Abstract

The production of hexamethylene-1,6-diisocyanate (HDI) via carbamate cracking avoids the use of phosgene; however, the environmental impact of this non-phosgene synthesis route has not been thoroughly studied. Conventional process simulations typically focus solely on economic indicators, which may overlook important environmental considerations. We have developed a multi-objective optimization framework that collectively accounts for total annual cost, green degree and total energy consumption for such a non-phosgene synthesis process of HDI. We used data from rigorous simulations to construct a surrogate model based on artificial neural networks. This model simplifies the numerical correlation among optimization objectives and process/operational parameters. The bat algorithm was employed for multi-objective optimization on such surrogate models with significantly reduced computational burden, resulting in a series of optimal solutions as the Pareto front. The optimal solution exhibits a 28.79% reduction in total energy consumption and a 19.72% reduction in the total annual cost compared to the real-world production data; the green degree of the optimized process is increased by 21.60%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Isocyanates are value-added chemicals with various industrial applications as exemplified by serving as feedstocks for polyurethane production1,2. The isocyanate market size is estimated at 16.56 million tons in 2024, and it is expected to reach 22.41million tons by 20293. Currently, the majority of isocyanates are produced through phosgene-involved reactions, posing significant risks to both the environment and human health4. The thermal cracking of N-substituted carbamates is known as the alternative phosgene-free approach5, but it is still not as economically competitive as the conventional phosgenation process4. Moreover, the environmental impact of such phosgene-free synthetic route remains unclear.

Hexamethylene-1,6-diisocyanate (HDI) is one of the most significant aliphatic diisocyanates, and the related research has focused on the synthesis and thermal cracking of hexamethylene dicarbamate6,7. For process optimization, Hsu et al. studied the optimized total annual cost of the distillation process for hexamethylene dicarbamate synthesis8. Wang et al. proposed the reactive distillation-vapor recompression integrated process for dicarbamate synthesis with reduced total operation cost and annual cost9. Comparatively, the optimization of the environmental impact of the HDI production process has not been reported, let al.one the synergistic optimization of production costs and environmental impact. The green degree is an integrated index composed of nine environmental impact categories including global warming and toxicological effects10. This index provides a quantitative assessment of the environmental impacts associated with chemical processes. Although the determination of weighting factors for environmental impact categories remains challenging, the green degree integrated with process simulation techniques provide a useful environmental assessment tool for chemical processes, with successful applications in chemical process design11,12,13process evaluation and optimization14,15,16,17solvent screening18,19. We consider the green degree as an appropriate metric for evaluating the environmental impact of the HDI production process. The reason is that it not only assesses the toxicity of various substances generated during HDI production but also reflects the greenhouse gas effects of high-energy consumption units such as distillation and pyrolysis involved in HDI production. In this context, a multi-objective optimization (MOO) framework can be constructed for the HDI production process to simultaneously optimize the production costs and the green degree. Indeed, the green degree of energy is calculated by converting the system’s energy consumption into the green degree of greenhouse gases produced by corresponding specific utilities (e.g., coal and natural gas). To clearly reveal the factors influencing the energy consumption of the HDI production, the total energy consumption was considered as a third objective other than total annual cost and green degree for MOO.

The integration of first principles models with optimization algorithms is widely adopted for addressing MOO problems in chemical processes20,21,22. For the non-phosgene HDI production, the rigorous models of units such as methoxycarbonylation, thermal cracking and distillation comprise a large number of nonlinear equations due to complex thermodynamics and kinetics. Solving these equations already demands significant computational workload; when optimization algorithms are employed for multiple iterations, the overall computational workload becomes even larger23. Recently, machine learning approach has been used to develop surrogate models for the MOO of complex processes24,25. Machine learning is categorized into supervised, semi-supervised, unsupervised and reinforcement learning26,27. Surrogate models that approximate and replace actual models are considered as supervised machine learning. They are notable for reducing computational demands and minimizing costly engineering expenses. Therefore, the surrogate model-based optimization technique can be viewed as an effective framework that integrates machine learning with optimization algorithms. Common surrogate models include the polynomial response surface method28, Kriging method29, support vector regression30, radial basis function31, Gaussian process regression32 and artificial neural network (ANN)33. Among these techniques, ANN has been recognized for its reduced demand for computational resources34,35,36. ANN-based surrogate models offer several advantages for modeling complex industrial processes: (i) construction using only historical process data without requiring detailed phenomenological knowledge, (ii) strong generalization capability for accurate predictions on new operating conditions, and (iii) the ability to efficiently capture multiple nonlinear input-output relationships simultaneously. These characteristics make ANNs particularly well-suited for identifying and modeling the complex nonlinear behavior inherent in this study. For the complex process simplified using an ANN-based surrogate model, the genetic algorithm is commonly employed for MOO37,38,39. The swarm intelligence algorithm is a metaheuristic algorithm that mimic the animal movement or the hunting behavior40. It has efficient and parallel global optimization capabilities and strong optimization performance, and has been applied in MOO in processes such as reactive distillation41, pressure swing adsorption42 and heat exchanger design43.

Herein, we report an ANN-assisted MOO framework to optimize the HDI process considering total annual cost, total energy consumption and green degree by using a surrogate model based on ANN in conjunction with optimization algorithms. The objective values under different process/operation parameters were obtained through rigorous simulation. The ANN was used to construct the mathematical correlation between parameters and objective values to form a surrogate model. We employed the bat algorithm to directly perform MOO on such a surrogate model, resulting in a set of Pareto solutions. The technique for ordering preferences on similarity of ideal solutions (TOPSIS) was used for decision-making on the Pareto front to determine the optimal solution for HDI production. The Sobol method was used for sensitivity analysis to investigate the impact of process parameters on different objectives. The reflux ratio and the tray number of the distillation unit was then identified as the significant factors for economic and environmental performance of HDI production process.

