Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) have been proven to have a crucial role in intercellular communication and have attracted significant attention in the physiology of reproduction because of their multiple functions in physiological processes essential for reproduction including gametogenesis, fertilization and embryo-endometrial cross-talk. Although EVs from the male reproductive tract have been extensively studied for their role in sperm maturation, research on female reproductive tract-derived EVs in humans is still emerging and supported by only a few studies to date. In vitro study was performed using spermatozoa from normozoospermic men and EVs isolated from follicular fluid (FF-EVs), cervicovaginal fluid collected 2 and 7 days after the LH surge (CVF-EVs LH + 2 and LH + 7, respectively) and spent medium of decidualized (dESCs-EVs) and non-decidualized (eESCs-EVs) endometrial stromal cells from healthy women of reproductive age. The principal outcome measures comprise the percentage of viable, progressively motile, and capacitated spermatozoa after treatment with FF-EVs, CVF-EVs LH + 2 and LH + 7, dESCs-EVs, and eESCs-EVs. Spermatozoa are able to capture EVs derived from all the considered tracts of the female reproductive system, with slightly varying efficiencies, albeit comparable in most cases. Incubating sperm cells with any of these EVs does not have any detrimental effect on sperm vitality, increases the percentage of spermatozoa displaying progressive motility and the percentage of acrosome-reacted spermatozoa. EVs produced and released in various regions of the female reproductive system likely contribute to spermatozoa maturation during their transit, promoting both capacitation and motility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) play a pivotal role in intercellular communication by transporting molecular cargoes between donor and recipient cells throughout the body. Their involvement in reproductive processes has garnered significant attention, with studies highlighting their presence in both female and male reproductive systems1,2,3,4.

In females, EVs contribute to crucial reproductive events, including gamete maturation, fertilization, embryo development, and implantation, while in males, they are integral to spermatozoa maturation and function. Indeed, our previous work has shown that EVs isolated from the seminal plasma of normozoospermic men enhance sperm motility and induce capacitation, underscoring their significance in male fertility5.

In recent years, research has deepened our understanding of EVs’ role in female reproductive biology, particularly in the follicular and oviductal environments. For instance, follicular EVs have been shown to enhance meiotic resumption in domestic cat vitrified oocytes6, support cumulus expansion in bovine follicular cells7, and regulate granulosa cell proliferation8. Beyond the follicular context, EVs from bovine oviductal fluid have been found to positively impact in vitro embryo development and quality, further suggesting their supportive role in early embryogenesis9. Interestingly, studies conducted mainly in animal models, demonstrated that EVs produced in the female reproductive tract also play a crucial role in modulating sperm function. EVs from oviductal fluid, uterine fluid, and follicular fluid have been implicated in inducing sperm capacitation and enhancing sperm motility and fertilization capacity. For instance, in domestic cats, oviduct-derived EVs improved sperm motility and fertilizing ability10, while bovine oviduct-derived EVs stimulated the acrosome reaction and capacitation in spermatozoa, as evidenced by increased protein tyrosine phosphorylation11. Recent studies on human beings revealed that FF-EVs contain proteins involved in sperm activation and progesterone, the latter higher in young women12, while EVs were isolated from the uterine flushing fluid promote acrosome reaction13. Moreover, the employment of mouse models has shed light on the involvement of uterine-derived EVs in mediating the transfer of crucial molecules such as the GPI-linked sperm adhesion molecule 1 (SPAM1) and the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase 4a (PMCA4a) to spermatozoa14,15,16. SPAM1 facilitates the penetration of spermatozoa through the zona pellucida by dispersing the cumulus oophorus complex17, while PMCA enzymes maintain calcium homeostasis in sperm cells, crucial for motility and fertilization. Deficiencies in PMCA have been associated with male infertility due to impaired sperm motility18.

Furthermore, follicular fluid-derived EVs have been implicated in spermatozoa maturation, maintaining sperm viability and inducing capacitation in bovine studies, thus actively contributing to the early stages of fertilization19.

This collective evidence highlights the multifaceted role of EVs in orchestrating various aspects of reproductive physiology, primarily spermatozoa maturation.

Most data have been obtained in animal models, with modest translation to human processes. We have previously demonstrated that sperm cells are able to capture EVs from human endometrial stromal cells (ESCs) and internalize through lipid raft-mediated endocytosis20. These vesicles were observed to increase phosphorylated tyrosine levels in sperm cells, indicating capacitation and stimulating the acrosome reaction.

In this study, we investigate the role of EVs derived from various tracts of the human female reproductive system in the initial stages of the fertilization process, with particular emphasis on assessing their impact on spermatozoa motility and capacitation. We isolated and tested EVs derived from follicular fluid (FF-EVs), cervicovaginal fluid collected during ovulation (CVF-EVs LH + 2), cervicovaginal fluid collected during the window of implantation (WOI) (CVF-EVs LH + 7), and from the spent medium of endometrial stromal cells decidualized to mimic the secretory phase of the cycle (dESCs-EVs) or treated with E2 to mimic the proliferative phase (eESCs-EVs).

