Abstract

Medical devices that come in direct contact with human skin or the oral cavity will inevitably be contaminated with microorganisms, including potential pathogens. Ensuring the microbiological safety of such devices is therefore crucial to prevent infections. Healthcare institutions usually have the facilities needed for effective sterilization of reusable medical devices. However, effective sterilization or disinfection of medical devices for usage at home has remained challenging both in terms of pathogen elimination and user safety. Preferably, this involves easy-to-operate equipment that works at relatively low temperatures and atmospheric pressure. In principle this need can be met by disinfection with steam. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to examine the efficacy of a simple electronic steam machine designed for home usage. Our results show that exposure to steam at 100 °C for 60 s resulted in complete eradication (100% reduction) of bacterial contaminants, including Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Significant bacterial reductions (ranging from ~ 90–100%) were also observed within shorter exposure times (10–30 s), depending on the strain. Importantly, the applied steam disinfection approach is effective even against biofilm-embedded bacteria, or bacteria applied to a medical device for home usage, as exemplified with a nebulizer that is used by patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). In conclusion, our results provide quantitative proof-of-concept evidence that portable steam-generating devices that operate at atmospheric pressure can be used for effective disinfection of reusable medical devices in home settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medical devices that come in direct contact with patients must be sterilized or disinfected to prevent their contamination, colonization or infection by pathogenic microorganisms1. As proposed by Spaulding, sterilization is required for reusable critical items that enter sterile tissue or the vascular system, high-level disinfection is required for reusable semi-critical items that contact mucous membranes or non-intact skin, and decontamination is required for non-critical items that come in contact with intact skin, but not the mucous membranes2,3. Effective sterilization will result in the complete elimination or destruction of all forms of microbial life, including spores4. In healthcare facilities this is achieved either by physical or chemical means. The physical means of sterilization include heating at high pressure or exposure to ultraviolet light or ionizing irradiation. Chemical device sterilization involves exposure to gases, such as ethylene oxide (Eto), nitrogen dioxide or ozone, or exposure to liquids, such as formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde, hydrogen peroxide or peracetic acid5,6. However, these methods are often associated with significant limitations, including high cost, operational complexity, toxicity risks, and incompatibility with heat-sensitive materials7,8. Of the latter, formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde are nowadays less frequently used because of their toxicity. The method of choice depends largely on the properties of the medical device that needs to be sterilized or disinfected, the available equipment for sterilization/disinfection and the infrastructure required to apply the different approaches. Importantly, many of these approaches are not suitable for use outside healthcare facilities, because they necessitate the use of sealed containers, are costly, complex in use, and/or not suitable for handling by non-professional users9. This presents a substantial barrier to safe and effective disinfection of reusable medical devices in home settings, where access to such infrastructure is lacking10.

Steam sterilization, also referred to as moist-heat sterilization, is widely employed to achieve sterilization of devices as an alternative to autoclaving. During autoclaving, devices will be exposed to a temperature of 121 oC and 100–100 kPa for a duration of 15–20 min, or to 132 oC at 200 kPa for a duration of 3–5 min. However, many reusable devices cannot withstand the conditions imposed by autoclaving11. This problem is avoided in steam sterilization, which is widely acknowledged as an effective and economic alternative approach for the elimination of viable microorganisms12,13. In particular, exposure to steam causes lethal damage to the bacterial cell envelope and inactivates most toxins by disrupting their structure14. At atmospheric pressure, the saturation temperature of water is ~ 100 oC, which is a temperature that can be tolerated by many materials, including plastics. However, it should be noted that the temperature of steam will change depending on the pressure (see: IAPWS Industrial Formulation 1997 for the Thermodynamic Properties of Water and Steam, https://iapws.org/relguide/IF97-Rev.html).

In recent years, there has been a steep increase in the utilization of alternative materials, such as plastics, for the production of medical devices and instruments. These materials necessitate sterilization or disinfection of the respective devices at relatively low temperatures and, therefore, autoclaving is not an option8,15,16. In parallel, the increasing use of medical devices at home, particularly among patients with chronic illnesses, has raised concerns about the risk of infection due to improper or inadequate disinfection17,18. Moreover, ensuring effective sterilization of such medical devices at home is very challenging in terms of effective pathogen elimination and user safety. Therefore, it is imperative to explore sterilization or disinfection methods that are appropriate for home use. Preferably, such methods involve easy-to-operate equipment that works at relatively low temperatures and atmospheric pressure. This is particularly important if medical devices for home use are very likely to be contaminated with pathogens, as is the case for nebulizers that are often used at home by patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)19,20. This view is underscored by several studies that have documented microbial contamination, including biofilm formation, on home-use medical devices such as nebulizers21,22. Although sterilization of such nebulizers is not strictly necessary in case they are re-used by one and the same patient, thorough cleaning and disinfection are strongly recommended in order to avoid (re)contamination by any opportunistic bacteria the patient may be carrying. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to examine the efficacy of a simple electronic steam machine for home usage in the eradication of a range of potentially dangerous respiratory and other pathogens. In this context, our study evaluates a disinfection method that may offer a practical, affordable, safe, and effective solution for non-professional users in home environments.