Methods

General framework

In this study, we propose a framework using an artificial neural network to assist in multi-objective optimization (ANN-MOO). The goal is to simultaneously minimize the total annual cost (TAC) and total energy consumption (TEC) while maximizing the green degree (GD) of the HDI process. Figure 1 illustrates the process optimization steps. In Step 1, we developed a steady-state mechanistic model of the HDI process using Aspen Plus. This model was validated against industrial data to ensure accuracy. Step 2 involves deriving decision variables from process parameters. We then constructed surrogate models based on ANN to predict the objective values and ensure the convergence of the HDI process. The accuracy of these models was thoroughly evaluated. In Step 3, we applied the bat algorithm to integrate the surrogate models from Step 2. The algorithm optimizes the HDI process with the objectives of minimizing TAC and TEC while maximizing GD, resulting in a solution set as the Pareto front. In Step 4, we employed the TOPSIS method to select the optimal solution from the Pareto front. This solution is re-integrated into the rigorous model developed on Aspen Plus and compared with the current operational scheme to verify the effectiveness and applicability of the proposed framework.

Optimization objective

Total annual cost

Total annual cost (TAC) is commonly utilized as an economic indicator for evaluating a process. It is estimated by Eq. (1):

The TAC includes both capital investment (CI) and operating cost (OC). The CI was calculated by summing the expenses for equipment such as the distillation tower, stages, reboiler, condenser and reactor, and these costs were spread over a three-year payback period. The OC includes expenses for electricity, recycling water and steam. The annual operating cost was calculated based on 8000 working hours with the Marshall and Swift (M&S) index of 2176.6. The detailed calculation process can be obtained from the supporting information.

Green degree

This study used the green degree (GD) method as an assessment of environmental impact10. The green degree (GD) is an integrated environmental impact evaluation index. It considers nine environmental impact categories to comprehensively estimate the environmental performance: global warming potential (GWP), ozone depleting potential (ODP), photochemical ozone creation potential (POCP), acidification potential (AP), eutrophication potential (EP), ecotoxicity potential to water (EPW), ecotoxicity potential to air (EPA), human carcinogenic toxicity potential to water (HCPW), and human non-carcinogenic toxicity potential to water (HNCPW). The GD includes the GD of material and the GD of energy. The GD of material mainly refers to the degree of harm or impact on the environment caused by physical and chemical changes in substances. The environmental impact index of raw materials, auxiliary media, products, and wastes in the process of change needs to be considered in the quantitative calculation of their GD. The GD of energy includes the environmental impact of the waste and energy emitted during the production process.

The calculation of GD comprises three fundamental components: substance GD, energy GD, and process GD. Substance GD is quantified through a systematic procedure involving the normalization of nine environmental impact potentials associated with the substance, followed by their multiplication with corresponding weighting factors and subsequent summation. Energy GD is derived from the quantitative assessment of waste emissions resulting from the utilization of specific energy sources. The process GD is ultimately determined by integrating the GD values of all material and energy flows (both input and output) within the established system boundaries, thereby yielding the comprehensive GD evaluation for the entire industrial process. The details of GD calculation for HDI process are provided in Supporting Information. Finally, the simplified GD of the HDI process is as shown in Eq. (2)11:

where \(\:\sum\:{GD}^{process}\) is calculated from the GD value of each substance component; the GD values of substances involved in this work are listed in Table S2; \(\:\sum\:{GD}^{energy}\) results from the process energy consumption; and the GD values of different fuel sources are provided in Table S3. The larger the \(\:{GD}^{process}\) value, the better the environmental performance would be. If \(\:{GD}^{process}\) is positive, it indicates that the process is environment-friendly; on the contrary, \(\:{GD}^{process}\) represents that the process causes some harmful influence on the environment.

Total energy consumption

The law of mass & energy conservation is the basis of energy analysis, which is expressed as Eqs. (3) and (4)44:

where m is the mass flow rate, Q is the heat transfer rate, W is power, and h is the specific enthalpy. The energy analysis calculations were performed using Aspen Plus process simulation software. The computations were based on steady-state assumptions with no mass accumulation in the system, while vapor-liquid phase equilibrium was described by appropriate thermodynamic models. All mass and energy balance equations for the operating units were automatically solved and verified by Aspen Plus.

In this study, the energy-consuming equipment includes the reboiler of the distillation column and reactors. Therefore, the total energy consumption (TEC) was considered as the primary objective for energy consumption analysis, which can be calculated according to the Eq. (5).

Where \(\:{Q}_{reboilor}\) is the heat load of the reboiler. \(\:{Q}_{reactor}\) is the heat load of the reactor.

Surrogate model based on ANN

The construction steps of the ANN-based surrogate model are illustrated in Fig. 2. First, the sample dataset required for training the ANN model is obtained. After data preprocessing, MATLAB is employed to develop ANN-based surrogate models with varying network architectures. The optimal network structure is then determined by comparing the performance of different configurations. The resulting surrogate model can subsequently be utilized for multi-objective optimization.The code is available at https://gitlab.hk/lb-group/LB-project.git.

Data acquisition and pre-processing

To effectively train and test an ANN model, it is crucial to generate or collect a data set in which more input-output data points lead to better predictions and improved generalization. When data acquisition is computationally expensive or time-consuming, a balance must be maintained between data set size and prediction accuracy. In this study, the Latin hypercube sampling (LHS) method45 was employed to generate a sample set of 10,000 samples.

