Abstract

The increasing prevalence of anemia and cognitive decline among middle-aged and older adults poses significant public health challenges. While most studies have examined the impact of anemia on cognition, the potential for a bidirectional relationship, where cognitive function also influences anemia risk, remains less explored, particularly via longitudinal designs and advanced modeling. Therefore, we utilized data from 4521 participants (women = 2434, men = 2087) from the initial (2011–2012) and subsequent (2015–2016) waves of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). We measured hemoglobin levels, global cognitive function, and other factors. Linear regression was used to analyze the association between baseline anemia status and follow-up cognitive function in participants free from low cognitive performance at baseline. Binary logistic regression was used to examine the relationship between baseline cognitive function and the risk of having anemia at follow-up in participants without anemia at baseline. Finally, a cross-lagged panel model (CLPM) was used to evaluate the longitudinal bidirectional association between anemia status and cognition. Baseline anemia status was significantly associated with lower follow-up cognitive scores, particularly among women (estimates, 95% confidence interval, − 0.83 (− 1.39, − 0.28)). Higher baseline cognitive function was associated with a lower risk of follow-up anemia among women (OR = 0.97, 95% CI (0.94–0.99)) but not among men (OR = 0.02, 95% CI (0.98–1.06)). The CLPM results confirmed a robust bidirectional relationship: baseline anemia status predicted lower follow-up cognition (β = − 0.04), and lower baseline cognition predicted a greater risk of having anemia at follow-up (β = − 0.02). The standardized effect size of baseline anemia status on follow-up cognitive function was greater than that of baseline cognitive function on follow-up anemia status (− 0.04 vs. − 0.02). These findings provide strong evidence for a bidirectional longitudinal association between anemia status and cognitive function in this population, suggesting that interventions targeting either condition may yield reciprocal benefits for healthy aging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Instruction

Compared with the 2010 census, the Seventh National Population Census in China revealed a significant increase in the elderly population1. Aging is closely linked to the development of cognitive impairment and dementia, with the risk of developing these conditions increasing significantly after individuals reach the age of 652,3. Consequently, many studies have been conducted to pinpoint modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia, with the aim of facilitating successful aging.

Anemia, which is characterized by hemoglobin levels below 13 g/dL in men and 12 g/dL in women, is a prevalent and modifiable condition among older adults that affects approximately 10% of this population4. Many studies have established anemia as a contributor to diminished cognition, cognitive decline, and the development of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia5,6,7,8. Despite inconsistencies in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies9,10,11, systematic reviews have consistently endorsed this link, suggesting a unidirectional progression from anemia to cognitive impairment in subsequent assessments12,13,14. The proposed mechanism involves inadequate cerebral oxygen supply and cerebral hypoxia, which are indicative of compromised cerebral perfusion and neurological dysfunction15,16.

Importantly, prior meta-analyses have suggested the potential for reverse causality between cognitive decline and anemia. Cognitive decline is often linked with brain atrophy, which impacts areas of the brain that regulate appetite and eating behaviors, potentially resulting in reduced appetite and malnutrition17. Furthermore, those experiencing cognitive decline may struggle with tasks such as shopping, food storage, and preparation, leading to nutritional imbalances and heightened risks of malnutrition or anemia. A recent Japanese prospective study indicated that individuals with lower cognitive function, particularly older women, face an increased risk of developing anemia within three years18. However, existing longitudinal studies have predominantly explored unidirectional effects, examining either the influence of anemia on cognitive function or vice versa, without conclusively establishing a definitive bidirectional relationship.

While the potential for a bidirectional association exists, understanding this complex interplay in the Chinese context is particularly crucial due to several unique characteristics of the Chinese middle-aged and older population. First, this demographic exhibits a notable prevalence of both anemia and malnutrition; for example, a study based on CHARLS data reported an anemia prevalence of 20.6% among adults aged 60 years and above, with higher rates in disadvantaged groups19. Furthermore, nearly half of community-dwelling elderly individuals in China are at high risk of malnutrition. These high rates, potentially linked to nutritional and socioeconomic factors, may uniquely influence the anemia–cognition relationship20,21,22. Second, older cohorts in China often have lower average educational attainment than those in many Western countries do, potentially resulting in a lower cognitive reserve and increased vulnerability to cognitive impairment when faced with conditions such as anemia23. Third, following population aging in China, dramatic changes have been observed in the spectrum of diseases among Chinese residents24. The incidence and prevalence of chronic diseases (such as cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, metabolic, and respiratory diseases), which frequently coexist with anemia and cognitive decline, are constantly increasing19. The complex interplay of these factors—a high prevalence of anemia and malnutrition, a lower cognitive reserve, and prevalent chronic comorbidities—suggests that the bidirectional association between anemia and cognitive decline in the Chinese context may differ from that observed in other populations.

