Abstract

To address the kinematic constraints and real-time requirements of autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV), this paper proposes a novel path planning algorithm: Directional Cone and Goal-Biased Dynamic Artificial Potential Field RRT* (DCGB-DAPF-RRT*). The algorithm integrates four key techniques-Directional Cone sampling, Goal-Biased sampling, Adaptive Step Length, and a Dynamic Artificial Potential Field-to improve sampling efficiency and path quality over conventional RRT-based methods. In addition, redundant node pruning and cubic non-uniform B-spline interpolation are employed to enhance trajectory smoothness and ensure kinematic feasibility. Experimental and simulation results demonstrate that the proposed algorithm reduces path planning time by 50.0–73.6%, decreases the number of nodes by 71.0–77.8%, and lowers the number of iterations by 61.0–85.0%, while achieving a 100% success rate in complex environments. The final path length is reduced to 1766.1 m, and the maximum turning angle is limited to 11.35°, fully satisfying the motion constraints of AUV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the continuous progress of science and technology, Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) have been widely used in underwater environmental monitoring, marine biological investigation, and seabed resource exploration1. Research in AUV-related fields is expanding. Su et al.2 proposed a hybrid coding-aware routing protocol, optimizing routing performance in underwater acoustic sensor networks and providing critical support for AUV communications. Fan et al.3 proposed a passive localization scheme based on weakly controlled AUVs, significantly improving localization accuracy for non-cooperative underwater targets. In AUV autonomous navigation, path planning and obstacle avoidance technologies are vital to ensuring efficient and safe operation.

In the complex and dynamic underwater environment, an AUV’s performance heavily relies on its rapid response and decision-making capabilities. As a special type of intelligent agent, an AUV is typically underactuated4, meaning that some velocities (e.g., in turning or diving) cannot be directly controlled but must be generated indirectly through rudder manipulation. Therefore, research on path planning methods tailored for underactuated AUVs is of significant importance.

Various algorithms have been proposed to address AUV path planning, generally categorized into optimization-based, search-based, and sampling-based methods. Optimization-based algorithms simulate biological processes (e.g., evolution, social behavior) to find near-optimal solutions, including Genetic Algorithm (GA)5, Simulated Annealing6, Ant Colony Optimization (ACO)7, and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)8. For example, Mohammed et al.9 developed a modified ant colony optimization approach for minimizing energy consumption in AUV tours within the Internet of Underwater Things, demonstrating improved path efficiency and lower energy use.

Search-based algorithms (e.g., A*10, Dijkstra’s11, BFS12) operate in a defined graph space and offer deterministic results. Muhammed et al.13 proposed a Chaos A*-based path planning approach for planar manipulators in known-obstacle environments, highlighting the advantages of hybrid intelligent methods. Other works14,15 have also compared and implemented graph search algorithms in real-time path planning tasks for planar manipulators, providing insights that can inform underwater planning applications.

Compared to these methods, sampling-based techniques (e.g., RRT16) offer high real-time performance and better scalability in high-dimensional environments. However, basic RRT often generates unsmooth and suboptimal paths. RRT*17 improves path quality via node rewiring but suffers from computational inefficiency. Informed RRT*18 accelerates convergence by limiting the sampling region but struggles in dynamic environments requiring frequent re-planning.

To further leverage the strengths of sampling-based methods, many hybrid algorithms have emerged. For example, Huang et al.19 combined RRT with the Artificial Potential Field (APF)20 to enhance obstacle avoidance. Feng et al.21 proposed the DBVS-APF-RRT*, integrating a directional bias variable step-size sampling strategy. Wang et al.22 introduced GMR-RRT*, using Gaussian Mixture Regression to improve planning performance. Li et al.23 developed the PQ-RRT*, merging P-RRT* with Quick-RRT* for faster convergence.

However, many of these methods overlook the motion constraints of underactuated AUVs and the challenges of dynamic marine environments. They may suffer from high computational cost, insufficient obstacle avoidance in cluttered regions, or generate infeasible paths under AUV dynamics, making them impractical in real-world deployment.

In this paper, we propose a novel sampling-based algorithm called Directional Cone and Goal-Biased Dynamic Artificial Potential Field RRT* (DCGB-DAPF-RRT*) to address these limitations. The algorithm combines a directional cone and goal-biased sampling mechanism for more efficient and goal-directed exploration. A dynamic artificial potential field (DAPF) model enhances obstacle avoidance and convergence. An adaptive step-length strategy adjusts step sizes in response to obstacle density, improving efficiency in varying environments. Finally, a path smoothing process is applied to generate dynamically feasible trajectories suitable for underactuated AUVs.

