactor system mounted on the palm (1 CH) and fingers (5 CH)33.

Compared to vibrotactile feedback, there has been less research on the electrotactile funneling illusion. Izumi et al. conducted a preliminary study on electrotactile funneling illusion to provide realistic sensory feedback to spinal cord injury patients regarding the status of their fingers by employing Linear and Square mappings. They confirmed that Square mapping provided more equisensational contours compared to Linear mapping18. Pfeifer et al. utilized Linear and Logarithmic mappings to transmit center of pressure information for prosthetic limbs. There were no clear differences between Linear and Logarithmic mappings19. In our previous work, we demonstrated Power law-based mapping to provide information on standing postural balance while using an electrode pad array system1. Power law-based mapping modulates the perceived intensity of actuators linearly, with each intensity individually tuned according to the position of the illusion. The result of the mapping methods comparison pilot test showed that Power law-based mapping has high potential for funneling illusion performance compared to Linear, Logarithmic, and Square mappings. Likewise, existing funneling illusion research has mostly used Linear18,19,29, Logarithmic19,29, Square7,18,30 mappings, and mappings considering perceived intensity1,32.

Research objective

These perceptual tactile illusions are robust enough to render continuous and discrete sensations on body using tactor array systems27,28,30. Furthermore, the tactile funneling illusion can be applied to various research objectives depending on the modality, mapping method, body part, and other factors. Thus, experimental studies analyzing the perceptual characteristics of the tactile funneling illusion are required. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no studies compared the performance of funneling illusion mapping methods across different modalities on the trunk or shank. The performance of mapping methods can vary depending on experimental conditions (i.e., modality, actuator placement, experiment type, etc.) even for the same mapping method. Thus, this knowledge can contribute to developing diverse funneling illusion applications that can enhance navigation for the blind, sensory augmentation for assistance, VR, and mobile haptic interaction applications.

In this study, we evaluate the performance of the Linear, Logarithmic, Square, and Power law-based mappings, commonly used in most studies, across vibrotactile and electrotactile modalities using tactor array system applied to two body parts (i.e., trunk and shank). These body parts were selected frequently in previous studies for funneling illusion applications1,7,19. We hypothesize that the performance of funneling illusion mapping methods will vary depending on experimental conditions (i.e., modality, actuator placement, experiment). For instance, in the case of the electrotactile modality, Power law-based mapping is expected to be the most effective, as it considers individual perceived intensity, which rapidly varies with actuator intensity34.

Through this study, we provide guidelines for selecting appropriate funneling illusion mapping methods when using tactor array-based systems on the shank (4 CH) or trunk (6 CH). Consequently, better-performing funneling illusion cues can be provided by selecting a suitable mapping method and modality for each body part. The mapping methods and tactor array systems used in this study are detailed in the Methods Section. The experimental procedures performed with 20 healthy participants are presented in the Experiments Section. Experimental results and interpretations are presented in the Results and Discussion Sections, respectively. The conclusions from this study are presented in the Conclusion Section.

Methods

Funneling illusion generation

(a) Concept of funneling illusion and rule of determining \(\beta\). \(\phi _1\) and \(\phi _2\) is the actuator intensity of each CH1 and CH2. (b)-(c) Relationship between \(\beta\) and intensity of CH1 and CH2 with (b) vibrotactile and (c) electrotactile modality for a representative participant. Since both actuators’ perceived intensities at the reference intensities (\(\psi _{\textit{REF}_1}\) and \(\psi _{\textit{REF}_2}\)) are set to be the same for each modality, the actuator intensities at the reference intensities (\(\phi _{\textit{REF}_1}\) and \(\phi _{\textit{REF}_2}\)) may differ. (Dotted line: CH1, Solid line: CH2).

Fig. 1a indicates how the tactile system generates a funneling illusion. The desired direction between two actuators is denoted by \(\beta\), calculated using the equation \(\beta\) = \({x}/{y}\) (\(0 \le \beta \le 1\)) while \({x}\) is the position of the funneling illusion and \({y}\) is the distance between adjacent actuators from the funneling illusion point. Accordingly, \(\beta\) can be derived from the funneling illusion position relative to the adjacent actuator distance. To generate a funneling illusion, two actuators adjacent to the desired direction are used, and the actuator intensity of each actuator, CH1 and CH2, is denoted by \(\phi _1\) and \(\phi _2\), respectively, representing the amplitude of vibrotactile or electrotactile modalities.

\(\phi _{\textit{REF}}\) is the reference intensity of each actuator required to used to compare the performance between funneling illusion mapping methods. When the desired direction aligns with the location of an actuator (\(\beta\) = 0 or 1), that single actuator is activated with an intensity of \(\phi _{\textit{REF}}\). In other words, the intensity of each activated actuator is adjusted within the range of 0 to \(\phi _{\textit{REF}}\) depending on the desired direction according to the funneling illusion mapping method.

We compared four funneling illusion mapping methods: Linear, Logarithmic, Square, and Power law-based. Equations 1 and 2 represent the Linear and Logarithmic mappings, respectively. These mapping methods were originally proposed by Alles at the onset of funneling illusion research and continue to serve as fundamental methods employed in recent studies29. The Linear mapping is a simple method that linearly modulates actuator intensity according to the desired location of the funneling illusion. In addition, the Logarithmic mapping is a method of logarithmic variation of stimulus amplitude according to the desired location of the funneling illusion. Equation 3 represents the Square mapping used in vibrotactile grid displays, which modulates the intensities of actuators according to the square root of the illusion position30.

