Abstract

This study was designed to develop and validate a risk-prediction nomogram to predict the incidence of prolonged disorders of consciousness (pDoC) in patients with severe supratentorial hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage (HICH). The clinical data of 222 severe supratentorial HICH patients who were admitted from January 2017 to June 2024 were reviewed, from which 155 patients were enrolled in the training group, while 67 were enrolled in the internal validation group, at a ratio of 7:3. The external data sets containing 197 patients were obtained from another hospital. Independent predictors of pDoC were analyzed using multivariate logistic regression. Furthermore, a nomogram prediction model was constructed using R software. After evaluation of the model, internal and external validations were performed to verify the efficiency of the model using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUC), calibration plots and decision curve analysis. In multivariate analysis, GCS score (p = 0.002), systolic blood pressure (p = 0.010), hematoma volume (p = 0.012), and modified Graeb Score (p = 0.014) were independent predictors for pDoC in patients with severe supratentorial HICH. The AUC for the training, internal, and external validation cohorts was 0.905 (95% CI: 0.853, 0.958), 0.857 (95% CI: 0.764, 0.950), and 0.897 (95% CI: 0.844, 0.950), respectively, which indicated that the prediction model had an excellent capability of discrimination. Calibration of the model was exhibited by the calibration plots, which showed an optimal concordance between the predicted pDoC probability and actual probability in both training and validation cohorts. Decision curve analysis curves suggested that the predictive model had high clinical utility in practical applications. A prediction model for predicting pDoC in severe supratentorial HICH patients was constructed. The model can help clinicians to identify high-risk patients as soon as possible and prevent the occurrence of pDoC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage (HICH) is one of the common diseases in neurosurgery, which refers to hemorrhage caused by the rupture of blood vessels in the brain parenchyma, with high rates of disability and mortality1. It accounts for approximately 17.1-55.4% of all strokes2. Currently, surgical treatment is one of the main treatments for HICH, which can reduce intracranial pressure and thus minimize the extent of damage to brain tissue3. In patients with severe HICH, even with surgical intervention, the prognosis for the majority of patients remains poor, including difficulty in recovering consciousness in the short term, followed by the development of prolonged disorders of consciousness (pDoC)4.

The pDoC represents an imbalance between the components of consciousness5which is one of the common complications in patients with severe ICH, with incidences ranging from 0.6 to 6.1 per 100,000 adults6. Moreover, it is commonly thought that the prevalence of patients with pDoC is progressively increasing worldwide. As reported in the literature, disruption in the default mode network, such as cortico-cortical and subcortico-cortical connections, may be the anatomical basis for the occurrence of pDoC7which is directly associated with longer hospital stays, higher healthcare costs, and mortality8,9. Therefore, to effectively intervene pDoC, identifying the risk factors early and establishing an efficient predictive model is important.

Recently, some research studies focused on the prognosis study of patients with HICH based on their clinical characteristics and radiological signs. A lower Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score10 and larger hematoma volume11 have been proven as independent risk factors for poor prognosis. Francoeur et al. found that elevated systolic blood pressure may be an independent risk factor for predicting poor 3-month prognosis in ICH patients12. The modified Graeb Score (mGS) is used as an indicator to assess the severity of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), and also has a high predictive value for the prognosis of ICH13. Stroke, which causes brain injury, induces multiple mechanisms, including cell excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, and inflammatory responses14,15. A lower GCS score and larger hematoma volume on admission can reflect the severity of injury in ICH patients. Hematoma volume involves an increase in pressure, resulting in mass effect, midline shift, and herniation16. In addition, it is also one of the main causes of secondary brain injury, as iron and heme from lysed erythrocytes create a highly oxidative and cytotoxic environment, damaging brain tissue17,18. These all lead to significant neurological deficits after ICH. The presence of intraventricular blood has been strongly associated with poor outcomes including coma, mortality and long-term functional impairment, the reason for this is that prolonged exposure of the ventricles to blood may lead to altered consciousness and, at the tissue level, inflammation, fibrosis, and hydrocephalus19,20. Although these clinical factors are important, they have limited sensitivity and accuracy in predicting the outcomes of ICH alone. A nomogram is a visualization tool that integrates indicators from different dimensions, to predict the risk of disease occurrence in a graphical and individualized manner21. Based on these factors, numerous prediction models have been developed to predict the short-term prognosis of patients with HICH22,23. However, there is a lack of in-depth research exploring the risk factors associated with pDoC in HICH patients and evaluating the prediction models containing such factors. Therefore, this study aimed to construct a predictive model by assessing the risk factors for pDoC. We then converted the model formula into a nomogram that can be used by neurosurgeons for rapid clinical assessment of the risk of pDoC following HICH.