Results

Bacterial susceptibility to steam

During usage by patients with asthma or COPD, nebulizers will become contaminated by the microbiota that is present in their mouth and respiratory tract, as well as microbes that are carried on their skin23,24. The greatest risk of subsequent contamination, colonization or infection by the bacteria deposited on the nebulizers will occur if the respective device parts are not immediately properly cleaned upon usage. In such a case, the bacteria will undergo air-drying on the device parts and it may be difficult to fully eradicate them prior to subsequent use of the device. To mimic this situation in a simple model system, we selected a representative panel of respiratory and skin-borne Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial pathogens that are frequently implicated in device-associated infections and that pose a significant threat for frail individuals, such as patients with asthma, COPD, cystic fibrosis (CF), or immunosuppression. The different bacteria were cultured in Lysogeny Broth (LB) and 20 µl aliquots of the respective bacterial suspensions (~ 4–8 × 104 bacteria) were allowed to air-dry in 24-well plates. Subsequently, the plates were exposed to steam at atmospheric pressure for different periods of time, using a X55P0AS-D steam sterilizer. The air-dried bacteria were then resuspended in LB and plated for colony-forming unit (CFU)-counting. In particular, the tested Gram-negative bacteria were Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella oxytoca, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii. While E. coli is a widely investigated Gram-negative model bacterium with significant implications for public health25, K. pneumoniae is a leading cause of pneumonia and other community-acquired respiratory infections26. K. oxytoca is an opportunistic pathogen that is commonly found on mucosal surfaces, including the nasopharynx26. P. aeruginosa is a frequent colonizer of the airways of CF patients that causes a wide range of biofilm-associated respiratory, urinary tract and surgical site infections, as well as bacteremia27,28. Furthermore, A. baumannii is an emerging multidrug-resistant pathogen with a high propensity for biofilm formation that is associated with severe hospital-associated infections, including ventilator-associated pneumonia29. The tested Gram-positive bacteria were Staphylococcus aureus, including various clinical methicillin-sensitive (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant (MRSA) isolates and laboratory strains, and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Both S. aureus and S. epidermidis are frequent causative agents of device-associated infections. Furthermore, S. aureus is a common colonizer of the human skin and mucosa, especially the nasopharynx and lungs of patients with COPD and CF30. It is a notorious pathogen that can cause severe infections of nearly every site of the human body. S. epidermidis is also a common colonizer of the human skin that may cause hard-to-eradicate biofilm-associated infections31. The inclusion of all these different bacterial species and isolates in our study allowed for assessment of the potential clinical relevance of the tested steam disinfection method across a wide range of different infections32,33. As shown in Fig. 1, the susceptibility of the different bacterial strains to disinfection with steam varied depending on the specific strain that was tested. Most tested Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli, K. pneumoniae, K. oxytoca and A. baumannii) trended to be more sensitive to steam than the tested Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus and S epidermidis), with P. aeruginosa showing intermediate sensitivity. Here, it has to be noted that Gram-negative bacteria are generally more sensitive to air-drying than Gram-positive bacteria34,35. Nonetheless, all investigated strains were highly susceptible to disinfection with steam, as evidenced by noticeable reductions in CFU counts already after 10 s of steam exposure. Importantly, a complete elimination of all tested bacterial strains was achieved following a 1-min treatment.

Survival of different bacterial strains upon disinfection with steam. The different plots present the colony-forming units (CFUs) of various bacterial strains before and after steam treatment for 10, 30–60 s and subsequent plating on LB agar: (a). S. aureus ATCC15981 (MSSA); (b). S. aureus E75 (MSSA); (c). S. aureus E166 (MSSA); (d). S. aureus E276 (MSSA); (e). S. aureus USA300 (MRSA); (f). S. aureus HG001 (MSSA); (g). S. epidermidis ATCC35984; h. E. coli ATCC25922; i. P. aeruginosa ATCC27853; j. K. oxytoca; k. K. pneumoniae ATCC15883; and l. A. baumannii ATCC19606. The residual CFU counts are indicated as a percentage of the CFU counts of the inoculum on top of each bar. All experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3). Standard deviations in the CFU counts are indicated by error bars. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Nebulizer handset disinfection

To assess the efficacy of steam in the disinfection of nebulizers for home usage, we applied a type 023 PARI LC SPRINT Nebulizer handset (Fig. 2). This nebulizer is made from polypropylene, thermoplastic elastomer, polyvinyl chloride and cannot be autoclaved without loss of functionality. The handset was disassembled into its constituent parts and, subsequently, the individual parts were intentionally contaminated with bacteria from cultures with an OD600 of 0.05.

The nebulizer’s contaminated upper and lower parts, and the mouthpiece were replica plated onto LB agar before and after disinfection with steam. Bacteria contaminating the connection tube and nozzle attachment were collected by swabbing and, subsequently, plated on LB agar. As depicted in Fig. 3, which presents the results of one of the three independent experimental replicates, a 60-s exposure to steam successfully eradicated all 12 tested bacterial species. The absence of CFUs was consistent across all samples and replicates, indicating the complete eradication of viable bacteria from the upper and lower body of the nebulizer, the mouthpiece, the connection tubing, and the nozzle attachment. Importantly, the two independent detection methods, i.e. direct replica plating and indirect swab-based plating, produced concordant results, which reinforces the reliability of the outcome. These findings demonstrate that steam treatment for 1 min at atmospheric pressure is sufficient to disinfect complex, multi-component medical devices, such as a nebulizer, even in the presence of high microbial loads.

