Abstract

The increase in the incidence of zoonoses underlines the need for monitoring pathogens in wild animals. Recent studies have revealed the circulation of several microorganisms in rodents, in various geographic and environmental contexts, including African urban habitats. However, Mali, a landlocked country of West Africa, was not extensively studied for the circulation of the microorganisms in rodents. And this paucity of information puts the fight against rodent-borne zoonoses at a disadvantage. This is why we aimed through this study to improve knowledge of potentially zoonotic infectious agents carried by rodents in Mali (Bamako). Three hundred and seventy-one small mammal spleen samples taken from captures realized in 2021–2022 were analyzed by polymerase chain reaction. Eleven of them (i.e. 2.96%) were infected by microorganisms (Bartonella spp., Coxiella burnetii and Trypanosoma otospermophili). The most frequently detected microorganisms were Bartonella spp. (2.43%). We identified new genotypes of B. elizabethae (a species involved in some cases of infective endocarditis) and B. mastomydis. We also identified C. burnetii MS type 12, thus showing active circulation of a human-pathogenic genotype of Q fever agent in wild rodents. For the first time in Mali, Trypanosoma otospermophili was identified in a specimen of brown rat Rattus norvegicus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For several decades now, humanity faces an increase in the emergence of infectious diseases whose negative impact on public health, global economy, and society in general has been growing steadily1. Numerous cases of hospitalization and death have been recorded because of these diseases. Indeed, according to the WHO, 39 million people living with HIV were registered at the end of 2022 and 630,000 people died during the same year due to HIV2. More than six million deaths followed the emergence of COVID-19 up to 2023 (https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/deaths?m49=001&n=c). Dengue is showing a worrying trend of progression in Africa. In 2023, more than 270,000 cases were reported across 18 African countries, resulting in 753 deaths (https://www.afro.who.int/countries/burkina-faso/publication/dengue-who-african-region-situation-report-01-19-december-2023). In the same year, 25 countries reported outbreaks of other arboviral diseases such as yellow fever, chikungunya, Rift Valley fever, and West Nile virus, with a total of 19,569 confirmed cases and 820 deaths3.

Epidemics of Ebola, SARS, MERS, Zika, Lassa viruses, and many others have caused numerous deaths. They exemplify the ongoing emergence of large-scale, sometimes even pandemic, diseases and the significant threats they pose to public health. The world cannot remain indifferent to these threats; it is imperative to develop strategies to combat them. This begins with accurately identifying the reservoirs of microorganisms that cause infectious diseases4. Indeed, most of these microorganisms are known to have a zoonotic origin5, and non-human primates, bats and rodents have been identified as major reservoirs for most of the zoonotic microorganisms that have emerged in recent decades6.

Rodents are the world’s most abundant mammals. They account for nearly 40% of all mammals7. They play a major role in the emergence and re-emergence of many infectious diseases. Hundreds of infectious microorganisms, including viruses, bacteria, parasites and fungi, have been discovered in rodents8,9. Their close proximity to humans, especially in dwellings and agricultural sites, makes them important links in the transmission of zoonoses to humans. This is why an increase in the incidence of zoonoses underlines the crucial need for real-time monitoring of pathogens in wild animals such as rodents, particularly in high-risk regional “hot spots” where new emerging infectious diseases have been reported4,5.

In West Africa, in addition to the endemic Lassa hemorrhagic fever virus10,11, many rodent-borne zoonotic pathogens have been identified. Recent studies carried out in Gabon12 and Senegal13,14,15,16,17 have revealed the circulation of several microorganisms in rodents, including Bartonella spp., Borrelia spp., Coxiella burnetii, Anaplasma spp., Piroplasma spp., Hepatozoon spp., Trypanosoma spp., Leishmania spp., etc. In addition, data obtained from screening of rodent-hosted parasitic arthropods may be biased by the detection of microorganisms genetically close to pathogens but associated with arthropods only. Mali, a landlocked country which borders Senegal and where Lassa haemorrhagic fever is endemic in the southern region10, was not extensively studied for the circulation of microorganisms carried by rodents. Papers of Diarra et al.18 and Schwan et al.19 report different species of Bartonella detected in both small mammals and ectoparasites, whereas species of the Anaplasmataceae family and C. burnetii were detected exclusively in ectoparasites. A new genotype of the latter bacteria, causative agent of Q fever20 was recently identified in wild rodents from Northern Senegal, relatively close to Mali borders, suggesting developing enzootic outbreak there20.