To reduce the differences in ranges and units among different variables, it is necessary to perform data normalization during the modeling process46. This study employed the rescaling method for normalization as described in Eq. (6):

Where \(\:{X}_{i}\) is the set of data in the dataset, \(\:{S}_{i}\) is the normalized dataset of \(\:{X}_{i}\), \(\:\text{max}\left(X\right)\) and \(\:\text{m}\text{i}\text{n}\left(X\right)\) are respectively the maximum and minimum values in \(\:{X}_{i}\).

The proportions of the training set, test set and validation set were set to 70%, 15% and 15%, respectively47. The maximum number of iterations was set to 8000.

Details of ANN modeling

The ANN utilized in this study consists of an input layer, several hidden layers and an output layer (Fig. 3). The input layer receives a vector of predicted variable values \(\:X\). As values propagate through each neuron in the hidden layers, they are processed via weights and biases, then passed through an activation function and sent the result to the next layer until arrived at the final output value \(\:Y\). Initially, the model’s weights and biases are randomly assigned. To improve accuracy, these parameters are iteratively updated using a gradient descent algorithm, adjusting from the output layer back through the hidden layers until the error is reduced to an acceptable level. During the above process, the training set is directly employed to train the model by updating the weights and biases via backpropagation algorithms. The validation set is utilized to monitor the model’s performance in real-time during training (e.g., loss values after each epoch), enabling early stopping to prevent overfitting and facilitating hyperparameter tuning (e.g., learning rate, regularization parameters). Finally, the model’s generalization capability is rigorously evaluated using the test set.

In this study, MATLAB software and the ‘feedforward’ function were utilized for modeling. The network was trained using a back-propagation method with the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm implemented via the ‘Trainlm’ function. The sigmoid function was selected as the activation function. The accuracy of the objective function significantly influences the outcomes of MOO, making it crucial to design an optimal model architecture, particularly regarding the number of neurons in the hidden layer. Less neurons make the learning process unreliable, while too many neurons lead to increased computational time and the overfitting the model48. However, there is no specific method for determining the number of neurons in the hidden layer49. To simplify the modeling process, a uniform number of neurons is used in the hidden layers. In this study, the number of neurons was determined using the empirical Eq. (7)50:

where\(\:{N}_{h}\) is the number of neurons in the hidden layer, \(\:{N}_{X}\) refers to the number of input layers, \(\:{N}_{Y}\) denotes the number of output neurons, and \(\:a\) is the constant between 1 and 10.

Evaluation metrics

The performance of the surrogate models was evaluated using the coefficient of determination (\(\:{R}^{2}\)) and mean squared error (\(\:MSE\)), as shown in Eqs. (8) and (9):

where \(\:{y}_{i}\) is the \(\:{i}^{th}\) observed label value, \(\:{\widehat{y}}_{i}\) is the \(\:{i}^{th}\) estimated label value, \(\:\stackrel{-}{y}\) is the mean of the observed label values, and \(\:N\) is the number of observed label values. In general, \(\:{R}^{2}\) indicates the proportion of variance explained by the model and the strength of correlation in the prediction process. \(\:MSE\) serves as an error indicator that offer a measure in the same units as the target variable51. A smaller \(\:MSE\) value signifies better predictive accuracy of the surrogate model. Similarly, an \(\:{R}^{2}\) value closer to 1 reflects a higher degree of fit and improved predictive accuracy of the surrogate model.

Optimization methods

Bat algorithm

The update formulas of the bat algorithm (BA)52 are inspired by the predatory behavior of bats, where the prey symbolizes the optimal solution. The details of the BA can be found in the supporting information. The flowchart of the BA is displayed in Fig. 4 The parameter settings for the algorithm are detailed in Table 1.

Decision-making in multi-objective optimization

The solution set on the Pareto front is derived using the ANN-MOO framework, which offers a range of trade-offs among competing objectives. Each point in the set is equally viable, requiring additional information to identify the optimal point. Consequently, the TOPSIS method was employed to determine the optimal solution by evaluating the similarity between the solution set and the ideal solution50,53. The detailed calculation of the TOPSIS is provided in the supporting information.

Sensitivity analysis

To identify the most influential parameters within the HDI process, we utilized the Sobol sensitivity analysis method. The Sobol method, which relies on variance decomposition, is a form of global sensitivity analysis commonly used to evaluate the sensitivity of parameters in nonlinear models54. The Sobol method fundamentally involves breaking down a model into a series of functions that depend on either individual parameters or combinations thereof. This approach enables the assessment of parameter sensitivity and interactions by evaluating how the variance of individual input parameters or sets of parameters impacts the overall output variance. This analysis includes the computation of the first-order and total-order Sobol indices55,56. When the first-order index (\(\:{S}_{i}\)) has a higher value, the corresponding input parameter has a greater impact on the output in comparison to other inputs. The total-order sensitivity index (\(\:{S}_{{T}_{i}}\)) represents the comprehensive influence of input parameter \(\:{X}_{i}\), encompassing not only the first-order effects but also all higher-order interaction effects that involve \(\:{X}_{i}\). A higher value of \(\:{S}_{{T}_{i}}\) indicates that \(\:{X}_{i}\) plays a more crucial role as an input for \(\:Y\). In this study, TAC, GD and TEC were considered as the performance criteria in the sensitivity analysis. The details of the Sobol method can be found in the supporting information.

Results and discussions

First principles modeling of the HDI process

In this study, Aspen Plus was applied to simulate the HDI process. The flowsheet for the HDI production and the main industrial data from a chemical company in Shanxi, China. The WILSON method was chosen as the physical method for the separation of dimethyl carbonate and methanol57while The NRTL method was chosen for the other processes in HDI production8,9. The RSTOIC block was selected for the reactor unit and the Radfrac block was chosen for the distillation column unit. The Sep block was used to separate solid salts and liquid mixture. When the duty was set to zero, the flash block was applied to simulate the storage tank. Additionally, any missing properties and binary interaction parameters were estimated using the estimation function of Aspen Plus. The process was based on the following assumptions:

(1) Steady-state operation and pressure drops were neglected for all equipment.