Given this unique demographic and epidemiological landscape and building on previous research exploring unidirectional links, this study aims to investigate the longitudinal bidirectional association between anemia status and cognitive decline among middle-aged and older Chinese adults via data from CHARLS. While our study design does not allow for a direct investigation of the underlying mechanisms, the literature suggests potential pathways such as impaired cerebral oxygenation and the critical role of iron in brain function25. Our findings contribute valuable evidence from a large, representative Chinese cohort, and this evidence is essential for understanding this relationship in a unique context and can inform the development of targeted public health strategies and interventions in China.

Method

Sample population

Our data sample was extracted from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), a prestigious longitudinal study that serves as a flagship initiative of the National Development Institute at Peking University. CHARLS is dedicated to the systematic collection of high-quality microdata, focusing on households and individuals across Chinese communities who are aged 45 years and above. The design and protocol of this work were approved by the Peking University Ethics Review Board (approval No. IRB00001052-11014), and informed consent was obtained from all participants. For those seeking an in-depth understanding of the sampling methodologies and overall design of the study, comprehensive details are readily accessible at http://charls.pku.edu.cn/index/en.html.

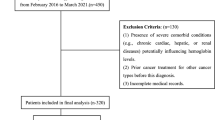

Fundamental demographic data, along with health status evaluations, thorough physical examinations, and blood test results, were meticulously gathered during the inaugural phase (2011–2012, Wave 1) and the subsequent follow-up phase (2015–2016, Wave 3). CHARLS included a total of 17,708 participants in Wave 1. After participants with incomplete cognitive assessments (N = 606), those lacking hemoglobin assessment data (N = 6178), and those below the age threshold of 45 years (N = 386) were excluded, an initial cohort of 10,537 eligible subjects was retained for the present study. Upon the baseline visit of those 10,537 participants, 3593 did not undergo hemoglobin concentration testing, 139 were absent for cognitive reassessment, 661 were not evaluated for body mass index (BMI), and 1623 did not receive serum cystatin C testing, ultimately reducing the analytical cohort to 4521 participants. The detailed exclusion process is shown in Fig. 1.

Assessment of cognitive function

Cognitive function within CHARLS was based on concepts similar to those of the American Health and Retirement Study (HRS). This research utilized two primary cognitive measures. The first was episodic memory, which was evaluated through a word recall task. The participants were asked to immediately repeat, in any order, ten Chinese nouns that were just read to them (immediate word recall, scored 0–10) and to recall the same list of words approximately four minutes later (delayed recall, scored 0–10). The episodic memory score was calculated by the average number of immediate and delayed words recalled on a scale of 0–10. The second cognitive measure was mental status, derived from components of the Telephone Interview of Cognitive Status (TICS) battery, which was designed to capture the cognitive intactness or mental state of individuals. The mental status questions comprised tasks such as serially subtracting 7 from 100 (up to five times, scored 0–5), naming today’s date (month, day, year, and season, scored 0–4), identifying the day of the week (scored 0–1), and demonstrating the ability to redraw a picture shown to them (visuo-construction, scored 0–1). The responses to these questions were aggregated into a single mental status score that ranged from 0 to 11. An aggregate measure of global cognitive performance was derived by combining the scores from the two measurements, yielding a total score spectrum from 0 to 21. This measure of cognitive function has been used in previous studies9,26,27. Low cognitive performance (LCP) was defined as cognitive scores below the mean minus 1.5 standard deviations28,29.

