Abstract

This original research details the development of the UK’s first osteopathic Practice-Based Research Network (PBRN), the NCOR Research Network, which represents a significant advancement in research capacity. This intellectually coherent framework provides essential baseline data on practitioners, their clinical activities, and patient demographics, with significant potential to influence professional development, education, and healthcare policy. Data were collected through a cross-sectional online survey study conducted between September 2023 and December 2023. The study included 570 osteopaths registered with the General Osteopathic Council who consented to participate in the NCOR Research Network. We examined demographic characteristics of osteopaths, details of their clinical practice, patient demographics, common presenting complaints, treatment approaches, and attitudes towards evidence-based practice. The median age bracket of participants was 50–59 years, with 55% identifying as women. Participants had a median of 17 years of clinical experience. Most worked in private practice (71% as principals, 32% as associates), seeing 20–39 h of patients per week. The majority (87%) regularly treated adults aged 65 or older. Low back pain was the most common complaint seen daily (56%). Spinal articulation/mobilization (79%) and soft tissue massage (78%) were the most frequently used techniques. Participants reported positive views towards evidence-based practice but cited lack of research skills and time as barriers to engagement. The NCOR Research Network provides a foundation for future osteopathic research in the UK. While the sample was not fully representative of UK osteopaths, it offers insights into current osteopathic practice. The network aims to foster collaboration between clinicians and academics, potentially bridging the gap between research and practice in osteopathy. Protocol registration: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HPWG4

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteopathy is a regulated profession in the United Kingdom (UK) and is an Allied Health Profession (AHP) in England. Osteopaths principally manage patients with persistent musculoskeletal (MSK) presentations, delivering packages of care using a variety of strategies including manual therapy, self-management, education, and reassurance1. Most osteopaths in the UK are self-employed and work alone1. The General Osteopathic Council (GOsC), the professional regulator, revised its continuing professional development requirements in 2018 to promote reflective learning and professional interaction. These changes introduced mandatory objective activities that require osteopaths to engage in case discussions with colleagues, collect patient feedback or data using Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs), conduct peer observations, or perform clinical audits2. Throughout the UK, there are several regional societies to promote collaboration and shared learning opportunities for osteopaths, as working in isolation is seen as a potential risk for burnout and patient safety issues3. However, accessibility to these societies due to geographical dispersion may be limited4. Consequently, there is a need to develop an easily accessible network of osteopaths to support shared learning and participation in activities.

There appears to be a discrepancy between the range of conditions treated in everyday osteopathic practice throughout the UK and the available research evidence supporting these treatments. An umbrella review found promising evidence regarding osteopathic care for MSK disorders, but limited and inconclusive evidence for paediatric conditions, primary headache and irritable bowel syndrome5. However, non-MSK disorders are commonly treated by osteopaths in clinical practice, despite the lack of evidence for this approach1. Consequently, we need a better understanding of what happens in osteopathic clinical practice. This requires gathering more high-quality evidence about osteopaths’ clinical activities and approaches. We need more evidence, of better quality, about what osteopaths do in their clinics. The quality of existing evidence is limited by methodological issues such as small sample sizes, lack of prospective designs, and limited geographical coverage as noted in previous reviews of osteopathic research5,6. Furthermore, we need to assess whether current clinical practice aligns with best available evidence. Where discrepancies exist, there is a need to develop and test interventions to address these gaps.

Translating evidence into practice is a challenging endeavour, with a time lag of 17 years commonly cited7. This challenge is even more problematic when the amount of evidence is growing exponentially8. One way to favour the evidence being disseminated to clinicians, is to involve them in the different phases of research projects, from topic selection to dissemination, increasing engagement with evidence and fostering a sense of ownership.