Given the paucity of the information, the fight against zoonoses transmitted by rodents in Mali is disadvantaged. This is why we aimed through this study to improve knowledge of potentially zoonotic infectious agents carried by rodents in Mali, and more particularly in its capital, Bamako.

Results

Small mammal sampling

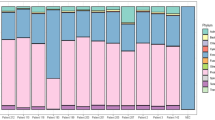

A selected set of three hundred and seventy-one (371) small mammals of six different species among the 1247 specimens that were captured in Bamako between October 2021 and October 2022 was subjected to analyses (S. Ag Atteynine et al., submitted). Four species (the house mouse Mus musculus, the brown rat Rattus norvegicus, the multimmmate mouse Mastomys natalensis, and the black rat Rattus rattus) are rodents of the family Muridae and one is from Nesomyidae (the giant rat Cricetomys gambianus). Shrews (Crocidura olivieri, Soricidae) were regularly captured at the same time with rodents.

Mus musculus, the most abundant species, represents 51.8% of the sample (192/371), followed by R. norvegicus (17.8%; 66/371), C. olivieri (11.6%; 43/371), M. natalensis (11.1%; 41/371), R. rattus (7.0%; 26/371) and C. gambianus (0.8%; 3/371). These proportions are similar to those observed in this small mammal community at the scale of the whole city. It is worth noting here that quantitatively, exotic invasive rodents (M. musculus and Rattus spp.) represent the majority (i.e. more the 75%) of the specimens in this sample, as well as in the urban community of small mammals of Bamako.

Molecular detection of microorganisms (Bacteria and Protozoa)

A total of 371 individual small mammal spleen samples were analysed in this study.

Eleven of them (i.e. 2.96%), all from rodents, were infected by microorganisms (Bartonella spp., C. burnetii and protozoa of the Kinetoplastida class). The most frequently detected microorganisms were Bartonella spp. (9/371; 2.43%). The frequency of detection of C. burnetii and Kinetoplastida was less than 1% (1/371 each) (Table 1).

Only one rodent of the species R. norvegicus showed a mixed infection with Bartonella spp. and Kinetoplastida. Bartonella spp. were mainly detected in R. norvegicus (6/66; 9.09%) but also in C. gambianus where 2 of the 3 individuals tested were found positive, and in C. olivieri (1/43; 2.33%). C. burnetii and Kinetoplastida were exclusively detected in R. rattus and R. norvegicus, respectively. The highest infection rate was observed in R. norvegicus where 7/66 (10.61%) of the individuals tested were found positive for microorganisms. Regarding Bartonella, PCRs targeting the ITS, rpoB and ftsZ genes provided nine, six and two informative partial sequences, respectively, at the end of the sequencing. The result of the BLAST analysis of the sequences of the ITS, rpoB and ftsZ genes allowed us to obtain a total of three groups of different sequences of these three genes. In view of the low inter-species similarity value of the rpoB gene compared to other genes (ITS, ftsZ) as described by La Scola (21), the rpoB gene sequences has been selected to identify the new genotypes (PP264222-PP264225 and PP264227). Indeed, three new genotypes of B. elizabethae (PP264223-PP264225), a known genotype of B. elizabethae (PP264226) and two new genotypes of B. mastomydis (PP264222 and PP264227) were found (Table 2).

The phylogenetic position of the Bartonella species identified by the rpoB gene in our study is presented in Fig. 1.

We were unable to amplify the rpoB and ftsZ genes on one spleen sample of the C. olivieri specimen previously tested positive for ITS. Furthermore, it should be noted that the sequencing of spleen samples of two R. norvegicus previously tested positive for ITS and rpoB has failed. Analyses of these three DNA sequences obtained with the 16–23 S intergenic spacer (ITS) revealed genotypes with homologies of 87.01%, 90.20% and 99.34% respectively with Bartonella florencae strain R4 from France 16–23 S ribosomal RNA intergenic spacer, partial sequence, Bartonella tribocorum main chromosome complete genome, strain BM1374166 and B. elizabethae strain NCTC12898 genome assembly, chromosome: 1, respectively. We failed to amplify the gltA gene in all nine samples previously tested positive for ITS.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of the rpoB gene portion of Bartonella genus bacteria showing the position of the identified Bartonella sequences obtained from different rodents. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together is shown next to the branches. GenBank accession numbers are provided. Scale bar indicates nucleotide sequence divergence.