Methods

Patients’ Enrollment and Sample Collection

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee (BC-GINEOS, approval date: 09/02/2012, San Raffaele Hospital Ethics Committee), and all participants provided written informed consent. Cervicovaginal fluid (CVF) samples (n = 20) were collected 2 and 7 days after the LH peak from women undergoing various assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatments. Specifically, LH + 2 samples were collected during intrauterine insemination, coinciding with ovulation, while LH + 7 samples were obtained during embryo transfer in In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) or Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI) cycles, corresponding to the WOI. Follicular fluid (FF) samples (n = 8) were obtained as byproducts during oocyte retrieval in IVF or ICSI cycles. Endometrial stromal cells (ESCs, n = 8) were isolated from endometrial biopsies collected from women undergoing laparoscopy for benign ovarian pathology, following the protocol by Viganò et al.21. Semen samples were collected from normozoospermic men after 2–7 days of abstinence and allowed to liquefy at 37 °C for 30 min before sperm isolation, which varied depending on the assay performed. All procedures adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki principles.

Sample processing and EV isolation

Cervicovaginal Fluid (CVF) Collection and EV Isolation

Two swabs were used to collect CVF from the vaginal fornix and immediately immersed in 4 mL of sterile saline solution in 50 mL Falcon tubes. Samples were processed immediately. After vortexing for 2 min to release biological material from the swabs, samples were centrifuged sequentially at 500 × g for 10 min and 2,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C to remove cells and debris. The resulting supernatants were transferred into 1.5 mL polypropylene microfuge tubes and ultracentrifuged at 110,000 × g for 2 h at 4 °C using a TLA 55 rotor in an Optima TLX ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter Inc.). EV pellets were resuspended in 100 µL of PBS filtered three times through a 0.10 μm membrane. Protein concentration was measured using the DC™ Protein Assay Kit (BioRad), and aliquots were stored at − 80 °C.

Follicular Fluid (FF) Collection and EV Isolation

FF samples were collected during oocyte pickup via transvaginal ultrasound-guided follicle aspiration in IVF or ICSI cycles. After removal of the oocyte-cumulus complexes, the remaining follicular fluid was centrifuged sequentially at 1,200 × g for 15 min, 1,000 × g for 15 min, 2,000 × g for 15 min, and 3,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C to remove cellular debris and apoptotic bodies22. 10 mL of FF supernatant were transferred into 38.5 mL open-top thinwall polypropylene tubes, and diluted with 0.1 μm triple-filtered PBS. Samples were ultracentrifuged at 110,000 × g for 90 min at 4 °C using an SW32Ti rotor in an Optima L-90 K ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter Inc.). EV pellets were resuspended in 100–300 µL of 0.1 μm triple-filtered PBS. Protein concentration was determined with the DC™ Protein Assay Kit (BioRad), and samples were aliquoted and stored at − 80 °C until further use.

Endometrial Stromal Cell (ESC) Isolation, Hormonal Treatment, and EV Isolation

ESCs isolated from endometrial tissue were hormone-treated for 4 days in DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 4% EV-depleted charcoal-stripped FBS to mimic the proliferative (eESCs, treated with 10 nM estradiol) and secretory (dESCs, treated with 10 nM estradiol, 1 µM progesterone, and 0.5 nM cAMP) phases of the menstrual cycle. Treatments were performed at 0 and 48 h, and conditioned media collected at 48 and 96 h and pooled. EV isolation from conditioned media was performed following the protocol previously published by Murdica et al. 202020. Briefly, conditioned media were centrifuged sequentially at 300 × g, 2,000 × g, and 10,000 × g at 4 °C to remove cells and debris. The resulting supernatants (~ 15 mL) were diluted with 0.1 μm triple-filtered PBS and ultracentrifuged at 100,000 × g for 70 min at 4 °C using an SW32Ti rotor in an Optima L-90 K ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter Inc.). EV pellets were resuspended in 100–150 µL of filtered PBS. Protein concentration was measured using the DC™ Protein Assay Kit (BioRad), and aliquots were stored at − 80 °C until use.

Nanoparticle tracking analysis

Particle size distribution and concentration of EVs were determined by Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) using a NanoSight LM10-HS instrument (NanoSight Ltd., Amesbury, UK) as previously described5. In details, to specifically fit the optimal working range of the instrument (20–120 particles per frame), FF-EVs samples (n = 2), CVF-EVs LH + 2 samples (n = 3) and CVF-EVs LH + 7 samples (n = 3) were diluted 1:300 with PBS filtered three times with a 0.10 μm filter, while dESCs-EVs (n = 3) and eESCs-EVs (n = 3) samples were diluted 1:100. Five videos, 30 s each, were recorded under the flow mode with camera level set at 13 and detection threshold set at 10. At least 200 completed tracks per video were collected. Videos were processed and analyzed using NTA software 2.3 (NanoSight Ltd., Amesbury, UK).

Transmission electron microscopy

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) analysis was performed to visually confirm EVs shape and abundance. Briefly, to perform the analysis, freshly purified EVs were absorbed on glow discharged carboncoated Formvar/Carbon copper grids and washed with water. Samples were contrasted with 2% uranyl acetate and air-dried. Zeiss LEO 512 transmission electron microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) was used for grids observation. Images were acquired by a 2 K × 2 K bottom-mounted slow-scan Proscan camera controlled by Esivisionpro 3.2 software.

Western Blot analysis

For soluble proteins detection, 20 µg of isolated EVs were lysed directly in reducing sample buffer, while for CD9 and CD63 detection, 10 µg of isolated EVs were lysed in non-reducing sample buffer. To be used as controls, eESCs and dESCs were lysed in lysis buffer [1% Triton X-100 (w/v), 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. P8340)] on ice for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 16,000 x g for 10 min at 4 °C to retrieve proteins. Subsequently, 20 µg of proteins were processed in reducing sample buffer and 10 µg of proteins were processed in non-reducing sample buffer. All samples were boiled at 97 °C for 10 min.

