Abstract

The prognostic value of the glucose-potassium ratio (GPR) in non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) remains undetermined. We investigated the association between the GPR at admission and all-cause mortality (ACM) in critically ill patients with SAH. We identified critically ill patients with SAH from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care database and stratified them into quartiles based on the GPR levels at admission. To evaluate mortality risk associations, we employed Cox proportional hazards models along with restricted cubic splines (RCS) to assess non-linear relationships. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier (K–M) method. The robustness of the results was assessed through prespecified subgroup analyses and interaction tests, with effect modifications evaluated using likelihood ratio testing. The study cohort comprised 855 patients (median age: 61 years), with cumulative ACM rates of 18.5% at 30 days, 22.7% at 90 days, and 26.4% at 1 year. Cox regression analysis results revealed that higher GPR was significantly related to ACM at 30 days (hazard ratio (HR): 1.42; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.13–1.80), 90 days (HR: 1.31; 95% CI 1.05–1.64), and 1 year (HR: 1.25; 95% CI 1.00–1.54). RCS analysis revealed a non-linear U-shaped association with an inflection point at GPR = 2.3. Below this threshold, GPR revealed no mortality association (HR: 0.96, 95% CI 0.57–1.63), while values above exhibited progressive risk elevation (HR: 1.67, 95% CI 1.25–2.22). Subgroup analyses confirmed consistent associations across patient characteristics (all interactions, p > 0.05). Moreover, the combination of GPR and GCS performed better than GPR and GCS alone in predicting ACM. A U-shaped relationship was found between GPR and mortality in critically ill patients with SAH. This easily available biomarker holds potential for risk stratification and clinical decision-making, though optimal thresholds require prospective validation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), primarily caused by aneurysmal rupture, is the third most common subtype of stroke1. Annually, nearly 500,000 individuals suffer from SAH2. Despite therapeutic advances, early mortality remains high, 25% of patients with SAH die before or during emergency care340% at 30 days4and 50% at 1 year4. Given the high mortality rate associated with SAH, it is crucial to identify a simple, time-saving, and readily available prognostic predictor to stratify patients at increased risk of adverse clinical outcomes5. Currently, several clinical scales, such as the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies (WFNS) grade and the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), are widely used and have been reported to correlate with functional prognosis. However, these scales also suffer from inherent limitations, including an overreliance on clinical symptoms and imaging findings6. Furthermore, their application is limited in specific clinical scenarios, such as sedated and mechanically ventilated patients7.

Biomarkers on admission can reflect changes in patients’ neurological and physical conditions, thereby enabling the optimization of their treatment8. Compared to traditional scales, biomarkers offer a broader range of applications and are easier to quantify. Previous studies have demonstrated the potential of biomarkers as valuable tools for assessing disease risk and predicting prognosis. For instance, serum C-reactive protein levels and the glucose-phosphate ratio can predict prognosis, while the platelet-Ca²⁺ ratio and neutrophil-albumin ratio can predict complications9,10,11,12. Interestingly, the clinical utility of combined biomarker panels as both risk assessment tools and predictive biomarkers is increasingly recognized. These panels typically integrate parameters that exhibit correlated yet opposing changes during disease progression, allowing them to capture complementary pathological processes. Consequently, combined biomarkers often demonstrate superior sensitivity and clinical representativeness compared to isolated single markers13.