Blood tests and definition of anemia

The participants, who had been instructed to fast overnight, provided blood samples that were collected by a team of medically trained professionals at their local medical facilities, including regional centers for disease control (CDCs) and county-level disease prevention and control centers in urban settings, as well as town or village health centers in rural locations. The samples were subsequently sent to a laboratory and stored at 4 °C. Other fresh venous blood was centrifuged into plasma, sedimented into brownish-yellow layers, and stored at − 20 °C before being transported to the central laboratory in Beijing for other blood biochemical analyses within 2 weeks. The mean corpuscular volume (MCV, fL) and hemoglobin concentration (g/dL) were evaluated via automated analyzers that were accessible at centrally controlled sites. Serum creatinine levels were measured via the rate-blanked and compensated Jaffe method. Blood lipid profiles, including total cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL cholesterol), were determined through enzymatic colorimetric tests. The detection procedures were performed at the Youanmen Center for the Clinical Laboratory of Capital Medical University. All laboratories involved in those analyses had standardized accreditation. According to WHO criteria, anemia was defined as a hemoglobin (Hb) level of < 13 g/dl in men and < 12 g/dl in women. To account for potential assay differences over time, the 2015 CHARLS Hb values were adjusted to match the distribution of the 2011 baseline values; this made the distributions of the Hb of the CHARLS respondents the same in 2011 and 2015, with no change over time at the national level changes at the individual level30. The distributions of Hb among the participants in the 2 waves are shown in Fig. S2. A detailed description of the adjustment is provided in the Supplementary Material.

Other covariates

Potential covariates, including demographic variables and health-related factors, were assessed at the baseline survey; these covariates included age, sex, education, cigarette smoking status, alcohol consumption status, and comorbidities. Education level was categorized as primary school or below or middle school or above. Additional health-related factors included self-reported physician-diagnosed chronic conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia. BMI was derived from direct height and weight based on the standard formula kg/m2 and classified into three levels: < 18.5, 18.5–23.9, and ≥ 24 kg/m2. We calculated the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) on the basis of the 2012 CKD-EPI cystatin C equation:133 × min(Scys/0.8, 1)−0.499 × max (Scys/0.8, 1)−1.328 × 0.996Age [× 0.932 if female], where Scys is serum cystatin C, min indicates the minimum of Scys/0.8 or 1, and max indicates the maximum of Scys/0.8 or 131.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables, including age, BMI, hemoglobin levels, MCV, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (Hs-CRP), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, the eGFR, and global cognitive function scores, are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs). Categorical variables comprising education, smoking status, alcohol consumption status, hypertension status, diabetes status, and dyslipidemia status are presented as frequency counts with percentages [n (%)]. Initially, we performed longitudinal unidirectional analyses via linear regression to explore the link between baseline anemia status and the Cognitive Test Scores of Visit 2 in participants free from LCP at baseline. Binary logistic regression was subsequently used to assess the relationship between baseline cognitive scores and the subsequent risk of developing anemia, with the analysis excluding participants who presented with anemia at baseline. Regression coefficients (β) or odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated with 3 models. Model 1 was unadjusted. Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, and education level. Model 3 was additionally adjusted for hypertension status, diabetes status, dyslipidemia status, smoking status, alcohol consumption status, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein levels, the eGFR, MCV, and BMI. Owing to the different definitions of anemia by sex, we decided to present all the results stratified by sex and to explore whether there was a sex-specific difference with respect to the relationship between anemia status and cognitive decline. Given that we had only two time points capturing cognition and anemia, the cross-lagged panel model (CLPM) was the selected dynamic, bidirectional model in our analysis. For the fully adjusted CLPM, a comprehensive set of variables, including baseline sociodemographic characteristics—such as age, sex, and education level—as well as clinical factors such as hypertension status, diabetes status, dyslipidemia status, smoking status, alcohol consumption status, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein level, the eGFR, the MCV, and BMI were included. As depicted in the flow diagram, we initially performed listwise deletion for certain variables with missing data. For the primary analyses, we used full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation across all the models to handle missing data. FIML estimation is deemed a suitable approach when data are missing at random32 and can be used to minimize estimation bias by leveraging all available data33. Model fit was rigorously assessed via a set of indices: a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) value below 0.06, a comparative fit index (CFI) above 0.90, and a Tucker‒Lewis index (TLI) above 0.90, all of which indicate a well-fitting model. All analyses were conducted via SPSS 27.0 (Inc., Chicago, IL), R version 4.2.1 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria) and Mplus version 8.0 (Muthén and Muthén). A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the participants

