Abstract

This study aimed to explore the relationship between Bipolar Disorder (BD) and endocrine hormones, as well as the relationship between psychotropics and endocrine hormones. We recruited 55 drug-naïve women patients with BD, 66 long-term medicated women patients with BD, and 53 healthy controls. Serum levels of thyroid hormones, reproductive hormones, and insulin were measured in all participants. Clinical symptoms of depression and mania were measured in all patients with BD. After controlling for confounding factors, drug-naïve patients showed higher levels of free triiodothyronine (FT3), FT3/free thyroxine (FT4), and luteinizing hormone (LH) than controls, and medicated patients showed higher levels of FT3/FT4, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), anti-müllerian hormone (AMH), and insulin than drug-naïve patients. In addition, medicated patients showed a higher prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism (24.24%) than drug-naïve patients (1.82%). In General Linear Model (GLM) analysis, use of lithium was associated with TSH levels (β = 0.22, p = 0.034), and use of antipsychotics was associated with AMH (β = 0.38, p = 0.005) and insulin levels (β = 0.27, p = 0.039). BD itself and its medication treatment are associated with alterations of thyroid and reproductive hormones, suggesting BD may interfere with hormone homeostasis through neuroendocrine mechanisms. Lithium, valproate, and antipsychotics should be prescribed carefully in BD patients with pre-existing hormone abnormalities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bipolar Disorder (BD) is a chronic episodic mental disorder, with a global prevalence of approximately 2%1. It is characterized by recurrent episodes of depression, mania, or hypomania, alternating with periods of stability. BD generally onset during adolescence or early adulthood, and is associated with a high rate of relapse, with an annual recurrence rate of 64% and a 5-year recurrence rate of 72.4%2. To some extent, the significant issue of high medication nonadherence, which ranges from 10–60%3, along with inaccurate treatment4 could be partial contributing factors to the high recurrence rate of BD. The cyclical nature of this disorder imposes a substantial burden on families and society.

Although the pathophysiology of Bipolar Disorder remains unclear, increasing studies have found the relationship between BD and endocrine disturbances, including menstrual abnormality, thyroid dysfunction, and insulin resistance (IR). Patients with mood disorders have a high risk of hypothyroidism, and particularly this association was only confirmed in female individuals, but not in male individuals5. Current research findings regarding the relationship between thyroid dysfunction and BD remain contradictory. One study found that patients with BD were 2.55 times more likely to have thyroid dysfunction6. Another study found that BD patients had a comparable prevalence of hypothyroidism to the general population7. Joffe et al.8 reported that female patients with BD are more likely to experience menstrual dysfunction prior to BD diagnosis than controls. Moreover, BD patients exhibit increased mood vulnerability to fluctuations in reproductive hormones, as demonstrated by Masters et al.9 who found that 54.9% of BD patients experienced at least one mood episode occurrence during hormonal fluctuations (i.e., pregnancy and postpartum period). Available evidence indicates that abnormalities of insulin physiology in BD may mediate the allostatic load, which makes BD patients more vulnerable to stressors and episodes10. Even the mean values of neutrophils, platelets, mean platelet volume, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte, platelet-to-lymphocyte, and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratios are associated with (hypo) mania mood and the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio may be a significant predictor of (hypo) mania episodes11. Several studies have reported that IR and impaired glucose metabolism in BD patients were associated with poor clinical outcomes, including worse cognitive deficits, high risk of developing a rapid cycling course, poor global functioning, and poor treatment response12. Few studies have directly focused on the relationship between BD and insulin secretion.

Psychotropics also play a role in altering endocrine hormones. In women patients with BD, receiving valproate (VPA) was found to be associated with alterations of 17 alpha-OH progesterone, luteinizing hormone: follicle-stimulating hormone ratios, and estrogen13. Mood stabilizers such as VPA and lithium (Li) should be used with caution in women experiencing reproductive events due to potential reproductive issues such as breastfeeding concerns and the risk of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS)14. A cross-sectional study reported that 22% female patients with BD receiving Li showed features of hypothyroidism, while male patients with BD receiving Li showed no abnormality in thyroid hormones15. Antipsychotics such as olanzapine were reported to induce hyperinsulinemia in healthy volunteers16. In BD patients, psychotropics are linked to IR, and this association occurs regardless of the specific type of psychotropic17.