Serum potassium and glucose levels are common and cost-effective biomarkers. Stress hyperglycemia has been demonstrated associated with poor clinical outcomes in SAH14. Hypokalemia has also been reported to be the most common electrolyte disorder after SAH and is often combined with other clinical parameters as a predictor of poor prognosis and complications with SAH13. Moreover, previous research has highlighted a strong connection between potassium and glucose metabolism15. The potential interaction between serum glucose and potassium levels has led to the introduction of the glucose-potassium ratio (GPR). Emerging evidence highlights GPR as a promising prognostic marker across neurocritical conditions, including traumatic brain injury16ischemic stroke15and intracerebral hemorrhage17. Several studies have reported a significant association between GPR, cerebral vasospasm, and functional outcome6,18,19. Furthermore, a multicenter randomized controlled trial found a J-shaped relationship between GPR and prognosis in patients with heart failure20revealing the possibility of a nonlinear relationship between the GPR and clinical outcomes. Although GPR has been found to be related to the clinical outcomes of patients in many researches, no study has yet explored the relationship between GPR and prognosis in the critically ill patients with SAH. Currently, only Matano et al. have reported that the GPR in SAH is significantly associated with cerebral infarction due to cerebral vasospasm19.

To address this gap, we used the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC-IV) database to evaluate GPR’s prognostic utility of GPR for the mortality risk stratification of SAH. Our study aimed to clarify the relationship between admission GPR and all-cause mortality (ACM), with the ultimate goal of optimizing risk assessment and targeted ICU management for this vulnerable population.

Methods

Study population

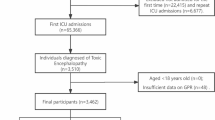

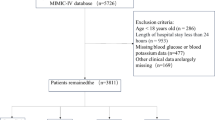

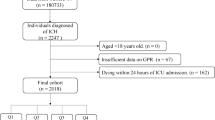

This retrospective cohort study utilized data from the MIMIC-IV database (version 2.2), a publicly accessible repository of de-identified clinical records from patients admitted to the ICUs of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center between 2008 and 201921. One of the authors, Jianyi Liu (Record ID: 12912699), who met the database access requirements, performed data extraction. Adult patients (≥ 18 years) with non-traumatic SAH were identified using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes (ICD-9:430; ICD-10: I60). Exclusion criteria included repeated ICU admissions (only the first SAH-related admission was retained), mortality within 24 h of ICU admission, and missing glucose or potassium measurements on the first day of ICU admission. Finally, 855 patients were included in this study (Fig. 1). Ethical approval was waived because the MIMIC-IV database received prior approval from the institutional review boards of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, with all patient data anonymized.

Data collection

Collected data included demographic characteristics (age and sex), clinical parameters (average vital signs and laboratory results within the first 24 h of ICU admission), disease severity scores (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS-II)), comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, and heart failure), and survival outcomes (30-day, 90-day, and 1-year mortality). GPR was calculated as the ratio of admission glucose (mmol/L) to potassium (mmol/L) levels. Variables or patients with > 20% missing data were excluded, and remaining missing values were imputed using multivariate chained equations via the R “mice” package22.

Clinical outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was 30-day ACM, with secondary outcomes included 90-day and 1-year ACM.

Statistical analysis

Patients were stratified into quartiles (Q1–Q4) based on their admission GPR. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range (IQR)) and compared using Student’s t-test, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, or one-way ANOVA, depending on data distribution. Categorical variables are reported as frequencies (percentages) and analyzed via χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests. Survival differences across GPR quartiles were evaluated using Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests. Cox proportional hazard models were used to quantify the associations between GPR and mortality using hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Three sequential models were constructed: Model 1 (unadjusted), Model 2 (adjusted for age and sex), and Model 3 (adjusted for covariates identified through stepwise regression, including SAPS-II score, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, heart and respiratory rate, SPO2, mechanical ventilation, sepsis, blood pressure, hemoglobin, white blood cell count, platelet count, creatinine, hepatic disorders, diabetes, malignant neoplasms, and Charlson Comorbidity Index). The GPR was analyzed both as a continuous and ordinal variable (quartiles, Q1 as the reference). The restricted cubic splines (RCS) curve analysis revealed a non-linear relationship between GPR and mortality. The optimal cut-off point for the non-linear relationship between GPR and mortality was determined using the R package “CatPredi”. A threshold effect analysis of GPR on the risk of death was performed using COX proportional hazard models. Subgroup analyses stratified by age, sex, and comorbidities were further tested for these associations. Additionally, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was conducted to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity. The area under the curve (AUC) was then calculated to assess the predictive performance. All statistical analyses were conducted using R v4.2.2, with statistical significance set as a two-tailed p < 0.05.