Disinfection of nebulizer parts with steam. The different parts of a PARI LC SPRINT Nebulizer handset were contaminated with: (a) S. aureus ATCC15981; (b) S. aureus E75; (c) S. aureus E166; (d) S. aureus E276; (e) S. aureus USA300; (f) S. aureus HG001; (g) S. epidermidis ATCC35984; (h) E. coli ATCC25922; (i) P. aeruginosa ATCC27853; (j) K. oxytoca; (k) K. pneumoniae ATCC15883; (l) A. baumanni ATCC19606. Prior and after 60 s steam exposure, the contaminated mouth piece was replica-plated on LB agar. Bacteria contaminating the connection tube and nozzle were collected by swabbing and subsequently plated on LB agar. Of note, the different bacterial loads on the contaminated nebulizer parts were not quantified. Upper left plate of each panel, replica-plated contaminated mouthpiece; lower left plate, replica-plated contaminated mouthpiece after disinfection with steam; upper right part plate, bacteria contaminating the connection tube and nozzle; lower right plate, bacteria contaminating the connection tube and nozzle after steam disinfection. Three independent replicate experiments were performed (n = 3).

In addition to the intentional contamination of device parts with bacteria, a negative control experiment was performed where environmental contamination of the device parts due to manual handling or by air-borne bacteria was tested before and after steam disinfection. As expected, this revealed low-level bacterial growth on LB agar plates upon direct replica plating and indirect swab-based plating (Fig. 4, panels A and B). However, after 1 min of steam treatment, no bacterial colonies were observed on either replica-plated or swab-streaked LB plates (Fig. 4, panels C and D). This shows that the steam disinfection process was also effective in eliminating environmental contaminants acquired under typical handling conditions.

Steam disinfection eliminates low-level environmental contamination from nebulizer parts. A PARI LC SPRINT Nebulizer handset was handled under standard laboratory conditions without deliberate bacterial inoculation to simulate real-world environmental exposure. (A) Replica plating of the nebulizer body (upper/lower parts, mouthpiece as in Fig. 3) before steam treatment, and (B) plating of swabs from the inner and outer surfaces of the connection tubing (as in Fig. 3) prior disinfection yielded only few CFUs. After 1-min steam disinfection, no visible colony growth was observed on either replica-plated (C) or swab-streaked (D) plates. Plating was performed on LB agar and the plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C. Experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3).

To assess the effects of steam disinfection on the nebulizer’s tubing, the connection tube was exposed to either conventional autoclave-based steam sterilization at 121 °C, or to steam disinfection at atmospheric pressure. After conventional autoclaving, the tubing exhibited a noticeable whitening and loss of transparency, indicative of material degradation (Fig. 5). In contrast, the tube exposed to steam disinfection at atmospheric pressure retained its original clarity and appearance, indistinguishable from the untreated tube (Fig. 5). These observations show that the gentler steam disinfection method does not visibly affect the structural integrity of the tubing and may be more compatible with thermosensitive medical-grade plastics.

Comparison of nebulizer tube appearance upon conventional steam sterilization and steam disinfection at 100 °C. Top: untreated tube; Bottom left: tube after traditional autoclave-based steam sterilization (121 °C, 15 min, 100–110 kPa); Bottom right: tube after treatment with the X55P0AS-D steam sterilizer (~ 100 °C, 1 min, atmospheric pressure). Whitening and loss of transparency are observed following conventional steam sterilization, while the atmospheric pressure steam-treated tube retains the appearance of the untreated control.

Biofilm reduction and eradication of biofilm-embedded bacteria

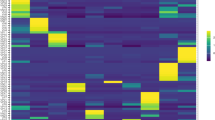

To determine whether bacterial biofilms will be reduced by disinfection with steam, and how this impacts on the viability of bacteria embedded in a biofilm, the different bacterial strains were allowed to form biofilms in 96-well plates. Subsequently, biofilm formation was visualized by staining with crystal violet (Fig. 6a) and quantified by dissolving the crystal violet in ethanol and assessing the amount of dissolved crystal violet with a spectrophotometer (Fig. 6b). The results show that steam treatment caused a measurable reduction in the biomass of biofilms for several strains, with significant reductions (p < 0.05) observed for S. aureus ATCC15981, E276 and USA300, S. epidermidis, E. coli, K. oxytoca, K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii. These effects became especially pronounced after 5–10 min of steam exposure. However, for some strains, including S. aureus strains E75, E166 and HG001, and P. aeruginosa, no statistically significant biomass reduction was observed. This may reflect strain-specific differences in biofilm composition and structure, such as variations in extracellular matrix density, exopolysaccharide production or heat resistance of the biofilm matrix. Next, we investigated whether the steam disinfection process would kill all the bacteria within the different biofilms. After culturing for 24 h, the resulting biofilms contained between 1.27*108 and 9.6*108 CFUs (Table 1). Following 1 min of steam exposure, bacterial viability within the biofilms was reduced by approximately 99.9% across all tested strains. Notably, after 5 min of treatment, no viable bacteria could be detected in any of the biofilm samples (detection limit < 100 CFU/mL), indicating complete inactivation. These observations indicate that, while biofilm biomass may not visibly decrease in all cases, the steam disinfection method is highly effective in eliminating biofilm-associated viable bacteria after only short exposure times.

Effects of steam exposure on bacterial biofilms. Biofilms of different bacterial species were allowed to form in 96-well micro liter plates during 24 h of growth. Subsequently, the biofilms were exposed to steam for 1, 5–10 min. The biofilms and a non-sterilized control plate were then stained with crystal violet (a). In addition, the crystal violet retained by the biofilms was dissolved in ethanol and the released crystal violet was quantified spectrophotometrically (b). The bacterial strains used were S. aureus ATCC15981, S. aureus E75, S. aureus E166, S. aureus E276, S. aureus USA300, S. aureus HG001, S. epidermidis ATCC35984, E. coli ATCC25922, P. aeruginosa ATCC27853, K. oxytoca, K. pneumoniae ATCC15883 and A. baumannii ATCC19606. Experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3). Standard deviations in the CFU counts are indicated by error bars. *, P < 0.05.