Some studies have separately investigated the levels of reproductive hormones18 thyroid hormones19 and insulin20 in BD patients. However, these studies were unable to completely rule out the effects of psychotropics. We hypothesized that both BD itself and medication used in BD treatment may have effects on altering hormone levels, and medications such as VPA and Li may also influence hormone levels. To explore the influence of BD and psychotropics on endocrine hormones, we compared endocrine hormone levels among drug-naïve BD patients, long-term medicated BD patients, and healthy controls (HC). Due to the keen interest of women with BD in endocrine changes following their medication, we exclusively recruited female participants.

Methods

Participants

From March 2022 to November 2022, patients with BD were recruited from the Department of Psychiatry of Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, located in Changsha, China. The inclusion criteria for these patients were as follows: (1) Female, aged between 16 and 50 years. (2) Meeting the diagnostic criteria for BD as outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), confirmed through the MINI-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) and diagnosed by at least one psychiatrist at the deputy director level or above. (3) Having never received psychotropic medications before participation or having undergone long-term psychotropic medication for at least 6 months. The exclusion criteria for BD patients were: (1) A history of craniocerebral trauma or a diagnosis of neurological or organic mental diseases. (2) Comorbidity with other mental disorders or metabolic and endocrine disorders. (3) A history of psychoactive substance abuse. (4) Current postmenopausal status, pregnant, or lactating. (5) A history of hysterectomy, oophorectomy, or thyroidectomy. (6) Undergoing hormone replacement therapy, including thyroid hormones, glucocorticoids, reproductive hormones, and insulin. Based on these criteria, the recruited patients were categorized into two groups: the drug-naïve BD group and the medicated BD group. The drug-naïve BD group was defined as those who were newly diagnosed with BD for the first time without medication. The PASS 15 software (NCSS, Kaysville, Utah, USA) was used to calculate the required sample size. The type I error of hypothesis test was set at α = 0.05 (two-sided) and the type II error was set at β = 0.10. For previous studies on thyroid function, the prevalence of thyroid abnormalities was 14% in newly diagnosed BD patients and 6% in controls6 and 43.5% in medicated BD patients21. The calculated total sample size is 82, and the sample size for each group is 27. For previous studies on reproductive function, the prevalence of menstrual abnormalities was 50% and 65% in unmedicated and medicated BD patients, respectively13 and 28.75% in the healthy population22. The calculated total sample size is 145, and the sample size for each group is 49.

Female HC were enrolled from nearby communities and universities through advertisements. These subjects should have no history or a family history of mental illness, and should also be free of chronic physical diseases and long-term medication. All participants in the HC group underwent rigorous screening with the M.I.N.I. for DSM-5 criteria to ensure the absence of psychiatric disorders in them and their first-degree relatives. The exclusion criteria for HCs were the same as those for BD patients.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University and was conductedhad in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. All subjects were informed and fully understood the study. Each subject provided a written informed consent.

Demographic and clinical assessment

Demographic data including age, years of education, history of drinking and smoking were collected from all participants. The duration of illness was provided by BD patients. For those patients taken psychotropic drugs, details on the types and doses of drugs were collected. Manic and depressive symptoms of patients with BD were evaluated using clinical scales: the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)23 for mania, and the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17)24 for depression. Referring to previous literature25 we divided the BD patients recruited in this study into three mental status subgroups based on the HAMD-17 and YMRS scores: (1) euthymic: HAMD < 17 and YMRS < 12, n = 17, (2) depressive: (HAMD ≥ 17 and YMRS < 12, (3) manic: HAMD < 17 and YMRS ≥ 12. (4) mixed: HAMD ≥ 17 and YMRS ≥ 12.

Measurement of hormone levels

Blood samples were collected from all participants by venipuncture (5 mL) between 7 a.m. and 9 a.m. after overnight fasting. To ensure the stability of reproductive hormones, we collected blood samples from all the participants on days 2–5 of their menstrual cycles. Since hormone levels during this period are relatively stable, it allows for a more precise and accurate assessment of ovarian function26. Serum was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min and stored at − 80 °C before use. Measurement of hormone levels was conducted in an automatic biochemical analysis system. The hormones include thyroid hormones (free thyroxine (FT4), free triiodothyronine (FT3), and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)), reproductive hormones (luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), prolactin (PRL), estradiol (E2), testosterone II (TST II), progesterone (PRGE), anti-müllerian hormone (AMH)), and insulin. Subclinical hypothyroidism is defined as TSH ≥ 4.5 mIU/L and TSH ≤ 19.9 mIU/L as well as FT4 ≥ 9 pmol/L and FT4 ≤ 22 pmol/L27.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted in R (Version 4.3.1). The data were first checked for normality by one-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and quantile-quantile plot (Q-Q plot). Normal variables (i.e., age) were shown as mean ± SD, and were compared between groups by Student’s t-test. Variables conforming to a non-normal distribution were shown as P50 (P25, P75) and compared using Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were expressed as N (%) and compared using chi-square (χ2) test or Fisher’s exact test. To reduce the impact of confounding factors, General Linear Model (GLM) was used to compare blood hormone levels between groups while controlling demographic and clinical variables that may have possible effects. To analyze the associations between medication and hormones, demographic and clinical variables were also utilized as confounding factors in General Linear Model (GLM). Statistical significance was set at two-tailed p < 0.05.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