Patient and public involvement

None.

Results

Baseline characteristics of enrolled patients

A total of 855 patients with a median age of 61 years (IQR: 51–73) and 377 males (44.1%) were enrolled in the study. Patients were stratified into four groups based on admission GPR level (Q1: 0.58–<1.59; Q2: 1.59–<1.90; Q3: 1.90–<2.28; Q4: 2.28–5.91), with corresponding median GPR values of 1.41 (IQR: 1.30–1.49), 1.75 (1.69–1.81), 2.06 (1.97–2.15), and 2.67 (2.45–3.00) (Table 1). The overall mortality rates were 18.5% at 30 days, 22.7% at 90 days, and 26.4% at 1 year. Patients in the highest GPR quartile (Q4) exhibited distinct clinical profiles, including older age, higher illness severity scores, elevated white blood cell counts, increased prevalence of sepsis and diabetes, greater use of mechanical ventilation, and higher mortality rates across all-time points than those in the lower quartiles.

Primary outcome

Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed a graded association between GPR quartiles and mortality, with Q4 revealing the highest risk of 30-day, 90-day, and 1-year ACM (Fig. 2). Cox regression models revealed that continuous GPR elevation independently predicted 30-day ACM (HR: 1.42, 95% CI 1.13–1.80), though this association attenuated in fully adjusted categorical analyses (Model 3). Similar trends were observed for 90-day and 1-year outcomes (Table 2). Restricted cubic splines analysis revealed a non-linear U-shaped relationship between GPR and ACM, with an inflection point at GPR = 2.3. Below this threshold, GPR revealed no mortality association (HR: 0.96, 95% CI 0.57–1.63), whereas values above 2.3 conferred progressively higher risk (HR: 1.67, 95% CI 1.25–2.22), as depicted in Fig. 3; Table 3. ROC curves of GPR, GCS, and their combination are plotted in Fig. 4. The combination of GPR and GCS performed better than GPR and GCS alone in predicting ACM.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses identified heightened 30-day ACM risk associated with elevated GPR in males (HR: 1.55, 95% CI 1.08–2.22), patients aged ≤ 65 years (HR: 1.65, 95% CI 1.13–2.42), those with diabetes (HR: 2.40, 95% CI 1.41–4.10), and mechanically ventilated individuals (HR: 1.58, 95% CI 1.23–2.02). These trends persisted consistently across 90-day and 1-year ACM analyses (Fig. 5).

Discussion

This study found a significant association between elevated admission GPR and increased short- and long-term ACM in critically ill patients with SAH, which is consistent with prior evidence6,18. Furthermore, subgroup analyses confirmed the robustness of this association across key demographic and clinical strata. These findings underscore GPR’s utility as a pragmatic prognostic marker, particularly in severe SAH cases6. Notably, the results from the ordinal Model 3 are inconsistent with the continuous one. There may be two possible explanations for this discrepancy. Firstly, in this study, we identified a novel non-linear relationship characterized by a U-shaped curve (inflection point: GPR = 2.3), where mortality risk increases substantially above this threshold (HR: 1.67, 95% CI 1.25–2.22) but reveals no association below it (HR: 0.96, 95% CI 0.57–1.63). Secondly, the highest GPR quartile (Q4) had a notably higher proportion of diabetic patients. Insulin deficiency/resistance can elevate glucose and impair potassium uptake, potentially inflating measured GPR values in this group. Consequently, the apparent association in Model 3 was attenuated after adjusting for diabetes.