One particularly innovative mechanism many professions have used to bridge this gap is through the creation of Practice-Based Research Networks (PBRNs). These represent transformative collaborations between clinicians and academics, fundamentally changing how research is conducted by fostering rigorous investigations in everyday clinical practice. The establishment of such networks has the potential to greatly advance osteopathic knowledge and practice by generating contextually relevant evidence. They are a useful tool to invite clinicians in day-to-day practice to contribute to national research agenda and improvement initiatives9,10. They also allow clinicians to contribute data on practice-relevant topics, which in turn can identify pertinent research questions for further exploration11. A PBRN requires a minimum of 15 outpatient practices and/or 15 clinicians to collaborate with academic institutions to conduct research12. The development of a PBRN is a good way for a profession to develop a research infrastructure that goes beyond a single study and acts as a springboard for sub-studies13. As of 2025, active osteopathic PBRNs exist in several countries globally, including the ORION network in Australia14 (established 2016), the OPERA network in New Zealand13 (established 2018), and the DO-Touch.NET in the USA15 (established 2010).

Engagement in research activities among healthcare professionals can vary considerably16,17. This variability is often attributed to multiple factors, including the extent of research training embedded in professional education curricula16. The educational qualifications for osteopaths in the UK have evolved significantly over the past decades: osteopaths completed their training with a Diploma in Osteopathy (DO) until the end of the 1980s when the standard qualification shifted to a Bachelor of Science (BSc) degree; in the early 2000s, the profession saw another transition with the introduction of a Bachelor of Osteopathy (B.Ost.) degree18.This qualification remained the norm until late noughties, when many institutions began offering an integrated Master of Osteopathy (M.Ost.)19. These changes in degree structures were accompanied by substantial curricular modifications, particularly in the area of research methods20,21. Consequently, a skills disparity has emerged within the profession, with practitioners’ research competencies often correlating with their graduation period22. This variability in research training has implications for evidence-based practice and the profession’s overall research capacity16. The development of the UK Research Network hopes to address some of these issues through minimising the research-practice translational gap, upskilling the profession in research methods, and developing the evidence base in osteopathy.

This paper aims to provide data regarding the development of the NCOR Research Network, the first osteopathic Practice-Based Research Network in the UK, a useful infrastructure to support the development of research in osteopathy to better understand what is done in real-world practice29, by collecting data from clinicians (e.g. about their patients, their management strategies, or the number of sessions), from patients (e.g. using Patient Reported Outcome Measures or Patient Reported Experience Measures), or combining both patients’ and clinicians’ data27,30. A range of study designs can be employed, including observational studies, pragmatic clinical studies, and qualitative research12,31.

Methods

Recruitment

The NCOR Research Network is the first osteopathic PBRN in the UK. A series of events were held in the year prior to its launch22. These events had two aims: to ensure that the NCOR Research Network would be meaningful to osteopaths; and to make key stakeholders and osteopaths aware of the importance of PBRNs for the professions to maximise recruitment. Four one-day events and three online webinars were delivered between October 2022 and August 2023, an exhibition stand was set up at a major international conference near London in October 2023, two articles were published in the professional association’s magazine and e-newsletters, direct contact was made with osteopathic regional groups in the UK, and a live broadcast was recorded to an audience of around 800 clinicians. Invitations were also sent by email to all osteopaths on the GOsC database who agreed to be contacted for research purposes.

Questionnaire

A survey was used in this cross-sectional study to collect the information necessary to establish the research questions that could realistically be addressed through data collection using the PBRN. The questionnaire used in this study was not formally validated through psychometric testing. However, its development was informed by previously used surveys from established Practice-Based Research Networks (PBRNs) in osteopathy, including those in Australia and New Zealand13,23,24, as well as existing UK osteopathic datasets such as the Standardised Data Collection tool25 and Patient Reported Outcome Measures26. This approach ensured comparability of data across different research initiatives. Prior to initiating recruitment, qualitative work was conducted to explore key issues in depth22. This preliminary research helped identify pertinent topics for inclusion in the survey’s development. The methodological rigorous approach ensured both the integrity and coherence of data collection, while maximising the potential impact of findings for diverse stakeholders including practitioners, educators, and policy makers.