A total of 4521 participants were included in the analysis, with 3956 individuals in the nonanemia group and 565 in the anemia group. The baseline characteristics of the study sample, stratified by anemia status, are presented in Table 1. The participants in the anemia group were significantly older than those in the nonanemia group were. The anemia group also presented a significantly lower mean BMI, lower mean WBC count, and lower mean MCV. Conversely, the anemia group had a significantly greater mean Cyc, mean HDL cholesterol, and mean C-reactive protein. Both baseline (2011) and follow-up (2015) cognitive scores were significantly lower in the anemia group. With respect to the categorical variables, the anemia group had a significantly greater proportion of females and a lower proportion of participants with hypertension and dyslipidemia. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in terms of education level, diabetes incidence, alcohol consumption status, or smoking status.

Longitudinal incidence of anemia and low cognitive performance

Among the longitudinal study sample of 4,079 participants who did not have LCP at baseline, 366 individuals, representing 9.0% of the cohort, developed new-onset MCI over the follow-up period. The incidence rates of LCP for the baseline groups, stratified by the absence and presence of anemia, were 8.6% and 11.6%, respectively. This disparity was statistically significant (P = 0.027), as depicted in Fig. S1, Panel A. Furthermore, within the longitudinal cohort initially free from anemia, 3,956 individuals, 607 older adults (15.3%) developed anemia. The incidence rates of anemia in the baseline normal cognitive function and LCP groups were 14.8% and 20.2%, respectively, which were also significantly different (P = 0.006) (Fig. S1, Panel B).

In the adjusted hemoglobin distribution for 2015, no new cases of anemia were observed; therefore, no further analysis was conducted.

The relationship between baseline anemia status and follow-up cognitive performance

Table 2 presents the associations between baseline anemia status and follow-up cognitive function across different adjustment models and participant groups. In the unadjusted model, anemia status was significantly associated with lower cognitive function in all participants (β = − 0.89, 95% CI: − 1.29, − 0.49, p < 0.001) and males (β = − 1.23, 95% CI: − 1.77, − 0.70, p < 0.001) but not in females (β = − 0.47, 95% CI: − 1.03, 0.08, p = 0.092). After adjusting for covariates, the association remained significant in all participants and became significant in females (β = − 0.83, p = 0.003). Conversely, the association was no longer significant in males in the adjusted models (β = − 0.12, p = 0.670), suggesting sex-specific effects after accounting for confounders.

The relationship between baseline cognition and follow-up anemia status

The results of binary logistic regression analysis of 3956 participants without baseline anemia are summarized in Table 3. The results of the crude model revealed that the initial cognitive score was associated with subsequent anemia status in all participants (OR = 0.96, 95% CI: 0.94, 0.98, p < 0.001) and after sex stratification (men OR = 0.96, 95% CI 0.93–0.99, p = 0.011; women OR = 0.96, 95% CI 0.94–0.98, p < 0.001). According to the results, higher baseline cognitive function at baseline was associated with a lower risk of developing anemia at follow-up, without sex differences. The results of Model 3 revealed that the initial cognitive score was not significantly associated with follow-up anemia status in all participants (OR = 0.99, 95% CI 0.98–1.02, p = 0.836) but was slightly significantly related to follow-up anemia status in women (men OR = 1.02, 95% CI 0.98–1.06, p = 0.402; women OR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.94–0.99, p = 0.043).

Longitudinal bidirectional association between anemia status and cognition

The path diagram of the CLPM between cognition and anemia status, adjusted for age, sex, education level, hypertension status, diabetes status, dyslipidemia status, smoking status, alcohol consumption status, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein levels, the eGFR, MCV, and BMI, is shown in Fig. 2. The standardized coefficients of the CLPM results are shown in Table 4. The final model was saturated (RMSEA = 0.00, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00). Anemia status was associated with lower subsequent cognition (β = − 0.04, p = 0.02). A lower baseline cognitive score was associated with a greater risk of developing anemia (β2 = − 0.02, p = 0.04). Sensitivity analyses were performed to examine the extent to which the findings remained robust after adjusting for individuals without brain damage, intellectual disability, or memory-related diseases at two time points, and the analyses did not include MCV or the eGFR. The results from these models revealed a similar overall pattern of findings.

