Abstract

Recent research has highlighted the significant impact of students’ enjoyment, hope, and effort on their academic English learning within social contexts. However, the complex interconnections among these factors remain unexplored. To address this gap, the present study employs a quantitative approach to investigate the combined influence of specific dimensions of students’ enjoyment and hope on their effort in learning English. A sample of 711 Chinese senior high school students participated in the study by completing questionnaires on enjoyment, hope and effort. The findings, based on structural equation modeling, suggest that FLE-Private (one dimension of foreign language enjoyment) and pathways (one dimension of hope) directly and positively influence students’ effort in foreign language learning. This research offers valuable insights for educators aiming to enhance students’ enjoyment in English learning, foster their strategic approach to language acquisition, and promote their academic success.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The emergence of the “positive psychology turn”1 in applied linguistics has led to a greater attention towards psychological factors such as flow2,3 resilience4,5,6,7 grit8,9,10 and enjoyment11,12,13 which are critical for mitigating psychological distress—a concern amplified by COVID-19’s toll on mental health14. In China’s educational context, where high-stakes exams and teacher-centred pedagogy often dominate, fostering such emotions as buffers against stress and anxiety is of particular import and urgency15 which also aligns with the national curriculum standards that advocate for holistic development and students’ well-being16.

Research on positive emotions in language learning has highlighted enjoyment, a positive affective experience characterized by pleasure and satisfaction11 as being shaped by factors such as teacher attributes (e.g., predictability, friendliness, patience, behaviour, and L2 use) and peer dynamics (e.g., student cooperation)11,17,18,19. Crucially, enjoyment exhibits a negative relationship with factors such as anxiety13,20 while positively correlating with language learning effort21,22,23. Similarly, hope has emerged as an important research focus24 which is especially vital for navigating the lengthy process of language learning and coping with various setbacks and challenges25. For instance, Zhao and Wang26 highlight its capacity to help learners navigate setbacks, while Hejazi and Sadoughi21 and Rand et al.27 further demonstrate its positive associations with both subjective well-being and long-term learning effort. Effort, defined as the time and energy learners invest in language-related activities28 has also been found to correlate with both enjoyment and hope21,29. These findings highlight the complex interplay between psychological factors (e.g., hope and enjoyment) and academic diligence, underscoring the need for holistic approaches to understanding and fostering students’ effort in educational settings.

The Control-Value Theory (CVT)30,31 offers a comprehensive framework for understanding learners’ emotions, both positive and negative, and dissecting their dynamics in L2 educational settings32. According to CVT, achievement emotions—categorized as outcome-focused (e.g., joy, hope, and anxiety) and activity-focused (e.g., enjoyment and frustration)—significantly influence academic accomplishments30. In this light, this study focuses on three CVT-aligned constructs—namely, enjoyment (positive emotion associated with learning activities), hope (positive emotion linked to future outcomes), and effort (observable behaviors in language learning). Specifically, effort, which directly influences academic performance33 is classified as achievement performance within this framework.

While prior research underscores the positive impact of enjoyment and hope on effort, their combined dynamics remain underexplored, especially in the Chinese L2 contexts. To address this gap, the current study examines:

-

RQ1:

What are the levels of students’ enjoyment, hope and effort?

-

RQ2:

How do these three constructs correlate with each other within the language learning process?

-

RQ3:

How do students’ enjoyment and hope predict their effort?

By integrating CVT with empirical evidence, this study advances understanding of how the positive emotional factors collectively influence effort in foreign language learning, offering insights for cultivating resilience and engagement in L2 classrooms.

