Abstract

Recent Monkeypox virus (MPXV) outbreaks in non-endemic regions have highlighted the need for genomic surveillance to support epidemiological investigations and monitor viral evolution. In this paper we present the results of genomic characterization and analyses of mechanisms of human adaptation, including APOBEC-style mutations, performed on 11 MPXV isolates, collected from May to September 2022, from Emilia-Romagna (Italy). Phylogenetic analysis confirmed all strains belonged to Clade IIb. Viruses from male patients were classified within lineage B (sub-lineages B.1, B.1.3, B.1.12), while a strain from a female patient was assigned to lineage A (A.2.3), with epidemiological links to Ghana. This represents the fourth detection of an A.2.3 strain of African origin outside the continent. Disruptions were identified in two genes: OPG176 (similar to VACV-Cop A46R), as reported in lineage A, and OPG023 (similar to VACV-Cop D7L), resulting in protein truncation that may suggest a possible pattern of human adaptation. These findings further enhance our understanding of MPXV Clade IIb diversity through characterization of a rarer variant giving insights from a less explored epidemiological pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Monkeypox virus (MPXV) species in the genus Orthopoxvirus, Poxviridae family, includes two major clades, the formerly Congo Basin (clade I) and West Africa (clade II). According to the WHO global Mpox trends1the current landscape is characterized by the spread of different sub-clades of clades I (Ia and Ib) and clade II (IIa and IIb) showing varied transmission pathways and impacting diverse populations in different geographic regions. Clade Ia is endemic in multiple Central African countries and characterized by spillovers to humans from animal reservoirs with reported human to human transmission. A concerning development has been the emergence in 2023 of clade Ib, a novel variant of clade I, which spreads primarily through sexual networks2,3. Clade Ib first appeared among sex workers in Kamituga, DRC and now affects different provinces in the country. Cases were reported also in other countries in Africa, particularly Burundi and Uganda, and outside the continent due to travelling. Clade Ib is undergoing sustained human to human transmission, causing severe clinical symptoms in all age groups, especially in young children getting infected through household contacts2. Clade IIa is spread in Western and Central Africa being responsible of a limited number of cases in humans as primarily associated with animals1.

In 2022, the world experienced the global re-emergence of MPXV showing unique features with the highest number of cases being associated with human-to-human transmission and affecting mainly young men who identify as gay or bisexual and other men who have sex with men (MSM), with different clinical presentations4. Only few clinical cases were reported in women5. The causative B.1 global lineage belongs to MPXV clade IIb, referred to as hMPXV16, was imported from West Africa. In 2017, West Africa and particularly Nigeria experienced the largest MPXV outbreak in history, showing a marked demographic shift with more infected individuals of 30 to 40 years and higher incidence in urban settings7. In September 2018, for the first time, a human host was identified as the cause of MPXV transfer from Africa to Europe and Asia8.

Since the identification of the B.1 lineage, several countries have reported other lineages that fall outside the B.1 diversity9. In fact, multiple clade IIb viruses designated as lineage A.2 have been found outside Africa since 2017. This lineage was shown to be circulating out of Africa before the global B.1 outbreak being sustained by human-to-human transmission. It was speculated that lineage A originated from a single zoonotic event and persisted in the human population for years.

Before the global 2022 outbreak, most of the MPXV research was focused on the African continent, particularly the Democratic Republic of Congo and Nigeria, however, very few sequences from human cases had been filed in databases. Following the pandemic, the study sites and provenance of research groups on MPXV diversified, with publications of numerous case reports from many parts of the world10. Nonetheless, active genomic and disease surveillance was not carried out with uniformity in all affected countries. Genomes published during the 2022 outbreak to date were attributed to a common ancestor with MPXV sequences from Nigeria (Clade IIb). Several authors9 observed that clade IIb MPXV are evolving at higher rates compared to what is expected from a double-stranded DNA virus and reported an increased mutational signature in response to the action of human APOBEC3 (apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide) deaminases, a host enzyme with antiviral function. APOBEC genomic editing was claimed to be a characteristic feature of the sustained transmission in the human population as it was not observed in sequences from zoonotic infections11. On the other hand, the limited availability of sequences from Nigeria’s neighboring countries may have created a bias in our understanding of viral evolution and phylogenetic relationships, as most of the genomic data come from viruses linked to or identified in this country12.

The scarcity of information makes it complex to fully understand the evolutionary dynamics of the virus in its less explored epidemiological pathways: outside the target MSM community and in countries that carried out less punctual epidemiological and molecular surveillance compared to Nigeria.

In this study, whole-genome sequencing was conducted on 11 MPXV isolated in Emilia Romagna (Italy) in 2022. Our findings show the co-circulation of clade IIb viruses of sub-lineages A in addition to the most widely reported viruses belonging to lineage B, during the 2022 pandemic. In fact, the infection in the only female patient, traced back to Ghana, was caused by a strain belonging to MPXV sub-lineage A.2.3. Given the limited information on lineage A variants circulating outside the African continent, we explored the evolutionary dynamics, key genomic, and amino-acid mutations of sub-lineage A.2.3 strains, to identify emergency mutations and discuss mechanisms for host adaptation. Overall, our results underline the importance of continuing to study MPXV outside its usual geographic routes and infection pathways to gain new insights on non-zoonotic spread to finally improve control and prevention strategies.

