Abstract

The emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) Pseudomonas aeruginosa represents a significant challenge in managing nosocomial infections, particularly in vulnerable populations such as burn patients. This study provides genomic and molecular characterization of MDR and XDR P. aeruginosa strains isolated from burn patients at Sheikh Hasina National Institute of Burn and Plastic Surgery (SHNIBPS) in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Over an 8-month period, 110 wound swabs were collected, with 91 isolates identified as P. aeruginosa. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing demonstrated a multidrug-resistant pattern in 30 isolates and an extensive drug-resistant pattern in the remaining 61 isolates analyzed in this study. PCR assays detected beta-lactamase genes from all four Ambler classes, revealing a notable prevalence of blaNDM-1 (16.48%) and blaVIM-2 (31.87%), with both genes co-occurring in 3.30% of the isolates. Additionally, blaPER-1 (15.38%), blaCTX-M (4.40%), blaOXA-1 (84.62%), and blaOXA-48 (51.65%) genes were detected. Class I integrons were detected in 84 isolates. A total of 21% of the isolates exhibited strong biofilm-forming capabilities. Key biofilm-associated genes (pelB, pilT, rhlB) were detected in most of the isolates. Whole genome sequence analysis of two selected XDR isolates identified different beta-lactamase genes such as blaPDC-98, blaPDC-374, blaOXA-50, blaOXA-677 and blaOXA-847. Virulence factor genes, metal resistance genes, and prophage sequences were also identified in the analysis. The genomic epidemiology analysis of 9,055 P. aeruginosa strains, based on MLST data, revealed the dominance of ST235. The blaPDC and blaOXA genes were found to be notably prominent worldwide. The comparative genomic analysis of P. aeruginosa strains from Bangladesh demonstrated an expanding pangenome as well as high degree of genetic variability. The study emphasized the dynamic nature of the P. aeruginosa pangenome and underscored the necessity for stringent infection control measures in burn units to manage and mitigate the spread of these highly resistant strains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In healthcare, managing burn wound infections is a considerable challenge, as they significantly raise patient morbidity and mortality1. Among the numerous pathogens responsible for these infections, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) stands out as a particularly problematic agent, known for causing severe complications and delaying the healing process2,3. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a Gram-negative, opportunistic pathogen that is commonly associated with hospital-acquired infections4. Its ability to thrive in diverse environments, including water, soil, and clinical settings, makes it a formidable pathogen in healthcare facilities. The emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR), extensively drug-resistant (XDR) and pandrug resistant (PDR) strains of P. aeruginosa has been reported worldwide, exacerbating the challenges in clinical management5,6. These resistant strains are often linked to prolonged hospital stays, increased healthcare costs, and higher mortality rates. The spread of these strains is facilitated by their ability to form biofilms on medical devices, such as catheters and ventilators, which protect them from both the host immune system and antibiotic treatment5,7,8.

The rise of XDR P. aeruginosa represents a significant challenge in the management of nosocomial infections, particularly in vulnerable populations such as burn patients9,10. In burn units, where patients are highly susceptible to infections due to compromised skin integrity and immune function, outbreaks of XDR P. aeruginosa can lead to severe complications, prolonged hospital stays, and increased mortality rates. Infections caused by P. aeruginosa in burn wounds have been linked to prolonged hospital stays, increased healthcare costs, and, in severe cases, can lead to septicemia and death11. Over the past few decades, the extensive use and misuse of antibiotics have led to the development and spread of MDR strains of P. aeruginosa. Recently, the emergence of XDR strains has raised significant concerns among healthcare professionals due to their limited treatment options and potentially severe outcomes12.

Beta-lactam antibiotics, encompassing penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, and monobactams, have played a crucial role in treating bacterial infections since their discovery13. However, the increasing prevalence of beta-lactam antibiotic resistance has significantly compromised the effectiveness of these drugs, primarily due to bacterial production of beta-lactamase enzymes14. Besides, biofilm formation significantly enhances antimicrobial resistance in P. aeruginosa by providing a protective environment for bacterial cells15. The extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix acts as a physical barrier, limiting antibiotic penetration. Within the biofilm, bacteria exist in various metabolic states, including dormant cells less susceptible to antibiotics targeting active growth15,16. Biofilms also facilitate horizontal gene transfer, spreading antibiotic resistance genes, and harbor persister cells that can survive antibiotic treatment and repopulate the biofilm. Additionally, quorum sensing regulates biofilm development and antibiotic resistance17. Efflux pumps play a crucial role in antimicrobial resistance in P. aeruginosa by actively expelling a wide range of antibiotics from the bacterial cell, thereby reducing their intracellular concentrations and effectiveness18. These pumps, such as MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, MexEF-OprN, and MexXY, span the bacterial cell membrane and outer membrane, creating a direct route for antibiotic expulsion. Integrons are primarily recognized as the genetic entities accountable for acquiring and disseminating antibiotic resistance traits across a wide range of Gram-negative clinical isolates19. Among the main three classes of integrons, class I type integron is more significant and widespread in P. aeruginosa20. Microbial entities can rapidly acquire genes from various organisms, which may increase their virulence or promote antimicrobial resistance21. Recent epidemiological studies have revealed a rising trend in antimicrobial resistance, with a notable increase in multi-drug resistant P. aeruginosa isolates in recent years22,23.

Whole genome and metagenome sequencing have become pivotal in tackling the critical challenges posed by MDR, XDR, and PDR bacteria within the healthcare sector24,25,26,27. These sequencing technologies enable researchers to uncover extensive information, including antimicrobial resistance genes, phenotypes, virulence factors, and metabolic pathways3,28,29. Beyond these applications, sequencing also plays a vital role in epidemiological analysis by allowing high-resolution tracking of bacterial transmission pathways, identifying outbreak sources, and monitoring the emergence and spread of resistance traits across populations30,31. This comprehensive understanding is essential for developing effective strategies to combat the severe impact of these resistant organisms. In the current study, WGS approach is applied to investigate the genetic landscape of two XDR P. aeruginosa strain, with a specific focus on its AMR gene repertoire, mobile genetic elements, and virulence factors. Additionally, advanced applications such as phylogenomic, pangenome analysis and comparative genomics are leveraged to explore the genomic dynamics of these strain, shedding light on its relationship to other clinically significant P. aeruginosa isolates from Bangladesh.

In Bangladesh, the situation is particularly alarming due to the high prevalence of P. aeruginosa in burn units, coupled with limited resources for effective infection control and antimicrobial stewardship3,32,33. This study offers detailed genomic and molecular insights into MDR and XDR P. aeruginosa strains isolated from burn patients in a major burn unit hospital in Bangladesh, with a specific focus on XDR strains. By analyzing the resistance patterns, virulence factors, and genetic diversity of these isolates, we aim to understand the burden of drug resistance and pathogenicity in this critical clinical setting. The study emphasized the dynamic nature of the P. aeruginosa pangenome and underscored the importance of stringent infection control measures in burn units to manage and mitigate the spread of these highly resistant strains.

Results

Sample collection and isolate identification

Out of the initial 110 samples, 91 were selected for detailed analysis following preliminary assessment. From these 91 samples, 91 bacterial strains (n = 91) were successfully isolated which were responsible for causing infection in the burn wounds of the injured patients. The cohort of patients (n = 91) from whom these samples were obtained included 62 males and 29 females, representing various age groups (Supplementary Fig. 2). Through biochemical and cultural identification, the 91 isolates were presumptively identified as P. aeruginosa. After that, molecular identification through marker gene specific PCR confirmed and validated the isolates to be P. aeruginosa (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Extensive drug resistance pattern of P. aeruginosa in burn wound infection

The antimicrobial resistance pattern of 91 isolates of P. aeruginosa in 15 antibiotics of 8 categories were determined. More than 80% of the isolates showed resistance to aminoglycosides and 69 isolates showed resistance in all three of the aminoglycosides tested such as amikacin, tobramycin and gentamicin. Besides, > 80% of the isolates showed resistance to fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin (Fig. 1a). Out of the 91 isolates examined in this study, 76 demonstrated resistance to meropenem, while 42 exhibited resistance to imipenem. On the other hand, all of the isolates showed sensitivity to polymyxin B and colistin. Thirty isolates demonstrated resistance to at least one agent within a minimum of three antimicrobial groups, indicating multidrug-resistance pattern. All the isolates were categorized as MDR. Notably, 61 out of the 91 isolates were categorized as XDR, highlighting their heightened resistance to a broad spectrum of drugs.