Proteins were resolved by means of a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electrotransferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Non-specific sites were blocked incubating membranes in 5% (w/v) non-fat powder milk in PBS-0.1% Tween. Membranes were incubated with the following antibodies: anti-CD9 (1:500, BD Pharmingen, #555370) O/N at 4 °C, anti-CD63 (1:5,000, BD Pharmingen, #556019) 1 h at RT, anti-Alix (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, #sc-271975) O/N at 4 °C, anti-TSG101 (1:1,000, NovusBio, #NB200-112) 1 h at RT, anti-CNX (1:1,000, Abcam, #ab75801) for 1 h at RT. After washings, membranes were incubated for 1 h at RT with secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies as follows: anti-mouse (BioRad, #1706516) 1:2,000 for Alix and CD9 membranes, 1:3,000 for TSG101 membrane and 1:15,000 for CD63; anti-rabbit (Cell Signaling Technology, #7074S) 1:2,000 for CNX membrane. Protein signals were detected using the enhanced chemiluminescence method (Immobilon® Western, Millipore, #WBKLS0500).

Biggers-Whitten-Whittingham (BWW) media

In all assays conducted in this study, spermatozoa were incubated in Biggers-Whitten-Whittingham (BWW) medium in its basal or capacitating versions. The capacitating BWW medium is composed of NaCl 95 mM, KCl 4,8 mM, CaCl 21,7 mM, MgSO4 1,2 mM, KH2PO4 1,2 mM, sodium lactate 20 mM, glucose 5 mM, sodium pyruvate 0,25 mM, NaHCO3 25 mM, supplemented with HEPES pH 7,2–7,4 10 mM, 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Lonza, catalog no. DE17602E) and human serum albumin (HSA) 3 mg/mL (CooperSurgical Inc.). The basal BWW medium is composed as described above, but, differently from the capacitating one, it contains NaCl 120 mM, CaCl2 0,2 mM and it is not supplemented with NaHCO3 and HSA. Both media were adjusted to pH 7,420.

EVs uptake evaluation

Isolated EVs were labelled with the green Vybrant™ DiO cell-labelling solution (Invitrogen, catalog no. V22886), following Invitrogen protocol. Briefly, 1 µL of dye was added for every 100 µL of EVs solution and incubation was performed for 30 min at 37 °C with agitation at 700 rpm. Then, Vivaspin® 500 centrifugal concentrators (Sigma-Aldrich, #VS0141) were used to remove the excess of unincorporated dye and to concentrate labeled EVs. To isolate only viable and motile sperm cells, Semen was loaded on Percoll™ (Cytiva, #17089101) gradient 85%/45% and centrifuged at 1,500 x g for 24 min at 20 °C. Pelleted sperm cells were washed with PBS and centrifuged at 600 x g for 5 min. Lastly, upon resuspension in basal BWW (5) medium, 1.5 × 106/well sperm cells were plated in low attachment Repro Plates (Kitazato, #83017) and EVs were added at a concentration of 50 µg/mL in a final volume of 200 µL/well. As negative control, spermatozoa were incubated with PBS filtered three times with a 0.10 μm filter, previously incubated with Vybrant™ DiO and loaded on Vivaspin® 500 columns, as for the EVs samples. Incubation was performed at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 4 h. After incubation, spermatozoa were washed twice with PBS to eliminate unbound EVs and then resuspended in PBS. EVs uptake was evaluated by means of flow cytometry: labeled sperm cells resuspension was analyzed with Accuri C6 Plus (BD Bioscience); 20,000 events, gated on spermatozoa population, were acquired for each sample. Data were recorded with the use of BD Facsdiva (Becton Dickinson) software and analyzed with FCS Express 7 (DeNovo) software.

Sperm progressive motility and vitality assay

Spermatozoa were isolated from the semen of normozoospermic men by centrifugation at 600 x g for 5 min at 25 °C, washed once with PBS and resuspended in capacitating BWW medium. Then, 750,000/well sperm cells were plated in Repro Plates (Kitazato) and supplemented either with 50 µg/mL EVs in a final volume of 100 µL/well or with HSA (3 mg/mL, CooperSurgical Inc., catalog no. ART-3001-5) in the positive control condition; untreated sperm cells served as negative control. Motility and vitality were evaluated after 1 and 4 h of incubation performed at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. For motility evaluation, at every time point, a 10 µL aliquot from each incubation condition was spotted on pre-warmed 90° frosted microscope slides (Epredia™, catalog no. AG00000112E01MNZ10). Motility was then evaluated at 40X magnification, following WHO guidelines23, differentiating spermatozoa in progressive, non-progressive and immotile. Vitality was evaluated through eosin staining. In both assays, at least 200 sperm cells/sample were counted.

Calcium ionophore-induced acrosome reaction (AR)

Spermatozoa were isolated, plated and incubated either with EVs or with HSA as described in the EVs uptake assay. The same positive and negative controls as the motility and vitality assay were included. After 1 and 4 h of spermatozoa incubation with EVs, the AR was pharmacologically induced incubating sperm cells with Ca2+ ionophore A23187 (8 µM, Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. C7522) for 30 min. Then, spermatozoa were washed twice with PBS and spotted in single drops on microscope slides. Drops were air-dried and then fixed with 4% PFA for 30 min in humid chamber. After washings with PBS, spermatozoa were stained with Coomassie blue G staining solution [0.22% (w/v) Coomassie blue G (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. B0770) in 50% methanol, 40% H2O, 10% acetic acid] for 5 min. After washing with water, coverslips were mounted using 1:1 PBS-glycerol solution and images were taken at 100X magnification with an Axio Imager M2 microscope (Carl Zeiss). At least 200 sperm cells/sample were counted differentiating acrosome reacted (white acrosome region) and acrosome intact (blue acrosome region) spermatozoa.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed with at least three independent biological replicates. Depending on the assay, Mann-Whitney U test or one-way ANOVA test followed by Bonferroni multiple comparisons test were performed to determine statistical significance. ns: p > 0.05, *: p ≤ 0.05, **: p ≤ 0.01, ***: p ≤ 0.001.