Results

Phylogenetic characteristics of MPXV isolated in Emilia-Romagna

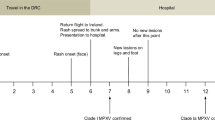

Eleven MPXV strains, isolated, between May and September 2022 in Emilia Romagna, from 10 males and 1 female patients, were submitted for genomic characterization. All the MPXV samples were preliminarily tested through real-time PCR and confirmed as Clade IIb13. To explore the molecular evolution and genomic characteristics of MPXV associated with the Emilia-Romagna outbreak, isolates underwent whole-genome sequencing. An initial phylogenetic tree on Nextclade (https://clades.nextstrain.org) confirmed that all the analyzed isolates clustered with clade IIb. By integrating the 11 MPXV sequences obtained from Emilia-Romagna with a curated dataset of 267 high-quality Clade II MPXV genomes (Supplementary Table S1), phylogenetic analyses revealed that all strains isolated from male patients grouped within lineage B, being distributed across different sub-lineages: B.1 (n = 5), B.1.3 (n = 3), and B.1.12 (n = 2) (Fig. 1). Specifically, the sequences hMPXV/P1/2022, hMPXV/P4/2022, hMPXV/P9/2022, hMPXV/P10/2022, and hMPXV/P15/2022 clustered within lineage B.1 with strong bootstrap support (> 80). The sequences hMPXV/P3/2022, hMPXV/P5/2022, and hMPXV/P6/2022 were grouped within lineage B.1.3, supported by high bootstrap values (> 90). While hMPXV/P7/2022 and hMPXV/P13/2022 clustered within lineage B.1.12, although with lower bootstrap support (< 50). In contrast, the isolate hMPXV/P12/2022, collected from the only female patient, clustered within lineage A, sub-lineage A.2.3. with maximal bootstrap support (100). Epidemiological data indicated that this case was linked to travelling from Ghana to Italy (Table 1).

These results were further confirmed by the phylogenetic analysis performed using the Nextclade tool.

Phylogenetic Analysis of 11 MPXV Genomes from Emilia-Romagna. The Maximum Likelihood tree was built based on the whole-genome alignment of the 11 Italian MPXV sequences obtained in this study, alongside 267 high-quality clade IIb MPXV genomes retrieved from NCBI GenBank (as of October 4, 2024). The tree was rooted using three clade IIa sequences, with outgroup sequences highlighted in light brown. Tree labels are color-coded by lineage. Bold red labels in the tree indicate the 11 sequences from this study emphasized in bold red. Black dots indicate bootstrap support, with only values > 70 shown, while nodes with bootstrap values < 20 were collapsed. The scale bar represents the number of nucleotide substitutions per site. The tree was inferred using IQ-TREE v.2.1.4, with automated model selection (best fit model was HKY + F + R4 according to Bayesian Information Criterion) and 10,000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates. The middle annotation ring indicates the isolation location of each MPXV genome, while the outer annotation ring indicates the corresponding isolation date.

Sequences from lineage A and its related sub-lineages were retrieved and analysed in detail. As confirmed by sequences available in both NCBI GenBank and GISAID, most lineage A sequences have been isolated from the African continent, particularly Nigeria. In contrast, the few A.1.1 sequences, available in public databases, have been identified in a more diverse range of geographical regions, including the USA, Italy, and Thailand (Fig. 2).

Geographic distribution of MPXV A sub-lineages. The map illustrates the global distribution of MPXV A sub-lineages, highlighting their widespread presence, particularly in the southern provinces of Nigeria. The map was generated using QGIS v.3.34.14 (http://www.qgis.org). In cases where detailed location data was unavailable, points were placed at the centroid of the respective countries where the virus was detected. The sequences used for this analysis include all lineage A sequences downloaded from NCBI as of October 4th.

Temporal increase of SNPs and APOBEC3 associated mutations in MPXV lineage A

APOBEC analysis confirmed that early MPXV samples, isolated between 2017 and 2020, generally showed lower APOBEC mutation counts, while those isolated between 2021 and 2024 show an increased range of mutation counts, including higher values in the 15 to 35 range (Fig. 3A). As expected, A.2 and A.3 sub-lineages generally exhibit higher APOBEC-style mutations, mostly covering a range of 16 to 35 counts, against the range covered by lineage A and A.1 which is 5 to 15 (Fig. 3B).

APOBEC-associated mutations in MPXV sub-lineages over time. (A) Yearly distribution of APOBEC-associated mutations per sample across different sub-lineages. Circles indicate samples retrieved from NCBI (accessed on October 4, 2024), whereas the cross denotes the sample sequenced in this study. (B) Number of APOBEC-associated mutations in MPXV clade IIb A sub-lineages.

In the analyzed A.2 lineage sequences, we found on average 57.3 SNPs (σ = 24.1) per sample. The high standard deviation can be explained by the presence of two samples (GenBank Accession Number: PP853014 and PP853015) with high numbers of SNPs, 110 and 94 respectively. In the A.2.1 sub-lineage (seven samples: three from South Korea, two from the USA, one from Egypt and one from the UK) we found on average 44.4 SNPs (σ = 5.9) per sample. In the A.2.2 sub-lineage, we analyzed fourteen samples (one from the UK and thirteen from Nigeria), with an average mutation number of 72.7 (σ = 23.4). In the A.2.3 sub-lineage, 47 samples, one from Australia, one from the USA, one from Italy and 44 from Nigeria showed an average number of mutations of 56.3 (σ = 15.7).