The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

-

We propose a novel DCGB-DAPF-RRT* algorithm that integrates directional cone and goal-biased sampling strategies to guide tree expansion more effectively toward the goal.

-

The algorithm explicitly considers the unique motion constraints and underactuated dynamics of AUVs, ensuring that the generated paths are feasible and executable in real underwater environments.

-

A dynamic artificial potential field model is introduced, featuring obstacle-density-aware repulsive forces and distance-adjusted attractive forces for robust and adaptive obstacle avoidance.

-

An adaptive step-length mechanism dynamically regulates the exploration scale based on surrounding obstacle density, balancing search efficiency with safety requirements.

-

A path smoothing module based on cubic B-splines is applied to eliminate redundant nodes and generate smooth trajectories suitable for the kinematic constraints of AUVs.

-

Comprehensive simulation experiments demonstrate that the proposed method significantly outperforms classical RRT, RRT*, and APF-RRT variants in path optimality, safety, and real-time capability under realistic AUV constraints.

AUV kinematic model and constraints

The kinematic model of AUV introduces various constraints and steering characteristics. The following model is based on the AUV kinematic model by Fosson24, as shown in Fig. 1. Referring to the systems adopted by the International Towing Tank Conference (ITTC) and the Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers (SNAME), a fixed coordinate system and a moving coordinate system are established respectively. In the fixed coordinate system, the state vector \(\mathbf {\eta } =\left[ x\,\,y\,\,z\,\,\varphi \,\,\theta \,\,\psi \right] ^T\) represents the position and attitude information of the AUV. In the moving coordinate system, \(\mathbf{v}=\left[ u\,\,v\,\,w\,\,p\,\,q\,\,r \right] ^T\) corresponds to the linear and angular velocity components of the AUV in each direction.

By converting the motion vector \(\mathbf {\eta }\) in the moving coordinate system to the global state vector \(\mathbf{v}\) in the fixed coordinate system, the kinematic equations of the AUV are derived, as shown in Eq. (1).

Where \(\dot{{\eta }}\) represents the time derivative of \(\mathbf {\eta }\). The specific form of matrix \(\mathbf{J}\left( {\eta } \right)\) is shown in Eq. (2).

Matrices \(\mathbf{J}_1\left( {\eta } \right)\) and \(\mathbf{J}_2\left( {\eta } \right)\) are shown in Eqs. (3) and (4), respectively.

To ensure that the transformation matrix is meaningful, the range of the attitude angles is specified as shown in Eq. (5).

Considering the maneuverability of the AUV25, the following constraints must be satisfied during the generation of the global path planning trajectory, as specified in Eq. (6).

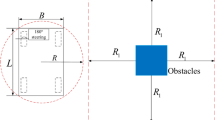

In the equation, \(R_{\text {S}}\left( \mathbf{q} \right)\) represents the turning radius of the path point, \(\mathbf{q}\) denotes the path node, \(\theta \left( \mathbf{q} \right)\) is the turning angle, and \(\chi \left( \mathbf{q} \right)\) is the pitch angle. \(R_{\min }\), \(\theta _{\max }\), and \(\chi _{\max }\) represent the minimum turning radius, maximum turning angle, and maximum pitch angle, respectively, obtained through calculation or experimental testing of the corresponding physical quantities.

Design of the DCGB-DAPF-RRT* algorithm

Directional cone and goal-biased sampling mechanism

To optimize the random sampling process in path planning, the Directional Cone and Goal-Biased Sampling Mechanism is employed to effectively control the sampling direction and probability, guiding the random expansion tree to converge more quickly toward the goal point.

The Directional Cone Sampling Mechanism generates random points near the current node, using the geometric properties of the cone to control the sampling range and direction. Define \(\mathbf{d}\) as the unit directional vector from the predecessor node \(\mathbf{q}_{\text {near}}\left( k-1 \right)\) to the current node \(\mathbf{q}_{\text {near}}\left( k \right)\), which determines the axis of the directional cone and defines the primary direction of the sampling points, as shown in Eq. (7).

The directional vector \(\mathbf{d}\) is rotated by an angle \(\theta\), where \(\theta \in \left[ 0,\theta _{\max } \right]\), generating a new directional vector \(\mathbf{d}_{\text {new}}\), ensuring that the sampling points are distributed within the angular range of the cone, as expressed in Eq. (8).