Hyperglycemia and hypokalemia are common complications in patients with SAH, often arising from secondary cerebral ischemia and sympathetic nervous system overactivation following aneurysm rupture23,24. The underlying pathophysiology involves catecholamine-induced sympathetic overactivation, leading to excessive production of epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine25. Elevated catecholamine levels overactivated the Na+/K+-ATPase pump, causing potassium ion shift from the extracellular to intracellular compartments26. Epidemiological data have revealed hypokalemia incidence rates of 43.7–65.5% and hyperkalemia rates of 1.3–5.7% in patients with craniocerebral disease27,28. However, the prognostic significance of potassium imbalance in SAH remains controversial. Alimohamadi et al. found that subacute-phase hypokalemia (days 7–10) correlated with poor outcomes, while hyperkalemia revealed inverse radiographic severity associations29. Conversely, Tam et al. found no significant prognostic impact of either electrolyte disturbance30. This controversy may stem from complex pathophysiological mechanisms. Catecholamine-mediated hyperglycemia stimulates insulin secretion and promotes cellular potassium uptake31,32. Hyperglycemia itself is independently correlated with initial neurological deficits and 6-month unfavorable outcomes33. Notably, patients with persistent hyperglycemia exhibit a seven-fold increased risk of poor prognosis compared to normoglycemic individuals34. A study by Uijtendaal et al. revealed a bimodal mortality pattern; intensive care patients with low glucose/high potassium or high glucose/low potassium combinations exhibited the highest mortality35. These findings suggest that serum glucose and potassium displayed a complex interplay and proposed a profound effect of potassium on the maintenance of glucose homeostasis. Therefore, GPR maybe a more comprehensive index with a better predictive ability in comparison to the simple serum glucose or serum potassium.

In previous studies, GPR has been reported as an independent predictor for increased 30-day mortality363-month mortality18 and preoperative rebleeding risk37. Additionally, a Japanese cohort using the Hunt-Kosnik grading system found a significantly higher GPR in patients with severe SAH6. And these findings suggested that clinicians should consider monitoring both glucose and potassium levels collectively rather than in isolation. In our study, the superior discriminative ability of GPR compared to isolated measurements (as demonstrated by ROC curve analysis) also highlighted its potential value as an integrated biomarker for risk stratification in clinical practice. Furthermore, the combination of GPR and GCS also performed better predictive performance than GPR and GCS alone in predicting ACM. Notably, GPR exhibited a U-shaped relationship with ACM, which means that both excessively high or low GPR levels are positively associated with increasing ACM. An elevated GPR may indicate hyperglycemia and hypokalemia, while a reduced GPR may reflect hypoglycemia and hyperkalemia, which both heighten the risk for mortality35. Given the predictive utility of GPR, clinical strategies targeting maintenance of GPR near the established critical threshold (2.3) may optimize prognostic outcomes for SAH patients. This approach enables early identification of high-risk individuals through biomarker monitoring, facilitating timely therapeutic interventions and tailored management protocols. For example, high-risk patients with GPR significantly deviating from 2.3 require intensive monitoring protocols to proactively mitigate risks of vascular spasm and recurrent hemorrhage. Such proactive clinical strategies could potentially mitigate disease progression by addressing metabolic imbalances, thereby improving functional recovery and reducing mortality risks in SAH patients. Conversely, patients exhibiting GPR values near the 2.3 threshold may transition to less frequent surveillance regimens, enabling more efficient allocation of clinical resources while maintaining appropriate oversight. This tiered monitoring strategy balances preventative care for metabolically unstable patients with healthcare resource optimization. Future research is also required to elucidate a proper cutoff range of GPR in SAH patients for a better prognosis and explore its combined predictive value with clinical scales, such as GCS and Hess-Hunt.

