Abstract

Waveguides and transitions provide efficient, low-loss microwave transmission across a target frequency band for space communications and radar. However, traditional waveguide transitions suffer from impedance mismatch, higher-order mode excitation, field distortion, and complex-geometry fabrication constraints. This study addresses these issues by developing a Ku-band low-cost coaxial-to-circular waveguide transition prototype, fabricated by Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF), followed by electroless-metallization. We present a novel coaxial-to-rectangular-to-elliptical-to-circular transition topology with an integrated septum for a split-waveguide structure. The entirely conductive PLA filament-based 3D-printed structure with subsequent silver-epoxy metallization features an E-plane cut halves, employing optimized 3D-printing and geometric design parameters. The hybrid design simplifies manufacturing, streamlines metallization, and enhances RF performance through suppressing higher-order modes by 25 dB, improving return loss to better than − 15 dB, reducing attenuation to as low as 0.145dB/m, minimizing electromagnetic discontinuities, and increasing polarization isolation by 30dB for linearly-polarized applications while ensuring smooth field propagation. The lightweight, cost-effective design enables early testing and highlights future implementation with space-grade materials like PEEK/Ultem® that could enable rugged, low-mass alternatives to conventional waveguides. These findings empower a sustainable approach to custom small-scale LEO small-satellite RF systems by using additive manufacturing to reduce costs, material waste, conserve resources, and lower launch mass and energy requirements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Waveguides and transitions provide efficient Electromagnetic (EM) wave transmission while integrating with RF chain microwave or millimeter-wave systems elements such as mixers, amplifiers, filters, resonators, or antenna feeds for satellite communications and space radar systems1,2. Hollow metallic waveguides are preferred due to their low-loss properties, relatively high power-handling capacity, and effective electromagnetic (EM) shielding3. Direct coaxial feeding of waveguides often leads to narrow bandwidth, poor impedance matching, reduced efficiency, and mode excitation issues due to imprecise probe placement4,5. Therefore, converting coaxial transverse electromagnetic (TEM) signals into waveguide modes and facilitating transitions between various waveguide geometries are critical for impedance matching, reflection reduction, and higher-order mode suppression.

Compared to their broadband rectangular counterparts in6 and the reduced-height version in7, Coaxial-to-Circular waveguide (CCWG) transitions have been less explored. Traditional designs for CCWG transitions, such as the stepped designs aim to provide better mode isolation but suffer from electromagnetic discontinuities8. The broadband tapered CCWG transition achieves low reflection and transmission losses across a wide frequency range but with longer dimensions9. An in-line CCWG transition was reported in10, featuring an asymmetric E- and H-plane spline taper, a four-step ridge TEM launcher (an enhancement of the probe in11), and a multi-section staggered-waveguide transformer. Though longer and complex to fabricate, the combination broadens bandwidth, suppresses higher-order modes, and achieves a low-ripple Chebyshev response over an octave band. Another octave-bandwidth, complex to fabricate, CCWG transition featuring intermediate octagonal shape provides efficient mode conversion capabilities, as reported in12. Lastly, direct conical coaxial-rectangular-circular waveguide transitions offer accurate mode conversion but struggle to achieve a wide bandwidth and low reflection losses at shorter lengths13.

While traditional fabrication methods, such as CNC milling and die casting, etc., offer recycling (e.g., shavings, dust, re-melted diecast), they still incur significant logistical burdens due to scrap reprocessing. Moreover, these methods also struggle to produce complex geometries directly and are only economical at large production scales. In contrast, Additive Manufacturing (AM) incurs no volume-dependent overhead, enabling custom complex parts in a single build without specialized tooling or fixtures.

AM has emerged as a transformative technology, particularly in the space industry, enabling the fabrication of components from small antennas and waveguides to large structures like SpaceX’s Raptor 3 engine as shown in Fig. 1a,b. Therefore, it allows highly compact, detailed, optimized designs once impossible with traditional manufacturing.

Among the various AM techniques, metallic 3D-printing methods like laser sintering enable the production of durable, high-quality microwave components with complex geometries, making them highly effective for space microwave applications. Examples include, the use of 3D-printed air substrates in the design and fabrication of RF components, as reported in14 and advanced RF and microwave passive circuits, as further demonstrated in15. However, metallic 3D printing often produces surface roughness, impairing performance, especially at higher frequencies where precision is crucial16. Though it can be treated through post-processing techniques, it may have limitations of cost and surface defects17. Additionally, metal-based components are typically heavy, which is a significant drawback for applications where weight and compactness are critical. To address the aforementioned challenges, a hybrid approach using plastic polymer-based 3D printing with metallization post-processing has emerged, offering smoother surfaces, reduced weight, and comparable RF performance to metal waveguides even at higher frequencies18,19.

Plastic polymer-based 3D printing methods, such as FFF, Selective Laser Sintering (SLS), Stereolithography Apparatus (SLA), and Polyjet, can be combined with metallization post-processing as hybrid approaches to create viable alternatives for fabricating microwave components. For instance, SLA has been explored for fabricating electroless copper-metalized waveguides in the 75–110 GHz range20, demonstrating its potential for satellite communication components due to low loss, particularly at 60 GHz, though fragility remains a limitation. To improve mechanical robustness, resin formulations can be tailored, and UV post-curing used to complete polymerization, consolidate interlayer bonds, and increase tensile strength while reducing brittleness. However, consistent material properties can only be achieved if production quality is maintained during post-processing21.

In contrast, FFF emerged as a more versatile option for waveguide and other RF components manufacturing22. FFF offers a wide range of material selection, including composites with conductive fillers, such as conductive PLA, and is relatively easier to metallize without resin post-processing compared to SLA, generally leading to parts with more stable material properties. FFF-printed parts, with minimal surface finishing, enable rapid prototyping and functional products23. For instance, Filonov et al.24 demonstrated FFF for fabricating volumetric spiral and Yagi-Uda antennas, using electrochemical metallization of a conductive graphene-PLA patch structure embedded in nonconductive PLA substrate.

For extremely high-frequency applications, SLS is preferred due to its ability to achieve a superior surface finish on smaller parts, though at a higher cost. Minimize losses at E-band frequencies for SLS components reported in25. However, SLS-printed parts require polishing, which can increase manufacturing time, making them more viable for low-volume, high-performance applications. Metalized microwave components fabricated using Polyjet polymer technology, as reported in26, achieved over 50% weight reduction and were cost-effective compared to their metal counterparts. Indeed, suitable for rapid prototyping, but Polyjet may not offer the same level of material strength as other methods. For instance, in27 Polyjet low-cost microwave passive components showcase their potential for space-constrained design but have limitations of unstable material strength performance. Polyjet-printed electroless silver-metallized elliptical waveguide filters of the study highlighted internal support removal challenges, recommending monolithic designs below 12 GHz for electroplating or sputtering. For frequencies above 12 GHz, split structures or visual control are advised to prevent arcing due to small closed structures.