The relationship between actuator intensity and perceived intensity is not proportional, and perceived intensity can vary across different body parts, even at the same actuator intensity, regardless of modality18,34. Equation 4 represents Steven’s power law, which describes the relationship between actuator intensity (\(\phi\)) and perceived intensity (\(\psi\)). Using this relationship, Yun et al. applied PI-Linear mapping, as shown in Equation 5. The PI-Linear mapping pre-acquires the k and a parameters of participants in 4 through psychophysical experiments, averages the pre-acquired k and a parameters across participants, and then adjusts \(\phi\) to linearly modulate the perceived intensity (\(\psi\)) according to the desired location of the funneling illusion32. Using 4 and 5, 6 can be derived by dividing both sides by k, and the square root of a can be applied as in 7. As a result, the actuator intensity command is determined as shown in 7. While the PI-Linear mapping maintains fixed values for a and \(\phi _{\textit{REF}}\) across participants, variations in these parameters can occur within the same body part particularly for electrotactile modality1. Therefore, we proposed Power law-based mapping that utilizes the measured a and \(\phi _{\textit{REF}}\) of each participant instead of relying on fixed values1. Fig. 1b and 1c illustrate the actuator intensity for both channels under each mapping method (Linear, Logarithmic, Square, and Power law-based) using experimental parameters \((\phi _{\textit{REF}}\), a) obtained from a representative participant from the Experiment section. As shown in Fig. 1b and 1c, in our experimental setup, to ensure that the perceived intensities at the reference intensities (\(\psi _{\textit{REF}_1}\) and \(\psi _{\textit{REF}_2}\)) for CH1 and CH2 are the same, the actuator intensities at the reference intensities (\(\phi _{\textit{REF}_1}\) and \(\phi _{\textit{REF}_2}\)) can vary.

Vibrotactile and electrotactile tactor array systems

The purpose of this study is to compare the performance of funneling illusion mapping methods (Linear, Logarithmic, Square, Power law-based) for both vibrotactile and electrotactile array systems, specifically focusing on the continuity and accuracy of the cue on the trunk and shank. As shown in Fig. 2a and 2b, four tactile actuators were applied to the shank1 and six actuators were applied to the trunk. A system capable of generating tactile stimulation was used for this purpose. As shown in Fig. 2c, we employed the system described in our previous study, known as the transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) feedback system and vibrotactile feedback system, with the exception that the vibrotactile actuators were replaced13. In the previous study, the bi-phasic square pulses were applied at a frequency of 100 Hz with a pulse width of 200µs for the electrotactile modality1,13. This type of TENS stimulation helps mitigate muscle fatigue and effectively stimulates proprioceptive afferents1,35. In this study, we adopted the same electrotactile parameters due to their relevance to rehabilitation applications. To generate electrotactile sensations, 5 cm \(\times\) 5 cm electrode pads were used. The stimulation amplitude was adjustable from 0 to 100 mA at a 500 ohm load, with a resolution of 300 steps13.

The eccentric rotating mass (ERM) vibration motors employed in our previous study have a maximum frequency of 13000 RPM13. When using ERM-based vibration actuators, amplitude and frequency are correlated and vary simultaneously36. Since the perceived intensity is influenced by the stimulus frequency34, it is necessary to maintain a fixed frequency when adjusting stimulus intensity for the funneling illusion, in order to compare it with the electrotactile modality. Therefore, the previously used ERM-based vibration motors were replaced with linear resonance actuators (LRA) to enable a comparison between the two modalities. The LRA is capable of varying amplitude independently of frequency, and it is widely utilized in the field of vibrotactile research due to its cost-effectiveness27,28,37,38.

LRAs (VLV122792J, Vybronics, China) with a resonance frequency of 125 Hz and a vibration force of 5.5 G were used. An LRA generates vibration through translational motion using a spring-and-magnet-based system, and it is driven either by pulse width modulation (PWM) or AC pulse input signals. The amplitude can be modulated by adjusting either the PWM duty or the amplitude of the AC pulse input signal, respectively. In addition, the output frequency of the LRA matches the input signal frequency, whether using PWM or AC36. Although LRAs can only generate vibration near their resonance frequency, for a fair comparison with electrotactile modality, we used LRAs to provide vibrotactile sensation with amplitude modulation at a fixed frequency of 100 Hz. Each LRA was driven using PWM duty modulation at 100 Hz frequency with the amplifier (UNL2803A, STMicroelectronics, Switzerland). Based on the technical specifications of the linear resonant actuator (LRA) used in our setup, the LRA achieves maximum amplitude at 50 % duty. Thus, PWM duty was adjusted between 0 and 50 % to modulate the intensity of the vibrotactile sensation. Each LRA was housed in a 3D-printed enclosure to make it wearable. Consequently, the entire 3D-printed structure vibrated along with the LRA.

Experiments

Participants

We conducted experiments to compare the performance of funneling illusion mapping methods for vibrotactile and electrotactile modalities on the trunk and shank, respectively. Twenty healthy participants were recruited for the study (10 males and 10 females, Age: 21.0±1.7 years, Height: 166.8±7.9 cm, Weight: 63.3±9.9 kg, Dominant side: Left 2 and Right 18, Round of Trunk: 76.8±9.0 cm, Round of Shank: 36.7±3.1 cm). The experiment was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology, Gwangju, South Korea (20230504-HR-71-07-04). None of the participants had any neurological disorders, and all reported no discomfort during the experiment. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to the experiment.

Protocol

The experiment consisted of two stages: the experimental setup process, which involved mounting the actuators and experimental parameter acquisition, and the main experiment process, which included circle tracking and directional accuracy experiments. Each participant experienced both modalities (vibrotactile and electrotactile) and body parts (trunk and shank) in a randomized order. After the circle tracking experiment, the directional accuracy experiment was conducted. To minimize fatigue and reduce sensory adaptation, we provided a 1-minute rest between trials, following the approach used in previous studies32. A 10-minute break was provided whenever the tested body part was changed, and the device remained in place until the break. The order of the mapping methods evaluated in each experiment was also randomized. Vibrotactile and electrotactile modalities were tested on separate days, with an interval of at least 24 hours. The overall experimental process required 3 hours, with each modality taking 1.5 hours. Specifically, on average, the experimental procedure required 15 minutes to don the device and explain the protocol, 15 minutes for calibration of experimental parameters, and 50 to 60 minutes to complete the main experiments. Each participant received USD 40 as compensation for their participation.

Experimental setup

Concept diagram of the method of limits to equalizing the perceived intensity to the standard. The average value of the upper and lower limen is used. In this case, the perceived intensity of the yellow actuator is equalized to the blue actuator’s perceived intensity when the intensity is \(\phi _{Standard}\).

Fig. 2a presents the placement of all actuators. For the shank, actuators were mounted on the non-dominant side, with the first actuator located approximately 10 cm below the patella near the tibialis anterior muscle, and it was set as the front direction. The remaining three actuators were placed at 90-degree intervals around the gastrocnemius muscles of the participant in the backward, left, and right directions, resulting in a total of four actuators. For the trunk, actuators were mounted at a height of 2 cm above the navel. Six actuators were placed at 60-degree intervals around the participant’s external abdominal oblique, erector spinae, and rectus abdominis muscles. Likewise, to facilitate performance comparison, actuators were placed at a constant distance in a circular array configuration on both trunk and shank of each participant. The tactile array systems were positioned identically for each participant throughout the experiment.