Methods

Ethics approval

The study was conducted in compliance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethics Committees of the Fuyang Fifth People’s Hospital (Ethics approval number: NO.2021002), and all procedures adhered to pertinent guidelines and regulations.

Study population

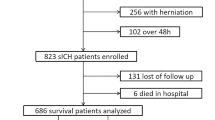

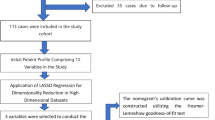

We collected the clinical medical records of 222 severe supratentorial HICH patients admitted to the Department of Neurosurgery, Fuyang Fifth People’s Hospital from January 2017 to June 2024. Later, the dataset was randomly partitioned into the training (155 patients) and internal validation (67 patients) groups in a ratio of 7:3. Inclusion criteria included: (1) age ≥ 18 years, with a history of hypertension or a diagnosis of hypertension during this hospitalization. (2) preoperative GCS score of 3–8. (3) supratentorial HICH within 6 h confirmed by computed tomography (CT). (4) all patients with supratentorial HICH underwent surgical treatment within 24 h following admission, including hematoma evacuation, hematoma puncture drainage, decompressive craniectomy, and external ventricular drainage (EVD). (5) patients had complete documentation. Exclusion criteria included: (1) ICH caused by head trauma, cerebral aneurysm, vascular malformation, and brain tumor. (2) primary intraventricular hemorrhage. (3) survival time after onset < 28 days. (4) long-term use of antiplatelet or anticoagulant drugs. (5) missing imaging data. (6) previous history of ICH or other neurological diseases such as ischemic stroke. (7) other systematic diseases such as severe hepatic and renal dysfunction, cancer, and hematological disorders; and (8) refusal to follow-up for clinical assessment.

Data collection

The clinical data including gender, age, time from symptom onset to baseline CT scan, history of diabetes and/or coronary heart disease, GCS score at admission, blood pressure at admission (systolic and diastolic blood pressure), location of hemorrhage (basal ganglia and thalamus), hematoma volume, mGS, cerebral hernia, and operative methods (including decompressive craniectomy, EVD, hematoma evacuation, hematoma evacuation combined with EVD, hematoma puncture drainage, hematoma puncture and drainage combined with EVD). The postoperative findings including rebleeding and intracranial infection were investigated.

Hematoma volumes were calculated by the ABC/2 method24. The mGS was calculated based on three factors, namely, location of intraventricular hemorrhage, hematoma volume in each ventricle, and ventricular dilatation, with a total score of 32 points25. To reduce subjective judgment errors, three experienced neurosurgeons independently scored the patients, and the average score was calculated.

All patients underwent CT preoperatively and at least two times postoperatively: immediately after surgery and at 1–3 days after surgery. Postoperative rebleeding was defined as postoperative hematoma volume greater than preoperative volume or postoperative hematoma volume less than preoperative volume, but the difference is less than 5 mL, or postoperative hematoma volume gradually increasing by 10 mL26,27. The diagnosis of intracranial infection defined according to the standards issued by the National Ministry of Health is as follows: (1) presence of clinical manifestation of intracranial infection, including temperature higher than 38 °C or lower than 36 °C, positive signs of meningeal irritation (nuchal rigidity, Brudzinski sign, and Kernig sign), vomiting, and headache. (2) positive changes in cerebrospinal fluid specimens: white blood cell count > 1,000 × 106 cells/L; glucose levels < 2.25 mmol/L; chloride < 120 mmol/L, and protein > 0.45 g/L; and (3) positive results for bacteria in cerebrospinal fluid culture28.

Definition of pDoC

pDoC refers to coma lasted for more than 28 days29. Accordingly, patients were divided into two groups: the pDoC group and the non-pDoC group.

Level of consciousness was classified weekly by expert staff members using the Coma Recovery Scale-Revised30. The Coma Recovery Scale-Revised is a bedside assessment tool for differentiating levels of consciousness (UWS, MCS-, MCS + and e-MCS) by observation of reactions to various stimuli. It is composed of 6 hierarchical subscales (auditory, visual, motor, oromotor/verbal, communication, and arousal function) with 23 dichotomously scored items. Total Coma Recovery Scale-Revised score ranges from 0 (comatose state) to 23 (e-MCS)31.