We recruited 55 drug-naïve patients, 66 medicated patients, and 53 HC. Comparing among three groups, no significant difference in age (Z = 1.42, p = 0.244) was found, and significant differences in percentage of drinking (χ2 = 12.75, p = 0.002) and smoking history (p = 0.001) were found (Table 1). In the post-hoc comparisons, the drug-naive BD group showed a higher percentage of drinking history than the medicated BD group and HC group, and the two patient groups showed a higher percentage of smoking history than the HC group. When comparing the two patient groups, no significant difference in age of onset was found (Z = 1.53, p = 0.127) and the drug-naive BD group showed shorter duration of illness (Z = 5.76, p<0.001), higher scores of HAMD-17 (Z = 5.99, p<0.001) and YMRS (Z = 3.24, p = 0.001) than the medicated BD group. Significant difference in mental status was also found between the drug-naive BD group and the medicated BD group.

In the medicated BD group, all patients received at least one type of mood stabilizer. Specifically, 65.15% of the patients received VPA, 48.48% received Li, and 15.15% received other mood stabilizers. Furthermore, 86.36% of the patients additionally received antipsychotics, while 19.70% additionally received antidepressants (Supplemental Table 1).

Comparison of endocrine hormones among groups

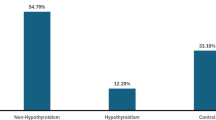

As showed in Table 1, no significant difference in hormones including LH (Z = 4.81, p = 0.090), PRL (Z = 3.90, p = 0.142), E2 (Z = 4.19, p = 0.123), and TST II (Z = 5.15, p = 0.076), and PRGE (Z = 3.09, p = 0.213), and significant differences in FT3 (Z = 8.74, p = 0.013), FT4 (Z = 12.84, p = 0.002), FT3/FT4 (Z = 30.59, p < 0.001), TSH (Z = 20.31, p < 0.001), FSH (Z = 6.91, p = 0.032), LH/FSH (Z = 8.76, p = 0.013), AMH (Z = 18.09, p < 0.001), insulin (Z = 7.47, p = 0.024), and percentage of subclinical hypothyroidism (p < 0.001)were found among the three groups.

In the post-hoc comparisons, the medicated BD group showed lower FT4, as well as higher FT3/FT4, TSH, and percentage of subclinical hypothyroidism than the drug-naïve BD group. The medicated BD group also showed lower FT4 and FSH, as well as higher FT3, FT3/ FT4, TSH, LH/FSH, AMH, insulin, and percentage of subclinical hypothyroidism than the HC group.

After controlling for confounding factors including age, and history of drinking and smoking in GLM, the drug-naïve BD group showed higher FT3 (β = 0.26, p = 0.015), FT3/FT4 (β = 0.21, p = 0.043), LH (β = 0.27, p = 0.010), and LH/FSH ratio (β = 0.27, p = 0.013) than the HC group (Table 2; Fig. 1).

After controlling for confounding factors including age, history of drinking and smoking, and duration of illness in GLM, the medicated BD group showed higher FT3/FT4 (β = 0.32, p = 0.002), TSH (β = 0.30, p = 0.003), AMH (β = 0.30, p = 0.004) and insulin (β = 0.23, p = 0.025) levels than the drug-naïve BD group (Table 2; Fig. 2).

Violin plot of hormones in the drug-naïve BD group and HC group. BD, Bipolar Disorder; HC, healthy control; FT3, free triiodothyronine; FT4, free thyroxine; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; PRL, prolactin; E2, estradiol; TST II, testosterone II; PRGE, progesterone; AMH, anti-Müllerian hormone. Plot based on GLM results, *p<0.05.