Experimental parameter acquisition: \(\phi _{ref}\) and a

The experimental parameters for each actuator shown in 1-3 and 7 should be determined: \(\phi _{\textit{REF}}\) and a. We employed the method of limits, a widely used method for quantifying sensory sensitivity or thresholds34. This method was utilized to equalize the perceived intensity among actuators within the same modality and body part, or to measure the sensory or pain thresholds of the actuators. When the intensity of the standard actuator is applied equally to actuators at different locations, the perceived intensity can be different. In other words, this procedure was performed to ensure that the perceived intensity of the other actuators matched that of the standard actuator when tactors were applied to multiple locations. Accordingly, the intensity of the actuators at other locations was increased/decreased from a sufficiently low/high intensity relative to \(\phi _{Standard}\) so that their perceived intensities are the same as the perceived intensity at the \(\phi _{Standard}\) of the reference actuator. We confirmed that a 20 % lower/higher intensity of \(\phi _{\textit{Standard}}\) makes a noticeable difference in perceived intensity when stimulation is applied to different locations through trial and error. Fig. 3 shows the case when the perceived intensity at \(\phi _{\textit{Standard}}\) is used as the standard. \(\phi _{\textit{U}}\) or \(\phi _{\textit{L}}\) refers to the current intensity of the actuator that should be adjusted to match the perceived intensity of the standard. After confirming the standard intensity of the participant, the intensity of \(\phi _{\textit{U}}\)/\(\phi _{\textit{L}}\) was decreased/increased until the perceived intensity matched the standard, and its intensity was taken as the lower/upper limen. Subsequently, 20 % lower/higher intensity was set as \(\phi _{\textit{U}}\)/\(\phi _{\textit{L}}\), and the same process was conducted to acquire the upper/lower limen. For example, when \(\phi _{REF_1}\) of the Actuator 1 is set as \(\phi _{Standard}\), in order to determine \(\phi _{REF_2}\) of the Actuator 2, \(\phi _{UL_2}\)/\(\phi _{LL_2}\) need to be determined by starting Actuator 2 at an intensity 20 % lower/higher than \(\phi _{REF_1}\) and increasing/decreasing the intensity. The average of lower and upper limen (\(\phi _{\textit{UL}}\) and \(\phi _{\textit{LL}}\)) was used as the result according to the method of limits.

In the case of electrotactile feedback on the shank, we conducted the same process to acquire \(\phi _{\textit{REF}}\) as presented in our previous study1. The motor threshold for each actuator was measured by gradually increasing the current from 0 mA until a visible muscle contraction was observed. The motor threshold is defined as the minimum current intensity that induces a visible muscle contraction response39. Since muscle fatigue can be induced by intensity above the motor threshold, we used intensity below the motor threshold39. The motor threshold was denoted as \(\phi _{\textit{U}_\textit{i}}\), where i indicates the channel from 1 to 4. Since each motor threshold produces a different perceived intensity, we set the perceived intensity of each actuator to that of the actuator with the lowest perceived intensity, using the method of limits, as shown in Fig. 2a. In other words, the actuator with the lowest perceived intensity at its motor threshold was set as \(\phi _{\textit{Standard}}\). Then, the perceived intensities of the remaining actuators were adjusted to match that of the standard actuator through methods of limits. Through this process, \(\phi _{\textit{REF}_\textit{i}}\) with i ranging from 1 to 4 on the shank was determined.

However, in the case of electrotactile feedback on the trunk, determining the motor threshold is challenging due to the abdominal fat layer. Hence, we referred to a study40 that investigated the relationship between motor and pain thresholds in electrical stimulation. We initially determined the perceived intensity at which the stimulation became painful by gradually increasing the current, and it was used as the standard in the method of limits. After acquiring the pain thresholds, 65 % of the pain threshold was set as the motor threshold. The subsequent process for determining \(\phi _{\textit{REF}_\textit{i}}\) using the motor threshold followed the same procedure as that used for the shank, while i ranging from 1 to 640.

In a previous study comparing directional cue accuracy of the vibrotactile and electrotactile modalities using a tactor array, the electrotactile intensity was individually tuned for each participant, while the vibrotactile modality was set to its maximum intensity11. Accordingly, for the vibrotactile modality, the maximum actuator intensity, i.e., PWM duty 50 %, was set as \(\phi _{U_i}\), corresponding to the motor threshold in the electrotactile case. The remaining process for acquiring \(\phi _{\textit{REF}_\textit{i}}\) parameters was the same as that used for the electrotactile modality on both body parts. In conclusion, we obtained the \(\phi _{\textit{REF}_\textit{i}}\) parameter for each actuator in both modalities, which is necessary for generating the funneling illusion.

To determine \(a_\textit{i}\) in 7, we utilized the method of adjustment, which is a widely used method as the method of limits for quantifying sensory thresholds or sensitivity34. In the method of adjustment, the participant directly adjusts and compares the stimulation intensities to determine the desired parameter. First of all, we determined the sensory threshold of each actuator using the method of limit34. The point where stimulation became perceptible was established as the standard, and 0 intensity was defined as \(\phi _{\textit{L}_\textit{i}}\). To acquire \(a_\textit{i}\), the intensity range between the sensory threshold and \(\phi _{\textit{REF}}\) for the i-th actuator was divided into 30 steps. As shown in Fig. 4a, a graphical user interface (GUI) provided Intensity 1, Intensity 2, Increase and Decrease buttons. Pressing the Intensity 1 or Intensity 2 buttons transmitted the corresponding actuator intensity. Participants could compare intensities by pressing these buttons. Intensity 1 was initially set to the sensory threshold, and participants could adjust the intensity of Intensity 2 using the Increase/Decrease buttons. 1 step of 30 steps increased/decreased by pressing Increase/Decrease buttons. When the perceived intensity of Intensity 2 was twice that of Intensity 1, the participant pressed the Record button shown in Fig. 4a, which records the intensity of Intensity 2 value. Simultaneously, the perceived intensity (\(\psi\)) was also recorded as a power of 2, starting from 1 (sensory threshold). After each recording, the intensity of Intensity 1 was updated to the previous Intensity 2, and the adjustment process was repeated until Intensity 2 reached the maximum step of 30. Likewise, to reduce potential errors from the user judgment, we utilized the standardized psychophysical approach (method of adjustment), and the measuring process was repeated until the actuator intensity reach \(\phi _{ref}\). As shown in 4, the perceived intensity and actuator intensity have a linear relationship on a logarithmic scale. Therefore, \(a_\textit{i}\) was acquired using the least square method, a linear approximation method, based on the log values of each actuator intensity and their corresponding perceived intensity34. This process was performed for each actuator. In conclusion, we obtained \(a_\textit{i}\) for each actuator which is necessary for 7. However, the \(a_i\) may have error, as the method essentially requires a subjective response from the participant. Hence, the performance of the Power law-based mapping may have a potential possibility of large deviation.