C. burnetii DNA was detected in one black rat spleen sample by qPCR with primers and probes targeting IS1111 and IS30A spacers. To identify the genotype, we amplified six pairs of intergenic spacer primers, Cox2F/R, Cox5F/R, Cox18F/R, Cox56F/R, Cox57F/R, and Cox61F/R. Multispacer sequence typing (MST) genotyping of C. burnetii strains22 (https://ifr48.timone.univ-mrs.fr/mst/coxiella_burnetii/blast.html) using sequences from the amplification of these six primer pairs revealed C. burnetii MST group 12.

To identify the Kinetoplastida species found in one brown rat sample, we used a broad species PCR tool targeting the 28 S gene. This R. norvegicus DNA sample was successfully amplified and sequenced. The blast analysis of reverse strand of 392-bps-long portion were 100% identical to Trypanosoma otospermophili clone 14RD1608 large subunit ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence (MT271797.1). It should be noted that this same sample showed a B. elizabethae / T. otospermophili mixed infection.

Discussion

Through this study, we wanted to contribute to improving knowledge of blood-borne microorganisms circulation in small mammals in Mali, and more precisely in its capital city, Bamako. We recruited 371 rodents from which 371 spleen samples were taken. Of the seven pathogens tested, three (Bartonella spp., C. burnetii and Kinetoplastida sp.) were detected by qPCR. They were then amplified by conventional PCR and sequenced for identification. Less than 3% (11/371) of the small mammals analyzed were infected by at least one of the three microorganisms detected. This result is difficult to compare with the results of other studies in the region, given that several studies based on epidemiological investigation of communities of microorganisms (bacteria, parasites, viruses, etc.) circulating in small mammals have not mentioned overall infection rates. Examples include the studies carried out in Mali in 202018, in Senegal in 202014, and Tunisia in 202123. However, compared with one of the very few studies to have these data in the region, in Senegal in 202313, the infection rate obtained in our study is much lower. It is also much lower than the rate obtained in Germany in 201924. The difference in rates observed between this study and ours could be due to the fact that the rodent species included in this study were different from those in our study. We could speculate that the species included in our study, and especially M. musculus which dominates in our sample, would have a less diverse and smaller pool of microorganisms than the other species. However, due to lack of evidence through exhaustive studies, we cannot confirm this. Furthermore, this difference could be because most of the specimens of small mammals on which the microorganisms were detected in our study belong to exotic invasive species. As such, the latter would have a lower reserve of microorganisms than the native species living in Europe: They may have lost some of their native microorganisms during introduction / invasion processes, and at the same time the colonization of these species by microorganisms from the regions where they are introduced would not compensate for the loss of indigenous microorganisms25.

In this study, Bartonella spp. was the most frequently detected microorganism, with a prevalence rate of 2.43% (9/371). This prevalence is similar to the ones recorded in studies carried out in the Ferlo region of Senegal in 202014 and in 202313, and in Franceville, Gabon in 202112, where conventional PCR results suggested rates of 5.85% (10/171), 4% (5/125) and 2.53% (5/198), respectively. In contrast, our results differ from those obtained in Germany24, Germany and the Czech Republic26, which describe prevalence rates of 78.2% (129/165) and 67.3% (216/321), respectively. In view of the argument presented above, it would be logical that the prevalence of Bartonella among invasive exotic species in Africa is much lower than that described among native species in Europe. However, an exhaustive comparative study should be carried out in order to provide more information and confirm this observation.

Analysis of the six DNA sequences obtained with the rpoB genes revealed sequences closely related to either B. elizabethae or B. mastomydis. Three new B. elizabethae genotypes detected in three rodents (two R. norvegicus and one C. gambianus) each showed homologies of 99.47%, 99.14% and 96.13% with B. elizabethae strain NCTC12898 genome assembly. In a fourth rodent (R. norvegicus), the Bartonella sequence detected showed 100% homology with B. elizabethae strain THSKR-008. These results are supported by the fact that, like the identification of B. elizabethae as the cause of human endocarditis27, this species had previously been identified in small mammals27. It is a species that circulates in rodents, mostly in rats. Species similar to B. elizabethae also infect other genera of rats, shrews and gerbils28. B. elizabethae has a worldwide distribution, reflecting its close host–pathogen relationship with rats. As rats are invasive species found across the globe and tend to follow human populations, it is not surprising that associated Bartonella strains from different regions exhibit close genetic similarities. This appears to be the case for B. elizabethae and its rat hosts: as shown in the phylogenetic tree, the B. elizabethae strains identified in our study are genetically similar to strains from various parts of the world, including Asia, Europe, and the Americas.

B. elizabethae is a relatively rare species in humans but is considered potentially pathogenic. It has been isolated from a patient with infectious endocarditis, confirming its ability to cause cardiovascular infections29.