Violin plot of hormones in the drug-naïve BD group and medicated BD group. BD, Bipolar Disorder; HC, healthy control; FT3, free triiodothyronine; FT4, free thyroxine; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; PRL, prolactin; E2, estradiol; TST II, testosterone II; PRGE, progesterone; AMH, anti-Müllerian hormone. Plot based on GLM results, *p<0.05.

Association of hormones with types of psychotropics in BD

Among the 66 BD patients, 61 patients (92.42%) were treated with VPA, Li, or a combination of both (Table 3). When comparing the measured hormone levels based on the mood stabilizers used in these 61 patients, no difference was found among the three subgroups.

In the multivariate regression analysis of all 66 medicated patients, different types of psychotropics were treated as independent variables, and the hormones (FT3/FT4, TSH, AMH, and insulin) and percentage of subclinical hypothyroidism with significant difference between the medicated BD group and drug-naïve BD group in GLM analysis were included as dependent variables (Table 4). After controlling for age, duration of illness, and history of drinking and smoking, results showed that Li (β = 0.23, p = 0.032) and other stabilizers (β= −0.21, p = 0.024) treatment were associated with TSH. Mood stabilizers combined with antipsychotics were associated with AMH (β = 0.38, p = 0.005) and insulin (β = 0.27, p = 0.039). Furthermore, VPA (OR (95% CI) = 4.38 (1.09, 17.56), p = 0.037) and Li (OR (95% CI) = 7.19 (1.69, 30.68), p = 0.008) treatment were risk factors for subclinical hypothyroidism.

Discussion

This study revealed significant changes in thyroid hormones and reproductive hormones in drug-naïve patients with BD, suggesting that BD itself may interfere with hormone homeostasis. After controlling for confounding factors, psychotropic medication was found to be associated with TSH, AMH, and insulin. Moreover, VPA and Li were found to be a risk factors for subclinical hypothyroidism.

Thyroid hormones are crucial for individual neurological development and cognitive function28. Studies have shown that hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis dysfunction is associated with the pathophysiology, course, treatment, and outcome of BD, and hypothyroidism seems to be the most prevalent abnormality observed in BD29. The psychiatric symptoms of hypothyroidism include psychomotor retardation, depressed mood, cognitive deficits, decreased appetite, and fatigue30,31 which are similar to the clinical symptoms of bipolar depression. In our study, we found increase of FT3 and FT3/FT4 in drug-naïve BD patients after controlling for confounding factors, which are inconsistent with previous studies21,32,33. To our knowledge, this is the first study comparing FT3/FT4 between drug-naïve BD patients and controls. Wang’s team32,33 reported that TSH levels significantly decreased in unmedicated BD depression, but the findings for FT3 and FT4 were ambiguous. Possible reasons may explain this discrepancy. The first reason is different populations. We focus on the levels of thyroid hormones in female patients, with younger age and shorter duration of disease than those patients of Lai et al.’s study33. Data from a 20-year follow-up cohort reported that the incidence of hypothyroidism was high in women, and the risk of development of hypothyroidism increased with age34. The second reason is different mood states. Wang’s team32,33 explored thyroid hormones in bipolar depression, and our study includes all mood states including depression, mania, mixed state, and remission. Song’s study reported that there were differences in serum T3 and FT3 between bipolar depression and mania/hypomania21. However, this study was conducted in medicated patients, further studies may need to explore the thyroid hormones in different mood states of drug-naïve BD patients.

The adverse effects of Li on thyroid hormones have been widely recognized that Li inhibits thyroidal iodine uptake, iodotyrosine coupling, and secretion of thyroid hormones35. The inhibition of thyroid hormone secretion is essential for the onset of hypothyroidism. One longitudinal study reported that plasma TSH levels of BD increased after starting Li treatment36. And this increase of TSH caused by Li treatment was also confirmed in patients with major depressive disorder37. Another study also reported that Li treatment had the highest incidence of clinical hypothyroidism (10.7%) than other drugs including aripiprazole, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, olanzapine, oxcarbazepine, quetiapine, risperidone, and VPA38. Furthermore, it has also been reviewed that Li can accelerate the progression of pre-existing thyroiditis, particularly in women, potentially leading to the development of hypothyroidism39. Our results were consistent with previous studies, suggesting that it is crucial for women with BD to undergo baseline assessments of thyroid function before starting Li treatment, and to prescribe Li with caution, accompanied by regular long-term monitoring of its effects on thyroid health.