Comprehensive analysis of antimicrobial resistance and genetic determinants in drug-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates. (a) Antibiotic susceptibility profile of the isolates against 14 antibiotics. (b) Prevalence and distribution of beta-lactamase genes harbored by the isolates. (c) Prevalence and distribution of efflux.

Antibiotic resistance genes investigation

Antibiotic resistance genes investigation revealed the abundance of beta lactamase producing genes. Fifteen (16.48%) isolates among the total 91 isolates of P. aeruginosa were detected to harboring blaNDM-1 type genes (Fig. 1b). On the other hand, blavim-2 type genes were found in 29 isolates. The co-existence of blaNDM-1 and blaVIM-2 type genes was detected in three isolates. Besides, blaPER-1 and blaCTX-M type genes, which are class A beta lactamase gene, was found in 14 and 4 isolates respectively. However, class D beta lactamase blaOXA-1 like genes were detected in 77 isolates and 47 isolates carried blaOXA-48 type genes. Class I Integron was detected in 84 isolates among all 91 drug resistant isolates. Efflux pump gene investigation revealed that mexA, mexC and mexE genes were carried by most of the test isolates (Fig. 1c). Interestingly, only one isolate was found where no mexA, mexC or mexE genes were detected.

Strong biofilm formation and abundance of associated genes

After completion of the biofilm formation assay, it was found that all the isolates were biofilm former. Among them, 19 (21%) isolates were detected as SBF and 45 isolates (49%) were found to be MBF (Fig. 2a). On the other hand, 27 isolates (30%) were found to be weak biofilm former. Biofilm formation and virulence associated genes investigation revealed the presence of pelB gene in 90 isolates among the 91 test isolates (Fig. 2b). Besides, pilT and rhlB genes were detected in 88 and 63 isolates respectively.

Whole genome sequence analysis revealed MLST, serogroup and diverse genomic features

The WGS-based identification confirmed the two selected isolates to be two different strains of P. aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS64 and P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS243). The multi locus sequence typing (MLST) and serotyping indicated toward two different sequence types and serotypes of the two isolates respectively. P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS64 was predicted to be of multi locus sequence type 664 (MLST 664) and serotype O7. Conversely, accurate detection of the MLST for P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS243 was hindered due to insufficient sequence coverage, particularly in the guaA and mutL loci. But, the closest sequence type determined for the isolate was ST 3934. However, serotype determination revealed that P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS243 was of serotype O12. After annotation and mapping, genomes of the two isolates showed different features (Table 1 and Fig. 3).

Antimicrobial resistance genes investigation revealed co-existence of different types of beta lactamase and efflux pump genes

Investigation of antimicrobial resistance genes from whole genome sequences of the two isolates revealed a numerous number and types of antimicrobial resistance genes. These genes and gene products are responsible for conferring resistance to different antibiotics. Pseudomonas aeruginosa SHNIBPS64 and P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS243 harbored around 50 and 28 antimicrobial resistance genes respectively. The co-existence of blaPDC-98 (Class C) and blaOXA-50 (Class D) beta lactamase producing genes were found in P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS64 (Fig. 4a). Along with that, two mutations (S209R, G71E) were observed in nalC gene (Supplementary Table 3). On the other hand, in case of P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS243, co-existence of class C (blaPDC-374) and class D (blaOXA-677 and blaOXA-847) beta lactamase genes were observed (Fig. 5a). No mutations in nalC gene was observed in this isolate (Supplementary Table 4). T83I mutation in gyrA gene was detected in both P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS64 and P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS243. Besides, both isolates harbored sul1 gene which is responsible for conferring resistance to sulfonamide antibiotics. Along with that, qacL and qacDelta1 genes were present in the isolates which confer resistance to disinfecting agents and antiseptics. Analysis of genes associated with efflux pumps identified various genes, including mexA, mexB, mexC, mexE etc., participating in the development of diverse efflux pumps that are recognized for their role in bestowing resistance to multiple antibiotics (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). The efflux pump-related proteins accountable for the creation of distinct efflux pump operons are provided in the Table 2.

Mobile genetic elements investigation

Analysis revealed around 40 mobile genetic elements in case of both P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS64 and P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS243. Major MGEs found in P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS64 were ISPa100, ISPa32, ISPa1, IS6100, ISPsp1, cn_5674_ISPsp1. On the other hand, in case of P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS243, the major MGEs detected were ISPa37, ISPa32, ISPa6, IS6100, ISPa1, ISPa22, ISPa100, IS26, ISAs31, cn_2637_ISAs31. In depth investigation around the antimicrobial resistance genes revealed the presence of several mobile genetic elements and genes responsible for integration, excision and transfer of genetic materials (Figs. 4b and 5b). The informative genome mapping revealed that within P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS243, numerous antimicrobial resistance genes, including blaOXA-677, ant(3″)-lla, sul1, and qacE, were flanked by mobile genetic elements such as tniB, tnpA, tnpM, tnpR, intS, and others which play crucial role in integration, excision and transfer of genes (Fig. 5c). Additionally, several genes and mobile genetic elements were identified near blaOXA-847 and blaPDC-374 (Fig. 5d,e). In the case of P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS64, numerous genes and elements potentially involved in the integration, excision, and transfer of genetic materials were found surrounding antimicrobial resistance genes, specifically blaPDC-98, blaOXA-50, ant(4′)-llb, sul1, and aph(3′)-llb (Fig. 4c,d). For both isolates, it is evident that numerous antimicrobial resistance genes are encircled by mobile genetic elements accountable for the excision, integration, and transfer of genes (Figs. 4 and 5).

Detection of prophage in the genome sequences

Prophage investigation in the two test isolates revealed numbers of phage sequences and associated genes integrated into the bacterial genomes (Supplementary Fig. 5). Further in-depth investigation revealed several active phage sequences integrated into the genomes of the two bacterial isolates (Table 3). Most of the prophage sequences identified were of different Pseudomonas phages. Notably, the phage integration analysis uncovered the integration of a Marinobacter phage sequence in the genome of P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS243. This phage, belonging to the Podoviridae family, was not found in its entirety; however, a significant portion comprising 23 genes was integrated into the bacterial genome. Additionally, P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS64 exhibited integration of Erythrobacter phage sequences. An intriguing aspect of this analysis was the detection of genes associated with antimicrobial resistance within the prophage regions integrated into the bacterial genomes. Specifically, in P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS243, the msrE gene was identified within the prophage sequence region (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Similarly, in P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS64, the parR and parS genes were found to be integrated within the prophage sequences as detected by the VirSorter tool (Supplementary Fig. 6a).