Two new genotypes of B. mastomydis with homologies of 99.41% and 96.87% with B. mastomydis strain 008 were detected in R. norvegicus and C. gambianus respectively. This result reveals the participation of R. norvegicus and C. gambianus in the circulation of new Bartonella genotypes. Indeed, the role of C. gambianus as a reservoir of Bartonella was recently mentioned in a study carried out in Dakar, Senegal in 202230 .

B. mastomydis has not been associated with any human cases to date. It was recently described in West Africa from the rodent Mastomys erythroleucus, and no link to human disease has been established31.

Analyses of three DNA sequences obtained with the 16–23 S intergenic spacer (ITS) revealed genotypes with homologies of 87.01%, 90.20% and 99.34% respectively with B. florencae strain R4 from shrew in France, B. tribocorum strain BM1374166 and B. elizabethae strain NCTC12898 respectively. It should be noted, however, that these results are not sufficient to identify these genotypes as new species in accordance with the criteria for describing new Bartonella species described by La Scola et al.21.

The detection of different types of Bartonella genotype in this study concur with the fact that species of the Bartonella genus are characterized by a diversity of genotypes carried by small mammals28,32.

In this study, we found only one rodent (R. rattus) out of 371 small mammals tested (0.27%) infected with C. burnetii. This result is similar to that of a study carried out in the Ferlo region of Senegal in 202014, which was unable to detect C. burnetii in the following species of the Muridae family: Arvicanthis niloticus, Gerbillus nigeriae, Taterillus sp., Mastomys erythroleucus, Mus musculus. The prevalence obtained in our study is also close to that obtained previously in Mali (prevalence rate 2.3%)18. Conversely, it should be noted that in 2023 in the Ferlo region in Senegal (neighboring of the Kayes region in Mali)20 a prevalence rate of 19.2% in a rodent community made up of the following species: A. niloticus, Desmodilliscus braueri, Gerbillus nancillus, G. nigeriae, Jaculus jaculus, Taterillus sp., and Xerus erythropus. All these rodents were infected by the same new genotype of C. burnetii. We did not identify this new genotype in small mammals from Bamako, the only genotype identified in R. rattus corresponding to the previously described genotype 12. Thus, we believe that the epizootic outbreak of C. burnetii infection in Ferlo, Senegal in 202320 is probably local and has not (yet? ) extended in Mali. Such discordance in prevalence corresponds to previous observations that C. burnetii infection rates in domestic and wild animals vary from place to place33.

It should be noted that genotype 12 of C. burnetii had previously been detected in Algeria in cow’s milk34,35 and in Italy in cheese produced from ewe’s, goat’s and bovine milk35,36,37. It had also been identified in human clinical samples (in Switzerland, France and Senegal)34,35,37,38. However, to our knowledge, this is the first time that the MST12 genotype has been identified in rodents.

Since the beginning of studies on Q fever, various rodent models have proved highly susceptible to infection39. Despite this fact, wild rodents have not often been considered important reservoirs of Q fever. Several studies suggest, however, that rodents are potential sources of human infection such as capybaras in French Guiana40. In Egypt, rats seem to be an important excreting reservoir of Q fever harboring C. burnetii genotypes almost identical to those isolated from humans41. This would not exclude the hypothesis that the R. rattus tested positive for C. burnetii MST12 in our study could be a reservoir of human Q fever in Mali.

Here, T. otospermophili was also identified in a rodent of the species R. norvegicus. In fact, T. otospermohili is a species of the Trypanosoma genus42. This result matches those of a study carried out in Gabon12, that identified T. otospermophili in R. rattus. In Mali, Trypanosoma lewisi was detected in R. rattus as well as in Mastomys natalensis43, . Our study has the merit of having identified T. otospermophili in a rodent in Mali for the first time. This microorganism also parasitizes ground squirrels (Spermophilus spp.) in North America, Europe and Asia44. To date, no evidence of its pathogenicity in humans has been demonstrated.

In conclusion, identification of a MS type 12 of C. burnetii in R. rattus is an important finding showing active circulation of human-pathogenic genotype of Q fever agent in wild rodents. Permanent presence of Q fever reservoir in such a big city as Bamako may present an important sanitary threat. Therefore, monitoring should be organized to determine whether this genotype is circulating in Bamako.

We identified new genotypes of B. elizabethae and B. mastomydis in rodents. It is important to note that in the absence of clear evidence, we cannot say whether these new genotypes detected in rodents in Bamako are pathogenic for humans. However, in view of the role of B. elizabethae in the occurrence of certain cases of infective endocarditis in humans45,27, epidemiological surveillance of this bacterium is important.