Analysis of SNPs and APOBEC-associated mutations in sub-lineage A.2.3

To gain deeper insight into the evolution pathway of the hMPXV/P12/2022, we conducted a detailed examination of SNPs and APOBEC-associated mutations within the whole sub-lineage A.2.3. This analysis identified 36 unique polymorphisms across the genome, including 3 A/G, 15 G/A, and 18 C/T substitutions (Fig. 4A). Of the observed G-to-A transitions, 54.4% occurred in an APOBEC context, of these 90.6% were specifically 5’ GA-to-AA while the remaining 9.4% were GG-to-AG. On the other hand, of the observed C-to-T transitions, 56.9% occurred in an APOBEC context, meaning a TC-to-TT mutations. The prevalent 5’ APOBEC mutation is TC-to-TT in strains of lineage A, representing 51.5% of all the APOBEC-style mutations, followed by the GA-to-AA mutation (44.0%). Considering the subset of strains of lineage A.2.3, the TC-to-TT mutation is also in this case the most present, being 50.8% of the APOBEC mutations in this subset, followed by 44.2% of GA-to-AA mutations (Fig. 4B).

Genomic variability and APOBEC mutations in the A.2.3 sub-lineage. (A) Histogram representing the detected variants in the A.2.3 sub-lineage in our dataset. Variants are expressed with the genomic position, the expected nucleotide in the reference genome for lineage A and the alternate nucleotide detected in our samples. The x-axis represents the genomic position and the corresponding SNP type. The y-axis expresses the count both in terms of absolute occurrences (left) and in terms of percentage with respect to this experimental dataset (right). (B) Histogram representing the APOBEC Mutation counts per sample categorized by mutation type in the A.2.3 sub-lineage. The x-axis displays the sequences included in our dataset. The y-axis represents the absolute number of APOBEC-style mutations.

Signature mutations and gene disruption in A.2.3 sub-lineage

Four specific transitions were found in genomes belonging to lineage A.2.3 at positions 57,284 (C/T), 146,223 (C/T), 170,317 (G/A), and 175,759 (C/T). These are associated with alterations to the protein primary sequence. They are in the OPG075 (Glutaredoxin-1, R72K), OPG170 (Chemokine binding protein, D186N), OPG198 and OPG205 (Ser/thr kinase, D94N) and (Ankyrin repeat protein, A35V). Overall, hMPXV/12/2022 showed a total of 47 single SNPs relative to the reference MPXV-M5312_HM12_Rivers (GenBank Accession Number: NC_063383) causing alterations in the primary protein sequences 14. Of these, 3 were identified as strain specific: OPG023 leading to gene disruption at position 12,207 (G/A), OPG094 at position 74,420 (C/T) and OPG143 at position 122,712 (C/T) causing amino acid changes A214V and D202N respectively in the Entry/fusion complex component similar to VACV-Cop G9R and in a soluble myristilated protein similar to VACV-Cop A16L,

Another mutation was identified at OPG188 at position 161,953 (C/A) leading to an amino acid change (P314T). This nonsynonymous mutation appeared to be shared with 2 other strains of lineage A.2.3 isolated from Nigeria in 2022 and 2023 (GISAID: EPI ISL 19256279 and 19256278) and lead to a mutation in a schlafen-like protein similar to VACV-Cop B2R.

Concerning the MPXV replication complex, all the identified B sub-lineages of this study showed nonsynonymous mutations in OPG071 and OPG093 encoding respectively similar to the VACV-Cop F8L (RC catalytic subunit) and G9R (a processivity factor). In particular, a change at position 108 (F/L) of the encoded F8L and at position 30 (S/L) and 88 (D/N) of the G9R were observed. These mutations are ~ 100% prevalent in the strains that circulated during the 2022 pandemic. These mutations were not observed in the ancestor Nigeria 1971 (GenBank Accession Number: KJ642617.1) and lineage A (sub-lineages A.1, A.2, A.2.1, A.2.2, A.2.3) which conserves amino acid residues L at position 108 of the F8L and S and D at positions 30 and 88 of the G9R as identified in strains isolated by 2018. Sub-lineage A.1.1 seems to represent an exception, within the A lineage, as it resembles lineages B with F at position 108 of the F8L and L at position 30 of the G9R, while at position 88 of this protein A.1.1 shows the residue D as all the viruses of A lineage.

Two non-sense mutations were found in hMPXV/P12/2022 one of which was previously identified in other strains classified as A.2 sub-lineages. This nonsense mutation is in OPG176 encoding a IL-1/TLR signalling inhibitor similar to VACV-Cop A46R, that was reported to be compatible with APOBEC activity according to Ndodo et al.15. As previously described, this gene disruption is only found in lineage A.2. In fact, we were able to detect the mutation only in the strain A.2.3 hMPXV/P12/2022, but not in the strains belonging to B sub-lineages confirming that this genetic disruption is the consequence of hallmark adaptation event of the A.2 lineage16. This gene disruption leads to the translation of a polypeptide of 21 amino acids, instead of a whole-length protein of 240 residues. This variant was reported to be actively circulating among human hosts in West Africa and outside15.