The strengths of this study include robust confounder adjustment and the novel identification of a GPR mortality threshold in a U.S. critical care cohort. However, a few limitations must be acknowledged. First, the retrospective design precludes causal inference, and unmeasured confounders (e.g., SAH onset timing and exact causes of mortality) may persist despite multivariable adjustments. Second, GPR was assessed only at admission; dynamic fluctuations during hospitalization, which are potentially more prognostically relevant, were not explored. Third, the single-center data limit generalizability, necessitating validation in diverse populations. Fourth, due to the nature of the MIMIC-IV database, detailed information on patient-level interventions (e.g., specific drug regimens or surgical techniques) was unavailable. Although we adjusted for available clinical covariates and institutional factors, residual confounding may exist if treatments were differentially administered across comparison groups. Future research should address these limitations and build on the current findings.

Conclusion

Higher levels of GPR were associated with an increased risk of death in critically ill patients with SAH, and the relationship between GPR and mortality exhibited a U-shaped curve. Our findings provide preliminary evidence on metabolic derangements in SAH and generate the hypothesis that GPR may serve as a clinical indicator. Given the inherent limitations of the study design, these results require rigorous validation in prospective, multicenter studies to assess the temporal dynamics of GPR and to refine optimal clinical thresholds.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found at https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/3.1/.

References

Claassen, J. & Park, S. Spontaneous subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet 400(10355), 846–862 (2022).

Hughes, J. D. et al. Estimating the global incidence of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A systematic review for central nervous system vascular lesions and Meta-Analysis of ruptured aneurysms. World Neurosurg. 115, 430–447e7 (2018).

Korja, M., Lehto, H., Juvela, S. & Kaprio, J. Incidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage is decreasing together with decreasing smoking rates. Neurology 87(11), 1118–1123 (2016).

Lichtman, J. H. et al. 30-day mortality and readmission after hemorrhagic stroke among medicare beneficiaries in joint commission primary stroke center-certified and noncertified hospitals. Stroke 42(12), 3387–3391 (2011).

Megjhani, M. et al. Dynamic detection of delayed cerebral ischemia: A study in 3 centers. Stroke 52(4), 1370–1379 (2021).

Fujiki, Y. et al. Serum glucose/potassium ratio as a clinical risk factor for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Neurosurg. 129(4), 870–875 (2018).

Fung, C. et al. Reconsidering the logic of world federation of neurosurgical societies grading in patients with severe subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Neurosurg. 124(2), 299–304 (2016).

Zhou, H., Tang, Y., Li, Y. & Zhu, T. Serum glucose-potassium ratio predicts prognosis of traumatic brain injury in patients undergoing emergency craniotomy: A retrospective study. Asian J. Surg. 46(7), 2958–2959 (2023).

Zhang, D. et al. Association of admission serum glucose-phosphate ratio with severity and prognosis of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. World Neurosurg. 127, e1145–e1151 (2019).

Qiu, S. Z. et al. Prognostic value of admission serum glucose-phosphate ratio in predicting the 6-month outcome of patients with severe traumatic brain injury: A retrospective study. Clin. Chim. Acta 510, 659–664 (2020).

Fountas, K. N. et al. Serum and cerebrospinal fluid C-reactive protein levels as predictors of vasospasm in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Clinical Article. Neurosurg. Focus. 26(5), E22 (2009).

Wang, X. T. & Xu, Y. H. Platelets-to-serum Ca2 + ratio as a risk factor for postoperative cerebral vasospasm in surgically treated aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage patients. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 26(5), 1439–1449 (2022).

Li, W. et al. Predictive value of fibrin fibrinogen degradation products-to-potassium ratio for poor functional outcome in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A retrospective case-control study. Neurocrit Care 40(3), 1013–1024 (2024).

Schlenk, F., Vajkoczy, P. & Sarrafzadeh, A. Inpatient hyperglycemia following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: Relation to cerebral metabolism and outcome. Neurocrit Care 11(1), 56–63 (2009).

Lu, Y., Ma, X., Zhou, X. & Wang, Y. The association between serum glucose to potassium ratio on admission and short-term mortality in ischemic stroke patients. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 8233 (2022).

