Abstract

Renewable energy dependence on variable weather creates mismatches with energy demand. One possible solution is to produce and store green hydrogen by energy surpluses for later use. While surface storage options are limited, subsurface storage in salt caverns (200 m to 2 km deep) is more suitable due to their favorable properties. However, imaging these caverns is difficult because traditional geophysical methods often lack the resolution or depth penetration needed, making it challenging to study such formations effectively. Many of the limitations of conventional geophysical prospecting methods can be addressed by Muon Radiography (MR), an advanced technique that uses cosmic muons to detect underground density variations. Because muons penetrate deeply, their attenuation reveals information about the density and structure of the material, allowing for the identification of cavities with high spatial resolution over several hundred meters. This article presents a MR project aimed at imaging and characterizing underground salt caverns in southern Sicily. A muon detector was first installed at the surface to collect a calibration sample of free-sky muons, then moved to an underground gallery at \(-106\) m ASL to test the method near a known tunnel. The paper includes expected results from synthetic data and first data analysis from the calibration and underground samples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Renewable energy sources play a key role in achieving the European Union’s environmental goals set by the Horizon Europe program1. Therefore, developing renewable energy systems that are affordable, reliable, and sustainable is paramount in this process and has recently received increased attention. To ensure system security and flexibility, the storage of excess renewable energy represents an integral component of these energy systems. In high-latitude areas like Europe, renewable energy production varies with season2 and therefore long-term (monthly to seasonal) and large-scale (GWh-TWh) energy storage represents a potential opportunity to reduce seasonal supply and demand imbalances as part of the export supply chain. One proposed strategy to address this issue is converting excess renewable energy into green hydrogen via electrolysis, which can then be stored and reused during periods of high demand. As demand for hydrogen increases, repurposing depleted gas fields, aquifers, and salt caverns can provide a cost-effective and environmentally friendly solution for future large hydrogen storage2. This requires not only investment in both imaging the subsurface but also re-designing the technical hydrogen storage capacity of existing gas storage sites in Europe or re-purposing underground caverns3. A highly promising method is to store hydrogen in salt caverns due to their sealing capacity (permeability ranging from 10\(^{-20}\) \(\hbox {m}^2\) to 10\(^{-22}\) \(\hbox {m}^2\) 4). Salt caverns are artificial underground cavities in salt formation (often pure halite) which ideally are located between 200 meters and 2 km deep. They are considered the most suitable underground storage for managing short- to medium- term fluctuations in hydrogen supply, thanks to their favorable physical and chemical properties5,6. A major challenge in studying onshore subsurface caverns at depth is their limited responsiveness to traditional geophysical imaging techniques, including seismic, electrical resistivity, ground-penetrating radar, magnetotellurics, and gravity modeling methods.

For example, seismic imaging depends on signal frequency and rock impedance7,8,9,10, but the top boundary of salt formations often absorbs a large part of the the signal frequencies reducing image quality during transmission. As for gravity methods, although they are effective for delineating the gross features of a salt dome, they generally lack the resolution to discriminate finer details of salt domes. Modern electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) is an excellent near-surface geophysical tool for delineating resistivity contrasts (conductive brine-filled caverns). However its practical depth limit is typically about 200 m (660 ft), too shallow for delineating most caverns7,8,9,10. As a result, the combination and joint inversion of the aforementioned methodologies may be necessary, and even then, may still be insufficient to image the detailed salt stratigraphy.

Many of the limitations of conventional geophysical prospecting methods can be addressed by Muon Radiography (MR or Muography), an emerging technique that measures the flux of cosmic muons underground. Muons are highly penetrative particles, far more so than X-rays, and their flux decreases as they pass through matter depending on its density and thickness. By analyzing this attenuation, a straightforward inversion method can be used to reconstruct the density distribution of the overlying volume and identify cavities. Muon Radiography is effective over distances of several hundred meters and can achieve spatial resolutions of a few meters. The first known application of MR was by E.P. George, who measured rock overburden above a tunnel11. However, the technique’s foundation is attributed to Nobel laureate L. Alvarez, who used MR to search for hidden chambers in the Chephren’s pyramid12. In recent years, muography has found applications in volcanology, geology, archaeology, mining, and engineering see13,14,15,16 for general reviews and17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24 for more specific cases concerning the detection of underground cavities and the density distributions in mineral exploration. In this article, a project of MR for imaging and characterizing underground salt caverns is presented. The mine is located at the southern coast of Sicily. Initially a muon detector has been installed at the surface of the mine to acquire a calibration sample of free-sky muons. Then the detector was deployed inside a gallery at -106 m ASL in correspondence of a known tunnel at -85 m ASL, used to test the methodology. The expected results obtained by synthetic data are presented, and the first results from the free-sky sample are shown.