Virulence factor and metal resistance genes investigation

The virulence factor genes identified in the P. aeruginosa isolates SHNIBPS64 and SHNIBPS243 were categorized into several key functional groups (Supplementary Tables 5, 6 and Supplementary Fig. 3). Both isolates contained genes related to adherence, with SHNIBPS64 having 42 flagella-related genes (e.g., flaG, fleN, fliC) and 23 type IV pili genes (e.g., fimT, pilA, pilQ), while SHNIBPS243 had 32 flagella-related genes (e.g., flaG, fleN, fliC) and 21 type IV pili genes (e.g., fimT, pilA, pilQ). Antimicrobial activity genes included phenazine biosynthesis genes in both isolates, with SHNIBPS64 having nine (e.g., phzA1, phzS) and SHNIBPS243 having seven (e.g., phzA1, phzS). Antiphagocytosis-related genes were found in both isolates, with SHNIBPS64 containing 12 alginate biosynthesis genes (e.g., algD, algG) and SHNIBPS243 containing 10 (e.g., algD, algG). Both isolates had genes for rhamnolipid biosynthesis (e.g., rhlA, rhlC in SHNIBPS64; rhlA, rhlB in SHNIBPS243). Enzymatic activity genes were noted in both isolates, with hemolytic phospholipase C (plcH), non-hemolytic phospholipase C (plcN), and phospholipase C (plcB) present in SHNIBPS64, and additionally phospholipase D (pldA) in SHNIBPS243. Iron uptake mechanisms included genes related to pyoverdine biosynthesis (e.g., pvdA, pvdQ in SHNIBPS64; pvdE, pvdN in SHNIBPS243), one pyoverdine receptor gene (fpvA) in both isolates, and pyochelin biosynthesis genes (e.g., pchA, pchR in SHNIBPS64; pchA, pchE in SHNIBPS243). Protease-related virulence factors were represented by alkaline protease (aprA), elastase (lasA, lasB in SHNIBPS64), and protease IV (prpL) in both isolates. Quorum sensing included genes for acylhomoserine lactone synthase (hdtS) and both lasI/lasR and rhlI/rhlR systems in SHNIBPS64, and hdtS and rhlI/rhlR system in SHNIBPS243. The secretion system category featured genes for Pseudomonas syringae TTSS effectors, Hcp secretion island-1 type VI secretion system, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa TTSS translocated effectors in SHNIBPS64, and the Hcp secretion island-1 type VI secretion system and Pseudomonas aeruginosa TTSS translocated effectors (e.g., exoS, exoT, exoY) in SHNIBPS243. Toxin production was indicated by exotoxin A (toxA) and hydrogen cyanide production genes (hcnA, hcnB, hcnC) only in SHNIBPS64. Immune evasion included genes related to capsule formation present only in SHNIBPS64. Comparative analysis showed that both isolates had 185 virulence factor genes in common. The findings highlighted the extensive virulence potential of both isolates, with SHNIBPS64 exhibiting a broader spectrum of virulence factors, including additional toxin production and immune evasion genes. Metal resistance genes investigation also revealed several genes responsible for conferring resistance against different metals (Supplementary Table 7).

Subsystems and metabolic pathways investigation

The comparative subsystem category distribution analysis between P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS64, P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS243 and P. aeruginosa PAO1 (Reference Strain) revealed differences across various metabolic and functional categories (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 8). Carbohydrate metabolism is markedly more prevalent in SHNIBPS64, displaying 304 features, whereas SHNIBPS243 has 229 features. In terms of protein metabolism and cofactor synthesis, both isolates showed relatively similar counts, with SHNIBPS64 having 215 and 189 features, respectively, compared to 203 and 185 in SHNIBPS243. Membrane transport features were higher in SHNIBPS64, with 184 features, while SHNIBPS243 has 152 features. Fatty acids, lipids, and isoprenoids metabolism exhibited a slight increase in SHNIBPS243, showing 142 features compared to 131 in SHNIBPS64. Additionally, respiration-related features were higher in SHNIBPS64 (126 features) compared to SHNIBPS243 (109 features). Significant disparities were observed in categories such as iron acquisition and metabolism, with SHNIBPS64 showing 108 features versus 51 in SHNIBPS243 and PAO1. Notably, virulence, disease, and defense mechanisms are more prevalent in SHNIBPS64, with 85 features compared to 67 in SHNIBPS243. On the other hand. The reference strain P. aeruginosa PAO1 contained only 62 features in the virulence, disease, and defense mechanisms category. Further, the distribution of features in other metabolic processes, such as the metabolism of aromatic compounds, nucleosides and nucleotides, and RNA metabolism, was slightly higher in SHNIBPS64 compared to SHNIBPS243. Categories such as sulfur metabolism, potassium metabolism, motility, and chemotaxis also show higher counts in SHNIBPS64.

The metabolic pathways of P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS64 and P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS243 were compared to elucidate their distinct metabolic capabilities (Supplementary Table 9). The primary metabolic pathways identified in both strains include the citrate cycle (TCA cycle), glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and the pentose phosphate pathway. These strains also engage in various amino acid metabolism processes, such as those involving alanine, aspartate, and glutamate. Additionally, they share pathways for the metabolism of fatty acids, pyruvate, and butanoate. Notable secondary metabolite pathways include isoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis and novobiocin biosynthesis, shared by both strains. However, P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS243 exhibits additional secondary metabolite pathways, such as tropane, piperidine, and pyridine alkaloid biosynthesis, indicating a broader metabolic versatility. The xenobiotics biodegradation pathways further highlight the differences between the strains. Both SHNIBPS64 and SHNIBPS243 possess pathways for the degradation of caprolactam, gamma-hexachlorocyclohexane, 2,4-dichlorobenzoate, benzoate via hydroxylation, fluorobenzoate, toluene and xylene, atrazine, bisphenol A, and ethylbenzene. Unique to SHNIBPS243 are pathways for the degradation of styrene, naphthalene and anthracene, tetrachloroethene, and DDT, alongside drug metabolism pathways involving cytochrome P450 and other enzymes and geraniol degradation.

Genome-wide beta-lactam resistance gene pool investigation

The investigation into the genome-wide beta-lactam resistance gene pool in P. aeruginosa isolated from both human and non-human sources reveals significant differences in the abundance and diversity of resistance genes (Fig. 6a,b). The analysis included 6574 (n = 6574) P. aeruginosa whole genomes, encompassing the two isolates from this study. Among these, 6408 (n = 6408) genomes were from human sources, and 166 genomes (n = 166) were from non-human sources. P. aeruginosa isolates from human sources, indicated a diverse array of beta-lactam resistance genes. Overall, the blaPDC and blaOXA genes are notably prominent in both human and non-human isolates, with the highest abundance observed in human isolates. In non-human isolates, these genes also exhibit significant abundance. Other resistance genes such as blaVIM, blaNDM, blaSIM, blaIMP, blaGES, blaKPC, blaSPM, blaADC, blaCMY, and blaDHA are present in human isolates but at much lower abundances. These genes are minimally represented or nearly absent in non-human isolates. Additionally, genes like blaPER, blaTEM, blaCTX-M, blaSHV, blaVEB, blaCARB, and blaAMPc appear in human isolates with minimal representation, while in non-human isolates, blaACT, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaCTX-M, blaTEM, and blaGES are present but with very low counts. The comparative analysis suggests that P. aeruginosa from human sources harbors a more extensive and abundant repertoire of beta-lactam resistance genes compared to those from non-human sources.

Genome wide beta lactam resistance genes analysis of 6,574 publicly available P. aeruginosa genome worldwide. (a) Distribution of beta lactam resistance genes of P. aeruginosa isolated from human sources. (b) Distribution of beta lactam resistance genes of P. aeruginosa isolated from non-human sources.

Pangenome analysis, epidemiological pattern and pathogenicity profiling

The pangenome analysis of P. aeruginosa strains with all the 12 genomes available from Bangladesh revealed significant genetic diversity, characterized by a relatively small core genome comprising 3,670 genes (27%) and a substantial proportion of accessory genes (soft core, shell, and cloud genes collectively making up 72.9%) (Fig. 7a–c). The phylogenetic tree and heatmap highlight the varied evolutionary relationships and gene distributions across the strains (Fig. 7a). The pie chart and gene count summary further emphasize the predominance of accessory genes, with 4991 soft core genes (37%) and 4900 shell genes (36%), underscoring the open nature of the pangenome. This extensive accessory gene pool indicates ongoing gene acquisition, contributing to the species’ adaptability and genetic plasticity. The gene alignment plot corroborates these findings by showing significant homologous regions and structural variations among the strains (Fig. 7d). Collectively, these results suggest that P. aeruginosa maintains a highly dynamic and open pangenome, which likely enhances its environmental resilience and pathogenic potential.

