Abstract

This study investigated the swallowing dynamics of jelly, thickened liquid, and thin liquid in selected stroke patients who exhibited near-normal swallowing function with screening tests. Videofluoroscopic examination compared the pharyngeal transit time (PTT), pharyngeal delay time (PDT), and laryngeal elevation delay time (LEDT). Of 175 patients (104 men, 71 women; mean age: 68.6 ± 12.0 years) evaluated, 24 (13.7%) experienced aspiration, significantly prolonging LEDT in swallowing thin liquid. PTT did not differ in swallowing jelly, thickened liquid, or thin liquid among the patients who did not aspirate. However, in two-phase analysis of PTT, performed before and after the jelly passed the epiglottis, the former was significantly prolonged, whereas the latter was significantly shortened. PDT was significantly longer with jelly than with thickened and thin liquids. LEDT was significantly longer in swallowing thin liquids. Apparently, the thin liquid reached the pyriform sinus before maximum laryngeal elevation, posing a risk of laryngeal penetration and aspiration during swallowing. A thicker liquid prolonged the time taken to reach the pyriform sinus, reducing aspiration risk. Moreover, oropharyngeal passage of jelly took longer, triggering the swallowing reflex around the vallecula and allowing the jelly to pass through the hypopharynx after laryngeal closure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Providing appropriate food forms is crucial to patients with reduced mastication or swallowing function to prevent malnutrition and aspiration1. Foods modified for dysphagia are food forms especially formulated for patients with reduced mastication and swallowing functions in terms of form, thickness, and flexibility to match patients’ swallowing abilities. The International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative (IDDSI) Framework, which provides global standards, was published in 20172, whereas the earlier Japanese Dysphagia Diet domestic framework was developed in 2013 and has since been widely used in Japan3.

Although the Japanese Dysphagia Diet 2013 was revised in 2021 (JDD2021)4, the core principles remain unchanged. This classification includes five stages (codes 0–4) for modified foods and three for modified liquids. The thickening standards align closely with those used internationally5. A unique feature of JDD2021 is code 0, which is the swallowing training diet designed for early-stage swallowing rehabilitation. It further distinguishes between 0j (“j” for jelly) and 0t (“t” for thickened) to accommodate a wider range of adult patients with mid-stage dysphagia. Code 0j refers to a homogeneous, less sticky, cohesive, softer, and low-shrinkage jelly that can be sliced easily. Specifically, it can be scooped with a thin, flat spoon into a mass of 2 cm (length) × 2 cm (width) × 5 mm (thickness) and be directly swallowed without crushing or masticating. It must also be easily mechanically suctioned when residues remain in the mouth6. This type of jelly is now commercially available for rehydration7 and medication8. Similarly, code 0t refers to a moderately thick liquid (150–300 mPa viscosity) with a consistency that flows slowly down a tilted spoon. This thickened liquid is commonly used worldwide for dysphagia therapy. However, some foreign countries consider jelly unsuitable for patients with dysphagia.

Although the JDD2021 is widely used in Japan, no consensus has been reached on the use of 0j and 0t. Current guidance recommends 0t over 0j only when the jelly is aspirated or when it dissolves in the mouth. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine the swallowing characteristics of code 0j, which is less commonly used in dysphagia rehabilitation outside Japan, compared to other food forms, and to scientifically validate whether using jelly in swallowing therapy is appropriate.

Methods

This study was approved by the Suiseikai Kajikawa Hospital Ethics Committee (Approval no. 2016-1) and the Hiroshima University Graduate School of Biomedical and Health Sciences Ethics Committee (Approval no. E-1151). All procedures were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians.

We enrolled consecutive patients with acute stroke who were admitted to the Suiseikai Kajikawa Hospital between August 1, 2016, and March 31, 20209,10. However, since time analysis was only incorporated after the results of Takeda et al.9 were published, the subjects enrolled in this study were those admitted between January 11, 2018, and March 31, 2020.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were the same as those used by Nakamori et al.10. The inclusion criteria were patients with first-time stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) admitted within 1 week of onset, were aged ≥ 20 years, and consented to participate in the study (if the patient was unable to provide his/her consent, it was sought from relatives). We excluded patients with a history of stroke or dementia (using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision), those with altered mental state after severe stroke (if the best Glasgow Coma Scale eye response score ≤ 3) and those who had not resumed oral intake. Patients who had more than 4 points on the modified water swallow test (MWST) and were able to swallow ≥ 3 times within 30 s on the Repetitive Saliva Swallowing Test (RSST) were considered eligible11. To further minimize risk, we included those who exhibited the lowest possible risk of dysphagia with a score ≥ 95 on the Modified Mann Assessment of Swallowing Ability (MMASA)12. Because VF involves radiation exposure and is unsuitable for healthy individuals, these criteria were further used to select patients with stroke showing relatively normal swallowing function.