The Realmonte salt mine

The geological setting

The designated area for muographic acquisition is located along the southern coast of Sicily between the towns of Realmonte and Siculiana in the province of Agrigento, Italy. This site was identified within the alkaline salt mine of Realmonte, one of the three traditional mines with chambers and galleries still operational on the island. Geologically, the Realmonte site is part of the larger Caltanissetta Basin25 (see Fig. 1), a significant NE-SW trending depression primarily filled with salt deposits from the Mediterranean salinity crisis, resulting from the temporary closure of the Mediterranean Sea from the Strait of Gibraltar between 5.97 and 5.33 million years ago (Messinian age)26, and with more recent sandy, clay, and carbonate deposits (Plio-Pleistocene). Specifically, the Messinian Realmonte salt deposit comprises a 400–600 m thick halite sequence27, beginning with pre-rock salt deposits (older Messinian deposits of predominantly carbonate and clastic nature), followed by an approximately 150–250 m thick layer of pure halite (NaCl), and an 80–120 m thick unit where halite is interbedded with highly deformed and finely stratified K-Mg salt layers (mainly kainite, MgSO4-KCl-3(H2O)), as well as clay layers26,27,28,29,30,31. The third salt unit, approximately 100 m thick, consists of pure halite (represented by the yellow and magenta units in Fig. 1. Above these layers is an overburden unit up to 140 m thick, composed of gypsum, chalk, and clay (blue units in Fig. 1). The large rock salt lens-shaped deposit that hosts the mine is notably deformed by the presence of faults and folds with a NO-SE orientation32,33.

The mine setting

The Realmonte Salt Mine, located 2.5 km from the town of Realmonte in the Contrada Scavuzzo area (Fig. 2), has been operated by Italkali since 1971, primarily for rock-salt extraction. With an annual production exceeding 1 million tons, the mine is a key supplier of industrial and high-quality de-icing salt. It features an extensive network of tunnels and galleries, stretching horizontally over 6 km and vertically from +60 to \(-252\) m above sea level (Fig. 2). The mine includes 16 galleries asymmetrically distributed across two distinct areas to the east and west of Realmonte, separated by a ramp with a gradient of approximately 10% (ranging from \(-30\) m to \(-230\) m ASL.), with a total length of approximately 130 km. The section of the deposit beneath the urban area, where the inclined ramp is located, is not currently mined due to safety concerns, whereas access to the underground is facilitated by a 13.5% inclined conveyor slope for the daily transport of pre-crushed ore. All tunnels are identified by the height of the walkway, with an average width of 22 m and a height varying between 5.60 and 7.50 m, depending on the technical progress of ore extraction. In the eastern section, the galleries were numbered: \(-30, -45, -60, -75, -90, -105, -120\), and \(-135\). In the western section, the galleries are numbered: \(-85, -106, -128, -146, -160, -172, -175\), and \(-195\) (Fig. 2).

(a) Regional location of the Realmonte mining area. Green and orange represent the geodynamic attributes accepted in the literature. Orange represents the area deformed by the presence of the Sicilian-Maghreb chain (on orogen), with green color the undeformed area of the Hyblean Plateau (foreland); (b) the geological section through the Realmonte mine oriented E–W, and the well log which summarises all the rocks (mod. from CARG Sheet-636, Agrigento).

Muon radiography

Basic principles

Muon Radiography is based on the measurement of cosmic muons, elementary particles produced in the upper layer of the Earth’s atmosphere by the interaction of primary cosmic radiation, consisting mainly of protons, with the nuclei of the atmosphere. The energy spectrum of muons at sea level has been measured by various experiments. It is characterised by a continuous trend ranging from a few MeV up to TeV and beyond34,35.

Muons interact electromagnetically with the constituents of matter, electrons and nuclei. Interaction with nuclei mainly results in a deviation from the ideal rectilinear trajectory. For high-energy muons (greater than tens of GeV), this effect can be neglected and it will be assumed that they pass through matter in a straight line22. Interaction with electrons results in a continuous loss of some of their energy. The total loss when crossing a layer of rock is proportional to its length and mass density. The detection of cavities within a large object is based on the measurement of the attenuation of the cosmic muon flux due to the energy lost in the matter. To be more quantitative, consider a stretch of length in rock L with a mass density function \(\rho\). The opacity X is then defined as:

If the density is constant along L the equation becomes:

while, if this is not the case, the opacity can be written in terms of the average density \({\overline{\rho }}\) :

It is useful to express rock thickness in terms of water equivalent length (WEL), i.e. the amount of water thickness that produces the same energy loss in the rock. Since, at first order, the stopping power of matter is directly proportional to its density, a first approximation of the WEL value is obtained by simply multiplying the length of the rock by its mass.

In order for a muon to pass through a certain thickness of rock of opacity X, a certain minimum energy \(E_{min}(X)\) is required, which will depend on X. Since the cosmic muon spectrum is continuous, the underground flux will be attenuated compared to the surface flux. From the measurement of the attenuation and by using theoretical models, it is possible to determine X. The measurement of X can then be interpreted, depending on the assumed model, either as an indication of voids—if the apparent rock density is assumed constant—or as an estimate of average density, if the rock is assumed to be void-free.