Outcome assessment

Patient outcome was evaluated by the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score at 3 months following HICH. Good outcomes were defined as GOS scores of 4–5, and a score of 1–3 was deemed a poor outcome32.

Development and validation of the prediction model

The data from the training cohort were used to perform univariate and multivariate analyses to identify the independent predictive factors for pDoC. The variance inflation factor (VIF) was analyzed in the regression model for the detection of multicollinearity with a VIF value of 5 or more referring to multicollinearity33. The nomogram was constructed based on multivariable logistic regression results. The performance of the nomogram was assessed by discrimination and calibration. Then, the internal validation cohorts were used to validate the nomogram in terms of discrimination, calibration, and clinical utility. The discriminative ability of the nomogram was evaluated using area under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUC), a perfect model would have an AUC of 134. The sensitivity and specificity analyses were performed by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. The calibration was evaluated using calibration curves and Hosmer-Lemeshow tests35. Both discrimination and calibration were evaluated using bootstrapping methods with 1000 resamples. Furthermore, decision curve analysis (DCA) was used to evaluate the net benefit of the model for patients36. Finally, the prediction model was validated externally in a separate external validation cohort. The external cohort data sets were obtained from the Department of Neurosurgery of Linquan County People’s Hospital (Fuyang, China) by using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria from January 2021 to January 2024. The performance of model was assessed using the AUC, calibration plots, and DCA. All models were validated through cross-validation to ensure robustness and generalizability.

Statistical analysis

Like in many retrospective studies, the presence of missing data is common. In the current study, the proportions of variables with missing data were postoperative rebleeding and intracranial infection were 5.3% and 3.7%, respectively. Instead of performing complete case analyses, multiple imputation was used to handle the missing data37,38.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 software (SPSS, INC; Chicago, USA), and nomogram establishment was undertaken by R 3.5.1 programming language (https://www.r-project.org). Categorical variables were presented as numbers with percentages. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range). Group comparisons were conducted using t tests for normally-distributed quantitative variables, the Mann-Whitney U tests for non-normally distributed quantitative variables and the Pearson chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables where appropriate. All statistical tests were two-sided, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Participant characteristics

In total, 419 severe supratentorial HICH patients who met the inclusion criteria were included in this study. There were 114 (27.2%) patients who developed pDoC. Out of the 155 patients in the training group, 55 (35.5%) were diagnosed with pDoC, while 21 (31.3%) out of the 67 patients in the internal validation group were diagnosed with pDoC, and 38 (19.3%) out of the 197 patients in the external validation group were diagnosed with pDoC. Table 1 summarizes patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and surgical and laboratory data for the training, internal validation, and external validation cohorts.

Construction of the predictive nomogram

Table 2 presents the baseline characteristics of patients with and without pDoC in the training cohort. The pDoC group showed lower initial GCS and higher rate of women than the non-pDoC group. Compared with non-pDoC patients, patients with pDoC had higher levels of systolic blood pressure, hematoma volume, and mGS. In addition, pDoC patients had more incidence of cerebral hernia and decompressive craniectomy. There were also significant differences in operative methods between the groups. Then, a multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to screen for significant predictors of the development of pDoC in severe supratentorial HICH patients. Multicollinearity was not observed between the independent variables studied and pDoC. The results revealed that GCS score (odds ratio [OR], 0.436; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.259–0.735; p = 0.002), systolic blood pressure (OR, 1.026; 95% CI, 1.006–1.046; p = 0.010), hematoma volume (OR, 1.046; 95% CI, 1.010–1.083; p = 0.012), and mGS (OR, 1.221; 95% CI, 1.041–1.432; p = 0.014) were independent predictors for pDoC in patients with severe supratentorial HICH (Table 3). Based on the four independent predictors of pDoC identified by multivariate logistic regression modeling, we constructed the nomogram for pDoC in severe supratentorial HICH patients (Fig. 1). The regression equation for the model is: Logit (P) = −5.124–0.829*GCS score + 0.025*systolic blood pressure + 0.045*hematoma volume + 0.199*mGS.

Scoring system for pDoC

The scoring system of pDoC was established based on the multiple factors logistic regression analysis. A scoring system was developed according to the parameters and coefficients in the formula. The coefficient of each variable in the formula was transformed to corresponding score for the point assignment in scoring system. In the scoring system, each systolic blood pressure, GCS score, hematoma volume, and mGS value has a specific corresponding point, and points of the four were added to obtain the total score. The corresponding risk of the total score was the probability of pDoC occurrence. For example, if the total point was 150, the probability of pDoC was predicted to be 0.8, that is, 80% (Table 4).