Zhou, J. et al. Usefulness of serum glucose and potassium ratio as a predictor for 30-day death among patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Clin. Chim. Acta 506, 166–171 (2020).

Wu, X. Y. et al. Serum glucose and potassium ratio as a predictive factor for prognosis of acute intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Int. Med. Res. 49(4), 3000605211009689 (2021).

Jung, H. M., Paik, J. H., Kim, S. Y. & Hong, D. Y. Association of plasma glucose to potassium ratio and mortality after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Front. Neurol. 12, 661689 (2021).

Matano, F. et al. Serum glucose and potassium ratio as risk factors for cerebral vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 28(7), 1951–1957 (2019).

Shan, L. et al. J-shaped association between serum glucose potassium ratio and prognosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction with stronger predictive value in non-diabetic patients. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 29965 (2024).

Johnson, A. E. W. et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data 10(1), 1 (2023).

van Buuren, S. & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. Mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 45(3), 1–67 (2011).

Dorhout Mees, S. M. et al. Glucose levels and outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology 61(8), 1132–1133 (2003).

Fukui, S. et al. Female gender as a risk factor for hypokalemia and QT prolongation after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology 59(1), 134–136 (2002).

Ogura, T. et al. Characteristics and prognostic value of acute catecholamine surge in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurol. Res. 34(5), 484–490 (2012).

Chen, S. et al. The harmful effects of subarachnoid hemorrhage on extracerebral organs. Biomed. Res. Int. 858496 (2014).

Pin-On, P. et al. Serum electrolyte imbalance and prognostic factors of postoperative death in adult traumatic brain injury patients: A prospective cohort study. Med. (Baltim). 97(45), e13081 (2018).

Ookuma, T. et al. The clinical relevance of plasma potassium abnormalities on admission in trauma patients: A retrospective observational study. J. Intens. Care 3(1), 37 (2015).

Alimohamadi, M. et al. Impact of electrolyte imbalances on the outcome of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A prospective study. Asian J. Neurosurg. 11(1), 29–33 (2016).

Tam, C. W., Shum, H. P. & Yan, W. W. Impact of dysnatremia and dyskalemia on prognosis in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A retrospective study. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 23(12), 562–567 (2019).

Massara, F., Tripodina, A. & Rotunno, M. Propranolol block of epinephrine-induced hypokaliaemia in man. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 10(3), 404–407 (1970).

Reid, J. L., Whyte, K. F. & Struthers, A. D. Epinephrine-induced hypokalemia: The role of beta adrenoceptors. Am. J. Cardiol. 57(12), 23f–27f (1986).

Beseoglu, K. & Steiger, H. J. Elevated glycated hemoglobin level and hyperglycemia after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 163, 128–132 (2017).

McGirt, M. J. et al. Persistent perioperative hyperglycemia as an independent predictor of poor outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Neurosurg. 107(6), 1080–1085 (2007).

Uijtendaal, E. V. et al. Influence of a strict glucose protocol on serum potassium and glucose concentrations and their association with mortality in intensive care patients. Crit. Care 19(1), 270 (2015).

Alışkan, H., Kılıç, M. & Ak, R. Usefulness of plasma glucose to potassium ratio in predicting the short-term mortality of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Heliyon 10(18), e38199 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Elevated Glucose-Potassium ratio predicts preoperative rebleeding in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Front. Neurol. 12, 795376 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank Jun Yang for the assistance.

Funding

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. and Y.G. designed the study. J.L. and Y.L. extracted, collected, and analyzed the data. Y.Y. and J.Z. prepared the tables and figures. J.W. and Z.H. reviewed the results, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed equally to this manuscript and have approved its submission for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Given that the data were accessible to the public through the MIMIC-IV database, the need for ethical approval and informed consent was waived.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, Y., Yang, Y., Zhu, J. et al. The U shape relationship between glucose and potassium ratio and mortality in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage in the US population. Sci Rep 15, 27084 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11630-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11630-6