The relationship between BD and reproductive function is complex. On the one hand, Rasgon et al.13. previously found that 50% women reported menstrual abnormalities prior to their diagnosis and treatment of BD, most frequently were 32.5% menorrhagia and 22.5% oligomenorrhea. Changes in reproductive hormones are the basis of menstrual abnormalities. On the other hand, it is consistently reported that a high prevalence of PCOS is found in women with BD. PCOS is a common endocrine and metabolic disorder in women, it is characterized by dysregulated reproductive hormones, including hyperandrogen, increased serum levels of LH, LH/FSH ratio and AMH, as well as decreased FSH, E2, and PRGE40. In community samples, the prevalence of PCOS is estimated to be 8–13%41,42. In women with BD, research has indicated that the prevalence of PCOS was notably high, affecting 23% of a sample of 200 patients43. Previous study also reported that BD patients exhibited menstrual abnormalities and notably high LH/FSH and sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG)44. We observed changes of reproductive hormones in our drug-naïve BD sample similar to PCOS, and the increased LH levels and LH/FSH ratio remained significant after controlling for confounding factors including drinking and smoking. Our results support the high risk of PCOS in drug-naive BD patients, and the changes of reproductive hormones are not solely attributable to the high prevalence of comorbid unhealthy lifestyles in BD45,46. The underlying interpretation of dysregulated reproductive hormones is the interplay and dysfunction between the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) and hypothalamus–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis47. Hyperactivation of the HPA axis was widely reported in BD, with elevated cortisol levels48,49 and enhanced cortisol response to the combined dexamethasone/corticotropin-releasing hormone (dex/CRH) test50,51. The activation of the HPA axis can suppress the activity of the HPG axis, thereby resulting in an increase in androgens released by the adrenal glands in women and a decrease in estrogen levels due to the inhibition of the HPG axis52,53. To better understand how BD influences reproductive function, it is necessary to further explore underlying mechanisms in cytological and animal experiments.

VPA is the most reported drug which can alter reproductive function, including increased prevalence of menstrual irregularities54 increased free androgen index (FAI)55 and increased serum testosterone56 LH and FSH levels57. We did not find associations between VPA and reproductive hormones, but we found significant associations between antipsychotics (combined with mood stabilizers) and AMH and insulin. In this study, 56.06% (n = 37) of the patients receiving antipsychotics were also concurrently prescribed VPA, which may partly explain the significant associations observed between antipsychotics and reproductive hormones. In addition, VPA is also found to be associated with increased risk of PCOS13,54,58. Several studies have found that individuals with PCOS have elevated peripheral blood levels of AMH, LH, and LH/FSH, as well as hyperinsulinemia and IR59,60,61. In this study, we observed higher serum AMH and insulin in medicated BD patients than drug-naïve patients, suggesting an increased risk of PCOS by psychotropic treatment. Studies also found that use of antipsychotic drugs, such as olanzapine and clozapine, is associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome, increasing the risk of PCOS62. Based on the above research results, we hypothesize that the results of association between antipsychotics and reproductive hormones found in our results may represent the combination effects of antipsychotics and VPA on the risk of PCOS.

There are several limitations in our study that cannot be overlooked. The causal relationships between hormones and BD, as well as between hormones and psychotropics, remain inconclusive in this cross-sectional study. A cohort study may uncover the causal link. Additionally, most patients in the medicated BD group were generally young and took more than one kind of psychotropics. Only 5 patients (7.58%) of 66 medicated patients accepted monotherapy of mood stabilizer (VPA or Li) without antipsychotics or antidepressants. Among the 56 patients who used antipsychotics, the sample size of those used monotherapy of antipsychotic was smaller than 20, which is insufficient to accurately determine which specific type of antipsychotics influences hormone levels. Large clinical trials on psychotropics monotherapy in full age range should be conducted in the future. Moreover, we could not rule out the influences of some factors such as diet, lifestyle, exercise, micronutrients status, and exposure to perchlorate63,64,65 which were related to abnormal reproductive and thyroid hormones. Previous studies emphasized the differences of clinical features, illness course, and treatment response between bipolar subtypes (bipolar I and II disorders)66. Notably, these subtype-specific differences may extend to neuroendocrine regulation. However, the present study did not stratify participants by bipolar subtypes, thereby limiting our ability to examine potential subtype-endocrine system interactions. Finally, the hormone levels of our interest can only reflect a portion of the overall thyroid function and ovarian function. We did not collect data on menstrual cycles or conduct pelvic ultrasound examinations for all participants, which are important for diagnosing PCOS.