Here, we cite an example to show how to use the nomogram, assuming that the patient with ICH has a GCS score of 5, an mGS of 9, a hematoma volume of 85mL, and his systolic blood pressure is 202mmHg. As can be seen in Fig. 1, to obtain the “point” axis for each parameter corresponding to the score. The final score was calculated for all parameters (40 (GCS) + 20 (mGS) + 60 (hematoma volume) + 30 (systolic blood pressure) = 150). This score corresponds to a risk of approximately 80% of developing pDoC.

Validation of the predictive nomogram

In the training, internal validation, and external validation cohorts, the AUC under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.905 (95% CI: 0.853, 0.958), 0.857 (95% CI: 0.764, 0.950), and 0.897 (95% CI: 0.844, 0.950), respectively (Fig. 2; Table 5), which indicated that the nomogram had a good discriminative ability. The p value of the Hosmer-Lemeshow test was 0.710 in the training set, 0.892 in the internal validation set and 0.651 in the external validation set, respectively. The calibration ability of the model is exhibited with bootstrap-corrected calibration plots (Fig. 3), which show an optimal concordance between the predicted and actual probabilities of pDoC in both the training and validation cohorts. Finally, the DCA curves also suggested that the predictive model had high clinical utility in practical applications (Fig. 4).

Decision curve analysis for predicting the risk of prolonged disorders of consciousness in patients with severe supratentorial hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage by the nomogram model. The threshold probability range of the training set was 4–80% (A), the threshold probability range of the internal validation cohort was 3–80% (B), the threshold probability range of the external validation cohort was 3–62% (C).

Discussion

Prolonged disorders of consciousness was reported in quite a large proportion of patients with severe HICH, and it is associated mainly with unfavorable outcomes. In order to identify and prevent the occurrence of pDoC as early as possible, it is important and urgent to explore predictors of pDoC. This study found that the four variables collected at admission (GCS score, systolic blood pressure, hematoma volume, and mGS) were significantly related to pDoC, based on the logistic regression analysis. To our best knowledge, this is the first study to develop a nomogram for evaluating the risk of pDoC in patients with severe HICH.

The GCS score is the simplest and most reliable method to evaluate the severity and prognosis of patients with ICH39. Various studies have shown that a lower GCS indicates poor prognosis, and GCS has been found to be an indispensable predictor in various model studies40,41. The results of the present study showed that a lower GCS score was an independent risk factor for the occurrence of pDoC in patients with severe HICH, which is consistent with previous reports11. Nagesh et al. reported that in patients with lower GCS scores, repeat CT scans could exhibit abnormalities during hospitalization42. Besides, a lower GCS score was found to be associated with an increased risk of hematoma expansion43which is a major cause of neurological deterioration. Thus, it is evident that patients with severe HICH who have lower GCS scores are prone to develop pDoC.

Patients with HICH frequently present with an elevation in blood pressure on admission, which on the one hand reflects the degree of preexisting hypertension, and on the other hand is related to the cerebrovascular autoregulation mechanism that maintains constant cerebral blood flow. Recently, some scholars have reported that blood pressure is an important factor influencing the prognosis of ICH, with elevated blood pressure being linked to hematoma expansion, neurological deterioration, and unfavorable outcomes44. Francoeur et al. demonstrated that systolic blood pressure can be served as a significant predictor of poor prognosis12. Nishikawa et al. showed that systolic blood pressure on admission was an independent risk factor for hematoma expansion in HICH patients45. A retrospective study on systolic blood pressure and DoC in patients with ICH revealed that elevated systolic blood pressure was an independent predictor of DoC46. The findings of this study indicated that higher systolic blood pressure at admission was an independent risk factor for postoperative pDoC in patients with severe HICH, suggesting that the higher systolic blood pressure of the patient, the greater likelihood of pDoC. Therefore, patients with severe HICH who present with high systolic blood pressure should be monitored closely for any fluctuations in blood pressure during hospitalization, and appropriate clinical interventions should be employed to enhance patient prognosis.