Discussion

The present study was aimed at investigating whether portable, low pressure steam sterilizers can be applied for the effective disinfection of reusable biomedical materials and devices, which were purposely contaminated with high titers of different respiratory or skin-borne human pathogens. The results show that steam disinfection successfully eradicated the applied pathogens at atmospheric pressure, including both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. These included S. aureus (including MRSA), S. epidermidis, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, K. oxytoca, K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii. Air-dried bacterial contaminants were subjected to a one-min steam exposure, resulting in their complete eradication. Furthermore, the applied approach allowed effective disinfection of the internal components of a medical device, as demonstrated with a nebulizer for home use. Importantly, even biofilm-embedded bacteria were effectively inactivated, which is notable given their known resistance to many disinfection methods36,37. These findings are particularly relevant in light of previous reports showing that conventional household cleaning procedures are often insufficient to fully eliminate biofilms and resistant pathogens from home-use medical devices38. This is in contrast to alternative portable disinfection devices, such as UV lamps, which primarily inhibit microbial replication and may fail to achieve complete inactivation39. In addition, UV lamps may prove ineffective if the UV light fails to adequately cover the entire surface of a medical device that needs to be disinfected, and they may suffer from inadequate design for handling by people who are not familiar with aseptic procedures40,41,42,43. An additional advantage of the applied steam disinfection approach is that it is time-efficient and capable of decontaminating both transparent and non-transparent medical devices as exemplified by our experiments with the nebulizer.

Steam sterilization has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the USA for disinfection of biomedical implants (Sterilization for Medical Devices | FDA). Steam was also shown to be effective for the decontamination of medical devices for home use44. In comparison to other FDA-approved methods, such as gamma irradiation, electron-beam (E-beam) and Eto gas45,46, steam sterilization offers numerous advantages, especially the absence of radioactivity and toxic chemicals, low cost, easy and rapid operation and, last but not least, a high efficacy in the elimination of bacteria47. While gamma irradiation and E-beam irradiation are highly energetic sterilization modalities with excellent penetration capabilities, they also generate free radicals and necessitate specific operational conditions, making them unsuitable for home use. Eto gas sterilization offers the possibility to eliminate contaminants from medical devices by alkylating the nitrogenous backbone of DNA. However, as a chemical sterilant, Eto may react with certain medical devices made of polymer composites that contain nucleophilic components. This reaction can lead to permanent alterations in the chemical composition, as well as the structure and functionality of the device48,49. In comparison to the afore-mentioned methods, traditional heat-based sterilization methods have the potential to induce protein denaturation and coagulation. Dry heat sterilization at 160 °C for 120 min, in particular, is widely employed due to its prevalence, convenience, and effectiveness in decontamination. In contrast, the traditional steam heat sterilization involves a temperature of 121 oC and a pressurized environment of 100–110 kPa for a duration of 15–20 min, or 134 oC at ~ 200 kPa for 3–5 min. This prolonged exposure to high temperature and pressure may result in the melting of crystalline domains and the formation of physical crosslinks upon cooling. This process can potentially compromise the biocompatibility of certain plastic medical devices47. Furthermore, the effectiveness of steam sterilization is contingent upon the proper sealing of the machine and the attainment of the required pressure and temperature levels. These conditions, alongside the need for dedicated infrastructure and trained personnel to ensure appropriate operation and the avoidance of burns or other accidents, often limit the use of traditional steam sterilization in non-clinical environments.

Traditional steam sterilization also has various other limitations. For instance, due to the inherent constraints associated with non-automated reprocessors, the utilization of liquid chemical sterilants should be limited to the reprocessing of critical devices that are heat sensitive and incompatible with alternative sterilization methods. Most of the reused medical devices are based on plastic materials and they are sensitive to high temperatures, whereas the high temperature and pressure could destroy the structure of medical devices. Moreover, during the process of sterilization some toxic agents may emerge that pose a risk for human health and should not come into direct contact with the human body50,51. Overall, these considerations highlight the potential limitations of the traditional steam sterilization processes. In contrast, our study provides a safer and more medical device-friendly way of steam disinfection, which involves a steam machine that generates steam with a temperature of ~ 100 oC at atmospheric pressure. As exemplified with the X55P0AS-D steam machine, such devices can be designed for intuitive operation, allowing safe and effective usage with minimal training. Using such a device, the risks of burns is minimal, albeit that this will depend on user adherence to the manual as steam of ~ 100 oC has the inherent potential to cause burns. In our present study, we also demonstrate that steam can be used to disinfect devices made from polypropylene, thermoplastic elastomer, and polyvinyl chloride, which are among the most common materials used in medical devices52,53. Consequently, this process is apparently suitable for usage in home settings or, for instance, community health centers without the infrastructure for traditional steam sterilization. This is particularly important for individuals using nebulizers or other home-based respiratory devices who are at elevated risk of infection from opportunistic or antibiotic-resistant pathogens, such as MRSA, A. baumannii or P. aeruginosa54.