Imaging of a cavity: the relative transmission

Following the approach of17,18, the presence of a density anomaly in a certain direction \(\hat{d}\) can be revealed by comparing the measured muon transmission versus the expected transmission. The measured transmission \(T_M({\hat{d}}\,)\) is a directional function, defined as the fraction of muons reaching the detector—placed at a specific underground location—compared to those measured at the surface during a free-sky acquisition. In a free-sky data acquisition, the detector is unobstructed or shielded only by obstacles of minimal and known thickness.

\(T_M({\hat{d}}\,)\) can be evaluated from the measured subsurface muon rate \(N_u(\hat{d};X)/\Delta T_{u}\) and the free-sky muon rate \(N_{fs}({\hat{d}}\,)/\Delta T_{fs}\) where \(\Delta T_{u}\) and \(\Delta T_{fs}\) are the acquisition times of the two measurement campaigns, respectively. Assuming that the muon detection efficiency is the same in the two measurement campaigns, the measured transmission \(T_M({\hat{d}}\,)\) is defined as:

where \(C_N\) is a normalisation constant that takes into account possible systematic differences in the free-sky and underground measurement, such as different data acquisition efficiency.

The expected transmission \(T_E({\hat{d}}\,)\) is the transmission evaluated with a numerical model under certain assumptions about the average density of the material passed through and the presence of voids. The number of muons measured by the detector in a certain acquisition time \(\Delta T\) can be expressed as:

where \(\epsilon ({\hat{d}}\,)\) is the detection efficiency,

\(S_{eff}({\hat{d}}\, )\) is the so-called effective area which depends on the detector surface and the geometrical efficiency, \(I(\hat{d},X )\) is the integrated flux with respect to the energy:

where \(\Phi (\theta ,E)\) is the differential muon flux on the surface of the Earth, which is assumed to depend only on the zenith angle \(\theta\) and the muon energy. \(E_{min}\) is the minimum muon energy required to reach the detector in a certain direction \(\hat{d}\), which corresponds to a certain opacity \(X({\hat{d}}\,)\). Assuming that underground and free-sky data acquisitions have the same efficiency, for the same acquisition time, we can write the expected transmission as

\(E_0\) is the minimum energy of the muon for the free-sky measurement, depending on the material of the detector and of any structure covering the detector, in our case we estimated \(E_0\sim 200\) MeV for our detector, taking into account the 6 layers of plastic scintillator (about 10 cm total), 6 mm of aluminum from the detector’s container, and 5 sheets of iron (10 mm total) used as a filter for soft cosmic radiation, placed above the intermediate plane. The contribution from the roof of the hut, made of lightweight sheet metal. We have verified that a difference on the order of 100 MeV in the value of \(E_0\) has an effect on the variation of the expected transmission of less than 1%.

From the expected and measured transmissions, it is possible to define the relative transmission \(RT({\hat{d}})\):

The expected value for RT is \(\sim 1\) in all directions in which the model correctly describes the real matter distribution. If, for example, a cavity is not described within the model, a value \(RT({\hat{n}} )> 1\) will be observed in the direction in which the cavity is seen by the detector because the number of measured muons will be greater due to the intercepted hollow.

In order to take in account the statistical fluctuations the normalised relative transmission RTN is introduced:

which expresses the deviation of RT from the expected value in terms of its statistical error.

Expected results

The numerical model

In order to carry out a feasibility study of the measurement in the mine, a simulation program was developed to produce synthetic data. First a digital model of the mine was produced, taking in account a digital terrain model (DTM) of the mine surface, all the known cavities in the acceptance of the detector and the mass density distribution. A simplified digital model of the detector was developed too, taking in account its geometry. In brief, the main steps for the production of a synthetic data sample are the following. For a certain position \(P_D\) of the detector inside the mine the program computes:

-

1.

The amount of rock a muon passes through to reach the detector, both in the absence of cavities and by subtracting the thicknesses of the intercepted voids

-

2.

The equivalent opacity, based on an expected mass density distribution

-

3.

The muon flux measured by the detector at the surface and at the position \(P_D\)

-

4.

The normalised relative transmission RTN for a certain acquisition time \(\Delta T\)

To calculate the distance between the surface muon entry point and the detector a DTM was used. The DTM was derived from LIDAR sensor ATA flight 2012-2013 Sicily Region36, expressed in the Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) system with a spatial resolution of 2 m in the WGS84 - UTM33N horizontal plane and 10 cm in the vertical direction. For the calculation of the crossed voids, the known tunnels were modeled with a simplified 3D geometry with a spatial resolution of approximately 1 m.