Hematoma volume, size, and diameter on admission has often been shown to significantly correlate with short term mortality47,48,49. ICH volume is widely suggested as the most important predictor of outcomes in ICH50. Previous studies have also investigated the relationship between CT signs and consciousness level. Xiong et al. demonstrated that reductions in cerebral blood flow and cerebral blood volume calculated with perfusion CT were associated with impaired consciousness51. Liu et al. found in their studies of ICH that hemorrhage volume was strongly correlated with DoC as a predictive risk factor, and this CT sign is more direct and objective than the DoC assessment based on patient behavior52. The current study revealed a significant correlation between hematoma volume and pDoC in patients with severe HICH. This may be attributed to the mechanical damage from the excessive hemorrhage, while a larger hematoma volume contributes to secondary brain injury, as iron and heme from lysed erythrocytes create a highly oxidative and cytotoxic environment, damaging brain tissue53. The combined effect of both can significantly impede the restoration of neurological function following HICH, potentially leading to the occurrence of pDoC.

Intraventricular hemorrhage extension of ICH is independently associated with unfavorable outcome54,55. Factors that are thought to mediate the worsening effect on outcome are meningitis, induced by blood breakdown products, development of hydrocephalus, and the excess intracranial volume itself leading to increased intracranial pressure56,57. Previous studies have found that the volume of IVH is a reliable predictor of the prognosis of ICH, and is also effective in predicting the risk of pDoC after ICH58. Witsch et al. found that loss of consciousness at ictus was associated with greater amounts of intraventricular hemorrhage in patients with ICH59. mGS is a commonly used index for evaluating the extension of IVH, and our nomogram model clearly showed that mGS contributed significantly to pDoC prediction, indicating a strong correlation between pDoC and the severity of IVH, which we believe may also contribute to the superior performance of our predictive model for all evaluated indicators. In addition, IVH was found to be associated with hematoma expansion, which subsequently triggered secondary brain injury after ICH13. Evidently, a higher IVH grade exacerbates the risk of developing pDoC.

Early detection is a key to preventing the occurrence of pDoC. This is best accomplished by identifying high-risk patients. Consequently, these patients need to be under observation, followed up, and should undergo early intervention. The nomogram is one of the methods to present the predicted model as the graphic scoring. After performing the multivariate regression analysis, we included GCS score, systolic blood pressure, hematoma volume, and mGS, a total of four factors, as nomogram score points. During the plotting process, each clinical predictor was assigned with a distinct score, and the cumulative score was calculated and then used to estimate the probability of pDoC occurrence in the patients, which has high predictive capability and can be used as a reliable predictive tool for clinicians to identify high-risk populations. The nomogram prediction model had good discrimination and clinical utility. The AUC for predicting the risk of pDoC in the training set was 0.905, and also reached 0.857 in the validation group. The calibration plot almost perfectly fit the actual situation. DCA analysis showed that the nomogram exhibited excellent clinical applicability in predicting the risk of pDoC, and the prediction model also performed well in the goodness-of-fit test. The above indicates that the nomogram prediction model may play a positive role in predicting the risk of pDoC in patients with severe HICH. Compared with traditional clinical prediction methods, the nomogram model can more intuitively show the relationship between various risk factors and prognosis, providing a quantitative prediction tool for clinicians60. In addition, the model helps to improve the accuracy of prediction and provides the basis for patients to develop individual treatment plans. In patients with severe HICH, targeted treatment measures can be formulated according to the relevant risk factors to adjust the treatment regimen, thereby effectively improving the prognosis of the patient.

However, this study has several limitations. First, this study used a retrospective analysis, and the underlying bias could not be avoided. In order to reduce data collection bias, we ensure the reliability and accuracy of the data sources, rigorously check the integrity of the data, and use appropriate statistical methods to handle missing and outlier values. Second, the sample size of this study is not very large, although we have made every effort to ensure sample diversity and representativeness, and adopted appropriate methods in statistical analysis to reduce bias, the small sample size may still limit the generalizability and robustness of the research results. Third, although multicenter data was used in this study, the data came from a single hospital and one collaborating institution, which may introduce regional or institutional bias, affecting the generalizability of the model. Additional unmentioned limitations include potential confounders that were not fully controlled for, such as age and comorbidities, which may affect the validity of the findings. It is necessary to conduct large sample and multicenter prospective studies to prove the feasibility of the nomogram and increase the possibility of extensive popularization of the model.