We acknowledge that our present study also has certain limitations. In particular, it was conducted under controlled laboratory conditions using individual bacterial strains and ideal cleaning scenarios. The bacterial loads used in our experiments (approximately 2–4 × 10⁶ CFU/mL) were intentionally selected to represent high-challenge conditions, exceeding the typical microbial contamination levels reported on medical devices for home-use, which are often in the range of ~ 2 to ~ 200 CFU, depending on user behavior, cleaning frequency and environmental exposure55,56,57. By testing under worst-case scenarios, we aimed to assess the maximum efficacy of the steam disinfection approach. Nonetheless, we realize that real-world contamination is highly variable, and the effectiveness of disinfection may be influenced by factors, such as organic soiling, device geometry and the nature of microbial biofilms. We therefore regard this variability as a key limitation of our present study and emphasize the need for future studies that simulate a broader range of contamination levels to validate the robustness of this disinfection approach. Another potential limitation of our current study is that it was conducted with individual bacterial type strains and clinical isolates. Upon usage by patients in real-world scenarios, devices may be contaminated with multiple different and highly resilient microorganisms, including pathogenic spore-formers (e.g. clostridia) and viruses. Such contaminants may be more difficult to eradicate, as is the case when polymicrobial biofilms are formed58,59,60. Also, such devices may have more complex geometries, consist of different materials, and they may have been inadequately cleaned after usage, which will make effective disinfection more challenging. In addition, surface complexity, mixed materials, and improper pre-cleaning could impair the disinfection efficacy. Lastly, long-term safe use of a steam machine will also require user awareness of maintenance needs (e.g. descaling and water tank cleaning) and periodic safety checks. It will therefore be important to further test the efficacy of disinfection of medical devices with steam under real-life conditions, including repeated usage cycles, incomplete cleaning steps, and broader pathogen diversity.

In conclusion, this study provides proof-of-concept evidence that a portable and affordable steam machine that operates at atmospheric pressures can effectively disinfect reusable medical devices under controlled laboratory conditions. Its ease of use, compatibility with common thermosensitive materials, and ability to inactivate biofilm-associated and antibiotic-resistant pathogens support its potential integration into home healthcare routines. Importantly, the broader impact of this approach lies in its potential contribution to infection prevention in vulnerable populations, leading to improved public health outcomes and enhanced safety in non-clinical settings. Implementation of such user-friendly disinfection technologies could reduce the burden of device-related infections in aging, immunocompromised and other at-risk populations, and decrease dependence on centralized healthcare facilities. Nevertheless, further research, including clinical validation involving patients with chronic respiratory conditions using nebulizers at home, long-term usage studies and real-world performance assessments including a wider range of reusable medical devices and materials, will be essential to confirm its safety, effectiveness, and applicability under practical conditions. Long-term usage studies should also involve a critical evaluation of the safety of materials used for the construction of steam machines intended for home usage, including formal toxicity testing. Lastly, this technology may also prove beneficial in other disinfection-reliant domains, such as food safety, veterinary medicine, and community health programs.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

We used the following strains: S. aureus ATCC15981, clinical S. aureus isolates E75, E166, E276 from the UMCG strain collection, S. aureus USA300 (MRSA)61, and S. aureus HG00162, S. epidermidis ATCC35984, E. coli ATCC25922, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853, K. oxytoca63, K. pneumoniae ATCC15883, and A. baumanni ATCC19606. All strains were routinely stored at -80 oC. They were then cultured in LB overnight at 37 oC with shaking at 250 rpm. On the following day, 10 µl of medium were added to 5 ml of fresh LB, and culturing was continued under the same conditions for an additional 2–3 h until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was in the range of 0.4 to 0.6.

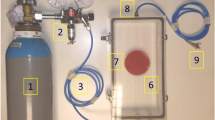

For the present study a X55P0AS-D (Moni Trade LTD, Bulgaria) steam machine was used. This device consists of several components, including a Lid, Tray, Sterilizer body, and Base (Fig. 7). Prior to initiating the disinfection process, it is necessary to pour 80 ml of water into the reservoir located in the base of the machine. When switched on, the machine will automatically heat up and be filled with steam in ~ 110 s, including ~ 10 s warm-up time, ~ 45 s for heating up and ~ 55 s for full exposure of the contents to steam of ~ 100 oC at atmospheric pressure (220–240 V; 50/60 HZ; 330 W). Thereafter steam disinfection can be continued for the desired period of time. During the heating process the lid needs to be kept closed in order to maintain microbiological containment and to prevent burns of the operator. Heating of the steam machine was verified (Fig. 8) using a 62 mini InfraRed (IR) thermometer (FLUKE, the Netherlands) by measuring the temperature of the Base, which contains the heating device.

Bacterial susceptibility to steam disinfection

To assess the susceptibility of bacteria to steam disinfection, the bacteria were cultured as described above and diluted to a concentration of 2–4 × 106 colony-forming units (CFU)/ml (OD600 of 0.05). Subsequently, 20 µl of the bacterial suspension were immediately applied to 24-well plates (Greiner Bio-one, Germany) and allowed to air-dry in a laminar flow cabinet at room temperature for a duration of 1.5 h. Following the drying process, the plates were subjected to steam disinfection. To this end, the steam machine was allowed to build up steam and, subsequently, the plates with bacteria were inserted for about 10 s, 30 s, or 1 min after which they were taken out of the machine. Next, the bacteria were collected by washing each well with 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The bacterial survival was quantified by plating on LB agar plates, overnight incubation at 37 oC and CFU-counting.

Nebulizer

To test device decontamination by steam sterilization, we used a type 023 PARI LC SPRINT Nebulizer (PARI LC SPRINT, Germany). This portable nebulizer is used for the pulmonary delivery of drug aerosols in patients with asthma or COPD64. The employed nebulizer consists of five parts that can be separated, namely an upper part, a mouthpiece, a nozzle attachment, a lower part, and a connection tubing (Fig. 2).

Visual inspection of material integrity following steam disinfection

To evaluate potential material degradation or safety concerns associated with steam disinfection, a comparative analysis was performed on the nebulizer’s connection tubing. Three sets of tubes were prepared: one untreated (control), one subjected to traditional high-pressure steam sterilization (121 °C, 15 min, 100–110 kPa), and one treated with the X55P0AS-D steam machine at ~ 100 °C for 1 min under atmospheric pressure. After treatment, the tubes were visually inspected for discoloration, warping, or other signs of material alteration. Changes in transparency and color were used as qualitative indicators of possible degradation, which may be associated with thermal instability or the release of chemical by-products.