This DTM was then integrated, in order to increase its resolution, with a new terrain model, produced by means of both photogrammetric and Lidar surveys from a DJI Matrice 300 drone, through flight cycles at varying heights of between 30 m and 160 m. The drone surveys covered the entire orography above the tunnels between the entrance and the point of installation of the detector. Aluminum scale bars were positioned at the entrance, whose markers were surveyed by total station in order to link the DTM of the area with the tunnel models produced by laser scanner. The topographical survey was in fact hooked up to the local reference system in use by Italkali technicians, in Cassini-Soldner coordinates, by means of points determined from Land Registry maps referring to the lots adjacent to the mine and the topographical points arranged on the crown of the tunnels.

During the same acquisition campaign, surveys were carried out using a Riegl VZ400 time-of-flight laser scanner and a Zoller+Fröhlich 5016A phase-shift laser scanner, the latter in static and dynamic configuration using the FlexScan platform. The object of the survey was the collector at an elevation of -106 m, for a length between traverses VI and XVI, and the collector at an elevation of -85 m, for a length between traverses IX and XVI, as well as the descending slope that connects the inlet to the collectors.

The survey using Riegl produced 29 (\(-106; -85\)) + 136 (descending slope) scan positions with an average resolution of 7 mm at a distance of 10 m, the 69 ZF point clouds returned a model with a resolution of 6.3 mm at 10 m. During the acquisition phases with both instruments, series of cylindrical and flat markers were located, which were simultaneously surveyed by total station and referred to the topographic points located by Italkali technicians at crown height during the excavation phases. In this way, the models of the collectors and the two XVI traverses were referred to scale bars and topographic points outside the mine, previously surveyed, and therefore aligned with the DTM generated by drone.

The production of systems for the transfer of the WGS84 coordinate models is currently underway and will be carried out using ground control points acquired externally by total station and drone flights in RTK mode.

The results presented in the next section were obtained by considering a single mineral, alite, that is, sodium chloride with a density of about 2.2 g/\(\hbox {cm}^3\). The \(E_{min}\) was calculated numerically using for muon energy loss, the model and tables proposed in37 and using as material the so-called standard rock with average density 2.65 g/\(\hbox {cm}^3\) and average atomic number 11 and rescaling for different densities. The effect on energy loss with the actual composition of the rock will be evaluated in the future. In any case, as reported in38, no systematic effects greater than a few percent are expected. To calculate the muon rates the so-called modified Gaisser differential muon flux \(\Phi (\theta ,E)\)34,39 was used. This model has been used by various experiments with excellent agreement with the data, even better than other generators available in the literature40,41,42.

Expected results for the first test in the mine

As first test the detection of some galleries at -85 ASL level, called T1_m85 and G1_m85, was chosen. The detector is located at level -106 ASL in a position called T16_m106 that is below the crossing of two galleries T1_m85 and G1_m85. Figure 3 shows the galleries involved with the detector position (left), and the intersection of the void seen by the detector due to its geometric acceptance (rigth).

Left: plan of the tunnels involved in the test: in blue are the tunnels at the \(-106\) level where the detector location is shown, indicated with a black dot. In red are the tunnels at the \(-85\) level. Right: The green volume represents the void at the \(-85\) level intercepted by muons reaching the detector at the \(-106\) level (black dot).

The total amount of rock traversed by muons to reach the detector is between a minimum of about 190 m in the vertical direction \(\theta =0^\circ\) to a maximum of about 320 m at \(\theta =45^\circ\). Given the halite density \(\rho _A = 2.2 \times 10^3 \mathrm {kg/m^3}\) the equivalent WEL is between 380 and 704 m. The amount of void traversed by the muon is summarised in Table 1, where the void calculation was carried out in three different cases, considering both the contribution of the tunnels at -106 and -85 and expressed as a percentage of length and WEL relative to the rock thickness. The difficulty of the measurement is obvious because the variation in rock thickness due to the tunnels is on the order of a few percent and because the expected muon rate is very low, on the order of 0.1 Hz, as confirmed by the first measurements obtained at the underground site, which results in long acquisition times in order to accumulate the statistics necessary to contain the statistical fluctuations in the number of muons measured in each direction.

Ideal relative transmission, obtained without considering statistical variations in the number of muons measured. Left: contributions from the voids at \(-106\) and \(-85\). Middle: contribution due to the voids only at \(-106\). Right: contribution due to voids only at \(-85\). All histograms have a bin size of \(1^\circ \times 1^\circ\).

Example of applying a filter to reduce statistical fluctuations and improve cavity image quality. Left: no filter applied. Middle: application of a median filter \(3 \times 3\). Right: RTN bins in the middle figure with values \(<0\) are set to zero to improve image contrast. All histograms have a bin size of \(4^\circ \times 4^\circ\) and the same data acquisiton time of 60 days.

In Fig. 4 the ideal Relative transmission \(RT({\hat{d}}\,)\) is plotted as a function of the direction \({\hat{d}}\) expressed in polar coordinates:

where \(\theta\) is the zenith angle measured with respect to the vertical Z axis ( \(\theta = 0\) is the vertical direction), and \(\phi\) is the azimuth angle, measured counterclockwise from the X axis (with the positive X axis pointing toward geographical East).