Pangenome and Comparative genomic analysis of all the publicly available P. aeruginosa genomes from Bangladesh. (a) Pangenome and phylogenomic analysis based on core genome alignment, illustrating the genetic relationships among the isolates. (b,c) Pangenome composition highlighting the distribution of core, soft core, shell, and cloud genes across the isolates. (d) Genome alignment using Mauve depicting the extensive genomic rearrangements and variability in the genomes.

The prediction of the global distribution of P. aeruginosa strains based on the publicly available MLST data revealed highest concentration in regions such as North America, Europe, China, Brazil, and Australia (Fig. 8a). The genomic epidemiology analysis of 9,055 P. aeruginosa strains, based on MLST data, reveals a complex population structure with notable prevalence of specific sequence types (STs) (Fig. 8b). The analysis identifies ST 235, ST 253, ST 111, ST 395, ST 308, ST 244, ST 175 and ST 274 as the most prevalent, indicating their widespread dissemination and clonal expansion across various regions. ST 235, ST 253 and ST 111 are particularly dominant, suggesting a significant role in the global epidemiology of P. aeruginosa.

Global distribution and MLST based epidemiological analysis of P. aeruginosa strains. (a) Geographic distribution of P. aeruginosa strains across the world, with countries shaded according to the number of strains sampled. (b) Global epidemiological analysis based on MLST of P. aeruginosa strains worldwide.

The pathogenicity analysis of various P. aeruginosa strains isolated in Bangladesh highlighted significant differences in their pathogenic profiles (Fig. 9a). Notably, P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS64, P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS243, P. aeruginosa SRS1 and P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS206 exhibited the relatively higher pathogenicity. In contrast, strains like P. aeruginosa TG523, P. aeruginosa DMC-20C, P. aeruginosa DMC-30b and P. aeruginosa MZA4A showed moderate pathogenicity prediction, whereas P. aeruginosa DMC-27b had a lower pathogenicity. In terms of matched pathogenic families, P. aeruginosa DMC-30b and P. aeruginosa TG523 showed the highest number of pathogenic families, indicating a broad range of pathogenic mechanisms (Fig. 9b). Conversely, despite their high pathogenicity scores, P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS64 and P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS243 matched fewer experimental pathogenic families.

Comparative analysis of pathogenicity and matched pathogenic families among different Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated in Bangladesh. (a) Pathogenicity scores of the strains, with a color gradient indicating the level of pathogenicity (blue to red, from lower to higher pathogenicity). The strains are listed along the y-axis, with their corresponding pathogenicity scores on the x-axis. (b) Number of matched pathogenic families for each strain, represented as horizontal bars. Strains are listed along the y-axis, and the number of matched pathogenic families is shown on the x-axis.

Discussion

The analysis of 91 P. aeruginosa strains isolated from burn wound infections provided important insights into its prevalence in clinical settings. The successful isolation of these strains underscored the significant burden of P. aeruginosa in burn wound infections, highlighting its role as a major causative agent. The consistently high isolation rate observed highlighted the critical role of P. aeruginosa as a dominant etiological agent in burn wound infections and underscored the importance of robust infection control practices. There are several reports of the high prevalence of P. aeruginosa in clinical settings34,35,36,37. This alarming high prevalence also emphasizes the need for ongoing surveillance and effective antimicrobial stewardship to mitigate the risk of outbreaks and manage antibiotic resistance associated with this opportunistic pathogen.

The extensive drug resistance observed in P. aeruginosa isolates from burn wound infections highlighted a critical public health challenge. The high resistance rates to aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones, as well as the significant resistance to carbapenems, reflect the adaptability and resilience of P. aeruginosa in clinical settings, particularly in burn units where patients are highly susceptible to severe infections. Interestingly, the isolates demonstrated higher resistance to meropenem compared to imipenem. This finding contrasts with several previous studies in which Gram-negative bacilli exhibited greater susceptibility to meropenem than to imipenem38,39. The universal sensitivity to polymyxin B and colistin provides a potential treatment pathway, although their use must be carefully managed due to toxicity concerns. The detection of various beta-lactamase genes, such as blaNDM-1, blaVIM-2, blaPER-1, blaCTX-M, blaOXA-1, and blaOXA-48, highlighted the complexity of resistance mechanisms in these isolates. This diversity of resistance genes reflects the genetic adaptability of the isolates and their ability to counteract a broad range of beta-lactam antibiotics40,41. The co-existence of multiple beta-lactamase genes in some strains suggests a heightened capacity for resistance, making infections harder to treat. Class I integrons play a significant role in the dissemination of resistance genes, highlighting the dynamic nature of genetic exchange in P. aeruginosa. The widespread presence and overexpression of efflux pump genes, including mexA, mexC, and mexE, significantly contributes to the multidrug resistance phenotype by actively expelling a broad range of antibiotics from bacterial cells42. These efflux pumps reduce the intracellular concentration of antimicrobial agents, thereby diminishing their efficacy This mechanism, combined with other resistance determinants, complicates therapeutic interventions.

The strong biofilm formation observed in the P. aeruginosa isolates from burn wound infections presents a significant challenge for treatment and patient outcomes. The investigation into biofilm-associated genes revealed a high prevalence of pelB, pilT, and rhlB genes among the isolates. The pelB gene, detected in 90 of the 91 isolates, plays a crucial role in the production of the polysaccharide matrix that constitutes the biofilm, enhancing structural integrity and protection. The presence of pilT and rhlB genes highlighted their role in biofilm formation and its regulation. These genes contribute to key processes such as surface attachment and biofilm maintenance, which are critical for bacterial survival and persistence. PilT is involved in type IV pilus-mediated motility, which is essential for initial surface attachment and biofilm development43, while rhlB is part of the rhamnolipid biosynthesis pathway, contributing to biofilm maturation and maintenance44. In the context of burn wound infections, the strong biofilm-forming capacity of P. aeruginosa exacerbates the clinical management of these infections. Biofilms serve as reservoirs for bacterial cells, protecting them from antibiotic penetration and immune clearance45. This makes eradication difficult, often leading to recurrent infections and increased morbidity. The correlation between biofilm formation and the presence of specific virulence genes suggests that these isolates are well-equipped to establish and maintain chronic infections in burn wounds.

Whole genome sequencing of two XDR P. aeruginosa isolates (P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS64 and P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS243) isolated from burn wound infections in this study revealed their detailed genomic characteristics. The identification of two different sequence types and serotypes underscored the variability within P. aeruginosa populations in clinical settings. This diversity is crucial in understanding the adaptability and pathogenic potential of these strains. The presence of multiple beta-lactamase genes and efflux pump genes in both isolates aligns with existing literature on the mechanisms P. aeruginosa employs to evade antibiotic treatment42,46,47. The co-existence of class C and class D beta-lactamases, as well as mutations in resistance-associated genes such as nalC and gyrA, contributes to a robust defense against a wide range of antibiotics48,49,50. These genetic arsenals may complicate treatment regimens, particularly in burn patients who are already vulnerable to severe infections. The detection of sul1, qacL, and qacDelta1 genes, conferring resistance to sulfonamides and disinfectants, further illustrates the resilience of these strains in hospital environments where such agents are frequently used. This resilience can lead to persistent infections and outbreaks, making infection control measures more challenging. Efflux pump genes, including mexA, mexB, mexC, and mexE, are well-documented contributors to multidrug resistance in P. aeruginosa42,51. Their presence in these isolates highlights the importance of efflux mechanisms in the survival and proliferation of this pathogen in hostile environments, such as burn wounds treated with multiple antibiotics.