Microbial contamination and decontamination of nebulizers

To investigate the efficacy of steam in the disinfection of the nebulizer, the device surfaces were intentionally contaminated by bringing them into contact with bacterial suspensions in PBS at 2–4 × 106 CFU/ml (OD600 of 0.05). Immediately after bacterial contamination, the nebulizer’s upper and lower parts and the mouthpiece were replica-plated, i.e. gently pressed onto LB agar plates (OXOID, UK), for 5–10 s with consistent downward pressure, ensuring contact without damaging the agar surface. The plates were subsequently incubated overnight at 37 oC. Bacteria on the inside and outside surfaces of the connection tubing and nozzle attachment were collected with dry sterile swab sticks (Medical Wire Co Ltd, UK) and, subsequently, streaked on agar plates. Afterwards, the contaminated device parts were allowed to air dry in a flow cabinet for 30 min. Subsequently, these contaminated device parts were subjected to a 1-min steam treatment. Following the treatment, two methods were employed to evaluate the disinfection efficacy. Firstly, the device parts were replica-plated (i.e. gently pressed) onto LB agar as described above. Secondly, sterile cotton swabs were used to collect bacteria from the different surfaces and, subsequently, streaked onto plates as described above. After incubation overnight at 37 °C, bacterial growth was assessed. The presence of visible colonies on the replica-plated agar surface or swab-streaked plates was considered indicative of surviving bacteria. In contrast, the complete absence of colony formation was interpreted as successful disinfection. For each treatment condition, three independent experiments were conducted. Results were recorded as “growth” or “no growth” to determine qualitative disinfection efficacy.

Negative control experiment for environmental contamination

To evaluate potential environmental contamination during the experimental procedures, a negative control group was included. In this control, the medical device parts (nebulizer and tubing) were handled under standard laboratory conditions, including brief exposure to ambient air and contact with gloved hands, but were not intentionally contaminated with bacterial suspensions. Prior to steam disinfection, the different components of the nebulizer (upper part, lower part, and mouthpiece) were replica plated (i.e. gently pressed) onto LB agar plates as described above. In parallel, the inner and outer surfaces of the connection tubing were swabbed using dry sterile cotton swabs (Medical Wire Co Ltd, UK), and the swabs were streaked onto LB agar plates as above. All plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C. After this handling for pre-treatment evaluation, the same device components were subjected to a 1-min steam disinfection under atmospheric pressure using the X55P0AS-D device. Following steam disinfection, the nebulizer parts were replica-plated on LB agar and swab samples from the tubes were streaked on LB agar as described above to assess the presence or absence of viable bacterial contaminants.

Disinfection of bacterial biofilms

To investigate the effects of steam disinfection on bacterial biofilms, bacteria were grown overnight in tryptic soy broth (TSB) and subsequently diluted in TSB with 4% glucose to an OD600 of 0.1. Aliquots of 100 µl of the diluted culture were transferred to a 96-well plate, which was incubated at 37 oC for 24 h without shaking. Subsequently, the plates containing bacterial biofilms were subjected to steam for 0 (control), 1, 5, or 10 min, respectively. Following the treatment, the residual biofilm was stained with 2.3% crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the supplier’s instructions. Lastly, the crystal violet bound to the biofilm was dissolved using 75% ethanol and quantified using a plate reader (Epoch2, Biotek) at a wavelength of 570 nm. In parallel, the viability of biofilm-embedded bacteria prior and after steam disinfection was tested by resuspension of the residual biofilm in PBS and CFU-counting after 1, 5–10 min steam treatment.

Statistical analyses

All experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3). The data was analyzed using the student t-test in the Graphpad Prism software package version 9.0, with a confidence level of 95%. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Data availability

All data generated and analysed during the current study are included in this manuscript.

References

Rowan, N. J., Kremer, T. & McDonnell, G. A review of spaulding’s classification system for effective cleaning, disinfection and sterilization of reusable medical devices: viewed through a modern-day lens that will inform and enable future sustainability. Sci. Total Environ. 878, 162976 (2023).

Mohapatra, S. Sterilization and Disinfection. Essentials of Neuroanesthesia. 929 – 44. (2017).

, E. H. &, C. (eds) BS,., Preserv. Philadelphia Lea Febige Chemical disinfection of medical and surgical materials. Disinfect sterilization. 517–31. (1968).

Wells-Bennik, M. H. J. et al. Heat resistance of spores of 18 strains of Geobacillus stearothermophilus and impact of culturing conditions. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 291, 161–172 (2019).

de Sousa Iwamoto, L. A., Duailibi, M. T., Iwamoto, G. Y., de Oliveira, D. C. & Duailibi, S. E. Evaluation of ethylene oxide, gamma radiation, dry heat and autoclave sterilization processes on extracellular matrix of biomaterial dental scaffolds. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 4299 (2022).

Rutala, W. A. & Weber, D. J. New disinfection and sterilization methods. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7 (2), 348–353 (2001).

Dhaliwal, J. S. et al. Microbial biofilm decontamination on dental implant surfaces: A Mini review. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11, 736186 (2021).

Rutala, W. A. & Weber, D. J. Disinfection and sterilization in health care facilities: an overview and current issues. Infect. Dis. Clin. North. Am. 35 (3), 575–607 (2021).

van Doornmalen, J. & Kopinga, K. Review of surface steam sterilization for validation purposes. Am. J. Infect. Control.. 36 (2), 86–92 (2008).