Literature review

Foreign Language enjoyment

Enjoyment plays a crucial role in language education, as emphasized by numerous scholars12,18,34,35,36. It represents the positive emotions experienced by learners when overcoming challenges, completing tasks, and fulfilling psychological needs during the language learning process18. Foreign language enjoyment (FLE) encompasses both trait emotional experiences and state-specific responses to learning tasks12. While FLE is inherently multidimensional, its conceptualization has evolved through distinct structural frameworks. Dewaele and MacIntyre18 proposed a foundational two-dimensional model, distinguishing between FLE-Social (enjoyment derived from supportive teacher-peer interactions and classroom atmospheres) and FLE-Private (enjoyment rooted in individuals’ accomplishment in language learning). Jin and Zhang12 later expanded this framework by identifying a three-factor structure, which includes enjoyment from teacher support, peer support, and the intrinsic appeal of language learning. However, the original two-dimensional model remains widely adopted due to its cross-cultural validity, as evidenced in studies across diverse contexts such as China13 and Belgium34. For this study, we prioritize Dewaele and MacIntyre’s18 two-dimensional structure to align with its established applicability and theoretical clarity in examining the interplay between emotional support and personal achievement. Furthermore, research in educational psychology has also established a positive correlation between enjoyment and hope27,37. Additionally, studies have indicated that L2 learners who experience higher levels of enjoyment demonstrate increased effort in their language learning endeavors21,22,26,38.

English learning hope

The current literature on hope in the field of second language education is relatively sparse, yet hope is recognized as playing a crucial role in language learning, particularly when learners encounter various obstacles and challenges39,40. According to Snyder et al.41 hope is defined as a mental state characterized by the belief in one’s ability to successfully achieve goals through determined action and strategic planning. This positive motivational state consists of three key components: goal-directed thinking, agency, and pathways. Goal-directed thinking involves the capacity to establish clear and attainable goals, while agency pertains to the belief in one’s capability to accomplish those goals. Pathways, as defined by Oxford’s42 taxonomy, relate to the capacity to identify and pursue multiple routes to achieve one’s goals.

Research has shown that hope can positively influence various aspects of students’ lives, such as overall life satisfaction, personal adjustment, GPA, and self-efficacy beliefs43 and has also been associated with improved academic performance44. Previous research has consistently identified a moderate45,46 to strong47 positive correlation between hope and effort in language learning, with a predominant focus on high school29,48 and undergraduate students49. Moreover, it is noteworthy that various dimensions of enjoyment have been identified as positively influencing different aspects of hope, including agency and pathways (metacognitive strategies)50,51,52.

English learning effort

Effort, as defined by Carbonaro53 refers to the time and energy students dedicate to meeting formal academic requirements. It is widely recognized that effort plays a crucial role in academic success54,55. While effort is often operationalized through quantitative metrics, frameworks such as Carbonaro’s53 intellectual effort and Katsantonis and McLellan’s56 regulation of effort highlight qualitative distinctions in how effort is allocated. Nevertheless, this study emphasizes quantitative effort—measurable investments of time and energy—to align with existing applied linguistics research54,57 and ensure comparability across contexts.

In language learning, effort is closely associated with attention, involving the allocation of cognitive resources toward specific objectives58. It has been assessed through two dimensions: actual effort57 reflecting the tangible actions and behaviours students invest in their language learning process, both inside and outside of the classroom, in order to effectively acquire the language30 and intended effort59,60,61 which captures learners’ aspirations to become proficient L2 users28. Psychological factors further shape effort, exhibiting negative correlations with stressors like anxiety35,62,63 and positive links to well-being factors such as enjoyment and hope21,22,26,29,46,64.

The Control-Value Theory30 provides a foundational framework for understanding how emotions like enjoyment and hope influence academic outcomes32 through their interplay with control and value appraisals. Empirical studies in applied linguistics have largely validated this framework, demonstrating that enjoyment and hope correlate with increased effort21,29 and, subsequently, improved language proficiency22,26. However, despite these findings, there remains limited exploration into the complex relationships between foreign language enjoyment, English learning hope, and English learning effort. Critically, most CVT-informed research in language learning tends to focus on the connections between positive emotional constructs (e.g., foreign language enjoyment) and their negative counterparts (e.g., anxiety), rather than delving into the multifaceted interrelations among these constructs. Drawing from empirical evidence21,45 s classified as achiethis study posits that enjoyment and hope collectively influence students’ efforts in the context of English learning.

Methods

Participants

A total of 736 senior high school students from three cities in Northeast China were invited to respond to questions regarding their experiences of enjoyment, hope, and effort in learning English. Prior to participation, participants and their parents received comprehensive information about the research objectives, with assurances of anonymity and confidentiality. A rigorous screening process eliminated the invalid responses and resulted in a valid sample of 711 students. Among them, 342 students (48.1%) were male and 369 (51.9%) were female. The distribution across different grade levels was as follows: 266 students from grade 1 (37.41%), 219 from grade 2 (30.80%), and 226 from grade 3 (31.79%).