A further gene disruption was found in the hMPXV/P12/2022 in the OPG023 encoding one of the MPXV Ankyrin repeat proteins similar to VACV-Cop D7L. The nucleotide G/A substitution at position 12,207 causes the appearance of a stop codon with subsequent protein truncation at amino acid position 232 (Q/*), which appeared to be a very rare variant, only found in another A.2.3 lineage strain detected in Nigeria in 2022 (GISAID: EPI ISL19256202). To characterize the previously unreported effects of the gene disruption in OPG023, we queried the reference database for protein search in UniProt17 (https://www.uniprot.org/). As expected, the 232 amino-acid residues truncated protein of hMPXV/P12/2022 (Fig. 5A) showed to be 100% identical to the Ankyrin repeat-containing protein PG023 of MPXV-M5312_HM12_Rivers (UniProt ID: A0A7H0DMZ9) which is overall 660 residues long. A 94% identity was identified with the D6L protein of the Variola virus isolate Human/India/Ind3/1967 (UniProt ID: Q07045). The protein superimposition with the VARV 452 residue long protein, modeled with the homology-based platform SWISS-MODEL (Fig. 5B) showed a high structural identity in the conserved ANK repeats, characterized by conserved domain of approximately 33 amino acids as originally identified in Ankyrin. These motifs have an L-shaped structure consisting of a beta-hairpin and two alpha-helices.

Structural modeling of hMPXV/P12/2022 and comparison with the D6L protein. (A) Structural AlfaFold3 model of hMPXV/P12/2022 The protein contains 12 Ankyrin repeats from the N to the C terminus. The computed average per-atom model confidence score is 84, indicating that residues are modeled on average with high quality (see “Methods”). (B) Structural model of D6L protein (Uniprot ID: Q07045). Model is computed by SWISS MODEL with an Average Model Confidence (QMEANDisCo) is equal to 0.58 ± 0.05 (see “Methods”). The protein length is 452 residues. The structural alignment of the models of hMPXV/P12/2022 with the D6L protein. The two models superimpose with a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 1.65 Å over 216 aligned residues (sequence identity is 94%).

Discussion

In this study we aimed to gain new insights on several MPXV isolates collected in Emilia Romagna (Italy) between May and September 2022. Our results are consistent with previous findings of Clade IIb lineage termed B.1 that rapidly disseminated around the world to cause the MPXV pandemic from 2022 on, spreading worldwide through human-to-human transmission18,19,20.

Ten out of eleven MPXV strains, analyzed in this study, were isolated from male patients, that identified as men who have sex with men (MSM) presenting lesions that suggested transmission during sexual intercourse10,18. These isolates were classified as sub-lineages B.1, and B.1.5 confirming previous findings from European countries including Italy21. MPXV classified as sub-lineage B1.12, previously reported in Ireland, Belgium, the United Kingdom and Germany22,23 showing its circulation also in Italy22,23.

The only woman, traced back to Ghana, belong to lineage A sub-lineage 2.3. According to NCBI GenBank and GISAID databases, this is the first A.2.3 lineage identified in Italy with no previous reports from Ghana. In fact, so far only few genomes, identified as A.2 and A.2.2 lineages, have been uploaded from this country. Sub-lineage A.2.3 has been rarely reported outside Africa specifically in USA, Australia and Portugal probably linked to individuals travelling from Africa. As shown in Fig. 2, sub-linage A.2.3. was previously identified in Egypt and Benin, but it is Nigeria where this variant seems to be widely spread (Fig. 2). Besides the 36 SNPs shared with all the A.2.3 strains. the MPXV isolates identified outside Africa do not share any other genetic variation, suggesting different sources.

Enrichment of mutations, due to the editing activity of human APOBEC3 deaminase, was shown to increase in time in all A sub-lineages confirming this signature as a characteristic feature of sustained transmission in the human population24,. The identified mutation spectrum dominated by TC-to-TT changes, have been shown to be extremely frequent in other human-specific Orthopoxviruses (OPXV) like Variola virus (VARV), the causative agent of smallpox. No preference toward TC-to-TT and GA-to-AA changes is observed in zoonotic Cowpoxvirus (CPXV), suggesting the antiviral APOBEC3 enzyme exposure on the evolution of different human-infecting Orthopoxviruses. Since MPXV adapts to human hosts through mutations in genes like F8, D1L and G9R enhancing viral replication and host receptor binding25we analyzed the protein variants of the 2 key factors of the MPXV replication complex: F8L and G9R encoded by OPG071 and OPG093 respectively. F8L is a B DNA polymerase (DNA pol), a critical enzyme for the replication and repair of genomic DNA, while G9R is a structural homologue of the human proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)26. While all our isolates classified as B lineage confirm to follow the typical patterns observed in the 2022 isolates, all the genomes of lineage A retain the amino acid residues identified as characteristic of the MPXV strains isolated by 2018. Alternative mutation patterns in the RC proteins were found in lineage A.1.1 genome. Given the limited availability of A1.1 sequences for the analysis, it is difficult to make any functional hypothesis on these RC key proteins of MPXV. However, this fluctuating pattern of mutations in A.1.1 key proteins of the RC seem to confirm sub-lineage A.1.1 as sister clade to lineage B, making this sub-lineage evolutionarily closer to the lineage B than to lineage A. Kannan et al.27 claimed that mutations in the F8L protein (L108F) and in the G9R protein (S30L and D88N), identified in the 2022 MPXV lineage B isolates, can change respectively processivity of F8L and sensitivity to nucleoside inhibitors, as well as the interaction of MPXV G9R with E4R (uracil DNA glycosylase). Given the retention of amino acid residues in two of the key RC proteins, it can be assumed that strains belonging to lineage A (except A1.1) followed a distinct evolutionary pathway compared to lineage B maintaining the functions of these proteins and sensitivity to the antiviral molecules in use27.