Conclusion

Studies have shown that GCS score, systolic blood pressure, hematoma volume, and mGS are predictive factors for the development of pDoC in severe supratentorial HICH patients. We developed a predictive model based on a multifactorial logistic regression model using these factors for predicting the risk of pDoC. By utilizing the established pDoC risk prediction model from this study, clinical health care professionals may efficiently identify high-risk groups for pDoC and prioritize early interventions for these high-risk individuals. The predictive model may have practical implications for improving patient outcomes and guiding clinical decision-making in the management of severe HICH patients.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HICH:

-

hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage

- pDoC:

-

prolonged disorders of consciousness

- GCS:

-

Glasgow coma scale

- mGS:

-

modified Graeb Score

- IVH:

-

intraventricular hemorrhage

- CT:

-

computed tomography

- EVD:

-

external ventricular drainage

- GOS:

-

Glasgow Outcome Scale

- VIF:

-

variance inflation factor

- AUC:

-

area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- ROC:

-

receiver operating characteristic

- DCA:

-

decision curve analysis

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- CI:

-

confidence interval

References

Hostettler, I. C., Seiffge, D. J. & Werring, D. J. Intracerebral hemorrhage: an update on diagnosis and treatment. Expert Rev. Neurother. 19, 679–694. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2019.1623671 (2019).

Ziai, W. C. & Carhuapoma, J. R. Intracerebral hemorrhage. Continuum (Minneapolis Minn). 24, 1603–1622. https://doi.org/10.1212/con.0000000000000672 (2018).

Schrag, M. & Kirshner, H. Management of intracerebral hemorrhage: JACC focus seminar. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 75, 1819–1831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.10.066 (2020).

Vergara, F. Prolonged disorders of consciousness after an acute brain injury]. Rev. Med. Chil. 147, 1621–1625. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0034-98872019001201621 (2019).

Laureys, S. The neural correlate of (un)awareness: lessons from the vegetative state. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9, 556–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2005.10.010 (2005).

van Erp, W. S. et al. The vegetative state/unresponsive wakefulness syndrome: a systematic review of prevalence studies. Eur. J. Neurol. 21, 1361–1368. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.12483 (2014).

Lant, N. D., Gonzalez-Lara, L. E., Owen, A. M. & Fernández-Espejo, D. Relationship between the anterior forebrain mesocircuit and the default mode network in the structural bases of disorders of consciousness. NeuroImage Clin. 10, 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2015.11.004 (2016).

Monti, M. M., Laureys, S. & Owen, A. M. The vegetative state. BMJ (Clinical Res. ed.). 341, c3765. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c3765 (2010).

Carlson, J. M. & Lin, D. J. Prognostication in prolonged and chronic disorders of consciousness. Semin. Neurol. 43, 744–757. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1775792 (2023).

Stein, M. et al. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage with ventricular extension and the grading of obstructive hydrocephalus: the prediction of outcome of a special life-threatening entity. Neurosurgery 67, 1243–1251. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0b013e3181ef25de (2010). discussion 1252.

Øie, L. R. et al. Functional outcome and survival following spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: A retrospective population-based study. Brain Behav. 8, e01113. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1113 (2018).

Francoeur, C. L. & Mayer, S. A. Acute blood pressure and outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage: the VISTA-ICH cohort. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Diseases: Official J. Natl. Stroke Association. 30, 105456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105456 (2021).

Wang, S. et al. Combining modified Graeb score and intracerebral hemorrhage score to predict poor outcome in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage undergoing surgical treatment. Front. Neurol. 13, 915370. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.915370 (2022).

Wu, J. et al. Oxidative brain injury from extravasated erythrocytes after intracerebral hemorrhage. Brain Res. 953, 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03268-7 (2002).

Alsbrook, D. L. et al. Neuroinflammation in acute ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 23, 407–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-023-01282-2 (2023).

LoPresti, M. A. et al. Hematoma volume as the major determinant of outcomes after intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Neurol. Sci. 345, 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2014.06.057 (2014).

Aronowski, J. & Zhao, X. Molecular pathophysiology of cerebral hemorrhage: secondary brain injury. Stroke 42, 1781–1786. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.110.596718 (2011).

Xiong, X. Y., Wang, J., Qian, Z. M. & Yang, Q. W. Iron and intracerebral hemorrhage: from mechanism to translation. Translational Stroke Res. 5, 429–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-013-0317-7 (2014).

Hanley, D. F. Intraventricular hemorrhage: severity factor and treatment target in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 40, 1533–1538. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.108.535419 (2009).

Pang, D., Sclabassi, R. J. & Horton, J. A. Lysis of intraventricular blood clot with urokinase in a canine model: part 3. Effects of intraventricular urokinase on clot Lysis and posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 19, 553–572. https://doi.org/10.1227/00006123-198610000-00010 (1986).

Grimes, D. A. The nomogram epidemic: resurgence of a medical relic. Ann. Intern. Med. 149, 273–275. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-149-4-200808190-00010 (2008).