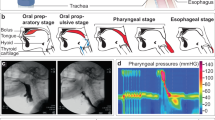

All patients underwent VF within 14 days of the stroke event. Three food forms with different consistencies were tested: 3 mL thin liquid, 3 mL thick liquid containing 3% thickening agent (defined as extremely thick), and 3 g jelly, each containing 50% iodine contrast medium (Oypalomin 370, Fuji Pharma Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Neo High Toromeal (Food Care Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used as the thickening agent, while Aqua Jelly Powder (Food Care Co., Ltd.) was used to prepare the jelly. The tester placed each food form on the patient’s tongue, who were then instructed to swallow the food in one motion. The tests were conducted once or twice for each food form in a fixed sequence: thin liquid, thickened liquid, and jelly. The best replicate based on inter-examiner discussion was used for analysis.

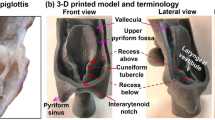

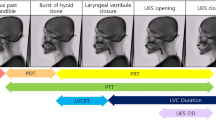

X-ray examinations were conducted with a Philips BV Pulsera X-ray system (Amsterdam, Netherlands) at 30 frames per second, and the data were recorded on a DVD. With the patients in a seated position, images were captured of lateral views encompassing anatomical landmarks anteriorly to the lips, posteriorly to the pharynx wall, superiorly to the nasal cavity, and inferiorly to the upper esophageal sphincter. Two experienced dentists (TN and MY) who specialized in VF evaluation and were blinded to the patients’ clinical data, evaluated the presence of natural light-visible aspiration and quantitatively analyzed indicators commonly used to assess aspiration risk on VF. These parameters, which are useful in assessing aspiration risk by VF, included pharyngeal delay time (PDT), defined as the interval from when the bolus head reached the mandibular ramus–tongue base junction to the onset of laryngeal elevation13,14; pharyngeal transit time (PTT), the interval from when the bolus head reached the mandibular ramus–tongue base junction until the bolus tail passed the cricopharyngeal region or pharyngoesophageal segment13,15; and laryngeal elevation delay time (LEDT), the interval from bolus arrival at the pyriform sinus to the onset of maximum laryngeal elevation16. Furthermore, to distinguish between bolus passage in the middle pharynx and hypopharynx, PTT was divided into two phases: oropharyngeal transit time (oPTT), measuring the time to bolus epiglottic passage, and hypopharyngeal transit time (hPTT), the interval from bolus epiglottic passage to cricopharyngeal transit.

Statistical analysis

The VF characteristics of patients who aspirated during thin liquid swallowing were compared with those who did not. Basic information and VF time measurements were compared using the χ2 test and Mann–Whitney U test, respectively. Among those who did not aspirate during thin liquid swallowing, PTT, PDT, LEDT, oPTT, and hPTT of jelly, thickened liquid, and thin liquid during VF were compared using the Friedman test and Scheffe post hoc test. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS ver. 23 (IBM, Tokyo, Japan), and results were reported with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Table 1 presents patient data on aspiration during thin liquid swallowing. Out of 175 patients (104 men and 71 women, median age: 70 years) included in the study, 24 (13.7%) experienced aspiration. Although no significant differences in age or underlying diseases were observed between those who aspirated when swallowing thin liquid and those who did not, VF time analysis revealed that LEDT was significantly prolonged in those who aspirated (p < 0.05). Half of those who aspirated had an LEDT > 0.35 s, which is the cutoff value12.