A gene disruption in the OPG176 encoding A46R was shown in all the genomes belonging to the A.2.3 lineage confirming this mutation in A2 lineages as reported by Ndodo et al.15. The VACV-Cop A46R shares amino acid sequence similarity with the Toll/IL-1 receptor (TIR) domain, having a key role in innate immunity and inflammation thus representing one of the poxvirus strategies to evade and neutralize the host immune response. The A46R protein is highly conserved in MPXV and it was assumed that the mutation found in all A.2 lineage, leading to the disruption of an immune modulator protein, can be considered a further sign of the virus adaptation to the human host. Since A46R was also found in Variola virus28it was suggested that viral evasion of TLR-induced immunity might contribute to the virulence of Variola virus in humans29. With the results obtained on A.2.3 sequences, we contribute to confirm that this mutation arose and persisted in the common lineage A ancestor as it spread globally. Besides A46R, we detected a further length polymorphism, caused by gene disruption, in the OPG023 encoding a D7L homologue30 in hMPXV/P12/2022. Previous studies performed on VACV showed that this protein is secreted by the infected host cell and interferes with the function of interleukin-18, a central signal molecule for antiviral responses by the innate and adaptive immune systems31. In MPXV, D7L has been indicated as one of the host range factors affecting the transmissibility of the virus and virulence. Several authors32,33 pointed out the importance of investigating some deletion or truncation in Ankyrin repeat gene family between VARV and MPXV as they can be related to different means of molecular evolution that may affect pathogenesis, host tropism, transmissibility and immunoregulation. An identical mutation leading to the same gene disruption was observed in only one other viral strain isolated in 2022 in Nigeria suggesting that this mutation may have arisen in a common ancestor. The truncated D7L overlaps with the D6L VARV homologue conserved domain making us speculate that this gene disruption can be a further sign of adaptation to human host given protein length reduction and truncation are known strategies used in OPXVs hosts adaptation. The fact that similar protein structures are found in VARV, the only OPXV with human-restricted host range, may also suggest that phenotypic effects are not preventing the biological activity of the truncated protein, but experimental analysis will be required to confirm this hypothesis. The vast majority of poxvirus ANK repeat proteins share a general molecular architecture that includes a conserved amino acid motif (F-box-like domain) at the carboxyl terminus interacting with cellular ubiquitin ligase complexes. F-box motifs are also known as Pox protein repeats of ankyrin C-terminal (PRANC) domains34,35,36. Premature stop-codons in some ANK/F-box genes is a common feature observed in Orthopoxviruses34,37 The gene disruption identified in the OPG023 of hMPXV/P12/2022 leads to the deletion of around 400 amino-acid residues of the D7L homologue and thus to the loss of the (PRANC) domain. It has been observed that the zoonotic CPXV, which has the broadest host range among poxviruses, contains the highest number of ANK/F-box encoding genes compared to all other mammalian poxviruses34,37 while human-adapted Molluscipox virus lacks these genes. ANK/F-box proteins thus confirm to be promising candidates for explaining differences in the host range of poxviruses34,37.

Conclusion

The study of the evolutionary dynamics of MPXV has been largely based on the characterization of APOBEC mutations, providing important insights into the virus’ mechanisms of adaptation to humans. In this study, we set up a methodology whose key feature is its ability to not only detect APOBEC style, but also to specifically classify APOBEC-signature mutations, defined as those mutations falling entirely within a single codon. This functionality enables high-resolution mapping of the functional impact of APOBEC mutations.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first pipeline in the literature that implements a dual-level filtering approach for APOBEC mutations, combining the selection of specific APOBEC-style mutations with a codon-specific verification step to identify mutations of potentially functional and evolutionary relevance.

It is worth emphasizing that, to improve or understanding of MPXV evolutionary strategies enhancing adaptation to the human species, it is vital to explore further genomic regions. The results, obtained on the F8L and G9R factors, contribute to widen the knowledge on the dynamics that led to the emergence of lineages A and B of MPXV clade IIb.

Finally, the study of gene disruptions and protein length polymorphisms represents an additional source for understanding the MPXV evolutionary strategies. The identified D7L protein truncation may represent a less explored evolutionary pattern. Our study confirm the importance of continuing genomic surveillance, even outside usual pathways, for anticipating viral behavior, informing public health interventions, and strengthening preparedness for future outbreaks.