Experimental procedure: Circle tracking & directional accuracy experiments

In the main experiment, our research objective was to compare the performance of the directional cues generated by the circular tactor array. Cue performance indicates continuity and accuracy for the continuous cue and accuracy for the discrete cue. Continuity refers to a cue that maintains a constant perceived intensity without disconnection, while accuracy refers to the degree to which the perceived direction of the cue matches the direction provided by the system. Thus, we conducted the circle tracking and directional accuracy experiments for each modality and body part. In each experiment, participants were requested to mark their perceived direction (angular position) of tactile stimulation around the entire perimeter on the guide circle displayed on the touchscreen GUI, as shown in Fig. 4b. Fig. 4c, which presents a conceptual diagram of the experiments. The blue line or dot indicates the participant’s response, the red dot represents the actual direction currently generated by the device, and the green line or dot indicates the stimulus direction given during the experiment. As shown in Fig. 4c, in the circle tracking experiment, tactile stimulation began in the front direction of the participant and moved continuously in a 360 degrees at a speed of 15 degrees/s using the tactor array system1. This slower speed, compared to previous studies, was due to the wider actuator displacement we applied15,18,19. In the circle tracking experiment, under ideal conditions, the participant would perceive a seamless circular motion and mark a complete circle. Since continuity indicates stimulation with a constant perceived intensity without disconnection, if the participant failed to perceive the stimulation at certain points (i.e., the sensation disappeared or dropped significantly in intensity compared to the starting point), they were instructed to pause marking and resume only when the perceived intensity returned to a level matching the initial reference. The experiment was conducted once in both clockwise and counterclockwise directions, with the initial direction order randomly assigned.

As shown in Fig. 4c, in the directional accuracy experiment, three intermediate points were added at equal intervals between the two actuators, resulting in a total of 16 points for the shank and 24 points for the trunk. Each experimental set consisted of two complete cycles, with the order of all 16 or 24 points was randomized continuously. For each mapping method, the directional accuracy experiment was conducted once. Each directional cue was presented as a single-shot stimulation with 2 seconds on and 3 seconds off, totaling 5 seconds per cue. After this interval, the next cue was given following the same on/off pattern. For the shank, this procedure was repeated 32 times, resulting in a total experimental duration of 160 seconds per trial. Similarly, for the trunk, 48 cues were presented, totaling 240 seconds per trial. Participants were instructed to mark the perceived direction of the stimulus on the guidance circle. Also, all participants successfully responded within 5 seconds. For adaptation to the experimental protocol, a familiarization session was conducted 1-2 times for each circle tracking and directional accuracy experiment using a randomly selected mapping method. In the familiarization session for the circle tracking experiment, participants became familiar with the cue speed (15 deg/s),which was also provided with the visual display. As shown in Fig. 2c, during the familiarization session, the current direction of stimulation was indicated by a red dial on a circular interface marked with angular values from 0 to 360 degrees. All participants reported that they clearly understood the cue speed during the familiarization session.

Data analysis

As shown in Fig. 4c, in the circle tracking experiment, the tracking completion rate and tracking error were measured to assess cue continuity and accuracy, respectively. The tracking completion rate is defined as the ratio of the marked portion to the guidance circle. Tracking error is defined as the root mean square (RMS) of the angular error between the marked direction and the direction provided by the system. Similarly, the directional error, which is the angular difference between the correct direction and the participant’s marked direction, was measured in the directional accuracy experiment. Additionally, in the directional accuracy experiment, participants were instructed not to respond if they could not perceive stimulation, and, in such cases, the error was recorded as 180 degrees. For both experiments, participants’ responses were projected onto the unit circle for data analysis1. A two-way repeated measure analysis of variance (RMANOVA) was employed to investigate differences due to Modality (Vibrotactile, Electrotactile) and Mapping methods (Linear, Logarithmic, Square, and Power law-based) in each experiment. The Q-Q plot evaluation tool was used to check the distribution of data, which was found to be within the acceptable range of normal distribution. Greenhouse-Geisser corrections (for \(\varepsilon\)<.75) were applied when Mauchly’s test of sphericity was violated (p<.05) and Bonferroni corrections were used for conducting post-hoc tests. Partial eta squared (\(\eta _{p}^{2}\)) was calculated to measure the effect size for two-way RMANOVA. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS V20.0 (IBM Corp., USA).

Results

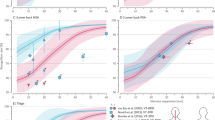

The experimental parameters from the experimental setup process are shown in Table. 1. The average round of body parts and actuator width are shown in Table. 2. Fig. 5 shows the response trace of the circle tracking experiment with the tracking completion rate and tracking error of a representative participant. From Fig. 5, Linear mapping for the vibrotactile modality and Power law-based mapping for the electrotactile modality provided continuous and accurate performance for continuous cues.

The bar plot with mean, standard deviation, and two-way RMANOVA results for the (a)-(h): circle tracking experiment, (i)-(l): directional accuracy experiment. (a)-(b): Trunk, Tracking Error, (c)-(d): Shank, Tracking Error, (e)-(f): Trunk, Tracking Completion Rate, (g)-(h): Shank, Tracking Completion Rate, (i)-(j): Trunk, Directional Error, (k)-(l): Shank, Directional Error. Statistically significant differences are marked based on the Post-hoc pairwise comparisons (*: p<.05, **: p<.01, ***: p<.001). The colored bars show the mean and the error bars show the standard deviation.