Research instrument

The current study employed a questionnaire as the tool for gathering quantitative data. The questionnaire began with inquiries regarding the respondents’ personal details, such as gender and grade. The following sections consisted of three 5-point Likert scales revolving on enjoyment, hope, and learning effort. All items on these scales were rated from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”), and were presented in Chinese. To ensure clear comprehension by participants, the English versions of the scales were translated into Chinese. The translation process involved an initial translation by the first author, followed by review and refinement by a Chinese-English bilingual speaker, with any discrepancies resolved through discussion.

Foreign language enjoyment

The 21-item scale by Dewaele and MacIntyre18 was used to measure students’ foreign language enjoyment. We validated the scale and found a two-dimensional structure, namely FLE-Private and FLE-Social. FLE-Private examined individual learners’ enjoyment (n = 7, α = 0.880; e.g., Item 03: I don’t get bored). FLE-Social detected enjoyment arising from teachers’ support and a supportive atmosphere (n = 3, α = 0.845; e.g., Item 17: The teacher is supportive). In this study, this scale was found to have good reliability (α = 0.790). According to the benchmarks, the two-dimensional confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model displayed a satisfactory model fit after removing 11 items with all factor loadings more than 0.5 (χ2/df = 2.816, GFI = 0.951, AGFI = 0.918, CFI = 0.962, TLI = 0.948, RMSEA = 0.072, and RMR = 0.043). Moreover, the average variance extracted (AVE) values were higher than 0.4, and the composite reliability (CR) values were higher than 0.7, indicating good convergent validity of the model65. Furthermore, the square root value of the AVE for each subscale was higher than its corresponding correlation coefficient (r), indicating good discriminant validity among the constructs (see Table 1).

English learning hope

The current study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of the English Learning Hope Scale (ELHS), which was adapted from the Trait Hope Scale (TTHS) developed by Snyder et al.41 with items rephrased to reflect L2-specific goals and challenges. The scale validation resulted in a one-factor structure (α = 0.867) after removing four items, specifically pathways (developing ways to achieve goals, n = 4; α = 0.824; e.g., Item 22: I can think of many ways to overcome challenges in English learning.). Its model fit met the theoretical criteria with all factor loadings more than 0.566 (χ2/df = 1.873, GFI = 0.995, AGFI = 0.974, CFI = 0.996, TLI = 0.989, RMSEA = 0.050, and RMR = 0.019). The CR and AVE were 0.81 and 0.52, supporting the good convergent validity of the model65. Owing to the unidimensionality of the construct, the discriminant validity was not examined (see Table 2).

English learning effort

The English Learning Effort Scale (ELES) was adapted from Gao’s57 work and assessed learners’ actual effort through 11 items describing specific, observable behaviors in their English learning. Five negative descriptions were reversed during data processing. After validation testing by CFA, eight items were deleted, resulting in a final three-item construct of effort with high reliability (α = 0.752). The modified CFA model produced a saturated model with all factor loadings exceeding 0.5. The CR and AVE were 0.75 and 0.51, supporting adequate convergent validity of the model65. Discriminant validity was not assessed due to the unidimensional structure of the construct (see Table 3).

Data collection and data analysis

The questionnaire was distributed in June 2023 via the Wenjuanxing questionnaire system (https://www.wjx.cn/) (accessed on 1 June 2023). Participants were informed of the research objectives in advance and encouraged to provide candid responses based on their genuine learning experiences. The data analysis processing comprised of three steps. In the first step, univariate normality tests were conducted to ensure the normal distribution of the collected data, with skewness and kurtosis values less than |2.0| as the criterion for normality, in line with recommended guidelines67. Second, descriptive and correlational statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 to have an overall view of the levels of the targeted variables and examine the correlations between our targeted variables. In the last step, we conducted multiple linear regressions to explore the role of FLE-Social, FLE-Private, and hope (pathways) on effort.

Results

General patterns of students’ foreign Language enjoyment, hope and effort

The results of the descriptive analysis in Table 4 indicate that the participants experienced moderate levels of enjoyment and hope (3.74 and 3.27 out of 5, respectively) and moderate to low levels of effort (2.97 out of 5).