The integration of active phage sequences into the genomes of P. aeruginosa strains SHNIBPS64 and SHNIBPS243 provides significant insights into the genomic plasticity and potential adaptive advantages conferred by prophages. The presence of Pseudomonas, Marinobacter, and Erythrobacter phages underscores the role of horizontal gene transfer in enhancing bacterial fitness. Notably, the Marinobacter phage integration in SHNIBPS243, with a significant portion of 23 genes, and the Erythrobacter phage sequences in SHNIBPS64 highlight cross-genus phage integration. A critical finding is the detection of antimicrobial resistance genes within these prophage regions. The msrE gene in SHNIBPS243 and the parR and parS genes in SHNIBPS64 suggest that phage integration can disseminate resistance traits, enhancing bacterial survival under antibiotic pressure. This phage-mediated transfer of resistance genes underscores the role of prophages in the evolution of antibiotic resistance. These insights emphasize the need to consider phage dynamics in developing therapeutic strategies against P. aeruginosa. Targeting phage-bacterium interactions and the mobilization of resistance genes via prophages could be pivotal in mitigating antimicrobial resistance and managing infections caused by these resilient pathogens.

The subsystem feature distribution underscores the metabolic and functional versatility of P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS64 compared to P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS243, particularly in areas related to metabolism, iron acquisition, virulence, and stress responses, which could have significant implications for their adaptability and pathogenicity. The diverse metabolic capabilities are essential for the bacteria’s energy production, biosynthesis, and overall survival in nutrient-limited environments like burn wounds. The analysis of xenobiotics biodegradation pathways highlights the ability of both strains to degrade a wide range of environmental pollutants and toxic compounds. The capability to metabolize diverse xenobiotics suggests that these isolates can survive in environments with high levels of chemical contaminants, including those found in hospital settings. The presence of pathways for drug metabolism and other enzymes, alongside unique pathways for the degradation of complex xenobiotics indicates their potential to resist multiple antimicrobial agents. This metabolic flexibility and the ability to detoxify harmful compounds may contribute to their persistence and the difficulty in eradicating from hospital environments. The high counts of iron acquisition and virulence features suggest that these strains are well-equipped to acquire essential metals and deploy effective pathogenic strategies, which are critical for their growth and infection in iron-limited host environments. The enhanced virulence mechanisms further highlighted their potential to effectively colonize and persist in burn wound sites, evading host immune defenses.

The open pangenome of P. aeruginosa strains from Bangladesh, as evidenced by the large number of accessory genes, implied continuous horizontal gene transfer events and genomic rearrangements. This characteristic is particularly concerning from a clinical perspective, as it may facilitate the emergence of new virulent strains with enhanced resistance to antibiotics and other therapeutic interventions52. The observed genetic diversity also reflected the pathogen’s ability to occupy different ecological niches, thereby increasing its survival and propagation potential. The phylogenetic tree and gene distribution heatmap underscored the evolutionary relationships and gene content variability among the strains, suggesting that even within a localized region, P. aeruginosa exhibits considerable genetic heterogeneity. This diversity could be a response to selective pressures in the environment, including exposure to different antimicrobial agents and competition with other microbial species. Overall, the findings underscore the importance of monitoring the genetic evolution of P. aeruginosa. Understanding the dynamics of its pangenome can provide crucial insights into its pathogenic mechanisms and inform the development of more effective treatment strategies and public health interventions. The open nature of its pangenome highlights the need for continuous surveillance and research to mitigate the risks associated with this adaptable and potentially hazardous pathogen.

The comparative analysis of pathogenicity among various P. aeruginosa strains isolated from Bangladesh revealed significant heterogeneity in their virulence profiles, with implications for clinical management and therapeutic interventions. The high pathogenicity scores observed in P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS64 and P. aeruginosa SHNIBPS243 suggested these strains possess potent virulence factors capable of causing severe infections. Interestingly, despite their high pathogenicity, these strains exhibited a lower number of matched pathogenic families. This discrepancy between high pathogenicity scores and a lower number of matched pathogenic families suggest that these strains possess highly potent pathogenic mechanisms that may not be reflected solely by the number of matched pathogenic families. These strains may rely on a few highly effective pathogenic mechanisms rather than a broad array of virulence factors. The results also suggest that these isolates may possess numerous proteins associated with unknown or uncharacterized pathogenic families that are not included in the current database. This presents a significant opportunity for further research to identify and characterize these proteins, which could enhance our understanding of the mechanisms and dynamics of their pathogenicity, particularly in causing wound infections and various hospital-acquired infections. Furthermore, such research could open new aspects for identifying therapeutic targets and developing novel treatments to combat these highly pathogenic organisms.

There is an urgent need to implement robust infection control strategies, ensure continuous surveillance, and accelerate the development of novel antibiotics or alternative therapeutic approaches. Understanding the mechanisms underlying resistance and targeting specific pathways, such as beta-lactamase activity and efflux pumps, could enhance the effectiveness of existing treatments. Moreover, the high prevalence of resistance genes calls for ongoing research into innovative strategies to combat these highly adaptable and pathogenic organisms, ensuring better outcomes for patients with burn wound infections.

Conclusion

This study provides molecular characterization of MDR and XDR P. aeruginosa strains isolated from burn patients in Bangladesh. Additionally, it offers a comprehensive genomic analysis of two representative XDR strains, leveraging whole-genome sequencing to elucidate their genetic features and resistance mechanisms. The identification of high prevalence of beta-lactamase genes, efflux pump genes, biofilm associated genes, class I integron highlighted the formidable nature of these pathogens as well as underscored the multifaceted mechanisms driving antimicrobial resistance and virulence in these isolates. Whole-genome sequencing and pangenome analysis revealed considerable genetic diversity, pathogenicity, and an expanding pangenome in P. aeruginosa. Also, ST235 identified as a globally dominant sequence type. So, there is a critical need for robust infection control measures and antimicrobial stewardship programs to combat the dissemination of highly resistant strains in burn units and beyond. Future research should broaden the scope of genomic surveillance to include diverse healthcare settings and environmental reservoirs across Bangladesh.

Materials and methods

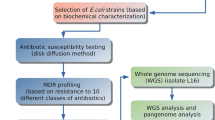

The diagram of the brief methodology of this study is depicted in supplementary Fig. 1.

Sample collection

During 8 months, from October, 2021 to June, 2022; around 110 wound swabs were collected from infected wound of critically injured burn patients who were admitted in Sheikh Hasina National Institute of Burn and Plastic Surgery (SHNIBPS), Dhaka, Bangladesh. Informed consent was obtained from the patients. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The experimental protocols and ethical permission for the study were approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Faculty of Biological Sciences, University of Dhaka (Ref. No. 191/Biol. Scs.). The samples were collected during two different sessions- October–November, 2021 and May–June, 2022. After preliminary analysis, 91 samples were subjected to further analysis. The wound swabs collected from the patients were first cultured on MacConkey agar (MAC) and Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA) plates in the Microbiological Laboratory of SHNIBPS in order to find out the predominating organisms in the sample and also to omit the possibility of biasness. Then the predominant isolated colonies were inoculated on nutrient broth carefully and brought to The Microbial Genetics and Bioinformatics Laboratory, Department of Microbiology, University of Dhaka in a cooler with icepacks (below 4 °C) and processed within a few hours. The organisms were streaked on nutrient agar (NA) plates for the generation of single colonies and preliminary screening was also carried out on cetrimide agar plates.

Cultural and molecular identification

Phenotypic methods were employed for the preliminary identification of the isolate, involving the examination of cultural and morphological traits, along with various biochemical tests53 (Supplementary Table 1). Since our primary focus was on screening for P. aeruginosa, the isolates underwent cultivation on cetrimide agar as an initial step in the cultural screening process. Further, a series of biochemical tests and microscopy were carried out for presumptive identification. On the other hand, rapid molecular approach through PCR based system included genus (oprI) and species (oprL) specific primers (Supplementary Table 2) for the rapid and specific detection of P. aeruginosa54. The DNA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 was used as positive control to validate the results.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing, antimicrobial resistance genes and integron investigation

Antibiotic susceptibility testing for the test isolate was conducted using the Kirby Bauer method55, employing 14 antibiotics recommended for P. aeruginosa in accordance with the CLSI (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2021) guidelines56. In case of colistin, MIC (Minimum Inhibitory Concentration) was carried out in order to find out the antimicrobial susceptibility pattern. Gene specific PCR was carried out for the detection of some major genes responsible for the production of beta lactamase which confer resistance to beta lactams. According to the Amber classification57, there are mainly four classes of beta lactamases. In this study, we have tried to detect some particular pre-targeted genes (Supplementary Table 2) from each class in order to investigate their occurrence. We conducted PCR under specified conditions, adhering to the defined annealing temperature for each primer (Supplementary Table 2). In this study, the existence or occurrence of class I integron in the isolates were investigated. For detecting the presence of class I integons, PCR using specific primers (Supplementary Table 2) was carried out.