(2) Catalyst activation and coking were not considered.

(3) All gases are assumed to behave ideally, and heat loss from the components to the atmosphere is neglected.

The fundamental production process is illustrated in Fig. 5 Initially, a mixture consisting of hexamethylenediamine (HDA), dimethyl carbonate (DMC) and recycled DMC, with a DMC/HDA molar ratio of 4:1, is fed into Reactor 1 for the methoxycarbonylation reaction. A filter then isolates hexamethylene dicarbamate (HDC) as the intermediate product from the reaction mixture. The purified HDC was transported to next stage. Simultaneously, the remaining liquid mixture is combined with the gaseous product and is directed to a pressure-swing distillation unit for the separation of DMC and methanol. The high-pressure column produces a bottom stream containing 99.5 wt% DMC, which is recycled and combined with fresh HDA for Reactor 1. The low-pressure column extracts methanol with a purity of 99.5 wt %.

Stream S7, containing HDC, is mixed with fresh o-dichlorobenzene (ODCB) and introduced into the thermal decomposition reactor, referred to as Reactor 2. The gaseous output from Reactor 2 is sent to the DC1 column for the removal of byproduct methanol and some ODCB. These byproducts are then transferred to another distillation column, DC2, for further purification. The liquid product from DC1 moves to the DC3 column, where additional ODCB is separated. This separated ODCB is combined with the bottom stream from DC2 and recycled back to Reactor 2. The bottom stream from DC3 was sent to the next column (DC4) for final product purification. The bottom stream of DC4 contains unreacted intermediates, which can be redirected to Reactor 2 for further processing. The top stream yields the high-purity HDI product with the purity of 99.8 wt%. The process simulation results were compared with the industrial data, and the relative errors between the three stream products (S18, S30, S32) and the industrial data (S18*, S30*, S32*) are negligible (Table 2), demonstrating that the HDI process simulated in Aspen Plus is reliable for process analysis and optimization.

Decision variables and constraints

The HDI process comprises numerous variables including over 30 major streams and equipment parameters. Variable selection is conducted by evaluating the convergence performance of different parameter combinations. Ultimately, this study identified 12 independent variables associated with the distillate flow rates, total plate numbers and reflux ratios of the main columns shown in Fig. 5 The ranges for these variables were established to enable regular equipment operation and ensure successful convergence of the simulation process (Table 3). A set of constraints were used to confine the optimization in the desired direction as shown in Eq. (10). The partial input variables generated by the algorithm lead to un-converged and infeasible simulation results during iterations. As a consequence, larger penalty was applied to the objective function for un-converged simulation and the associated infeasible solutions were replaced during the optimization process.

\(\:{MF}_{S16\_DMC}\), \(\:{MF}_{S18\_Methanol}\), \(\:{MF}_{S30\_Methanol}\) and \(\:{MF}_{S32\_HDI}\) represent the mass fraction of the DMC, methanol and HDI in their own product stream S16, stream S18, stream S30 and stream S32.

Result of the surrogate model

A dataset of 10,000 samples (Table S4 of.xlsx file) were utilized to build a surrogate model aimed at predicting convergence of process simulation, in which 6,358 converged samples (Table S5 of.xlsx file) were then used as the input for the objective value surrogate model, with each sample producing three objective values as output.

Two surrogate models were established: one to predict model convergence and the other for predicting the objective values. The surrogate model of convergence uses 12 process parameters as input and provides a binary output, where 0 indicates non-convergence and 1 indicates convergence. Therefore, the “fitcnet” function was utilized to train a neural network binary classification model, and the final training results of the convergence model are shown in Table 4. A prediction accuracy of 0.7305 demonstrates that the trained convergence model effectively predicts convergence within the decision variable space.

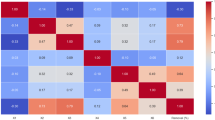

The surrogate model for predicting the objective value was developed using the methodology outlined in the Section "Surrogate model based on ANN". To explore various hyperparameter options for the neural network, all potential architectures were generated based on the criteria in Table 5. Different ANN models, with varying numbers of neurons and hidden layers, were trained and statistically assessed using a trial-and-error approach. After training and validating the ANN models, the mean squared error of all predicted data for test set were compared. As shown in Fig. 6, a parametric study was conducted to determine the neuron and hidden layer configuration that minimizes prediction error.

According to Fig. 6, the neural network with three hidden layers and 12 neurons achieves the lowest mean squared error, indicating minimal deviation from the simulation results. Fewer than 6 neurons results in underfitting and information loss, while more than 12 neurons leads to overfitting and noise memorization.

The ANN composed of three hidden layers with 12 neurons presents the best performance among all the ANN models (Fig. 7). Figures 8a-c show that the regression between the ANN model’s predictions and the Aspen Plus simulation data has strong level of agreement. The data points are tightly clustered along the central line in the regression plots. The coefficients of determination R2 of the ANN model are 0.98886, 0.99996 and 0.99996 for the TAC, TEC and GD, respectively. The mean squared error values are 1.57245, 0.14187 and 0.11556 for the TAC, TEC and GD, respectively. The error histogram (Figs. 8d-f) exhibits that model predictions have errors close to zero and follow a normal distribution. Based on the results, the surrogate model shows high precision and stability in estimating the HDI process’s TAC, TEC and GD values, rendering it an effective tool for supplying accurate objective functions in multi-objective optimization algorithms.

Multi-objective optimization results

Computational efficiency

Figure 9 illustrates the convergence results of optimizing the HDI process with the ANN-MOO framework. Notably, the optimization process achieves similar convergence outcomes when Itermax is set to 250, 300 and 350. This suggests that the optimization process fully converges by Itermax of 350, and further increases in Itermax do not significantly improve the results.