We also note that for the first time in Mali, T. otospermophili was identified in a specimen of brown rat R. norvegicus. T. otospermophili is neither common nor currently recognized as pathogenic in humans. To date, no human infections have been documented in the scientific literature, and its role in human and animal pathology remains to be elucidated.

Understanding some limitations of the present study we encourage performing a large-scale continuous screening of rodents in African cities in order to clarify their potential roles as reservoir of emerging human infections. Interactions between exotic invasive and native species should also be followed, to check for their potential effects on zoonotic agents exchange and circulation.

Materials and methods

Study area and samples collection

The “Small mammals of Bamako: inventory, distribution determinants, hosted parasites” project (including the trapping of small mammals, their sacrifice and autopsy for biological samples intended for any genetic or epidemiological study) was approved by the ethics committee of the National Institute of Public Health of Mali (decision no. 18/2021 / CE-INSP). It also received prior informed consent, in accordance with the provisions of the Nagoya protocol signed by Mali, from the National Director of Water and Forests of Mali (letter 0976/MEADD-DNEF of November 25, 2021).

The study area corresponds to the district of Bamako in southwest Mali. The samples analysed here were taken from captures realized between October 2021 and October 2022 in various quarters of the six communes of the city. Elements of the trapping procedures followed here have already been described elsewhere46. Twelve quarters were sampled as representative of the cityscape diversity in terms of urbanization and socio-economic characteristics, without being too close from each other in order to ensure good spatial coverage of the city (Fig. 2). Captured small mammals were identified following keys provided in Granjon & Duplantier (2009)47, euthanized by cervical dislocation and handled in accordance with the relevant requirements of Malian legislation and the live animal capture guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists48. Body measurements were taken before autopsy and reproductive status was noted. Tissues, including spleen, were preserved in 95% ethanol for further analyses. We chose to use spleen samples because the spleen of small mammals, particularly rodents, is a key organ for detecting zoonotic pathogens, due to its central role in immune function and its capacity to accumulate blood-borne microorganisms. Its accessibility and usefulness in large-scale field studies make it a valuable tool for epidemiological surveillance and understanding host-pathogen dynamics.

Molecular detection

DNA extraction

For each spleen, a small piece (10 mg) was crushed and incubated for at least four hours with proteinase K. DNA extraction was performed using NucleoMag Tissue kit for DNA purification from cells and tissue (Macherey-Nagel, France), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA extracts were then stored at -20 °C until PCR analysis.

PCR amplification

Seven groups of blood-borne pathogens, most of them zoonotic, have been screened: Bartonella spp., C. burnetii, Borrelia spp., Anaplasmataceae spp., Piroplasma spp., Hepatozoon spp., and Kinetoplastida.

The initial screening of samples was performed using qPCR systems with wide specificity (genus or family-specific) (Table 3). For Real-Time PCR, the reaction mix contained 5 µL of the DNA template, 10 µL of the Roche master mix (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany), 0.5 µL (20 µM) of each reverse and forward primers, 0.5 µL (5 µM) of the FAM-labeled probe), 0.5 µL of uracil DNA glycosylase (UDG), and 3 µL of distilled water DNAse and RNAse free, for a final volume of 20 µL. The real-time qPCR amplification was carried out in a CFX96 Real-Time system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Foster City, CA, USA) using the following thermal profile: incubation at 50 °C for two minutes for UDG action (eliminating PCR amplicons’ contaminant), then an activation step at 95 °C for three minutes followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s and an annealing-extension at 60 °C for 30 s. With the exception of C. burnetii for which confirmation of a positive sample was obtained after two qPCRs (IS1111 and IS30A), for all systems, any sample presenting a cycle threshold (Ct) value less than or equal to 33 Ct was analyzed by conventional PCR for confirmation of positivity.

Amplification of these samples by conventional PCR was carried out using an automated DNA thermal cycler (GeneAmp PCR Systems Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France). PCR reactions contained 5 µL of the DNA template, 12.5 µL of Ampli Taq Gold master mix, 0.75 µL of each primer (20 µM) and 6 µL of distilled water DNAse and RNAse free. The conditions for conventional PCR were as follows: one incubation step at 95 °C for 15 min, 35 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s annealing at a different hybridization temperature for each PCR assay, and one minute at 72 °C, followed by a final extension for five minutes at 72 °C (Table 3). Negative and positive controls were included in each molecular assay. The success of amplification was confirmed by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel. We considered positive PCR product when the specific DNA band of interest was observed in the transilluminator. The positive PCR product was purified using NucleoFast 96 PCR plates (Macherey–Nagel, Hoerdt, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

We selected two genetic markers for improved characterization of Bartonella spp. identified by qPCR: the rpoB gene and the ITS region, both of which are routinely used for Bartonella identification and characterization21,60.

