Abstract

Lisfranc injury is a complex trauma involving the midfoot joint, and treatment options range from conservative management to surgical intervention. Elastic fixation, an innovative surgical technique, has garnered attention for its ability to preserve the foot’s biomechanical properties. However, the influence of pretension on the efficacy of elastic fixation remains unclear. This study aims to use three - dimensional (3D) finite element analysis (FEA) to examine the biomechanics of the Lisfranc joint under different pretension fixation states. It seeks to determine the optimal pretension for achieving the same biomechanical stability as normal ligaments. This will provide theoretical support for elastic fixation in treating Lisfranc injuries. The study analyzed stress distribution, von Mises stress, and displacement under different pretensions to assess the biomechanical stability of elastic fixation. Results showed that varying pretension levels differentially affected Lisfranc joint biomechanics. Specifically, increased pretension correlated with greater medial cuneiform-second metatarsal (MC1-MT2) joint space displacement and higher stress on the MC1, MT2, titanium plate, and tarsometatarsal joint cartilage. Nonetheless, each pretension level exhibited a unique stress distribution pattern. At 70 N of pretension, elastic fixation achieved biomechanical stability comparable to that of the normal foot model. This study demonstrates that elastic fixation can effectively restrict abnormal movements in the injured Lisfranc joint and identifies the optimal pretension for proper fixation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lisfranc injury, or tarsometatarsal joint complex injury, is a serious midfoot condition involving ligament disruption, fractures, or joint dislocation1,2. Without timely and appropriate treatment, it can lead to complications such as malunion, chronic pain, and midfoot arthritis3. The incidence of Lisfranc injuries has been increasing, particularly due to a rise in traffic accidents4. Currently, early diagnosis, anatomical reduction, and stable fixation are widely accepted as key principles for effective management5,6.Treatment options range from conservative approaches to surgical interventions. Conservative treatment—such as casting or bracing—is typically reserved for stable injuries with minimal displacement, like Myerson type A and B1 injuries7. In contrast, unstable injuries (e.g., Myerson type B2, C1, and C2), characterized by displacement ≥ 2 mm or a tarsometatarsal angle ≥ 15°, generally require surgical fixation8. Although techniques such as screw fixation, mini-plate fixation, and K-wire fixation are commonly used, no consensus exists on the optimal surgical method9.

Elastic fixation has emerged as a novel technique that aims to preserve the foot’s physiological biomechanics while providing stability10. One crucial factor influencing the success of elastic fixation is the pretension applied during surgery11. However, current research on this method has largely focused on cadaveric studies evaluating general efficacy, with limited investigation into how different pretension levels affect fixation outcomes12,13,14,15,16. Moreover, cadaver studies require large sample sizes and are often limited by tissue degradation during repeated testing, which may compromise data accuracy and increase costs.

Finite element analysis (FEA) offers a non-invasive, reproducible, and highly controllable alternative to cadaver experiments. It allows for precise simulation of biomechanical conditions and stress distribution, making it particularly suitable for studying the effects of surgical variables such as pretension. Despite these advantages, the specific impact of pretension in elastic fixation of Lisfranc injuries has not been thoroughly examined through FEA.

Therefore, this study employs FEA to investigate the biomechanical effects of varying pretension levels in elastic fixation for Lisfranc injuries. By identifying the optimal pretension, we aim to improve fixation stability and provide a quantitative basis to guide surgical practice.