Figure 10 presents the composition of optimization time. Significantly, the most time-intensive process within the proposed ANN-MOO framework is data collection for the HDI process because of the frequent invocations of Aspen Plus. Invoking Aspen Plus for a single fitness evaluation takes approximately 15 s. Therefore, optimizing the HDI process without the use of surrogate model requires approximately 145.9 h. In contrast, the ANN-MOO framework significantly reduces this time by requiring only 42.3 h for data collection, 1.48 h for training the ANN model and optimizing hyperparameters, and just 0.26 h for MOO through the BA. The key advantage of the proposed framework is to achieve the Pareto front solution without repeatedly invoking the complex models for solution and verification. This approach results in a substantial reduction of 71% in computing time. Therefore, the computational efficiency is remarkably enhanced when optimizing the HDI process with the ANN-MOO framework.

The analysis of MOO results

Figure 11a illustrates the Pareto front achieved through the ANN-MOO framework. Once the Pareto front is established through optimization, its validity needs to be assessed. To verify this, 785 random samples were generated and compared against the Pareto front. Neither the random samples nor the dataset values surpassed the solutions on the Pareto front. The consistency between the Pareto front from the ANN-MOO framework and ANN-free MOO framework (Fig. 11b) reflect the reliability of the ANN as a surrogate model for the HDI process within the design space.

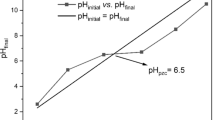

The HDI process developed in this study imposes constraints on flow rates and product purity, resulting in relatively small variations in the material GD of the HDI process. According to Eq. (5), the energy consumption of the HDI process is negatively correlated with GD, which corresponds to the results shown in Fig. 12a of the Pareto front. We observe that a reduction in TEC leads to an increase in TAC (Fig. 12b). The heat load of the distillation reboiler and reactor constitute the main components of TEC. Taking the distillation column as an example, when TEC is relatively low, the heat load of the reboiler is also reduced. To maintain separation efficiency, the number of trays in the distillation column increases, resulting in an increase in equipment investment within TAC that far exceeds the decrease in operating costs due to lower energy consumption. Due to the inverse mathematical relationship between GD and TEC, GD is the positively correlated with TAC (Fig. 12c). The three-dimensional Pareto front with TAC, GD and TEC as objectives is illustrated in Fig. 12d. The TAC, GD and TEC range from 92.55 × 104 to 105.85 × 104 $/year, −303.97 × 104 to −289.59 × 104 gd/year and 221.96 × 102 to 239.08 × 102 GJ/year, respectively. In order to systematically evaluate the trade-offs among these conflicting objectives, the TOPSIS method was employed to identify the most advantageous solution (Table S6 of.xlsx file). The most favorable solution for the HDI process under study is represented by the red-filled circle in Fig. 12d.

The optimal solution for the HDI process shows TAC, GD and TEC values of 94.27 × 104 $/year, −294.59 × 104 gd/year and 227.85 × 102 GJ/year, respectively. Compared with the actual operating point in Table 6, after optimization using the proposed ANN-MOO framework, the HDI process achieved a 19.72% reduction in TAC, a 21.60% increase in GD and a 28.79% reduction in TEC. This indicates a well-balanced performance across economic, environmental and energy metrics. Currently, there are no reported studies on the GD of the HDI production process. Under optimal conditions, the GD of the HDI production process is calculated as −2.05 gd per kilogram of product. As far as we know, there are two reported cases regarding the calculation of GD for the whole chemical production process: the GD of methyl methacrylate production is approximately 0.64 gd per kilogram of product10and the GD of CO2 conversion process to dimethyl carbonate is 0.07 gd per kilogram of product58. Although both processes include energy-intensive separation units, the low-GD raw materials were converted to high-GD products, so that the green degree of the whole production process was guaranteed. Similarly, the HDI production involves multiple distillation processes; but the use of non-phosgene raw materials and the aliphatic nature of HDI with lower environmental impact compared to aromatic counterparts result in a substance GD that offset the negative impact of high energy consumption on GD. Therefore, the GD per kilogram of HDI is relatively close to other two products reported in the literature. Moreover, after optimization, the GD of the distillation unit in the HDI production process is −0.75 gd per kilogram of product, which is better than the reported GD of azeotropic distillation separation (−1.22 gd per kilogram of product) and ionic liquid extraction (−37.76 gd per kilogram of product)13,59.

To assess the reliability of the proposed ANN-MOO framework, we input the optimal solution determined by TOPSIS into Aspen Plus for simulation. Table 7 presents the convergence results and key stream outcomes from Aspen Plus under optimal process parameters. The simulation result shows that the optimal solution obtained through the TOPSIS method meets the flow and purity requirements of the HDI product. Additionally, the differences in TAC, GD and TEC values between the rigorous model and the ANN surrogate model are minimal, highlighting the effectiveness of the ANN surrogate model for the HDI process.