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

The amplicons were sequenced using the Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Perkin Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with an ABI automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems). The obtained sequences were assembled and edited using ChromasPro software (ChromasPro 1.7.7, Technelysium Pty Ltd., Tewantin, Australia). Then, the sequences were compared with those available in the GenBank database by NCBI BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Evolutionary analyses were conducted using TOPALi version 2.5 (http://www.topali.org). The sequences of the rpoB genes amplified in this study with other Bartonella rpoB sequences available on GenBank (852 positions in the final dataset) were aligned using ClustalW (https://www.genome.jp/tools-bin/clustalw) implemented on BioEdit version 3 (https://bioedit.software.informer.com). The evolutionary history was inferred by using the maximum likelihood method based on the Hasegawa–Kishino–Yano model plus invariant sites plus gamma distribution.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the Genbank repository with following accession codes: PP264222, PP264223, PP264224, PP264225, PP264226, PP264227Links : https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PP264222.1?report=GenBank https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PP264223.1?report=GenBank https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PP264224.1?report=GenBank https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PP264225.1?report=GenBank https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PP264226.1?report=GenBank https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PP264227.1?report=GenBank. This study was conducted and reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) available at https://arriveguidelines.org, and in compliance with applicable ethical standards for research involving animals.

References

Morand, S. Emergence of infectious diseases. Risks and issues for societies. Editors: Serge Morand and Muriel Figuié. Versailles (FR): Éditions Quae 2018.

ONUSIDA. Fiche d’information 2023; Statistiques mondiales sur le VIH; Personnes vivant avec le VIH; Personnes vivant avec le VIH ayant accès à un traitement anti rétroviral; Nouvelles infections au VIH; Décès liés au sida; Populations clés Femmes et filles. 6, 1–3 (2023).

Bangoura, S. T. et al. Arbovirus epidemics as global health imperative, Africa, 2023. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 31 (2), 1–8 (2025).

Keita, M. B., Hamad, I. & Bittar, F. Looking in apes as a source of human pathogens. Microb. Pathog. 77, 149–154 (2014).

Jones, K. E. et al. Global trends in emerging infectectious diseases. Nature. 451 (7181), 990–994 (2008).

Albery, G. F. & Becker, D. J. Fast-lived hosts and zoonotic risk. Trends Parasitol. 37 (2), 117–129 (2021).

Burgin, C. J., Colella, J. P., Kahn, P. L. & Upham, N. S. How many species of mammals are there? J. Mammal. 99 (1), 1–14 (2018).

Issae, A., Chengula, A., Kicheleri, R., Kasanga, C. & Katakweba, A. Knowledge, attitude, and preventive practices toward rodent-borne diseases in Ngorongoro district, Tanzania. J. Public. Health Afr. 14 (6), 2385 (2023).

Meerburg, B. G., Singleton, G. R. & Kijlstra, A. Rodent-borne diseases and their risks for public health. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 35, 221–270 (2009).

Safronetz, D. et al. Geographic distribution and genetic characterization of Lassa virus in Sub-Saharan Mali. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7 (12), 4–12 (2013).

Kenmoe, S. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology of Lassa virus in humans, rodents and other mammals in Sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14 (8), 1–29 (2020).

Mangombi, J. B. et al. First investigation of pathogenic bacteria, protozoa and viruses in rodents and shrews in context of forest-savannah-urban areas interface in the City of Franceville (Gabon). PLoS One. 16 (3), 1–28 (2021).

Mangombi-Pambou, J. B. et al. Molecular survey of Rodent-Borne infectious agents in the Ferlo region, Senegal. Genes (Basel). 14 (5), 1107 (2023).

Dahmana, H. et al. Rodents as hosts of pathogens and related zoonotic disease risk. Pathogens. 9 (3), 202 (2020).

Diagne, C. et al. Ecological and sanitary impacts of bacterial communities associated to biological invasions in African commensal rodent communities. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 1–11 (2017).

Ouarti, B. et al. Pathogen detection in Ornithodoros sonrai ticks and invasive house mice Mus musculus domesticus in Senegal. Microorganisms. 10 (12), 2367 (2022).