Similar surveys have been conducted with members of other PBRNs for the same purpose, and were used in the design of the methodology and survey for this study. Existing PBRNs were launched with a similar survey to provide data on their members. This enabled future sub-studies to target members’ preferences and settings. The questionnaire was divided into 4 sections: Sect. 1 contained qualifying questions to ensure that participants were eligible to take part in the survey (i.e. providing consent to take part, being registered with the General Osteopathic Council (GOsC), living and working in the UK). It also identified whether the osteopath had a clinical role and should complete Sects. 2 & 3. Section 2 contained questions relating to the nature of the clinical work that the osteopath undertook (e.g., geographical location of the clinics they work in and the number of patients that they typically see per week). Section 3 contained questions about the type of patients the osteopath typically sees and how they are managed (e.g., the symptoms their patients commonly present with and what sub-groups of patients are commonly seen e.g. age groups or activities or comorbidities). Section 4 contained demographic questions about the participant (e.g. length of time in practice and professional qualifications). See Supplementary Material 1 for more details on the content and structure of the questionnaire. The data were collected via an online self-reported questionnaire, using SmartSurvey© as an online platform.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and members of the public were not involved in this phase of setting up the NCOR Research Network. The reason for this is that this step was to recruit osteopaths to carry out further studies. This manuscript reports on the development of this research infrastructure. Future clinical studies will involve patients and the public at an early stage of project design to ensure that projects are meaningful to them and that research is done with patients / members of the public, not on them.

Protocol and ethics

The protocol for this project was registered on the Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HPWG4) before the analysis was conducted27. Ethical approval was received from the University College of Osteopathy Research Ethics Committee (#21122023). All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations. All participants were provided with detailed information about the study before deciding to take part, and informed consent was obtained from all participants when returning their completed questionnaire. The research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

Data were imported into Microsoft Excel™. Our study employed a two-stage approach to data management. At the questionnaire level, we included only fully completed questionnaires from participants who met all eligibility criteria. At the item level, all questions in the survey were configured as mandatory fields, requiring a response before participants could proceed. For sensitive demographic questions (e.g., gender, ethnicity), participants were provided with a ‘Prefer not to say’ option, which constitutes a valid response rather than missing data. This approach ensured complete data for all variables across all included participants. Descriptive statistics were used: dichotomous and categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations. The representativeness of the NCOR Research Network data was assessed by performing a chi-square test to compare its demographic characteristics to those of the broader population of GOsC-registered osteopaths.

Results

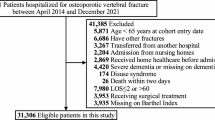

From approximately 5,500 registered osteopaths in the UK, 897 participants started the questionnaire (initial response rate of 16.3%), with 631 completing it fully (completion rate of 70.3%). After checking eligibility criteria, 570 participants were included in the NCOR Research Network (representing approximately 10.4% of all UK registered osteopaths). The reasons for exclusion were not being registered with the General Osteopathic Council (n = 37) or participants not consenting for their data to be collected or stored (n = 24).

Comparison with the GOsC registrant data revealed that the sample was not nationally representative of the UK osteopathic profession in terms of gender, age, ethnicity, and years in practice (ps < 0.005) (see supplementary material 2 - Table A).

Osteopaths’ characteristics

The median age bracket of the osteopaths was 50–59 (SD = 1.20), and 55% identified as women. They had seen patients as an osteopath for a median of 17 years (SD = 11.9). More than half of the osteopaths had a bachelor’s degree (53%), over a quarter an undergraduate master’s degree (26%), 20% a postgraduate master’s degree, and 4% a doctoral degree. The majority of their patient contact work was in private practice (71% as principals and 32% as associates), 3% worked in the NHS, and 9% were providing clinical supervision (see Table 1).

Osteopaths’ clinical work

Most participants were seeing patients between 20 and 29 (34%) or 30 to 39 hours (30%) per week, with the majority seeing 0 to 4 new patients (54%) and 32% seeing 20 to 29 follow up patients per week. 77% reported receiving referrals at least monthly, and the main sources were massage therapists (39%), other osteopaths (32%), GPs (29%), and health insurance companies (22%) (see Table 2).

The majority were seeing patients in one clinic (51%), but there was a range of the number of locations, with some participants seeing patients in up to 6 or more locations (1%). Most participants were working with other healthcare professionals in their clinics (80%), the five most frequent other professionals were osteopaths (79%), massage therapists (55%), acupuncturists (37%), physiotherapists (34%), and psychologists or counsellors (32%) (see supplementary material 2 - Table B).

Most participants had a specialist clinical interest (56%), the top five were: cranial osteopathy (40%), chronic / persistent pain (37%), paediatrics (4 to 18 years old) (32%), sports injuries (29%), and paediatrics (under the age of 4) (27%) (see Table 3).