Sensitivity analysis results

The global sensitivity analysis was conducted using the Sobol method, which is based on the decomposition of variance in the model output, to evaluate the contributions of each input variable to the model output. Figure 13 shows the first-order index (\(\:{S}_{i}\)) and total-order index (\(\:{S}_{Ti}\)) for TAC, GD and TEC, respectively. Based on the \(\:{S}_{i}\) and \(\:{S}_{Ti}\), V11 (C-203 distillate feed ratio) is identified as the most influential input parameter for TAC (Fig. 12a). In addition, the \(\:{S}_{i}\) of V5 (C-101 pressure), V6 (C-102 number of trays), V7 (C-102 mass reflux ratio) and V8 (C-102 feed tray number) also indicate a significant impact on the TAC of the HDI process. While the \(\:{S}_{i}\) of V12 (C-202 distillate feed ratio) for TAC is small, the \(\:{S}_{Ti}\) is significantly larger than \(\:{S}_{i}\). The differences between the \(\:{S}_{i}\) and the \(\:{S}_{Ti}\) indicate the greater impact of interactions among input variables on objective values compared to the effects of individual input variables. The insignificancy of \(\:{S}_{i}\) and \(\:{S}_{Ti}\) for the remaining input are reflected by the near-zero value. Figures 13b-c indicate that the variables V5, V6, V7, V8 and V11 also have a significant impact on GD and TEC. The influence of the remaining variables on GD and TEC is relatively minor. However, the Sobol index values for V9 (C-203 number of trays) show a more pronounced influence on TAC than on GD and TEC. It can be attributed to the fact that the number of trays directly influences the capital costs associated with the equipment.

The C-101 pressure, C-102 number of trays, C-102 feed tray number and C-203 distillate feed ratio are the most significant parameters for the HDI process based on the Sobol method. Therefore, the influence of these parameters on TAC, GD and TEC is further analyzed. Figure 14 shows the optimized operating parameters of the significant variables corresponding to the Pareto-optimal front. Figure 14a depicts the value of C-101 pressure corresponding to the Pareto point. The optimal points are mainly concentrated around 13 atm, which is close to the upper limit of the decision variables. This is because higher C-101 column pressure facilitates the separation of methanol and DMC60, thereby reducing the reboiler load and related operation cost. Moreover, the reduction in reboiler load also leads to a decrease in the reflux in the pressure swing distillation section, thereby reducing the overall heating load and enhancing the GD of the HDI process.

Figures 14b-c show that the C-102 number of trays and C-102 feed tray number exhibit similar distribution trends at the Pareto points, with values of 30, [35, 50] and 10, [14, 26], respectively. This indicates a strong interaction between these two parameters. When the C-102 number of trays is 30, the C-102 feed tray number consistently has a value of 10, and similar correspondences are observed for the other intervals. Reducing the number of trays results in decreased separation efficiency, which in turn increases the reboiler load and associated energy consumption. The increase in energy consumption further leads to a reduction in the GD of the HDI process.

Figure 14d illustrates the optimal values of the C-203 distillate feed ratio. The values at the Pareto points are primarily distributed around the lower limit of 0.78. The C-203 column involves multiple recycle streams and complex interactions with other variables. Reducing the distillate feed ratio not only decrease the recycle flow of the HDC pyrolysis process, but also reduce overall energy consumption/operating costs and increase the GD of the HDI process. Therefore, maintaining the C-203 distillate feed ratio at the lower operating limit is beneficial for the HDI process.

Conclusion

This study presents an artificial neural network-assisted multi-objective optimization framework of HDI production process for improved the economic, energy and environmental performance. The TOPSIS method was employed to facilitate decision-making along the Pareto front, leading to the identification of the optimal configuration. The key findings were summarized as follows:

(1) The ANN-based surrogate model was built to predict the convergence and various objective values of the HDI process. The results demonstrated that the convergence model has an accuracy of 0.7305, and the R2 values for the objective models corresponding to TAC, TEC and GD are 0.98886, 0.99996, and 0.99996, respectively. The corresponding mean squared error values for the objective models are 1.57245, 0.14187 and 0.11556. The above results demonstrate the accuracy of the surrogate models.

(2) The ANN-assisted MOO framework was established to optimize the HDI process. The results show a remarkable reduction of 71% of the computational time compared to rigorous process simulation. The solving time of the multi-objective optimization for the HDI process can be shortened from 145.9 h to 42.3 h with the premise of accuracy by using the surrogate model. An optimal solution was selected by the TOPSIS method from the Pareto front. Compared with the actual operating conditions, the TAC and TEC can be respectively reduced by 19.72% and 28.79% when the GD increases by 21.60% under the optimal scheme.

(3) Sensitivity analysis indicated that the C-101 pressure, C-102 number of trays, C-102 mass reflux ratio, C-102 feed tray number and C-203 distillate feed ratio are the most influential parameters for TAC, TEC and GD.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Huuskonen, P. et al. Occupational exposure and health impact assessment of diisocyanates in Finland. Toxics 11, 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics11030229 (2023).

Lenzi, V., Crema, A., Pyrlin, S. & Marques, L. Current Dtate and perspectives of simulation and modeling of aliphatic isocyanates and polyisocyanates. Polym 14, 1642. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14091642 (2022).

MorDorIntelligence. Isocyanates Market Volume & Share Analysis - Growth Trends & Forecasts (2024–2029). https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/isocyanates-market (2024).

Delavarde, A. et al. Sustainable polyurethanes: toward new cutting-edge opportunities. Prog Polym. Sci. 151, 101805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2024.101805 (2024).

Wang, P., Liu, S. & Deng, Y. Important green chemistry and catalysis: Non-phosgene syntheses of isocyanates-thermal cracking way. Chin. J. Chem. 35, 821–835. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjoc.201600745 (2017).

Cao, Y. et al. Non-phosgene synthesis of hexamethylene-1,6-diisocyanate from thermal decomposition of hexamethylene-1,6-dicarbamate over Zn–Co bimetallic supported ZSM-5 catalyst. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 27, 549–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjche.2018.05.001 (2019).

Cao, J. et al. Efficient synthesis of dimethyl hexane-1,6-dicarbamate via methoxycarbonylation of 1, 6-hexanediamine with Methyl carbamate over acid-base enhanced CeO2. Mol. Cata. 549, 113453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcat.2023.113453 (2023).