Biofilm formation assay and associated genes investigation

The biofilm-forming capacity of the isolates was evaluated using the crystal violet biofilm formation assay (CV assay)58. All samples were cultured in Luria broth medium at 37 °C with shaking for 24 h, followed by a 100-fold dilution in Luria broth. After that, 100 µL of a diluted culture of the test isolate was introduced into Thermo Scientific™ 96-Well Microtiter Microplates. The diluted samples were incubated on plates under static conditions at 37 °C for 24 h. Following the incubation period, planktonic cells were then removed, and the wells containing biofilms were washed three times with distilled water. After drying, the biofilm was treated with 125 μL of a 0.1% crystal violet solution in water. To quantify the extent of biofilm formation, UV absorbance at 600 nm was measured using a microplate reader (GloMax Explorer, Promega), with a 30% acetic acid in water solution serving as the reference. Biofilm formation ability was categorized using the following standard formula: OD ≤ ODcut = Non-biofilm-former,ODcut < OD ≤ 2 × ODcut = Weak biofilm-former, 2 × ODcut < OD ≤ 4 × ODcut = Moderate biofilm-former, OD > 4 × ODcut = Strong biofilm-former and ODcut = ODavg (average of OD’s) of negative control + 3 × standard deviation of ODs of negative control. Here OD means optical density of the samples in CV assay. The biofilm associated genes pelB, pilT, and rhlB were detected for the screening for genes relevant to biofilms through gene specific PCR. The details about the primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Efflux pump associated genes investigation

Several efflux pump genes and related operons are responsible for conferring resistance to a wide range of antibiotics in P. aeruginosa. Among those the resistance-nodulation-division (RND) family of efflux pumps, which exist as a tripartite system and contain a polyspecific substrate binding pocket are the major types. Primer pairs specific for internal mexA, mexC and mexE genes were used to amplify the corresponding genes, for MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ and MexEF-OprN efflux system. The primer sequences and annealing temperature are listed in Supplementary Table 2. PCR products were visualized followed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Whole genome sequencing, assembly and annotation

Two XDR isolate which were collected in two different sessions were subjected to whole genome sequencing and analysis. These two isolates were chosen from two different collection periods, representing the temporal scope of the study. Additionally, both isolates were chosen based on their carbapenem-resistance and strong biofilm-formation pattern, which are significant phenotypic traits associated with persistence and resistance. The DNA of the two selected isolates were extracted using Genomic DNA Purification kit for gram negative bacteria (New England Biolabs, UK) following protocol of Genomic DNA purification from gram negative bacteria (NEB#T3010). The whole genome sequencing of the target isolates was performed under Illumina platform using Illumina Miniseq sequencing system at Bangladesh Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (BCSIR). The generated raw FASTQ files were evaluated for quality through FastQC (v0.11)59. Following that, the adapter sequences and low quality ends per reading were trimmed using Trimmomatic (v0.39)60. After trimming, the high-quality reads were subjected to de novo assembly using SPAdes v3.15.461. After assembly, scaffolding was carried out through Multi-CSAR tool62 using multiple reference genomes. Completeness of the scaffolded genome was checked using CheckM63. The scaffolded genomes were undergone annotation through Prokka64, RAST 65, eggNOG66 and Prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline (PGAP)67,68 of NCBI. The graphical map of the circular genomes were generated through Proksee server69. The whole genome sequence based identification of the isolates were carried out using k-mer based algorithm through LINbase server70 and KmerFinder tool of Center for Genomic Epidemiology71. The identification was validated based on ANI (Average Nucleotide Identity). The serotype of the strains were investigated using PAst (v1.0) tool Center for Genomic Epidemiology72.

WGS based antimicrobial resistance genes, efflux pump genes, metal resistance genes and virulence factor genes investigation

Antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) were investigated through CARD Resistance Gene Identifier server73. Additionally, all efflux pump-related genes and operons were investigated through annotated using Prokka64. Metal resistance genes were identified using BacMet74, and virulence factor genes were analyzed with the VFDB tool75. The pathogenicity of the two bacterial isolates towards human hosts was predicted using the PathogenFinder (v1.1) web tool from the Center for Genomic Epidemiology76. Presence of integrons of the two isolates were investigated using IntegronFinder tool77 of the same platform.

Further the worldwide epidemiology and genome-wide analysis of the beta-lactam resistance gene pool included 6,574 (n = 6574) P. aeruginosa whole genomes available in the NCBI78 and BV-BRC79 databases, encompassing the two isolates from this study. Among these, 6,408 (n = 6408) genomes were from human sources (Supplementary Table 10), and 166 genomes (n = 166) were from non-human sources (Supplementary Table 11). The analysis was conducted using good-quality genome sequences, while poor-quality genomes were excluded to ensure the reliability and accuracy of the results. The whole genome sequences were first downloaded in FASTA format. After that, the CARD Resistance Gene Identifier (CARD:RGI) was used to analyze the antimicrobial resistance genes from the genomic data. The default parameters were used during the analysis.

Subsystems analysis, mobile genetic elements and prophage investigation

Subsystems and functional metabolic pathways were analyzed using the RAST and PATRIC servers. The biosynthetic gene clusters were determined through antiSMASH7.0 tool. The MGEs from the isolate’s whole genome were analyzed using the MobileElementFinder tool80 and mobileOG-db81. Phage integration within the bacterial genome was examined using the PHAge Search Tool Enhanced Release (PHASTER)82 and the Prophage Hunter tool83.

Pangenome analysis, pathogenicity profiling and MLST based epidemiological pattern investigation

A pangenome and comparative genome analysis was conducted to assess the diversity of the target strain. This analysis aimed to identify the presence and absence variations (PAVs) of genes or gene families among strains circulating in Bangladesh by analyzing all the whole genomes publicly available from Bangladesh. 12 whole genome sequences were involved in the pangenome analysis including the two target strains of this study. The assembled FASTA files of the genomes were retrieved from BV-BRC79. The genomes were aligned and visualized using Mauve software package84 which does alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome annotation was performed using Prokka64, and the resulting gff3 files were used for pangenome analysis with Roary85, a tool that rapidly builds large scale pan genomes identifying the core and accessory genes. We tried to get a detailed overview of the organism’s pangenome status and to assess the genomic diversity among the Bangladeshi strains. Pathogenicity profiling and prediction of the isolates’ potential to infect human hosts were performed using PathogenFinder (v1.1)76, a web-based tool developed by the Center for Genomic Epidemiology. The resulting data were subsequently analyzed and visualized utilizing the Tidyverse package in RStudio86.

Further, MLST analysis was carried out using MLST 2.0 server87 and PubMLST server88. The genomic epidemiology and global distribution of nine thousand fifty-five (n = 9,055) P. aeruginosa strains, based on their MLST data, were analyzed using PubMLST. A grapetree was constructed to illustrate the relative distribution and prevalence of different sequence types of P. aeruginosa strains.

Data availability

The genome sequence data were submitted in NCBI under the BioProject ID PRJNA1150750. The accession no. of the two isolate Pseudomonas aeruginosa SHNIBPS64 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa SHNIBPS243 are SRR30335767 and SRR30335766 respectively. Besides, the other genomes used for secondary analysis were retrieved from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and BV-BRC (https://www.bv-brc.org/)

Change history

22 September 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19576-5

References

Mulatu, D., Zewdie, A., Zemede, B., Terefe, B. & Liyew, B. Outcome of burn injury and associated factor among patient visited at Addis Ababa burn, emergency and trauma hospital: A 2 years hospital-based cross-sectional study. BMC Emerg. Med. 22, 199 (2022).