Conclusion

In conclusion, BD itself and its medication are associated with alterations in thyroid hormones and reproductive hormones. The findings of altered hormones in the drug-naïve BD patients suggest hormonal dysregulation may be an intrinsic characteristic of BD, inspiring research on shared genetic or molecular pathways underlying both BD and hormonal imbalances. Specially, medications include Li and VPA may contribute to subclinical hypothyroidism, and antipsychotics and VPA may contribute to alterations in reproductive hormones. For those BD patients with abnormal thyroid hormones and reproductive hormones before drug initiation, psychotropics should be used with caution and the hormone levels should be monitored regularly.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

References

Nikolitch, K., Saraf, G., Solmi, M., Kroenke, K. & Fiedorowicz, J. G. Fire and darkness: On the assessment and management of Bipolar Disorder. Med. Clin. North. Am. 107, 31–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2022.04.002 (2023).

Jairam, R., Srinath, S., Girimaji, S. C. & Seshadri, S. P. A prospective 4–5 year follow-up of juvenile onset Bipolar Disorder. Bipolar Disord. 6, 386–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00149.x (2004).

Pompili, M. et al. Improving adherence in mood disorders: The struggle against relapse, recurrence and suicide risk. Expert Rev. Neurother. 9, 985–1004. https://doi.org/10.1586/ern.09.62 (2009).

Nasrallah, H. A. Consequences of misdiagnosis: Inaccurate treatment and poor patient outcomes in Bipolar Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 76, e1328. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14016tx2c (2015).

Bode, H. et al. Association of hypothyroidism and clinical depression: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 78, 1375–1383. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2506 (2021).

Krishna, V. N. et al. Association between bipolar affective disorder and thyroid dysfunction. Asian J. Psychiatr. 6, 42–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2012.08.003 (2013).

Menon, B. Hypothyroidism and bipolar affective disorder: Is there a connection? Indian J. Psychol. Med. 36, 125–128. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.130966 (2014).

Joffe, H. et al. Menstrual dysfunction prior to onset of psychiatric illness is reported more commonly by women with Bipolar Disorder than by women with unipolar depression and healthy controls. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 67, 297–304. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v67n0218 (2006).

Masters, G. A. et al. Prevalence of Bipolar Disorder in perinatal women: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.21r14045 (2022).

Brietzke, E. et al. Insulin dysfunction and allostatic load in Bipolar Disorder. Expert Rev. Neurother. 11, 1017–1028. https://doi.org/10.1586/ern.10.185 (2011).

Fusar-Poli, L. et al. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte, Platelet-to-Lymphocyte and Monocyte-to-Lymphocyte ratio in Bipolar Disorder. Brain Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11010058 (2021).

Miola, A. et al. Insulin resistance in Bipolar Disorder: A systematic review of illness course and clinical correlates. J. Affect. Disord. 334, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.04.068 (2023).

Rasgon, N. L. et al. Reproductive function and risk for PCOS in women treated for Bipolar Disorder. Bipolar Disord. 7, 246–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00201.x (2005).

Freeman, M. P. & Gelenberg, A. J. Bipolar Disorder in women: Reproductive events and treatment considerations. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 112, 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00526.x (2005).

Kraszewska, A., Chlopocka-Wozniak, M., Abramowicz, M., Sowinski, J. & Rybakowski, J. K. A cross-sectional study of thyroid function in 66 patients with Bipolar Disorder receiving lithium for 10–44 years. Bipolar Disord. 17, 375–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12275 (2015).

Toledo, F. G. S. et al. Insulin and glucose metabolism with olanzapine and a combination of olanzapine and samidorphan: Exploratory phase 1 results in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology 47, 696–703. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-021-01244-7 (2022).

Kenna, H. A., Jiang, B. & Rasgon, N. L. Reproductive and metabolic abnormalities associated with Bipolar Disorder and its treatment. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry. 17, 138–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/10673220902899722 (2009).

Lyu, N. et al. Hormonal and inflammatory signatures of different mood episodes in Bipolar Disorder: A large-scale clinical study. BMC Psychiatry. 23, 449. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04846-1 (2023).

Liu, S., Chen, X., Li, X. & Tian, L. Thyroid hormone levels in patients with Bipolar Disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Endocr. Disord. 24, 248. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-024-01776-1 (2024).

Rasgon, N. L. et al. Metabolic dysfunction in women with Bipolar Disorder: The potential influence of family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Bipolar Disord. 12, 504–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00839.x (2010).