The results of the post-hoc tests are presented in Fig. 6. Simple main effects were tested for post-hoc analysis due to the significant interaction between modality and mapping methods in the results of each experiment. Fig. 6 shows tracking error (6a-6d) and tracking completion rate (6e-6h) from the circle tracking experiment. In addition, the results of the trunk are shown in Fig. 6a-6b and 6e-6f, while Fig. 6c-6d and 6g-6h show the results of the shank.

As shown in Fig. 6a, the tracking error of Linear (LIN) and Logarithmic (LOG) mappings under vibrotactile modality (VM) is significantly lower than Square (SQU) and Power law-based (POW) (LIN vs SQU: p<.001, LIN vs POW: p<.001, LOG vs SQU: p<.001, LOG vs POW: p<.001). However, the tracking error of POW and SQU mapping under electrotactile modality (EM) was significantly lower than that of LIN (SQU vs LIN: p<.01, POW vs LIN: p<.05). Furthermore, the tracking error of SQU under EM was significantly lower than that of Logarithmic (LOG) (SQU vs LOG: p<.05). As shown in Fig. 6b, there were significant differences between modalities on the LIN and LOG under the tracking error, respectively (VM vs EM on LIN: p<.05, VM vs EM on LOG: p<.05). In addition, there were significant differences between modalities on the SQU and POW under the tracking error, respectively (VM vs EM on SQU: p<.001, VM vs EM on POW: p<.05). As shown in Fig. 6e, tracking completion rate of Linear (LIN) mapping under vibrotactile modality (VM) is significantly higher than Square (SQU) and Power law-based (POW) (LIN vs SQU: p<.001, LIN vs POW: p<.05). However, the tracking completion rate of POW and SQU modality under electrotactile modality (EM) was significantly higher than that of LIN (SQU vs LIN: p<.001, POW vs LIN: p<.01). In addition, the tracking completion rate of SQU under EM was significantly higher than that of Logarithmic (LOG) (SQU vs LOG: p<.001). As shown in Fig. 6f, there were significant differences between modalities on the LIN and LOG under the tracking completion rate, respectively (VM vs EM on LIN: p<.001, VM vs EM on LOG: p<.01). From the circle tracking experimental results, LIN for vibrotactile and SQU & POW for electrotactile showed the best performance in cue continuity and accuracy during providing continuous cues on the trunk.

As shown in Fig. 6c, the tracking error of LIN under VM is significantly lower than SQU and POW (LIN vs SQU: p<.001, LIN vs POW: p<.01). The tracking error of LOG under VM is significantly lower than SQU (LOG vs SQU: p<.01). However, the tracking error of POW mapping under EM was significantly lower than that of LIN, LOG, and SQU (POW vs LIN, POW vs LOG, POW vs SQU: p<.05). As shown in Fig. 6d, there were significant differences between modalities on the POW under the tracking error (VM vs EM on POW: p<.01). The tracking completion rate of the LIN under VM is significantly higher than the LOG and POW (LIN vs LOG: p<.05, LIN vs POW: p<.05). However, the tracking completion rate of POW under EM was significantly higher than that of the other modalities (POW vs LIN: p<.001, POW vs LOG: p<.001, POW vs SQU: p<.001). The tracking completion rate of SQU under EM was significantly higher than that of LIN and LOG (SQU vs LIN: p<.001, SQU vs LOG: p<.01). In addition, as shown in Fig. 6h, there were significant differences between modalities on the LIN and LOG under the shank tracking completion rate, respectively (VM vs EM on LIN: p<.001, VM vs EM on LOG: p<.01). From the circle tracking experimental results, LIN and POW for vibrotactile and electrotactile, respectively provided the most continuous and accurate cues during continuous cue provision on the shank.

As shown in Fig. 6i, there is no significant difference between the mapping methods under both modalities on the trunk directional error. The directional error of VM under the LIN is significantly lower than the EM (VM vs EM: p<.05, See Fig. 6j). Therefore, the directional accuracy performance on the trunk for both modalities did not differ regardless of the mapping method.

The directional error of the POW and SQU under the EM is significantly lower than the LOG and LIN, respectively (POW vs LIN: p<.001, POW vs LOG: p<.01, SQU vs LIN: p<.01, SQU vs LOG: p<.01). In addition, except for the POW, there were significant differences between modalities on the LIN, LOG, and SQU under the shank directional error, respectively (VM vs EM on LIN and SQU: p<.001, VM vs EM on LOG: p<.05, See Fig. 6l). From the directional accuracy experimental results, no significant difference regarding the mapping method was observed for vibrotactile, however, POW for electrotactile provided the most accurate cue during providing discrete cues on the shank.

Discussion

In this study, we conducted a comparative analysis of 2-dimensional directional cues based on funneling illusion mapping methods (LIN, LOG, SQU, POW) and modalities (VM, EM) across both the trunk and shank. Furthermore, circle tracking and directional accuracy experiments were conducted to analyze cue continuity and accuracy for continuous cues and cue accuracy for discrete cues, respectively.

Seo et al. investigated the effects of amplitude and temporal factors on tracking error and continuity for vibrotactile moving sensation in handheld mobile devices28. They found a strong correlation between the amplitude variation rule and the movement distance of the sensation. This corresponds to the mapping methods and the results of the circle tracking experiment, respectively, in our experiment. For example, if the participant perceived that the change of direction was smaller than that provided by the system, it would be marked as an incorrect position in the circle tracking experiment. Since the tracking error is the difference between the participant’s response and the direction provided by the system, an incorrect response can increase the tracking error. In addition, the shorter the length of the perceived point marked continuously, the lower the tracking completion rate. The temporal factor was kept constant, and the performance was compared by changing the conditions for amplitude. As shown in Fig. 6, in the EM shank, POW, and EM trunk, SQU and POW showed the best performance for the circle tracking experiment. Furthermore, we confirmed that in VM, LIN provided the most continuous and accurate vibrotactile cue during the circle tracking experiment.