Tabatabaii, S. A. et al. Microbial contamination of home nebulizers in children with cystic fibrosis and clinical implication on the number of pulmonary exacerbations. BMC Pulm. Med. 20 (1), 33 (2020).

Tangpothitham, S., Pongprueksa, P., Inokoshi, M. & Mitrirattanakul, S. Effect of post-polymerization with autoclaving treatment on monomer elution and mechanical properties of 3D-printing acrylic resin for splint fabrication. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 126, 105015 (2022).

Panta, G., Richardson, A. K. & Shaw, I. C. Effectiveness of autoclaving in sterilizing reusable medical devices in healthcare facilities. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 13 (10), 858–864 (2019).

Sabnis, R. B., Bhattu, A. & Vijaykumar, M. Sterilization of endoscopic instruments. Curr. Opin. Urol. 24 (2), 195–202 (2014).

Brydon, N. Endotoxin is inactivated by ethylene oxide, gamma, Electron beam, and steam sterilization. Biomed. Instrum. Technol. 57 (3), 98–105 (2023).

Sadr, S. J., Fayyaz, A., Mahshid, M., Saboury, A. & Ansari, G. Steam sterilization effect on the accuracy of friction-style mechanical torque limiting devices. Indian J. Dent. Res. 25 (3), 352–356 (2014).

Wiessner, R. et al. Alterations in the mechanical, chemical and biocompatibility properties of low-cost polyethylene and polyester meshes after steam sterilization. Hernia 24 (6), 1345–1359 (2020).

Tesini, B. L. & Dumyati, G. Health Care-Associated infections in older adults: epidemiology and prevention. Infect. Dis. Clin. North. Am. 37 (1), 65–86 (2023).

Dix, L. M. L., de Goeij, I., Manintveld, O. C., Severin, J. A. & Verkaik, N. J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa left ventricular assist device (LVAD) driveline infection acquired from the bathroom at home. Am. J. Infect. Control. 50 (12), 1392–1394 (2022).

Cavallo, F. M., Kommers, R., Friedrich, A. W., Glasner, C. & van Dijl, J. M. Exploration of oxygen-mediated disinfection of medical devices reveals a high sensitivity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to elevated oxygen levels. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 18243 (2022).

Torres, A., Blasi, F., Dartois, N. & Akova, M. Which individuals are at increased risk of Pneumococcal disease and why? Impact of COPD, asthma, smoking, diabetes, and/or chronic heart disease on community-acquired pneumonia and invasive Pneumococcal disease. Thorax 70 (10), 984–989 (2015).

Bouhrour, N., Nibbering, P. H. & Bendali, F. Medical Device-Associated biofilm infections and Multidrug-Resistant pathogens. Pathogens ;13(5). (2024).

Harris, J. C. et al. Bacterial surface detachment during nebulization with contaminated reusable home nebulizers. Microbiol. Spectr. 10 (1), e0253521 (2022).

Swanson, C. S. et al. Microbiome-scale analysis of aerosol facemask contamination during nebulization therapy in hospital. J. Hosp. Infect. 134, 80–88 (2023).

Wei, Q. & Ma, L. Z. Biofilm matrix and its regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14 (10), 20983–21005 (2013).

Nasrollahian, S., Graham, J. P. & Halaji, M. A review of the mechanisms that confer antibiotic resistance in pathotypes of E. coli. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 14, 1387497 (2024).

Podschun, R. & Ullmann, U. Klebsiella spp. As nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11 (4), 589–603 (1998).

Naehrig, S., Chao, C. M. & Naehrlich, L. Cystic fibrosis. Dtsch. Arztebl Int. 114 (33–34), 564–574 (2017).

Mulcahy, L. R., Isabella, V. M. & Lewis, K. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in disease. Microb. Ecol. 68 (1), 1–12 (2014).

Ibrahim, S., Al-Saryi, N., Al-Kadmy, I. M. S. & Aziz, S. N. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii as an emerging concern in hospitals. Mol. Biol. Rep. 48 (10), 6987–6998 (2021).

Raineri, E. J. M., Altulea, D. & van Dijl, J. M. Staphylococcal trafficking and infection-from ‘nose to gut’ and back. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. ;46(1). (2022).

Burke, Ó., Zeden, M. S. & O’Gara, J. P. The pathogenicity and virulence of the opportunistic pathogen Staphylococcus epidermidis. Virulence 15 (1), 2359483 (2024).

Kao, C. M. & Fritz, S. A. Infection prevention-how can we prevent transmission of community-onset methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 31 (2), 166–172 (2025).

Sibila, O. et al. Risk factors and antibiotic therapy in P. aeruginosa community-acquired pneumonia. Respirology 20 (4), 660–666 (2015).

de Goffau, M. C., van Dijl, J. M. & Harmsen, H. J. Microbial growth on the edge of desiccation. Environ. Microbiol. 13 (8), 2328–2335 (2011).

de Goffau, M. C., Yang, X., van Dijl, J. M. & Harmsen, H. J. Bacterial pleomorphism and competition in a relative humidity gradient. Environ. Microbiol. 11 (4), 809–822 (2009).

Maillard, J. Y. & Centeleghe, I. How biofilm changes our Understanding of cleaning and disinfection. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 12 (1), 95 (2023).

Li, C. & Xin, W. Different disinfection strategies in bacterial and biofilm contamination on dental unit waterlines: A systematic review. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. (2025).

Talsma, S. S. Biofilms on medical devices. Home Healthc. Nurse. 25 (9), 589–594 (2007).