Materials and methods

Geometric design

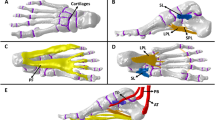

A 3D foot model was reconstructed using normal individuals’ CT scans (30-year- old, male,76 kg, 1.75 m, no history of foot trauma, tumors, or anatomical abnormalities) from the radiology department’s CT database. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the owner of the selected CT data consented to the use of his CT data for the study and signed an informed consent form. All experimental protocols were approved by the affiliated tumor hospital of Xinjiang Medical University.The foot and ankle were kept in a neutral position during the CT scan (voltage 120 kV, current intensity 240 mA, scanning layer thickness 0.600 mm). The CT data was saved in DICOM format. The foot and ankle data were imported into Mimics21.0 (Materialise, Belgium) software, and 3D surface geometry reconstruction of the bones, including the tibia, fibula, and foot and ankle, was performed using threshold segmentation, region growing, and manual erasure. Based on CT imaging measurements and estimates, cortical and cancellous bone segmentation was performed using a CT - value threshold method (cortical bone threshold: 1200–3000 HU, cancellous bone: 200–1200 HU). According to the measurements and literature references, the cortical bone thickness was set at 1 mm17with the remaining parts considered as cancellous bone. The STL files were then imported into Geomagic Wrap (Geomagic Company, USA) for reverse engineering. Corrections were made in Geomagic Wrap for the presence of pegs, corners, and small holes before fitting to the NURBS surfaces (Fig. 1a, b).

Overview of process steps. (a) Construct 3D skeletal model by segmenting CT images in Mimics software. (b) Construct cartilage and ligament model. (c) Apply boundary conditions and loading to the model (d) Volunteer plantar pressure analysis.(e) Volunteer plantar pressure analysis diagram. (f) Plantar stress distribution in the finite element model of this study.(g) Plantar stress distribution in Tao’s finite element model.

Material property assignment

HyperMesh software was used to mesh the bones, cartilage, and soft tissues using tetrahedral grid cells with mesh sizes of 1 mm for cortical bone, 1 mm for cancellous bone, and 2 mm for peripheral soft tissues. A convergence check was performed on the finite element model’s discretization until the calculated stress deviation was less than 5% (Fig. 2). The final model consisted of 458,721 nodes and 2,794,523 elements. After mesh generation in HyperMesh, the mesh model was exported to ANSYS Mechanical APDL for static analysis. A linear static analysis module was used to solve the structural response under static loads. All bones, cartilages, ligaments, and base plates were assumed to be linearly elastic materials with continuity, full elasticity, homogeneity, and isotropy. The base plate material was modeled as a rigid horizontal plate with a large Young’s modulus to simulate the ground. The soft tissue parameters accounted for the combined effects of the skin, subcutaneous fat, and fascia. The skin was modeled as an elastic material to better simulate the entire foot anatomy, the plantar loading conditions, and the frictional interface with the ground. This approach not only provides cushioning for the underlying bones but also dampens vibrations between contact surfaces, thereby promoting model convergence. Given that incompressible hyperelastic materials would significantly increase computational time, and considering that our model employed a linear static analysis module, we relied on prior studies18,19 and the small deformation assumption. Consequently, we set the elastic modulus of the soft tissues to 1.15 MPa and the Poisson’s ratio to 0.49. The material properties were obtained from the literature20,21,22 (Table 1).

Boundary conditions and loading definition

The coefficient of friction of the plantar contact with the rigid ground was set to 0.6. The subject weighed 76 kg, and in the standing phase, the right foot carried half of the body weight (380 N), and a load of 380 N was applied vertically upward through the rigid ground to simulate the plantar reaction force in balanced standing, with the tibia, fibula, and the upper surface of the soft tissues completely fixed in the constraints. In balanced stance, the Achilles tendon force is approximately 50% of the force applied to the foot17so a further vertical upward force of 190 N was applied to the Achilles tendon (Fig. 1c).

Validation

To verify the reliability of the finite element model, we used a plantar pressure measurement system to analyze the plantar pressure of volunteer who participated in the initial CT scanning (Fig. 1d), obtained plantar pressure distribution map (Fig. 1e), and loaded the finite element model based on the weight applied to one foot of the volunteer. The plantar stress of the model in this study aligns with the actual measured plantar stress of volunteers: the peak plantar pressure of volunteers was 0.234 MPa, while the model in this study showed 0.239 Mpa (Fig. 1f), the error is approximately 2%. Both were located at the center of the heel. The model validation was effective.