The predictive effect of enjoyment and hope on effort

Table 5 shows that the correlations among the three variables are significant except for the correlation efficient between FLE-So and Hope. Given the non-significant correlation between FLE-So and Hope, the practical association between these two constructs should be interpreted as weak and limited.

The results of the regression method “enter” indicated that except for “FLE-Social”, the other two independent variables have a significant positive predictive role in effort (as shown in Table 6). The R-squared value of 0.352 suggests that the combination of FLE-Private, FLE-Social, and Hope can account for 35.2% of the variance in students’ effort scores. Table 3 displays that the standardized regression coefficient (Beta) for FLE-Private (Beta = 0.537) is higher than that for hope (Beta = 0.117), indicating that FLE-private has a stronger explanatory power for the variance in student effort than hope. Additionally, both the standardized coefficients for FLE-private and hope in relation to student empathy are positive, suggesting that the higher FLE-private and hope students have, the more effort they exert. The standardized regression equation for this analysis is expressed as:

Discussion

According to Dewaele and Alfawzan’s36 assessment of FLE levels, this study utilizes a 5-point Likert scale, where 3–4 points indicate a moderate level. Table 1 presents the average FLE score of high school students in learning English, which is 3.74, indicating a reasonable level of FLE. The overall findings of the study revealed that students’ enjoyment levels were average, consistent with the previous research by Dewaele and Li68. Additionally, following Snyder’s69 classification of hope levels, a score range of 0.6–1.25 points is considered moderate. Moreover, the reported level of effort also indicates that Chinese senior high school students generally allocate a moderate to low level of actual effort towards English learning, even when positive emotions are present. On the whole, these quantitative results align with the research conducted by Schweder and Raufelder70.

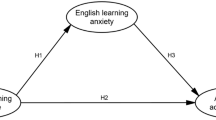

This study extends Control-Value Theory (CVT) by conducting in-depth investigation into the specific impacts of enjoyment and hope on effort in foreign language learning using Amos path analysis. It is revealed that overall enjoyment positively predicts effort, particularly regarding relation to FLE-Private. Previous research has consistently shown that when students derive enjoyment from their educational experiences, they demonstrate a greater willingness to exert effort, actively engage in classroom activities, and persevere through challenges70. Furthermore, research has indicated that enjoyment is a positive predictor of effort in various contexts, including foreign language learning21,22,26,71. For example, Hejazi and Sadoughi’s21 study demonstrates that enjoyment contributes to sustained effort and interest in challenging second language learning processes. However, the impact of FLE-Social on effort was found to be insignificant. Subsequent confirmatory factor analysis revealed that the remaining items in the FLE-Social section specifically related to enjoyment derived from teacher support. According to Pekrun’s Control-Value Theory, when individuals value an achievement-related activity and perceive it as controllable, they are hypothesized to experience feelings of pleasure. Accordingly, the internal perception of value can consistently serve as a motivator for students to derive enjoyment. On the other hand, teacher support offers external assistance and helps students recognize external values in learning. However, due to its lack of constancy and enduring presence, teacher support leads to inherently unstable enjoyment, with limited impact on student effort.

Furthermore, the findings suggest that hope, operationalized specifically as pathways, is a significant positive predictor of effort in language learning. Research has shown that hope directly and positively influences effort46,69,72. According to Snyder69 hope acts as a motivator for increased determination and effort, as individuals with hope tend to view obstacles as challenges to be overcome rather than insurmountable barriers. Similarly, MacIntyre and Gregersen72 demonstrate that hope, defined as the belief in one’s ability to overcome challenges and succeed, is linked to higher levels of effort in the face of difficulties. Additionally, Jiang and Liu46 also found that students with higher level of hope tended to be more willing to plan their study and put more efforts in English learning. In this study, hope is conceptualized as pathways, highlighting the importance of learning strategies, particularly metacognitive ones such as making plans. Recent research has shown that students’ enjoyment and use of metacognitive strategies significantly influence their effort levels70. Moreover, students with proactive attitudes towards problem-solving are more likely to set meaningful goals, remain optimistic about future outcomes, and dedicate effort to achieving those goals73.