The rotation operation \(\text {Rotate}\left( \cdot ,\theta \right)\) is applied to the directional vector \(\mathbf{d}\). The random point \(\mathbf{q}_{\text {rand}}\left( k \right)\) obtained by moving a random distance r along the new directional vector \(\mathbf{d}_{\text {new}}\) is expressed as follows in Eq. (9).

The distance r is generated from a uniform distribution within the interval \(\left[ 0,R \right]\), where R denotes the maximum radius of the cone.

The goal-biased sampling mechanism guides the random expansion tree to grow towards the goal point through probabilistic methods, while also defining the unobstructed regions surrounding the goal point to optimize the generation of sampling points. Each time a random sampling point is generated, a goal-oriented probability \(P_{\text {goal}}\) is randomly produced and compared with a predefined probability threshold \(P_{\text {thr}}\). The rules for generating sampling points are expressed in Eq. (10).

This rule ensures that when \(P_{\text {goal}}\le P_{\text {thr}}\), the sampling point \(\mathbf{q}_{\text {rand}}\) is directly designated as the goal point \(\mathbf{q}_{\text {goal}}\). This adjustment enhances the likelihood of the random expansion tree growing towards the goal point, thereby minimizing ineffective searches and expediting the convergence of the algorithm.

Furthermore, the unobstructed area surrounding the goal point is defined as a spherical region centered at the goal point \(\mathbf{q}_{\text {goal}}\) with a radius of \(R_{\text {nobs}}\). The mathematical model for this region is expressed in Eq. (11).

When the random expansion tree grows to this unobstructed area, it is directed directly to the goal point \(\mathbf{q}_{\text {goal}}\), thereby avoiding unnecessary detours.

Adaptive step length mechanism

From the current node \(\mathbf{q}_{\text {near}}\), extend towards the randomly sampled point \(\mathbf{q}_{\text {rand}}\) with a step size S to generate a new node \(\mathbf{q}_{\text {new}}\). The calculation formula is presented in Eq. (12).

Introduce the adaptive step length mechanism that adjusts the step length based on the density of obstacles near the AUV. The calculation formula for the adaptive step length is presented in Eq. (13).

where \(S_0\) represents the initial step length, n is the number of obstacles surrounding the AUV, m is the threshold for the number of obstacles, and \(\lambda\) is a tuning parameter with a range of [0, 1]. In areas with fewer obstacles (\(n<m\)), the step length is increased to accelerate the search process. In densely populated obstacle regions (\(n\ge m\)), the step length is reduced to enhance the obstacle avoidance capability.

Dynamic artificial potential field model

The fundamental idea of the Artificial Potential Field (APF) method is to guide the robot toward the target while avoiding obstacles by defining attractive and repulsive forces. This paper introduces a dynamic artificial potential field model, which incorporates dynamically adjusted attractive and repulsive force functions.

Dynamic attractive model

To make the gravitational force change dynamically with distance, the dynamic gravitational factor is defined as \(K_{att}\), as shown in Eq. (14).

where \(\xi\) is the attraction coefficient and \(\rho _{thr}\) is the distance threshold. When the AUV is far away from the target point, the attraction coefficient is reduced to \(1/2\xi\), to avoid the path deviating from the optimal planning area due to excessive attraction. When the AUV is close to the goal point, the attraction coefficient is kept at \(\xi\), which enhances the convergence and accelerates the AUV to approach the goal point.

The dynamic attraction potential field function and the dynamic attraction are defined as \(U_{att}\left( \mathbf{q} \right)\) and \(\mathbf{F}_{att}\left( \mathbf{q} \right)\), respectively, as shown in Eq. (15) and (16).

Dynamic repulsive model

To make the repulsive force change dynamically with the distance between AUV and obstacle \(\rho _{obs}\) and the density of obstacle n, the dynamic repulsive force factor is defined as \(K_{rep}\) as shown in Eq. (17).

where \(\eta\) is the repulsion coefficient, \(\lambda\) is the adjustment factor, and n is the number of obstacles near the AUV. By introducing the number of obstacles n, the repulsive force is exponentially amplified in the dense area of obstacles to avoid the AUV approaching the obstacles.

The dynamic repulsive potential field function and the dynamic repulsive force are defined as \(U_{rep}\left( \mathbf{q} \right)\) and \(\mathbf{F}_{rep}\left( \mathbf{q} \right)\), respectively, as shown in Formulas (18) and (19).