Liu, M. et al. Predictive Nomogram for Unfavorable Outcome of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage. World neurosurgery 164, e1111-e1122, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2022.05.111

Zou, J. et al. Development and validation of a nomogram to predict the 30-day mortality risk of patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Front. NeuroSci. 16 https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.942100 (2022).

Kothari, R. U. et al. The ABCs of measuring intracerebral hemorrhage volumes. Stroke 27, 1304–1305. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.27.8.1304 (1996).

Morgan, T. C. et al. The modified Graeb score: an enhanced tool for intraventricular hemorrhage measurement and prediction of functional outcome. Stroke 44, 635–641. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.112.670653 (2013).

Song, P. et al. Post-operative rebleeding in patients with spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage: factors and clinical outcomes. Am. J. Translational Res. 15, 5168–5183 (2023).

Ren, Y., Zheng, J., Liu, X., Li, H. & You, C. Risk factors of rehemorrhage in postoperative patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: A Case-Control study. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 61, 35–41. https://doi.org/10.3340/jkns.2017.0199 (2018).

Yu, Y. & Li, H. J. Diagnostic and prognostic value of procalcitonin for early intracranial infection after craniotomy. Brazilian J. Med. Biol. Res. = Revista Brasileira De Pesquisas Medicas E Biologicas. 50, e6021. https://doi.org/10.1590/1414-431x20176021 (2017).

Kondziella, D. et al. European academy of neurology guideline on the diagnosis of coma and other disorders of consciousness. Eur. J. Neurol. 27, 741–756. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14151 (2020).

Giacino, J. T., Kalmar, K. & Whyte, J. The JFK coma recovery Scale-Revised: measurement characteristics and diagnostic utility. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 85, 2020–2029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2004.02.033 (2004).

Driessen, D. M. F., Utens, C. M. A., Ribbers, P. G. M., van Erp, W. S. & Heijenbrok-Kal, M. H. Short-term outcomes of early intensive neurorehabilitation for prolonged disorders of consciousness: A prospective cohort study. Annals Phys. Rehabilitation Med. 67 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2024.101838 (2024).

Wilson, J. T., Pettigrew, L. E. & Teasdale, G. M. Structured interviews for the Glasgow outcome scale and the extended Glasgow outcome scale: guidelines for their use. J. Neurotrauma. 15, 573–585. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.1998.15.573 (1998).

Marcoulides, K. M. & Raykov, T. Evaluation of variance inflation factors in regression models using latent variable modeling methods. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 79, 874–882. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164418817803 (2019).

Harrell, F. E. Jr., Califf, R. M., Pryor, D. B., Lee, K. L. & Rosati, R. A. Evaluating the yield of medical tests. Jama 247, 2543–2546 (1982).

Kramer, A. A. & Zimmerman, J. E. Assessing the calibration of mortality benchmarks in critical care: the Hosmer-Lemeshow test revisited. Crit. Care Med. 35, 2052–2056. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.Ccm.0000275267.64078.B0 (2007).

Vickers, A. J. & Holland, F. Decision curve analysis to evaluate the clinical benefit of prediction models. Spine Journal: Official J. North. Am. Spine Soc. 21, 1643–1648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2021.02.024 (2021).

Blazek, K., van Zwieten, A., Saglimbene, V. & Teixeira-Pinto, A. A practical guide to multiple imputation of missing data in nephrology. Kidney Int. 99, 68–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.07.035 (2021).

Beesley, L. J. et al. Multiple imputation with missing data indicators. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 30, 2685–2700. https://doi.org/10.1177/09622802211047346 (2021).

Widyadharma, I. P. E. et al. Modified ICH score was superior to original ICH score for assessment of 30-day mortality and good outcome of non-traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 209, 106913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2021.106913 (2021).

Koehl, K. E., Panos, N. G., Peksa, G. D. & Slocum, G. W. Clinical outcomes after 4F-PCC for warfarin-associated ICH and baseline GCS less than or equal to 8. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 59, 59–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2022.06.041 (2022).

Feng, H., Wang, X., Wang, W. & Zhao, X. Risk factors and a prediction model for the prognosis of intracerebral hemorrhage using cerebral microhemorrhage and clinical factors. Front. Neurol. 14, 1268627. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1268627 (2023).

Nagesh, M. et al. Role of repeat CT in mild to moderate head injury: an institutional study. NeuroSurg. Focus. 47, E2. https://doi.org/10.3171/2019.8.Focus19527 (2019).