Hsu, C. M., Wang, S. J., Chen, Y. T. & Wong, D. S. H. Novel separation process design for non-phosgene dimethylhexane-1,6-dicarbamate synthesis by reacting dimethyl carbonate with 1,6-hexanediamine. J. Taiwan. Inst. Chem. Eng. 97, 54–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2019.02.004 (2019).

Wang, S. J., Lu, C. Y., Huang, S. H. & Wong, D. S. H. Reactive vapor-recompression distillation for green hexamethylene-1,6-dicarbamate synthesis. Chem. Eng. Process. Process. Intensif. 149, 107827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cep.2020.107827 (2020).

Zhang, X., Li, C., Fu, C. & Zhang, S. Environmental impact assessment of chemical process using the green degree method. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 47, 1085–1094. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie0705599 (2008).

Shi, S. et al. Energetic–Environmental–Economic assessment of integrated different carbon capture and compression processes for high CO2 concentration gas. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 11, 16840–16848. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.3c05757 (2023).

Li, H., Chang, L., Li, H., Li, Q. & Wang, Y. Whole-component anaerobic methanogenesis of pre-acidized sludge: optimal process and promotion mechanisms. Chem. Eng. Sci. 289, 119871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2024.119871 (2024).

Yan, R. et al. Green process for methacrolein separation with ionic liquids in the production of Methyl methacrylate. AIChE J. 57, 2388–2396. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.12449 (2011).

Yan, N. et al. Multi-objective optimization of biomass to biomethane system. Green. Energy Environ. 1, 156–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gee.2016.05.001 (2016).

Xu, Y., Huang, Y., Wu, B., Zhang, X. & Zhang, S. Biogas upgrading technologies: energetic analysis and environmental impact assessment. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 23, 247–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjche.2014.09.048 (2015).

Tian, X. et al. Process analysis and Multi-Objective optimization of ionic Liquid-Containing acetonitrile process to produce 1,3-Butadiene. Chem. Eng. Technol. 34, 927–936. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceat.201000426 (2011).

Li, W. et al. Multi-objective optimization of methane production system from biomass through anaerobic digestion. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 26, 2084–2092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjche.2018.01.001 (2018).

Pi, X. et al. Computer-aided ionic liquid design for green chemical processes based on molecular simulation and artificial intelligence. Sep. Purif. Technol. 361, 131585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2025.131585 (2025).

Serna-Jiménez, J. A., Torres-Valenzuela, L. S. & Mejía-Arango, G. Evaluation and comparison in caffeine extraction under green conditions: solvent selection and ultrasound-assisted process. J. Food Process. Eng. 45, e14157. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfpe.14157 (2022).

Deb, K., Pratap, A., Agarwal, S. & Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 6, 182–197. https://doi.org/10.1109/4235.996017 (2002).

Abualigah, L. et al. Aquila optimizer: A novel meta-heuristic optimization algorithm. Comput. Ind. Eng. 157, 107250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2021.107250 (2021).

Rangaiah, G. P., Feng, Z. & Hoadley, A. F. Multi-objective optimization applications in chemical process engineering: Tutorial and review. Processes https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9717/8/5/508 (2020).

Dai, M., Yang, F., Zhang, Z., Liu, G. & Feng, X. Energetic, economic and environmental (3E) multi-objective optimization of the back-end separation of ethylene plant based on adaptive surrogate model. J. Clean. Prod. 310, 127426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127426 (2021).

Keßler, T. et al. Global optimization of distillation columns using explicit and implicit surrogate models. Chem. Eng. Sci. 197, 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2018.12.002 (2019).

Wang, Z., Li, J., Rangaiah, G. P. & Wu, Z. Machine learning aided multi-objective optimization and multi-criteria decision making: framework and two applications in chemical engineering. Comput. Chem. Eng. 165, 107945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compchemeng.2022.107945 (2022).

Mnih, V. et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nat 518, 529–533. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14236 (2015).

Jordan, M. I. & Mitchell, T. M. Machine learning: trends, perspectives, and prospects. Sci 349, 255–260. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa8415 (2015).

Vavalle, A. & Qin, N. Iterative response surface based optimization scheme for transonic airfoil design. J. Aircr. 44, 365–376. https://doi.org/10.2514/1.19688 (2007).

Bernardini, E., Spence, S. M. J., Wei, D. & Kareem, A. Aerodynamic shape optimization of civil structures: A CFD-enabled Kriging-based approach. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 144, 154–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jweia.2015.03.011 (2015).

Yun, Y., Yoon, M. & Nakayama, H. Multi-objective optimization based on meta-modeling by using support vector regression. Optim. Eng. 10, 167–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11081-008-9063-1 (2009).

Qasem, S. N. & Shamsuddin, S. M. Radial basis function network based on time variant multi-objective particle swarm optimization for medical diseases diagnosis. Appl. Soft Comput. 11, 1427–1438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2010.04.014 (2011).

Wu, Y., Zhan, Q. & Quan, S. J. Improving local pedestrian-level wind environment based on probabilistic assessment using Gaussian process regression. Build. Environ. 205, 108172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108172 (2021).

Zhang, X., Xie, F., Ji, T., Zhu, Z. & Zheng, Y. Multi-fidelity deep neural network surrogate model for aerodynamic shape optimization. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 373, 113485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cma.2020.113485 (2021).

Azizi Oroumieh, M. A., Mohammad Bagher Malaek, S., Ashrafizaadeh, M., Mahmoud & Taheri Aircraft design cycle time reduction using artificial intelligence. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 26, 244–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ast.2012.05.003 (2013).

Bemani, A. et al. Modeling of cetane number of biodiesel from fatty acid Methyl ester (FAME) information using GA-, PSO-, and HGAPSO- LSSVM models. Renew. Energy. 150, 924–934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.12.086 (2020).