As shown in Fig. 6g, POW showed a significantly higher tracking completion rate for EM over the shank compared to other mapping methods. It supports the results of our previous pilot test on mapping method comparison through a circle tracking experiment with the shank1. Since the tracking completion rate was significantly higher in SQU than LIN and LOG, and POW did not show a significant difference from SQU, for the trunk in the tracking experiment, SQU and POW showed the best performance. Izumi et al. utilized EM on the shoulder to provide the sensory information of motion, position, and pressure of the fingers in a spinal cord injury patient. They reported that a speed of 7 cm/s was the most distinctly perceived over a 7 cm distance and SQU was more adequate than LIN with two electrode pairs18. Based on this study, Pfeifer et al. applied EM over the spina iliaca posterior superior for center of pressure feedback in a prosthetic limb. They reported that when the speed of the funneling illusion was 2 cm/s and 4 cm/s, it generated more distinguishable cues compared to 4 cm/s and 8 cm/s for 2 cm and 4 cm distances, respectively, with two electrode pairs. Furthermore, there was no clear difference between LIN and LOG19. We utilized 15 degrees/s, which corresponds to 3.20±0.37 cm/s for the trunk and 1.53±0.13 cm/s for the shank over distances of 12.81±1.50 cm, 9.18±0.77 cm, respectively. These speeds are relatively slow compared to previous studies. However, this slow speed was chosen because there is a proportional relationship between actuation duration and distance, which provides a clearer tactile apparent motion, and our inter-actuator distance is relatively large15. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the mapping method and spatiotemporal parameters tailored to the desired application to effectively transmit a clear tactile illusion. Based on our results, POW can be utilized for continuous feedback applications, such as navigation, with EM over the trunk (6 CH) and the shank (4 CH) at a cue speed of 15 degrees/s.

VM exhibited similar tracking completion rate trends for both body parts. As shown in Fig. 6e and 6g, the tracking completion rate of LIN was significantly higher than that of SQU and POW for both body parts. Additionally, Alles reported that LOG provided more uniform apparent loudness than LIN when applied to the upper arm with two vibrotactors spaced 5-inches distance29. Park et al. found no significant difference between LIN and LOG in transmitting 2D funneling illusions using a 7 \(\times\) 5 grid displacement of the tactor array and index and ring finger displacement for each hand with 4-tactors37. Also, Seo et al. suggested a polynomial equation combining intensity variation rules and funneling illusion speed for a mobile device utilizing two vibrotactors spaces 10 cm apart28. Accordingly, the performance of the funneling illusion mapping method of VM depends on the experimental conditions. In our study, LIN showed the best performance under our experimental conditions. Furthermore, during the experiment, stimulation was continuously delivered at 15 degrees/s, and overlap occurred as the stimulation intensity of one actuator increased while the other decreased (see Fig. 1b and 1c). Accordingly, we inferred that this overlap produced effects similar to tactile apparent motion. Zhao et al. reported that factors such as burst time, overlap duration, and onset function can impact the performance of the illusory stimulus. Furthermore, they found that the performance of the onset function varies depending on the experimental conditions for tactile apparent motion22. The onset function refers to a rising/falling waveform when the stimulus is turned on/off in tactile apparent motion. LIN and LOG, which involve more rapid intensity variations compared to other mapping methods, were more suitable under our experimental conditions, considering the speed of sensation, actuator distance, and related factors.

As depicted in Fig. 6f and 6h, the VM with LIN and LOG showed a significant difference compared to EM. The perceived intensity increase relative to the actuator intensity increase is generally more rapid in EM than in VM34. Therefore, EM mapping methods that do not consider perceived intensity may exhibit a notable performance difference with the funneling illusion mapping method compared to VM. Therefore, LIN is the best mapping method for providing continuous information, such as in a navigation application, when using VM over the trunk (6 CH) and shank (4 CH). Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 6b and 6d, the tracking error was smaller when using EM compared to VM, when applying high-performance mapping methods for each modality. Since the tracking error was calculated from the participant’s response, the tracking error would be lower when responses are made near the actuator attachment points. In addition, since EM induces a more localized sensation compared to VM, the tracking error of EM tends to be lower than that of VM11.

Liao et al. provided a vibrotactile funneling illusion to the ankle for blind navigation with 6 vibrotactors7. They conducted a directional accuracy experiment with 12 directions, evaluating one funneling illusion point per actuator interval, and the average directional error was 15.35 degrees. Our results from the directional accuracy experiment showed a different range of errors (Trunk, VM: 18.15±3.57 degrees, EM: 19.81±7.69 degrees, Shank, VM: 23.66±3.94 degrees, EM: 33.96±10.86 degrees) compared to theirs. Luo et al. evaluated the location accuracy of funneling illusion points with a haptic glove system that mounted actuators on the palm and fingertips. They reported that accuracy differences arose from the total number of evaluated positions, as increased cognitive load and specific points with higher accuracy33. We utilized four actuators and experimented with 16 directions, resulting in three funneling illusion points per actuator interval. Thus, this difference in the total number of evaluated points might contribute to the difference in error magnitude. Since high precision is required for navigation systems due to safety concerns, applying the proposed vibrotactors displacement to game or rehabilitation applications may be more appropriate than for navigation applications7.

As shown in Fig. 6k, when using the VM, there was no significant difference among mapping methods. Thus, any of the mapping methods evaluated in this study can be used when utilizing four vibrotactors on the shank. In addition, our prior observation suggests that the electrotactile cue is more accurate compared to the vibrotactile under muscular fatigue conditions, while there were no differences in the absence of muscular fatigue when using POW1. Since our current study did not involve muscle fatigue, there might be no significant difference in directional error between POW for VM and EM (See Fig. 6l). Therefore, further studies considering muscular fatigue as the experimental condition are needed to evaluate the potential for rehabilitation applications using EM.

As shown in Fig. 6j, there was no significant difference in directional error among the mapping methods at the trunk, regardless of the modality. Our previous study indicated that EM could replace the visual information as directional biofeedback rather than VM for trunk training with a trunk rehabilitation robot platform without the use of a funneling illusion13. Thus, when a funneling illusion is considered for such applications, the choice of mapping methods among those evaluated in the study becomes less critical. However, since the directional cue error of EM was significantly larger (p<.05, See Fig. 6j) under LIN, VM might be the preferable option when using LIN.

As we hypothesized, the performance of the funneling illusion mapping method depends on the modality, actuator placement, or the experiment. Based on the experimental results, our findings are as follows: Firstly, with our actuator displacement, Power law-based mapping with EM can provide the most continuous and accurate directional funneling illusion cue over the shank. Second, Square and Power law-based mappings with EM can provide continuous and accurate directional funneling illusion cues over the trunk during continuous cue provision. Third, Linear mapping delivers the most continuous and accurate directional funneling illusion cues with VM over both the trunk and shank during a continuous cue provision. Fourth, the choice of mapping method may not significantly affect the accuracy of directional funneling illusion cues when using VM over the shank and trunk, as well as EM over the trunk while providing a discrete cue. Based on our observations, we believe that funneling illusion mapping methods can be appropriately applied according to different applications and conditions.