Boundary settings, load settings, and the size of the finite element model vary from study to study, in comparison with the model, the focus is on the comparison of stress distribution trends. We compared our plantar stress distribution cloud maps and FEA data with those from Tao’s finite element study14 (Fig. 1g). In the standing position, the peak plantar pressures in different regions showed good consistency. The peak pressure regions were consistent, both located under the second metatarsal head23, validating the finite element model’s effectiveness.

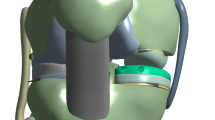

The establishment of the injured model

The injury was simulated as a Type D2 isolated ligamentous injury according to the Hardcastle & Myerson classification (Fig. 3). Ligaments (Dorsal metatarsal ligament、Lisfranc ligament、Plantar ligament) were removed within the model to simulate a Lisfranc ligamentous complex injury model24,25. Elastic fixation was then simulated, and pretension forces ranging from 0 N to 100 N were applied at both ends of the titanium plate. To facilitate finite element calculations, the model was simplified by fitting the titanium plate to the bone and setting them as co-nodal contacts. Two points were selected at the center of the plate, which were then paired and correspondingly connected to establish beam elements. Pretension forces were applied to simulate the traction line’s binding force on the plate and bone, with a diameter of 0.3 mm used to model the traction line. Point IDs were: 1,062,815 and 1,063,126 corresponding, and 1,062,946 and 1,063,243 corresponding. Beam elements were established through the IDs of the aforementioned points, material properties were assigned, and pretension forces were applied through coding (Fig. 4). All models were imported into Hyperworks 2019 software (Altair, USA) in IGES format. Frictionless face-to-face contact was used to represent the relative articular motion between layers of articular cartilage for frictionless sliding between the bones, and the ligaments were modeled using rod units that can only be stretched and not compressed based on anatomical information on the Digital Anatomy Platform and the Human Atlas. These ligaments were manually positioned and added to the model based on relevant anatomical landmarks.

Results

Through finite element analysis, we obtained the stress distribution in the tarsometatarsal joint cartilage, bones, and titanium plates, as well as the displacement of the MC1-MT2 joint space under 11 different pretension fixation conditions.

Von mises stress distribution in cartilage

The stress distribution of the cartilage in the tarsometatarsal joint can be seen in Figs. 5 and 6.

MC1 exhibits the largest stress increase, especially between 50 N and 100 N, significantly surpassing other bones. Intermediate cuneiform (MC2) and the cuboid show intermediate increases, while lateral cuneiform (MC3) has the smallest increase. The stress in all bones rises with increasing pretension, indicating that pretension significantly affects the stress distribution in articular cartilage. (Fig. 7). Stress of MC1 significantly increases with the rise of pretension, growing by 276.7% at 100 N compared to 0 N. The stress growth is particularly pronounced between 50 N and 100 N. Stress of MC2 gradually increases with rising pretension, with a 59.3% increase at 100 N compared to 0 N. The growth trend is relatively mild, but the increase becomes more pronounced at higher pretensions. Stress of MC3 progressively increases with increasing pretension, rising by 28.5% at 100 N compared to 0 N. The growth magnitude is relatively small. Stress of cuboid gradually increases with rising pretension, increasing by 37.2% at 100 N compared to 0 N. The growth trend is similar to that of MC3 but with a slightly higher increase at higher pretensions. MT1 and the second metatarsal (MT2) show the most significant stress increases with rising pretension, particularly MT1.The third metatarsal (MT3) exhibits the least stress change, even decreasing slightly in some cases. The fourth metatarsal (MT4) and the fifth metatarsal (MT5) show smaller stress increases, yet still rise with pretension (Fig. 8). Von Mises stress of MT1 increases significantly with pretension, up 167.4% at 100 N vs. 0 N. Stress of MT2 rises considerably, with a 81.1% increase at 100 N versus 0 N. Stress of MT3 changes minimally, even decreasing slightly (by ~ 3.7%) at some pretensions (10–100 N). Stress of MT4 rises gradually with pretension, increasing 20.7% at 100 N versus 0 N. Stress of MT5 increases moderately, up 17.7% at 100 N versus 0 N (Table 2). The findings indicate that as pretension increases, stress on nearly all cartilage increases to varying degrees. The cartilage at MC1/MT1 and MT2 exhibits larger stress changes and is at higher risk of damage. This indicates these cartilage areas are more prone to damage and have a higher chance of developing postoperative traumatic arthritis.