Diatta, G. et al. Borrelia infection in small mammals in West Africa and its relationship with tick occurrence inside burrows. Acta Trop. 152, 131–140 (2015).

Diarra, A. Z. et al. Molecular detection of microorganisms associated with small mammals and their ectoparasites in Mali. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 103 (6), 2542–2551 (2020).

Schwan, T. G. et al. Endemic foci of the Tick-Borne relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia crocidurae in mali, West africa, and the potential for human infection. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6 (11), 1924 (2012).

Mangombi-Pambou, J. B. et al. New genotype of Coxiella burnetii causing epizootic Q Fever outbreak in rodents, Northern Senegal. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 29 (5), 1078-1081 (2023).

La Scola, B., Zeaiter, Z., Khamis, A. & Raoult, D. Gene-sequence-based criteria for species definition in bacteriology: the Bartonella paradigm. Trends Microbiol. 11 (7), 318–321 (2003).

Glazunova, O. et al. Coxiella burnetii genotyping. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11 (8), 1211–1217 (2005).

Selmi, R. et al. Zoonotic vector-borne bacteria in wild rodents and associated ectoparasites from Tunisia. Infect. Genet. Evol. 95:105039 (2021).

Galfsky, D., Król, N., Pfeffer, M. & Obiegala, A. Long-term trends of tick-borne pathogens in regard to small mammal and tick populations from Saxony, Germany. Parasit. Vectors. 12 (1), 1–14 (2019).

Torchin, M. E., Lafferty, K. D., Dobson, A. P., McKenzie, V. J. & Kuris, A. M. Introduced species and their missing parasites. Nature. 421 (6923), 628–630 (2003).

Obiegala, A. et al. Highly prevalent bartonellae and other vector-borne pathogens in small mammal species from the Czech Republic and Germany. Parasit. Vectors. 12 (1), 1–8 (2019).

Tay, S. T., Mokhtar, A. S., Zain, S. N. M. & Low, K. C. Isolation and molecular identification of bartonellae from wild rats (Rattus species) in Malaysia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 90 (6), 1039–1042 (2014).

Buffet, J. P., Kosoy, M. & Vayssier-Taussat, M. Natural history of Bartonella-infecting rodents in light of new knowledge on genomics, diversity and evolution. Future Microbiol. 8 (9), 1117–1128 (2013).

Daly, J. S. et al. Rochalimaea elizabethae sp. nov. isolated from a patient with endocarditis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31 (4), 872-881 (1993).

Demoncheaux, J. P. et al. Detection of potential zoonotic Bartonella species in African giant rats (Cricetomys gambianus) and fleas from an urban area in Senegal. Microorganisms. 10 (3), 489 (2022).

Dahmani, M. et al. Noncontiguous finished genome sequence and description of Bartonella mastomydis sp. nov. New Microbes New Infect. 25, 60–70 (2018).

Kraljik, J. et al. Genetic diversity of Bartonella genotypes found in the striped field mouse (Apodemus agrarius) in central Europe. Parasitology. 143 (11), 1437–1442 (2016).

Gong, X. Q. et al. Occurrence and genotyping of Coxiella burnetii in hedgehogs in China. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 20 (8), 580–585 (2020).

Menadi, S. E. et al. Serological, molecular prevalence and genotyping of Coxiella burnetii in dairy cattle herds in Northeastern Algeria. Vet. Sci. 9 (2), 40 (2022).

Mohabati Mobarez, A. et al. Genetic diversity of Coxiella burnetii in Iran by Multi-Spacer sequence typing. Pathogens. 11 (10), 1–12 (2022).

Galiero, A. et al. Occurrence of Coxiella burnetii in goat and Ewe unpasteurized cheeses: screening and genotyping. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 237, 47–54 (2016).

Di Domenico, M. et al. Genetic diversity of Coxiella burnetii in domestic ruminants in central Italy. BMC Vet. Res. 14 (1), 8–14 (2018).

Chochlakis, D. et al. Genotyping of Coxiella burnetii in sheep and goat abortion samples. BMC Microbiol. 18 (1), 1–9 (2018).

Davis, G. E. & Cox H. R. A filter-passing infectious agent isolated from ticks. Public Health Report. 53 (52), 2259-2282 (1938).

Christen, J. R. et al. Capybara and brush cutter involvement in Q fever outbreak in remote area of Amazon rain forest, French guiana, 2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 26 (5), 993–997 (2020).

Abdel-Moein, K. A. & Hamza, D. A. Rat as an overlooked reservoir for Coxiella burnetii: A public health implication. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 61, 30–33. (2018).