Most participants reported referring patients for diagnostic imaging quarterly (38%) or monthly (38%). The main reason was for the identification of serious pathology (40%) or when patients were not responding to treatment (27%) (see Table 2).

Osteopaths’ patients’ characteristics

Adults 65 years of age or older were the sub-group of patients most seen by osteopaths on a regular basis (daily or weekly) (87%). People with sports-related injuries were reported as being seen regularly by 58% of osteopaths with only 2% never seeing this patient sub-group. A fifth to a third of the osteopaths regularly saw babies aged under 1 (27%), toddlers aged 1 to 3 years were seen regularly by 20% and children aged 4 to 17 years 21%, and 50%, 48% and 9% reported never seeing these patient sub-groups respectively. A quarter of participants saw pregnant women on a regular basis, with only 5% never seeing them. Professional sports people were seen regularly by 17% of the osteopaths, with 35% reporting never seeing this subgroup of patients (see Table 4).

Patients’ symptoms

Participants reported mostly seeing patients with musculoskeletal complaints: 71% reported that 75–100% of their patients consulted with MSK symptoms as their main complaint (see Table 5). Participants reported the frequency they were seeing patients (including new and follow-up) for different complaints. The only complaint that was most frequently seen on a daily basis was low back pain with or without radiculopathy (56%). Complaints that were mostly seen weekly were knee pain (57%), hip pain (57%) shoulder pain (54%), headaches (51%), mid or upper back pain (50%), and neck pain with or without radiculopathy (49%). Complaints that were mostly seen monthly were elbow pain (40%) and foot pain (35%). The complaint that was mostly seen quarterly was hand pain (30%). Two complaints were mostly never seen: non-musculoskeletal paediatric complaints (48%) and non- musculoskeletal adult complaints (31%) (see Table 6).

Osteopathic management

Participants reported the frequency they were using different techniques or approaches in patient management. The approaches that were mostly used daily were: Spinal articulation or mobilisation (79%), Soft tissue massage (78%), exercise recommendation (74%), Muscle Energy Technique (MET) or Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation (PNF) (57%), High Velocity Thrust (HVT) or spinal manipulation/adjustment (50%), General Osteopathic Treatment (GOT) or General Body Adjustment (GBA) (33%) and cranial osteopathy (32%). Several approaches were mostly reported as never being used by the majority of the participants: Intervertebral Differential Dynamics (IDD) therapy or Intermittent Sustained Spinal Traction (ISST) (89%), Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) or Electrical Muscle Stimulation (EMS) (84%), Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy (ESWT) (83%), laser therapy (85%), instrument assisted soft-tissue (78%), ultrasound (77%), and dry needling or acupuncture (54%). 74% reported never using any other approaches than the ones listed. Some approaches were variable in the frequency they were used: strain-counterstrain or facilitated positional release were used weekly by 26% of the participants whilst 25% never used them; neurodynamics or flossing were used weekly by 28% of participants whilst 33% never used them (see Table 7).

In terms of other strategies to support patient self-management, participants reported that they mostly discussed these approaches on a daily basis: general physical activity (not specific MSK exercise rehabilitation) (65%), stress management (45%), medication (including for pain/inflammation) (43%), occupational health and safety or ergonomics (42%), and diet or nutrition (36%). On a weekly basis: nutritional supplements (including vitamins, minerals, herbs) (30%), and smoking, drugs or alcohol cessation (27%). Infant feeding advice was never discussed by 50% of the participants, and other health promotion advice or education was never discussed by 37% of the participants (see Table 8).

The majority of the participants had positive views regarding evidence-based practice. Participants reported lacking research training, experience or skills beyond their undergraduate training; and lacking spare time for research related to osteopathic practice (see supplementary material 2 - Table C).