Qin, S. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Pathogenesis, virulence factors, antibiotic resistance, interaction with host, technology advances and emerging therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 7, 199 (2022).

Mondol, S. M. et al. Unveiling a high-risk epidemic clone (ST 357) of ‘difficult to treat extensively drug-resistant’ (DT-XDR) Pseudomonas aeruginosa from a burn patient in Bangladesh: A resilient beast revealing coexistence of four classes of beta lactamases. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 36, 83–95 (2024).

Diggle, S. P. & Whiteley, M. Microbe profile: Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Opportunistic pathogen and lab rat. Microbiology 166, 30–33 (2020).

Kunz Coyne, A. J., El Ghali, A., Holger, D., Rebold, N. & Rybak, M. J. Therapeutic strategies for emerging multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Dis. Ther. 11, 661–682 (2022).

Kamal, S. et al. Risk factors and clinical characteristics of Pandrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Cureus 16, e58114 (2024).

Awanye, A. M. et al. Multidrug-resistant and extremely drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in clinical samples from a tertiary healthcare facility in Nigeria. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 19, 447–454 (2022).

Sathe, N. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Infections and novel approaches to treatment “Knowing the enemy” the threat of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and exploring novel approaches to treatment. Infect. Med. 2, 178–194 (2023).

Pachori, P., Gothalwal, R. & Gandhi, P. Emergence of antibiotic resistance Pseudomonas aeruginosa in intensive care unit; a critical review. Genes Dis. 6, 109–119 (2019).

Gonzalez, M. R. et al. Effect of human burn wound exudate on pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence. mSphere 1, 10–1128 (2016).

Norbury, W., Herndon, D. N., Tanksley, J., Jeschke, M. G. & Finnerty, C. C. Infection in Burns. Surg. Infect. (Larchmt) 17, 250–255 (2016).

Dabbousi, A. A., Dabboussi, F., Hamze, M., Osman, M. & Kassem, I. I. The emergence and dissemination of multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Lebanon: Current status and challenges during the economic crisis. Antibiotics 11, 687 (2022).

Zhang, S., Liao, X., Ding, T. & Ahn, J. Role of β-lactamase inhibitors as potentiators in antimicrobial chemotherapy targeting gram-negative bacteria. Antibiotics https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13030260 (2024).

Muteeb, G., Rehman, M. T., Shahwan, M. & Aatif, M. Origin of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance, and their impacts on drug development: A narrative review. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 16, 1615 (2023).

Mirghani, R. et al. Biofilms: Formation, drug resistance and alternatives to conventional approaches. AIMS Microbiol. 8, 239–277 (2022).

Singh, S., Datta, S., Narayanan, K. B. & Rajnish, K. N. Bacterial exo-polysaccharides in biofilms: Role in antimicrobial resistance and treatments. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 19, 140 (2021).

Zhao, X., Yu, Z. & Ding, T. Quorum-sensing regulation of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria. Microorganisms 8, 425 (2020).

Gaurav, A., Bakht, P., Saini, M., Pandey, S. & Pathania, R. Role of bacterial efflux pumps in antibiotic resistance, virulence, and strategies to discover novel efflux pump inhibitors. Microbiology 169, 001333 (2023).

Sabbagh, P., Rajabnia, M., Maali, A. & Ferdosi-Shahandashti, E. Integron and its role in antimicrobial resistance: A literature review on some bacterial pathogens. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 24, 136–142 (2021).

Yalda, M. et al. Distribution of class 1–3 integrons in carbapenem-resistant pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from inpatients in Shiraz, South of Iran. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 31, 719–724 (2021).

Munita, J. M. & Arias, C. A. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Microbiol. Spectr. 4 (2016).

Hafiz, T. A. et al. Epidemiological, microbiological, and clinical characteristics of multi-resistant pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates in king Fahad Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 8, 205 (2023).

Reynolds, D. & Kollef, M. The epidemiology and pathogenesis and treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections: An update. Drugs 81, 2117–2131 (2021).

Finton, M. D., Meisal, R., Porcellato, D., Brandal, L. T. & Lindstedt, B.-A. Whole genome sequencing and characterization of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacterial strains isolated from a Norwegian University campus pond. Front. Microbiol. 11, 1273 (2020).

Mark, M. S., Aziz, H. M. & Monjurul, H. F. K. Draft genome analysis of a serum-resistant and fourth-generation cephalosporin (cefepime)-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strain TDU5 isolated from Dhaka, Bangladesh. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 14, e01332-e1424 (2025).

Mondol, S. M., Hossain, M. A. & Haque, F. K. M. Comprehensive genomic insights into a highly pathogenic clone ST656 of mcr8.1 containing multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae from Bangladesh. Sci. Rep. 15, 5909 (2025).

Islam, I. et al. Epidemiological pattern and genomic insights into multidrug-resistant ST 491 Acinetobacter baumannii BD20 isolated from infected wound in Bangladesh: Concerning co-occurrence of three classes of beta lactamase genes. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2024.07.009 (2024).

Islam, M. R. et al. First report on comprehensive genomic analysis of a multidrug-resistant Enterobacter asburiae isolated from diabetic foot infection from Bangladesh. Sci. Rep. 15, 424 (2025).

Mondol, S. M. et al. Genomic landscape of NDM-1 producing multidrug-resistant Providencia stuartii causing burn wound infections in Bangladesh. Sci. Rep. 14, 2246 (2024).

Gilchrist, C. A., Turner, S. D., Riley, M. F., Petri, W. A. J. & Hewlett, E. L. Whole-genome sequencing in outbreak analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28, 541–563 (2015).

Bianconi, I., Aschbacher, R. & Pagani, E. Current uses and future perspectives of genomic technologies in clinical microbiology. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland) 12, 1580 (2023).

Saha, K. et al. Isolation and characterisation of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa from hospital environments in tertiary care hospitals in Dhaka, Bangladesh. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 30, 31–37 (2022).

Nath, P. D., Chowdhury, R., Dhar, K., Dhar, T. & Dutta, S. Isolation and Identification of Multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Burn Wound Infection in Chittagong City, Bangladesh. IOSR J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. 12, 43–47 (2017).

Martak, D. et al. High prevalence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa carriage in residents of French and German long-term care facilities. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 28, 1353–1358 (2022).

Zhao, L. et al. High prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and identification of a novel VIM-type metallo-β-lactamase, VIM-92, in clinical isolates from northern China. Front. Microbiol. 16, 1–10 (2025).

Davane, M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa from hospital environment. J. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 4, 42–43 (2014).

Litwin, A., Rojek, S., Gozdzik, W. & Duszynska, W. Pseudomonas aeruginosa device associated: Healthcare associated infections and its multidrug resistance at intensive care unit of University Hospital: Polish, 8.5-year, prospective, single-centre study. BMC Infect. Dis. 21, 180 (2021).

Salmon-Rousseau, A. et al. Comparative review of imipenem/cilastatin versus meropenem. Méd. Mal. Infect. 50, 316–322 (2020).

Verwaest, C. Meropenem versus imipenem/cilastatin as empirical monotherapy for serious bacterial infections in the intensive care unit. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 6, 294–302 (2000).

Farshadzadeh, Z., Khosravi, A. D., Alavi, S. M., Parhizgari, N. & Hoveizavi, H. Spread of extended-spectrum β-lactamase genes of blaOXA-10, blaPER-1 and blaCTX-M in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from burn patients. Burns 40, 1575–1580 (2014).

Tchakal-Mesbahi, A., Metref, M., Singh, V. K., Almpani, M. & Rahme, L. G. Characterization of antibiotic resistance profiles in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from burn patients. Burns 47, 1833–1843 (2021).

Avakh, A., Grant, G. D., Cheesman, M. J., Kalkundri, T. & Hall, S. The art of war with Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Targeting mex efflux pumps directly to strategically enhance antipseudomonal drug efficacy. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland) 12, 1304 (2023).