The ideal relative transmission is obtained without considering the statistical fluctuations in the number of muons measured by the detector, with a data hold of unlimited duration. Three plots are shown in Fig. 4, in which the RT due to the sum of the voids at \(-106\) and \(-85\) and the two contributions considered individually are shown. This figure can be compared with Fig. 5, where the effect of the statistical contribution for a 60 days measurement campaign is shown. Given a certain sample of muons, the use of a larger histogram interval allows more muons per interval to be collected, thus reducing relative statistical fluctuations and increasing the statistical significance of normalised relative transmission RTN. As a downside, obviously a worsening of the angular resolution is obtained. In Figs. 6 and 7 it is possible to observe the effect on the RTN of the duration of the data acquisition and of the histogram bin size.

Dedicated filtering algorithms can be applied to the data sample to enhance the image quality of the voids. As an example in Fig. 8 a median filter is applied to a 60 days data taking simulation.

The muon detector

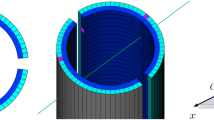

The muon detector in use for this project was built about 15 years ago and used for the last time in 201517,18. Numerous upgrades in the mechanics and in the electronics were carried out before it went into operation in the mine. The detector is composed of six detection units. Each detection unit has a sensitive plane, of approximately 1 m² area, that provides one Cartesian coordinates of the impact point of the muon with the detector. The plane is composed with two modules, each made of 32 plastic scintillator bars coupled with silicon photomultipliers photosensors (SiPMs). SIPMs signals are conditioned by a dedicated front-end electronics (FEE). All these elements are integrated into a single aluminum shell equipped with handles to facilitate handling and deployment on-site if the detector cannot be transported to the measuring site already assembled, but must be assembled on site. Cabling is minimised through the use of a few circular military-class connectors, while power distribution has been optimised: all required voltages, including the Silicon Photomultiplier (SiPM) bias, are generated directly on the front-end boards from a single 6 V input supply.

The fundamental sensitive elements of the detector are plastic scintillator bars with a triangular cross-section (3.3 cm base, 1.7 cm height, 107 cm length). Each bar is extruded with a 2 mm central hole through which a 1 mm wavelength-shifting optical fiber (BICRON BCF92) is inserted. A 0.25 mm TiO2 reflective coating enhances internal light yield and provides shielding from ambient light. When a muon crosses a scintillator bar, the resulting light signal is captured by the fiber and conveyed to a SiPM. The SiPMs, manufactured by Hamamatsu (MPPC S12825-050P), are mounted on a custom-designed PCB, with one SiPM optically coupled to each fiber via a dedicated connector. In summary, each detection unit includes a sensitive plane composed of 64 composed of 64 scintillator bars arranged in two half-planes of 32 bars each, where adjacent bars are alternately flipped.

The detection units are arranged in three pairs, each consisting of two planes whose scintillator bars are oriented orthogonally. This makes it possible to trace the x, y and z coordinates of the muon impact point with the planes. A line in space is then obtained from the three impact positions, which defines the direction of the muon. The three couples are positioned horizontally at a distance step of 25 cm. The spatial resolution of the detector planes is about 2 mm, which corresponds, for a distance between the first and last plane, to an angular resolution of about 4 mrad ( 0.2\(^\circ\)).

The FEE board is based on the EASIROC chip43, which manage SiPM biasing and analogic and digital shaping of the signal. As a muon traverses the detector, each impacted modules generates a fast digital signal. The data acquisition is triggered by a time coincidence among signals from at least 5 planes, specifically the four of the top and bottom planes and at least one of the planes belonging to the middle planes. The charge information corresponding to the energy deposited in each scintillator bar is digitised via ADCs and collected by the DAQ system, which records the data for offline muon track reconstruction.

For this project a new, upgraded acquisition system (DAQ) was used and a dedicated electronic interface, enabling the adaptation of the pre-existing front-end electronics to the latest, was developed. The entire system is fully remotely controllable via Internet-connected power management devices. Their combined use allows for selective power control of individual detector components, minimizing the risk of damage to the electronics in the event of sudden power cuts. Additionally, the use of an uninterruptible power supply (UPS) provides operators with sufficient time to intervene during outages and protects the system from potentially harmful voltage fluctuations that could affect data quality. The block diagram of the MURAY44 setup is shown in Fig. 9.

Block diagram of the data acquisition and remote control system for the detector. The MUNET computer manages data collection and storage on the NAS, powers the detector via a UPS, and controls smart plugs for remote management of power and ventilation. Internet connectivity enables remote monitoring and operation, and real-time data transfer.