Among the AM methods, FFF stands out as the most practical simple option for low frequency range, low-cost, lightweight, and consistent waveguide manufacturing method under uniform printing conditions. Its wide supported range of filaments including those with conductive nature, ease of post-processing, and repeatability makes it ideal for prototyping and low-cost applications. While SLA, SLS, and Polyjet all have their niches, FFF offers a balanced trade-off for many microwave and waveguide space applications.

FFF-based 3D printed parts exhibit slight roughness due to post-deposition filament characteristics, nozzle dimensions, and thermal conditions. However, this can be mitigated by optimizing printing conditions and laser polishing for smooth surfaces, as detailed in28,29. The use of chloroform smoothing with FFF, despite its higher handling cost, can also reduce surface roughness by ~ 50% and effectively lower insertion loss, as presented in30. Nevertheless, any minute roughness that persists can be covered through various metallization techniques, such as Ti/Cu electroplating31, Electroless Nickel plating with electroplated Cu11, Copper and silver paints32, aluminum foiled33, Liquid gallium metal filling34, Galvanized copper35, Silver electroplating36,37, multistep chemical plating36, and Copper sulfate electroplating38 etc. However, advancements in complexity and quality correlate with increased cost. Electroless silver metallization provides superior conductivity and minimal signal loss, making it an ideal material for communication and radar applications36. For cost-effective implementation copper plating38 or copper/silver paints32 are practical alternatives, while electroless Nickel or galvanized copper11,35 excel in durability for harsh environments. Moreover, various research studies have reported that waveguides with an E-plane cut can mitigate performance degradation caused by surface roughness without disrupting EM surface current lines, thereby reducing losses and improving fabrication tolerances. However, symmetry requirements can impose design limitations26,39.

Conventional waveguide transitions, often optimized for larger bandwidth, are typically oversized and overweight. This presents several drawbacks for custom radar applications, including interference from higher-order modes, loss of mode purity, and impedance mismatch. Furthermore, achieving stable linear polarization with radial or tangential fields in a Circular Waveguide (CWG) necessitates additional components like attenuators or polarizers, which introduce coupling losses. These issues highlight the significant limitations of standard adapters for narrow-band radar systems on envelope-constrained platforms such as CubeSats and small satellites, which require compact and lightweight solutions.

This study proposes a low cost, lightweight custom 3D-printed CCWG transition for a single polarization circular-horn antenna feed in order to provide mode free symmetric illumination for radar reflector applications, especially for small satellite and CubeSat. The proposed CWG features a smooth transformation from coaxial to rectangular to elliptical to circular, ensuring gradual mode conversion, minimal reflection, and improved impedance matching. A ridge-step septum structure in the CWG section suppresses the orthogonal TE11x polarization component, enabling stable linear polarization in the TE11y mode. Stepped septum is employed due to its compactness, wider bandwidth, better impedance matching, ease of fabrication, and simulation efficiency, advantages that outweigh their inherently lower power handling compared to profiled septum, if carefully optimized40.

To the best of our knowledge, a key innovation of this work is the first-time use of a low-cost conductive PLA-based lightweight E-plane split waveguide structure, combined with silver electroless metallization and an integrated septum, for a 3D-printed linear-polarized coaxial-to-rectangular-elliptical-circular waveguide transition topology using FFF. It is particularly suitable for small satellites with lower power requirements than metal waveguides in larger satellites, under Technology Readiness Level-TRL6 conditions, otherwise, space-grade filaments and coatings will be used instead.

Thus, proposed novel design customized approach offers significant improvements in manufacturing, linear robust polarization, compact multi-component assembly, lightweight, low-cost, reduced complexity benchmark performance Engineering Model (EM) with experimental validation.

PLA for space application: rationale

Use conductive PLA for this proof-of-concept design aligns with NASA’s established guidelines41, which states that “PLA is acceptable for applications involving very short-term exposure to well-characterized and controlled harsh conditions, up to TRL6”. This guidance forms a cornerstone of our decision to use PLA, especially conductive PLA, because its ESD-compatible properties mitigate ESD risk. Beyond NASA’s specific criteria, the feasibility of using PLA for CubeSat structures has been widely demonstrated in42. Prior research includes various PLA-based CubeSat structures, such as proof-of-concept CubeSat bus structures43,44 and their hybrid variations45, as well as PLA-based patch antenna design for CubeSat in46. The inclusion of MakerBot PLA (GSC35082) in NASA’s outgassing database further strengthens its potential for space applications47.

The viability of PLA in space environments has been experimentally validated through astronaut Scott Kelly’s testing of 3D-printed PLA parts aboard the International Space Station (ISS). However, these applications were limited to non-functional tooling. This demonstration provides practical evidence of PLA’s potential for space utilization48. Additional motivations for our choice stem from various design concepts and prototypes. These include a PLA-based model, Can-sized suborbital satellites49 and PLA-based prototype antennas and waveguides designed for space applications in50. Moreover, the increasing availability of FFF-processable space-grade filaments like PEI/PC (e.g., Ultem® 9085, 1010), ABS, PEEK/PEKK, and polyethylene (PE/UHMWPE), along with TRL6-qualified PLA material itself, makes FFF an attractive and cost-effective method for rapid prototyping51. In addition, PEI-based filaments like Ultem® 1010 variants with ESD properties are being used for space satellite battery packs developed by Pumpkin Space52. Furthermore, this approach also aligns with current research trends exploring PLA composites incorporating fillers such as graphene nanoplatelets (GNP) and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT), a step toward making this material more robust for space applications53.

Our choice of conductive PLA is thus a strategic decision rooted in established guidelines, empirical evidence, and a forward-looking perspective on materials and manufacturing in space, though practical considerations remain. Nevertheless, the temperature cycles experienced by LEO satellites range from − 65 °C to + 125 °C (with cycles per year depending on orbital altitude)54, while payload temperature typically varies between − 20 °C and + 60 °C37. These conditions favor the use of ULTEM® 9085 or 1010 filament-based waveguides, finished with high-temperature conductive silver coatings, such as Thales SESO Silver or SHIELD™ Silver Conductive Paint 842AR, as a rugged future space grade lightweight design55,56. The remaining environmental controls, including thermal insulation, UV shielding, micrometeoroid protection, and radiation shielding, will be handled by the spacecraft’s bus system, for example, Tyvak, SPUTNIX, etc.

Design configuration and propagation modes

Design configuration

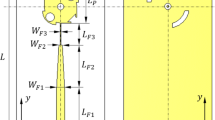

The proposed silver-coated waveguide transition orthographic and isometric views are shown in Fig. 2a–d exhibit TEM-TE10-TE11 mode conversion. The elliptical section of the transition ensures a seamless and gradual transformation from the RWG TE10 mode to the CWG TE11 mode, maintaining impedance matching and minimizing reflections. This transition is specifically designed to support the TE11y mode while effectively suppressing undesired modes such as TE11x, TM01, TE01, TE21, and TM11, ensuring robust polarization performance and enhanced bandwidth. It incorporates a novel ridge metallic septum positioned within the CWG section to achieve polarization robustness and suppress higher-order modes. The ridge septum is centrally located along the input-to-output axis of the CWG and features a step design with a space at its highest point, allowing the TE11y mode to propagate while blocking the TE11x mode. The overall profile dimensions, including the ridge septum height, thickness, position, and rectangular-elliptical transformation, have been meticulously optimized using Genetic Algorithm (GA) and validated through EM simulations in the High-Frequency Structure Simulator (HFSS).