Geiger, C. J. & O’Toole, G. A. Evidence for the Type IV Pili Retraction Motor PilT as a Component of the Surface Sensing System in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. bioRxiv : The preprint server for biology at https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.02.539127 (2023).

Wittgens, A. et al. Novel insights into biosynthesis and uptake of rhamnolipids and their precursors. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 101, 2865–2878 (2017).

Uruén, C., Chopo-Escuin, G., Tommassen, J., Mainar-Jaime, R. C. & Arenas, J. Biofilms as promoters of bacterial antibiotic resistance and tolerance. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland) 10, 3 (2020).

Glen, K. A. & Lamont, I. L. β-lactam resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Current status, future prospects. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland) 10, 1638 (2021).

Elfadadny, A. et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Navigating clinical impacts, current resistance trends, and innovations in breaking therapies. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1374466 (2024).

Verdial, C., Serrano, I., Tavares, L., Gil, S. & Oliveira, M. Mechanisms of antibiotic and biocide resistance that contribute to Pseudomonas aeruginosa persistence in the hospital environment. Biomedicines https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11041221 (2023).

Pang, Z., Raudonis, R., Glick, B. R., Lin, T.-J. & Cheng, Z. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Mechanisms and alternative therapeutic strategies. Biotechnol. Adv. 37, 177–192 (2019).

Urban-Chmiel, R. et al. Antibiotic resistance in bacteria: A review. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland) 11, 1079 (2022).

Lorusso, A. B., Carrara, J. A., Barroso, C. D. N., Tuon, F. F. & Faoro, H. Role of efflux pumps on antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 15779 (2022).

Dey, S. et al. Unravelling the evolutionary dynamics of high-risk Klebsiella pneumoniae ST147 clones: Insights from comparative pangenome analysis. Genes (Basel) 14, 1037 (2023).

Roy, B., Das, T. & Bhattacharyya, S. Overview on old and new biochemical test for bacterial identification. Scholast. Microbiol. 1, 2–7 (2023).

Gholami, A., Majidpour, A., Talebi-Taher, M., Boustanshenas, M. & Adabi, M. PCR-based assay for the rapid and precise distinction of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from other Pseudomonas species recovered from burns patients. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 57, E81–E85 (2016).

Hudzicki, J. Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion susceptibility test protocol author information. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 15(1), 1–23 (2012).

Magiorakos, A.-P. et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18, 268–281 (2012).

Bush, K. & Jacoby, G. A. Updated functional classification of beta-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 969–976 (2010).

O’Toole, G. A. Microtiter dish biofilm formation assay. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/2437 (2011).

Ward, C. M., To, T. H. & Pederson, S. M. NgsReports: A bioconductor package for managing FastQC reports and other NGS related log files. Bioinformatics 36, 2587–2588 (2020).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Bankevich, A. et al. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19, 455–477 (2012).

Liu, S.-C., Ju, Y.-R. & Lu, C. L. Multi-CSAR: A web server for scaffolding contigs using multiple reference genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, W500–W509 (2022).

Parks, D. H., Imelfort, M., Skennerton, C. T., Hugenholtz, P. & Tyson, G. W. CheckM: Assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 25, 1043–1055 (2015).

Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30, 2068–2069 (2014).

Aziz, R. K. et al. The RAST server: Rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 15, 1–15 (2008).

Hernández-Plaza, A. et al. eggNOG 6.0: Enabling comparative genomics across 12 535 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D389–D394 (2023).

Tatusova, T. et al. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 6614–6624 (2016).

Li, W. et al. RefSeq: Expanding the prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline reach with protein family model curation. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 1020–1028 (2021).

Grant, J. R. et al. Proksee: in-depth characterization and visualization of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, W484–W492 (2023).

Tian, L., Huang, C., Mazloom, R., Heath, L. S. & Vinatzer, B. A. LINbase: A web server for genome-based identification of prokaryotes as members of crowdsourced taxa. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, W529–W537 (2020).

Kirstahler, P. et al. Genomics-based identification of microorganisms in human ocular body fluid. Sci. Rep. 8, 4126 (2018).

Thrane, S. W., Taylor, V. L., Lund, O., Lam, J. S. & Jelsbak, L. Application of Whole-genome sequencing data for O-specific antigen analysis and in silico serotyping of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 54, 1782–1788 (2016).

McArthur, A. G. et al. The comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 3348–3357 (2013).

Pal, C., Bengtsson-Palme, J., Rensing, C., Kristiansson, E. & Larsson, D. G. J. BacMet: Antibacterial biocide and metal resistance genes database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D737–D743 (2014).

Chen, L. et al. VFDB: A reference database for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 325–328 (2005).

Cosentino, S., Voldby Larsen, M., Møller Aarestrup, F. & Lund, O. PathogenFinder: Distinguishing friend from foe using bacterial whole genome sequence data. PLoS ONE 8, e77302 (2013).

Néron, B. et al. IntegronFinder 2.0: Identification and analysis of integrons across bacteria, with a focus on antibiotic resistance in Klebsiella. Microorganisms 10, 700 (2022).

O’Leary, N. A. et al. Reference sequence (RefSeq) database at NCBI: Current status, taxonomic expansion, and functional annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D733–D745 (2016).

Olson, R. D. et al. Introducing the bacterial and viral bioinformatics resource center (BV-BRC): A resource combining PATRIC, IRD and ViPR. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D678–D689 (2023).

Durrant, M. G., Li, M. M., Siranosian, B. A., Montgomery, S. B. & Bhatt, A. S. A Bioinformatic analysis of integrative mobile genetic elements highlights their role in bacterial adaptation. Cell Host Microbe 27, 140-153.e9 (2020).

Brown, C. L. et al. mobileOG-db: A manually curated database of protein families mediating the life cycle of bacterial mobile genetic elements. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 88, e00991-e1022 (2022).

Arndt, D. et al. PHASTER: A better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W16-21 (2016).

Song, W. et al. Prophage hunter: An integrative hunting tool for active prophages. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W74–W80 (2019).

Darling, A. C. E., Mau, B., Blattner, F. R. & Perna, N. T. Mauve: Multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 14, 1394–1403 (2004).

Page, A. J. et al. Roary: Rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics 31, 3691–3693 (2015).

Wickham, H. et al. Welcome to the tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1686 (2019).

Larsen, M. V. et al. Multilocus sequence typing of total-genome-sequenced bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 1355–1361 (2012).

Jolley, K. A., Bray, J. E. & Maiden, M. C. J. Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res. 3, 124 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of Tasnia Nuzhat and Rashna Sharmeen Shama in sample collection and processing. We would like to thank Department of Microbiology, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh for providing the platform to conduct the research work.

Funding

This work has received funding from the University Grants Commission(UGC) of Bangladesh.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M.R., M.R.I. and S.M.M. developed the hypothesis and designed the study. S.M.M., M.I.M., M.H.H. and S.K.S. carried out the laboratory experiments. M.R.I., I.I., and N.N.R. assisted in laboratory experiments. S.M.M. performed the whole genome sequence analysis and computational analysis. M.R.I., F.F., K.A. assisted in the computational analysis. S.M.M. prepared the first draft of the manuscript. M.M.R, I.I., N.N.R., M.R.I., S.K.S, J.F.M. and A. critically reviewed the manuscript. M.M.R. supervised the whole study. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Ethical permission to conduct the experimental protocols was given and verified by the Ethical Review Committee of Faculty of Biological Sciences, University of Dhaka (Ref. No. 191/Biol. Scs.). We confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was taken from the patients for sample collection, conduct research with the samples and to publish the outcome.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: An outdated version of Figure 5 was published in the original version of this Article. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mondol, S.M., Islam, M.R., Mia, M.E. et al. Molecular and genomic insights into multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) Pseudomonas aeruginosa causing burn wound infections in Bangladesh. Sci Rep 15, 25445 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11614-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11614-6