Limitations and future works

Conditions beyond those we considered may affect the performance of the funneling illusion. Therefore, further in-depth studies focusing on other experimental conditions, such as speed of sensation, inter-actuator distance, number of evaluated directions, muscular fatigue, etc., are necessary to fully understand the mapping method selection based on the desired application. Furthermore, the experimental process should be refined, as it requires a long setup time of 30 minutes and may have potential errors from the human factors (ex. \(a_i\)). However, in our study, as shown in Fig. 6, the deviation of the Power law-based mapping was not large, which may be due to the adoption of a standardized method and repeated measurements to acquire \(a_i\)34. Moreover, since visual feedback can affect the performance of the tactile illusion, it may potentially influence experimental results due to the mismatch between the trunk shape and the circle in the GUI41. Thus, it is necessary to record responses with a GUI that more closely resembles the body part in further studies. In addition, to account for various applications, we will explore the dynamic experimental conditions, such as walking, running, arm swinging, etc., to identify the factors that improve the performance of the funneling illusion. Through this, the currently developed tactile systems can reduce the number of required actuators while achieving higher funneling illusion performance. For example, the number of actuators used in the sleeve-type tactile system42 can be reduced by improving funneling illusion performance through mapping method comparisons on the forearm. In addition, by tailoring experimental conditions to match the desired application, existing systems can be extended with improved funneling illusion performance. For instance, haptic feedback can be enhanced by simultaneously applying the tactile cues33 to a soft actuated glove system43,44, with improved funneling illusion performance through mapping method evaluations. Moreover, the comparison of funneling illusion mapping methods can be extended to planar-dimensional funneling illusions, which use planar-distributed actuator arrays33,45 or the body-penetrating funneling illusions, which are based on the actuators enclosing the body part46,47.

Conclusion

In this study, we compared the performance of the funneling illusion across different mapping methods (Linear, Logarithmic, Square, and Power law-based) and modalities (Vibrotactile, Electrotactile) over the trunk and shank. This evaluation was based on experiments conducted with 20 young healthy participants. The experimental results demonstrated that the performance of funneling illusion mapping methods varied depending on the modality, body part, and type of experiment. For the vibrotactile modality, Linear mapping was the most suitable for applications requiring continuous cue provision with our actuator configuration: trunk (6 CH) and shank (4 CH). For the electrotactile modality, the Power law-based mapping demonstrated superior performance on the shank for both continuous and discrete cues. In addition, both the Square and Power law-based mappings were more suitable for providing continuous cues over the trunk. However, several factors beyond those considered in this study, such as actuator spacing, cue speed, and experimental conditions, can influence the performance of the funneling illusion. Therefore, future studies should explore a broader range of variables and include other body parts, such as fingers, arms, etc., are needed to provide tactile cues with better performance for various applications. Nevertheless, this study offers valuable guidance for selecting appropriate mapping methods or modalities applicable to illusory sensory-based systems, such as navigation for the blind, sensory augmentation for assistance, VR, and mobile haptic interaction applications.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the main text.

References

Lee, J., Lee, H., Eizad, A. & Yoon, J. A tens based system for 2-dimensional balance biofeedback under muscle fatigue condition. IEEE Access 11, 5724–5736 (2023).

Afzal, M. R. et al. Effects of vibrotactile biofeedback coding schemes on gait symmetry training of individuals with stroke. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng.27, 1617–1625 (2019).

Trout, M. A., Harrison, A. T., Brinton, M. R. & George, J. A. A portable, programmable, multichannel stimulator with high compliance voltage for noninvasive neural stimulation of motor and sensory nerves in humans. Sci. Reports 13, 3469 (2023).

D’Alonzo, M., Dosen, S., Cipriani, C. & Farina, D. Hyve: hybrid vibro-electrotactile stimulation for sensory feedback and substitution in rehabilitation. IEEE Transactions on Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 22, 290–301 (2013).

Shull, P. B. & Damian, D. D. Haptic wearables as sensory replacement, sensory augmentation and trainer-A review. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil.12, 1–13 (2015).

Katzschmann, R. K., Araki, B. & Rus, D. Safe local navigation for visually impaired users with a time-of-flight and haptic feedback device. IEEE Transactions on Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 26, 583–593 (2018).

Liao, Z., Luces, J. V. S. & Hirata, Y. Human navigation using phantom tactile sensation based vibrotactile feedback. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett.5, 5732–5739 (2020).

Wall, C. III., Wrisley, D. M. & Statler, K. D. Vibrotactile tilt feedback improves dynamic gait index: a fall risk indicator in older adults. Gait & posture 30, 16–21 (2009).

Plaisier, M. A., Sap, L. I. & Kappers, A. M. Perception of vibrotactile distance on the back. Sci. Reports 10, 17876 (2020).

Han, J., Park, S., Jung, S., Choi, Y. & Song, H. Comparisons of changes in the two-point discrimination test following muscle fatigue in healthy adults. J. Phys. Ther. Sci.27, 551–554 (2015).

Stanke, D., Duente, T. & Rohs, M. Tactilewear: A comparison of electrotactile and vibrotactile feedback on the wrist and ring finger. In Proceedings of the 11th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Shaping Experiences, Shaping Society, 1–13 (2020).

Boljanić, T. et al. Psychometric evaluation of high-resolution electrotactile interface for conveying 3d spatial information. Sci. Rep.14, 19969 (2024).

Eizad, A., Lee, H., Lee, J. & Yoon, J. Evaluation of tens based biofeedback and warning for improvement of seated balance on a trunk rehabilitation robot. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett.7, 10818–10825 (2022).

Afzal, M. R. et al. Haptic based gait rehabilitation system for stroke patients. In 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 3198–3203 (IEEE, 2016).

Eid, M., Korres, G. & Jensen, C. B. F. Soa thresholds for the perception of discrete/continuous tactile stimulation. In 2015 Seventh International Workshop on Quality of Multimedia Experience (QoMEX), 1–6 (IEEE, 2015).

Kerdegari, H., Kim, Y. & Prescott, T. J. Head-mounted sensory augmentation device: Designing a tactile language. IEEE Trans. Haptics9, 376–386 (2016).