Results

Isolation and characterization of CVF-EVs, FF-EVs and ESCs-EVs

With the aim to investigate the role of EVs derived from various tracts of the human female reproductive system in the initial stages of the fertilization process, as depicted in Fig. 1, EVs were isolated from CVFs, FFs and ESCs spent media using ad hoc differential centrifugation protocols and characterized according to MISEV2023 guidelines24.

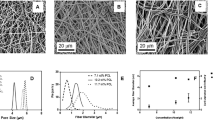

TEM images confirmed the presence of round-shaped EV-like particles in all samples, exhibiting diameters primarily ranging from 100 to 200 nm (Fig. 2a-f). In agreement with what was observed with TEM analysis, NTA revealed that, in all samples, EVs mean diameter spanned from about 140 nm to about 170 nm, thus consistently maintaining a mean size below 200 nm (Fig. 2g). This indicates that the isolated vesicle populations were enriched in small EVs25. Moreover, no statistically significant differences were detected among different EVs samples or in samples collected during different phases of the menstrual cycle.

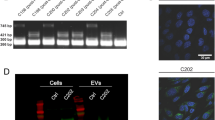

EVs characterization. (a-f) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) representative images of FF-EVs (a, b), CVF-EVs LH + 2 (c), CVF-EVs LH + 7 (d), dESCs-EVs (e) and eESCs-EVs (f). Scale bar: 500 nm. (g) Descriptive table reporting the average particle concentration, size and 90th percentile of the size (D90) obtained with NTA conducted on CVF-EVs LH + 2 (n = 3), CVF-EVs LH + 7 (n = 3), eESCs-EVs (n = 3), dESCs-EVs (n = 3) and FF-EVs (n = 2). (h) Western blot showing the presence of different canonical EV markers (Alix, TSG101, CD63, CD9) in representative samples of FF-EVs (n = 2), CVF-EVs LH + 2 and LH + 7 (n = 2) and of dESCs-EVs and eESCs-EVs (n = 1). Representative cell lysates from eESCs and dESCs (n = 1) were included as positive controls for CNX expression, used as EV negative marker.

The vesicular nature of isolated particles was confirmed by Western Blot analysis (Fig. 2h). All isolated EVs were positive for the canonical EV markers: tetraspanins CD63 and CD9, and the soluble proteins ALIX and TSG10126. CD9 was not detectable in endometrial stromal cells (eESCs and dESCs) but was clearly visible in their derived EVs, indicating an enrichment of this marker in the vesicles compared to the cells. EV purity was confirmed by the absence of the EV-negative marker calnexin (CNX), which was detected only in endometrial tissue samples (ESCs) used as positive controls. EVs isolated from follicular fluid (FF-EVs) showed low or no reactivity with some antibodies, including CD9. These results indicate variability in protein expression profiles among EVs depending on their cellular origin and source.

Sperm cells can capture EVs derived from different tracts of the female reproductive system

After isolating EVs from various female reproductive tracts, we aimed to investigate whether spermatozoa could capture these EVs after ejaculation.

We labeled FF-EVs, CVF-EVs LH + 2 and CVF-EVs LH + 7 with the fluorescein-based lipophilic dye Vybrant DiO, as spermatozoa’s ability to capture ESCs-EVs as previously demonstrated20. Spermatozoa derived from normozoospermic men were incubated with fluorescently labeled EVs for 4 h. Following incubation, the efficiency of spermatozoa in capturing EVs, indicated by the percentage of sperm cells exhibiting green fluorescence, was assessed using flow cytometry (Fig. 3a-d). FF-EVs resulted to be incorporated by 2.6 ± 0.6% (mean ± SE) of sperm cells, while CVF-EVs LH + 2 were captured by 1.4 ± 0.2% of spermatozoa, and CVF-EVs LH + 7 were incorporated by 4.4 ± 0.7% of sperm cells (Fig. 3e). Overall, these data confirm that spermatozoa can capture EVs originated from different tracts of the female reproductive system.

Human FF-EVs and CVF-EVs can be captured by sperm cells. (a-d) Representative flow cytometry dot plots. (e) Cumulative scatter plot (mean and SE) summarizing data from 3 (CVF) or 4 (FF) independent replicates; on the y axes, the percentage of green fluorescent sperm cells corresponds to the portion of spermatozoa that incorporated green-labeled EVs.

EVs from the female reproductive system do not alter sperm vitality

We then evaluated the potential impact of these EVs on various spermatozoa features. Initially, we assessed sperm vitality after 1 and 4 h incubation with each EVs group. Untreated (UT) spermatozoa incubated in simple basal BWW medium served as negative control, while spermatozoa incubated in capacitating BWW medium supplemented with human serum albumin (HSA) were used as a positive control, as this supplementation is commonly used to promote sperm survival in ART procedures27. The supplementation with FF-EVs, CVF-EVs LH + 2 or LH + 7, eESCs-EVs or dESCs-EVs did not elicit a statistically significant change in the percentage of viable spermatozoa when compared to the UT condition (Fig. 4). These results strongly indicate that all isolated EVs do not exert any significant detrimental effect on sperm vitality, providing the basis for proceeding with functional assays.