Swallowing dynamics were quantitatively compared for each food form, excluding patients who aspirated during thin liquid swallowing (Table 2). All three food forms were swallowed all at once, as instructed, and no residue remained after swallowing. The results indicated no significant difference in PTT among the three food forms. However, oPTT was significantly prolonged and hPTT significantly shortened in swallowing jelly (p < 0.05). Furthermore, PDT was significantly delayed in swallowing jelly compared with thickened and thin liquid. In contrast, LEDT was significantly delayed during swallowing of thin liquid compared with jelly and thickened liquid (p < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we compared the swallowing dynamics of jelly and thickened liquid, the food forms most commonly used for dysphagia therapy in Japan, in stroke patients who were unlikely to have dysphagia based on the screening test. Normally, this study would have been conducted on healthy elderly subjects, but due to the radiation exposure requirement17, only selected stroke patients who exhibited near-normal swallowing function with screening tests. No gold standard has been established for dysphagia screening; thus, a multimodal assessment is desirable18. In this study, we employed a combination of MWST and RSST, which have been well-validated and are commonly used in Japan11. Moreover, the MMASA was incorporated to identify patients with low aspiration risk19. Despite this multimodal approach, approximately 10% of aspirations were missed during the screening tests. Similarly, in the present study, aspiration during thin liquid swallowing was observed in 13.7% of the patients. Patients who aspirated exhibited significantly prolonged LEDT, which indicates reduced sensitivity to peripheral nerve input16. This aligns with the study by Jafari et al.20, which reported that afferent signals from the superior laryngeal nerve help facilitate laryngeal closure during swallowing. These results imply that reduced pharyngolaryngeal sensory feedback during swallowing may cause aspiration when swallowing thin liquids. This study compared the swallowing dynamics of jelly and thickened water in patients with near-normal swallowing function, excluding those who aspirated thin liquids since they were considered to have dysphagia.

We conducted VF temporal analysis of the swallowing dynamics, specifically the pharyngeal phase of swallowing, using jelly, thickened liquid, and thin liquid. All food forms demonstrated a PTT of approximately 1 s, which is comparable to previous findings on healthy elderly subjects10,21 and contrasts with the prolonged PTT observed in patients with dysphagia22. However, pharyngeal passage patterns differed among the food forms. Significant differences in LEDT were observed between thin and thickened liquid, indicating that the thickening agent could potentially reduce aspiration risk by slightly delaying bolus arrival at the piriform sinus. The jelly induced a swallowing reflex slightly deeper than the faucial isthmus, specifically upon bolus arrival at the epiglottis. This indicates that the jelly settled briefly in the vallecula before eliciting the swallowing reflex. These findings provide empirical evidence of existing clinical practices, indicating that jelly should be avoided in cases where premature pharyngeal entry may occur, such as in cases of impaired consciousness or attention disorders.

This study has some limitations. First, we did not evaluate patients who aspirated with jelly or thickened liquid. Therefore, we could not provide definitive comparisons of the swallowing dynamics of patients who actually aspirated with these food forms. Further confirmatory studies are thus needed. Second, the study did not examine the movement and range of motion of the hyoid bone and larynx, which may be involved in aspiration, because our screening test may have excluded individuals with such swallowing impairments. Furthermore, although the IDDSI is currently being promoted as an international standard, its classification system is based on clinical practice and must be objectively investigated to determine their effects on swallowing dynamics and function. Nevertheless, this study provides empirical support for the JDD2021 diet selection criteria and establishes a framework for selecting food forms.

Conclusion

This study reports important findings regarding swallowing dynamics. First, thin liquids reach the piriform sinus before maximal laryngeal elevation, posing a risk of penetration and aspiration before complete laryngeal closure. Second, thickening agents may reduce aspiration risk by slightly delaying bolus arrival at the piriform sinus. Third, jelly may reduce aspiration risk by delaying oropharyngeal passage, triggering the swallowing reflex in the epiglottis, and preventing hypopharyngeal passage after complete laryngeal closure. These findings provide scientific validation of existing clinical practices and highlight the importance of tailoring food consistency to swallowing function in patients.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Steele, C. M. et al. The influence of food texture and liquid consistency modification on swallowing physiology and function: A systematic review. Dysphagia 30, 2–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-014-9578-x (2015).

Cichero, J. A. et al. Development of international terminology and definitions for texture-modified foods and thickened fluids used in dysphagia management: The IDDSI framework. Dysphagia 32, 293–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-016-9758-y (2017).

The Dysphagia Diet Committee of the Japanese Society of Dysphagia Rehabilitation. The Japanese dysphagia diet 2013. Jpn J. Dysphagia Rehabil. 17, 255–267 (2013).

The Dysphagia Diet Committee of the Japanese Society of Dysphagia Rehabilitation. The Japanese dysphagia diet 2021. Jpn J. Dysphagia Rehabil. 25, 135–149 (2021).