Lederman, S. J. & Jones, L. A. Tactile and haptic illusions. IEEE Trans. Haptics4, 273–294 (2011).

Izumi, T., Hoshimiya, N., Fujii, A. & Handa, Y. A presentation method of a traveling image for the sensory feedback for control of the paralyzed upper extremity. Syst. Comput. Jpn.19, 87–96 (1988).

Pfeifer, S., Çaldıran, O., Vallery, H., Riener, R. & Hernandez Arieta, A. Displaying centre of pressure location by electrotactile stimulation using phantom sensation. In 10th Vienna International Workshop on Functional Electrical Stimulation and 15th IFESS Annual Conference, 71–73 (University of Zurich, 2010).

Arieta, A. H., Afthinos, M. & Dermitzakis, K. Apparent moving sensation recognition in prosthetic applications. Procedia Comput. Sci.7, 133–135 (2011).

Shokur, S. et al. Assimilation of virtual legs and perception of floor texture by complete paraplegic patients receiving artificial tactile feedback. Scientific reports 6, 32293 (2016).

Zhao, S., Israr, A., Fenner, M. & Klatzky, R. L. Intermanual apparent tactile motion and its extension to 3D interactions. IEEE Trans. Haptics10, 555–566 (2017).

Lee, J., Kim, Y. & Kim, G. Funneling and saltation effects for tactile interaction with virtual objects. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 3141–3148 (2012).

Jun, Y.-J. & Choi, D.-S. Experimental setup for verifying the funneling illusion on the upper facial region. In 2024 IEEE 18th International Conference on Application of Information and Communication Technologies (AICT), 1–4 (IEEE, 2024).

Lin, Y. et al. Vibroarm: Enhancing the sensation of forearm deformation in virtual reality using vibrotactile funneling illusion. In 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR), 515–524 (IEEE, 2024).

Kim, Y., Lee, J. & Kim, G. J. Extending, “out of the body” tactile phantom sensations to 2d and applying it to mobile interaction. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput.19, 1295–1311 (2015).

Patel, P., Ray, R. K. & Manivannan, M. Power law based “out of body” tactile funneling for mobile haptics. IEEE Trans. Haptics12, 307–318 (2019).

Seo, J. & Choi, S. Perceptual analysis of vibrotactile flows on a mobile device. IEEE Trans. Haptics6, 522–527 (2013).

Alles, D. S. Information transmission by phantom sensations. IEEE transactions on man-machine systems 11, 85–91 (1970).

Israr, A. & Poupyrev, I. Tactile brush: drawing on skin with a tactile grid display. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2019–2028 (2011).

Schäfer, N., Seiler, J., Latsch, B., Kupnik, M. & Beckerle, P. Vibrotactile phantom sensations in haptic wrist rotation guidance. IEEE Trans. Hapticshttps://doi.org/10.1109/TOH.2025.3542604 (2025).

Yun, G., Oh, S. & Choi, S. Seamless phantom sensation moving across a wide range of body. In 2019 IEEE World Haptics Conference (WHC), 616–621 (IEEE, 2019).

Luo, H., Wang, Z., Wang, Z., Zhang, Y. & Wang, D. Perceptual localization performance of the whole hand vibrotactile funneling illusion. IEEE Transactions on Haptics (2023).

Gescheider, G. A. Psychophysics: the fundamentals (Psychology Press, 2013).

Dickstein, R., Laufer, Y. & Katz, M. Tens to the posterior aspect of the legs decreases postural sway during stance. Neurosci. Lett.393, 51–55 (2006).

Huang, H. et al. Experiment and investigation of two types of vibrotactile devices. In 2016 6th IEEE International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BioRob), 1266–1271 (Ieee, 2016).

Park, G. & Choi, S. Tactile information transmission by 2d stationary phantom sensations. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–12 (2018).

Quinn, R. et al. A shape-changing haptic navigation interface for vision impairment. Sci. Rep.14, 1–13 (2024).

Dosen, S. et al. Online tremor suppression using electromyography and low-level electrical stimulation. IEEE Transactions on Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 23, 385–395 (2014).

Ward, A. R. & Robertson, V. J. Sensory, motor, and pain thresholds for stimulation with medium frequency alternating current. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil.79, 273–278 (1998).

Remache-Vinueza, B., Guijarro-Molina, I. & Trujillo-León, A. Influence of duration and visual feedback on the perception of tactile illusions of motion. Sci. Rep.15, 10965 (2025).

Reed, C. M. et al. A phonemic-based tactile display for speech communication. IEEE transactions on haptics 12, 2–17 (2018).

Lai, J. et al. Design and evaluation of a bidirectional soft glove for hand rehabilitation-assistance tasks. IEEE Trans. Med. Robot. Bionics.https://doi.org/10.1109/TMRB.2023.3292414 (2023).

Lai, J. et al. A novel soft glove utilizing honeycomb pneumatic actuators (hpas) for assisting activities of daily living. IEEE Transactions on Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. (2023).

de Vlam, V., Wiertlewski, M. & Vardar, Y. Focused vibrotactile stimuli from a wearable sparse array of actuators. IEEE Trans. Haptics16, 511–517 (2023).

Kim, J., Oh, S., Park, C. & Choi, S. Body-penetrating tactile phantom sensations. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–13 (2020).

Lee, D., Oh, S., Choi, S. & You, B.-J. Vibrotactile metaphor of physical interaction using body-penetrating phantom sensations: Stepping on a virtual object. In 2021 IEEE World Haptics Conference (WHC), 367–372 (IEEE, 2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Translational Research Center for Rehabilitation Robots (NRCTR-EX23010), National Rehabilitation Center, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea, in part by GIST Research Institute(GRI) GIST-CNUH research collaboration grant funded by GIST in 2025, in part by Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) grant funded by the Korea government (MOTIE)(20241K00000010, Robot Utilization Production Support Center For SMR), and in part by the Glocal University 30 Project Fund of Gyeongsang National University in 2025.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L.: conceptualization, methodology, experiment, analysis, writing, and project administration, H.L.: conceptualization, methodology, analysis, writing, and supervision, M.K.: methodology and experiment, Y.K.: methodology, analysis, and supervision, J.Y.: supervision, review, and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J., Lee, H., Kim, M. et al. Comparative analysis of directional cue perception between vibrotactile and electrotactile using funneling illusion mapping methods. Sci Rep 15, 26280 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11436-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11436-6