Conclusion and implications

The present study has examined the complex interactions between enjoyment, hope, and effort. The findings indicated that students demonstrated moderate levels of enjoyment and hope (3.74 and 3.27 out of 5, respectively) and moderate to low levels of effort (2.97 out of 5). Multiple linear regressions analysis revealed that both FLE-Private and hope were significant and positive predictors of students’ effort. In other words, higher levels of FLE-Private and pathways were associated with increased effort from students.

The findings of this study make a valuable contribution to the existing body of theoretical knowledge. Firstly, it advances research on emotions in foreign language learning by exploring the correlation between two positive academic emotions (enjoyment and hope) and effort based on CVT theory. Secondly, it deepens the understanding of hope in foreign language education and reveals that only the component of pathways was retained in the final dimension of hope, highlighting the need for further investigation in future research. Lastly, this study emphasizes actual effort, as opposed to intended effort, which has been the focus of most previous studies59,60,61.

However, cultural factors can influence intended effort and introduce a certain degree of unpredictability61. This study, therefore, aims to investigate the correlation between positive psychological factors and actual effort, with the goal of providing practical insights for educational practice. In the context of English teaching, educators should utilize students’ past achievements and interests to foster a sense of accomplishment and enjoyment, where highlighting the tangible benefits of English proficiency and linking language learning to students’ future aspirations is essential. In addition, encouraging self-directed learning empowers students to independently explore effective learning strategies, promoting autonomy and self-efficacy.

Furthermore, it is essential for teachers to recognize and reward students’ efforts in order to foster a positive learning environment. Acknowledging their progress not only boosts self-confidence but also motivates further investment in their language learning process. Additionally, cultivating a growth mindset by instilling belief in students’ abilities and providing constructive feedback also helps foster resilience in the face of challenges.

To enhance students’ enjoyment of learning English, teachers should incorporate diverse instructional strategies. Specifically, interactive and communicative language activities, real-world applications, and collaborative learning opportunities not only make learning engaging but also cultivate a sense of belonging and camaraderie among students.

Moreover, academic support services should address both language proficiency and psychological aspects of learning. Guidance counsellors can support students in setting realistic and motivating language learning objectives, while emphasizing the importance of perseverance and resilience. Incorporating activities focused on pathway development, such as reflective exercises and progress tracking, can enhance students’ awareness of their learning trajectory and strengthen their commitment to achieving their language learning goals.

Despite the attempt of the current study to unravel the intricate relationships between students’ enjoyment, hope and effort, several limitations should be noted. Firstly, regarding the dataset, this study focused exclusively on one aspect of hope–specifically, pathways. This limitation is partly due to the cultural context in which the data was gathered. Future research is encouraged to gather data from a broader range of cultural contexts to enhance the comprehensiveness of the dataset. Secondly, it is recommended that future studies conduct qualitative follow-up research to track the participants’ developmental changes in enjoyment, hope and effort over a continuous period, which would offer a more dynamic understanding of how these factors evolve over time.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author because the data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

MacIntyre, P. D., Gregersen, T. & Mercer, S. Positive Psychology in SLA (Multilingual Matters, 2016).

Liu, H. & Song, X. Exploring flow in young Chinese EFL learners’ online english learning activities. System 96, 102425 (2021).

MacIntyre, P. D., Ross, J. & Sparling, H. Flow experiences and willingness to communicate: Connecting Scottish Gaelic Language and traditional music. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 38, 536–545 (2019).

Namaziandost, E. & Heydarnejad, T. Mapping the association between productive immunity, emotion regulation, resilience, and autonomy in higher education. Asian-Pac J. Second Foreign Lang. Educ. 8, 33 (2023).

Namaziandost, E., Rezai, A., Heydarnejad, T. & Kruk, M. Emotion and cognition are two wings of the same bird: Insights into academic emotion regulation, critical thinking, self-efficacy beliefs, academic resilience, and academic engagement in Iranian EFL context. Think. Ski Creat. 50, 101409 (2023).

Liu, H. & Chu, W. Exploring EFL teacher resilience in the Chinese context. System 105, 102752 (2022).

Proietti Ergün, A. L. & Dewaele, J.-M. Do well-being and resilience predict the foreign Language teaching enjoyment of teachers of italian? System 99, 102506 (2021).