Cross-lagged model for anemia and cognitive function. In the panel, path 1 show the association between baseline anemia and followup anemia; path 2 show the association between baseline cognition and followup anemia; path 3 show the association between baseline anemia and follow-up cognition; path 4 show the association between baseline cognition and followup cognition; path 5 show the covariance between baseline anemia and baseline.

Discussion

Using a 4-year longitudinal study of Chinese adults aged 45 years and above, we investigated the reciprocal relationship between anemia status and cognition. Our fully adjusted CLPM provided evidence for a bidirectional longitudinal relationship between anemia status and cognition. The standardized cross-lagged path coefficient suggested a stronger influence of baseline anemia status on later cognitive performance than vice versa.

First, consistent with previous studies, we also found a negative effect of anemia status on follow-up cognition by conducting research in Chinese community-dwelling adults without baseline MCI. For example, by using the Korean National Health Insurance Service-National Health Screening Cohort (NHIS-HEALS) database, Jeong et al. reported that anemia status was associated with the incidence of dementia (HR = 1.32)34. Another prospective cohort study including 7180 community-dwelling participants (mean age 83 years and 59.5% women) revealed that anemia status was strongly associated with dementia and cognitive decline (DCD) and that the greater the severity of anemia was, the greater the risk of developing DCD25. In addition, one study with 207,203 elderly persons (with a mean age of 64.13 years and 52.52% women) reported that anemic persons had faster declines in global cognition and processing speed and a greater risk of developing dementia11. Second, in contrast, our study not only supported the evidence for a temporal one-way relationship between anemia status and cognitive function but also revealed a bidirectional relationship. Several mechanisms can explain this result: anemia can lead to insufficient oxygen supply to the brain or decreased oxygenation of brain tissue, which may lead to decreased cerebral perfusion35 and impaired brain function (i.e., vascular mechanisms)16. Third, the anoxic state may drive the fractional anisotropy of white matter microstructure integrity to decrease36. Finally, hemoglobin has also been reported to alter the Aβ aggregation state37 and suppress Aβ-mediated inflammatory reactions38.

Although these relationships were incompletely explored in previous studies, their results suggested that lower cognitive function was a potential risk factor for certain health outcomes (such as anemia). Case‒control research from the Taiwan Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2000 with a sample of 16,600 general participants revealed that dementia was associated with iron deficiency anemia. However, this significant relationship was cross-sectional, not longitudinal39. A more recent prospective study with 974 participants without anemia suggested that cognitive decline is a risk factor for the development of anemia in older women18. Consistent with the findings of previous studies, our results similarly suggested that a higher baseline cognitive score was associated with a low incidence of anemia during follow-up in middle-aged women. Therefore, our study contributes new evidence to support the temporal one-way relationship between cognitive function and the risk of developing anemia, making the current findings an important and novel contribution to the literature. The proposed pathophysiological pathways underlying the association between cognitive decline and anemia may involve multifactorial mechanisms, mediated through (1) nutritional deficiencies secondary to impaired dietary intake regulation17, (2) compromised self-care capacity affecting iron supplementation adherence40, and (3) chronic low-grade inflammation disrupting erythropoiesis41.

The sex stratification analyses indicated that sex significantly influenced the positive relationship between anemia status and cognition, with a stronger association detected among women. However, sex differences are important due to their occurrence in Alzheimer’s disease42,43. Additionally, sensitivity analyses after excluding participants with self-reported brain damage, mental retardation, or memory-related diseases and not adjusting for MCV and eGFR did not reveal a significant longitudinal bidirectional relationship between anemia status and cognitive function. This finding might suggest that the relationship between anemia status and cognition is not influenced by iron deficiency, vitamin deficiency, or renal function.