Von mises stress distribution in bones and titanium plates

The stress distribution of bones and titanium plates can be seen in Figs. 9 and 10. Both MC1 and the titanium plate attachment site show significant stress increases with rising pretension, particularly between 50 N and 100 N. The percentage changes in stress are similar, though increases at the titanium plate attachment site are slightly higher than those of MC1 (Fig. 11). MC1 von Mises stress increases significantly with rising pretension, up 304.0% at 100 N versus 0 N. Stress growth is especially pronounced between 50 N and 100 N. Von Mises stress of Titanium plate attachment site also increases significantly with rising pretension, up 305.1% at 100 N versus 0 N. The growth trend resembles that of MC1 but with slightly higher increases. Both MT2 and MT2 dry show significant stress increases with rising pretension, especially at higher levels. The titanium plate attachment site exhibits the largest stress increase, particularly between 50 N and 100 N, surpassing both MT2 and MT2 dry (Fig. 12). MT2 von Mises stress increases significantly with rising pretension, up 109.0% at 100 N versus 0 N. Stress growth is especially pronounced between 50 N and 100 N. Von Mises stress of MT2 dry also increases significantly with rising pretension, up 103.3% at 100 N versus 0 N. The growth trend resembles that of MT2 but with slightly lower increases at higher pretensions. Von Mises stress of Titanium plate attachment site increases significantly with rising pretension, up 161.1% at 100 N versus 0 N. The increase is particularly pronounced and higher than MT2 and MT2 dry between 50 N and 100 N. Stress at the MT2 titanium plate shows stable and gradual increases with rising pretension. At the MC1 site, stress slightly decreases at low pretensions but significantly increases at higher ones. Both sites see greater stress increases at higher pretensions (60–100 N), with MT2 showing slightly higher increases than MC1(Fig. 13). Von Mises stress at the titanium plate near MT2 gradually increases with rising pretension, up 20.4% at 100 N versus 0 N, with a mild growth trend and higher increases at higher pretensions (60–100 N). Von Mises stress at the titanium plate near MC1 slightly decreases at low pretensions (10–30 N) but increases afterward, up 16.3% at 100 N versus 0 N (Table 3). The findings indicate that stress is concentrated in MCI, matching cartilage stress distribution and making it more prone to injury. However, there’s less need to worry about bone damage at the titanium plate attachment site. The stress on MT2 changes slowly, suggesting a lower risk of bone damage. The titanium plate on the metatarsal side endures greater stress than the MC1 one, making it more prone to damage.

Model displacement

Through finite element analysis, under different pretension conditions, when the pretension was set to 70 N, the displacement of the MC1-MT2 joint space deviates from the normal model by 0.4%, suggesting that elastic fixation achieved biomechanical stability similar to the normal model (Fig. 14). The injured model shows a much greater displacement distance than the normal model, indicating a significant drop in joint stability post-injury. In the pretension-fixed models, the displacement distance decreases with increasing pretension, suggesting that pretension helps restore joint stability. At 70 N of pretension, the displacement distance approaches that of the normal model.

Between 80 N and 100 N of pretension, the displacement distance falls below that of the normal model, implying excessive pretension may cause overconstraint. (Table 4).