Teimouri, Y., Plonsky, L. & Tabandeh, F. L2 grit: Passion and perseverance for second-language learning. Lang. Teach. Res. 26, 893–918 (2022).

Liu, H., Li, X. & Yan, Y. Demystifying the predictive role of students’ perceived foreign Language teacher support in foreign Language anxiety: The mediation of L2 grit. J Multiling. Multicult Dev. 46, 1095–1108 (2025).

Liu, H., Li, X. & Guo, G. Students’ L2 grit, foreign Language anxiety and Language learning achievement: A latent profile and mediation analysis. Int Rev. Appl. Linguist Lang. Teach (2025).

Dewaele, J. M. & MacIntyre, P. D. The two faces of janus? Anxiety and enjoyment in the foreign Language classroom. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 4, 237–274 (2014).

Jin, Y. & Zhang, L. J. The dimensions of foreign Language classroom enjoyment and their effect on foreign Language achievement. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 24, 948–962 (2018).

Jiang, Y. & Dewaele, J. M. How unique is the foreign Language classroom enjoyment and anxiety of Chinese EFL learners? System 82, 13–25 (2019).

Yi, J. et al. The effect of primary and middle school teachers’ problematic internet use and fear of COVID-19 on psychological need thwarting of online teaching and psychological distress. Healthcare 9, 1199 (2021).

Cao, C. H. et al. Psychometric evaluation of the depression, anxiety, and stress scale-21 (DASS-21) among Chinese primary and middle school teachers. BMC Psychol. 11, 209 (2023).

Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. 普通高中英语课程标准 (2017年版 2020年修订) [English Curriculum Standards for Ordinary Senior High Schools (2017 Edition, 2020 Revision)] (People’s Education, 2020).

Chen, I. H., Gamble, J. H. & Lin, C. Y. Peer victimization’s impact on adolescent school belonging, truancy, and life satisfaction: A cross-cohort international comparison. Curr. Psychol. 42, 1402–1419 (2023).

Dewaele, J. M. & MacIntyre, P. D. Foreign Language enjoyment and foreign Language classroom anxiety: The right and left feet of the Language learner. in Positive Psychology in SLA (eds MacIntyre, P. D., Gregersen, T. & Mercer, S.) 215–236 (Multilingual Matters, Bristol, 2016).

Dewaele, J. M. & MacIntyre, P. D. The predictive power of multicultural personality traits, learner and teacher variables on foreign Language enjoyment and anxiety. in Evidence-Based Second Language Pedagogy (eds Sato, M. & Loewen, S.) 263–286 (Routledge, 2019).

Saito, K., Dewaele, J., Abe, M. & In’nami, Y. Motivation, emotion, learning experience, and second Language comprehensibility development in classroom settings: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Lang. Learn. 68, 709–743 (2018).

Hejazi, S. Y. & Sadoughi, M. How does teacher support contribute to learners’ grit? The role of learning enjoyment. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 17, 593–606 (2023).

Khajavy, G. H. & Aghaee, E. The contribution of grit, emotions and personal bests to foreign Language learning. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 45, 2300–2314 (2024).

Liu, H., Li, X. & Wang, X. Students’ mindsets, burnout, anxiety and classroom engagement in Language learning: A latent profile analysis. Innov Lang. Learn. Teach. (2025).

Bright, F. A. S., Kayes, N. M., McCann, C. M. & McPherson, K. M. Hope in people with aphasia. Aphasiology 27, 41–58 (2013).

Gass, S. M., Behney, J. & Plonsky, L. Second Language Acquisition: An Introductory Course (Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2020).

Zhao, X. & Wang, D. Grit, emotions, and their effects on ethnic minority students’ english Language learning achievements: A structural equation modelling analysis. System 113, 102979 (2023).

Rand, K. L., Shanahan, M. L., Fischer, I. C. & Fortney, S. K. Hope and optimism as predictors of academic performance and subjective well-being in college students. Learn. Individ Differ. 81, 101906 (2020).

Dörnyei, Z. The Psychology of the Language Learner: Individual Differences in Second Language Acquisition (Routledge, 2010).

Idan, O., Margalit, M. Socioemotional self-perceptions family climate, and hopeful thinking among students with learning disabilities and typically achieving students from the same classes. J. Learn. Disabil. 47, 136–152 (2014).