In addition, to observe the bidirectional association between anemia status and cognition in the same population and within the same timeframe in parallel, we verified these findings with a CLPM. The results revealed that anemia status and cognition were reciprocally linked and that greater anemia severity was more likely to be a cause than a result of poorer cognition. Although no studies to date have examined this bidirectional association, several previous findings might support our results. For example, both observational and prospective studies have shown that anemia status is reciprocally associated with cognitive function10,41,44,45. In addition, two systematic reviews reported a possible bidirectional causal association between anemia status and cognition12,13. However, the limitations in the study design made it impossible to prove the existence of a simultaneous bidirectional relationship. Unlike previous studies, our CLPM results revealed a bidirectional association between anemia status and cognition in community-dwelling Chinese adults aged 45 years or above, providing stronger evidence for the bidirectional causal relationship. Shared biological pathways, including inflammation, vascular dysfunction, and iron metabolism, underlie the bidirectional relationship between anemia status and cognitive function11,46. Sex differences significantly influence these mechanisms and the observed associations47. The results imply that interventions for either anemia or cognitive decline may have reciprocal benefits over time.

Strengths and limitations

The current study has several strengths. First, a large sample from a population-based prospective cohort, controls for a series of potential confounders, and additional robustness checks help minimize selection bias and confirm the validity of our findings. Second, we expand on prior research on the bidirectional association between anemia status and cognition by designing a longitudinal study based on a CLPM. Third, to the best of our knowledge, this research is the first longitudinal study in which the temporal bidirectional association between anemia status and cognition is evaluated via a CLPM. Fourth, we adjust for several potential factors that might have contributed to a confounding effect on the bidirectional association, such as age, sex, education level, hypertension status, diabetes status, dyslipidemia status, smoking status, alcohol consumption status, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein levels, the eGFR, MCV, and BMI.

However, several limitations of this study should be addressed. First, owing to the potential interwave variability in hemoglobin measurements, future research should include sensitivity analyses of individual variability. Second, the brief interval between two waves may not have been sufficient to adequately capture cumulative changes in cognitive function or anemia status in this age group. An extended period of follow-up is needed to more conclusively evaluate the true magnitude of the hypothesized bidirectional associations. Third, residual and unmeasured confounding factors are likely. While we considered numerous potential confounders, there are still unmeasured variables that could introduce bias. Fourth, the CLPM approach undertaken to test bidirectionality depends on several assumptions, which are often violated or cannot be entirely met48. Fifth, to ensure the comparability of biomarker measurements across different study waves, we implemented an adjustment to mitigate the impact of assay changes. However, this adjustment may have inadvertently reduced the ability to detect novel variations or changes in anemia status between the two waves. In future studies, larger sample sizes or data from multiple regions may be necessary to enhance the robustness and generalizability of the findings. Finally, the generalization of the association between anemia status and cognition may be limited, as our work was conducted among middle-aged and older individuals living in China.

Conclusions

The main finding of this study is that the association between anemia status and cognitive function is both unidirectional and bidirectional. Baseline anemia status is associated with poor cognitive function at follow-up, and higher baseline cognitive function is associated with a lower risk of follow-up anemia. The observed bidirectional relationship suggests that interventions targeting anemia or cognitive decline may yield reciprocal advantages over time, potentially contributing to the promotion of healthy aging. Further investigations are warranted to validate these findings and explain the underlying mechanisms involved.

Data availability

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are publicly available in the https://opendata.pku.edu.cn/dataverse/CHARLS.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- TICS:

-

The telephone interview of cognitive status

- MCV:

-

The mean corpuscular volume

- eGFR:

-

The estimated glomerular filtration rate

- Hs-CRP:

-

Hypersensitive C-reactive protein

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- Ors:

-

Odds ratios

- 95%:

-

95% Confidence interval

- HRS:

-

American Health and Retirement Study

- CHARLS:

-

China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study

- CLPM:

-

Cross-lagged panel model

- RMSEA:

-

Root mean square error of approximation

- MCI:

-

Middle cognitive impairment

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- CFI:

-

Comparative fit index

- TLI:

-

Tucker–Lewis index

- DCD:

-

Dementia and cognitive decline

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- WBC:

-

White blood cell count

References

National Bureau of Statistics. The seventh national census of China. 2021.

Lindenberger, U. Human cognitive aging: Corriger la fortune?. Science 346, 572–578. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1254403 (2014).

Ponjoan, A. et al. Epidemiology of dementia: Prevalence and incidence estimates using validated electronic health records from primary care. Clin. Epidemiol. 11, 217–228. https://doi.org/10.2147/clep.S186590 (2019).