Nabipour, N. et al. Estimating biofuel density via a soft computing approach based on intermolecular interactions. Renew. Energy. 152, 1086–1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2020.01.140 (2020).

Hegab, H., Salem, A., Rahnamayan, S. & Kishawy, H. A. Analysis, modeling, and multi-objective optimization of machining inconel 718 with nano-additives based minimum quantity coolant. Appl. Soft Comput. 108, 107416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2021.107416 (2021).

Sana, M., Asad, M., Farooq, M. U., Anwar, S. & Talha, M. Sustainable electric discharge machining using alumina-mixed deionized water as dielectric: process modelling by artificial neural networks underpinning net-zero from industry. J. Clean. Prod. 441, 140926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.140926 (2024).

Chandana, K. S., Karka, S., Gujral, M. K., Kamesh, R. & Roy, A. Machine learning aided catalyst activity modelling and design for direct conversion of CO2 to lower olefins. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 109555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2023.109555 (2023).

Xu, M., Cao, L., Lu, D., Hu, Z. & Yue, Y. Application of swarm intelligence optimization algorithms in image processing: A comprehensive review of analysis, synthesis, and optimization. Biomimetics 8, 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics8020235 (2023).

Domingues, L., Pinheiro, C. I. C. & Oliveira, N. M. C. Optimal design of reactive distillation systems: application to the production of Ethyl tert-butyl ether (ETBE). Comput. Chem. Eng. 64, 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compchemeng.2014.01.014 (2014).

Rebello, C. M. & Nogueira, I. B. R. Optimizing CO2 capture in pressure swing adsorption units: A deep neural network approach with optimality evaluation and operating maps for decision-making. Sep. Purif. Technol. 340, 126811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2024.126811 (2024).

Tharakeshwar, T. K., Seetharamu, K. N. & Durga Prasad, B. Multi-objective optimization using Bat algorithm for shell and tube heat exchangers. Appl. Therm. Eng. 110, 1029–1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.09.031 (2017).

Zhao, F. et al. Batch-to-continuous process design and economic, energy, exergy, and environmental analyses of Claisen ester condensation based on diethyl 2-ethyl-2-phenylmalonate synthesis. J. Clean. Prod. 251, 119619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119619 (2020).

Ibrahim, M., Al-Sobhi, S., Mukherjee, R. & AlNouss, A. Impact of sampling technique on the performance of surrogate models generated with artificial neural network (ANN): A case study for a natural gas stabilization unit. Energies 12, 1906. https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/12/10/1906 (2019).

Zhu, J., Jiang, Z. & Feng, L. Improved neural network with least square support vector machine for wastewater treatment process. Chemosphere 308, 136116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136116 (2022).

Si, B. et al. Multi-objective optimization design of a complex Building based on an artificial neural network and performance evaluation of algorithms. Adv. Eng. Inf. 40, 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2019.03.006 (2019).

Yu, X. et al. Multi-objective optimization of ANN-based PSA model for hydrogen purification from steam-methane reforming gas. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 46, 11740–11755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.01.107 (2021).

Shahbaz, M. et al. Artificial neural network approach for the steam gasification of palm oil waste using bottom Ash and CaO. Renew. Energy. 132, 243–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2018.07.142 (2019).

Zhang, Z. et al. Multi-objective optimization of milk powder spray drying system considering environmental impact, economy and product quality. J. Clean. Prod. 369, 133353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133353 (2022).

Singh, N. K. et al. Artificial intelligence and machine learning-based monitoring and design of biological wastewater treatment systems. Bioresour Technol. 369, 128486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2022.128486 (2023).

Yang, X.-S. In Nature Inspired Cooperative Strategies for Optimization (NICSO 2010) (eds Juan R. González et al.) 65–74 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2010).

Wang, Y. et al. Optimal design of integrated energy system considering economics, autonomy and carbon emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 225, 563–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.03.025 (2019).

Lai, X. et al. Global parametric sensitivity analysis of equivalent circuit model based on Sobol’ method for lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles. J. Clean. Prod. 294, 126246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126246 (2021).

Wang, Y., He, X. & Jiang, F. The energy conservation and emission reduction potentials in China’s iron and steel industry: Considering the uncertainty factor. J. Clean. Prod. 413, 137519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137519 (2023).

Zhang, D., Zhang, H., Luo, Y., Zhao, S. & Miao, X. Exploring energetic, exergetic, economic and environmental (4E) performance of waste heat power generation in nuclear power plant systems: A perspective of pattern recognition. J. Clean. Prod. 425, 138911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138911 (2023).

You, C. X. et al. Energy-saving extractive distillation system using o-xylene as an entrainer for the high-purity separation of dimethyl carbonate/methanol azeotrope. Sep. Purif. Technol. 350, 127893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2024.127893 (2024).

Gu, X. et al. Technical-environmental assessment of CO2 conversion process to dimethyl carbonate/ethylene glycol. J. Clean. Prod. 288, 125598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125598 (2021).

Zhu, R., Gui, C., Li, G. & Lei, Z. Modified COSMO-UNIFAC model for ionic liquid–CO systems and molecular dynamic simulation. AIChE J. 68, e17724. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.17724 (2022).

Wei, H., Wang, F., Yan, H., Jiao, W. Z. & Wei, W. Atmospheric-pressurized process for dimethyl carbonate/methanol separation with and without heat integration: design and control. ACS Omega. 8, 20450–20470. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c00656 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC3905401) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62333010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.L. wrote the main manuscript text; G.Z. assisted in developing the software code; S.H. conducted the literature review; and Z.Z. secured funding and supervised the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, B., Zhang, G., Hong, S. et al. ANN assisted optimization of phosgene free hexamethylene diisocyanate production for economic and environmental benefits. Sci Rep 15, 33973 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11730-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11730-3