Pekrun, R. The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 18, 315–341 (2006).

Pekrun, R. Control-value theory: A social-cognitive approach to achievement emotions. in Big Theories Revisited 2: A Volume of Research on Sociocultural Influences on Motivation and Learning (eds Liem, G. A. D. & McInerney, D. M.) 162–190 (Information Age Publishing., Charlotte, NC, 2018).

Shao, K., Stockinger, K., Marsh, H. W. & Pekrun, R. Applying control-value theory for examining multiple emotions in L2 classrooms: Validating the achievement emotions Questionnaire – Second Language learning. Lang Teach. Res. 13621688221144497 (2023).

Finn, A. S., Lee, T., Kraus, A. & Hudson Kam, C. L. When it hurts (and Helps) to try: The role of effort in Language learning. PLoS ONE. 9, e101806 (2014).

De Smet, A., Mettewie, L., Galand, B., Hiligsmann, P. & Van Mensel, L. Classroom anxiety and enjoyment in CLIL and non-CLIL: Does the target Language matter? Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 8, 47–71 (2018).

Wang, Y. & Ren, W. L2 grit and pragmatic comprehension among Chinese postgraduate learners: Enjoyment and anxiety as mediators. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 34, 224–241 (2024).

Dewaele, J. M. & Alfawzan, M. Does the effect of enjoyment outweigh that of anxiety in foreign Language performance? Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 8, 21–45 (2018).

Hutz, C. S., Midgett, A., Pacico, J. C., Bastianello, M. R. & Zanon, C. The relationship of hope, optimism, self-esteem, subjective Well-Being, and personality in Brazilians and Americans. Psychology 05, 514–522 (2014).

Liu, H., Shen, Z., Shen, Y. & Xia, M. Exploring the predictive role of students’ perceived teacher support on empathy in english-as‐a‐foreign‐language learning. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2025, 2577602 (2025).

Zhao, Y. On the relationship between second Language learners’ grit, hope, and foreign Language enjoyment. Heliyon 9, e13887 (2023).

Guo, G. & Liu, H. Demystifying the relationship between students’ L2 grit and L2 hope. J. Psychol. Perspect. 7, 99–110 (2025).

Snyder, C. R. et al. The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 60, 570–585 (1991).

Oxford, R. L. Language learning strategies and beyond: A look at strategies in the context of styles. in Shifting the instructional focus to the learner (ed. S. S. Magnan) 35–55 Northeast Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages, (Middlebury, VT, 1990).

Gilman, R., Dooley, J. & Florell, D. Relative levels of hope and their relationship with academic and psychological indicators among adolescents. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 25, 166–178 (2006).

Snyder, C. R. et al. Hope and academic success in college. J. Educ. Psychol. 94, 820–826 (2002).

Derakhshan, A. & Yin, H. Do positive emotions prompt students to be more active? Unraveling the role of hope, pride, and enjoyment in predicting Chinese and Iranian EFL students’ academic engagement. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 1–19 (2024).

Jiang, Y. & Liu, H. The relationship between senior high school students’ english learning hope and english learning effort. Eur. J. Engl. Lang. Stud. 4–2024, 165–177 (2024).

Oxford, R. L. Teaching and Researching Language Learning Strategies: Self-Regulation in Context. (Routledge, Abingdon-on-Thames, 2016).

Liu, H., Wang, Y. & Wang, H. Exploring the mediating roles of motivation and boredom in basic psychological needs and behavioural engagement in english learning: A self-determination theory perspective. BMC Psychol. 13, 179 (2025).

Jiang, Y. & Peng, J. E. Exploring the relationships between learners’ engagement, autonomy, and academic performance in an english Language MOOC. Comput Assist. Lang. Learn. 38, 71–96 (2023).

Mameli, C., Grazia, V. & Molinari, L. The emotional faces of student agency. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 77, 101352 (2021).

Obergriesser, S. & Stoeger, H. Students’ emotions of enjoyment and boredom and their use of cognitive learning strategies – How do they affect one another? Learn. Instr. 66, 101285 (2020).