As part of the detector upgrade, the mechanical structure was adapted to ensure integrity during transport and reliable operation in the challenging environment of a salt mine. To mitigate the risk of corrosion caused by airborne salt particles, an enclosure with protective and sealed walls, as well as connectors with hermetic plugs, has been implemented to protect the electronic components and other sensitive components. These modifications aimed to preserve long-term detector integrity and functionality while minimizing maintenance in a low-humidity saline-saturated atmosphere. The mechanical case was also designed to allow the detector to be tilted up to a maximum of 23\(^\circ\). To ensure stable detection performance, a compact air-conditioning unit was installed to maintain a controlled internal environment. Through dedicated air inlets, hermetically sealable, it continuously supplied air at 24 \(^{\circ }\)C, keeping the SiPMs at a constant and stable operating temperature. An image of the detector and deployment in the mine is shown in Fig. 10.

Installation in Realmonte, data quality and monitoring

Following the laboratory test phase, the detector was transported to the Realmonte mine and installed in a shed on the surface and acquired free-sky calibration sample for about two months. Three different data set have been acquired:

-

1.

detector with planes orientated horizontally and operative air conditioning for temperature regulation,

-

2.

detector with planes orientated horizontally without air conditioning,

-

3.

detector with planes tilted of about 23\(^\circ\) with respect to the horizontal plane.

The data acquisition is organised in sub-samples, called runs, of about 1 hour of duration. For each run, the following measurements are performed:

-

1.

Muon trigger rates,

-

2.

Accidental rates,

-

3.

Dark noise of the SiPM (OR32),

-

4.

Acquisition of electronic sample for ADC baseline and single-photoelectron response measurement,

-

5.

Acquisition of a sample of muons.

During data acquisition, temperature and humidity inside and outside the detector are measured, as well as the position and inclination of the detector, using a 9-axis accelerometer. The collected statistics are summarised in Table 2. During the two-month measurements, continuous online monitoring and automatic data processing ensured data quality with email alert if any parameter is not correct (power, accidental rates, muon trigger rate, internal and external temperatures and humidity, channel-by-channel count rates, electronics baseline and single-photoelectron values).

The muon sample is acquired according to a trigger logic, which consists of the condition that at least one time coincident signal is produced in each of the four upper and lower planes and at least one signal from one of the two middle planes. The tracking algorithm contains track point calculations based on energy-weighted and angle-corrected cluster (channel group) positions. The position of a cluster which contains only one channel is randomised uniformly around the channel center to avoid the pile up of events.

The first data allocation period will serve for later measurements as a reference to normalise angle-dependent efficiencies and check stability. The second period shows the temperature dependence. The muon trigger rates, track rates and inner temperature of the first two periods (horizontal detector with AC on and off) are shown in Fig. 11. The track rate refers to the number of tracks divided by the measurement duration, corrected for the DAQ dead time. Temperature correlations are clearly observed without AC, whereas AC-regulated rates demonstrate consistent stability.

First results and comparison with simulated data

After the reconstruction of tracks, described in the previous section, the free-sky muons are counted in angular bins. The count maps of the first (horizontal) and third (tilted) measurement periods are shown in Fig. 12.

It is necessary to ensure that the angular dependence of efficiencies are not changing in time (as stated at Eq. 5) since we later intent to use free-sky data to cancel out systematic detector effects. For this purpose, the ratio of Period 1 and Period 2 track counts for each angle bin is plotted in Fig. 13. As it can be seen from the figure, the ratio of different measurement periods deviates from 1 by less than a few percent, particularly in the geometric acceptance region of interest between \(-45^\circ\) and + 45\(^\circ\).

Data and synthetic data of free-sky muons are in good agreement, as it’s possible to observe in Fig. 14 where the angular dependence with respect to the zenith angle and \(d_x\) polar direction are shown. In Fig. 15 left, a preliminary measured transmission \(T_M({\hat{d}}\,)\) from the -106 level of the mine is shown. The plot was obtained using a sample of muons acquired in about 50 days of effective data taking and contains about \(2\times 10^5\) reconstructed tracks. In the same figure the expected ideal transmission \(T_E( {\hat{d}}\,)\) is shown. The two plots are in good qualitative agreement. As mentioned in “Expected results” a new survey of the mine has been performed. Once these data have been processed and using a sufficiently large muon sample, it will be possible to obtain the first tests on the images of the galleries present.

Left: Histogram of tracks directions as function of the zenith angle (integrating over azimuth angles) from period 1, compared to Monte Carlo simulation. Right: Histogram of tracks direction as a function of the \(d_x\) polar coordinate (obtained by projection of polar coordinates over \(d_y\) in Fig. 12 left). The shapes are normalised to their respective maximum values.

Left: measured transmission from the \(-106\) level, acquired in about 50 days of effective data acquisition with about \(2\times 10^5\) reconstructed tracks. Right: expected ideal transmission obtained from the same detector position of the \(-106\) level. Both histograms have 4\(^{\circ }\) \(\times\) 4\(^{\circ }\) angular bins.