Song, X., Feng, Y., Yi, L., Zhong, B. & Li, Y. Changes in thyroid function levels in female patients with first-episode Bipolar Disorder. Front. Psychiatry. 14, 1185943. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1185943 (2023).

Dhar, S., Mondal, K. K. & Bhattacharjee, P. Influence of lifestyle factors with the outcome of menstrual disorders among adolescents and young women in West bengal, India. Sci. Rep. 13, 12476. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35858-2 (2023).

Young, R. C., Biggs, J. T., Ziegler, V. E. & Meyer, D. A. A rating scale for mania: Reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br. J. Psychiatry. 133, 429–435. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.133.5.429 (1978).

Hamilton, M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 23, 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56 (1960).

Zhou, T. H. et al. Clinical efficacy, onset time and safety of bright light therapy in acute bipolar depression as an adjunctive therapy: A randomized controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord. 227, 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.038 (2018).

Hansen, L. M. et al. Evaluating ovarian reserve: Follicle stimulating hormone and oestradiol variability during cycle days 2–5. Hum. Reprod. 11, 486–489. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/11.3.486 (1996).

Cappola, A. R. et al. Thyroid status, cardiovascular risk, and mortality in older adults. Jama 295, 1033–1041. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.9.1033 (2006).

Prezioso, G., Giannini, C. & Chiarelli, F. Effect of thyroid hormones on neurons and neurodevelopment. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 90, 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1159/000492129 (2018).

Chakrabarti, S. Thyroid functions and bipolar affective disorder. J. Thyroid Res. 2011, 306367 https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/306367 (2011).

Bauer, M., Glenn, T., Pilhatsch, M., Pfennig, A. & Whybrow, P. C. Gender differences in thyroid system function: Relevance to Bipolar Disorder and its treatment. Bipolar Disord. 16, 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12150 (2014).

Samuels, M. H. & Bernstein, L. J. Brain fog in hypothyroidism: What is it, how is it measured, and what can be done about it. Thyroid 32, 752–763. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2022.0139 (2022).

Zhong, S. et al. Correlation between intrinsic brain activity and thyroid-stimulating hormone level in unmedicated bipolar II depression. Neuroendocrinology 108, 232–243. https://doi.org/10.1159/000497182 (2019).

Lai, S. et al. Association of altered thyroid hormones and neurometabolism to cognitive dysfunction in unmedicated bipolar II depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 105, 110027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110027 (2021).

Vanderpump, M. P. et al. The incidence of thyroid disorders in the community: A twenty-year follow-up of the whickham survey. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 43, 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.1995.tb01894.x (1995).

Lazarus, J. H. The effects of lithium therapy on thyroid and thyrotropin-releasing hormone. Thyroid 8, 909–913. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.1998.8.909 (1998).

Lombardi, G. et al. Effects of lithium treatment on hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis: A longitudinal study. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 16, 259–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03348825 (1993).

Bschor, T. et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid system activity during lithium augmentation therapy in patients with unipolar major depression. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 28, 210–216 (2003).

Lambert, C. G. et al. Hypothyroidism risk compared among nine common Bipolar Disorder therapies in a large US cohort. Bipolar Disord. 18, 247–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12391 (2016).

Lazarus, J. H. Lithium and thyroid. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 23, 723–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2009.06.002 (2009).

Emanuel, R. H. K. et al. A review of the hormones involved in the endocrine dysfunctions of polycystic ovary syndrome and their interactions. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 1017468. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1017468 (2022).

March, W. A. et al. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample assessed under contrasting diagnostic criteria. Hum. Reprod. 25, 544–551. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dep399 (2010).

Azziz, R. et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2, 16057. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.57 (2016).

Qadri, S., Hussain, A., Bhat, M. H. & Baba, A. A. Polycystic ovary syndrome in bipolar affective disorder: A Hospital-based study. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 40, 121–128. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpsym.Ijpsym_284_17 (2018).

Reynolds-May, M. F. et al. Evaluation of reproductive function in women treated for bipolar disorder compared to healthy controls. Bipolar Disord. 16, 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12149 (2014).

Pozzolo Pedro, M. O., Pozzolo Pedro, M., Martins, S. S. & Castaldelli-Maia, J. M. Alcohol use disorders in patients with Bipolar Disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Rev. Psychiatry. 35, 450–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2023.2249548 (2023).