Hilton, D. F. J. & Mahrt, J. L. Taxonomy of trypanosomes (Protozoa: Trypanosomatidae) of Spermophilus spp. (Rodentia: Sciuridae). Parasitology. 65 (3), 403–425 (1972).

Schwan, T. G. et al. Fleas and trypanosomes of peridomestic small mammals in sub-Saharan Mali. Parasit. Vectors. 9 (1), 1–7 (2016).

Hilton, D. F. J. Prevalence of Trypanosoma otospermophili (protozoa: Trypanosomatidae) in five species of Spermophilus (Rodentia: Sciuridae). Parasitology. 65 (3), 427–432 (1972).

Mogollon-Pasapera, E., Otvos, L., Giordano, A. & Cassone, M. Bartonella: emerging pathogen or emerging awareness? Int. J. Infect. Dis. 13 (1), 3–8 (2009).

Granjon, L. et al. Commensal small mammal trapping data in Southern senegal, 2012–2015: where invasive species Meet native ones. Ecology. 102 (10), 23708 (2021).

Margareth, H. No Title طرق تدريس اللغة العربية. Экономика Региона. 32 p. (2017).

Sikes, R. S. & Gannon, W. L. Guidelines of the American society of mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research. J. Mammal. 92 (1), 235–253 (2011).

Mediannikov, O., Fenollar, F. Looking in ticks for human bacterial pathogens. Microb Pathog. 77, 142–148 (2014).

Jensen, W.A., Fall, M.Z., Rooney, J., Kordick, D.L., Breitschwerdt, E.B. Rapid identification and differentiation of Bartonella species using a single-step PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. 38(5), 1717–1722 (2000).

Renesto, P., Gouvernet, J., Drancourt, M., Roux, V., Raoult, D. Use of rpoB gene analysis for detection and identification of Bartonella species. J Clin Microbiol. 39(2), 430–437 (2001).

Birtles, R.J., Raoult, D. Comparison of partial citrate synthase gene (gltA) sequences for phylogenetic analysis of Bartonella species. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 46(4), 891–897 (1996).

Mediannikov, O., Fenollar, F., Socolovschi, C., Diatta, G., Bassene, H., Molez, J.F, et al. Coxiella burnetii in humans and ticks in rural Senegal. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 4(4), 1–8 (2010).

Glazunova, O., Roux, V., Freylikman, O., Sekeyova, Z., Fournous, G., Tyczka, J., et al. 2005 Glazunova Coxiella burnetii Genotyping. Emerg Infect Dis. 11(8), 1211–1217 (2005).

Mediannikov, O., Abdissa, A., Socolovschi, C., Diatta, G., Trape, J.F., Raoult, D. Detection of a new Borrelia species in ticks taken from cattle in southwest Ethiopia. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 13(4), 266–269 (2013).

Mangombi-Pambou, J.B., Granjon, L., Flirden, F., Kane, M., Niang, Y., Davoust, B., et al. Molecular Survey of Rodent-Borne Infectious Agents in the Ferlo Region, Senegal. Genes. 14(5), (2023).

Dahmana, H., Amanzougaghene, N., Davoust, B., Normand, T., Carette, O., Demoncheaux, J.P, et al. Great diversity of Piroplasmida in Equidae in Africa and Europe, including potential new species. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vprsr.2019.100332 (2019).

Medkour, H., Varloud, M., Davoust, B., Mediannikov, O. New molecular approach for the detection of kinetoplastida parasites of medical and veterinary interest. Microorganisms. 8(3), 1–17 (2020).

Hodžić, A., Alić, A., Prašović, S., Otranto, D., Baneth, G., Duscher, G.G. Hepatozoon silvestris sp. Nov.: Morphological and molecular characterization of a new species of Hepatozoon (Adeleorina: Hepatozoidae) from the European wild cat (Felis silvestris silvestris). Parasitology. 144(5), 650–661 (2017).

Rolain, J., Franc, M., Davoust, B. & Raoult, D. Molecular detection of Bartonella cat fleas, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9 (3), 338–342 (2003).

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to the inhabitants of the Bamako for participating in this study. They sincerely thank the IHU Fondation Méditerranée Infection for supporting this work and enabling the study to take place.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CK wrote the main manuscript. CK, LG and JM contributed to the drafting of the methodology. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumakamba, C., Granjon, L., Mangombi-Pambou, J. et al. Zoonotic microorganisms in native and exotic invasive urban small mammals of bamako, Mali. Sci Rep 15, 31204 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11443-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11443-7