Figure 3a,b illustrates the electric-field distribution and mode evolution at various cross-sections along the waveguide transition, confirming suppression of the TE11x mode and transmission of the desired TE11y mode. A coaxial probe inserted into the RWG initially excites a TEM mode, inducing a radial electric field. This TEM mode is then converted into the dominant TE10 mode of the RWG. Through seven consecutive smooth elliptical sections, the waveguide cross-section transforms into a CWG, preserving single-polarization TE11y. During transmission, only the y-polarized TE10 field is launched; the elliptical taper renders the orthogonal TE11x mode evanescent, allowing pure TE11y propagation. This gradual geometric transformation minimizes reflections and loss, ensuring efficient mode conversion and maintaining the integrity of the field within the CWG. Figure 3c,d illustrate field distributions in the proposed silver-coated waveguide with a septum. A septum polarizer at the circular throat provides additional suppression of any residual TE11x, ensuring significant polarization discrimination for high-fidelity signal transmission. The Fig. 3c,d depict the field intensity and direction, using red for stronger and blue for weaker components. The septum’s influence is evident in the bending and weakening of X-polarized field lines as they approach the septum. This performance extends to reception, maintaining high polarization purity for incoming signals and contributing to robust, efficient conversion across the operating bandwidth.

Waveguide propagation modes and cutoff frequencies

The proposed silver-coated waveguide transition has four main sections, shown in Fig. 2d which are (TREC-TEM-Rectangular-Elliptical-Circular). In a coaxial cable, the fundamental mode is the TEM mode with a cutoff frequency of zero, and the next three higher-order modes, TE11, TE21, and TE31, have their cutoff frequencies given as follows in (1) and (2).

where \(\:{X}_{cmn}\:\)are the first positive roots of the transcendental boundary equation given as follows

for m = 1, TE11 mode yields Xc11 = 1.878 and m = 2, TE21 mode yields Xc21 = 1.032. Here, c is the speed of light in vacuum, and εrc = 2.08 is the dielectric constant of the coaxial cable material filling.

For CWG Modes, the cutoff frequency is given by

where \(\:{\text{X}}_{mn}\) are the Bessel-function roots for example, X11: TE11 = 1.84118, X01: TM01 = 2.40483, X21: TE21 = 3.05424 and X01: TE01 = 3.83171 etc. \(\:{a}_{\text{circ}}\) is the CWG radius 16.2 mm, \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{r}\) is the relative permittivity of free space, and (m) and (n) are the mode indices.

Similarly, for an air-filled RWG of broad-wall a and narrow-wall b, the cutoff frequency is given by (5)10.

Elliptical waveguides having semi-major axis (a) , semi-minor axis (b) and eccentricity (ec) support only TE and TM modes. With mode as TEcm, n and TEsm, n (cosine-even or sine-odd) and TMcm, n and TMsm, n. Where (m) is the angular index around the elliptical circumference, and (n) is the nth radial root for that angular variation along the semi-major axis. The dominant mode is typically the TE mode, analogous to the mode in a CWG. But the degenerate modes in a CWG here split into distinct even/odd modes in an ellipse as the symmetry is reduced.

Analytically determining cutoff frequencies in an elliptical waveguide entails solving the Helmholtz equation in elliptical coordinates and enforcing boundary conditions, which leads to Mathieu function eigenvalues. Although previous analytical forms have been reported in57,58,59, closed-form formulas for determining cutoff frequencies in elliptical waveguides are not generally available. The only way to find the discrete solutions of Mathieu’s equations is either by analytical expansions or numerical root-finding that satisfy the mode quantization and boundary conditions. These solutions yield the cutoff frequencies for the TEm, n and TMm, n modes of the elliptical waveguide. In the presented design study, HFSS is utilized for overall optimization, which numerically solves Mathieu-function roots within the EM simulation environment, thereby facilitating the tuning of the structure. However, for the basic analytical approximation60 RF tool is utilized for the calculation of the elliptical section cutoff frequencies, whose analytical form is given by (6) and (7). Consolidated Cutoff frequency for each of the waveguide sections listed in Table 1.

Simulation and experiment

Design simulation

The proposed silver metallized CWG transition is designed and simulated at the operating frequency fo = 13.6 GHz using EM simulation software HFSS with dimensions mentioned in Table 2. It provides important key dimensions, such as the diameter of the waveguide transition (e), which corresponds to the cutoff frequency, and the thickness of the septum sheet (S_thick), which is around 0.5 mm. Three readily available commercial market surface coatings, silver isopropyl epoxy coating, copper conductive paint, and aluminum foil, have been used for metallization realization in simulation and experiment. To ensure optimal performance of the metalized plastic waveguide, the thickness of the metal coating should exceed seven times the skin depth (\(\:{\updelta\:}\)) of the metal at the operational frequency61. The (\(\:{\updelta\:}\)) of conductor material expressed by (8) and the required threshold metal coating thicknesses for each material under investigation in this study are comprehensively listed in Table 3.

where \(\:\omega\:=\:2\pi\:f\), \(\:{\mu\:\:=\:{\mu\:}_{\text{r}}\mu\:}_{0},\:\:{\mu\:}_{0}=4\pi\:\times\:{10}^{-7}\hspace{0.17em}\text{H}\text{/}\text{m}\), \(\:{\mu\:}_{\text{r}}\) relative permeability of material ≈ 1.

Simulated layer thickness should be equal to or greater than the threshold metal thickness. Thus, simulation parameters are determined based on the indirect material properties provided by the supplier, with additional consideration given to the applied layer thickness. The optimal number of coating layers, determined through experimental trials, was found to be four. This configuration consistently produced the most uniform surface coating, whereas fewer layers left residual traces, and additional layers disrupted the coating’s quality. Therefore, the four-layer coating was selected as the optimal configuration for the simulation and fabrication62. For the metallic copper spray paint, the dry paint thickness and its sheet resistance given by the supplier are (< 1 ohm for 12 cm x 5 cm x 20 μm). Similarly, for the silver isopropyl epoxy paint, the dry paint thickness and its sheet resistance, given by the supplier, are (< 0.04 ohm for 60 mm x 15 mm x 25.4 μm). Resistivity \(\:\left(\rho\:\right)\) is first determined based on the sheet resistance (Rs) provided by the supplier, as defined by the (9). Conductance (σ) is then calculated using standard relationships derived from the material’s resistivity, as defined by (10).

where (W) and (L) are the length and width of the thin sheet, (t) is the thickness, and (R) is the resistance calculated through the four-probe method given by the supplier. Overall values used in the simulation study are listed in the Table 4.