EVs from the female reproductive system support progressive sperm motility

To explore the functional effects of EVs on sperm cells, we investigated the impact of female reproductive system-derived EVs on spermatozoa motility. We assessed progressive motility, which is known to positively correlate with ART outcomes and pregnancy28, after 1 and 4 h of spermatozoa incubation with isolated EVs.

Spermatozoa incubated with HSA-supplemented capacitating BWW medium were evaluated as a positive control for increased motility, while UT spermatozoa as a negative control.

The exposure of spermatozoa to EVs resulted in a statistically significant increase in the percentage of progressively motile spermatozoa compared to the negative control (UT condition), indicating that the examined EVs positively affect sperm progressive motility (Fig. 5). With extended incubation periods, this percentage further increased together with the statistical significance.

Human FF-EVs, CVF-EVs and ESCs-EVs induce an increase in the percentage of progressively motile spermatozoa. The scatter plots summarize data (mean and SE) obtained from all independent replicates (n = 3) and show the percentage of progressively motile sperm cells after 1 (a) and 4 (b) hours of incubation with indicated EVs.

Collectively, at both time points, the enhancement in the percentage of progressively motile spermatozoa was comparable to that obtained in the positive control (+ HSA condition) and consistent across all EVs samples, with no single EVs group displaying a significantly better performance compared to the others. Indeed, starting from an average progressive motility of 37.2% ± 4.1% at t0, assessed prior to exposing spermatozoa to EVs treatment, the mean percentages of progressively motile spermatozoa after 1 h of incubation increased, ranging from 43.27 ± 4.9% in the + CVF EVs LH + 7 condition to 49.9 ± 3.8% in the + eESCs EVs condition. After 4 h of incubation, these percentages further increased, ranging from 45.37 ± 3.8% in the + CVF EVs LH + 7 condition, to 52.73 ± 2.7% in the + dESCs EVs condition.

EVs from the female reproductive system promote spermatozoa capacitation

Following the observation that EVs from different segments of the female reproductive system exert a functional influence/role on spermatozoa, specifically increasing the percentage of sperm cells exhibiting progressive motility, we explored whether these vesicles could play a role also in sperm capacitation. We evaluated this EVs feature in an indirect way that is by assessing the percentage of spermatozoa that, following 1 (Fig. 6a, b and c) and 4 (Fig. 6d, e and f) hours incubation with BWW supplemented wither with EVs or with HSA, undergo AR when pharmacologically triggered with a calcium ionophore. Following AR induction, spermatozoa were stained with Coomassie blue to distinguish acrosome reacted spermatozoa, displaying unstained acrosome region, from acrosome-intact sperm with blue-stained acrosome region.

Human FF-EVs (a and d), CVF-EVs (b and e) and ESCs-EVs (c and f) enhance/facilitate the completion of the induced acrosome reaction. The scatter plots summarize data (mean and SE) obtained from 3 or 4 independent replicates and show the percentage of acrosome reacted sperm cells after 1 (a, b and c) and 4 (d, e and f) hours of incubation with EVs.

The most significant increase in the percentage of acrosome-reacted spermatozoa was observed after 4 h of incubation, in line with the time-dependent nature of the capacitation process (Fig. 6). At this time point, spermatozoa incubated with all tested EVs showed levels of acrosome reaction comparable to those observed with the capacitating BWW + HSA condition, suggesting that EVs may contribute to promote capacitation. Specifically, after 4 h, 23.33 ± 2.81% of spermatozoa reacted upon incubation with FF-EVs (Fig. 6d), 22.63 ± 1.27% with CVF-EVs LH + 2 (Fig. 6e), 30.03 ± 4.20% with CVF-EVs LH + 7 (Fig. 6e), 25.2 ± 5.54% with eESCs-EVs (Fig. 6f), and 26.9 ± 3.01% with dESCs-EVs (Fig. 6f). A moderate increase in acrosome-reacted spermatozoa was also observed after 1 h of incubation, although to a lesser extent than that at 4 h, consistent with the progressive nature of the capacitation process.

Discussion

Many studies have been conducted to better understand EVs role in reproduction, but the vast majority of them have been performed on animal models, leaving this field relatively unexplored in humans. With the present study, we aimed to investigate whether EVs contribute to reproduction also in humans, focusing on their potential ability to promote sperm capacitation and increase sperm progressive motility, key processes towards fertilization.

To this aim, we isolated EVs from FFs, CVFs and spent medium of ESCs through differential centrifugations, in accordance to the updated guidelines of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV2023), to conjugate an adequate recovery yield with specificity24. Isolated EVs exhibited an average diameter below 200 nm, which is widely recognized as one of the standard reference size thresholds for distinguishing small EVs from medium/large ones25. Moreover, in the case of CVF-EVs and ESCs-EVs, the average size of the isolated EVs remained consistent across the two phases of the menstrual cycle analyzed. Similarly, also the mean particle concentration showed no significant differences among all the considered sources of EVs or when comparing different menstrual cycle phases within the same source. All the isolated EVs shared a comparable morphology and positivity for canonical EVs markers ALIX, TSG101, CD63 and CD9, thus confirming their vesicular nature.