Katsumi, A., Abe, A., Tamura, S. & Matsushita, T. Anemia in older adults as a geriatric syndrome: A review. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 21, 549–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.14183 (2021).

Schneider, A. L. et al. Hemoglobin, anemia, and cognitive function: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 71, 772–779. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glv158 (2016).

Yang, Y. et al. Association between hemoglobin level and cognitive profile in old adults: A cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5806 (2022).

Marzban, M. et al. Association between anemia, physical performance and cognitive function in Iranian elderly people: Evidence from Bushehr Elderly Health (BEH) program. BMC Geriatr. 21, 329. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02285-9 (2021).

Dlugaj, M. et al. Anemia and mild cognitive impairment in the German general population. J. Alzheimers Dis. 49, 1031–1042. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-150434 (2016).

Qin, T. et al. Association between anemia and cognitive decline among Chinese middle-aged and elderly: Evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr. 19, 305. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1308-7 (2019).

Shah, R. C., Buchman, A. S., Wilson, R. S., Leurgans, S. E. & Bennett, D. A. Hemoglobin level in older persons and incident Alzheimer disease: Prospective cohort analysis. Neurology 77, 219–226. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e318225aaa9 (2011).

Wang, J. et al. Association of anemia with cognitive function and dementia among older adults: The role of inflammation. J. Alzheimers Dis. 96, 125–134. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-230483 (2023).

Andro, M., Le Squere, P., Estivin, S. & Gentric, A. Anaemia and cognitive performances in the elderly: A systematic review. Eur. J. Neurol. 20, 1234–1240. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.12175 (2013).

Kim, H. B., Park, B. & Shim, J. Y. Anemia in association with cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 72, 803–814. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-190521 (2019).

Kung, W. M. et al. Anemia and the risk of cognitive impairment: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11060777 (2021).

Hare, G. M. Anaemia and the brain. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 17, 363–369. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001503-200410000-00003 (2004).

Gottesman, R. F. et al. Patterns of regional cerebral blood flow associated with low hemoglobin in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 67, 963–969. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gls121 (2012).

Volkert, D. et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in dementia. Clin. Nutr. 34, 1052–1073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2015.09.004 (2015).

Noma, T. et al. Lower cognitive function as a risk factor for anemia among older Japanese women from the longitudinal observation in the SONIC study. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 23, 334–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.14571 (2023).

Wang, Y., Ping, Y. J., Jin, H. Y., Ge, N. & Wu, C. Prevalence and health correlates of anaemia among community-dwelling Chinese older adults: The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. BMJ Open 10, e038147. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038147 (2020).

Yu, W. et al. Associations between malnutrition and cognitive impairment in an elderly Chinese population: An analysis based on a 7-year database. Psychogeriatrics 21, 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12631 (2021).

Feng, L. et al. Malnutrition is positively associated with cognitive decline in centenarians and oldest-old adults: A cross-sectional study. EClinicalMedicine 47, 101336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101336 (2022).

Wang, L. Y., Hu, Z. Y., Chen, H. X., Zhou, C. F. & Hu, X. Y. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and its association with malnutrition in older Chinese adults in the community. Front. Public Health 12, 1407694. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1407694 (2024).

Deng, Q. & Liu, W. Inequalities in cognitive impairment among older adults in China and the associated social determinants: A decomposition approach. Int. J. Equity Health 20, 82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01422-5 (2021).

Shilian, H., Jing, W., Cui, C. & Xinchun, W. Analysis of epidemiological trends in chronic diseases of Chinese residents. Aging Med. (Milton) 3, 226–233. https://doi.org/10.1002/agm2.12134 (2020).

Weiss, A. et al. Association of anemia with dementia and cognitive decline among community-dwelling elderly. Gerontology 68, 1375–1383. https://doi.org/10.1159/000522500 (2022).

Xu, T. et al. Association between solid cooking fuel and cognitive decline: Three nationwide cohort studies in middle-aged and older population. Environ. Int. 173, 107803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2023.107803 (2023).

Zheng, G. et al. Long-term visit-to-visit blood pressure variability and cognitive decline among patients with hypertension: A pooled analysis of 3 national prospective cohorts. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 13, e035504. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.124.035504 (2024).

Cong, L. et al. Mild cognitive impairment among rural-dwelling older adults in China: A community-based study. Alzheimers Dement 19, 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12629 (2023).