Discussion

The aim of this paper was to provide data regarding the development of the NCOR Research Network, the first osteopathic Practice-Based Research Network in the UK. Clinical practice reported by NCOR Research Network osteopaths demonstrates substantial alignment with current clinical guidelines. For instance, the criteria reported by osteopaths for referring patients for diagnostic imaging are consistent with international guidelines for musculoskeletal care28. Moreover, the incorporation of self-management strategies in treating musculoskeletal complaints reflects adherence to national guidance29,30. These practices suggest a growing trend towards evidence-informed care within the osteopathic profession. This shift is further corroborated by longitudinal data on practitioners’ attitudes. Between 2014 and 2020, there was an increase in the proportion of osteopaths who agreed or strongly agreed that evidence-based practice improves patient care, rising from 38 to 50%31,32. This trend indicates a gradual but significant change in the profession’s perspective on the value of evidence-based approaches. Future research endeavours could productively focus on exploring the impact of the NCOR Research Network on osteopaths’ sense of engagement with research and the ongoing evolution of attitudes towards evidence-informed practice. This could provide insights into the factors driving the profession’s increasing embrace of evidence-based methodologies and identify potential barriers or facilitators to this transition.

This is the first report including UK osteopaths’ qualifications in a research study. More than half of the osteopaths had a bachelor’s degree, nearly half had a master’s level degree and 4% a doctoral degree related to healthcare. This is a higher number than for osteopaths practising in Germany, Italy, Switzerland, and Belgium-Netherlands-Luxembourg, but lower than in Australia33. The percentage of osteopaths with a doctoral degree is higher than in other osteopathic PBRNs (e.g. 0.5% in ORION14). Despite the overall high academic qualifications of our osteopaths, the main challenges they reported facing regarding taking part in research were a lack of research skills, and a lack of time. This identifies a need to develop research training for NCOR Research Network osteopaths to facilitate their engagement with research and ensure a positive research culture.

NCOR Research Network osteopaths reported using a variety of manual therapy approaches that have previously been identified as commonly used by osteopaths33. They reported also discussing a range of health-related topics with their patients, including physical activity, stress management, medication, occupational health and safety or ergonomics, diet or nutrition, smoking, drugs or alcohol. These types of discussions are consistent with national initiatives for healthcare professionals such as Making Every Contact Count34, however, there is a need to assess the nature of these discussions and possibly to assess the usefulness of existing interventions to support clinicians treating MSK conditions.

Despite the lack of representativeness of the NCOR Research Network sample, the clinical data reported were consistent with data collected in the UK in 20191. The similar characteristics included the predominant subgroup of patients being 65 years or older, musculoskeletal complaints as the primary reason for consultation, and consistency in techniques and approaches implemented in patient management. The NCOR Research Network osteopaths reported more frequent use of general physical activity advice, stress management techniques, medication discussions, and diet and nutrition discussions compared to osteopaths in 2019. These differences may be attributed to either the lack of representativeness of the NCOR Research Network sample or potential shits in osteopathic practice over the past five years. Several aspects of osteopathic practice remain underexplored, highlighting a pressing need for additional data collection and analysis: including the decision-making process that leads patients to seek osteopathic care, or the factors influencing the discontinuation of osteopathic care. A well-designed system will be required to prioritise efficiency in data collection, as osteopaths have expressed concerns about time-consuming nature of participation in research. Striking a balance between comprehensive data gathering and minimising the burden on osteopaths will be crucial for future studies in this field.

Strengths and limitations

The survey was widely promoted to the osteopathic profession through various channels available in the UK. These included: the regulatory body (GOsC), the professional organisation (Institute of Osteopathy), professional publications, and face-to-face and online presentations to diverse groups. Prior to initiating recruitment, qualitative work was conducted to explore key issues in depth. This preliminary research helped identify pertinent topics for inclusion in the survey’s development.

The survey development was informed by similar surveys that had been used for other osteopathic PBRN set ups13, and by other osteopathic datasets in the UK, including PROMs26 and the Standardised Data Collection tool25, to allow comparability of data.

However, the sample in our study is not representative of the profession in the UK when compared to the GOsC registrant data. The majority of NCOR Research Network work with other healthcare professionals. This is different from a previous survey of osteopaths in the UK that found that 64% were working alone1, compared to 20% in our participants. This difference may be due to our sample not representing the profession or related to changes that may have happened since the above-mentioned survey data was collected in 2018. The self-selecting nature of the NCOR Research Network survey participants may have attracted those who are more inclined to want to work with others, given the ‘network’ focus of the survey. The recruitment strategy used different methods, including events in different parts of the UK, to promote the NCOR Research Network to as many of the profession as possible. Whilst the response rate was above the requirements for the setup of a PBRN, we may have to consider promoting NCOR Research Network to specific groups to help developing representativeness, particularly those who have been in practice for less than 10 years. Another limitation is that the survey data were self-reported by osteopaths, so the findings may be impacted by recall or social desirability biases.