Conductive PLA supplier-provided properties information was utilized in the simulation study, specifically a 150 KΩ resistance per 100 mm and a density of 1.24 g/cm2, which leads to ≈ 0.277 s/m using (10). The diameter of the filament is 1.75 mm. Regarding simulations, a modal network analysis solution type with an auto-open region radiation boundary condition was employed in HFSS. A single-frequency driven solution with a maximum delta-S of 0.01 was used to ensure accurate and converged results. Initial mesh settings include auto-meshing, curvilinear meshing for curved surfaces, and dynamic fine surface resolution for precise simulation results. A 0.01 ghz frequency sweep was employed in the simulation setup. A real SMA connector model of Youwu microwave SMA-KFD8.3T was used in the simulations. Figure 4a illustrates the simulated mode conversion efficiencies and reflection coefficient performance of three different material-coated waveguide transitions, i.e., aluminum foil, copper, and silver epoxy coating. At an operating frequency of 13.6 ghz, the simulated transmission coefficient efficiency for the desired TE11y mode is 99.60%, 97.4% and 89.20% for silver epoxy, aluminum foil, and copper, respectively. Additionally, the Ku-band radar frequency spectrum (13.4–13.75 GHz) is shown in the blue-shaded region. For all materials, the reflection coefficient of the TE11x mode, leading to enhanced polarization stability across both the operation and beyond the operation frequency band. In contrast, the transition without the septum transmits a significant portion of the input power in the undesired TE11x mode, thereby reducing polarization stability and resulting in power division between the two orthogonal polarization components. The septum effectively suppresses the coupling of undesired higher modes by − 25dB, such as TE01, TM11, TM01, and TE21, thereby improving the overall efficiency of the waveguide transition. Figure 4c illustrates the transmission coefficients of various higher-order modes in a silver-coated CWG transition. Overall, the simulated transition performance results summary for different metallization coatings is listed in Table 5.

Figure 5a–d depicts top and side views of the simulated electric and magnetic field distributions within the back-to-back Ag-waveguide transition, revealing regions of high field concentration, field orientation, and propagation direction across the transition. The symmetric distribution of the fields indicates efficient power transfer between the two ports. The E-field aligns with the y-axis, confirming the propagation of the fundamental TE11y mode. The H-field vectors are perpendicular to the E-field, further validating the mode purity and efficient power transfer.

Monte Carlo dimensional tolerance analysis in HFSS was employed to statistically evaluate the Ag-coated transition design performance with dimensions mentioned in Table 2 perturbed by a 0.5% FFF tolerance using Gaussian distributions64. A total of 50 iterations were conducted to assess the impact on the reflection coefficient, transmission coefficient, and higher-order modes at 13.6 GHz. Figure 6 shows the heatmap for the simulated statistical analysis, which illustrates that the reflection coefficient S11 values are well within the acceptable range of − 20 dB to − 40 dB, indicating good impedance matching and minimal signal loss due to reflection under manufacturing tolerances and potential assembly variations. The higher-order modes, including TM01, TE21, TE01, and TM11, all exhibit values below − 40 dB, indicating a negligible impact on the system’s overall performance even under fabrication tolerances. Therefore, the dominant TE11y mode functions efficiently, and the system operates with minimal undesired modes.

A detailed study in65 reveals that microscale surface roughness must be limited to Rx ≤ 200 μm to avoid severe performance degradation. Under this worst-case constraint, the acceptable reflection coefficient remains below − 15 dB, and the total insertion loss is below 0.3 dB (0.075 dB/cm), which sets the permissible limit for waveguide performance. An ideal waveguide, by contrast, exhibits an insertion loss of − 0.2 dB (0.05 dB/cm).

Following the surface-roughness limits reported in65 for W-band waveguides, we performed an additional dimensional tolerance incorporating absolute peak-to-valley surface roughness values ranging from Rx = 10 μm to 200 μm. This approach captures both acceptable and worst-case conditions, aligning with established benchmarks, while avoiding impractically rough scenarios that would over-stress the design. For the analysis, a finite-conductivity boundary, incorporating the built-in Hammerstad–Groiss surface-roughness model, was used in HFSS. The performance results from the analysis are shown in Fig. 6b compare the benchmark acceptable performance with the simulated results under various roughness and dimensional tolerance scenarios. The graph demonstrates that even with these surface roughness conditions and dimensional tolerance changes, such as those shown in Fig. 6a, the waveguide still performs within the acceptable range. Figure 6c illustrates the tolerance analysis, accompanied by a surface roughness scatter heatmap, alongside the simulated surface roughness profiles for each sample. It is noticeable that all higher-order modes are suppressed below − 25 dB, the reflection coefficient remains well below − 15 dB, and the transmission coefficient is above − 0.3 dB.

Figure 7 depicts the field strength evaluated at the location near the coaxial probe, where the likelihood of arcing is highest due to the shorter space. The maximum field strength was found to be 0.29294 kV/cm, which is well within the safe limit for the air breakdown threshold of 30 kV/cm66. The observed value is significantly below the threshold, indicating that the system operates safely without risk of arcing. However, to ensure long-term longevity and reliability, particularly for prolonged space applications, it is recommended to incorporate insulation like Teflon around the connector pin for added protection and enhanced safety.

Material and fabrication method

In this section, a detailed description of the materials used, the overall manufacturing process, and the optimization of 3D printing parameters, along with metallization process details for the 3D-printed coaxial to CWG transition, is presented. For CWG transition sample fabrication, the Creality 3D FFF 3D printer model “K1C” was employed67. The general specifications of the printer are listed in Table 6. A comprehensive list of materials used in the fabrication process of the CWG transition is presented in Table 7. The overall fabrication process, which involves 3D printing the CWG structure, followed by metallization, is illustrated in Fig. 8.

Simulated tolerance and roughness analysis of Ag-coated waveguide transition. (a) S-parameter scatter dimensional-variation. (b) |S11|/|S21| benchmark performance65. (c) S-parameter scatter dimensional + roughness-variation and roughness profile.

Printing waveguides vertically, with flanges at the top, was found to be the optimal orientation during slicing, as it avoids the need for internal support structures and ensures structural integrity. Before printing, the printer undergoes a power-on initialization, which involves calibration, bed leveling, and preset temperatures for both the nozzle and hot bed, configured according to the conductive PLA settings listed in Table 7. Key parameters for optimization trials include layer thickness, infill density, print speed, and nozzle & bed temperatures. For print speed, initial tests conducted at 40 mm/s were too slow, resulting in prolonged heat exposure and overheating of the layers. At 80 mm/s, the layers were insufficiently melted, resulting in weak interlayer adhesion. A balanced speed of 60 mm/s was selected, ensuring proper layer bonding and efficient print timing. Layer thickness was tested between 0.1 mm and 0.3 mm. While 0.1 mm provides superior detail and surface finish, it increases print time; however, 0.3 mm compromises feature detail and surface quality. Therefore, 0.1 mm was selected as the optimal layer thickness due to its precision and consistency. For extrusion temperature, initial tests conducted at 200 °C resulted in poor layer adhesion, while 240 °C caused burning and discoloration of the material. A temperature of 215 °C was chosen for optimal melting and adhesion without overheating. Similarly, the bed temperature was tested across multiple settings, i.e., 30–60 °C, and 50 °C was determined to be the most effective, preventing warping and ensuring good first-layer adhesion. Alternating the raster between + 45° from layer to layer prevents long, uninterrupted shrinkage paths, yielding a smoother surface that plates evenly. Thus, it provides nearly isotropic in-plane stiffness and minimizes warping or curling. The finalized optimal parameters, in addition to those mentioned above, include a linear infill pattern with an infill density of 95% and a default nozzle diameter of 0.4 mm, which were employed to achieve consistent and high-quality 3D prints.