Watanabe, E. et al. The criteria of thickened liquid for dysphagia management in Japan. Dysphagia 33, 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-017-9827-x (2018).

Aii, S. et al. Sliced jelly whole swallowing reduces deglutition risk: A novel feeding method for patients with dysphagia. Dysphagia 39, 940–947. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-024-10674-6 (2024).

Morita, A., Horiuchi, A., Horiuchi, I. & Takada, H. Effectiveness of water jelly ingestion for both rehabilitation and prevention of aspiration pneumonia in elderly patients with moderate to severe dysphagia. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 56, e109–e113. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000001493 (2022).

Sharpe, L. A., Daily, A. M., Horava, S. D. & Peppas, N. A. Therapeutic applications of hydrogels in oral drug delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 11, 901–915. https://doi.org/10.1517/17425247.2014.902047 (2014).

Takeda, C. et al. Delayed swallowing reflex is overlooked in swallowing screening among acute stroke patients. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 29, 105303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105303 (2020).

Nakamori, M. et al. Association between stroke lesions and videofluoroscopic findings in acute stroke patients. J. Neurol. 268, 1025–1035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-10244-4 (2021).

Watanabe, S. et al. Reconsideration of three screening tests for dysphagia in patients with cerebrovascular disease performed by non-expert examiners. Odontology 108, 117–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10266-019-00431-9 (2020).

Antonios, N. et al. Analysis of a physician tool for evaluating dysphagia on an inpatient stroke unit: The modified Mann assessment of swallowing ability. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 19, 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2009.03.007 (2010).

Yoshikawa, M. et al. Aspects of swallowing in healthy dentate elderly persons older than 80 years. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 60, 506–509. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/60.4.506 (2005).

Hino, H. et al. Effect of bolus property on swallowing dynamics in patients with dysphagia. J. Oral Rehabil. 51, 1422–1432. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.13709 (2024).

Rugiu, M. G. Role of videofluoroscopy in evaluation of neurologic dysphagia. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 27, 306–316 (2007).

Miyaji, H. et al. Videofluoroscopic assessment of pharyngeal stage delay reflects pathophysiology after brain infarction. Laryngoscope 122, 2793–2799. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.23588 (2012).

Hong, J. Y., Hwang, N. K., Lee, G., Park, J. S. & Jung, Y. J. Radiation safety in videofluoroscopic swallowing study: Systematic review. Dysphagia 36, 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-020-10112-3 (2021).

Boaden, E. et al. Screening for aspiration risk associated with dysphagia in acute stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 10, CD012679. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012679.pub2 (2021).

Panjikaran, N. D., Iyer, R., Sudevan, R. & Bhaskaran, R. Utility of modified Mann assessment of swallowing ability (MMASA) in predicting aspiration risk and safe swallow in stroke patients. J. Family Med. Prim. Care. 11, 5123–5128. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1628_21 (2022).

Jafari, S., Prince, R. A., Kim, D. Y. & Paydarfar, D. Sensory regulation of swallowing and airway protection: A role for the internal superior laryngeal nerve in humans. J. Physiol. 550, 287–304. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2003.039966 (2003).

Nishikubo, K. et al. Quantitative evaluation of age-related alteration of swallowing function: Videofluoroscopic and manometric studies. Auris Nasus Larynx. 42, 134–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2014.07.002 (2015).

Ko, J. Y. et al. Predictors of aspiration pneumonia in the elderly with swallowing dysfunction: Videofluoroscopic swallowing study. Ann. Rehabil Med. 45, 99–107. https://doi.org/10.5535/arm.20180 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Emeritus Keiji Tanimoto of Hiroshima University for his suggestions. We also appreciate Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English translation support.

Funding

This study was supported by research grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (Grant number 18K10746 and 19K10207).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. Yoshikawa: data acquisition, data interpretation, and manuscript drafting. J. Kayashita: study design, data acquisition, and data interpretation.M. Nakamori: study design, data acquisition, and critical review.T. Nagasaki: data analysis and data interpretation.S. Masuda: study design, data interpretation, and critical review.M. Yoshida: study design, data analysis, and manuscript drafting.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committees, as well as the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoshikawa, M., Kayashita, J., Nakamori, M. et al. Comparison of swallowing dynamics between jelly and thickened liquid commonly used for swallowing training in Japan. Sci Rep 15, 26299 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11604-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11604-8