Conclusion

The NCOR Research Network represents a paradigm-shifting advancement for osteopathic research in the UK, establishing the first formal practice-based research infrastructure for the profession. This novel framework has the potential to be the benchmark for years to come, fundamentally transforming how evidence is generated and implemented within osteopathic practice. Our findings reveal a community of practicing osteopaths primarily treating musculoskeletal complaints, with data serving as an essential baseline for future research initiatives.

The development of this innovative network creates substantial opportunities for collaboration between clinicians and researchers, potentially bridging the research-practice gap that has historically challenged the profession. The wide-ranging analysis presented here maps out a complex field and offers original insights that could greatly advance theory, policy, and practice within osteopathic healthcare.

Despite challenges of maintaining sustained participation, as evidenced by the time constraints and research skill limitations reported by participants, there is reason for optimism. The strong initial response from UK osteopaths, exceeding minimum requirements for establishing a PBRN, suggests the network can foster a rigorous, clinically relevant research culture reflecting the diversity of osteopathic practice throughout the UK.

Osteopaths in the UK who would like to join NCOR Research Network can find further information on https://ncor.org.uk/PBRN/.

Data availability

Data are presented in the tables of the manuscript. For any queries, please contact NCOR directly (info@ncor.org.uk).

References

Plunkett, A., Fawkes, C. & Carnes, D. Osteopathic practice in the united kingdom: A retrospective analysis of practice data. PLoS One. 17, e0270806 (2022).

General Osteopathic Council. Objective activity. General Osteopathic Council. (2024). https://cpd.osteopathy.org.uk/getting-started/objective-activity/ (accessed 18 July 2024).

Vaucher, P., Macdonald, R. J. D. & Carnes, D. The role of osteopathy in the Swiss primary health care system: a practice review. BMJ Open. 8, e023770 (2018).

Steel, A. et al. Impact of the workforce distribution on the viability of the osteopathic profession in australia: results from a National survey of registered osteopaths. Chiropr. Man. Th. 26 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-018-0204-0 (2018).

Bagagiolo, D., Rosa, D. & Borrelli, F. Efficacy and safety of osteopathic manipulative treatment: an overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 12, e053468 (2022).

Sénéquier, A. et al. Investigating the trustworthiness of randomised controlled trials in osteopathic research: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Clin. Epidemiol ;111788. (2025).

Morris, Z. S., Wooding, S. & Grant, J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: Understanding time lags in translational research. J. R Soc. Med. 104, 510–520 (2011).

Sherrington, C. et al. Ten years of evidence to guide physiotherapy interventions: physiotherapy evidence database (PEDro). Br. J. Sports Med. 44, 836–837 (2010).

Davis, M. M. et al. Integration of improvement and implementation science in practice-based research networks: A longitudinal, comparative case study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 36, 1503–1513 (2021).

Westfall, J. M. et al. Practice-based research networks: strategic opportunities to advance implementation research for health equity. Ethn. Dis. 29, 113–118 (2019).

Hall-Lipsy, E., Barraza, L. & Robertson, C. Practice-Based research networks and the mandate for real-world evidence. Am. J. Law Med. 44, 219–236 (2018).

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Register your network. AHRQ. (2022). https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/communities/pbrn/registry/register.html (accessed 1 July 2024).

Steel, A. et al. Introducing National osteopathy practice-based research networks in Australia and new zealand: an overview to inform future osteopathic research. Sci. Rep. 10, 846 (2020).

Adams, J. et al. A workforce survey of Australian osteopathy: analysis of a nationallyrepresentative sample of osteopaths from the osteopathy research and innovation network (ORION) project. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18, 1–7 (2018).

Degenhardt, B. F. et al. Preliminary findings on the use of osteopathic manipulative treatment: outcomes during the formation of the practice-based research network, Do-touch.net. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 114, 154–170 (2014).