Then, we demonstrated that spermatozoa can capture all isolated EVs with efficiency ranking from approximately 2% to about 4.5%. The incorporation efficiency of ESCs-EVs in the secretory or proliferative phase by spermatozoa had previously been investigated with comparable results20. In our experimental settings, EVs derived from CVF at LH + 7 showed higher uptake efficiency with respect to CVF-EVs LH + 2.

These percentages may appear modest, but it is to underline that spermatozoa constitute a highly heterogeneous population, in which sperm cells could exhibit different receptivity to EVs. Furthermore, it is crucial to emphasize that only one spermatozoa among the tens of millions present in the semen and enter the female reproductive tract during sexual intercourses that reaches the egg is sufficient for fertilization to occur.

Moreover, we have formerly demonstrated that the efficiency of spermatozoa in incorporating EVs is influenced by the pH, with increased uptake efficiency observed when sperm cells are exposed to a moderately acidic pH of 5.55. In the current study, spermatozoa were incubated with EVs in a medium adjusted to a pH of 7.4, which closely resembles the physiological conditions found in the uterus (~ pH 7.7) and in the fallopian tubes (~ pH 7.9), but not that of the cervicovaginal area in which pH falls within the range of 3.8 to 5.029. Consequently, it is likely that, in a physiological context, CVF-EVs might be incorporated with a higher efficiency as the pH in the upper vagina tends to be more acidic.

Notably, it has to consider that EVs can impact on sperm cells not only by being captured and transferring active cargoes, but other mechanisms can be considered as well, including a “kiss and run”, which involves direct interactions between proteins located on the EVs’ membrane and targets on the cell membrane30. This might explain why CVF-EVs LH + 7, collected during the WOI —the period in which the endometrium becomes receptive to embryo implantation— were more efficiently captured by spermatozoa compared to CVF-EVs LH + 2, which are produced around the time of ovulation. At this stage a fertilized egg is entering the uterus for implantation, or the oocyte has been discarded if not fertilized. In both scenarios, spermatozoa can no longer fertilize the oocyte. So, given data from animal studies showing EVs from the female reproductive tract promote sperm maturation to increase fertilization chances, we would expect higher uptake of CV-EVs LH + 2 compared to LH + 7, if we consider that both have the same effect on spermatozoa.

All the EVs analysed do not negatively affect sperm viability and enhance the percentage of progressively motile spermatozoa; these results are comparable among different EVs sources and time points. Since spermatozoa exhibit variable efficiencies in capture EVs, eESCs-EVs would be expected to enhance sperm progressive motility more effectively than dESCs-EVs, considering the higher incorporation rate of the former compared to the latter20. A substantial inter-individual variability may account for the apparent absence of a direct correlation between the percentage of EVs uptake efficiency by sperm cells and the extent of EVs’ impact on sperm progressive motility. We can also consider the fact that the increase of progressive motility might reach a plateau, resulting in no further increments possible. In agreement with this hypothesis, the percentage of progressively motile sperm cells achieved through supplementation of HSA as a positive control, represents the highest achievable increase. Consequently, incubation with EVs captured by spermatozoa with lower efficiency, could have already raised the percentage of progressively motile spermatozoa to the maximum. As a result, incubation of spermatozoa with EVs incorporated with higher efficiency, do not induce a further significantly increase. On the other hand, the apparent discrepancy between EVs uptake efficiency and sperm motility enhancement may also be attributed to the distinct molecular cargo carried by each group of EVs. It is likely that EVs associated with relatively lower uptake efficiency, like CVF-EVs LH + 2, can still induce a certain increase in the percentage of progressively motile spermatozoa due to their specific cargo composition, which may be more effective in enhancing motility compared to EVs incorporated with higher efficiency. One example of such cargo is the cysteine-rich secretory protein-1 (CRISP1)31,32, shown to be significantly enriched in the EVs isolated from the seminal fluid of normozoospermic men (NS-EVs), which have positive effects on spermatozoa motility, compared to EVs from asthenozoospermic men (AS-EVs), which do not exhibit any positive effect33. Conversely, the proteome of AS-EVs was found to be enriched in glycodelin, a protein associated with primary infertility that inhibits albumin-induced cholesterol efflux from sperm cells, thereby preventing sperm capacitation34. We cannot exclude that CRISP1 and glycodelin can be part, as other regulatory proteins, of the proteome of FF-EVs, CVF-EVs and ESCs-EVs, determining heterogeneous EVs populations with similar abilities to induce functional effects on spermatozoa, despite the different efficiencies with which they are incorporated by sperm cells. These hypotheses may also explain the discrepancy between ESCs-EVs uptake efficiency and their effect on capacitation. Although eESCs-EVs were incorporated by sperm cells more efficiently than dESCs-EVs, spermatozoa incubated for 4 h with eESCs-EVs displayed a nearly identical percentage of acrosome-reacted sperm cells, indicating capacitation, as seen with dESCs-EVs. Importantly, these findings suggest that EVs from stromal endometrial cells consistently influence spermatozoa capacitation during both the proliferative and secretory phases of the endometrial cycle. After 4 h of incubation, CVF-EVs LH + 7 were those promoting capacitation in a higher percentage of spermatozoa, while CVF-EVs LH + 2 exerted the lowest effect on spermatozoa capacitation.