A total of 12 half-waveguide sections, or three back-to-back transitions, were printed. Figure 9 illustrates the 3D-printed CWG transitions, each fabricated with a 0.5 mm wall thickness to ensure structural integrity. After printing, support structures were removed by gradually heating the print bed to 30–40 °C, softening the supports and preventing damage or the rough surface finish often observed when removal is done at room temperature.

In the subsequent post-processing step, printed parts were metallized in three distinct batches, each using a different coating method to isolate its impact on electrical performance. In the first batch, four successive layers of copper spray paint were applied from a fixed distance of 20 cm, with each coat allowed to dry for 60 min before the next application. The second batch received four brush-on layers of silver epoxy paint, similarly cured for one hour between coats. For the third batch, samples were wrapped in two overlapping strips of aluminum foil tape to form a continuous metallic surface. After coating, all painted internal cavities, excluding those covered in aluminum foil, were gently polished using a Yiwu Xinyan LiS42A hand-held drill loaded with buff to achieve a smooth, uniform, shiny finish without altering the geometry. This multi-layered metallization process significantly enhances the electrical conductivity of the PLA substrate’s outer surfaces, improving its suitability for high-performance, low-cost microwave applications.

Results and discussions

The overall CWG transition back-to-back system was tested using an Agilent Technologies E8363 B Vector Network Analyzer (VNA), calibrated to remove the effects of the coaxial cables. The measurement setup is shown in Fig. 10, where two identical transitions are connected back-to-back with two ports of the VNA for the measurement of S-parameters; results are shown in Fig. 11a–c. Three distinct waveguide transition designs with three different coatings (Al, Ag, and Cu) are evaluated, with both simulated and measured results presented across key performance metrics, including return loss, transmission coefficient, and bandwidth. The frequency range of interest for all designs is indicated by the shaded blue region, which spans from 13.4 GHz to 13.75 GHz.

At the operating frequency of 13.6 GHz, the proposed silver-coated waveguide offers the best balance of high transmission and low reflection, providing superior overall performance. This is attributed to its relatively smooth finish, good adhesion, high conductivity, and inherent oxidation resistance. While copper waveguide excels in broadband applications with its broadest − 10 dB bandwidth, it exhibits comparatively higher losses. Aluminium foil waveguide delivers a high-Q reflection coefficient, but its narrower bandwidth limits its wideband applicability. A zoomed-in snippet clarifies the transmission coefficient for the specified frequency. There is a slight deviation in the measured performance of all back-to-back transition designs observed, which does not align perfectly with simulation results. Several factors may contribute to this deviation, including manufacturing tolerances, micro-level surface roughness, non-uniform thickness, seam resistance, and assembly misalignment, all of which can significantly impact impedance matching, mode propagation, ohmic losses, and disturb the surface current distribution. Material limitations, including suboptimal conductivity or higher-than-expected dielectric losses, are common issues. Furthermore, fabrication challenges like microscopic waviness and incomplete contact from hand-wrapped aluminum foil, or imperfections from spray coating handling errors, can significantly compound these effects. Additionally, local air gaps and contact resistance spikes at the flange and pin interfaces can significantly deteriorate electrical continuity, especially when the metallization is thin and porous or applied over anisotropic substrates, such as printed PLA. Another reason for degraded performance in copper and aluminum waveguide samples is their coatings’ increased resistivity from surface oxidation, forming lossy skins of cu₂o and al₂O₃, respectively. Connector mismatches, cable losses, and phase errors in the measurement setup can also introduce additional reflections and distortions, leading to deviated results. VNA calibration drift mismatches at test Ports May further degrade accuracy, but these are second-order effects leading to fractions of decibels of reflection, which can be ignored. While simulations can account for some imperfections, their results often deviate because they typically assume idealized conditions, including perfect material properties, smooth boundaries, and precise Port excitation. Furthermore, the exact levels of real-world imperfections are often unknown, making comprehensive simulation difficult. Performance of each sample can be further improved through subsequent Horn loading, reactive field shaping, the use of vacuum-shrinkable aluminum film with UV-curable adhesive to eliminate wrinkles, and high-quality copper metalization. The overall comparison of simulated results, measurement results, and weight of the back-to-back assembly is listed in Table 8. A single screwless transition weight with a connector in one piece will be silver (Ag, 25.3 g), copper (Cu, 27 g), and aluminum (Al, 26.1 g). In (11) and (12), IL is the insertion loss in decibels. L is the actual wave propagation path length of the 0.2212 dB, while the supplier provided measured connector loss total = 0.155*2 = 0.31 dB and and attenuation ∝ in (dB/m). in. Table 9 summarizes fabrication methods (legacy subtractive machining, SLA, SLS, polyjet, SLM/DMLS, low-cost FFF) and their RF performance. all three FFF prototypes occupy distinct points on the performance–cost plane, offering a cost-effective, easily manufactured alternative to traditional approaches. The use of conductive PLA with copper paint WR-62 design in this study exhibits the highest Attenuation among the other designs presented, with an Attenuation of 9.9 dB/m and a Q-value of 50.83 at 13.68 ghz. This performance surpasses that of other FDM-printed, flange-only conductive PLA counterparts with Attenuation as high as 290 dB/m at 13 ghz, the silver-ink-coated.

ABS (WR-42) variant, which shows 27 dB/m at 22.2 GHz. Some exceptions exist; for example, FDM WR-62, fabricated with a conductive PLA flange only + molten gallium, which achieves an attenuation of 1 dB/m and a Q-value of 1088. However, this comes at the cost of a structurally complex and difficult-to-manufacture design. Another exception copper copper-plated ABS with an attenuation constant of 0.33 dB/m and a Q-value of 174 at ~ 10 GHz. However, it operates at a significantly lower frequency band with larger waveguide dimensions, and it’s relatively easy to manage fabrication accuracies and plating procedures for lower loss characteristics.

On the other hand, the conductive PLA WR-62 design wrapped in aluminum foil exhibits an intermediate attenuation of 3.91 dB/m among the presented variants, yet delivers a substantially higher Q-value of 523.05 at 13.67 GHz. This suggests that it is well-suited for applications that prioritize Q-factor over attenuation, and that foil-wrapped builds can achieve a remarkably high Q without the need for electroplating. Meanwhile, the conductive PLA proposed design coated with silver-epoxy exhibits the lowest attenuation of 0.145 dB/m and a reasonable Q-value of 20.511 at 13.71 GHz. This makes it a viable preferred option for low-power applications where cost and ease of fabrication are priorities. Compared to this, copper-machined WR-90 waveguides have a slightly higher attenuation of 0.3dB/m. In addition, they come at significantly higher costs due to the precision machining process involved.