Discussion

This study developed finite element models of a normal foot and a Lisfranc ligament complex injury to evaluate the biomechanical effects of varying pretension levels in elastic fixation. The results showed that pretension significantly affects joint space displacement and stress distribution in the tarsometatarsal complex, particularly in the medial cuneiform (MC1), second metatarsal (MT2), and titanium plate.

A pretension of 70 N produced joint displacement closest to that of the normal model, indicating sufficient mechanical stability while preserving physiological micromotion. This is consistent with prior research suggesting that elastic fixation, when appropriately tensioned, can replicate the stability of screw fixation while promoting more favorable conditions for ligament healing27,28. In contrast, excessive or insufficient pretension may result in instability or stress overloading—supporting the idea that controlled micromotion is essential for optimal recovery29,30,31.

Previous cadaveric studies also support our findings. Panchbhavi et al.26 and Yongfei et al.32 found MC1–MT2 joint space widening of approximately 1.9–2 mm after ligament transection, consistent with our observed changes. Additionally, Yongfei et al.32 demonstrated that both screw and suture button fixation effectively restore pre-injury stability in cadaver models, while Chen et al.33 noted increased displacement under elastic fixation when insufficient pretension was applied—highlighting the clinical need to determine optimal intraoperative tension34,35.

Stress analysis further revealed that higher pretension levels led to increased stress concentration on the MC1, MT2, and plate interface, with von Mises stresses remaining well below the titanium yield strength (896 MPa)36,37. And the medial cuneiform exhibited higher stress than the plate itself at high pretension, potentially due to anatomical morphology dispersing loads—particularly at the distal plantar prominence.

These findings suggest that elastic fixation with moderate pretension (around 70 N) provides a favorable balance between mechanical stability and physiological function, potentially supporting early weight-bearing and improved functional recovery.

To translate the findings of this study into clinical practice, we draw on the example of the torque wrench used in fracture plate fixation. This tool ensures screws are tightened to an appropriate level without causing thread damage from excessive torque. Equipped with a preset torque limit, the wrench emits a distinct “click” once the target torque is reached, preventing overtightening. Applying this principle, a similar tensioning device could be developed for elastic fixation of Lisfranc injuries. This device would apply tension to the fixation construct until a predetermined force is achieved, then automatically stop further tensioning, thus ensuring consistent and optimal pretension intraoperatively. Future work will involve collaboration with medical device manufacturers to design and validate such a device, aiming to improve surgical precision and patient outcomes.

This study has several limitations. First, only a single foot model was used under static unipedal loading, which does not fully represent the dynamic biomechanical conditions during gait. Future studies should incorporate multiple anatomies and simulate full gait cycles to enhance generalizability. Second, bones were modeled as isotropic materials, simplifying their inherently anisotropic nature; incorporating patient-specific CT data could improve material accuracy. Third, the boundary conditions applied—specifically the complete fixation of the tibia and fibula—may over-constrain physiological motion, as highlighted by Malakoutikhah et al.37. However, given the quiet standing simulation focus on plantar load distribution, this simplification is commonly accepted in the literature and justified under static conditions where rotational degrees of freedom are minimal. We have added this rationale and the relevant citation to the discussion. Finally, our conclusions rely on computational simulations and require experimental validation. Future work should include cadaveric studies to confirm biomechanical predictions and clinical investigations using patient-specific modeling to assess applicability across diverse populations.

Conclusion

This study shows that elastic fixation can prevent abnormal movement in the Lisfranc joint and provides the optimal pretension for proper reduction. A pretension of 70 N enhances the biomechanical stability of the Lisfranc joint complex, achieving results similar to the normal model. These findings can be considered when selecting a surgical method for patients with Lisfranc injuries.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Faraco S M et al. EPIDEMIOLOGICAL STUDY ON LISFRANC INJURIES. Acta Ortopedica Brasileira. 25 (1), 44–47 (2017).