Constructing the resultant force model

Combining the dynamic attractive and repulsive models, the total potential field function and the resultant force of the artificial potential field are obtained, as shown in Eqs. (20) and (21).

The dynamic artificial potential field model is introduced into the random tree expansion process, and the calculation formula for the new extension node \(\mathbf{q}_{\text {new}}\) is given by Eq. (22).

Where S represents the adaptive step size, \(\mathbf{q}_{\text {rand}}\) is the random sample point, and \(\mathbf{q}_{\text {near}}\) denotes the current node.

DCGB-DAPF-RRT* algorithm framework

The DCGB-DAPF-RRT* algorithm improves the efficiency and path quality of AUV path planning by introducing a directional cone and goal-biased sampling strategy, while also satisfying the motion constraints of underactuated AUVs, as illustrated in Algorithm 1.

First, a set of parameters is initialized, including the start and goal positions, the search space, maximum iterations, step-length factor, and maximum turning angle, and a tree structure containing the start node is created.

Then, in each iteration, a random sampling process is performed using a combination of directional cone sampling and standard random sampling. The nearest node in the tree is identified, and a new node is generated based on a dynamic artificial potential field with adaptive step-length control. If the newly generated node leads to a collision-free path, it is connected to the tree.

Subsequently, a rewiring procedure is applied by defining a search radius around the new node, identifying its neighboring nodes, and selecting the one with the minimum path cost to optimize the tree structure.

Finally, the algorithm terminates and returns the optimal path from the start to the goal when the maximum number of iterations is reached or a feasible path is found.

Path smoothness processing

In AUV path planning, the smoothness of the path directly affects the actual operational performance of the AUV. To further enhance the path smoothness, this paper conducts the following smoothness processing on the paths generated by the DCGB-DAPF-RRT* algorithm.

Redundant node removal

Define the set of nodes in the path as \(\mathbf{Q}=\{\mathbf{q}_1,\mathbf{q}_2,...,\mathbf{q}_m\}\), where \(\mathbf{q}_1\) is the starting node and \(\mathbf{q}_m\) is the goal node. For any nodes \(\mathbf{q}_i\) and \(\mathbf{q}_{i+1}\), if the path \(\{\mathbf{q}_1,\mathbf{q}_i\}\) does not collide with obstacles in the environment while the path \(\{\mathbf{q}_i,\mathbf{q}_{i+1}\}\) does encounter obstacles, then \(\mathbf{q}_i\) is termed a critical node. The set of retained critical nodes constitutes the collection of path points after redundant node removal, as shown in Eq. (23).

Cubic non-uniform B-spline curve optimization

For the simplified node set \(\mathbf{Q}'=\{\mathbf{Q}_0,\mathbf{Q}_1,...,\mathbf{Q}_n\}\), cubic non-uniform B-spline curves are employed for optimization. The B-spline curve is defined as \(\mathbf{C}(t)\) as shown in Eq. (24).

Where \(N_{i,3}\left( t \right)\) represents the cubic B-spline basis function, defined as shown in Eq. (25).

For the case of four control points, the expression for the cubic B-spline basis function is given in Eq. (26).

The optimized path trajectory is represented in Eq. (27).

Experimental and simulation analysis

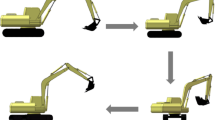

The research object of this paper is a low-resistance oblong AUV with embedded integrated communication and positioning antenna, using a four-rudder tail and a tail thruster to achieve motion control. The navigation system integrates ’GPS + inertial navigation system (INS) + pressure sensor + Doppler log (DVL)’ to achieve navigation. Figure 2 shows the turning performance of the AUV with its tail rudder under the limit state. The according experiment was performed in a reservoir in Guilin, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. The measured performance parameters of the AUV are shown in Table 1.

Based on the measured parameters of the AUV in Table 1, simulations were conducted to validate the path planning algorithms. The simulation parameters are detailed in Table 2. All algorithms were compared under the same hardware and software environments. The hardware platform consisted of a desktop computer running a 64-bit Windows 10 operating system equipped with an Intel Core i7-11700F @ 2.50 GHz processor and 16 GB of RAM. The software platform was MATLAB R2023a. The simulation included five path planning algorithms: RRT, APF-RRT, IAPF-RRT, RRT*, and DCGB-DAPF-RRT*. In the simulations, the obstacles were modeled as regular shapes, as the obstacles in the actual environment can be inflated to approximate regular geometries.