Limitations

Given the widespread diffusion of lineage B of clade IIb outside endemic areas, there is a disproportionate availability of genomes of B sub-lineages (> 11.000 genomes uploaded on GISAID consulted on 14th March 2025) and a limited amount of A lineage variants (828 genomes uploaded on GISAID consulted on 14th March 2025) making it difficult to perform comprehensive evolutionary studies and formulate hypotheses.

This study further shows a significant bias in MPXV genomic surveillance, given the data available from the African continent mainly referred to Nigerian isolates that may have limited our understanding of the virus evolutionary dynamics in less explored endemic areas.

Methods

Diagnosis, genome sequencing, and assembly

Methods of diagnostic confirmation for the 11 cases were reported previously18employing two real-time PCR assays: one targeting Orthopoxvirus DNA for viral detection, and a second assay for clade-specific identification13. Written consents for the publication of the scientific results were obtained from all patients. For this study, genomic data were generated for 11 MPXV isolates (Table 1) on Vero cells E6 (CRL-1586, ATCC). After 4 blind passages, viral genomic DNA was extracted from cell culture supernatant after three freeze thaw cycles using QIAamp UltraSens Virus Kit (Qiagen) and viral load was confirmed by real-time PCR38. Libraries were prepared using the Native Barcoding Kit 24 V14 (SQK-NBD114.24; Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), Oxford, UK) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Normalized and pooled libraries were loaded on R10.4.1 flow cells and run for 72 h on MiniION according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Following data acquisition, quality control and adapter trimming were performed on the raw reads. The filtered, high-quality reads for each sample underwent de novo assembly using Flye v.2.9.5 39. Subsequently, reference-based scaffolding was performed using MPXV-M5312_HM12_Rivers (GenBank Accession Number: NC_063383.1) as the reference genome on Lasergene® 17.0 Software (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI, USA) for precise alignment and assembly refinement. Finally, the quality of the assembled genomes was assessed using QUAST v.5.3.0 40 .

Additional genomes

We retrieved the whole-genome sequences labelled as “Complete” from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Virus database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/virus/vssi/#/) as of October 4, 2024. Clade IIb MPXV sequences were subsampled using appropriate filtering criteria. Within clade IIb, representative samples were randomly selected for each lineage.

Quality control and metadata retrieval for the final dataset were conducted using NextClade41 (https://clades.nextstrain.org), resulting in a curated dataset of 267 high-quality clade II MPXV genomes. A complete list of genomes analysed in this study is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Phylogenetic and molecular evolution analysis

The evolutionary trajectory and genomic features of the 11 MPXV samples sequenced were studied by aligning them with all sequences listed in Supplementary Table 1. Multiple sequence alignment (MSA) was conducted with MAFFT v7.525 42 using the –auto option, and the resulting alignment was visualized in Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software v11.0.13 43. To improve accuracy, the alignment was refined with trimAl v1.5 44, applying the gappyout option to exclude non-conserved 5’-3’ UTR (UnTraslated Regions). A maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree was then constructed with IQ-TREE v2.3.6 45which automatically selected the best nucleotide substitution model and performed 10,000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates. Finally, the phylogenetic tree was visualized using iTOL v.7.0 46.

Mutations in putative APOBEC3 motifs and analysis of key protein variations

For the variant analysis, a subset of 120 sequences from lineage and sub-lineage A, as listed in Supplementary Table 1, was selected. To characterize APOBEC-style mutations, we used the MPXV reference genome NC_063383, classified as an NCBI Reference Sequence (RefSeq), since lineage A represents the most recent common ancestor of all MPXV sub-lineage A. Mutations were further annotated using Snipit v1.6 47.

In this study, a bioinformatics pipeline for the identification and analysis of mutations attributed to the activity of the APOBEC3 enzyme family has been developed. Starting from multiple genome alignments against a reference sequence, the pipeline performed SNP calling and selectively filters APOBEC-style mutations (TC → TT, GG → AG, GA → AA), which represent key mutagenic events mediated by APOBEC activity.

The pipeline was implemented in Python, and the results were visualized using the Seaborn and Matplotlib libraries. Statistical analysis of nucleotide frequencies was performed on each lineage independently. Frequencies were calculated from the results of the variant calling pipeline, as described in Results section. We studied the frequency of each detected single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) in that cohort, and for all samples we described the total amount of SNPs as well as APOBEC-predicted mutations.

Furthermore, targeted analyses were conducted on specific genomic regions to investigate mutations in the MPXV DNA Replication Complex (RC), assess potential gene disruptions caused by nucleotide substitutions and identify associated amino acid alterations.

Protein sequence alignment

Protein structure and function were subsequently investigated to study the implications of nucleotide modifications. The reference database for protein search is UniProt17 (https://www.uniprot.org/). Database search is performed with BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool)48as installed at UniProt and sequence alignment is computed with the Align Tool, which aligns protein sequences using the Clustal Omega program (http://www.clustal.org/omega/). Gene designations were given using the Vaccinia virus Copenhagen nomenclature49.

Protein structural modeling

For sequence structural modeling, we adopted the AlFaFold 3 web server50 (developed by Google DeepMind). AlphaFold produces a per-atom model confidence score (the predicted local distance difference test (pLDDT), scaled from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating higher confidence and a more accurate prediction. The server has a sequence length limitation (400 residues). For proteins with a higher sequence length, we adopted models computed by the default method used by the SWISS-MODEL homology modelling pipeline and Structure Assessment - a single model method combining statistical potentials and agreement terms with a distance constraints (DisCo) score. DisCo evaluates consistencies of pairwise CA-CA distances from a model with constraints extracted from homologous structures17,51,52 (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/).