Dunne, R. A. et al. Mild cognitive impairment: The Manchester consensus. Age Ageing 50, 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afaa228 (2021).

Wu, Q., Ailshire, J. A., Kim, J. K. & Crimmins, E. M. The association between cardiometabolic risk and cognitive function among older Americans and Chinese. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glae116 (2024).

Inker, L. A. et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl. J. Med. 367, 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1114248 (2012).

Enders, C. K. Dealing with missing data in developmental research. Child Dev. Perspect. 7, 27–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12008 (2013).

Lövdén, M. et al. Changes in perceptual speed and white matter microstructure in the corticospinal tract are associated in very old age. Neuroimage 102(Pt 2), 520–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.08.020 (2014).

Jeong, S. M. et al. Anemia is associated with incidence of dementia: A national health screening study in Korea involving 37,900 persons. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 9, 94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-017-0322-2 (2017).

Wolters, F. J. et al. Hemoglobin and anemia in relation to dementia risk and accompanying changes on brain MRI. Neurology 93, e917–e926. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000008003 (2019).

González-Zacarías, C. et al. Chronic anemia: The effects on the connectivity of white matter. Front. Neurol. 13, 894742. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.894742 (2022).

Chuang, J. Y. et al. Interactions between amyloid-β and hemoglobin: Implications for amyloid plaque formation in Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE 7, e33120. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0033120 (2012).

Sankar, S. B., Donegan, R. K., Shah, K. J., Reddi, A. R. & Wood, L. B. Heme and hemoglobin suppress amyloid β-mediated inflammatory activation of mouse astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 11358–11373. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA117.001050 (2018).

Chung, S. D., Sheu, J. J., Kao, L. T., Lin, H. C. & Kang, J. H. Dementia is associated with iron-deficiency anemia in females: A population-based study. J. Neurol. Sci. 346, 90–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2014.07.062 (2014).

Volkert, D. et al. ESPEN guideline on nutrition and hydration in dementia-update 2024. Clin. Nutr. 43, 1599–1626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2024.04.039 (2024).

Denny, S. D., Kuchibhatla, M. N. & Cohen, H. J. Impact of anemia on mortality, cognition, and function in community-dwelling elderly. Am. J. Med. 119, 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.08.027 (2006).

Fisher, D. W., Bennett, D. A. & Dong, H. Sexual dimorphism in predisposition to Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 70, 308–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.04.004 (2018).

Tokatli, M. R. et al. Hormones and sex-specific medicine in human physiopathology. Biomolecules https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12030413 (2022).

Deal, J. A., Carlson, M. C., Xue, Q. L., Fried, L. P. & Chaves, P. H. Anemia and 9-year domain-specific cognitive decline in community-dwelling older women: The Women’s Health and Aging Study II. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 57, 1604–1611. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02400.x (2009).

Atti, A. R. et al. Anaemia increases the risk of dementia in cognitively intact elderly. Neurobiol. Aging 27, 278–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.02.007 (2006).

Snyder, B., Simone, S. M., Giovannetti, T. & Floyd, T. F. Cerebral hypoxia: Its role in age-related chronic and acute cognitive dysfunction. Anesth. Analg. 132, 1502–1513. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000005525 (2021).

Cui, S. S., Jiang, Q. W. & Chen, S. D. Sex difference in biological change and mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease: From macro- to micro-landscape. Ageing Res. Rev. 87, 101918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2023.101918 (2023).

Kearney, M. W. Cross-lagged panel analysis. 2016

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study Team for providing the data and training on how to use the datasets. We thank all the volunteers and staff involved in this research.

Funding

No.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conducted and designed the research: JX, YJ, JW, DZ and WX. Analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript: JX. Primary responsibility for the final content: DZ and WXX. All authors revised it critically for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research analyzed data downloaded from the CHARLS. The CHARLS survey protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Peking University. Informed consent to participate was obtained from all participants in the study. And the study methodology was carried out in accordance with approved guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiong, J., Jiang, Y., Wu, Jl. et al. Bidirectional relationship between anemia and cognitive function in middle-aged and older Chinese adults: a longitudinal study. Sci Rep 15, 26080 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11830-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11830-0