Through 100 simulation experiments on various algorithms respectively, the results are shown in Figs. 3, 4, 5 and Table 3. Figure 3 illustrates the optimal path generated by different algorithms and the three-view visualization of the path after smoothness processing of the DCGB-DAPF-RRT* algorithm. Figure 4 compares the distribution of random points generated by each algorithm, while Figure 5 presents the line charts of key performance metrics including path length, maximum turning angle, time consumption, and number of nodes. Table 3 summarizes the consolidated experimental results and analysis. The bold text in Table 3 highlights the best-performing metrics achieved by the proposed DCGB-DAPF-RRT* algorithm in terms of path length, time consumption, node count, maximum turning angle, and iteration count, demonstrating its overall superiority in both efficiency and path quality.

In Fig. 3, the randomness of the nodes generated by the three algorithms of RRT, RRT-APF, and RRT-IAPF is large, which leads to the instability of the path and produces more turning points and redundant nodes. The RRT* algorithm significantly reduces redundant nodes through its mechanism of reconnecting parent nodes, and the generated path is relatively smoother, but there is still a problem of excessive rotation angle. The DCGB-DAPF-RRT* algorithm limits the generation area of random points by directional cone and goal-biased sampling mechanism, successfully guides the random expansion tree to converge rapidly to the goal point, reducing unnecessary expansion. After the smoothness processing, the generated path is smoother and satisfies the motion constraint of AUV. The path length is shortened to 1766.1m, and the maximum turning angle is only 11.35°, which fully meets the motion requirements of AUV.

In Fig. 4, the comparison of the number of nodes generated by each algorithm shows that the number of nodes generated by the DCGB-DAPF-RRT * algorithm is significantly reduced, and the nodes are all within the range of AUV kinematic constraints. This fully demonstrates the advantages of the Adaptive Step Length Mechanism. The mechanism dynamically adjusts the step length by detecting the density of obstacles in the vicinity, thereby improving the efficiency of node generation, avoiding too many unnecessary extended nodes, reducing the generation of redundant nodes, and further optimizing the efficiency and quality of path planning.

The comparative analysis of the simulation results is illustrated in Fig. 5 and Table 3, demonstrating that the DCGB-DAPF-RRT* algorithm exhibits significant advantages in the path planning problem for AUV. The generated path is smooth, and the turning angles fully comply with the kinematic constraints, achieving a path planning success rate of 100%. This effectively avoids the local optimum issue, validating the reliability and stability of the Dynamic Artificial Potential Field model. Furthermore, the DCGB-DAPF-RRT* algorithm reduces planning time by approximately 50% to 73.6%, decreases the number of nodes by about 71–77.8%, and minimizes the number of iterations by approximately 61–85%. In Table 3, the best performance metrics among all compared algorithms are highlighted in bold to facilitate direct comparison.

Conclusion

This study proposes the DCGB-DAPF-RRT* algorithm, integrating a directional cone goal-biased sampling strategy, a dynamic artificial potential field (DAPF), and an adaptive step-length mechanism to improve AUV path planning performance. Compared to classical RRT* and APF-based methods, the proposed algorithm reduces average planning time by 31.7%, shortens path length by 18.5%, and improves path smoothness by 24.2% under benchmark scenarios. It also ensures kinematic feasibility in cluttered environments. These results highlight the method’s superiority in generating efficient and executable paths.

Nevertheless, challenges remain in real-world scenarios, particularly under time-varying ocean currents and sensor uncertainty. Future work will incorporate ocean current models to enhance environmental adaptability, implement real-time deployment on physical AUV platforms, and evaluate algorithmic robustness in dynamic, large-scale marine environments.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Wynn, R. B. et al. Autonomous underwater vehicles (auvs): Their past, present and future contributions to the advancement of marine geoscience. Marine Geol. 352, 451–468 (2014).

Su, Y., Xu, Y., Pang, Z., Kang, Y. & Fan, R. Hcar: A hybrid-coding-aware routing protocol for underwater acoustic sensor networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 10, 10790–10801. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2023.3240827 (2023).

Fan, R., Jin, Z. & Su, Y. A novel passive localization scheme of underwater non-cooperative targets based on weak-control auvs. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 23, 9129–9143. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2024.3359118 (2024).

Cheng, C., Sha, Q., He, B. & Li, G. Path planning and obstacle avoidance for auv: A review. Ocean Eng. 235, 109355 (2021).