Heffner, J. L., Strawn, J. R., DelBello, M. P., Strakowski, S. M. & Anthenelli, R. M. The co-occurrence of cigarette smoking and Bipolar Disorder: Phenomenology and treatment considerations. Bipolar Disord. 13, 439–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00943.x (2011).

Dai, W. et al. Shared postulations between Bipolar Disorder and polycystic ovary syndrome pathologies. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 115, 110498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110498 (2022).

Schmider, J. et al. Combined dexamethasone/corticotropin-releasing hormone test in acute and remitted manic patients, in acute depression, and in normal controls: I. Biol. Psychiatry. 38, 797–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3223(95)00064-x (1995).

Belvederi Murri, M. et al. The HPA axis in Bipolar Disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 63, 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.10.014 (2016).

Watson, S., Gallagher, P., Ritchie, J. C., Ferrier, I. N. & Young, A. H. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in patients with Bipolar Disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry. 184, 496–502. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.184.6.496 (2004).

Watson, S., Gallagher, P., Smith, M. S., Young, A. H. & Ferrier, I. N. Lithium, arginine vasopressin and the dex/crh test in mood disordered patients. Psychoneuroendocrinology 32, 464–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.02.010 (2007).

Castañeda Cortés, D. C., Langlois, V. S. & Fernandino, J. I. Crossover of the hypothalamic pituitary-adrenal/interrenal, -thyroid, and -gonadal axes in testicular development. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 5, 139. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2014.00139 (2014).

Swaab, D. F., Bao, A. M. & Lucassen, P. J. The stress system in the human brain in depression and neurodegeneration. Ageing Res. Rev. 4, 141–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2005.03.003 (2005).

McIntyre, R. S., Mancini, D. A., McCann, S., Srinivasan, J. & Kennedy, S. H. Valproate, Bipolar Disorder and polycystic ovarian syndrome. Bipolar Disord. 5, 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-5618.2003.00009.x (2003).

Stephen, L. J., Kwan, P., Shapiro, D., Dominiczak, M. & Brodie, M. J. Hormone profiles in young adults with epilepsy treated with sodium valproate or lamotrigine monotherapy. Epilepsia 42, 1002–1006. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.0420081002.x (2001).

Akdeniz, F., Taneli, F., Noyan, A., Yüncü, Z. & Vahip, S. Valproate-associated reproductive and metabolic abnormalities: Are epileptic women at greater risk than bipolar women? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 27, 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0278-5846(02)00341-x (2003).

Rättyä, J. et al. Early hormonal changes during valproate or carbamazepine treatment: A 3-month study. Neurology 57, 440–444. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.57.3.440 (2001).

Bilo, L. & Meo, R. Polycystic ovary syndrome in women using valproate: A review. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 24, 562–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590802288259 (2008).

Dewailly, D. et al. The physiology and clinical utility of anti-Mullerian hormone in women. Hum. Reprod. Update. 20, 370–385. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmt062 (2014).

Macut, D., Bjekić-Macut, J., Rahelić, D. & Doknić, M. Insulin and the polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 130, 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2017.06.011 (2017).

Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 81, 19–25 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.004 (2004).

Doretto, L., Mari, F. C. & Chaves, A. C. Polycystic ovary syndrome and psychotic disorder. Front. Psychiatry. 11, 543. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00543 (2020).

Escobar-Morreale, H. F. Polycystic ovary syndrome: Definition, aetiology, diagnosis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 14, 270–284. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2018.24 (2018).

Gustin, K. et al. Assessment of joint impact of iodine, selenium, and zinc status on women’s Third-Trimester plasma thyroid hormone concentrations. J. Nutr. 152, 1737–1746. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxac081 (2022).

Babić Leko, M., Gunjača, I., Pleić, N. & Zemunik, T. Environmental factors affecting thyroid-Stimulating hormone and thyroid hormone levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22126521 (2021).

Brancati, G. E. et al. Differential characteristics of bipolar I and II disorders: A retrospective, cross-sectional evaluation of clinical features, illness course, and response to treatment. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 11, 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-023-00304-9 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank all subjects who served as research participants.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants Nos.: 81971258) and Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos.: 2025JJ80494).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Y. did formal analysis of the data and wrote the original draft. Y.F. and C.J. did data collection and methodology of this study. M.L. and J.C. contributed to review and editing of the draft. J.L. provided the conceptualization of this study and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, M., Fu, Y., Jiang, C. et al. Independent and medication related effects of bipolar disorder on thyroid and reproductive hormones in women. Sci Rep 15, 26962 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11460-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11460-6