Pairwise structural alignment of models was computed with TM-align installed at the PDB database53 (https://www.rcsb.org/alignment) and model superimposition was visualized with Mol* (/‘molstar/), a modern web-based open-source toolkit for visualization and analysis of molecular data (https://molstar.org/). Figures are done with PyMOL (Schrodinger, LLC. 2010. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 3.1; https://www.pymol.org/).

Data availability

Data availabilityThe whole genome sequences of 11 isolate viruses described here are deposited in GenBank, under the Accession Numbers PV034557-PV034567, and GISAID’s EpiPox databases; under EPI Accession Numbers EPI_ISL_19703774-EPI_ISL_19703785. Code availabilityAll code for the APOBEC analysis has been deposited on GitHub (https://github.com/Physics4MedicineLab/APOBECSeeker).

References

World Health Organization. Global Mpox Trends. https: (2051). https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global/_w_8e9ee070dc1f45c3a0de2051c28804d9/#overviewde28804d9/#overview (2025).

Srivastava, S. et al. Clade ib: a new emerging threat in the Mpox outbreak. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1504154 (2024).

Cevik, M. et al. The 2023–2024 multi-source Mpox outbreaks of clade I MPXV in sub-Saharan africa: alarm bell for Africa and the world. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 146, Preprintathttpsdoiorg101016jijid2024107159 (2024).

Soheili, M. et al. Monkeypox: virology, pathophysiology, clinical characteristics, epidemiology, vaccines, diagnosis, and treatments. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 25, 297–322 (2022).

Fusco, D. et al. A sex and gender perspective for neglected zoonotic diseases. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1031683 (2022).

Happi, C. et al. Urgent need for a non-discriminatory and non-stigmatizing nomenclature for Monkeypox virus. PLoS Biol 20, (2022).

Parker, E. et al. Genomic epidemiology uncovers the timing and origin of the emergence of Mpox in humans. Preprint At. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.06.18.24309104 (2024).

Chowdhury, P. P. D., Haque, M. A., Ahamed, B., Tanbir, M. & Islam, M. R. A brief report on Monkeypox outbreak 2022: historical perspective and disease pathogenesis. Clin. Pathol. 15, 2632010X221131660 (2022).

O’Toole, Á. et al. APOBEC3 deaminase editing in Mpox virus as evidence for sustained human transmission since at least 2016. Sci. (1979). 382, 595–600 (2023).

De Pascali, A. M. et al. Zoonotic orthopoxviruses after smallpox eradication: A shift from crisis response to a one health approach. IJID One Health. 2, 100018 (2024).

Parker, E. et al. Genomic epidemiology uncovers the timing and origin of the emergence of Mpox in humans. MedRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.06.18.24309104 (2024).

Gigante, C. M. et al. Multiple lineages of Monkeypox virus detected in the united states, 2021–2022. Sci. (1979). 378, 560–565 (2022).

Li, Y., Zhao, H., Wilkins, K., Hughes, C. & Damon, I. K. Real-time PCR assays for the specific detection of Monkeypox virus West African and congo basin strain DNA. J. Virol. Methods. 169, 223–227 (2010).

Mauldin, M. R. et al. Exportation of Monkeypox virus from the African continent. J. Infect. Dis. 225, 1367–1376 (2022).

Ndodo, N. et al. Distinct Monkeypox virus lineages co-circulating in humans before 2022. Nat. Med. 29, 2317–2324 (2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Evolutionary trajectory and characteristics of Mpox virus in 2023 based on a large-scale genomic surveillance in shenzhen, China. Nat Commun 15, (2024).

Bateman, A. et al. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D609–D617 (2025).

Gaspari, V. et al. Monkeypox outbreak 2022: clinical and virological features of 30 patients at the sexually transmitted diseases centre of sant’ Orsola hospital, bologna, Northeastern Italy. J Clin. Microbiol 61, (2023).

Palich, R. et al. Viral loads in clinical samples of men with Monkeypox virus infection: a French case series. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23, 74–80 (2023).

Bunge, E. M. et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—A potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 16, (2022).

Loconsole, D. et al. Monkeypox virus infections in Southern italy: is there a risk for community spread?? Int J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19, (2022).

Scarpa, F. et al. Update of the Genetic Variability of Monkeypox Virus Clade IIb Lineage B.1. Microorganisms 12, 1874 (2024).

Otieno, J. R. et al. Global genomic surveillance of Monkeypox virus. Nat. Med. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03370-3 (2024).

Forni, D., Cagliani, R., Pozzoli, U. & Sironi, M. An APOBEC3 Mutational Signature in the Genomes of Human-Infecting Orthopoxviruses. mSphere 8, (2023).

Cambaza, E. M. A review of the molecular Understanding of the Mpox virus (MPXV): genomics, immune evasion, and therapeutic targets. Zoonotic Dis. 5, 3 (2025).

Da Silva, M. & Upton, C. Vaccinia virus G8R protein: A structural ortholog of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). PLoS One 4, (2009).