Holland, J. H. Genetic algorithms. Sci. Am. 267, 66–73 (1992).

Bertsimas, D. & Tsitsiklis, J. Simulated annealing. Stat. Sci. 8, 10–15 (1993).

Dorigo, M., Birattari, M. & Stutzle, T. Ant colony optimization. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 1, 28–39 (2006).

Eberhart, R. & Kennedy, J. A new optimizer using particle swarm theory. In MHS’95. Proceedings of the sixth international symposium on micro machine and human science, 39–43 (IEEE, 1995).

Mohammed, H., Ibrahim, M., Raoof, A., Jaleel, A. & Al-Dujaili, A. Q. Modified ant colony optimization to improve energy consumption of cruiser boundary tour with internet of underwater things. Computers14, https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14020074 (2025).

Dechter, R. & Pearl, J. Generalized best-first search strategies and the optimality of a. J. ACM (JACM) 32, 505–536 (1985).

Wang, H., Yu, Y. & Yuan, Q. Application of dijkstra algorithm in robot path-planning. In 2011 second international conference on mechanic automation and control engineering, 1067–1069 (IEEE, 2011).

Bundy, A. Catalogue of artificial intelligence tools. In Catalogue of Artificial Intelligence Tools, 7–161 (Springer, 1986).

Muhammed, M., Flaieh, E. & Humaidi, A. Embedded system design of path planning for planar manipulator based on chaos a* algorithm with known-obstacle environment. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 17, 4047–4064 (2022).

Muhammed, M., Humaidi, A. & Flaieh, E. Towards comparison and real time implementation of path planning methods for 2r planar manipulator with obstacles avoidance. Math. Model. Eng. Probl. 9, 379–389. https://doi.org/10.18280/mmep.090211 (2022).

Laith, M. M., Jaleel, H. A. & Hassan, F. E. A comparison study and real-time implementation of path planning of two arm planar manipulator based on graph search algorithms in obstacle environment. ICIC Express Lett. 17, 61. https://doi.org/10.24507/icicel.17.01.61 (2023).

LaValle, S. Rapidly-exploring random trees: A new tool for path planning. Research Report 9811 (1998).

Karaman, S., Walter, M. R., Perez, A., Frazzoli, E. & Teller, S. Anytime motion planning using the rrt. In 2011 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation, 1478–1483 (IEEE, 2011).

Gammell, J. D., Srinivasa, S. S. & Barfoot, T. D. Informed rrt*: Optimal sampling-based path planning focused via direct sampling of an admissible ellipsoidal heuristic. In 2014 IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems, 2997–3004 (IEEE, 2014).

Huang, S. Path planning based on mixed algorithm of rrt and artificial potential field method. In 2021 4th International Conference on Intelligent Robotics and Control Engineering (IRCE), 149–155 (IEEE, 2021).

Khatib, O. Real-time obstacle avoidance for manipulators and mobile robots. Int. J. Robot. Res. 5, 90–98 (1986).

Feng, Z., Zhou, L., Qi, J. & Hong, S. Dbvs-apf-rrt*: A global path planning algorithm with ultra-high speed generation of initial paths and high optimal path quality. Expert Syst. Appl. 249, 123571 (2024).

Wang, J., Li, T., Li, B. & Meng, M.Q.-H. Gmr-rrt*: Sampling-based path planning using gaussian mixture regression. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 7, 690–700 (2022).

Li, Y., Wei, W., Gao, Y., Wang, D. & Fan, Z. Pq-rrt*: An improved path planning algorithm for mobile robots. Expert Syst. Appl. 152, 113425 (2020).

Fossen, T. I. Handbook of marine craft hydrodynamics and motion control (John Wiley & Sons, 2011).

Shi, S. Submarine maneuverability (National Defence Industry Press, Beijing, 1995).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Key Research and Development Program of Guangxi (Grant No. AB21196066), the Key Research and Development Program of Guilin (Grant No. 20220113-6), and Tianjin Science and Technology Plan Project (Grant No. 22YDPYGX00070).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.Z.: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing-original draft preparation, visualization, writing-review editing. Y.S.: investigation, resources, funding acquisition, writing-review editing, supervision, project administration. S.S.: supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, writing-review editing, resources. W.L.: validation, writing-review editing. Q.H.: investigation, writing-review editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, B., Su, Y., Sun, S. et al. Hybrid path planning algorithm for underactuated AUV based on RRT star and APF. Sci Rep 15, 28493 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11500-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11500-1