Yaghi, S. et al. Hematoma expansion in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: predictors and outcome. Int. J. Neurosci. 124, 890–893. https://doi.org/10.3109/00207454.2014.887716 (2014).

Roh, D. et al. Primary intracerebral hemorrhage: A closer look at hypertension and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurocrit. Care. 29, 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-018-0514-z (2018).

Nishikawa, T. et al. Preventive effect of aggressive blood pressure Lowering on hematoma enlargement in patients with ultra-acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurol. Med. Chir. 50, 966–971. https://doi.org/10.2176/nmc.50.966 (2010).

Irisawa, T. et al. An association between systolic blood pressure and stroke among patients with impaired consciousness in out-of-hospital emergency settings. BMC Emerg. Med. 13 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-227x-13-24 (2013).

Broderick, J. P., Brott, T. G., Duldner, J. E., Tomsick, T. & Huster, G. Volume of intracerebral hemorrhage. A powerful and easy-to-use predictor of 30-day mortality. Stroke 24, 987–993. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.24.7.987 (1993).

Zubkov, A. Y. et al. Predictors of outcome in warfarin-related intracerebral hemorrhage. Arch. Neurol. 65, 1320–1325. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.65.10.1320 (2008).

Kim, K. H. Predictors of 30-day mortality and 90-day functional recovery after primary intracerebral hemorrhage: hospital based multivariate analysis in 585 patients. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 45, 341–349. https://doi.org/10.3340/jkns.2009.45.6.341 (2009).

Daverat, P., Castel, J. P., Dartigues, J. F. & Orgogozo, J. M. Death and functional outcome after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. A prospective study of 166 cases using multivariate analysis. Stroke 22, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.22.1.1 (1991).

Xiong, Q. et al. Relationship between consciousness level and perfusion computed tomography in patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness. Aging 14, 9668–9678. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.204417 (2022).

Liu, G. et al. The signs of computer tomography combined with artificial intelligence can indicate the correlation between status of consciousness and primary brainstem hemorrhage of patients. Front. Neurol. 14 https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1116382 (2023).

Chen, S., Yang, Q., Chen, G. & Zhang, J. H. An update on inflammation in the acute phase of intracerebral hemorrhage. Translational Stroke Res. 6, 4–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-014-0384-4 (2015).

Maas, M. B. et al. Delayed intraventricular hemorrhage is common and worsens outcomes in intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology 80, 1295–1299. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828ab2a7 (2013).

Witsch, J. et al. Intraventricular hemorrhage expansion in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology 84, 989–994. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000001344 (2015).

Phan, T. G., Koh, M., Vierkant, R. A. & Wijdicks, E. F. Hydrocephalus is a determinant of early mortality in putaminal hemorrhage. Stroke 31, 2157–2162. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.31.9.2157 (2000).

Cordonnier, C., Demchuk, A., Ziai, W. & Anderson, C. S. Intracerebral haemorrhage: current approaches to acute management. Lancet (London England). 392, 1257–1268. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31878-6 (2018).

Bisson, D. A. et al. Original and modified Graeb score correlation with intraventricular hemorrhage and clinical outcome prediction in hyperacute intracranial hemorrhage. Stroke 51, 1696–1702. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.120.029040 (2020).

Witsch, J. et al. Intracerebral hemorrhage with intraventricular extension associated with loss of consciousness at symptom onset. Neurocrit. Care. 35, 418–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-020-01180-2 (2021).

Balachandran, V. P., Gonen, M., Smith, J. J. & DeMatteo, R. P. Nomograms in oncology: more than Meets the eye. Lancet Oncol. 16, e173–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(14)71116-7 (2015).

Funding

Research Project of the Health Commission of Fuyang City, Anhui Province (FY2021-081, FY2023-019), Horizontal Medical Project of Fuyang Normal University (2024FYNUEY05).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception or design of the work: Shen Wang, Hongtao Sun. Data collection: Ruhai Wang, Xianwang Li. Data analysis and interpretation: Shen Wang, Ruhai Wang. Drafting the article: Shen Wang. Critical revision of the article: Hongtao Sun. Other (study supervision, fundings, materials, etc.): Haicheng Hu, Hongtao Sun. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical requirements

This study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Fuyang Fifth People’s Hospital.

Informed consent

Since this is a retrospective study, the Ethics Committee of the Fuyang Fifth People’s Hospital waived the need for informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, S., Wang, R., Li, X. et al. A novel nomogram for predicting prolonged disorders of consciousness in severe supratentorial hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage patients. Sci Rep 15, 25911 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11798-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11798-x