Sinha, A. K., Løbner-Olesen, A. & Riber, L. Bacterial chromosome replication and DNA repair during the stringent response. Front. Microbiol. 11, 582113 (2020).

Nerandzic, M. M., Cadnum, J. L., Eckart, K. E. & Donskey, C. J. Evaluation of a hand-held far-ultraviolet radiation device for decontamination of Clostridium difficile and other healthcare-associated pathogens. BMC Infect. Dis. 12, 120 (2012).

Raeiszadeh, M. & Adeli, B. A critical review on ultraviolet disinfection systems against COVID-19 outbreak: applicability, validation, and safety considerations. ACS Photonics. 7 (11), 2941–2951 (2020).

Ramos, C. C. R. et al. Use of ultraviolet-C in environmental sterilization in hospitals: A systematic review on efficacy and safety. Int. J. Health Sci. (Qassim). 14 (6), 52–65 (2020).

Vignali, V. et al. An efficient UV-C disinfection approach and biological assessment strategy for microphones. Appl. Sci. 12 (14), 7239 (2022).

Li, D. F. et al. Steam treatment for rapid decontamination of N95 respirators and medical face masks. Am. J. Infect. Control. 48 (7), 855–857 (2020).

Rizwan, M., Chan, S. W., Comeau, P. A., Willett, T. L. & Yim, E. K. F. Effect of sterilization treatment on mechanical properties, biodegradation, bioactivity and printability of GelMA hydrogels. Biomed. Mater. 15 (6), 065017 (2020).

Komolprasert, V., McNeal, T. P. & Begley, T. H. Effects of gamma- and electron-beam irradiation on semi-rigid amorphous polyethylene terephthalate copolymers. Food Addit. Contam. 20 (5), 505–517 (2003).

Bharti, B., Li, H., Ren, Z., Zhu, R. & Zhu, Z. Recent advances in sterilization and disinfection technology: A review. Chemosphere 308 (Pt 3), 136404 (2022).

Jarvis, S. et al. Microbial contamination of domiciliary nebulisers and clinical implications in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMJ Open. Respir Res. 1 (1), e000018 (2014).

Tipnis, N. P. & Burgess, D. J. Sterilization of implantable polymer-based medical devices: A review. Int. J. Pharm. 544 (2), 455–460 (2018).

Burkhardt, F. et al. Dimensional accuracy and simulation-based optimization of polyolefins and biocopolyesters for extrusion-based additive manufacturing and steam sterilization. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 153, 106507 (2024).

Fernie, K., Hamilton, S. & Somerville, R. A. Limited efficacy of steam sterilization to inactivate vCJD infectivity. J. Hosp. Infect. 80 (1), 46–51 (2012).

Czuba, L. Application of plastics in medical devices and equipment. Handb. Polym. Appl. Med. Med. Devices :9–19. (2014).

Vienken, J. & Boccato, C. Do medical devices contribute to sustainability? The role of innovative polymers and device design. Int. J. Artif. Organs. 47 (4), 240–250 (2024).

Qin, S. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: pathogenesis, virulence factors, antibiotic resistance, interaction with host, technology advances and emerging therapeutics. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 7 (1), 199 (2022).

Garvey, M. Medical Device-Associated healthcare infections: sterilization and the potential of novel biological approaches to ensure patient safety. Int. J. Mol. Sci. ;25(1). (2023).

Riquena, B. et al. Microbiological contamination of nebulizers used by cystic fibrosis patients: an underestimated problem. J. Bras. Pneumol.. 45 (3), e20170351 (2019).

Ranjan, N., Singla, N., Guglani, V., Randev, S. & Kumar, P. Bacterial colonization of home nebulizers used by children with recurrent wheeze. Indian Pediatr. 59 (5), 377–379 (2022).

Mishra, A., Aggarwal, A. & Khan, F. Medical Device-Associated infections caused by Biofilm-Forming microbial pathogens and controlling strategies. Antibiot. (Basel). 13, 7 (2024).

Sagripanti, J. L. & Bonifacino, A. Bacterial spores survive treatment with commercial sterilants and disinfectants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65 (9), 4255–4260 (1999).

Cavari, Y. et al. Healthcare workers mobile phone usage: A potential risk for viral contamination. Surveillance pilot study. Infect. Dis. (Lond). 48 (6), 432–435 (2016).

Glasner, C. et al. Rapid and high-resolution distinction of community-acquired and nosocomial Staphylococcus aureus isolates with identical pulsed-field gel electrophoresis patterns and spa types. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 303 (2), 70–75 (2013).

Herbert, S. et al. Repair of global regulators in Staphylococcus aureus 8325 and comparative analysis with other clinical isolates. Infect. Immun. 78 (6), 2877–2889 (2010).

García-Pérez, A. N. et al. From the wound to the bench: exoproteome interplay between wound-colonizing Staphylococcus aureus strains and co-existing bacteria. Virulence 9 (1), 363–378 (2018).

Martin, A. R. & Finlay, W. H. Nebulizers for drug delivery to the lungs. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 12 (6), 889–900 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Berry Hulleman and Edo Ebskamp for providing the X55P0AS-D steam sterilizer and the PARI LC SPRINT Nebulizer handset.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.W. and J.M.v.D conceived the project plan; S.W. performed the experiments; S.W. and J.M.v.D. analyzed the data; S.W. drafted the manuscript; and S.W. and J.M.v.D. edited the manuscript. Both authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, S., van Dijl, J. Disinfection of medical devices with a steam machine that operates at atmospheric pressure and is suitable for home usage. Sci Rep 15, 25486 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11509-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11509-6