Collectively, the data presented in this study indicate that human spermatozoa are able to interact with FF-EVs, CVF-EVs LH + 2 and LH + 7, eESCs-EVs and dESCs-EVs, which may play a role in promoting aspects of sperm maturation. Remarkably, all EVs groups exhibited a similar impact on sperm motility, resulting in a significant increase in the percentage of spermatozoa displaying progressive motility. Additionally, all EVs groups contributed to sperm capacitation, with CVF-EVs LH + 7 showing slightly higher efficiency. This study therefore confirms the pivotal role of EVs in human reproduction, confirming observations made in animal models and emphasizing the contributions of EVs from different regions of the female reproductive to sperm maturation, encompassing capacitation and the enhancement of progressive motility.

Our experimental design was intended to simulate the early post-ejaculatory phase, during which spermatozoa are typically not yet capacitated. This condition was chosen to reflect the initial phase of interaction between sperm cells and extracellular vesicles within the female reproductive tract, particularly in regions such as the cervix and uterus. Future studies could evaluate also the EV uptake in spermatozoa that underwent capacitation, either through HSA supplementation or other established protocols, and provide valuable insights in determining whether the maturation state of sperm cells affects their ability to internalize EVs, especially in the context of FF-EVs, which spermatozoa would likely encounter at later stages during their transit through the oviduct.

Overall our findings might find application in ART cycles, during which spermatozoa do not enter in contact with the female reproductive tract which, in physiological conditions, complete their maturation. During ART cycles, a step of spermatozoa priming with EVs from different tracts of the female reproductive system could be included to better mimic spermatozoa’s physiological maturation, compared to standard in vitro maturation techniques.

Moreover, as recently proposed by E. Aleksejeva et al.35, human FF-EVs, CVF-EVs or ESCs-EVs could be employed during ART cycles to prime spermatozoa from asthenozoospermic men to increase the percentage of progressive motile spermatozoa, to enable IVF, rather than ICSI. Indeed, the latter is more expensive, demands a greater level of expertise and advanced laboratory equipment, and, most importantly, its safety remains uncertain. Furthermore, there is a scarcity of data supporting enhanced live birth outcomes with ICSI when compared to conventional IVF36. Thus, being able to favour IVF over ICSI through the priming of spermatozoa from severe AS men with EVs from different regions of the female reproductive would be a significant achievement. Further studies are needed to explore the feasibility and effectiveness of these female reproductive system-derived EVs applications in ART cycles.

Conclusions

Different regions of the female reproductive system produce and release EVs, which can be captured by spermatozoa and actively contribute in increasing the percentage of spermatozoa displaying progressive motility and promoting their maturation by supporting capacitation.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article.

Abbreviations

- IVF:

-

In Vitro Fertilization

- ART:

-

Assisted Reproductive Technology

- EVs:

-

Extracellular Vesicles

- FF:

-

Follicular Fluid

- CVF:

-

Cervicovaginal Fluid

- dESCs:

-

Decidualized Endometrial Stromal Cells

- eESCs:

-

E2-teated Endometrial Stromal Cells

- NS:

-

Normozoospermic

- NTA:

-

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis

- TEM:

-

Transmission Electron Microscopy

- UT:

-

Untreated spermatozoa incubated in non-capacitating basal BWW medium

- WOI:

-

Window of Implantation

References

Sullivan, R. & Saez, F. Epididymosomes, prostasomes, and liposomes: their roles in mammalian male reproductive physiology. Reproduction 146, R21–R35 (2013).

Ronquist, G. & Brody, I. The prostasome: its secretion and function in man. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 822 (2), 203–218 (1985).

Qamar, A. Y. et al. Extracellular vesicle mediated crosstalk between the gametes, conceptus, and female reproductive tract. Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 589117. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.589117 (2020).

Machtinger, R., Baccarelli, A. A. & Wu, H. Extracellular vesicles and female reproduction. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 38, 549–557 (2021).

Murdica, V. et al. Seminal plasma of men with severe asthenozoospermia contain exosomes that affect spermatozoa motility and capacitation. Fertil. Steril. 111, 897–908 (2019).

De Ferraz, A. M. M. Follicular extracellular vesicles enhance meiotic resumption of domestic Cat vitrified oocytes. Sci. Rep. 10 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65497-w (2020).

Hung, W. T., Hong, X., Christenson, L. K. & McGinnis, L. K. Extracellular vesicles from bovine follicular fluid support cumulus expansion. Biol. Reprod. 93, 117. https://doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod.115.132977 (2015).

Hung, W. T. et al. Stage-specific follicular extracellular vesicle uptake and regulation of bovine granulosa cell proliferation. Biol. Reprod. 97, 644–655 (2017).

Lopera-Vasquez, R. et al. Effect of bovine oviductal extracellular vesicles on embryo development and quality in vitro. Reproduction 153, 461–470 (2017).

Ferraz, M. A. M. M., Carothers, A., Dahal, R., Noonan, M. J. & Songsasen, N. Oviductal extracellular vesicles interact with the spermatozoon’s head and mid-piece and improves its motility and fertilizing ability in the domestic Cat. Sci. Rep. 9, 9484. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-45857-x (2019).

Franchi, A., Moreno-Irusta, A., Domínguez, E. M., Adre, A. J. & Giojalas, L. C. Extracellular vesicles from oviductal isthmus and ampulla stimulate the induced acrosome reaction and signaling events associated with capacitation in bovine spermatozoa. J. Cell. Biochem. 121, 2877–2888 (2020).

Sysoeva, A. et al. Characteristics of the follicular fluid extracellular vesicle molecular profile in women in different age groups in ART programs. Life (Basel). 14, 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/life14050541 (2024).