Chalmers, S. et al. The value of allied health professional research engagement on healthcare performance: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 23, 766 (2023).

Gagliardi, A. R. et al. Integrated knowledge translation (IKT) in health care: a scoping review. Implement. Sci. 11, 38 (2016).

Becoming an osteopath. General Osteopathic Council. (2025). https://www.osteopathy.org.uk/training-and-registering/becoming-an-osteopath/ (accessed 6 May 2025).

University College of Osteopathy. Timeline of the UCO. University College of Osteopathy. (2018). https://www.uco.ac.uk/news/timeline-uco (accessed 15 August 2024).

MacMillan, A. et al. The extent and quality of evidence for osteopathic education: A scoping review. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 49, 100663 (2023).

Licciardone, J. C. Educating osteopaths to be researchers-what role should research methods and statistics have in an undergraduate curriculum. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 11, 62–68 (2008).

Bailey, D. et al. The development of the National Council for osteopathic Research - Research network (NCOR-RN): A qualitative focus group study of osteopaths’ views. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 55, 100742 (2025).

Lalji, R. et al. The Swiss chiropractic practice-based research network: a population-based cross-sectional study of chiropractic clinicians and primary care clinics to inform future musculoskeletal health care research. Res. Square (2022).

Adams, J. et al. A cross-sectional examination of the profile of chiropractors recruited to the Australian chiropractic research network (ACORN): a sustainable resource for future chiropractic research. BMJ Open. 7, e015830 (2017).

Fawkes, C. A. et al. Development of a data collection tool to profile osteopathic practice: use of a nominal group technique to enhance clinician involvement. Man. Ther. 19, 119–124 (2014).

Fawkes, C. & Carnes, D. Patient reported outcomes in a large cohort of patients receiving osteopathic care in the united Kingdom. PLoS One. 16, e0249719 (2021).

Bailey, D. NCOR Research Network members’ survey protocol. (2024).

Cuff, A. et al. Guidelines for the use of diagnostic imaging in musculoskeletal pain conditions affecting the lower back, knee and shoulder: A scoping review. Musculoskelet. Care. 18, 546–554 (2020).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic Pain (primary and secondary) in Over 16s: Assessment of all Chronic Pain and Management of Chronic Primary Pain (NICE, 2021).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. (2016). (2023).

McGivern, G. et al. Exploring and explaining the dynamics of osteopathic regulation, professionalism and compliance with standards in practice. Gen. Osteopath. Council (2015).

McGivern, G. et al. 2020 Osteopathic Regulation Survey: Report To the General Osteopathic Council (Warwick Business School, 2020).

Ellwood, J. & Carnes, D. An international profile of the practice of osteopaths: A systematic review of surveys. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 40, 14–21 (2021).

Parchment, A. et al. How useful is the making every contact count healthy conversation skills approach for supporting people with musculoskeletal conditions? Z. Gesundh Wiss. 30, 2389–2405 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof Alice Kongsted (University of Southern Denmark) and Dr Amie Steel (University of Technology Sydney) for their generous support by sharing their experience and expertise with setting up Practice-Based Research Networks.

Funding

This project received funding from the Osteopathic Foundation. The funder did not have any specific role in the conceptualisation, design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JDR, CF, and DB conceptualised and designed the study. DB registered the protocol. DB led the data collection. DB and JDR conducted the data analysis. JDR drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors (JDR, CF, and DB) critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, provided substantial input to subsequent drafts, and approved the final version. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The Osteopathic Foundation (Charity that funded this project) is a stakeholder of the National Council for Osteopathic Research. JDR and CF have received grants from the Osteopathic Foundation. JDR provides research expertise to the Osteopathic Foundation for grant application review. JDR, CF and DB receive salaries from the National Council for Osteopathic Research (NCOR) hosted by Health Sciences University (HSU). JDR and DB are registrant members of the General Osteopathic Council (GOsC).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was received from the University College of Osteopathy Research Ethics Committee (#21122023), and all participants provided consent to take part in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Draper-Rodi, J., Fawkes, C. & Bailey, D. Development of a national osteopathic Practice-Based Research Network (PBRN): the NCOR Research Network. Sci Rep 15, 26396 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11527-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11527-4