Other referenced fabrication techniques, such as SLS, DMLS, Polyjet, and SLA, also present alternatives. Among them, SLA methods generally provide superior Q-values due to their inherently smoother surface finish, but they cannot guarantee consistent material properties unless rigorous quality-control measures are applied to the resin curing process. On the other hand, SLM and DMLS stand out in terms of power handling capability due to fine laser printing, and finished products are resilient in harsh environmental conditions. However, relatively rough surfaces can cause performance losses. Polyjet eliminates the handling of metal powder, which is more hazardous than plastic powder. However, the finished products are not as good as those from other methods.

A limitation of the present proof-of-concept study is that it reports only RF performance; long-term reliability, aging phenomena in metallized conductive PLA, and other space-grade testing were not investigated. The prototype is not a flight-ready design and is still undergoing iterations for improved performance. Copper and aluminum surfaces are susceptible to oxidation. Silver epoxy can develop microcracks under thermal cycling, and the polymer substrate itself may creep, thus raising losses. Future work should therefore include aging and thermal exposure, with periodic S-parameter monitoring, coating integrity, and adhesion testing via SEM analysis. These data are essential for determining whether the cost advantages of FFF-printed, post-metallized waveguides can be sustained over time, particularly with flight-qualified, space-grade materials. The results demonstrate that the proposed silver-coated WR-62 waveguides strike a practical balance between performance and cost, leveraging AM and surface coating techniques for rapid customization and scalability. While the other designs, including the copper and aluminum waveguides, do not reach the ultra-low attenuation of the silver-coated variant, they nevertheless offer an innovative and affordable approach for RF and microwave prototyping.

Conclusions and prospects

The proposed study offers a novel hybrid approach to designing CCWG transitions using low-cost, conductive 3D-printed PLA and advanced metallization techniques. The method employs innovative geometrical transformations to minimize EM discontinuities and enhance impedance matching, while an added septum ensures robust linear polarization. The use of FFF with E-plane cut geometry facilitates an easy metallization process, making it a promising alternative to traditional metallic waveguide transitions, which offer lightweight solutions with satisfactory published benchmark performance. The study acknowledges several challenges despite its advantages. Precise and consistent control over surface properties during design and fabrication is critical, as these factors directly impact performance. Additionally, optimizing the printing process is essential to enable scalability for mass production. Furthermore, the long-term durability of these transitions requires further investigation, particularly for applications in harsh environments, such as high-temperature conditions require space-grade material.

Future research could focus on enhancing the electrical conductivity and mechanical properties of 3D-printed structures. Efforts may include developing novel conductive PLA materials with improved conductivity and high-temperature performance. Further research could explore advanced metallization techniques to achieve smoother, more conductive surfaces, including electroplating or atomic layer deposition. Additionally, designing high-temperature metallization coatings could help ensure robust performance under extreme conditions may inspire innovative strategies for high-frequency solutions, etc.

In conclusion, this research applies AM techniques to the design and manufacture of a lightweight, satisfactory-performance waveguide transition prototype. By addressing current challenges and exploring future directions, the study contributes to the development of efficient and sustainable microwave systems for small satellites and space radar applications.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Vaitukaitis, P. Additive manufacturing of novel metal microwave components for space application. PhD diss. Heriot-Watt Univ. (2024). http://hdl.handle.net/10399/5059

Ma, Q. et al. Additive manufacturing of polymer composite millimeter-wave components: recent progress, novel applications, and challenges. Polym. Compos. 46 (1), 14–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.28985 (2025).

Pozar, D. M. Microwave Engineering: Theory and Techniques (Wiley, 2021).

Zhu, Q. C., Williamson, A. G. & Neve, M. J. Design of coaxial line-to-circular waveguide transitions. In 2009 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium Digest, Boston, MA, USA, 265–268. https://doi.org/10.1109/MWSYM.2009.5165684 (2009).

Dey, R., Chakrabarty, S. B. & Jyoti, R. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 55, 2652–2656. https://doi.org/10.1002/mop.27841 (2013).

Mohamadzade, B., Dunning, A., Hayman, D. B. & Smart, K. Broadband coaxial-to-rectangular waveguide transition. In International Conference on Electromagnetics in Advanced Applications (ICEAA), Venice, Italy, 2023, 112–115. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEAA57318.2023.10297906 (2023).

Dansran, B., Xu, S., Heo, J., Lee, C. S. & Ahn, B.-C. Design of a broadband transition from a coaxial cable to a Reduced-Height rectangular waveguide. Appl. Sci. 13(20), 11265. https://doi.org/10.3390/app132011265 (2023).

Pawlan, J. Compact and easy to manufacture dual mode feed horn with ultra-low backlobes. In German Microwave Conference, Nuremberg, Germany, 2015, 355–358. https://doi.org/10.1109/GEMIC.2015.7107826 (2015).

Bang, J. H. & Ahn, B. C. Coaxial-to-circular waveguide transition with broadband mode-free operation. Electron. Lett. 50, 1453–1454. https://doi.org/10.1049/el.2014.2667 (2014).

Altanzaya, E. et al. Computational design of an In-Line Coaxial-to-Circular waveguide adapter WithMore than an octave bandwidth. Symmetry (Basel). 16 (3). https://doi.org/10.3390/sym16030304 (2024).

Guo, C. et al. A 3-D printed E -E-plane waveguide magic-T using air-filled coax-to-waveguide transitions. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Tech. 67 (12), 4984–4994. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMTT.2019.2944355 (2019).

Mediavilla, A., Cano, J. L. & Cepero, K. On the octave bandwidth properties of Octagonal-Shaped waveguide mode Transformers. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Tech. 59 (10), 2447–2451. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMTT.2011.2163077 (2011).

Munir, A. & Musthofa, M. F. Y. Rectangular to circular waveguide converter for microwave devices characterization. Int. J. Electr. Eng. Inf. 3 (3), 350. https://doi.org/10.15676/ijeei.2011.3.3.7 (2011).

Ghazali, M. I. M., Karuppuswami, S., Kaur, A. & Chahal, P. 3-D printed air substrates for the design and fabrication of RF components. In IEEE Transactions on Components, Packaging and Manufacturing Technology, vol. 7, no. 6, pp. 982–989. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCPMT.2017.2686706 (2017).

Byford, J. A., Ghazali, M. I. M., Karuppuswami, S., Wright, B. L. & Chahal, P. Demonstration of RF and microwave passive circuits through 3-D printing and selective metalization. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 7 (3), 463–471. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCPMT.2017.2651645 (2017).