Kannan, S. R. et al. Mutations in the Monkeypox virus replication complex: potential contributing factors to the 2022 outbreak. J Autoimmun 133, (2022).

Stack, J. et al. Vaccinia virus protein A46R targets multiple Toll-like-interleukin-1 receptor adaptors and contributes to virulence. J. Exp. Med. 201, 1007–1018 (2005).

Honey, K. Viral immunity: new evasion tactic for vaccinia. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5, 358–359 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/nri1617

Li, Y. et al. Monkeypox virus 2022, gene heterogeneity and protein polymorphism. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 8, Preprintathttpsdoiorg101038s41392–Preprintathttpsdoiorg101038s41023 (2023).

Jordan, I. et al. Deleted deletion site in a new vector strain and exceptional genomic stability of Plaque-Purified modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA). Virol. Sin. 35, 212–226 (2020).

McFadden, G. Poxvirus tropism. Nat Rev Microbiol 3, 201–213 Preprint at (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1099

Liang, C., Qian, J. & Liu, L. Biological characteristics, biosafety prevention and control strategies for the 2022 multi-country outbreak of monkeypox. Biosaf Health 4, 376–385 Preprint at (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bsheal.2022.11.001

Bratke, K. A., McLysaght, A. & Rothenburg, S. A survey of host range genes in poxvirus genomes. Infect. Genet. Evol. 14, 406–425 (2013).

Mercer, A. A., Fleming, S. B. & Ueda, N. F-box-like domains are present in most poxvirus Ankyrin repeat proteins. Virus Genes. 31, 127–133 (2005).

Sonnberg, S., Seet, B. T., Pawson, T., Fleming, S. B. & Mercer, A. A. Poxvirus Ankyrin repeat proteins are a unique class of F-box proteins that associate with cellular SCF1 ubiquitin ligase complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 105, 10955–10960 (2008).

Haller, S. L., Peng, C., McFadden, G. & Rothenburg, S. Poxviruses and the evolution of host range and virulence. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 21, 15–40 Preprint at (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2013.10.014

Cheng, W. et al. Development of a SYBR green I real-time PCR for detection and quantitation of orthopoxvirus by using Ectromelia virus. Mol. Cell. Probes. 38, 45–50 (2018).

Kolmogorov, M., Yuan, J., Lin, Y. & Pevzner, P. A. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 540–546 (2019).

Gurevich, A., Saveliev, V., Vyahhi, N. & Tesler, G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29, 1072–1075 (2013).

Aksamentov, I., Roemer, C., Hodcroft, E. & Neher, R. Nextclade: clade assignment, mutation calling and quality control for viral genomes. J. Open. Source Softw. 6, 3773 (2021).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G. & Kumar, S. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027 (2021).

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M. & Gabaldón, T. TrimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25, 1972–1973 (2009).

Nguyen, L. T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating Maximum-Likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2015).

Ciccarelli, F. D. et al. Toward automatic reconstruction of a highly resolved tree of life. Sci. (1979). 311, 1283–1287 (2006).

O’Toole, Á., Aziz, A. & Maloney, D. Publication-ready single nucleotide polymorphism visualization with snipit. Bioinformatics 40, (2024).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10, (2009).

Goebel, S. J. et al. The complete DNA sequence of vaccinia virus. Virology 179, 247–266 (1990).

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with alphafold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024).

Studer, G. et al. QMEANDisCo—distance constraints applied on model quality Estimation. Bioinformatics 36, 1765–1771 (2020).

Waterhouse, A. M. et al. The structure assessment web server: for proteins, complexes and more. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W318–W323 (2024).

Bittrich, S., Segura, J., Duarte, J. M., Burley, S. K. & Rose, Y. RCSB protein data bank: exploring protein 3D similarities via comprehensive structural alignments. Bioinformatics 40, (2024).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the CINECA award under the ISCRA initiative, for the availability of high-performance computing resources and support, which enabled part of the analyses conducted in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by EU funding within the MUR PNRR Extended Partnership initiative on Emerging Infectious Diseases (Project no. PE00000007, INF-ACT) and ELIXIRxNexGenIT (IR0000010) and ELIXIR-IT, the Italian Node for the Research Infrastructure for Life Science Data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sample collection: A.M.D.P., G.R., T.L, G.D., S.Z. and V.S. Sequencing: M.B., M.E.T., F.G,, M.G., A.M.D.P., L.I. and A.S. Genomics and Phylogenetics Analyses: L.I., E.R., M.T.,G.G. and G.C. Proteomic Analyses: R.C. Conceptualization: A.S., L.I., A.M.D.P., M.C., G.C., R.C. and V.S. Methodology: A.M.D.P., L.I, M.B., L.D., M.S.M., A.M., L.G. and C.C. Funding acquisition: V.S., R.C. and A.S. Project administration and leadership: A.S. and V.S. Writing—original draft: A.S., L.I., A.M.D.P., M.B., R.C., E.R. and M.T. Writing—review and editing: V.S., M.C., T.L. and G.C.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

De Pascali, A.M., Ingletto, L., Brandolini, M. et al. Understanding the evolutionary dynamics of Monkeypox virus through less explored pathways. Sci Rep 15, 25849 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11855-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11855-5