Future measurements

The detector will acquire data at the current measuring point for an estimated time period of approximately 4 months. Further measurements, at different locations, are being evaluated in order to perform a 3D reconstruction of the tunnel. In addition to the cavity study, analyses of the geological structure of the mine are also planned, using a numerical model of the hillside that incorporates existing knowledge from surveys and sample collection.

Conclusions

Salt mines represent an interesting opportunity for storing green hydrogen, thanks to the chemical and physical properties of the mineral they are composed of. However, their characterisation using traditional geophysical methods is difficult and/or costly. Muon Radiography may represent a valid, alternative or complementary tool for studying cavities and, more generally, the mass density distribution above mine tunnels. The thickness of the rock and the density of the ore greatly reduce the measurable muon flux, so it is very relevant to be able to estimate the time required to detect a cavity and to be able to verify these estimates through field measurements. In this article, we have shown, through feasibility studies, that a few months of data taking could be sufficient to make an initial image of a gallery at the site of Realmonte, in Sicily, IT. A muon tracker of approximately 1 \(\hbox {m}^2\) of active surface area was installed at the complex and, after acquiring surface calibration data, was installed in a tunnel at \(-106\) m ASL, where the thickness of overhanging rock is of the order of 500 m WEL. This tunnel is located in correspondence with a similar tunnel at \(-85\) m ASL, which will be used as a test cavity. Analysis of the surface data shows that the detector is functioning correctly and measured data are in agreement with the synthetic data. Preliminary results from level \(-106\) show a good agreement between the measured transmission and the expected transmission. The first results are expected from the \(-106\) m measurement point after about four months of effective data collection, after which the detector will be moved to different positions in order to make 3D reconstructions of the tunnel and perform analyses of the density distribution of the mine.

Data availibility

The datasets analyses during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Conference on the Future of Europe. Report on the Final Outcome (Official Journal of the European Union, 2022).

Ravestein, P., van der Schrier, G., Haarsma, R., Scheele, R. & van den Broek, M. Vulnerability of European intermittent renewable energy supply to climate change and climate variability. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 97, 497–508 (2018).

Gas Infrastructure Europe. GIE storage map (2021).

Amro, M., Freese, C. & Häfner, F. Tightness of salt rocks using different gases for the purpose of underground storage. Oil Gas Eur. Mag. 2, 78–81 (2016).

Bunger, U. et al. Compendium of Hydrogen Energy (Elsevier, 2016).

Landinger, H. & Crotogino, F. The role of large-scale hydrogen storage for future renewable energy utilisation. In Second International Renewable Energy Storage Conference (IRES II) (2007).

Driad-Lebeau, L. et al. Geophysical Detection of Underground Cavities. In Proceedings of the Post-Mining Symposium (2008).

Jones, I. Seismic imaging in and around salt bodies. Interpretation 2 (2014).

Kosecki, A., Piwakowski, B. & Driad-Lebeau, L. High resolution seismic investigation in salt mining context. Acta Geophys. 58, 15 (2010).

Yaramanci, U. Geoelectric exploration and monitoring in rock salt for the safety assessment of underground waste disposal sites. J. Appl. Geophys. 44(2–3), 181–196 (2000).

George, E. P. Cosmic rays measure of overburden of tunnel. Commonwealth Eng. 455–457 (1955).

Alvarez, L. W. et al. Search for hidden chambers in the pyramids. Science 167, 832–839 (1970).

Bonomi, G., Checchia, P., D’Errico, M., Pagano, D. & Saracino, G. Applications of cosmic-ray muons. Prog. Particle Nucl. Phys. 112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2020.103768 (2020).

Bonechi, L., D’Alessandro, R. & Giammanco, A. Atmospheric muons as an imaging tool. Rev. Phys. 5, 100038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revip.2020.100038 (2020).

Oláh, L., Tanaka, H. K. M. & Varga, D. (eds.) Muography: Exploring Earth’s Subsurface with Elementary Particles. Geophysical Monograph Series (American Geophysical Union, 2022).

Scampoli, P. & Ariga, A. (eds.) Cosmic Ray Muography (World Scientific, 2023).

Saracino, G. et al. Imaging of underground cavities with cosmic-ray muons from observations at Mt. Echia (Naples). Sci. Rep. 7(1), 1181. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01277-3 (2017).

Cimmino, L. et al. 3D muography for the search of hidden cavities. Sci. Rep. 9, 2974. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39682-5 (2019).

Beni, T. et al. Transmission-based muography for ore bodies prospecting: A case study from a skarn complex in Italy. Nat. Resour. Res. 32, 1529–1547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11053-023-10201-8 (2023).

Borselli, D. et al. Three-dimensional muon imaging of cavities inside the Temperino mine (Italy). Sci. Rep. 12, 22329. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-26393-7 (2022).

Schouten, D. Muon geotomography: Selected case studies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 377(2137), 20180061. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2018.0061 (2018).