Kim, D. O., Oh, S. M., Lee, J. Y. & Cho, D. H. Surface roughness effects of fabrication technology on metallic waveguide in D-Band for 6G RF communications. In 2023 Photonics & Electromagnetics Research Symposium (PIERS), Prague, Czech Republic, 2205–2208. https://doi.org/10.1109/PIERS59004.2023.10221399 (2023).

Ray Tahir, M. et al. Maximizing performance and efficiency in 3D printing of polylactic acid biomaterials: unveiling of microstructural morphology, and implications of process parameters and modeling of the mechanical strength, surface roughness, print time, and print energy for fused filament fabricated (FFF) bioparts. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 259, 129201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.129201 (2024).

Otter, W. J. & Lucyszyn, S. Hybrid 3-D-printing technology for tunable THz applications. In Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 105, no. 4, 756–767. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2016.2629958 (2017).

Saghlatoon, H., Mirzavand, R., Mousavi, P. & Honari, M. M. Investigation on the effect of roughness of 3D printed structure on performance of microwave devices. In 2018 18th International Symposium on Antenna Technology and Applied Electromagnetics (ANTEM), Waterloo, ON, Canada, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1109/ANTEM.2018.8572974 (2018).

Verploegh, S., Coffey, M., Grossman, E. & Popović, Z. Properties of 50–110-GHz waveguide components fabricated by metal additive manufacturing. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Tech. 65 (12), 5144–5153. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMTT.2017.2771446 (2017).

Diab, R. R., Enzi, A. & Hassoon, O. H. Effect of printing parameters and post-curing on mechanical properties of photopolymer parts fabricated via 3d stereolithography printing. IIUM Eng. J. 24 (2), 225–238. https://doi.org/10.31436/iiumej.v24i2.2778 (2023).

Jasper, S. & Ravichandran, M. Metal fused filament fabrication process—A review. In 2nd International Conference on Smart Sustainable Materials and Technologies (ICSSMT 2023). ICSSMT 2023. Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation. (Springer, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-49826-8_25

Kuhling, J., Dahle, R., Chowdhry, D. & Laforge, P. Applying additive manufacturing to integrate coaxial connectors with 3D printed waveguides for cascaded RF link applications. Addit. Manuf. 35 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2020.101280 (2020).

Filonov, D. et al. Volumetric 3D-Printed antennas, manufactured via selective polymer metallization. Phys. Status Solidi Rapid Res. Lett. 13 (6). https://doi.org/10.1002/pssr.201800668 (2019).

Hofmann, A. et al. SLS-printed E-band waveguides and the impact of surface roughness. In 2023 53rd European Microwave Conference (EuMC), Berlin, Germany, 243–246. https://doi.org/10.23919/EuMC58039.2023.10290537 (2023).

Lucyszyn, S. et al. Polymer-based 3D printed millimeter-wave components for spacecraft payloads. In IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Workshop Series on Advanced Materials and Processes for RF and THz Applications (IMWS-AMP), Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2018, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1109/IMWS-AMP.2018.8457142 (2018).

Laplanche, E. et al. Additive manufacturing of low cost and efficient proof of concepts for microwave passive components. IET Microw. Antennas Propag. 11, 1997–2004. https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-map.2017.0157 (2017).

Nadeem, H., Ghazali, N., Nabeel, M., Ahsan, M. & Khurram, A. Experimental assessment of surface roughness of fused deposition modelling parts and method of improvement. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 37 (3), 1187–1201. https://doi.org/10.1177/08927057231193378 (2024).

Mushtaq, R. T., Iqbal, A., Wang, Y., Khan, A. M. & Abu Bakar, M. S. Parametric optimization of 3D printing process hybridized with laser-polished PETG polymer. Polym. Test. 125, 108129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymertesting.2023.108129 (2023).

Rolando, S., Francisco, P., Dreidy, V. & Eva, R. I. Assessment of 3D-printed waveguides using conductive filaments and a chloroform-based smoothing process. Addit. Manuf. 51, 102593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2022.102593 (2022).

Ghazali, M. I. M., Park, K. Y., Gjokaj, V., Kaur, A. & Chahal, P. 3D printed metalized plastic waveguides for microwave components. Int. Symp. Microelectron. 2017 (1), 000078–000082. https://doi.org/10.4071/isom-2017-TP33_096 (2017).

Dionigi, M., Tomassoni, C., Venanzoni, G. & Sorrentino, R. Simple high-performance metal-plating procedure for stereolithographically 3-D-printed waveguide components. In IEEE Microw. Wirel. Compon. Lett. 27(11), 953–955. https://doi.org/10.1109/LMWC.2017.2750090 (2017).

Falk, M., Lücken, V. & Diewald, A. R. Improvement of a low-cost coaxial-waveguide-transition through coating with aluminum. In 25th International Microwave and Radar Conference (MIKON), Wroclaw, Poland, 2024, 377–381. https://doi.org/10.23919/MIKON60251.2024.10633913 (2024).

Chan, K. Y., Ramer, R. & Sorrentino, R. Low-cost Ku-band waveguide devices using 3-D printing and liquid metal filling. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Tech. 66 (9), 3993–4001. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMTT.2018.2851573 (2018).

Miek, D. et al. Realization of X-band waveguide filters by low-cost FDM additive manufacturing techniques. In German Microwave Conference (GeMiC), Cottbus, Germany, 2020, pp. 208–211 (2020).

Atsushi Ishikawa, T., Kato, N., Takeyasu, K. & Fujimori Kenji tsuruta; selective electroless plating of 3D-printed plastic structures for three-dimensional microwave metamaterials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 30 (18), 183102. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4986203 (2017).

Skaik, T. et al. 3D-Printed dual-mode invar channel filters for Ku-Band satellite payloads. IEEE J. Microwaves. 5 (1), 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1109/JMW.2024.3509956 (2025).

Li, N., Link, G. & Jelonnek, J. Electroplating of 3D printed plastic component for the application of microwave filter. In 2022 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Workshop Series on Advanced Materials and Processes for RF and THz Applications (IMWS-AMP), Guangzhou, China, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1109/IMWS-AMP54652.2022.10106897 (2022).

Deng, J., Burasa, P., Wu, K. & Full-Band, E. Plane waveguide phase shifters with self-compensating characteristics for THz circuits and systems. In 2022 52nd European Microwave Conference (EuMC), Milan, Italy, 2022, 199–202. https://doi.org/10.23919/EuMC54642.2022.9924360.

Kim, I., Kovitz, J. M. & Rahmat-Samii, Y. Enhancing the power capabilities of the stepped septum using an optimized smooth sigmoid profile. IEEE Antennas Propag. Mag. 56 (5), 16–42. https://doi.org/10.1109/MAP.2014.6971913 (2014).

Massa, G. et al. 3D Printed Materials Characterization for Rapid Prototyping and Plant Growth (2024).

Chen, Z. & Zosimovych, N. Mission capability assessment of 3D printing Cubesats. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 012025. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/608/1/012025 (IOP Publishing, 2019).

He, Y. & Damas, C. A raspberry pi powered 1U CubeSat (2021). https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5157&context=smallsat (accessed 23 Jun 2025).