Deng, R. et al. Exosomes from uterine fluid promote capacitation of human sperm. PeerJ 12 (e16875). https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.16875 (2024).

Saint-Dizier, M. et al. Sperm interactions with the female reproductive tract: a key for successful fertilization in mammals. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 516, 110956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2020.110956 (2020).

Griffiths, G. S. et al. Investigating the role of murine epididymosomes and uterosomes in GPI-linked protein transfer to sperm using SPAM1 as a model. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 75, 1627–1636 (2008).

Al-Dossary, A. A., Strehler, E. E. & Martin-Deleon, P. A. Expression and secretion of plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase 4a (PMCA4a) during murine estrus: association with oviductal exosomes and uptake in sperm. PLoS One. 8, e80181. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0080181 (2013).

Lin, Y., Mahan, K., Lathrop, W. F., Myles, D. G. & Primakoff, P. A hyaluronidase activity of the sperm plasma membrane protein PH-20 enables sperm to penetrate the cumulus cell layer surrounding the egg. J. Cell. Biol. 125, 1157–1163 (1994).

Schuh, K. et al. Plasma membrane Ca2 + ATPase 4 is required for sperm motility and male fertility. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 28220–28226 (2004).

Hasan, M. M. et al. Bovine follicular fluid derived extracellular vesicles modulate the viability, capacitation and acrosome reaction of bull spermatozoa. Biology (Basel). 10, 1154. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10111154 (2021).

Murdica, V. et al. In vitro cultured human endometrial cells release extracellular vesicles that can be uptaken by spermatozoa. Sci. Rep. 10 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65517-9 (2020).

Viganò, P., Di Blasio, A. M., Dell’Antonio, G. & Vignali, M. Culture of human endometrial cells: a new simple technique to completely separate epithelial glands. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 72, 87–92 (1993).

Martinez, R. M. et al. Body mass index in relation to extracellular vesicle-linked MicroRNAs in human follicular fluid. Fertil. Steril. 112, 387–396e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.04.001 (2019).

World Health Organization. World Health Organization WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen 6th edn (WHO, 2021).

Welsh, J. A. et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): from basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 13, e12451. https://doi.org/10.1002/jev2.12404 (2024).

Jia, Y. et al. Small extracellular vesicles isolation and separation: current techniques, pending questions and clinical applications. Theranostics 12, 6548–6575 (2022).

Théry, C. et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the international society for extracellular vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 7, 1535750. https://doi.org/10.1080/20013078.2018.1535750 (2018).

Hammitt, D. G., Walker, D. L. & Williamson, R. A. Survival and in vitro fertilization potential of sperm following washing and incubation with different protein supplements. Int. J. Fertil. 35, 46–50 (1990).

Villani, M. T. et al. Are sperm parameters able to predict the success of assisted reproductive technology? A retrospective analysis of over 22,000 assisted reproductive technology cycles. Andrology 10, 310–321 (2022).

Lin, Y. P., Chen, W. C., Cheng, C. M. & Shen, C. J. Vaginal pH value for clinical diagnosis and treatment of common vaginitis. Diagnostics (Basel). 11, ; (1996). https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11111996 (2021).

Mulcahy, L. A., Pink, R. C. & Carter, D. R. Routes and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle uptake. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 3 https://doi.org/10.3402/jev.v3.24641 (2014).

Ernesto, J. I. et al. CRISP1 as a novel CatSper regulator that modulates sperm motility and orientation during fertilization. J. Cell. Biol. 210, 1213–1224 (2015).

Da Ros, V. G. et al. From the epididymis to the egg: participation of CRISP proteins in mammalian fertilization. Asian J. Androl. 17, 711–715 (2015).

Murdica, V. et al. Proteomic analysis reveals the negative modulator of sperm function Glycodelin as over-represented in semen exosomes isolated from asthenozoospermic patients. Hum. Reprod. 34, 1416–1427 (2019).

Chiu, P. C. et al. Glycodelin-S in human seminal plasma reduces cholesterol efflux and inhibits capacitation of spermatozoa. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 25580–25589 (2005).

Aleksejeva, E. et al. Extracellular vesicle research in reproductive science: paving the way for clinical achievements. Biol. Reprod. 106, 408–424 (2022).

Balli, M. et al. Opportunities and limits of conventional IVF versus ICSI: it is time to come off the fence. J. Clin. Med. 11, 5722. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11195722 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Part of this work was carried out in the Advanced Light and Electron Microscopy BioImaging Center (ALEMBIC) of San Raffaele Scientific Institute. This study has been partially supported by Amici di URI Onlus.

Funding

This work was partially supported by Amici di URI Onlus.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CF conducted the experimental work, contributed to analyse the data and wrote the manuscript. EG and VP contributed to experimental design, supervised human subject recruitment and the experimental work, and gave intellectual input to data interpretation. LSN gave intellectual input to manuscript writing. VB, LP, PG, LB, and MS were responsible for subject recruitment and sample collection. LP contributed to experimental design, analysed the data and gave intellectual input to data interpretation. EP, MC and AS supervised subject recruitment. RV conceived and designed the study, supervised the experimental work and gave intellectual input to manuscript writing.All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained by the Institutional ethical committee (BC-GINEOS, date of approval: 09/02/2012, San Raffaele Hospital Ethics Committee) and subjects involved provided a written informed consent. The work was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fasoli, C., Giacomini, E., Pavone, V. et al. Extracellular vesicles from different regions of the female reproductive tract promote spermatozoa motility and support capacitation. Sci Rep 15, 25917 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11712-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11712-5