Lechmann, A. et al. Muon tomography in geoscientific research—A guide to best practice. Earth-Sci. Rev. 222, 103842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103842 (2021).

Joutsenvaara, J. et al. The Horizon Europe AGEMERA project: Innovative non-invasive geophysical methodologies for mineral exploration. Adv. Geosci. 65, 171–180. https://doi.org/10.5194/adgeo-65-171-2025 (2025).

Balázs, L. et al. 3-D muographic inversion in the exploration of cavities and low-density fractured zones. Geophys. J. Int. 236, 700–710. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggad428 (2023).

Roveri, M., Lugli, S. & Manzi, V. The desiccation and catastrophic refilling of the Mediterranean: 50 years of facts, hypotheses, and myths around the Messinian salinity crisis. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 17. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-021723-110155 (2024).

Lugli, S., Manzi, V., Roveri, M. & Schreiber, B. The primary lower gypsum in the Mediterranean. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 297, 83–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.07.017 (2010).

Lugli, S., Schreiber, B. & Triberti, B. Giant polygons in the Realmonte mine. J. Sediment. Res. 69, 764–771. https://doi.org/10.2110/jsr.69.764 (1999).

Decima, A. Initial data on bromine distribution in the Miocene salt formation of southern Sicily. Mem. Soc. Geol. Ital. 16 (1978).

Roveri, M. et al. Clastic vs. primary precipitated evaporites in the Messinian Sicilian basins. Acta Nat. 42, 125–199 (2006).

Speranza, G., Cosentino, D., Tecce, F. & Faccenna, C. Paleoclimate reconstruction during the Messinian evaporative drawdown. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 14(12), 5054–5077. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013GC004946 (2013).

Yoshimura, T. et al. An X-ray spectroscopic perspective on Messinian evaporite from Sicily. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 17(4), 1383–1400. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GC006233 (2016).

Decima, A. & Wezel, F. Late Miocene evaporites of the Central Sicilian Basin. DSDP Proc. https://doi.org/10.2973/dsdp.proc.13.144-1.1973 (1973).

Butler, R., Maniscalco, R., Sturiale, G. & Grasso, M. Stratigraphic variations control deformation patterns in evaporite basins. J. Geol. Soc. 172(1), 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2014-024 (2014).

Gaisser, T. Cosmic Rays and Particle Physics (Cambridge University Press, 1990).

Gaisser, T. K. & Stanev, T. Cosmic rays (review of particle physics). Phys. Lett. B 592, 228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2004.06.011 (2004).

Digital Terrain Model Sicily.

Groom, D., Mokhov, N. & Striganov, S. Muon stopping-power and range tables, 10 MeV-100 TeV. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 78, 183–356 (2001).

Lechmann, A. The effect of rock composition on muon tomography measurements. Solid Earth 9, 1517–1533. https://doi.org/10.5194/se-9-1517-2018 (2018).

Guan, M. A parametrization of the cosmic-ray muon flux at sea-level. arXiv: 1509.06176.

Procureur, S. et al. Precise characterization of a corridor-shaped structure in Khufu’s pyramid by observation of cosmic-ray muons. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36351-0 (2023).

Oláh, L. et al. Investigation of the limits of high-definition muography for observation of Mt Sakurajima. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2018.0135 (2019).

Han, R. et al. Cosmic muon flux measurement and tunnel overburden structure imaging. JINST https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/15/06/P06019 (2020).

Callier, S. et al. EASIROC, an easy and versatile readout device for SIPM. Phys. Proc. 37, 1569–1576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phpro.2012.02.486 (2012).

Anastasio, A. et al. The MU-RAY detector for muon radiography of volcanoes. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 732, 423–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2013.05.159 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the Italkali company and all the staff of the Realmonte mine. In particular, we would like to thank the mine director, Ing. Cristian Sabatino, and Messrs Gino De Rosa and Francesco Palumbo, who supervised and assisted with the installation of the detector. We would also like to greet with affection Prof. Paolo Strolin, who first introduced us to the study of Muon Radiography. This project was partly financed by the Italian Ministry of University (MUR) through the PRIN-PNRR 2022 call for proposals, project identification code P2022EBPMH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: F.A., G.S., D.I. Methodology: F.A., G.N., G.S. Geological and survey data: G.A., D.D.M., D.I., M.A.L., L.R. Muon radiography data reconstruction and analysis: G.N., G.S. Detector upgrade: C.A., V.B., L.C., I.D., M.M., V.M., G.N., G.S. Detector installation: V.B., L.C., D.I., G.N., G.S. Data acquisition and front end electronics: A.A., V.B., L.C., V.M., M.M., G.S. Slow control and remote control: V.B., L.C., G.N. Writing original draft: G.N., G.S. Review of the draft paper: all the authors. Project supervision: G.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saracino, G., Nyitrai, G., Ambrosino, F. et al. Detection of cavities in a salt mine with cosmic muons: expected results and first data. Sci Rep 15, 34147 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11685-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11685-5