Santos-real R D L, CANILLAS, F. et al. Lisfranc joint ligament complex reconstruction: A promising solution for missed, delayed, or chronic Lisfranc injury without arthritis. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 56 (6), 1350–1356 (2017).

T P V et al. Nonoperative, open reduction and internal fixation or primary arthrodesis in the treatment of Lisfranc injuries: a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial - study protocol. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 19 (1), 301 (2018).

Dong W, Sroka O, Campbell M, et al. Recovery curves for Lisfranc ORIF using PROMIS physical function and pain interference. J. Orthop. Trauma. 38 (5), 175–181 (2024).

Qiao Y S, Li J K, Shen, H. et al. Comparison of arthrodesis and Non-fusion to treat Lisfranc injuries. Orthop. Surg. 9 (1), 62–68 (2017).

Li, B. & Zhao, W. Efficacy of open reduction and internal fixation with a miniplate and Hollow screw in the treatment of Lisfranc injury. Chin. J. Traumatol. 18 (1), 18–20 (2015).

Mohd M M F, Ajit S V & Faissal Y N. Outcome of surgically treated Lisfranc injury: a review of 34 cases. Ulusal Travma ve acil Cerrahi dergisi = turkish. J. Trauma. Emerg. Surgery: TJTES. 17 (6), 504–508 (2011).

BoffelI T J, Collier R C, Schnell, K. R. Combined medial column arthrodesis with open reduction internal fixation of central column for treatment of Lisfranc Fracture-Dislocation: A review of consecutive cases. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 57 (6), 1059–1066 (2018).

Hawkinson M P, Tennent D J, Belisle, J. et al. Outcomes of Lisfranc injuries in an active duty military population. Foot Ankle Int. 38 (10), 1115–1119 (2017).

Hoskins, M. & WISE, P. Early outcomes of Lisfranc injuries treated with arthrex internalbrace: A case series. Indian J. Orthop. 58 (3), 257–262 (2024).

Perez M T, Owen J R, Adelaar, R. S. et al. Computational analysis of Lisfranc surgical repairs. J. Orthop. Res. 40 (12), 2856–2864 (2022).

Denove N, Muriuki M G, Juntavee V,. et al. Simulated weightbearing and articular injury from transarticular screws in a ligamentous Lisfranc injury model [J]. Foot Ankle Int. 44 (10), 1044–1050 (2023).

Ahmed, S. & Bolt, B. Comparison of standard screw fixation versus suture button fixation in Lisfranc ligament injuries [J]. Foot Ankle Int. 31 (10), 892–896 (2010).

Panchbhavi V K, Vallurupalli S, Yang J, et al.Screw fixation compared with suture-button fixation of isolated Lisfranc ligament injuries [J]. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 91 (5), 1143–1148 (2009).

Zeng, G. et al. Internal Brace fixation technique for Lisfranc injury: A retrospective study [J]. Med. Sci. Monit. 30, e943537 (2024).

O’connor K P, Olfson E R, RIEHL, J. T. Flexible fixation versus open reduction internal fixation and primary arthrodesis for ligamentous Lisfranc injuries: A systematic review and meta-analysis [J]. Foot (Edinb). 61, 102145 (2024).

Ramlee M H et al. Finite element analysis of three commonly used external fixation devices for treating type III Pilon fractures [J]. Med. Eng. Phys. 36 (10), 1322–1330 (2014).

Chu, T. M., Reddy, N. P. & Padovan, J. Three-dimensional finite element stress analysis of the polypropylene, ankle-foot orthosis: static analysis. Med. Eng. Phys. 17 (5), 372–379 (1995).

Akrami, M. et al. Subject-specific finite element modelling of the human foot complex during walking: sensitivity analysis of material properties, boundary and loading conditions. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 17 (2), 559–576 (2018).

Tao, K. et al. Relative contributions of plantar fascia and ligaments on the arch static stability: a finite element study. Biomed. Tech. (Berl). 55 (5), 265–271 (2010).