Liu, H., Elahi Shirvan, M. & Taherian, T. Revisiting the relationship between global and specific levels of foreign Language boredom and Language engagement: A moderated mediation model of academic buoyancy and emotional engagement. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 15, 13–39 (2024).

Carbonaro, W. Tracking, students’ effort, and academic achievement. Sociol. Educ. 78, 27–49 (2005).

Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Roberts, B. W., Schnyder, I. & Niggli, A. Different forces, same consequence: Conscientiousness and competence beliefs are independent predictors of academic effort and achievement. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 97, 1115–1128 (2009).

Liew, J., Chen, Q. & Hughes, J. N. Child effortful control, teacher–student relationships, and achievement in academically at-risk children: Additive and interactive effects. Early Child. Res. Q. 25, 51–64 (2010).

Katsantonis, I. & McLellan, R. Students’ voices: A qualitative study on contextual, motivational, and Self-Regulatory factors underpinning Language achievement. Educ. Sci. 13, 804 (2023).

Gao, Y., Zhao, Y., Cheng, Y. & Zhou, Y. Relationship between english learning motivation types and Self-Identity changes among Chinese students. TESOL Q. 41, 133–155 (2007).

Cowan, N. Working Memory Capacity (Psychology Press, 2012).

Martinović, A., Burić, I. L. & Motivation The relationship between past attributions, the L2MSS, and intended effort. J. Foreign Lang. 13, 409–426 (2021).

Amrous, N. L2 motivational self and english department students’ intended effort. in English Language Teaching in Moroccan Higher Education (eds Belhiah, H., Zeddari, I., Amrous, N., Bahmad, J. & Bejjit, N.) 95–107 (Springer Singapore, 2020).

Kwok, C. K. & Carson, L. Integrativeness and intended effort in Language learning motivation amongst some young adult learners of Japanese. Lang. Learn. High. Educ. 8, 265–279 (2018).

Putwain, D. W. & Symes, W. Does increased effort compensate for performance debilitating test anxiety? Sch. Psychol. Q. 33, 482–491 (2018).

Hoch, E., Sidi, Y., Ackerman, R., Hoogerheide, V. & Scheiter, K. Comparing mental effort, difficulty, and confidence appraisals in problem-solving: A metacognitive perspective. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 35, 61 (2023).

Levi, U., Einav, M., Ziv, O., Raskind, I. & Margalit, M. Academic expectations and actual achievements: The roles of hope and effort. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 29, 367–386 (2014).

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39 (1981).

Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (Guilford, 2016).

Kunnan, A. J. An introduction to structural equation modelling for Language assessment research. Lang. Test. 15, 295–332 (1998).

Dewaele, J. M. & Li, C. Foreign Language enjoyment and anxiety: Associations with general and Domain-Specific english achievement. Chin. J. Appl. Linguist. 45, 32–48 (2022).

Snyder, C. R. Handbook of Hope (Academic, 2000).

Schweder, S. & Raufelder, D. Adolescents’ enjoyment and effort in class: Influenced by self-directed learning intervals. J. Sch. Psychol. 95, 72–89 (2022).

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C. & Paris, A. H. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 74, 59–109 (2004).

MacIntyre, P. & Gregersen, T. Affect: The role of Language anxiety and other emotions in Language learning. in Psychology for Language Learning (eds Mercer, S., Ryan, S. & Williams, M.) 103–118 (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2012).

Martin, A. J., Yu, K., Ginns, P. & Papworth, B. Young people’s academic buoyancy and adaptability: A cross-cultural comparison of China with North America and the united Kingdom. Educ. Psychol. 37, 930–946 (2017).

Funding

This paper was not supported by any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H. L, Y. J and H. N; Investigation, H. L; Methodology, H. L and H. N; Supervision, H. L; Writing – original draft, H. L, Y. J and H. N; Writing – review & editing, H. L, Y. J and H. N.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were carried out in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Since this study does not involve intervention and it is low risk, ethical review and approval were waived according to the institutional review boards at School of Foreign Language in Soochow University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Each participant was required to sign a written form of informed consent. All participants were informed about the aim of the study and their right to withdraw from the study at any time. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, H., Jiang, Y., Nie, H. et al. Unveiling the effects of enjoyment and hope on students’ English learning effort. Sci Rep 15, 26630 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11904-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11904-z