Roberts, K. A. Design and Testing of an additively manufactured CubeSat Structural Bus. (2018). https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD1056620 (accessed 23 Jun 2025).

Robey, D. L. Development, integration, and evaluation of lightweight materials for cubesat architectures. (2021). https://calhoun.nps.edu/bitstream/handle/10945/68740/21Dec_Robey_Daniel.pdf (accessed 04 Jun 2025).

Pittella, E., D’Alvia, L. & Piuzzi, E. CubeSat satellite patch antenna designed with 3D printable materials: a numerical analysis. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2526 (1), 012042. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/2526/1/012042 (2023).

Aguilar, D., Christensen, S. & Fox, E. J. 3-D printed Ultem 9085 testing and analysis. In ISS R&D Conf.. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20150017060/downloads/20150017060.pdf (2015).

Space’s, T. A. 3D printed part in space: mission successful. (2025). https://www.thalesgroup.com/en/worldwide/space/news/3d-printed-part-space-mission-successful# (accessed 04 Jun).

Pradhan, E., Dadheech, A., Agarwal, H., Singh, T. & Singari, R. M. Design concept of a model can-sized sub-orbital satellite. J. Engg Res. EMSME Special Issue. 79, 88. https://doi.org/10.36909/jer.EMSME.13883 (2021).

Carkaci, M. E. & Secmen, M. Design and prototype manufacturing of a feed system for Ku-band satellite communication by using 3D FDM/PLA printing and conductive paint technology. Int. J. RF Microw. Comput.‐Aided Eng. 30 (4), e22062. https://doi.org/10.1002/mmce.22062 (2020).

Space, N. A. National aeronautics and space administration. Retrieved Natl. Aeronaut. Space Administration: www Nasa Gov (1977).

Why & ULTEM 1010 Is the New Standard for 3D Printed Satellite Components. https://media.visionminer.com/why-ultem-1010-is-the-new-standard-for-3d-printed-satellite-components/ (accessed 04 Jun 2025).

Paek, S. W., Balasubramanian, S. & Stupples, D. Composites additive manufacturing for space applications: A review. Materials. 15 (13). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15134709 (2022).

Plante, J. & Lee, B. Environmental conditions for space flight hardware: A survey. (2005). https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20060013394 (accessed 04 Jun 2025).

Robert, P. et al. Thales SESO silver coatings for space programs. In Proc. SPIE,118524 M. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2599795 (2021).

O. C. Quality Management System. Burlington, 842AR Liquid SUPER SHIELD™ Silver Conductive Paint. https://mgchemicals.com/downloads/tds/tds-842ar-l.pdf (accessed 04 Jun 2025).

Goldberg, D. A., Laslett, L. J. & Rimmer, R. A. Comparison of Methods for Determining Eigenmodes of Elliptical Waveguides. (1990). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9ds841tm.

Zhang, S. & Shen, Y. Eigenmode sequence for an elliptical waveguide with arbitrary ellipticity. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 43 (1), 227–230. https://doi.org/10.1109/22.362983 (1995).

Chu, L. J. Electromagnetic waves in elliptic Hollow pipes of metal. J. Appl. Phys. 9 (9), 583–591. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1710459 (1938).

Hokua, R. F. & GmbH Elliptical Waveguide. https://hokua-rf.com/designtools/transmission-line-calculator/elliptical-waveguide/ (accessed 12 Jun 2025).

Tamayo-Dominguez, A., Fernandez-Gonzalez, J. M. & Sierra-Perez, M. Metal-coated 3D-printed waveguide devices for mm-wave applications. IEEE Microw. Mag. 20 (9), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1109/MMM.2019.2922121 (2019).

Michael, M. & Paint, E. C. Where to buy it, and how to make it–the ultimate guide. https://www.hobbyistgeek.com/electroforming-conductive-paint-how-to-make/ (accessed 02 Jun 2025).

Callister, W. D. & Rethwisch, D. G. Materials Science and Engineering: An Introduction (Wiley, 2020). https://books.google.co.id/books?id=dmoTEQAAQBAJ

Xometry Tolerances in 3D printing. https://xometry.pro/en-eu/articles/3d-printing-tolerances/ (accessed 02 Jun 2025).

Burtsev, V. D. et al. Comprehensive analysis of surface roughness for extremely high frequency antennas. Photon. Nanostruct. 63 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.photonics.2024.101345 (2025).

Microwave, D. 6 Specific aspects of arcing in waveguides. https://www.dolphmicrowave.com/default/6-specific-aspects-of-arcing-in-waveguides/ (accessed 02 Jun 2025).

Creality, K. C. & Printer Website Creality. https://www.creality3dofficial.com/products/creality-3d-printer-online-store-k1c-3d-printer (accessed 02 Jun 2025).

D’Auria, M. et al. 3-D printed metal-pipe rectangular waveguides. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 5 (9), 1339–1349. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCPMT.2015.2462130 (2015).

Khan, S., Vahabisani, N. & Daneshmand, M. A fully 3-D printed waveguide and its application as microfluidically controlled waveguide switch. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 7 (1), 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCPMT.2016.2631545 (2017).

Márquez-Segura, E., Shin, S. H., Dawood, A., Ridler, N. M. & Lucyszyn, S. Microwave characterization of conductive PLA and its application to a 12 to 18 ghz 3-D printed rotary Vane attenuator. IEEE Access. 9, 84327–84343. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3087012 (2021).

Youssef, C. et al. Ku-band lightweight aluminium waveguides fabricated by direct metal laser sintering process. In 2020 International Symposium on Advanced Electrical and Communication Technologies (ISAECT), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISAECT50560.2020.9523695 (2020).

Booth, P. & Lluch, E. V. Enhancing the performance of waveguide filters using additive manufacturing. Proc. IEEE. 105(4), 613–619. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2016.2616494 (2017).

Chen, Y. et al. 3-D printed dual-band filter based on spherical dual-mode cavity. IEEE Microwave Wirel. Compon. Lett. 31 (9), 1047–1050. https://doi.org/10.1109/LMWC.2021.3080430 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge with thanks the support of King Abdulaziz University to this study. The authors would also like to acknowledge with thanks the support of International Science and Technology Cooperation, National Natural Science Foundation of China and Northwestern Polytechnical University China to this study.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge with thanks the support of King Abdulaziz University to this study. This work was supported by International Science and Technology Cooperation Project of Ningbo Key R&D Program[2024H031] and National Natural Science Foundation of China [62073261].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.M.F.: Conceptualization, software, methodology, validation, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, data curation; H.H.: Project administration, funding acquisition, supervision, resources, writing—review and editing; R.T.M.: Methodology, investigation, writing—review and editing; K.A.A.: Formal analysis, review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent is not required for this study as it involves no human participation or interaction.

Consent to publish

All authors have read and approved this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fahad, H.M., Huang, H., Mushtaq, R.T. et al. Additively manufactured lightweight coaxial to circular waveguide transition for linearly polarized microwave systems. Sci Rep 15, 27185 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11467-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11467-z