Gefen A. Stress analysis of the standing foot following surgical plantar fascia release. J Biomech, 35(5): 629 – 37(2002).

Athansiou K A et al. Biomechanical topography of human articular cartilage in the first metatarsophalangeal joint. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 3(348): 269–281 (1998).

Cheung J T, ZHANG, M. et al. Three-dimensional finite element analysis of the foot during standing–a material sensitivity study. J. Biomech. 38 (5), 1045–1054 (2005).

Henning, J. A. et al. Open reduction internal fixation versus primary arthrodesis for Lisfranc injuries: a prospective randomized study. Foot Ankle Int. 30 (10), 913–922 (2009).

LY T V, COETZEE, J. C. Treatment of primarily ligamentous Lisfranc joint injuries: primary arthrodesis compared with open reduction and internal fixation. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 88(3): 514 – 20(2006).

Vallurupalli, P. A. N. C. H. B. H. A. V. I. V. K. & Yang, S. Screw fixation compared with suture-button fixation of isolated Lisfranc ligament injuries. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 91 (5), 1143–1148 (2009).

Lattermann, C. et al. Practical management of Lisfranc injuries in athletes. Clin. J. Sport Med. 17 (4), 311–315 (2007).

Er, M. S. & Verim, O. Biomechanical evaluation of syndesmotic screw design via finite element analysis and taguchi’s method. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 105 (1), 14–21 (2015).

Westermann R W, Rungprai, C. et al. The effect of suture-button fixation on simulated syndesmotic malreduction: a cadaveric study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 96 (20), 1732–1738 (2014).

Charlton, T. & Boe, C. Suture button fixation treatment of chronic Lisfranc injury in professional dancers and High-Level athletes. J. Dance Med. Sci. 19 (4), 135–139 (2015).

CHUN D I, KIM, J. et al. Fixation of isolated Lisfranc ligament injury with the TightRope™: A technical report. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res, 107(6): 102940 (2021).

Yongfei, F. et al. Clinical outcomes of tightrope system in the treatment of purely ligamentous Lisfranc injuries. BMC Surg. 21 (1), 395 (2021).

Chen, J. & Sagoo, N. The Lisfranc injury: A literature review of anatomy, etiology, evaluation, and management. Foot Ankle Spec. 14 (5), 458–467 (2021).

Urdahl T H, Dock C C, Stone Mcgaver, R. et al. Outcomes of surgically treated purely ligamentous stage II Lisfranc injuries. Foot Ankle Int. 44 (11), 1120–1127 (2023).

Güvercin, Y. et al. Suture button fixation method used in the treatment of syndesmosis injury: A Biomechanical analysis of the effect of the placement of the button on the distal tibiofibular joint in the mid-stance phase with finite elements method. Injury 53 (7), 2437–2445 (2022).

Pelt C E, Bachus K N, Vance R E, et al. A Biomechanical analysis of a tensioned suture device in the fixation of the ligamentous Lisfranc injury. Foot Ankle Int. 32 (4), 422–431 (2011).

Malakoutikhah, H. et al. Evaluation of assumptions in foot and ankle Biomechanical models[J]. Clin. Biomech. Elsevier Ltd. 100, 105807 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Prof. Cheng-wei Wang for his guidance and input during the project.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (project number: 2024D01D27).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LY completed the finite element modeling, data analysis, processing,wrote the main manuscript text and LW and LW completed data collection.The contributions of the three individuals are the same. WSW completed visualization.WCW completed the design of the experiment, supervised and guided its smooth progress.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

URL link

Mimics21.0: https://www.materialise.com/.

Geomagic Wrap: https://oqton.com/geomagic-wrap/.

HyperMesh: https://altair.com/hypermesh.

ANSYS: https://www.ansys.com/.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Lu, W., Liu, W. et al. Biomechanical analysis of elastic fixation for lisfranc injuries with finite elements method. Sci Rep 15, 26540 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11611-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11611-9